Pioneer plaque

The Pioneer plaques are a pair of gold-anodized aluminium plaques which were placed on board the 1972 Pioneer 10 and 1973 Pioneer 11 spacecraft, featuring a pictorial message, in case either Pioneer 10 or 11 is intercepted by extraterrestrial life. The plaques show the nude figures of a human male and female along with several symbols that are designed to provide information about the origin of the spacecraft.[1]

The Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft were the first human-built objects to achieve escape velocity from the Solar System. The plaques were attached to the spacecraft's antenna support struts in a position that would shield them from erosion by interstellar dust.

History

The original idea, that the Pioneer spacecraft should carry a message from mankind, was first mentioned by Eric Burgess[2] when he visited the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, during the Mariner 9 mission. He approached Carl Sagan, who had lectured about communication with intelligent extraterrestrials at a conference in Crimea.

Sagan was enthusiastic about the idea of sending a message with the Pioneer spacecraft. NASA agreed to the plan and gave him three weeks to prepare a message. Together with Frank Drake he designed the plaque, and the artwork was prepared by Linda Salzman Sagan, who was Sagan's wife at the time.

Both plaques were manufactured at Precision Engravers, San Carlos, California.

The first plaque was launched with Pioneer 10 on March 2, 1972, and the second followed with Pioneer 11 on April 5, 1973.

In May 2017 a limited edition of 200 replicas engraved from the original master design at Precision Engravers was made available in a Kickstarter Campaign, which also offered laser-engraved replicas.[3]

Physical properties

- Material: 6061 T6 gold-anodized aluminium

- Width: 229 mm (9 inches)

- Height: 152 mm (6 inches)

- Thickness: 1.27 mm (0.05 inch)

- Mean depth of engraving: 0.381 millimeters (381 μm) (0.015 inch)

- Mass: approx. 0.120 kilograms (120 g) (4.2 oz)

Symbolism

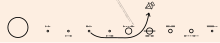

Hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen

At the top left of the plate is a schematic representation of the hyperfine transition of hydrogen, which is the most abundant element in the universe. The spin-flip transition of a hydrogen atom’s electron has a frequency of about 1420.405 MHz, which corresponds to a period of 0.704 ns. Light at this frequency has a vacuum wavelength of 21.106 cm (which is also the distance the light travels in that time period). Below the symbol, the small vertical line—representing the binary digit 1—specifies a unit of length (21 cm) as well as a unit of time (0.7 ns). Both units are used as measurements in the other symbols.[4]

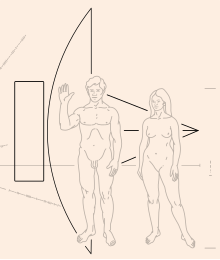

Figures of a man and a woman

On the right side of the plaque, a man and a woman are shown in front of the spacecraft.[5] Between the brackets that indicate the height of the woman, the binary representation of the number 8 can be seen (1000, with a small defect in the first zero). In units of the wavelength of the hyperfine transition of hydrogen this means 8 × 21 cm = 168 cm.

The right hand of the man is raised as a sign of good will. Although this gesture may not be understood, it offers a way to show the opposable thumb and how the limbs can be moved.[6]

Originally Sagan intended the humans to be shown holding hands, but soon realized that an extraterrestrial might perceive them as a single creature rather than two organisms.[6]

The original drawings of the figures were based on drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and Greek sculptures.[6]

The woman's genitals are not depicted in detail; only the Mons pubis is shown. It has been claimed that Sagan, having little time to complete the plaque, suspected that NASA would have rejected a more intricate drawing and therefore made a compromise just to be safe.[7] Carl Sagan said that the decision to not include the vertical line on the woman's genitalia (pudendal cleft) which would be caused by the intersection of the labia majora was due to two reasons. First, Greek sculptures of women do not include that line. Second, Carl Sagan believed that a design with such an explicit depiction of a woman's genitalia would be considered too obscene to be approved by NASA.[6] According to the memoirs of Robert S. Kraemer, however, the original design that was presented to NASA headquarters included a line which indicated the woman's vulva,[8] and this line was erased as a condition for approval of the design by John Naugle, former head of NASA's Office of Space Science and the agency's former chief scientist.[8]

Relative position of the Sun to the center of the Galaxy and 14 pulsars

The radial pattern on the left of the plaque shows 15 lines emanating from the same origin. Fourteen of the lines have corresponding long binary numbers, which stand for the periods of pulsars, using the hydrogen spin-flip transition frequency as the unit. Since these periods will change over time, the epoch of the launch can be calculated from these values.

The lengths of the lines show the relative distances of the pulsars to the Sun. A tick mark at the end of each line gives the Z coordinate perpendicular to the galactic plane.

If the plaque is found, only some of the pulsars may be visible from the location of its discovery. Showing the location with as many as 14 pulsars provides redundancy so that the location of the origin can be triangulated even if only some of the pulsars are recognized.

The data for one of the pulsars is misleading. When the plaque was designed, the frequency of pulsar "1240" (now known as J1243-6423) was known to only three significant decimal digits: 0.388 second.[1] The map lists the period of this pulsar in binary to much greater precision: 100000110110010110001001111000. Rounding this off at about 10 significant bits (100000110100000000000000000000) would have provided a hint of this uncertainty. This pulsar is represented by the long line pointing down and to the right.

The fifteenth line on the plaque extends to the far right, behind the human figures. This line indicates the Sun's relative distance to the center of the galaxy.

The pulsar map and hydrogen atom diagram are shared in common with the Voyager Golden Record.

Solar System

At the bottom of the plaque is a schematic diagram of the Solar System. A small picture of the spacecraft is shown, and the trajectory shows its way past Jupiter and out of the Solar System. Both Pioneers 10 and 11 have identical plaques; however, after launch, Pioneer 11 was redirected toward Saturn and from there it exited the Solar System. In this regard the Pioneer 11 plaque is somewhat inaccurate. The Saturn flyby of Pioneer 11 would also greatly influence its future direction and destination as compared to Pioneer 10, but this fact is not depicted in the plaques.

Saturn's rings could give a further hint to identifying the Solar System. Rings around the planets Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune were unknown when the plaque was designed; however, unlike Saturn, the ring systems on these planets are not so easily visible and apparent as Saturn's. Pluto was considered to be a planet when the plaque was designed; in 2006 the IAU reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet and then in 2008 as a plutoid. Other large bodies classed as dwarf planets, such as Eris, are not depicted, as they were unknown at the time the plaque was made.

The binary numbers above and below the planets show the relative distance to the Sun. The unit is 1/10 of Mercury's orbit. Rather than the familiar "1" and "0", "I" and "-" are used.

Silhouette of the spacecraft

Behind the figures of the human beings, the silhouette of the Pioneer spacecraft is shown in the same scale so that the size of the human beings can be deduced by measuring the spacecraft.

Criticism

One of the parts of the diagram that is among the easiest for humans to understand may be among the hardest for the extraterrestrial finders to understand: the arrow showing the trajectory of Pioneer. An article in Scientific American[9] criticized the use of an arrow because arrows are an artifact of hunter-gatherer societies like those on Earth; finders with a different cultural heritage may find the arrow symbol meaningless.

Art critic and activist Craig Owens said that sexual bias is exhibited by the choice to make the man in the diagram perform the wave gesture to greet the extraterrestrials while the woman in the diagram has her hands at her sides.[10] Feminists also took issue with this choice for the same reason.[11]

Carl Sagan regretted that the figures in the finished engraving failed to look panracial. Although this was the intent, the final figures appeared Caucasian.[11] In the original drawing, the man was drawn with an "Afro" haircut, so an additional African physical trait would be included in the man to make the figures look more panracial, but that detail was changed to a "non-African Mediterranean-curly haircut" in the finished engraving.[12] Furthermore, Carl Sagan said that Linda Sagan intended to portray both the man and woman as having brown hair, but the hair being only outlined rather than being both outlined and shaded made the hair appear blonde instead.[13] Other people had different interpretations of the race of people depicted by the figures. Whites, blacks and Asians each tended to think that the figures resembled their own racial group, so, although some people were proud that their race appeared to have been selected to represent all of humankind, others viewed the figures as "terribly racist" for "the apparently blatant exclusion" of other races.[8]

Linda Sagan decided to make the figures nude to address the problem of the type of clothes they should wear to represent all of humanity and to make the figures more anatomically educational for extraterrestrials, but their nudity was viewed as pornographic by the American media.[8] According to astronomer Frank Drake, there were many negative reactions to the plaque because the human beings were displayed naked.[14] When images of the final design were published in American newspapers, one newspaper published the image with the man's genitalia removed and another newspaper published the image with both the man's genitalia and the woman's nipples removed.[6] In one letter to a newspaper, a person angrily wrote that they felt that the nudity of the images made the images obscene.[6] In contrast, in another letter to the same newspaper, a person was critical of the prudishness of the people who found depictions of nudity to be obscene.[6]

Fiction

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (May 2017) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

- Star Trek

- In the Star Trek Encyclopedia paperback – International Edition, October 1, 1999, the plaque is shown with Pioneer launching from the second planet rather than the third.

- In the science fiction film Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the plaque's diagram is fleetingly shown during Spock's mindmeld with V'ger, a transformed NASA space probe, Voyager 6. This style of plaque was not used in the two actual NASA probes in the Voyager program.

- In Star Trek: Voyager, the plaque appears on the viewing screen when a signal is sent by Rain Robinson trying to communicate with Voyager. 16 minutes and 28 seconds into episode 8 season 3 Future's End.

- In the science fiction film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, the plaque is shown attached to a Pioneer probe floating in space—just before the probe is intercepted and destroyed by a bored Klingon ship captain, who scoffs "Shooting space garbage is no test of a warrior's mettle." However the plaque is erroneously depicted as facing outwards rather than inwards.

- In the Star Trek novel Federation, a character mentions that humans had shown copies of the plaque to several alien races they encountered, but none had been able to decode it.

- Other

- In "The Message," an episode of the science fiction series The Outer Limits, a deaf woman was featured receiving alien signals through her cochlear implant, prompting her to write out Xs, 1s, and 0s on paper. When put together, the Xs turned into the images of the man and woman from the plaque, along with an extraterrestrial humanoid raising a hand in a peaceful gesture.

- On her album United States Live, American performance artist Laurie Anderson contemplates extraterrestrials finding the plaque and asks "do you think that they will think his arm is permanently attached in this position?"

- In the Futurama episode "Godfellas," the robot Bender finds himself doomed to drift through space, during which time he etches a modified version of the Pioneer plaque, with himself towering menacingly over the human figures, so that "When I'm found in a million years, people will know what the score was."

- In Buck Rogers season 1, episode 15 "Ardala Returns," Princess Ardala constructs a fake probe (allegedly launched in 1996) that utilizes a copy of the plaque in order to trick Buck into thinking the probe was from his own time period — the distant past.

- In the L. Ron Hubbard novel Battlefield Earth, it is mentioned by the principal alien character that his race's conquest of Earth was made possible by their discovery of a space probe "that gave full directions to the place, had pictures of man on it and everything".

- In "Beware My Cheating Bart" (18th episode of Season 23) of The Simpsons, the plaque was briefly shown at the end of the episode. It was depicted with an extraterrestrial holding the plaque upside down, obviously confused by its strange depictions.

- The plaque is used as the artwork for the album Aufheben by The Brian Jonestown Massacre and for Accept the Signal by Regular Fries.

- A drawing which bears a strong likeness to the one depicted in the plaque was used as the artwork for Norwegian avant-garde metal band Arcturus' album Sideshow Symphonies.

- A character in Kamen Rider Gaim uses a package containing language dictionaries and a modified version of the plaque to later communicate with an other-dimensional sentient race.

- In the TV show Eureka, on episode 5 of season 2 (Duck Duck Goose), the plaque is shown as part of the debris that lands on Earth.

- In the TV show The Big Bang Theory, on episode 21 of season 8 (The Communication Deterioration), the plaque is mentioned when they are discussing ideas about sending a message to alien races in space.

- In the video game by Paradox Development Studio, Stellaris, one of the scientific missions discovers the plaque on an alien world in the distant future.

- The Pioneer plaque appears in the booklet of David Bowie's 2016 album Blackstar, on the page for the song "Girl Loves Me".

- The Pioneer plaque appears in 01 - Welcome / Orientation briefing video of the Mass Effect Andromeda Initiative website. [15]

- 17776 has Pioneer 10 (named Ten in the story) as a sentient being who is made fun of by Pioneer 9 (Nine) and Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) for being sent into space with a plaque displaying naked humans.

- In the Wii U title, Xenoblade Chronicles X, the plaque is seen in the opening cut scene, damaged and floating in midspace, before one of the alien ships that later approaches Earth.

- Edwin Morgan's poem, "Translunar Space March 1972", refers to Pioneer 10, and passes critical commentary on the images on the plaque: "A deodorized American man / with apologetic genitals and no pubic hair / holds up a banana-like right hand"[16]

See also

- Alien language

- Arecibo message

- Communication with extraterrestrial intelligence

- Lunar plaque

- Pioneer program

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI)

- Voyager Golden Record

References

- ^ a b Carl Sagan; Linda Salzman Sagan; Frank Drake (1972-02-25). "A Message from Earth" (PDF). Science. 175 (4024): 881–884. Bibcode:1972Sci...175..881S. doi:10.1126/science.175.4024.881. PMID 17781060.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) Paper on the background of the plaque. Pages available online: 1, 2, 3, 4. - ^ Pournelle, Jerry (April 1982). "The Osborne 1, Zeke's New Friends, and Spelling Revisited". BYTE. p. 212. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ King, Duane. "Pioneer Plaque: a Message from Earth". Kickstarter.com. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Rosenthal, Jake. "The Pioneer Plaque: Science as a Universal Language". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Send aliens modern messages of Earth's equality and diversity, say scientists". The Guardian. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sagan, C. (2009). Carl Sagan, Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective, Cambridge University Press pp. 22-25 ISBN 0-521-78303-8

- ^ Alan Fletcher, "The art of looking sideways", Phaidon Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7148-3449-1.

- ^ a b c d Wolverton, M. (2004). The Depths of Space: The Story of the Pioneer Planetary Probes Joseph Henry Press. pp. 79, 80 & 82. ISBN 0-309-53323-6

- ^ Ernst Gombrich ‘The Visual Image’, 1972 in Scientific American (eds [clarification needed]) Communication. San Francisco, California, Freeman, pp. 46–60; originally in a special issue of Scientific American, September 1972; republished in Gombrich (1982) The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, London, Phaidon, pp. 137–61.

- ^ Bogue, R. (1991). Mimesis in Contemporary Theory: (vol. 2) Mimesis, semiosis, and power. USA: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 176. ISBN 1-55619-150-2 (hb.) (v. 2 : US)

- ^ a b Achenbach, J. (1999). Captured by Aliens: The Search for Life and Truth in a Very Large Universe New York, NY: Citadel Press Books. pp. 92. ISBN 0-8065-2496-0

- ^ Gepper, A.C.T. (2012). Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century. New York, NY: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 297. ISBN 978-0-230-23172-6

- ^ Spangenburg, R. & Moser, K. (2004). Carl Sagan: A Biography USA: Greenwood Press. pp. 74. ISBN 0-313-32265-1

- ^ Cited in Carl Sagan, Murmurs of Earth, 1978, New York, ISBN 0-679-74444-4

- ^ https://www.masseffect.com/andromeda-initiative/

- ^ Collected Poems. Manchester: Carcanet Press. 1997. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-857541-88-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)

External links

- Hans Mark: Origin Story of Carl Sagan's Plaque on Pioneer 10 on YouTube – recording from 1994 interview

- Reading the Pioneer/Voyager Pulsar Map (Wm. Robert Johnston), updated 11 March 2003. Last accessed on 8 April 2006

- Communicating With Aliens – an article on the Pioneer plaques