Polish złoty

| Polski złoty (Polish) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| ISO 4217 | |||||

| Code | PLN (numeric: 985) | ||||

| Subunit | 0.01 | ||||

| Unit | |||||

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency belong(s) to the Slavic languages. There is more than one way to construct plural forms. | ||||

| Symbol | zł | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1⁄100 | Grosz | ||||

| Symbol | |||||

| Grosz | gr | ||||

| Banknotes | 10zł, 20zł, 50zł, 100zł, 200zł | ||||

| Coins | 1gr, 2gr, 5gr, 10gr, 20gr, 50gr, 1zł, 2zł, 5zł | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| User(s) | Poland | ||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | National Bank of Poland | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Mint | Mennica Polska | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Valuation | |||||

| Inflation | −0.5% | ||||

| Source | [1] (July 2016) | ||||

The złoty (pronounced [ˈzwɔtɨ] ;[2] sign: zł; code: PLN), which literally means "golden", is the currency of Poland. The modern złoty is subdivided into 100 groszy (singular: grosz; alternative plural form: grosze). The recognized English form of the word is zloty, plural zloty or zlotys.[3] The currency sign, zł, is composed of the Polish lower-case letters z and ł (Unicode: U+007A z LATIN SMALL LETTER Z & U+0142 ł LATIN SMALL LETTER L WITH STROKE).

As a result of inflation in the early 1990s, the currency underwent redenomination. Thus, on January 1, 1995, 10,000 old złotych (PLZ) became one new złoty (PLN). Since then, the currency has been relatively stable, with an exchange rate fluctuating between 2 and 4.5 złoty for a United States dollar.

Before the złoty

The predecessors of the złoty were the Polish mark (grzywna) and a kopa. Grzywna was a currency that was equivalent to approximately 210 g of silver, in the 11th century. It was used until sometime in the 14th century, when it gave way to the Kraków grzywna (approximately 198 g of silver). At the same time, first as the complement to grzywna, and then as the main currency, came a grosz and a kopa. Poland made grosz as the imitation of the Prague groschen; the idea of kopa came from the Czechs as well. A grzywna was worth 48 groszy; a kopa cost 60 groszy.[4][5][6]

First złoty

Kingdom of Poland and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The złoty (golden) is a traditional Polish currency unit dating back to the late Middle Ages. Initially, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the name was used for all kinds of foreign gold coins used in Poland, most notably Venetian and Hungarian ducats, (however, in Ukraine, Volyn and Galicia, the name for them were the золотий - golden).[7] One złoty at the very beginning of their introduction cost 12–14 groszy; however, groszy had less and less silver as time passed. In 1496 the Sejm approved the creation of a national currency, the złoty, and its value was set at 30 groszy, a coin minted since 1347 and modelled on the Prague groschen, and a ducat (florin), whose value was 1+1⁄2 złoty.[8] The 1:30 proportion stayed (1⁄2 of a kopa), but the grosz became cheaper and cheaper, because the proportion of silver in the coin alloy diminished by time. In the beginning of the 16th century, 1 złoty was worth 32 groszy; by the middle of the same century it was 50 groszy;[9] by the reign of Sigismund III Vasa 1 złoty was worth 90 groszy, while a ducat was worth 180 groszy.

The name złoty (sometimes referred to as the florin) was used for a number of different coins, including the 30-groszy coin called the polski złoty, the czerwony złoty (red złoty) and the złoty reński (the Rhine guilder), which were in circulation at the time. However, the value of the Polish złoty dropped over time relative to these foreign coins, and it became a silver coin, with the foreign ducats eventually circulating at approximately 5 złotych.

The matters were complicated by the extremely intricate system of coins, with denominations as low as +1⁄3 groszy and as high as 12,960 groszy fit into one coin. There were no usual decimal denominations we use today: the system used 4, 6, 8, 9 and 18 groszy, which are now most uncommon. Moreover, there was no central mint, and, apart from Warsaw mint, there were the Gdańsk, Elbląg and Kurland (Riga) separate mints which did not produce the same denomination coins with the same materials. For example, the szeląg had 1.3g of copper while minted in either Kraków or Warsaw, but the local Gdańsk and Elbląg mints made it using only 0.63g of copper. This facilitated forgeries and wreaked havoc in the Polish monetary system

Following the monetary reform carried out by King Stanisław II Augustus which aimed to simplify the system, the złoty became Poland's official currency and the exchange rate of 1 złoty to 30 groszy was confirmed. The king established the system which was based on the Cologne mark (233.855 g of pure silver). Each mark was divided into 10 Conventionsthaler of the Holy Roman Empire, and 1 thaler was worth 8 złotych (consequently, 1 złoty was worth 4 grosze. The system was in place until 1787. Two devaluations of the currency occurred in the years before the final partition of Poland.

After the third partition of Poland, the name złoty existed only in Austrian and Russian lands. Prussia had introduced the mark instead.

| Name | Value (in groszy) | Introduced by | Minted in | Material | Weight (in grams) | Photos or graphics | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| denar | 1⁄18–1⁄10 grosza | Bolesław I the Brave | 11th century – 1653 | After 1527: copper | 0.33 g (Sigismund III Vasa's coin);

0.53 g(John II Casimir) |

|

Smallest coin in use |

| ternar | 1⁄6 grosza | Władysław II Jagiełło | 14th century – 1407 (1414); 1526–1529; 1545–1548; 1623 | 1526 coins: silver(18%) alloy;

1623 coins: silver(7.8%) alloy; |

0.57 g | ||

| szeląg | 1⁄3 grosza | Stefan Batory | 1579–1627; 1659–1666; 1749–1792 | Silver alloy (15.929%); copper from 1658 | 1.13 g (Stefan Batory szeląg);

1.3 g (boratynka) 0.62 g(local coins, such as the Gdańsk grosz) |

|

The John Casimir szeląg is also called boratynka |

| półgrosz | 1⁄2 grosza | Władysław II Jagiełło | 1398 – early 17th century; 1766–1795 | In 1393–1414 (in Lwów): silver alloy (up to 56.2%); then 43.7%.

In Kraków: either heavier with 50% silver or lighter with 37.5% silver. From 1766 copper. |

Kraków: 1.58 g (50% silver) or 0.96 g (37.5% silver);

Stanisław II Augustus: 1.95 g |

|

|

| grosz srebrny | 1 grosz srebrny = 7+1⁄2 groszy miednych | Stanisław II Augustus | 1764–1795 | 36.7% silver alloy | 1.99 g | ? | |

| grosz

(grosz miedziany from Stanisław II Augustus' reign) |

1 grosz | Casimir III the Great | 1367–1849; 1918–present | Casimir III Great: brass coins; later copper | 1.3(Kurland grosz) or 3.4 grams("Kingdom" grosz);

3.89 g(Stanisław II Augustus) |

|

The base of the currency |

| półtorak | 1+1⁄2 grosza | Sigismund III Vasa | 1614-1660; in the John II Casimir Vasa and Augustus III reigns | Silver (46.9%) alloy | 1.09 g(Augustus III) |  |

Created as an intermediate between grosz and trojak |

| dwojak | 2 grosze | Sigismund II Augustus | Around 1520s; sporadically later; more minted at John II Casimir Vasa's reign; 1766–84; 1923–1939; 1954– | Sigismund I the Old: silver

Sigismund II Augustus: silver Stanisław II: 58.7% silver alloy |

1.8 g (Sigismund I the Old)

ca. 3.5 g (Sigismund II Augustus); 3.4 g(Stanisław II Augustus) |

||

| trojak | 3 grosze | Sigismund I the Old | 1528–1849 | Silver, most copper from Stanisław II Augustus' reign;

some Gdańsk coins are copper |

2.16 g("Kingdom" trojak)

1.53 g(Gdańsk trojak); 11.69 g(Stanisław Augustus) 1.52 g(silver Gdańsk and Toruń trojak) |

|

Also called "dutka", "babka", "dydek" in Lithuania |

| czworak | 4 grosze | Sigismund II Augustus | 1565–1568; 1614; 1766–95 | Silver;

55% silver alloy(Stanisław II Augustus) |

4.29 g;

5.51 g(Stanisław II Augustus) |

||

| szóstak | 6 groszy | Sigismund I the Old | 1528–1795 | Silver | 2.34 g(Toruń szóstak)

2.94 g(Gdańsk and Elbląg szóstak); 3.7 g(Kurland szóstak) 4.32 g("Kingdom" szóstak); in 1794-95 1.52 g |

|

|

| 2 złote [Stanisław II and Augustus III] | 8 groszy | Augustus III | 1753-1795 | 62.67% silver alloy | 9.35 g(Stanisław II)

7.31 g(Augustus III) |

||

| półurcie | 9 groszy | ? | ? | ? | ? | ||

| 10 copper Kingdom groszy | 10 groszy | Stanisław II Augustus | 1787-95 | 37.3% silver alloy | 2.49 g, then 4.48 g | ||

| ort | 18 groszy | Sigismund III Vasa | 1608–1766 | Silver | Augustus III reign:

5.84 g("Kingdom") 6.1 g or 7.7 g (Gdańsk) |

|

Coins of 1618 were minted by Stanisław Berman |

| półkopek | 30 groszy;

Stanisław II Augustus' złoty - 4 grosze |

Sigismund II Augustus | 1564–1841 | Silver alloy (49.955%) | 6.726 g(John III Sobieski)

5.84 g("Kingdom") or 6.1 g(Gdańsk) tymf; złotówka gdańska: 9.85 g |

|

From 1663 on also called tymf |

| kopa | 60 groszy = 2 złote | ? | ? | Silver | ? | ||

| półtalar | 15–120 groszy (de facto 15–290, more expensive as time passed) | Sigismund II Augustus | 1567–1794 | Silver | ca. 12.5 g;

14.62 g(Augustus III reign); 14.03 g, later 13.07 g(Stanisław II Augustus) |

|

|

| +2⁄3 of talar | only commemorative | Augustus III | 1738; 1747 | Silver | |||

| talar | 30–240 groszy (de facto 30–580, more expensive as time passed) | Sigismund I the Old | 1533; 1580–1795 | Silver;

83.3% silver alloy(from 1766) |

ca. 24.3–29.3 g |  |

|

| 2 talars | 480 groszy(de facto 1160 groszy) | Augustus III | 1740 | Silver | 58 g | ||

| dukat (florin) | 45–1,080 groszy | Władysław Łokietek | Early 14th century–1831 | Gold;

98.6% gold alloy(1766–95) |

3.46-3.5 g in the second half of XVIII century |    | |

| 2 ducats | Augustus III | 1753-4 | Gold | 7 g | |||

| 6 ducats | Augustus III | 1742 | Gold | 21 g | |||

| portugał | 10 ducats | Sigismund II Augustus | 1562–1652 | Gold | 35 g(Augustus III) |   | |

| 12 ducats | Augustus III | 1740 | Gold | 29.17 g | |||

| półaugustdor | 2+1⁄2 talars = 600 groszy (de jure); 1,450 groszy (de facto) | Augustus III of Poland | 1752–1756 | Gold | 3.32 g | ||

| augustdor | 5 talars = 1,200 groszy (de jure); 2,900 groszy (de facto) | Augustus III of Poland | 1752–1756 | Gold | 3.32 g | ||

| double augustdor | 10 talars = 2400 talars (de jure); 5800 groszy (de facto) | Augustus III of Poland | 1752–1756 | Gold | 13.3 g | ||

| półstanislasdor | 27 złotych | Stanisław II Augustus | 1764–1795 | Gold | 6.17 g | ||

| stanislasdor | 54 złotych | Stanisław II Augustus | 1794–1795 | Gold (83%) | 12.35 g |

The Kościuszko Insurrection and Russian part of Poland until 1807

On 8 June 1794 the decision of the Polish Supreme Council offered to make the new banknotes as well as the coins. 13 August 1794 was the date when the złoty banknotes were released to public. At the day there was more than 6.65 million złotych given out by the rebels. There were banknotes with the denomination of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 złotych (dated as of 8 June 1794), as well as 5 and 10 groszy, and 1 and 4 złoty coins (later banknotes, dated as of 13 August of the same year. Table)

However, it did not last for long: on 8 November, Warsaw was already held by Russia. Russians discarded all the banknotes and declared them invalid. Russian coins and banknotes replaced the Kościuszko banknotes, but the division on złote and grosze stayed. This can be explained by the fact the Polish monetary system, even in the deep crisis, was better than the Russian stable one, as Poland used the silver standard for coins. That is why Mikhail Speransky offered to come to silver monometalism ("count on the silver ruble") in his work План финансов (Financial Plans, 1810) in Russia. He argued that: "... at the same time ... forbid any other account in Livonia and Poland, and this is the only way to unify the financial system of these provinces in the Russian system, and as well they will stop, at least, the damage that pulls back our finances for so long."

Duchy of Warsaw

The złoty remained in circulation after the Partitions of Poland and the Duchy of Warsaw issued coins denominated in grosz, złoty and talar (plurals talary and talarów), worth 6 złoty. Talar banknotes were also issued. In 1813, while Zamość was under siege, Zamość authorities issued 6 grosze and 2 złote coins.

Congress Poland

On 19 November O.S. (1 December N.S.) 1815, the law regarding the monetary system of Congress Poland (in Russia) was passed, according to which the złoty stayed, but there was a fixed ratio of the ruble to the złoty: 1 złoty was worth 15 silver groszy, while 1 grosz was worth 1⁄2 silver kopeck. From 1816, the złoty started being issued by the Warsaw mint, denominated in grosze and złote in the Polish language, as well as the portrait of Alexander I and/or the Russian Empire's coat of arms:

- 1 and 3 grosze made from copper;(1815–49);

- 5 and 10 groszy out of billon;(1816–55);

- 1, 2, 5 and 10 złotych out of silver;(1816–55);

- 25 (the so-called złoty pojedyńczy, single złoty) and 50 (złoty podwójny; double złoty) złotych out of gold (1817–34).

At the same time kopecks were permitted to be circulated in Congress Poland. In fact foreign coins circulated (of the Austrian Empire and Prussia), and the Polish złoty itself was effectively a foreign currency. The coins were as well used in the western part of the Russian Empire, legally from 1827 (decision of the State Council).

In 1828 the Polish mint was allowed to print banknotes of denominations of 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 złotych, on the condition of their guaranteed exchange for coins at the will of Saint Petersburg. That meant that there should have been silver coins that had the value of 1⁄7 of banknotes in circulation.

November Uprising

At the time of the November Uprising, the rebels released their own "rebellion money" – the golden ducats and silver coins of the denomination of 2 and 5 złotych, with the revolutionary coat of arms, and the copper 3 and 10 groszy. The 1-złoty coin was as well released as a trial coin. The Polish bank, under the control of the rebels, having few precious metal resources in the reserves, released the 1 złoty banknote. They released the 5, 50 and 100 zł banknotes as well, all yellow. By August 1831 735 thousand złotych were released as banknotes. After the defeat of the uprising the decisions from 21 November (3 December) and 18 (30) December cancelled all the uprising monetary politics. All the coins were to be replaced by Russian coins, but it took a long time till the currency was circulating – only in 1838 was the usage of rebel money banned.

The last years of the first złoty of Congress Poland

At the same time the question arose about the future of the Polish złoty, as well as drastically limiting Polish banking autonomy. Russian finance minister Georg von Cancrin suggested to "value everything in rubles, not florins [złoty]".

There was a problem, however. The monetary system in the Russian Empire was still severely unbalanced. Banknotes, for example, cost much less to produce than their denomination. For that reason, the decision was taken to show both currencies on coins, which was a rather mild punishment for the November Uprising. From 1832 on the Petersburg and Warsaw mints decided to start minting new double-denominated coins. The exchange rate was 1 złoty to 15 kopecks.

In 1841 the main currency of Congress Poland became the Russian ruble.

From 1842, the Warsaw mint already issued regular-type Russian coins along with some coins denominated in both groszy and kopecks. At that time the złoty-to-ruble ratio changed again: 1 ruble was now worth only 2 złote.

The Warsaw mint still issued three coin types: double currency coins (up to 1850), złote and grosze (up to 1865), and the Russian Empire standard coins till 1865. From 1865 the Warsaw mint stopped making coins, and on 1 January 1868 the Warsaw mint was abolished.

The banknotes were changed much faster, as no Polish banknote was in circulation (at least officially). The Polish Bank started issuing Russian banknotes, denominated only in rubles and valid only in Congress Poland. At the same time the national credit banknotes, made in St. Petersburg, could be used everywhere in the Empire as usual Russian banknotes, as well in Poland.

The Free City of Kraków złoty

Between 1835 and 1846, the Free City of Kraków also used a currency, the Kraków złoty, with the coins actually being made in Vienna. There were 5 and 10 groszy coins and 1 złoty coins. They were all the same: the obverse had the coat of arms and the writing: WOLNE MIASTO KRAKÓW ("Free City of Krakow"), the reverse had the nominal and the year of production.

Poland without the złoty

From 1850, the only currency issued for use in Congress Poland was the ruble consisting of Russian currency and notes of the Bank Polski. The monetary system of Congress Poland was unified with that of the Russian Empire following the failed January Uprising in 1863. However, the gold coins remained in use until the early 20th century, much like other gold coins of the era, most notably gold rubles (dubbed świnka, or "piggy") and sovereigns. Following the occupation of Congress Poland by Germany during World War I in 1917, the ruble was replaced by the marka (plurals marki and marek), a currency initially equivalent to the German Papiermark.

Polish currency in 1918–24

New Poland started releasing new currency – Polish marks, after the defeat of the German Empire and Austro-Hungary. The first banknotes had either Tadeusz Kościuszko (5, 10, 100, 1000 marks) or Queen Jadwiga (10 and 500 marks). 1 and 20 marks also circulated, but they showed nobody on the banknotes.

The Polish marka was extremely unstable because of the constant wars with its neighbours. Attempts to reduce the expenditures of Polish budget were vain – all the money gained went to conduct war with the USSR. To complicate the matters, those attempts did not please the elite, which ruled the country. The government's actions were not popular at all, so the taxes did not rise significantly, in order to avoid popular resentment. Even worse, the territories that made up Poland were rightly coined "the country of three parts", as each part of Poland developed differently during the 123 years after Stanisław II Augustus' abdication, with post-Prussian territories the best developed, and Austrian Galicia and Russian Kresy the worst.

The last attempt to save the Polish marka was made in 1921, when Jerzy Michalski made out his own plan to raise taxes and reduce expenditure. The Sejm accepted it, albeit with many amendments. Realisation of that plan did not succeed, and it had only short-term influence.

This disrupted the whole economy of Poland, and galloping inflation began. The 1⁄2 marek and 5,000 marek banknotes became worthless in two years. As hyperinflation progressed, Poland came to print 1, 5 and 10 million mark banknotes. However, they were quickly almost valueless. 10 million marks cost only US$1,073 in January 1924. Immediate action was needed. Władysław Grabski was invited to stop the pending hyperinflation. As a result, the second Polish złoty was created.

Second złoty

Grabski monetary reform

The złoty was reintroduced as Poland's currency by Grabski in 1924, following the hyperinflation and monetary chaos of the years following World War I. It replaced the marka at a rate of 1 złoty = 1,800,000 marek and was subdivided into 100 groszy, instead of 30 groszy, as it had been earlier. 1 złoty was worth 0.2903 grams of gold, and 1 US dollar cost 5.18 złotych. New coins had to be introduced, but were not immediately minted or in circulation. The temporary solution of the problem was ingenious. 500,000 marek banknote were cut in two, and on each side there were overstamps that showed they were 1 grosz "coins". Similarly 10,000,000 marek notes were divided and overprinted to make two "coins" each worth 5 groszy. This was an emergency measure to provide the population with a form of the new currency.

Transition to złoty

When the second złoty was created, it was pegged to the US dollar. The Sejm was a weak in its financial control. Yet political parties demanded the government spend more money than had been projected in the budget.

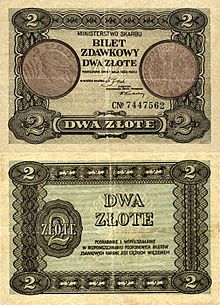

Budget defecit ballooned and inflation was developing coming out of control. The government struggled to cut expenditure, and as a result often came into conflict with the Sejm. However, the government could not allow hyperinflation to reoccur. To achieve that, the government authorised issue of securities, which went along with the temporary "bilety zdawkowe", coins and złoty banknotes printed in 1919.

| Picture | Denomination | Size | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | Date of print | Date of withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 złoty | 93×63 | Yellow | Tadeusz Kościuszko, denomination in words, date of print | Coat of arms, denomination in number | — | 28 February 1919 | 31 January 1940 |

|

2 złote | 115×80 | Blue | Denomination in number | — | |||

|

5 złotych | 125×80 | Bright yellow,

orange |

Józef Poniatowski, denomination in words, date of print | Denomination in words, coat of arms | — | 28 February 1919

15 July 1924 | |

| 10 złotych | 150×88 | Yellow | Tadeusz Kościuszko, denomination in words, date of print | Some agricultural products[dubious – discuss] | As portrait | 28 February 1919 (not released in public) | ||

|

Pink | 28 February 1919, 15 July 1924 | ||||||

| 20 złotych | 160×97 | White, red around the coat of arms and watermark | Denomination in numbers, coat of arms | |||||

|

50 złotych | 165×102 | Brown, yellow around denomination in words | 28 February 1919 | ||||

|

100 złotych | 172×103 | Blue | |||||

|

500 złotych | 180×110 | Violet and olive | |||||

|

1000 złotych | 183×111 | Brown | 28 February 1919 (extremely rare, not released in public) | ||||

|

5000 złotych | 190×113 | Different shades of green | 28 February 1919 (not released in public) | ||||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||

| Picture | Denomination | Size | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Date of print | Amount

printed/ overprinted |

Date of withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 grosz | 156×80 | Gray, red overprint | Image of 1 grosz coin, | Notation from the Polish Bank | 28 April 1924 | 49,171,000 | 31 January 1925 |

|

5 groszy | 199×92 | Gray, red overprint | Image of 5 groszy coin, | 11,361,000 | |||

| 10 groszy | 68×46 | Blue | Image of 10 groszy coin;

Sigismund's Column, in front of the Royal Castle in Warsaw |

27,144,000 | ||||

|

20 groszy | 79×49 | Brown | Image of 20 groszy coin; Nicolaus Copernicus Monument, Warsaw | 19,872,000 | |||

|

50 groszy | 85×53 | Red | Image of 50 groszy coin; Józef Poniatowski Monument, Warsaw | 18,839,000 | |||

|

2 złote | 113×80 | Olive | Denomination, date of print; image of the 2 zł commemorative coin (woman with a bunch of cereals) | Denomination; notation from the Polish Bank | 1 May 1925 | 50 mln | 31 March 1928

(lapsed 30 June 1930) |

|

5 złotych | 130×80 | Olive and yellow | Denomination, date of print; image of the 5 zł commemorative Constitution coin | Notation from the Polish bank, coat of arms | 59,709,000 | 3 June 1929(lapsed 30 June 1930) | |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||

By the end of 1925 the Polish government was unable to redeem the released securities. The Polish economy was on the brink of collapse.

Despite the crisis, Grabski refused to accept foreign help, because he was concerned Poland would become dependent on the League of Nations. The Polish PM thought that after the złoty stabilised, foreign financiers would be persuaded to give credits and make investments on more favourable conditions than were recently on offer. However, deep-rooted lack of confidence in the Polish economy had made these expectations unrealisable. Grabski's government was forced to sell some of the country's property on unfavourable conditions, without any significant effects. Eventually, the złoty depreciated some 50% from its 1923 value and Grabski resigned as Prime Minister. However renewed hyperinflation was averted.

| Pictures | Denomination | Diameter(mm) | Thickness(mm) | Mass(g) | Composition | Obverse | Reverse | Introduced | Issued | Withdrawn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 grosz | 14.7 | 1.01 | 1.5 | bronze | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a simple plant ornament | 1923 | 1923; 1925 1927

1928 1930-1939 |

1939 |

|

2 grosze | 17.6 | 0.96 | 2 | brass | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a simple plant ornament | 1923 | 1923 | 1939 |

| 2 grosze | 17.6 | 0.98 | 2 | bronze | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a simple plant ornament | 1923 | 1925 1927 1928

1930-1939 |

1939 | |

|

5 groszy | 20 | 1.12 | 3 | brass | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a simple plant ornament | 1923 | 1923 | 1939 |

| 5 groszy | 20 | 1.14 | 3 | bronze | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a simple plant ornament | 1923 | 1925 1928 1930

1931 1934-1939 |

1939 | |

|

10 groszy | 17.6 | 0.92 | 2 | nickel | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a complicated bush ornament | 1923 | 1923 | 1939 |

|

20 groszy | 20 | 1.07 | 3 | nickel | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a complicated bush ornament | 1923 | 1923 | 1939 |

|

50 groszy | 23 | 1.35 | 5 | nickel | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with a complicated bush ornament | 1923 | 1923 | 1939 |

|

1 złoty | 25 | 1.6 | 7 | nickel | Polish coat of arms' eagle, inscription: "Rzeczpospolita Polska" and the year of minting | denomination with an ornament | 1929 | 1929 | 1939 |

| Pictures | Denomination | Dimension(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | Date of introduction | Date of printing | Date of withdrawal | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 złoty | 108×60 | brown | Bolesław I the Brave, denomination, the "Bank of Poland" nad "Government note" inscriptions, date and place of issue | Denomination | As portrait | 1 October 1938 | 20 May 1940 | Leonard | |

|

2 złote | 102×63 | Gray-yellow | Denomination, portrait of a Doubravka of Bohemia, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Denomination, Polish coat of arms | Value(2 zł) | 26 February 1936 | Zdzisław Eichler | ||

|

5 złotych | 127×83 | Olive, yellow edges | Portrait of a man[who?], denomination, place and date of issue | A miner in the tunnel, denomination | - | 1 May 1925 | 1 May 1925, 25 October 1926 | Wacław Borowski | |

|

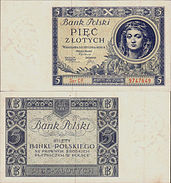

144×78 | Blue | Denomination, portrait of a woman[who?], the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Denomination, coat of arms, "Bank of Poland" inscription | Sigismund I the Old | 2 January 1930 | 2.01.1930 or 26.02.1936 | Ryszard Kleczewski | ||

|

10 złotych | 160×80 | Light brown | Denomination, pictures of saints, coat of arms, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A woman with a model ship in her hands, a worker and a female peasant with a bunch of wheat | Bolesław I the Brave, 10 ZŁ | 20 July 1926 | 20 July 1926, 20 July 1929 | Zdzisław Eichler | |

|

158×80 | Green | Denomination, a picture of a woman[who?], the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A road in the field that passes between the trees | As portrait | Never introduced | 2 January 1928 | ? | ||

|

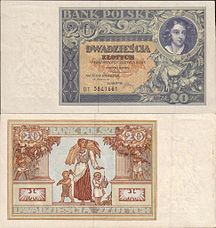

20 złotych | 170×94 | Obverse: brown, turquoise edges of picture; reverse: violet | A female peasant with a bunch of wheat and a male with a spade, denomination, "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Bank of Poland buildings: the one at the left is the former bank building on the Plac Bankowy; the newer one on the Bielańska street. | Casimir III the Great, 20 ZŁ | 1 March 1926 | 1 March 1926, 20 June 1931 | Zygmunt Kamiński | |

|

163×86 | Violet | Portrait of a young girl, denomination, coat of arms, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Morskie Oko lake | As portrait | Never introduced | 2 January 1928 | ? | ||

|

170×94 | Obverse: brown, light blue edges of picture; reverse: blue | Fortuna with a bunch of wheat and Hermes with a spade, denomination, "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Bank of Poland buildings: the one at the left is the former bank building on the Plac Bankowy; the newer one on the Bielańska street. | Casimir III the Great, 20 ZŁ | 1 September 1929 | Zygmunt Kamiński | |||

|

163×86 | Blue obverse, light green reverse | Portrait of Emilia Plater, denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A female peasant with a bunch of wheat and two boys, one of which holding a ship, other a hammer, coat of arms and denomination | Casimir III the Great, 20 ZŁ | 20 June 1931 | Ryszard Kleczewski | |||

|

Grey and blue | Emilia Plater, a woman with two daughters on the left with flowers, coat of arms, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Wawel Castle, Kraków, a figure of an architect and a poet (symbolize knowledge) | As portrait and denomination | 11 November 1936 | Wacław Borowski | ||||

|

50 złotych | 188×99 | green, blue and brown | Fortuna with a bunch of wheat and Hermes with a rod of Asclepius, denomination, "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Bank of Poland buildings: the one at the left is the former bank building on the Plac Bankowy; the newer one on the Bielańska street. | Stefan Batory, 50 złotych | 28 August 1925 | 28 August 1925, 1 September 1929, | Zygmunt Kamiński | |

|

169×92 | green | Jan Henryk Dąbrowski portrait, coat of arms, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A peasant with a bunch of wheat, two women holding a ship, a boy with an airplane and a worker with a hammer | As portrait and denomination | Never introduced | 11 November 1936 | Wacław Borowski | ||

|

100 złotych | 175×98 | Brown | Józef Poniatowski's portrait, denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A picture of an oak representing the history of Poland | Queen Jadwiga, 100 ZŁ | 2 June 1932 | 2 June 1932, 9 November 1934 | Józef Mehoffer | |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||||

Poland's economy weakened further to the point it was evident that the system could no longer function. The crisis climaxed in November 1925 leading to the Sanacja coup d'état.

Piłsudski's reforms

In May 1926 a coup d'état was effected. It resulted in Józef Piłsudski becoming the authoritarian leader of Poland. Almost immediately the budget was stabilised. Tax incomes rose significantly, credits was received from the USA, and the Bank of Poland's policy came more strongly under the government's control. These developments prevented the Polish economy's further deterioration.

As had happened earlier in the case of both Austria and Hungary, a special monitoring commission arrived in Poland to analyse the economic situation. The commission was headed by Edwin W. Kemmerer, an American economist and "money doctor".

The złoty started to stabilise in 1926 (thanks chiefly to significant exports of coal), and was re-set on the dollar-złoty rate 50% higher than in 1924. Up to 1933 złoty was freely exchanged into gold and foreign currencies. From these developments the government concluded adopted the Gold Standard for its currency.

In 1924–1925 the banks experienced large capital outflows, but by 1926 people were investing actively in the banks. The economic progress built on increased demand for and exports of coal slowed down because of over-valued złoty during 1927. As a result, imports became relatively cheaper as compared to exports, and the Balance of Trade trade balance turned to negative. Again, Poland plunged into crisis. In total, the economic growth in years 1926 to 1929 was not strongly felt. The main reason for that was the decline of industry, which was influenced by declining demand for Polish items. The crisis deepened with the Great Crisis of 1929–1932 and lasted until the mid-30s.

Polish złoty in 1930s

Poland entered another economic crisis, causing the government again to attempt reduction of its budget deficit by cutting public expenditure other than for military purposes. Despite cutting spend by a third, deficit persisted. Tax income that should have been used to lead the country out of crisis was instead financing the debt burden. Money required to stimulatee the economy was devoted by the government to creditors and foreign banks. Further spending cuts necessitated Poland importing less and exporting more. Import tariffs were increased again for foreign products, while subsidies were given to exporters.

In 1935 Piłusdski died, and the power passed to the generals. They were very disturbed by the crisis. Poland was still an agarian country with 61% of the population involved in 1931. To reform the economy, the government was thinking about further intervention. As a result between 1935 and 1939, Poland nationalised its major industries, initiating the changes the communists complteted after 1945. Volumes of produced goods output from state-owned factories exceeded expectations. The result was instant - the economy stabilised, and fears of further złoty devaluation reduced while rapid growth was seen. However, World War II abruptly terminated all prosperity. With the Russian invasion from the east the government had to flee the country. Already in emigration, the government released new banknotes of the denomination of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 złotych which were dated by 15 or 20 August 1939 and were mostly cyan, blue or blue-green (with the exception of 1, 2, 10 and 100 złotych). These were printed in the USA but never released.

| Pictures | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | Date of print | Designer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 złoty | 72×45 | Bright red | Denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Denomination | None | 15 August 1939 | Włodzimierz Vacek |

|

2 złote | 82×51 | Bright green | Denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Denomination, ornament[which?] | |||

|

5 złotych | 97×60 | Blue to cyan | Denomination, portrait of a woman in the traditional costume, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Denomination | |||

|

10 złotych | 141×67 | Red | Denomination, a picture of a woman with a necklace, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Płock Cathedral | As portrait | Edouard Meronti | |

|

20 złotych | 153×75 | Grey to blue | Denomination, a picture of a female Silesian with a cross, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | A power plant, behind the typically rural landscape, with haystacks | Edmund Dulac | ||

|

Obverse: different shades of blue, reverse: grey | Denomination, a picture of a girl in the traditional costume, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Saintmost Trinity Church in Leszczyny(now in Palowice) | - | 20 August 1939 | ? | ||

|

50 złotych | 163×80 | cyan | A mountain peasant(góral), mountain flowers motive, denomination, | Morskie Oko lake, coat of arms | As portrait and denomination | 15 August 1939 | Clément Serveau |

|

50 złotych | A female peasant with a sickle and a bunch of cereals | Dunajec River Gorge | - | 20 August 1939 | ? | ||

|

100 złotych | 171×86 | Brown | A portrait of a Mazury peasant, denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Landscape nearby the Tyniec, near Kraków | Portrait of a female on 50 zł(20.08.1939) | 15 August 1939 | Clément Serveau |

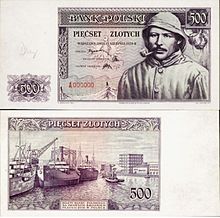

|

500 złotych | 182×89 | Grey | A portrait of a fisherman with a pipe, denomination, the "Bank of Poland" inscription, date and place of issue | Port in Gdynia | Edouard Meronti | ||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||

| Denomi-nation | Date of release | Metal | Mass | Diameter | In circulation | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Paris | London | Warsaw | Birming-ham | Phila-delfia | Obverse picture | Reverse picture |

| 1 złoty | 1924-5 | Silver(75% alloy) | 5 | 23 | 1924-1939 | rifled | A portrait of a woman with bunches of cereal.[10] | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 16 mln | 24 mln |  |

| |||

| 2 złote | 1924-5 | Silver(75% alloy) | 10 | 27 | 1924-1939 | rifled | A portrait of a woman with bunches of cereal.[10] | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 8.2 mln

(1924) |

1.2 mln

(1924) |

8 mln (1924);

5.2 mln (1925) |

|

| ||

| 2 złote | 1932-4 | Silver(75% alloy) | 4,4 | 22 | 1932-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Polonia - a woman signifying Poland.[11] Often mistaken for "a woman in a wreath", "Queen Jadwiga" or "Wanda" | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 25.2 mln |

|

| ||||

| 2 złote | 1934

1936 |

Silver(75% alloy) | 4,4 | 22 | 1932-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Józef Piłsudski.[10] | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 10.5 mln |

|

| ||||

| 2 złote | 1936 | Silver(75% alloy) | 4,4 | 22 | 1936-1939 | rifled | A picture of "Dar Pomorza" yacht, to commemorate 15 years of Gdynia port foundation.[12] | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 3,918,000 |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych2 | 1928,

1930-2 |

Silver(75% alloy) | 18 | 33 | 1928-1939 | SALUS REIPUBLICAE SUPREMA LEX1 | From Nika(Win) series.[13] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 28.7 mln |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych | 1930 | Silver(75% alloy) | 18 | 33 | 1928-1939 | SALUS REIPUBLICAE SUPREMA LEX1 | Consacred to the 1830 November Uprising.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 1,000,200 |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych | 1928,

1930-2 |

Silver(75% alloy) | 11 | 28 | 1932-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Polonia - a woman signifying Poland.[11] Often mistaken for "a woman in a wreath", "Queen Jadwiga" or "Wanda" | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 3 mln | 12,250,000 |

|

| |||

| 5 złotych | 1934 | Silver(75% alloy) | 11 | 28 | 1934-39 | rifled | Portrait of Józef Piłsudski[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; "orzeł strzelecki"; year of minting | 300,000 |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych | 1934-6,

1938 |

Silver(75% alloy) | 11 | 28 | 1934-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Józef Piłsudski.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 9,599,400 |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych | 1936 | Silver(75% alloy) | 11 | 28 | 1936-1939 | rifled | A picture of "Dar Pomorza" yacht, to commemorate 15 years of Gdynia port foundation.[12] | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 1 mln |

|

| ||||

| 5 złotych | 1925 | See right | 21.1 | 37 | 1925-1939 | rifled | Two sitting men, holding a Book (Constitution) | Polish Coat of Arms, inscriptions: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting | 100 in pinchbeck, 60 in brass, 2 in gold,

100 in 10% silver alloy |

| |||||

| 10 złotych | 1925 | Gold | 3,23 | 19 | 1925-39 | rifled | Portrait of Bolesław I the Brave.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 50,350 |

|

| ||||

| 10 złotych | 1933 | Silver(75% alloy) | 22 | 34 | 1933-39 | rifled | Portrait of Romuald Traugutt | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 200,000 |

|

| ||||

| 10 złotych | 1932-3 | Silver(75% alloy) | 22 | 34 | 1932-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Polonia - a woman signifying Poland.[11] Often mistaken for "woman in a wreath", "Queen Jadwiga" or "Wanda" | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 6 mln | 5.9 mln |

|

| |||

| 10 złotych | 1933 | Silver(75% alloy) | 22 | 34 | 1933-1939 | rifled | Portrait of John III Sobieski.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 300,000 |

|

| ||||

| 10 złotych | 1934 | Silver(75% alloy) | 22 | 34 | 1934-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Józef Piłsudski.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; "orzeł strzelecki"; year of minting | 300,000 |

|

|||||

| 10 złotych | 1934-9 | Silver(75% alloy) | 22 | 34 | 1934-1939 | rifled | Portrait of Józef Piłsudski.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 17,142,000 |

|

| ||||

| 10 złotych | 1934 | Silver(75% alloy); exist in iron and pinchbeck | 22 | 34 | 1934-1939 | rifled | Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska, year of minting; | 100 in each metal | |||||||

| 10 złotych | 1925 | Bronze or silver | 20,5 | 3,4(bronze)

4,2(silver) |

1925-39 | rifled | Two heads of women | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 100 in bronze, 50 in silver | ||||||

| 20 złotych | 1925 | Gold; exist in copper and nickel | 6,451 | 21 | 1925-39 | rifled | Portrait of Bolesław I the Brave.[10] | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting |

|

| |||||

| 20 złotych | 1925 | Bronze; silver | 6.5(bronze)

5.6(silver) |

21 | 1925-1939 | ? | "RP" design | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting, denomination | 100 bronze; 50 aluminium | ||||||

| 20 złotych | 1925 | Bronze, copper or silver; gold | 4.5(copper)

5.85(bronze) 4.32(silver) |

21 | 1925-1939 | ? | Portrait of Polonia - a woman signifying Poland.[11] Often mistaken for "woman in a wreath", "Queen Jadwiga" or "Wanda" | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 105(bronze)

12(silver) 10(copper) 5(gold) |

||||||

| 50 złotych | 1925 | Copper(exist as well in lead and aluminium) | 10,9 | 25 | 1925-39 | ? | A kneeling knight | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms, inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | 105 | ||||||

| 100 złotych | 1925 | Bronze or silver | Bronze: 3.5; Silver: 4.15 | 25 | 1925-39 | ? | Nicolaus Copernicus; denomination | Denomination, Polish Coat of Arms(squared), inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska; year of minting | |||||||

General Government

When German invaders established the General Government, they withdrew the 100 złotych banknotes from 1932 and 1934 and 500 złotych banknotes from 1919. The banknotes had to be accounted on the deposits of the people who gave them to the bank.

The 100 złotych banknotes were overstamped in red with: "Generalgouvernement / für die besetzen polnischen Gebiete" (The General Government / for the occupied Polish territories). It was massively counterfeited.

A little later the bank division of the Główny Zarząd Kas Kredytowych Rzeszy Niemieckiej was organized. It started to print the Reichsmarks, but later, on December 15, 1939, a decision came to create the new Bank Emisyjny (Emissary Bank) in Kraków, as the Bank Polski officials fled to Paris. It started working on 8 April 1940.

In May 1940, old banknotes of 1924–1939 were overstamped by the new entity. Money exchange was limited per individual; the limits varied according to the status of the person. The fixed exchange rate 1 Reichsmark = 2 złote was established. A new issue of notes appeared in 1940-41. The General Government also issued coins (1, 5, 10 and 20 groszy in zinc, 50 groszy in nickel-plated iron or iron), using similar designs to earlier types but with cheaper metals (mainly zinc-copper alloy). 1, 5, 10 and 20 groszy coins were dated 1923 and 50 groszy were dated 1938.

Banknotes were also issued, called unofficially "młynarki" (from the name of President Feliks Młynarski) or "krakowiaki" (from the place of release), in the denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 złotych. 1000 złotych did not come into public circualtion at all, and only reconstructions survive (although shown below). The total amount of them was approximately 10,183 million złotych. Additional 20 millions were manufactured by the conspiratory typography of the Union of Armed Struggle. From summer 1943 the Home Army received the złote produced in Great Britain.

| Pictures | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Averse | Reverse | Date of print | Date of withdrawal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|

1 złoty | 99×65 | Dark green-gray | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription | 1 March 1940, 1 August 1941 | 10 January 1945 |

|

|

2 złote | 110×68 | Olive | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date, a peasant picture | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription | ||

| |

|

|File:5 zł 1940 rewers.jpg | 5 złotych | 150×82 | Dark green | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date, peasant on white margin, Doubravka of Bohemia | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription | ||

| |

|

| |

|

10 złotych | 170×85 | Brown | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date, the saints' pictures, head of a woman | The Chopin Monument in Warsaw | 1 March 1940 | |

| |

|

|

|

20 złotych | 173×91 | Dark Grey | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date; design similar to 20 złotych of 1936 (peasant's picture added in the margin) | See 20 złotych of 1936 | ||

| |

|

|

|

50 złotych | 180×100 | Dark green | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date; peasant, a statue and portrait of Emilia Plater | Sukiennice, Kraków | 1 March 1940, 1 August 1941 | |

| |

|

| |

|

100 złotych | 190×106 | Brown | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date; peasant | Bank of Poland building in Warsaw | 1 March 1940 | |

| |

|

| |

|

100 złotych | 187×98 | Grey through brown to red | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date | Lwów panorama | 1 August 1941 | |

| |

|

| |

|

500 złotych(also called "góral") | 181×100 | Olive | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date; góral | Denomination and the Morskie Oko lake in Tatra Mountains | 1 March 1940 | |

|

|

1000 złotych

(reconstruction) |

196×103 | Brown | Denomination, "Bank Emisyjny w Polsce" inscription, date; the head of "krakowiak"(not all banknotes) | Wawel Castle, Kraków | 1 August 1941(not released, only clichés left | |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||

Communist Poland (1945-1950)

The advance of the Red Army meant the transition to socialism, Poland being no exception.

The first monetary reform of post-war Poland was conducted in 1944, when the initial series of banknotes of communist Poland was released. This was essential for the recreation of the country, so the Polish Committee of National Liberation signed an act on 24 August 1944 introducing the banknotes. The older General Government banknotes were exchanged at par with the new ones. There were limits, however – 500 złotych only for an individual and 2000 złotych for the private enterprises and small manufacturers. The rest came onto the blocked bank accounts.

The banknotes had a very simple design, with no people or buildings featured. They carrieed the name of the as yet unformed Narodowy Bank Polski (the National Bank of Poland). Printing completed at the Goznak mint in Moscow. All the new banknotes of the series I (except for the 50 groszy, and 1000 złotych, which were only released later) had a faulty inscription, containing a russianism.

On 15 January 1945 the National Bank of Poland was finally created. Its first monetary action was the printing of 1000 złotych banknote in the newly built Polska Wytwórnia Papierów Wartościowych in Łódź. The first Communist series' banknotes were easy to counterfeit, so additional replacement banknotes were printed in 1946–48. As 500 złotych banknote was very easy to counterfeit, it was fully withdrawn in 1946.

The new (II and III) series were created from the graphic designs of Ryszard Kleczewski and Wacław Borowski.

| Obverse | Reverse | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Date of issue | Date of release | Amount

printed |

Date of withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

50 groszy | 81×52 | Bright pink | Denomination

"The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms |

Denomination | 1944 | 28 February 1945 | 6,706,000

(3,503,000 zł) |

8 November 1950 |

|

|

1 złoty | 136×66 | Green | Denomination,

"The National Bank of Poland" inscription |

18 September 1944 | 47,726,000 (47,726,000 zł) | |||

|

|

2 złote | 137×67 | Red | 18,725,000

(37,450,000 zł) | |||||

|

|

5 złotych | 142×71 | Brown | 81,183,000

(405,915,000 zł) | |||||

|

|

10 złotych | 160×80 | Blue | 27 August 1944 | 22,005,000

(220,050,000 zł) | ||||

|

|

20 złotych | 170×83 | Teal | 114,687,000

(2,293,740,000 zł) | |||||

|

|

50 złotych | 180×93 | Blue-violet | 26,342,000

(1,317,100,000 zł) | |||||

|

|

100 złotych | 188×100 | Pink | 71,237,000

(7,123,700,000 zł) | |||||

|

|

500 złotych | 193×102 | Olive | 19,787,000

(9,893,500,000 zł) |

17 December 1946 | ||||

|

|

1000 złotych

(by Ryszard Kleczewski) |

182×97 | Brown | 1945 | 1 September 1945 | ca. 19,000,000

(19,000,000,000 zł) |

8 November 1950 | ||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | ||||||||||

| Pictures | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Date of print | Date of release | Date of withdrawal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1 złoty | 98×54 | Red | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date | Denomination | 15 May 1946 | 2 December 1946 | 8 November 1950 |

|

|

2 złote | 104×57 | Green | 15 March 1947 | ||||

|

5 złotych | 122×66 | Grey-blue | 5 February 1948 | |||||

| File:10 zł 1946.jpg | File:10zł1946rev.jpg | 10 złotych | 128×70 | Brown, red | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription | 18 August 1947 | ||

| File:20zł 1946 av.jpg | File:20zł1946 rev.jpg | 20 złotych | 158×84 | Blue to red | Two planes; denomination | 1 July 1948 | |||

| File:50 zł 1946 av.jpg | File:50zł rev 1946.jpg | 50 złotych | 164×87 | Brown, violet | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a steam boat and a sail boat | Boats on the sea, anchors; denomination | 22 September 1947 | ||

|

100 złotych | 170×91 | Red, brown | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a female peasant with a bunch of cereals, a male peasant with a bunch of wheat and a sickle | A peasant on a tractor in the field | 2 December 1946 | |||

|

|

500 złotych | 176×94 | Green to blue | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a sailor with an anchor and a model of ship; a fisherman | The Old City in Gdańsk | 15 January 1946 | 15 July 1946 | |

|

|

1000 złotych | 182×97 | Brown | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; miners | Łódź factories panorama | ? | ||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||

| Pictures | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Date of print | Date of release | Date of withdrawal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:20zł 1947 av.jpg | File:20zł1947rev.jpg | 20 złotych | 158×84 | Dark green | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms | A globe, a book, a machinery detail, a hammer and ralis, symbolising education and industrial work | 15 July 1947 | 16 June 1949 | 8 November 1950 |

| File:100 zł 1947 av.jpg | File:100 zł 1947 rev.jpg | 100 złotych | 170×91 | Brown-red | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a female peasant | Horses in a field | 21 February 1949 | ||

| File:500 zł 1947 av.jpg | File:500 zł 1947 rev.jpg | 500 złotych | 176×94 | Blue | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a female sailor with an anchor | Gdynia port | 1 July 1947 | 20 January 1949 | |

| File:1000 zł 1947 av.jpg | File:1000 zł 1947 rev.jpg | 1000 złotych | 182×97 | Olive, brown | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms; a miner with a hammer | A picture of a factory | 1 December 1948 | ||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||

The IV series banknotes had a longer life. Mainly due to their underdeveloped security features, the first three series were taken out of circulation in line with legislation signed on 28 October 1950, covering the introduction of the new Polish złoty (PLZ). Older banknotes had to be exchanged within 8 days for the new series IV, which had been designed, printed and distributed in great secrecy.

About in the same time, new coins were introduced, which circulated for more than four decades.

Third złoty

| Pictures | Denomination | Size(mm) | Colour | Obverse | Reverse | Date of print | Date of release | Date of withdrawal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:2 zł 1948 av.jpg | File:2 zł 1948 rev.jpg | 2 złote | 120×58 | Pale green | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown) | Buildings | 1 July 1948 | 30 October 1950 | 30 September 1960 |

| File:5 zł 1948 av.jpg | File:5 zł 1948 rev.jpg | 5 złotych | 142×67 | Brown | A peasant on a tractor in a field | 31 December 1959 | |||

| File:10zł 1948 av.jpg | File:10zł 1948 rev.jpg | 10 złotych | 148×70 | Olive-brown | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); portrait of a peasant | Peasants at harvesting cereals | 31 December 1965 | ||

| File:20zł 1948 av.jpg | File:20zł1948rev.jpg | 20 złotych | 160×76 | Blue | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); portrait of a woman | Cloth Hall, Kraków | 30 June 1977 | ||

| File:50 zł 1948 av.jpg | File:50zł rev 1948.jpg | 50 złotych | 164×78 | Green to olive | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); portrait of a fisherman | Gdynia port | 30 June 1978 | ||

| File:100zł 1948 av.jpg | File:100 zł 1948 rev.jpg | 100 złotych | 172×82 | Red | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); portrait of a miner | A picture of a factory | 30 June 1977 | ||

| File:500 zł 1948 av.jpg | File:500 zł 1948 rev.jpg | 500 złotych | 178×85 | Black-brown | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); portrait of a miner | A picture of coal mining | 31 December 1977 | ||

| File:1000 zł 1965 av.jpg | File:1000 zł 1965 rev.jpg | 1000 złotych | 150×74 | Bright yellow, red, brown and grey | Denomination, "The National Bank of Poland" inscription, date, coat of arms (without the crown); Mikołaj Kopernik | Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric model of the Solar System | 29 October 1965 | 1 June 1966 | 31 December 1978 |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||

In 1950, a new złoty (PLZ) was introduced, replacing all notes issued up to 1948 at a rate of one hundred to one, while all bank assets were redenominated in the ratio 100:3. The new banknotes were dated 1948, while the new coins 1949. Initially, by law with effect from from 1950 1 złoty (zł) was made equal to 0.222168g of pure gold (Dziennik Ustaw 50, 459).

As in all the Warsaw Bloc countries, Poland started nationalising major industrial and manufacturing businesses. The necessary legislative act was signed in 1946. However, smaller enterprises remained in private hands, in contrast to the USSR. Despite this concession, the whole economy was under firm state control. In the agricultural sector, farmers (still the major generation source of Polish income) received additional lands from the government. These properties were the result of confiscations from the church, wealthy families as well from farmers who would no abide by the changed policies.

In the late 1940s, Polish currency became unstable. This was largely due to internal opposition to the new regime and made an already difficult economic situation no better. Eventually things changed and the złoty became stronger in 1948-9.

Beginning in 1950, the state started implementing the collectivisation policy on a mass scale. Some farmers were grouped into newly created PGRs (State Agricultural Farms). Others supplied produce to the state for distribution and had to comply with obligatory centralised food deliveries (first of cereals, in 1951; and from 1952 on, of meat, potatoes and milk). Privately owned and ndividually-run farms were bunkrupted, as the state bought at extremely low prices, much lower than market value.

Agriculture might have been ruined in a few years if not for the death of President and latterly Secretary General of the Central Committee of the PUWP Bolesław Bierut under mysterious circumstances in 1956. The new government under Władysław Gomułka began relaxing the earlier years' hardcore Stalinist policies. State Farms were reformed, enforged obligatory deliveries reduced and state buying prices were raised. On the whole the structure was little different from that of 1949: industry was state-owned, while agriculture was mostly in private hands.

Serious reforms were proposed in early 1970s by Edward Gierek, which aimed to improve the situation for normal people. Unfortunately, the government had inadequate funds to initiate these reforms. This explains Poland's growing financial indebtedness to the USSR and other Warsaw Bloc countries, promoting the view that "the investments will upgrade the Poland's potential, which will be aimed at export, so that the country will pay the interest and at the same time maintain a high industrial production". In fact, although the intention was to create employment, it never happened. Poland's debt burden grew too large, forming the main cause of further financial crisis. After a period of prosperity in 1971-8, Poland entered into a very deep recession, which worsened over time as Poland was unable to meet devt interest obligations. The crisis was to last until 1994. The first indications of the crisis was obvious by the mid-70s, when there began a period of rampant inflation. Złoty devaluation continued. In 1980 Gierek's government was accused of corruption. He was removed from the Presidency in 1980.

Financial crisis of 1980s

The first big strikes started in Gdańsk and GOP (Upper Silesian Industrial Area). These restricted industrial production which by then had become the main economical sector. The situation was worsened by the previous period of prosperity in the early and mid 70s, which had promoted increased demand and consumption. The government was forced either to lower salaries and wages or to make workers redundant. This accelerated the crisis. Moreover, the demand was more diminished, as the government provided food rationing. The martial law of 1981–83 deepened the crisis.

By the early 80s inflation in Poland becoming out of control – over 100% per annum in 1982. It was reduced in the mid-80s to about 15% per annum, but again started in late-80s. Economic conditions did not allow any salary and pension increases because of the huge debt burden, which doubled in the 1980s. By 1981 it was admitted that the situation was beyond management. In an effort to escape such situation, Poland started massively printing banknotes, without any covering from bank resources. Banknotes denominated at 5,000 złotych were introduced in 1982, 10,000 złotych in 1988, 20,000 and 50,000 złotych in 1989, and 100,000, 200,000 and 500,000 złotych in 1990. Grosz coins were rendered worthless and coins were mostly made out of aluminium (with the exception of the commemorative ones).

Given the circumstances, the only solution appeared to be the liberisation of the economy. In 1988 Mieczysław Rakowski was forced to accept the possibility of transition of the state enterprises into private hands. In fact, as stated earlier, smaller enterprises were private, and 18% of GDP was made by private sector, additional 10% – by the cooperatives. These were not, however, the Perestroika cooperatives, but ones with limited experience in the market economy. These were ready to transfer to a market economy. The Communist authorities had to admit they had no grip on the economy, which was another reason to introduce changes.

Leszek Balcerowicz was behind the idea of shifting the economic basis from state-based to free-trade. To achieve this, the following were introduced:

- Liberalisation of prices. This caused very high inflation in Poland (585.5% per annum in 1990 alone);

- The state gave free access to all areas of economic enterprise (January 1989 - January 1990);

- Fresh budget cuts on the state-owned enterprises and lowering the tempo of inflation to more normal levels

- New financing and credit policies as well as the attraction of direct investments;

- Measures to increase the convertibility of the national currency in all operations;

- Liquidation of foreign trade controls (1990).

The worst years of the crisis began in 1988, when the level of inflation rose higher than 60% per annum. Inflation peaked in 1990, characterised as hyperinflation, as the monthly rate was higher than 50%. However by December 1991 it decreased below 60% per annum, and by 1993 it firmly established below 40%, which was an acceptable inflation rate for the economy. As a result, the złoty regained the confidence of foreign investors. The remaining issue was the redenomination of the depreciated złoty.

Polish złoty coins (PLZ)

| Pictures | Denomination | Ø | Mass | Metal | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Issued in Budapest | Issued in Warsaw | Issued in Basel | Issued in Kremnica | Issued in Leningrad | Introduced | Issued | Withdrawn | With inscription "... Ludowa"? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:1 gr 1949.jpg | 1 grosz | 14.7 | 0.5 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, leaf ornament | 400,000,000 | 116,000 | 1954 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | |||

| File:Poland-2-grosze-1949-av.jpgFile:Poland-2-grosze-1949-rev.jpg | 2 grosze1 | 16 | 0.57 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, leaf ornament | 1954 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | |||||

| File:5-groszy-1949-rok-brąz.jpg | 5 groszy | 20 | 3 | bronze | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, leaf ornament | 300,000,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1956 | No | ||||

| File:5 gr 1949 av.jpgFile:Poland-2-grosze-1949-rev.jpg | 5 groszy | 20 | 1 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, leaf ornament | 200,000,000 | 1960 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:5 gr 1958 av.jpg | 5 groszy | 16 | 0.6 | aluminium | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, leaf ornament | 310,364,378 | 1958 | 1958-63; 1965; 1967-8; 1970-2 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 gr 1949 cuni.jpg | 10 groszy | 17.6 | 2 | cupronickel | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 200,000,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:10 gr 1949 al.jpg | 10 groszy | 17.6 | 0,7 | aluminium | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 31,046,685 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:10-gr-1963 al.jpg | 10 groszy | 17.6 | 0,7 | aluminium | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 1,179,713,719 | 100,000,000 | 1961 | 1961-3; 1965–81; 1983; 1985 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:10 gr 1949 cuni.jpg | 10 groszy | 20 | 3 | cupronickel | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 133,383,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:20 gr 1949 av.jpgFile:20 gr 1949 rev.jpg | 20 groszy | 20 | 1 | aluminium | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 197,491,750 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:20 gr 1949 av.jpgFile:20 gr 1957 rev.jpg | 20 groszy | 20 | 1 | aluminium | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 879,964,867 | 50,000,000 | 1957 | 1957; 1961-3; 1965–73; 1975-8; 1980-1; 1983; 1985 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:50 gr 1949 cuni.jpg | 50 groszy | 23 | 5 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 109,000,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:50 gr 1949 al.jpg | 50 groszy | 23 | 1.6 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 59,392,950 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:50 gr 1956 al.jpg | 50 groszy | 23 | 1.6 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 376,793,589 | 66,800,000 | 1957 | 1957; 1965; 1967-8; 1970–78; 1982–85 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:50groszyprl1986.png | 50 groszy | 23 | 1.6 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 49,052,000 | 1986 | 1986-7 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:Poland-1-Złoty-1949-cuni.jpg | 1 złoty | 25 | 7 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 87,053,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:Poland-1-Złoty-1949-al.jpg | 1 złoty | 25 | 2.12 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 43,000,000 | 1950 | 1949 | 1 January 1995 | No | ||||

| File:1 zł 1967 coin av.jpgFile:1 zł 1967 coin rev.jpg | 1 złoty | 25 | 2.12 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 1,110,555,639 | 60,000,106 | 1957 | 1957, 1965–78, 1980–88 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:1 zł 1990 coin.jpg | 1 złoty | 16 | 0.57 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 1989 | 1989-90 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||||

| File:2 zł 1958 coin.jpg | 2 złote | 27 | 2.7 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch and cereal ornament | 189,955,432 | 1958 | 1958-60; 1970–74 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:2 zł 1975 coin av.jpgFile:2 zł 1975 coin rev.jpg | 2 złote | 21 | 3 | brass | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch and cereal ornament | 633,950,957 | 137,600,000 | 1975 | 1975-1988 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:2 zł 1989 coin av.jpgFile:2 zł 1989 coin rev.jpg | 2 złote | 18 | 0.7 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch and cereal ornament | 132,217,000 | 1989 | 1989-90 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:5 zł fisherman 1958.jpg | 5 złotych | 29 | 3.45 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, fisher | 126,439,614 | 1958 | 1958-60; 1971; 1973-4 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:5 zł 1984 brass.jpg | 5 złotych | 24 | 5 | brass | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 315,831,723 | 135,000,000 | 1975 | 1975-88 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:5 zł 1990 al.jpg | 5 złotych | 20 | 0.88 | aluminium | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 68,501,000 | 1989 | 1989-90 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł Kopernik 1959 cuni.jpg | 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; Nicolaus Copernicus | 15,558,855 | 1959 | 1959; 1965 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł Kopernik rewers cuni.jpgFile:10 zł Mikołaj Kopernik averse cuni norm.jpg | 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; Nicolaus Copernicus | 20,129,000 | 1967 | 1967-9 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| Analogical to the one lower | 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; Tadeusz Kościuszko | 44,808,153 | 1959 | 1959-60; 1966 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł Tadeusz Kościuszko coin.jpg | 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; Tadeusz Kościuszko | 45,111,000 | 1969 | 1969-73 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł bolesław prus 1977.jpg | 10 złotych | 25 | 7.7 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, Bolesław Prus | 136,314,606 | 1975 | 1975-8;

1981-4 |

1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł Bolesław Prus av.jpgFile:10 zł Bolesław Prus rev.jpg | 10 złotych | 25 | 7.7 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, | >55,000,000 | 1975 | 1975-7 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł 1984 cuni.jpg | 10 złotych | 25 | 7.7 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 224,209,255 | 1984 | 1984-8 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:10 zł 1984 mnbrass.jpg | 10 złotych | 22 | 4.27 | manganese brass | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 187,692,000 | 1989 | 1989-90 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:20 zł coin 1973 skyscraper.jpg | 20 złotych | 29 | 10.15 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; a skyscraper and cereals | 20,000,000 | 37,000,000 | 1973 | 1973-4; 1976 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:20 zł Marceli Nowotko coin.jpg | 20 złotych | 29 | 10.15 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination; Marceli Nowotko | 56,152,000 | 30,000,000 | 1974 | 1974-7; 1983 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | |||

| File:20 zł simple 1984.jpg | 20 złotych | 26.5 | 8.7 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 103,383,710 | 1984 | 1984-8 | 1 January 1995 | Yes | ||||

| File:20 zł simple 1989.jpg | 20 złotych | 24 | 5.65 | cupronickel | rifled | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination | 200,686,000 | 1989 | 1989-90 | 1 January 1995 | Yes |

In 1949, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 groszy and 1 złoty coins were issued. The first two denominations were minted only in 1949, the rest also later.

In 1952, Poland's official name was changed from "Republic of Poland" to "People's Republic of Poland". Coins minted in 1949 featured the former name. The 5 groszy brass coin was withdrawn in 1956. The rest circulated until 1994.

The 2, 5 and 10 złotych banknotes were withdrawn in 1960s to be exchanged for coins.

The coins from 1 grosz to 2 złote were quite simple designs but the 5, 10 and 20 złotych coins featured people (5 złotych had a fisherman, 10 złotych had Copernicus, Mickiewicz with Prus on its obverse, and 20 złotych, most notably, Marceli Nowotko), until the 1980s. As the Polish złoty became cheaper over time, older coins were rendered worthless (however, they stayed in circulation), and the simple new coins were released only in złote denominations. All the PRP and 1990 issued coins were withdrawn in 1994, as a result of the monetary reform conducted at that time.

| Pictures | Denomination | Diameter | Mass | Metal | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Amount minted | Introduced | Issued | Withdrawn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File:50 zł hyperinflatory 1990.jpg | 50 złotych | 26 | 6.8 | cupronickel | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 28,707,000 | 1990 | 1990 | 1 January 1995 |

| File:100 zł hyperinflatory 1990.jpg | 100 złotych | 28.6 | 7.68 | cupronickel | smooth | Coat of arms, year of minting | Denomination, branch ornament | 37,341,000 | 1990 | 1990 | 1 January 1995 |

| Pictures | Value | Diameter(mm) | Mass(g) | Metal | Obverse | Reverse | Amount minted | Issued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | Casimir III the Great, "Six hundred years of Jagiellonian University"(in Polish). Inscriptions concave | 2,610,100 | 1964 | |

| 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | Casimir III the Great, "Six hundred years of Jagiellonian University"(in Polish). Inscriptions convex | 2,611,539 | 1964 | |

| 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | "Seven centuries of Warsaw" in Polish; figure of Nike | 3,492,000 | 1965 | |

| 10 złotych | 31 | 12.9 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa" | "Seven centuries of Warsaw" in Polish; Sigismund's Column; denomination | 2 mln | 1965 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa" | "Seven centuries of Warsaw" in Polish; Sigismund's Column; denomination | 102,000 | 1966 | |

| 100 złotych | 35 | 20 | silver(90% alloy) | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; coat of arms of the voivoderships of the Rzeczpospolita | Mieszko I and Doubravka of Bohemia; denomination; "Tysiąclecie państwa polskiego"(thousand years of Poland) | 198,000 | 1966 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | General Karol Świerczewski | 2,000,000 | 1967 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa" | Marie Curie; denomination | 2,000,000 | 1967 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; "orzeł strzelecki" | "XXV years of People's Army of Poland"(in Polish); head of a soldier, denomination | 2,000,000 | 1968 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa" | "Dwudziesta piąta rocznica PRL"(Twenty-five years of PPR); cereals, years of communist rule | 2,000,000 | 1969 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms(with another one on the shield inside the bigger one), year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | "Byliśmy - Jesteśmy - Będziemy"("We were, we are, we will be"), date(1945-1970); some coat of arms; a pillar with "PRL" written and its coat of arms | 2,000,000 | 1970 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms(in a shield), year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | FAO; wheat and fish on a coin | 2,000,000 | 1971 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | "50 years of the III Silesian Uprising"; Virtuti Militari cross | 2,000,000 | 1971 | |

| 10 złotych | 28 | 9.5 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination, borders of Poland. Writings go along the borders. | "50 years of Gdynia port" | 2,000,000 | 1972 | |

| 50 złotych | 30 | 12.75 | silver(75% alloy) | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | Fryderyk Chopin | 49,999(1972)

10,375(1974) |

1972

1974 | |

| 100 złotych | 32 | 16.5 | silver(62.5% alloy) | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | Mikołaj Kopernik | 51,048(1973)

50,000(1974) |

1973

1974 | |

| 20 złotych | 29 | 10.15 | cupronickel | Coat of arms, year of minting; inscription: "Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa"; denomination | "XXV years of Comecon" | 2,000,000 | 1974 | |