Petroglyph

Petroglyphs are images created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions of the technique to refer to such images. Petroglyphs are found world-wide, and are often associated with prehistoric peoples. The word comes from the Greek word petro-, theme of the word "petra" meaning "stone", and glyphein meaning "to carve", and was originally coined in French as pétroglyphe.

The term petroglyph should not be confused with petrograph, which is an image drawn or painted on a rock face. Both types of image belong to the wider and more general category of rock art or parietal art. Petroforms, or patterns and shapes made by many large rocks and boulders over the ground, are also quite different. Inukshuks are also unique, and found only in the Arctic (except for reproductions and imitations built in more southerly latitudes).

A more developed form of petroglyph, normally found in literate cultures, a rock relief or rock-cut relief is a relief sculpture carved on solid or "living rock" such as a cliff, rather than a detached piece of stone. They are a category of rock art, and sometimes found in conjunction with rock-cut architecture.[1] However, they tend to be omitted in most works on rock art, which concentrate on engravings and paintings by prehistoric peoples. A few such works exploit the natural contours of the rock and use them to define an image, but they do not amount to man-made reliefs. Rock reliefs have been made in many cultures, and were especially important in the art of the Ancient Near East.[2] Rock reliefs are generally fairly large, as they need to be to make an impact in the open air. Most have figures that are over life-size, and in many the figures are multiples of life-size.

Stylistically they normally relate to other types of sculpture from the culture and period concerned, and except for Hittite and Persian examples they are generally discussed as part of that wider subject.[3] The vertical relief is most common, but reliefs on essentially horizontal surfaces are also found. The term typically excludes relief carvings inside caves, whether natural or themselves man-made, which are especially found in India. Natural rock formations made into statues or other sculpture in the round, most famously at the Great Sphinx of Giza, are also usually excluded. Reliefs on large boulders left in their natural location, like the Hittite İmamkullu relief, are likely to be included, but smaller boulders may be called stelae or carved orthostats.

History

Some petroglyphs are dated to approximately the Neolithic and late Upper Paleolithic boundary, about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, if not earlier (Kamyana Mohyla). Sites in Australia have petroglyphs that are estimated to be as much as 27,000 years old, and in other places could be as old as 40,000 years. Around 7,000 to 9,000 years ago, other precursors of writing systems, such as pictographs and ideograms, began to appear. Petroglyphs were still common though, and some cultures continued using them much longer, even until contact with Western culture was made in the 20th century. Petroglyphs have been found in all parts of the globe except Antarctica with highest concentrations in parts of Africa, Scandinavia, Siberia, southwestern North America and Australia.

Interpretation

There are many theories to explain their purpose, depending on their location, age, and the type of image. Some petroglyphs are thought to be astronomical markers, maps, and other forms of symbolic communication, including a form of "pre-writing". Petroglyph maps may show trails, symbols communicating time and distances traveled, as well as the local terrain in the form of rivers, landforms and other geographic features. A petroglyph that represents a landform or the surrounding terrain is known as a geocontourglyph. They might also have been a by-product of other rituals: sites in India, for example, have been identified as musical instruments or "rock gongs".[4]

Some petroglyph images probably have deep cultural and religious significance for the societies that created them; in many cases this significance remains for their descendants. Many petroglyphs are thought to represent some kind of not-yet-fully understood symbolic or ritual language. Later glyphs from the Nordic Bronze Age in Scandinavia seem to refer to some form of territorial boundary between tribes, in addition to possible religious meanings. It also appears that local or regional dialects from similar or neighboring peoples exist. The Siberian inscriptions almost look like some early form of runes, although there is not thought to be any relationship between them. They are not yet well understood.

Some researchers have noticed the resemblance of different styles of petroglyphs across different continents; while it is expected that all people would be inspired by their surroundings, it is harder to explain the common styles. This could be mere coincidence, an indication that certain groups of people migrated widely from some initial common area, or indication of a common origin. In 1853 George Tate read a paper to the Berwick Naturalists' Club, at which a John Collingwood Bruce agreed that the carvings had "... a common origin, and indicate a symbolic meaning, representing some popular thought."[5] In his cataloguing of Scottish rock art, Ronald Morris summarised 104 different theories on their interpretation.[6]

Other, more controversial, explanations are grounded in Jungian psychology and the views of Mircea Eliade. According to these theories it is possible that the similarity of petroglyphs (and other atavistic or archetypal symbols) from different cultures and continents is a result of the genetically inherited structure of the human brain.

Other theories suggest that petroglyphs were made by shamans in an altered state of consciousness,[7] perhaps induced by the use of natural hallucinogens. Many of the geometric patterns (known as form constants) which recur in petroglyphs and cave paintings have been shown by David Lewis-Williams to be "hard-wired" into the human brain; they frequently occur in visual disturbances and hallucinations brought on by drugs, migraine and other stimuli.

Recent analysis of surveyed and GPS logged petroglyphs around the world has identified commonalities indicating pre-historic (7,000–3,000 B.C.) intense auroras observable across the continents.[8][9] Specific common associated archetypes include: squatting man, caterpillars, ladders, eye mask, kokopelli, spoked wheels, and others.

Present-day links between shamanism and rock art amongst the San people of the Kalahari desert have been studied by the Rock Art Research Institute (RARI) of the University of the Witwatersrand.[10] Though the San people's artworks are predominantly paintings, the beliefs behind them can perhaps be used as a basis for understanding other types of rock art, including petroglyphs. To quote from the RARI website:

Using knowledge of San beliefs, researchers have shown that the art played a fundamental part in the religious lives of its San painters. The art captured things from the San’s world behind the rock-face: the other world inhabited by spirit creatures, to which dancers could travel in animal form, and where people of ecstasy could draw power and bring it back for healing, rain-making and capturing the game.

List of petroglyph sites

Africa

- Bambari, Lengo and Bangassou in the south; Bwale in the west

- Toulou

- Djebel Mela

- Koumbala

- The Niari Valley, 250 km south west of Brazzaville

- Wadi Hammamat in Qift, many carvings and inscriptions dating from before the earliest Egyptian Dynasties to the modern era, including the only painted petroglyph known from the Eastern Desert and drawings of Egyptian reed boats dated to 4000 BCE

- Inscription Rock in South Sinai, a large rock with carvings and writings ranging from Nabatean to Latin, Ancient Greek and Crusder eras located a few miles from the Ain Hudra Oasis. There is also a second rock approximately 1 km from the main rock near the Nabatean tombs of Nawamis with carvings of various animals including Camels, Gazelles and others. The original archaeologists who investigated these in the 1800s have also left their names carved on this rock.

- Giraffe petroglyphs found in the region of Gebel el-Silsila. The rock faces have been used for extensive quarrying of materials for temple building especially during the period specified as the New Kingdom . The Giraffe depictions are located near a stela of the king Amenhotep IV. The images are not dated, but they are probably dated from the Predynastic periods.

- Ogooue River Valley

- Epona

- Elarmekora

- Kongo Boumba

- Lindili

- Kaya Kaya

- The Draa River valley

- Life-size giraffe carvings on Dabous Rock, Air Mountains

- Driekops Eiland near Kimberley[11]

- ǀXam and ǂKhomani heartland in the Karoo, Northern Cape

- Wildebeest Kuil Rock Art Centre near Kimberley, Northern Cape

- Keiskie near Calvinia, Northern Cape

- Nyambwezi Falls in the north-west province.

Asia

Eight sites in Hong Kong:

- Tung Lung Island

- Kau Sai Chau

- Po Toi Island

- Cheung Chau

- Shek Pik on Lantau Island

- Wong Chuk Hang and Big Wave Bay on Hong Kong Island

- Lung Ha Wan in Sai Kung

- Bhimbetka rock shelters, Raisen District, Madhya Pradesh, India.

- Kupgal petroglyphs on Dolerite Dyke, near Bellary, Karnataka, India.

- Edakkal Caves, Wayanad District, Kerala, India.

- Perumukkal, Tindivanam District, Tamil Nadu, India.

- Kollur, Villupuram, Tamil Nadu.

- Unakoti near Kailashahar in North Tripura District, Tripura, India.

- Usgalimal rock engravings, Kushavati river banks,in Goa[13]

- Ladakh, NW Indian Himalaya.[14]

Recently petroglyphs were found from Kollur village in Tamil Nadu. A big dolmen with four petroglyphs that portray men with trident and a wheel with spokes has been found at Kollur near Triukoilur 35 km from Villupuram. The discovery was made by K.T. Gandhirajan. This is the second time that a dolmen with petrographs has been found in Tamil Nadu, India.[15]

During recent years a large number of rock carvings has been identified in different parts of Iran. The vast majority depict the ibex.[16][17]

- Kibbutz Ginosar

- Har Karkom

- Negev

- Awashima shrine (Kitakyūshū city)[18]

- Hikoshima island (Shimonoseki city)[18]

- Miyajima[18]

- Temiya cave (Otaru city)[19]

- Koksu River, in Almaty Province

- Chumysh River basin,

- Tamgaly Tas on the Ili River

- Tamgaly – a World Heritage Site nearly of Almaty

- Several sites in the Tien Shan mountains: Cholpon-Ata, the Talas valley, Saimaluu Tash, and on the rock outcrop called Suleiman's Throne in Osh in the Fergana valley

- Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai, UNESCO World Heritage site, 2011[20][21]

- The Wanshan Rock Carvings Archeological Site near Maolin District, Kaohsiung, were discovered between 1978 and 2002.

- Rock engravings in Sapa, Sa Pa District, Lào Cai Province

- Rock engravings in Namdan, Xín Mần District, Hà Giang Province

-

Rock carving on Cheung Chau Island, Hong Kong. This 3000-year-old rock carving was reported by geologists in 1970

-

Petroglyphs at Cholpon-Ata in Kyrgyzstan

-

Tamgaly petroglyphs in Kazakhstan

-

Petroglyph found in Awashima shrine (Japan)

Europe

-

Engravers from Val Camonica, Italy

-

Rock Carving in Tanum, Sweden

-

Carving "The Shoemaker", Brastad, Sweden

-

Petroglyph in Roque Bentayga, Gran Canaria (Canary Islands).

-

Petroglyph at Dalgarven Mill, Ayrshire, Scotland.

-

Bronze Age petroglyphs depicting weapons, Castriño de Conxo, Santiago de Compostela, Galicia.

-

Labyrinth, Meis, Galicia.

-

Cup-and-ring mark, Louro, Muros, Galicia.

-

Deer and cup-and-ring motifs, Tourón, Ponte Caldelas, Galicia.

- Northumberland,

- County Durham,

- Ilkley Moor, Yorkshire,

- Gardom's Edge, Derbyshire,

- Creswell Crags, Nottingham

-

The sorcerer, Vallée des Merveilles, France

-

The tribe master, Vallée des Merveilles, France

- Rock Drawings in Valcamonica – World Heritage Site, Italy (biggest European site, over 350,000)

- Bagnolo stele, Valcamonica, Italy

- Grotta del Genovese, Sicily, Italy

- Grotta dell'Addaura, Sicily, Italy

-

Leftmost of three central stones, Knockmany Chambered Tomb, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland

-

Central of three central stones, Knockmany Chambered Tomb, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland

-

A stone on the right of the passage, Knockmany Chambered Tomb, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland

-

Sess Kilgreen Chambered Tomb, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland

-

Sess Kilgreen Chambered Tomb, Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland

- Rock carvings at Alta, World Heritage Site (1985)

- Rock carvings in Central Norway

- Rock carvings at Møllerstufossen

- Rock carvings at Tennes

- Museum of Ayrshire Country Life and Costume, North Ayrshire

- Burghead Bull, Burghead

- Townhead, Galloway[22]

- Petroglyph Park near Petrozavodsk-Lake Onega, Russia

- Tomskaya Pisanitsa

- Kanozero Petroglyphs

- Sikachi-Alyan, Khabarovsk Krai

- Tanumshede (Bohuslän); World Heritage Site (1994)

- Himmelstalund (by Norrköping in Östergötland)

- Enköping (Uppland)

- Southwest Skåne (Götaland)

- Alvhem (Västra Götaland)

- Torhamn (Blekinge)

- Nämforsen (Ångermanland)

- Häljesta (Västmanland)

- Slagsta (Södermanland)

- Glösa (Jämtland)

- The King's Grave at Kivik

- Rock carvings at Norrfors, Umeå[24]

- Kagizman, Kars

- Cunni Cave, Erzurum

- Esatli, Ordu

- Gevaruk Valley, Hakkâri

- Hakkari Trisin, Hakkâri

- Latmos, Beşparmak

- Güdül, Ankara

Central and South America and the Caribbean

-

Hands at the Cuevas de las Manos

-

Hunting scene at the Cuevas de las Manos

The oldest reliably dated rock art in the Americas is known as the "Horny Little Man." It is petroglyph depicting a stick figure with an oversized phallus and carved in Lapa do Santo, a cave in central-eastern Brazil and dates from 12,000 to 9,000 years ago.[25]

- Serra da Capivara National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Piauí

- Vale do Catimbau National Park, Pernambuco

- Ingá Stone, Paraíba

- Costao do Santinho, Santa Catarina

- Lagoa Santa (Holy Lake), Minas Gerais

- Ivolandia, Goiás

-

Capivara National Park, Piauí, Brazil

-

Ivolandia, Goiás, Brazil

-

Costao do Santinho, SC, Brazil

-

Modern science and the spectre of ancient man coexist in this thought-provoking image of a petroglyph.[26]

-

Llamas at La Silla[27]

-

El Abra archaeological site, Cundinamarca

-

Petroglyph in the Chiribiquete Natural National Park. (Possible equine)

-

Petroglyph in the Chiribiquete Natural National Park. Aborigine

-

Petroglyph in the Chiribiquete Natural National Park. (Possible mammal).

-

Petroglyphs in the Chiribiquete Natural National Park.

- Cueva de las Maravillas, San Pedro de Macorís

- Las Caritas, near Lake Enriquillo

- Los Tres Ojos, Santo Domingo

- Cumbe Mayo, Cajamarca

- Petroglyphs of Pusharo, Manú National Park, Madre de Dios region

- Petroglyphs of Quiaca, Puno Region

- Petroglyphs of Jinkiori, Cusco Region

- La Piedra Escrita (The Written Rock), Jayuya

- Caguana Indian Park, Utuado

- Tibes Indian Park, Ponce

- La Cueva del Indio (Indians Cave), Arecibo

- Carib Petroglyphs, Wingfield Manor Estate, Saint Kitts

North America

-

Petroglyphs on a Bishop Tuff tableland, eastern California

-

Southern Utah

-

Southern Utah

-

Animal print carvings outside of Barnesville, Ohio

-

Upside-down man in Western Colorado

-

Web-like petroglyph on the White Tank Mountain Regional Park Waterfall Trail, Arizona

-

Chipping petroglyph on the White Tank Mountain Regional Park Waterfall Trail, Arizona

-

Sample of petroglyphs at Painted Rock near Gila Bend, Arizona off Interstate 8.

- Kejimkujik National Park, Nova Scotia

- Petroglyph Provincial Park, Nanaimo, British Columbia[28]

- Petroglyphs Provincial Park, north of Peterborough, Ontario

- Agnes Lake, Quetico Provincial Park, Ontario

- Sproat Lake Provincial Park, near Port Alberni, British Columbia

- Stuart Lake, British Columbia

- St. Victor Provincial Park, Saskatchewan

- Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, east of Milk River, Alberta

- Gabriola Island, British Columbia [29]

- Boca de Potrerillos, Mina, Nuevo León

- Chiquihuitillos, Mina, Nuevo León

- Cuenca del Río Victoria, near Xichú, Guanajuato

- Coahuiltecan Cueva Ahumada, Nuevo León

- La Proveedora, Caborca, Sonora

- Samalayuca, Juarez, Chihuahua

- Arches National Park, Utah

- Barnesville Petroglyph, Ohio

- California Petroglyphs & Pictographs[30]

- Capitol Reef National Park, Utah

- Columbia Hills State Park, Washington[31]

- Corn Springs, Colorado Desert, California

- Coso Rock Art District, Coso Range, northern Mojave Desert, California[32]

- Death Valley National Park, California

- Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado and Utah

- Dighton Rock, Massachusetts

- Dominguez Canyon Wilderness, Colorado

- Grimes Point, Nevada[33]

- Jeffers Petroglyphs, Minnesota

- Judaculla Rock, North Carolina

- Kanopolis State Park, Kansas

- Lava Beds National Monument, Tule Lake, California

- Legend Rock Petroglyph Site, Thermopolis, Wyoming

- Lemonweir Glyphs, Wisconsin

- Leo Petroglyph, Leo, Ohio [34]

- Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

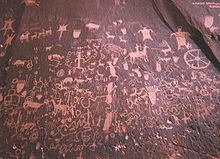

- Newspaper Rock State Historic Monument, Utah

- Olympic National Park, Washington

- Paintlick Mountain, Tazewell, Virginia[35]

- Petit Jean State Park, Arkansas

- Petrified Forest National Park

- Petroglyph National Monument

- Picture Canyon, Flagstaff, Arizona

- Puye Cliff Dwellings, New Mexico

- Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, Nevada

- Rochester Rock Art Panel, Utah

- Ring Mountain, Marin County, California

- Saint John, U.S. Virgin Islands

- Sanilac Petroglyphs Historic State Park, Michigan

- Sedona, Arizona

- Seminole Canyon, Texas

- Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area, Nevada

- South Mountain Park, Arizona

- The Cove Palisades State Park, Oregon

- Three Rivers Petroglyphs, New Mexico [36]

- Valley of Fire State Park, Nevada

- Washington State Park, Washington County, Missouri

- West Virginia glyphs

- White Tank Mountain Regional Park, Waddell, Arizona

- Winnemucca Lake, Nevada

- Writing Rock State Historical Site, North Dakota

Oceania

- Arnhem Land / Kakadu National Park, Northern Australia

- Murujuga, Western Australia – world heritage assessed

- Sydney Rock Engravings, New South Wales

-

Part of a 20-metre-long petroglyph at Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, Australia

-

Mutawintji National Park, Australia

See also

- Geoglyph

- History of communication

- List of Stone Age art

- Megalithic art

- Pecked curvilinear nucleated

- Petrosomatoglyph

- Runestone and image stone

- Water glyphs

Notes

- ^ Harmanşah (2014), 5–6

- ^ Harmanşah (2014), 5–6; Canepa, 53

- ^ for example by Rawson and Sickman & Soper

- ^ Ancient Indians made 'rock music'. BBC News (2004-03-19). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ J. Collingwood Bruce (1868; cited in Beckensall, S., Northumberland's Prehistoric Rock Carvings: A Mystery Explained. Pendulum Publications, Rothbury, Northumberland. 1983:19)

- ^ Morris, Ronald (1979) The Prehistoric Rock Art of Galloway and The Isle of Man, Blandford Press, ISBN 978-0-7137-0974-2.

- ^ [see Lewis-Williams, D. 2002. A Cosmos in Stone: Interpreting Religion and Society through Rock Art. Altamira Press, Walnut Creek, Ca.]

- ^ Peratt, A.L. (2003). "Characteristics for the occurrence of a high-current, Z-pinch aurora as recorded in antiquity". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 31 (6): 1192. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.820956.

- ^ Peratt, Anthony L.; McGovern, John; Qoyawayma, Alfred H.; Van Der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony; Peratt, Mathias G. (2007). "Characteristics for the Occurrence of a High-Current Z-Pinch Aurora as Recorded in Antiquity Part II: Directionality and Source". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 35 (4): 778. doi:10.1109/TPS.2007.902630.

- ^ Rockart.wits.ac.za. Rockart.wits.ac.za. Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Parkington, J. Morris, D. & Rusch, N. 2008. Karoo rock engravings. Clanwilliam: Krakadouw Trust; Morris, D. & Beaumont, P. 2004. Archaeology in the Northern Cape: some key sites. Kimberley: McGregor Museum.

- ^ Khechoyan, Anna. "The Rock Art of the Mt. Aragats System | Anna Khechoyan". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Kamat, Nandkumar. "Petroglyphs on the banks of Kushvati". Prehistoric Goan Shamanism. the Navhind times. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Petroglyphs of Ladakh: The Withering Monuments. tibetheritagefund.org

- ^ Dolmen with petroglyphs found near Villupuram. Beta.thehindu.com (2009-09-19). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Iranrockart, page by researcher M Naserifard

- ^ Middle East rock art archive- Iran Rock Art

- ^ a b c Nobuhiro, Yoshida (1994) The Handbook For Petrograph Fieldwork, Chou Art Publishing, ISBN 4-88639-699-2, p. 57

- ^ Nobuhiro, Yoshida (1994) The Handbook For Petrograph Fieldwork, Chou Art Publishing, ISBN 4-88639-699-2, p. 54

- ^ Petroglyphic Complexes of the Mongolian Altai – UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Whc.unesco.org (2011-06-28). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Fitzhugh, William W. and Kortum, Richard (2012) Rock Art and Archaeology: Investigating Ritual Landscape in the Mongolian Altai. Field Report 2011. The Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- ^ "British Rock Art Blog | A Forum about Prehistoric Rock Art in the British Islands". Rockartuk.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Photos. Celticland.com. (2007-08-13). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ "Umeå, Norrfors". Europreart.net. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Choi, Charles. "Call this ancient rock carving 'little horny man'." Science on MSNBC. 22 Feb 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ "The Ascent of Man". Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ "Llamas at La Silla". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ Petroglyph Provincial Park, Nanaimo, Vancouver Island BC. Britishcolumbia.com. Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Gabriola Island BC

- ^ Petroglyphs.us. Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Keyser, James D. (July 1992). Indian Rock Art of the Columbia Plateau. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97160-5.

- ^ Moore, Donald W. Petroglyph Canyon Tours. Desertusa.com. Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Grimes Point National Recreation Trail, Nevada BLM Archaeological Site. Americantrails.org (2012-01-13). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ Museums & Historic Sites. ohiohistory.org. Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

- ^ "Paint Lick". Craborchardmuseum.com. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Three Rivers Petroglyph Site. Nm.blm.gov (2012-09-13). Retrieved on 2013-02-12.

References

- Harmanşah, Ömür (ed) (2014), Of Rocks and Water: An Archaeology of Place, 2014, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1782976744, 9781782976745

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L. & Soper A., The Art and Architecture of China, Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

Further reading

- Beckensall, Stan and Laurie, Tim, Prehistoric Rock Art of County Durham, Swaledale and Wensleydale, County Durham Books, 1998 ISBN 1-897585-45-4

- Beckensall, Stan, Prehistoric Rock Art in Northumberland, Tempus Publishing, 2001 ISBN 0-7524-1945-5

External links

- Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Bancroft Library's citations to rock art literature.

![Running Priest[citation needed] in Capo di Ponte, Val Camonica, Italy](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Figura_che_corre_-_R_35_-_Parco_di_Naquane_-_Capo_di_Ponte.jpg/118px-Figura_che_corre_-_R_35_-_Parco_di_Naquane_-_Capo_di_Ponte.jpg)

![Modern science and the spectre of ancient man coexist in this thought-provoking image of a petroglyph.[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/The_Ascent_of_Man.jpg/120px-The_Ascent_of_Man.jpg)

![Llamas at La Silla[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Llamas_at_La_Silla.jpg/80px-Llamas_at_La_Silla.jpg)