Pope Adrian VI

Pope Adrian VI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Papacy began | 9 January 1522 |

| Papacy ended | 14 September 1523 |

| Predecessor | Leo X |

| Successor | Clement VII |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 30 June 1490 |

| Consecration | August 1516 by Diego Ribera de Toledo |

| Created cardinal | 1 July 1517 by Pope Leo X |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Adriaan Floriszoon Boeyens 2 March 1459 |

| Died | 14 September 1523 (aged 64) Rome, Papal States |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Motto | Patere et sustine ("Respect and wait") |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Adrian | |

| Papal styles of Pope Adrian VI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Pope Adrian VI (Template:Lang-la), born Adriaan Florensz (Boeyens)[1] (2 March 1459 ‒ 14 September 1523), was Pope of the Catholic Church from 9 January 1522 until his death on 14 September 1523. He was the only Dutchman ever to be Pope.

Pope Adrian VI was born in the Prince-Bishopric of Utrecht in the Netherlands and was the last non-Italian pope until Pope John Paul II from Poland became pope in 1978. Pope Adrian VI and his eventual successor Pope Marcellus II are the only popes of the modern era to retain their baptismal names after their election.

Early life

Adriaan Florensz was born on 2 March 1459 in the city of Utrecht, which was then the capital of the Prince-Bishopric of Utrecht,[2] a part of the Burgundian Netherlands in the Holy Roman Empire. He was born into modest circumstances as the son of Florens Boeyensz, also born in Utrecht, and his wife Geertruid. He had three older brothers, Jan, Cornelius, and Claes.[3] Adrian consistently signed with Adrianus Florentii or Adrianus de Traiecto ("Adrian of Utrecht") in later life, suggesting that his family did not yet have a surname but used patronymics only.[4]

Adrian was probably raised in a house on the corner of the Brandsteeg and Oude Gracht that was owned by his grandfather Boudewijn (Boeyen, for short). His father, a carpenter and likely shipwright, died when Adrian was 10 years or younger.[5] Adrian studied from a very young age under the Brethren of the Common Life, either at Zwolle or Deventer and was also a student of the Latin school (now Gymnasium Celeanum) in Zwolle.[6]

Leuven

In June 1476, he started his studies at the University of Leuven,[7] where he pursued philosophy, theology and Canon Law, thanks to a scholarship granted by Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy. In 1478 he had the title of Primus Philosophiae, as well as that of Magister Artium (that is, he took his undergraduate degree). In 1488 he was chosen by the Faculty of Arts to be their representative on the Council of the University.[8]

On 30 June 1490, Adrian was ordained a priest.[9]

After the regular 12 years of study, Adrian became a Doctor of Theology in 1491. He had been a teacher at the University since 1490, was chosen vice-chancellor of the university in 1493, and Dean of St. Peter's in 1498. In the latter function he was permanent vice-chancellor of the University and de facto in charge of hiring. His lectures were published, as recreated from his students' notes; among those who attended was the young Erasmus. Adrian offered him a professorate in 1502, but Erasmus refused.[4]

In November 1506 Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy became Governess of the Habsburg Netherlands and chose Adrian as her advisor. The next year Emperor Maximilian I appointed him also tutor to his seven-year-old grandson, and Margaret's nephew, Charles, who in 1519 would become Emperor Charles V. By 1512 Adrian was Charles's advisor and his court obligations were so time consuming that he quit his positions at the university.[4]

Spain

In 1515, Charles sent Adrian to Spain to convince his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand II of Aragon, that the Spanish lands should come under his rule, and not Charles's Spanish-born younger brother Ferdinand, whom his grandfather had in mind. Adrian succeeded in that just before Ferdinand's death in January 1516.[4] Ferdinand of Aragon,[10] and subsequently Charles V, appointed Adrian Bishop of Tortosa, which was approved by Pope Leo X on 18 August 1516.[11] He was consecrated by Bishop Diego Ribera de Toledo.

On 14 November 1516 the King commissioned him Inquisitor General of Aragon.

In his fifth Consistory for the creation of cardinals, on 1 July 1517, Pope Leo X (1513–21) named thirty-one cardinals among whom was Adrianus de Traiecto,[2] naming him Cardinal Priest of the Basilica of Saints John and Paul on the Coelian Hill.[12]

During the minority of Charles V, Adrian was named to serve with Cardinal Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros as co-regent of Spain. After the death of Jimenez, Adrian was appointed (14 March 1518) General of the Reunited Inquisitions of Castile and Aragon, in which capacity he acted until his departure for Rome.[13] When Charles V left Spain for the Netherlands in 1520, he appointed Cardinal Adrian Regent of Spain, during which time he had to deal with the Revolt of the Comuneros.

Papal election

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

In the conclave after the death of the Medici Pope Leo X, Leo's cousin, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, was the leading figure. With Spanish and French cardinals in a deadlock, the absent Adrian was proposed as a compromise and on 9 January 1522 he was elected by an almost unanimous vote. Charles V was delighted upon hearing that his tutor had been elected to the papacy but soon realised that Adrian VI was determined to reign impartially. Francis I of France, who feared that Adrian would become a tool of the Emperor, and had uttered threats of a schism, later relented and sent an embassy to present his homage.

Fears of a Spanish Avignon based on the strength of his relationship with the Emperor as his former tutor and regent proved baseless, and Adrian, having notified the College of Cardinals of his acceptance,[14] left for Italy after six months of preparations and trying to decide which route to take, making his solemn entry into Rome on 29 August. He had forbidden elaborate decorations, and many people stayed away for fear of the plague that was raging. Pope Adrian was crowned at St. Peter's Basilica on 31 August 1522, at the age of 63.

Reformer

He immediately entered upon the path of the reformer. The 1908 edition of the Catholic Encyclopedia characterised the task that faced him:

- "To extirpate inveterate abuses; to reform a court which thrived on corruption, and detested the very name of reform; to hold in leash young and warlike princes, ready to bound at each other's throats; to stem the rising torrent of revolt in Germany; to save Christendom from the Turks, who from Belgrade now threatened Hungary, and if Rhodes fell would be masters of the Mediterranean - these were herculean labours for one who was in his sixty-third year, had never seen Italy, and was sure to be despised by the Romans as a 'barbarian'.[2]

His plan was to attack notorious abuses one by one; however, in his attempt to improve the system of indulgences he was hampered by his cardinals. He found reduction of the number of matrimonial dispensations to be impossible, as the income had been farmed out for years in advance by Pope Leo X.[13]

Papacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Adrian VI was not successful as a peacemaker among Christian princes, whom he hoped to unite in a war against the Turks. In August 1523 he was forced into an alliance with the Empire, England, and Venice against France; meanwhile, in 1522 the Sultan Suleiman I (1520–66) had conquered Rhodes.

In his reaction to the early stages of the Lutheran revolt, Adrian VI did not completely understand the gravity of the situation. At the Diet of Nuremberg, which opened in December 1522, he was represented by Francesco Chiericati, whose private instructions contain the frank admission that the disorder of the Church was perhaps the fault of the Roman Curia itself, and that it should be reformed.[15][16] However, the former professor and Inquisitor General was strongly opposed to any change in doctrine and demanded that Luther be punished for teaching heresy.[13]

He made only one cardinal in the course of his pontificate, Willem van Enckevoirt, made a cardinal priest in a consistory held on September 10, 1523.

Adrian VI held no beatifications in his pontificate but canonized Saints Antoninus of Florence and Benno of Meissen on 31 May 1523.

Charles V's ambassador in Rome, Juan Manuel, lord of Belmonte, wrote that he was worried that Charles's influence over Adrian waned after Adrian's election, writing " The Pope is "deadly" afraid of the College of Cardinals. He does whatever two or three cardinals write to him in the name of the college."[17]

Death

Adrian VI died in Rome on 14 September 1523, after one year, eight months and six days as pope. Most of his official papers were lost after his death. He published Quaestiones in quartum sententiarum praesertim circa sacramenta (Paris, 1512, 1516, 1518, 1537; Rome, 1522), and Quaestiones quodlibeticae XII. (1st ed., Leuven, 1515). He is buried in the Santa Maria dell'Anima church in Rome.

He bequeathed property in the Low Countries for the foundation of a college at the University of Leuven that became known as Pope's College.

The pope was mocked by the people of Rome on the Pasquino, and the Romans, who had never taken a liking to a man they saw as a "barbarian", rejoiced at his death.

Pope Adrian VI in popular culture

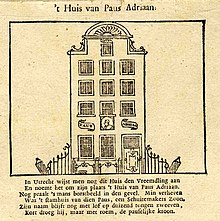

The first series of engravings used to educate Dutch school children at the turn of the 18th century includes Adrian VI in its woodcut on 'Famous Dutch Men and Women' with the following poem:

- In Utrecht wijst men nog dit huis den vreemdeling aan,

- En noemt het om zijn naam 't huis van Paus Adriaan,

- Nog praalt 's mans borstbeeld in den gevel. Min verheven

- Was 't het stamhuis van dien Paus, een schuitemakers zoon,

- Zijn naam blijft nog vol lof op duizend tongen zweeven,

- Kort droeg hij, maar met roem, de pauselijke kroon.'

- In Utrecht they still show the stranger this house,

- And calls it the house of pope Adrian,

- Still his bust stands in its façade, only slightly elevated,

- It was the birth house of this pope, the son of a boat builder,

- His name is still proudly spoken by thousands of tongues,

- Short of time, but with honor, he wore the papal crown.

Pope Adrian VI was a character in Christopher Marlowe's theatre play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (published 1604).

Italian writer Luigi Malerba used the confusion among the leaders of the Catholic Church, which was created by Adrian's unexpected election, as a backdrop for his 1995 novel, Le maschere (The Masks), about the struggle between two Roman cardinals for a well-endowed church office.

In an episode of the American TV show Law & Order entitled Divorce, a homeless man believes he is Pope Adrian VI.[18]

Bibliography

- Luther, Martin. Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters, 2 vols., tr.and ed. by Preserved Smith, Charles Michael Jacobs, The Lutheran Publication Society, Philadelphia, Pa. 1913, 1918. vol.I (1507–1521) and vol.2 (1521–1530) from Google Books. Reprint of Vol.1, Wipf & Stock Publishers (March 2006). ISBN 1-59752-601-0

- Gross, Ernie. This Day In Religion. New York:Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc, 1990. ISBN 1-55570-045-4.

- Malerba, Luigi. Le maschere, Milan: A. Mondadori, 1995. ISBN 88-04-39366-1

- Verweij, Michiel. Adrianus VI (1459-1523): de tragische paus uit de Nederlanden, Antwerpen & Apeldoorn: Garant Publishers, 2011. ISBN 90-44-12664-4

- Höfler, Karl Adolf Constantin, Ritter von (1880). Papst Adrian VI. 1522-1523 (in German: Fraktur). Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Domarus, M. v. "Die Quellen zur Geschichte des Papstes Hadrian VI.," Historisches Jahrbuch 16 (München 1895), 70-91.

- Giovio, Paolo (1551). Vita Leonis Decimi, pontifici maximi: libri IV...Hadriani VI... et Pompeii Columnae... (in Latin). Florence: Lorenzo Torrentini.

- Paulus Jovius, "Vita Hadriani VI," in Gaspar Burmann, Analecta historica de Hadriano Sexto (Utrecht 1727) 85-150.

- Creighton, Mandell. A History of The Papacy during the Period of the Reformation Volume V (London 1894).

- Creighton, Mandell (1897). A History of the Papacy from the Great Schism to the Sack of Rome. Vol. Volume VI. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Gregorovius, Ferdinand. The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (translated from the fourth German edition by A. Hamilton) Volume 8 part 2 [Book XIV, Chapter 4-5] (London 1902)

- Pastor, Ludwig. History of the Popes (tr. R.F. Kerr) Volume VIII (St. Louis 1908).

- Pasolini, Guido. Adriano VI. Saggio Storico (Rome, 1913).

- Gulik, Guilelmus van; Konrad Eubel (1923). L. Schmitz-Kallenberg (ed.). Hierarchia catholica medii aevi (in Latin). Vol. Volume III (editio altera ed.). Münster: sumptibus et typis librariae Regensbergianae.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Rodocanachi, E. (1931). "La jeunesse d' Adrien VI". Revue historique. 56: 300–307. JSTOR 40944759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - McNally, Robert E. (1969). "Pope Adrian VI (1522-23) and Church Reform". Archivum Historiae Pontificiae. 7: 253–285. JSTOR 23563708.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Peter G. Bietenholz; Thomas Brian Deutscher (6 September 2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 5–9. ISBN 978-0-8020-8577-1.

- Stone, M.W.F (2006). "Adrian of Utrecht and the University of Louvain: Theology and the Discussion of Moral Problems in the late Fifteenth Century". Traditio. 61: 247–287. JSTOR 27832061.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)

See also

- Coster, Wim (2003), Metamorfoses. Een geschiedenis van het Gymnasium Celeanum, Zwolle: Waanders, ISBN 90-400-8847-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|chapterurl=(help) - Creighton, Mandell (1919), A History of the Papacy from the Great Schism to the Sack of Rome, vol. 6, New York: Longmans, Green

- Duke, Alastair (2009), "The Elusive Netherlands: The Question of National Identity in the Early Modern Low Countries on the Eve of the Revolt", in Duke, Alastair; Pollmann,, Judith; Spicer, Andrew (eds.), Dissident identities in the early modern Low Countries, Farnham: Ashgate Publishers, pp. 9–57, ISBN 978-0-7546-5679-1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2007), Fundamentalism, New York: Infobase Publishing, ISBN 0-8160-6767-8

- Howell, Robert B. (2000), "The Low Countries: A Study in Sharply Contrasting Nationalisms", in Barbour, Stephen; Carmichael, Cathie (eds.), Language and nationalism in Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 130–50, ISBN 0-19-823671-9

- Schlabach, Gerald W. (2010), Unlearning Protestantism: Sustaining Christian Community in an Unstable Age, Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, ISBN 978-1-58743-111-1

Notes

- ^ Dedel, according to Collier's Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Rodocanachi, p. 301.

- ^ a b c d Jos Martens, Bio and review of Verweij book at Histoforum Magazine.

- ^ Gerard Weel Life and times of Adrian of Utrecht (in Dutch)

- ^ Coster. "De Latijnse School te Zwolle". Metamorfoses. pp. 17, 19. Rodocanachi, p. 301-302.

- ^ The date was 1 June 1476 according to the Matriculation Register: Rodocanachi, p. 302 and n. 1.

- ^ Rodocanachi, p. 302.

- ^ David Cheney, Catholic-Hierarchy: Adrian Florenszoom Dedel. Retrieved: 2016-05-14.

- ^ Paolo Giovio, Vita Hadriani VI, p. 119.

- ^ Gulik and Eubel, p. 186.

- ^ Gulik and Eubel, pp. 16 and 63.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Adrian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 216.

- ^ Adrian VI (1522). Copia Brevis S. D. N. Adriani VI. in summum Pontificem electi, ad sacrosanctum Cardinalium Collegium (in Latin). Caesaraugusta (Saragossa).

- ^ Pigafetta, Antonio and Theodore J. Cachey, The first voyage around the world, 1519–1522, (University of Toronto Press, 2007), 128.

- ^ Hans Joachim Hillerbrand, The division of Christendom: Christianity in the sixteenth century, (Westminster John Knox Press, 2007), 141.

- ^ British History Online. (15 April 1522 entry)

- ^ Dyess-Nugent, Phil, Law & Order: Slave to formula, or crackling entertainment?, The A. V. Club.