New Zealand Parliament

New Zealand Parliament Pāremata Aotearoa | |

|---|---|

| 51st New Zealand Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | House of Representatives |

| History | |

| Founded | 24 May 1854 |

| Leadership | |

Elizabeth II since 6 February 1952 | |

Dame Patsy Reddy since 28 September 2016 | |

Leader of the House | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 121 |

| |

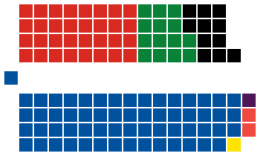

Political groups | Government (63)

Supported by (4)

Opposition (57) |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Parliament House, Wellington, New Zealand | |

| Website | |

| www.parliament.nz/en-NZ | |

The New Zealand Parliament (Māori: Pāremata Aotearoa) is the legislative branch of New Zealand, consisting of the Queen of New Zealand (Queen-in-Parliament) and the New Zealand House of Representatives. Before 1951, there was an upper chamber, the New Zealand Legislative Council. The Parliament was established in 1854 and is one of the oldest continuously functioning parliaments in the world.[1]

The House of Representatives is a democratically elected body whose members are known as Members of Parliament (MPs). It usually consists of 120 MPs, though sometimes more due to overhang seats. 70 MPs are elected directly in electorate seats and the remainder are filled by list MPs based on each party's share of the party vote. Māori were represented in Parliament from 1867, and in 1893 women gained the vote.[1] New Zealand does not allow sentenced prisoners to vote.[2]

The Parliament is closely linked to the executive branch. New Zealand's government comprises a prime minister (leader of the government) and ministers in charge of government departments; per the tenets of responsible government, these ministers are drawn from the governing party or parties in the House of Representatives.

The House of Representatives has met in the Parliament Buildings located in Wellington, the capital city of New Zealand since 1865. Parliament funds the broadcast of its proceedings through Parliament TV, AM Network and Parliament Today.

History

The New Zealand Parliament was created by the British New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 which established a bicameral legislature officially called the "General Assembly", but usually referred to as Parliament. It was based on the Westminster model (that is, the model of the British Parliament) and had a lower house, called the House of Representatives, and an upper house, called the Legislative Council. The members of the House of Representatives were elected under the first-past-the-post (FPP) voting system, while those of the Council were appointed by the Governor. Originally Councillors were appointed for life, but later their terms were fixed at seven years. This change, coupled with responsible government (whereby the Premier advised the Governor on Council appointments) and party politics, meant that by the 20th century, the government usually controlled the Council as well as the House, and the passage of bills through the Council became a formality. In 1951, the Council was abolished altogether, making the New Zealand legislature unicameral.

Under the Constitution Act, legislative power was also conferred on New Zealand's provinces (originally six in number), each of which had its own elected Legislative Council. These provincial legislatures were able to legislate for their provinces on most subjects. However, New Zealand was never a federal dominion like Canada or Australia; Parliament could legislate concurrently with the provinces on any matter, and in the event of a conflict, the law passed by Parliament would prevail. Over a twenty-year period, political power was progressively centralised, and the provinces were abolished altogether in 1876.

Four Māori electorates were created in 1867 during the term of the 4th Parliament.

Originally the New Zealand Parliament remained subordinate to the British Parliament, the supreme legislative authority for the entire British Empire. The New Zealand Parliament received progressively more control over New Zealand affairs through the passage of Imperial (British) laws such as the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, constitutional amendments, and an increasingly hands-off approach by the British government. Finally, in 1947, the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act gave Parliament full power over New Zealand law, and the British New Zealand Constitution Amendment Act 1947 allowed Parliament to regulate its own composition. In 1986 a new Constitution Act was passed, restating the few remaining provisions of the 1852 Act, consolidating the legislation establishing Parliament and officially replacing the name "General Assembly" with "Parliament".

Country quota

One historical speciality of the New Zealand Parliament was the country quota, which gave greater representation to rural politics. From 1889 on (and even earlier in more informal forms), districts were weighted according to their urban/rural split (with any locality of less than 2,000 people considered rural). Those districts which had large rural proportions received a greater number of nominal votes than they actually contained voters – as an example, in 1927, Waipawa, a district without any urban population at all, received an additional 4,153 nominal votes to its actual 14,838 – having the maximum factor of 28% extra representation. The country quota was in effect until it was abolished in 1945 by a mostly urban-elected Labour government, which went back to a one man, one vote system.[3]

Sovereignty

|

|---|

|

|

The New Zealand Parliament is sovereign with no institution able to over-ride its decisions.[4] The ability of Parliament to act is, legally, unimpeded. For example, the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 is a normal piece of legislation, it is not superior law as codified constitutions are in some other countries. The only thing Parliament is limited in its power are on some "entrenched" issues relating to elections. These include the length of its term, deciding on who can vote, how they vote (via secret ballot), how the country should be divided into electorates, and the make up of the Representation Commission which decides on these electorates. These issues require either 75% of all MPs to support the bill or a referendum on the issue. (However, the entrenchment of these provisions is not itself entrenched. Therefore, Parliament can repeal the entrenchment of these issues with a simple majority, then change these issues with a simple majority.)[5]

Monarch

The Queen of New Zealand is one of the components of Parliament—formally called the Queen-in-Parliament. This results from the role of the monarch (or their vice-regal representative, the Governor-General) to sign into law (give Royal Assent) the bills that have been passed by the House of Representatives.

Members of Parliament must express their loyalty to the Queen and defer to her authority, as the Oath of Allegiance must be recited by all new parliamentarians before they may take their seat,[6] and the official opposition is traditionally dubbed as Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition.

Houses

House of Representatives

The House of Representatives was established as a lower house and has been the Parliament's sole chamber since 1951. It is democratically-elected every three years, with eighteen select committees to scrutinise legislation.[7] It is where representatives (called Members of Parliament) assemble to pass laws, scrutinise the government and approve the money it requires.

Upper house

The Parliament does not currently have an upper house; there was an upper house up to 1950, and there have been occasional suggestions to create a new one.[7]

The Legislative Council chamber continues to be used during the State Opening of Parliament, and is where the Governor-General delivers his speech from the throne to the Members of Parliament. This is in keeping with the British tradition in which the monarch is barred from entering the lower house. Similar to the British counterpart, the Black Rod is sent to the House of Representatives to summon the members to the Legislative Council chamber for the Governor-General's speech.

Legislative Council

The Legislative Council was the first legislature of New Zealand, established by the Charter for Erecting the Colony of New Zealand on 16 November 1840,[8] which saw New Zealand established as a Crown colony separate from New South Wales on 1 July 1841.[8] Originally, the Legislative Council consisted of the Governor, Colonial Secretary and Colonial Treasurer (who consisted the Executive Council) and three justices of the peace appointed by the Governor.[9] The Legislative Council had the power to issue Ordinances, statutory instruments.[10]

With the passing of the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, the Legislative Council became the upper house of the General Assembly. The Legislative Council was intended to scrutinise and amend bills passed by the House of Representatives, although it could not initiate legislation or amend money bills. Despite occasional proposals for an elected Council, Members of the Legislative Council (MLCs) were appointed by the Governor, generally on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. At first, MLCs were appointed for life, but a term of seven years was introduced in 1891. It was eventually decided that the Council was having no significant impact on New Zealand's legislative process, and the terms of its members expired on 31 December 1950. At the time of its abolition it had fifty-four members, including its own Speaker.

Senate proposals

In September 1950, the National government of Sidney Holland set up a constitutional reform committee to consider an alternative second chamber, chaired by Ronald Algie. A report produced by the committee in 1952 proposed a nominated Senate, with 32 members, appointed by leaders of the parties in the House of Representatives, according to the parties' strength in that House. Senators would serve for three-year-terms, and be eligible for reappointment.[11] The Senate would have the power to revise, initiate or delay legislation, to hear petitions, and to scrutinise regulations and Orders in Council, but the proposal was rejected by the Prime Minister and by the Labour opposition, which had refused to nominate members to the committee.[12]

The National government of Jim Bolger proposed the establishment of an elected Senate when it came to power in 1990, thereby reinstating a bicameral system, and a Senate Bill was drafted. Under the Bill, the Senate would have 30 members, elected by STV, from six senatorial districts, four in the North Island and two in the South Island. Like the old Legislative Council, it would not have powers to amend or delay money bills.[13] The House of Representatives would continue to be elected by FPP.

The intention was to include a question on a Senate in the second referendum on electoral reform. Voters would be asked, if they did not want a new voting system, whether or not they wanted a Senate.[14] However, following objections from the Labour opposition, which derided it as a red herring,[15] and other supporters of the mixed-member proportional (MMP) representation system,[16] the Senate question was removed by the Select Committee on Electoral Reform.

In 2010, the New Zealand Policy Unit of the Centre for Independent Studies proposed a Senate in the context of the 2011 referendum on MMP. They proposed a proportionally-elected upper house made up 31 seats elected using a proportional list vote by region, with the House of Representatives elected by FPP and consisting of 79 seats.[17]

Passage of legislation

The New Zealand Parliament's model for passing Acts of Parliament is similar (but not identical) to that of other Westminster system governments.

Laws are initially proposed in Parliament as bills. They become Acts after being approved three times by Parliamentary votes and then receiving Royal Assent from the Governor-General. The majority of bills are promulgated by the government of the day (that is, the party or parties that have a majority in Parliament). It is rare for government bills to be defeated, indeed the first to be defeated in the twentieth century was in 1998. It is also possible for individual MPs to promote their own bills, called member's bills; these are usually put forward by opposition parties, or by MPs who wish to deal with a matter that parties do not take positions on.

House of Representatives

Within the House of Representatives, bills must pass through three readings and be considered by both a Select Committee and the Committee of the Whole House.

Royal Assent

If a bill passes its third reading, it is passed by the Clerk of the House of Representatives to the Governor-General, who will (assuming constitutional conventions are followed) grant Royal Assent as a matter of course. Some constitutional lawyers, such as Professor Philip Joseph, believe the Governor-General does retain the power to refuse Royal Assent to bills in exceptional circumstances – specifically if democracy were to be abolished.[18] Others, such as former law professor and Prime Minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Matthew Palmer argue any refusal of Royal Assent would lead to a constitutional crisis.[19]

Refusal of Royal Assent has never occurred under any circumstances in New Zealand. Once Royal Assent has been granted, the bill then becomes law.

Terms of Parliament

Parliament is currently in its 51st term.

See also

- New Zealand Parliament Buildings

- New Zealand general election

- Constitution of New Zealand

- Independence of New Zealand

- Politics of New Zealand

- List of legislatures by country

Notes

- ^ a b "Parliament". teara.govt.nz. Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Prisoners and the Right to Vote

- ^ McKinnon, Malcolm (ed.) (1997). New Zealand Historical Atlas. David Bateman. p. Plate 90.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "New Zealand Sovereignty: 1857, 1907, 1947, or 1987?". New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Electoral Act 1993 s268

- ^ Elizabeth II (24 October 1957), Oaths and Declarations Act 1957, 17, Wellington: Queen's Printer for New Zealand, retrieved 1 January 2010

- ^ a b Wilson 1985, p. 147.

- ^ a b Paul Moon (2010). New Zealand Birth Certificates – 50 of New Zealand's Founding Documents. AUT Media. ISBN 9780958299718.

- ^ "Crown colony era – the Governor-General". 30 August 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "NO. 21. — CHARTER FOR ERECTING THE COLONY OF NEW ZEALAND, AND FOR CREATING AND ESTABLISHING A LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND AN EXECUTIVE COUNCIL, AND FOR GRANTING CERTAIN POWERS AND AUTHORITIES TO THE GOVERNOR FOR THE TIME BEING OF THE SAID COLONY". Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ The New Zealand Legislative Council : A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House, William Keith Jackson, University of Otago Press, page 200

- ^ Memoirs: 1912–1960, Sir John Marshall, Collins, 1984, 159–60

- ^ "Senate Bill : Report of Electoral Law Committee". 7 June 1994.

- ^ "New Zealand Legislates for the 1993 Referendum on its Electoral System". Newsletter of the Proportional Representation Society of Australia (69). March 1993. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011.

- ^ New Zealand Hansard: Tuesday, December 15, 1992 ELECTORAL REFORM BILL : Introduction

- ^ Submission: Electoral Reform Bill (February 1993)

- ^ Luke Malpass and Oliver Marc Hartwich (24 March 2010). "Superseding MMP: Real Electoral Reform for New Zealand" (PDF). Centre for Independent Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Philip Joseph (2002). Constitutional and Administrative Law in New Zealand (2nd ed.). Brookers. ISBN 978-0-86472-399-4.

- ^ Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Matthew Palmer (2004). Bridled Power: New Zealand's Constitution and Government (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558463-5.

References

- McRobie, Alan (1989). Electoral Atlas of New Zealand. Wellington: GP Books. ISBN 0-477-01384-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. OCLC 154283103.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)