Special Relationship

The Special Relationship is a phrase used to describe the exceptionally close political, diplomatic, cultural, economic, military and historical relations between the United Kingdom and the United States following its use in a 1946 speech by British statesman Winston Churchill. Although both the United Kingdom and United States have close relationships with many other nations, the level of cooperation between them in economic activity, trade and commerce, military planning, execution of military operations, nuclear weapons technology, and intelligence sharing has been described as "unparalleled" among major powers.[1]

The United Kingdom and United States have been close allies in numerous military and political conflicts throughout the 20th and 21st centuries including World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, the Gulf War, and the War on Terror.

Churchillian emphasis

Although the special relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States was emphasised by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, its existence had been recognised since the 19th century, not least by rival powers.[2] Their troops had been fighting side by side—sometimes spontaneously—in skirmishes overseas since 1859, and the two democracies shared a common bond of sacrifice in World War I.

Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald's visit to the United States in 1930 confirmed his own belief in the "special relationship", and for this reason he looked to the Washington Treaty rather than a revival of the Anglo-Japanese alliance as the guarantee of peace in the Far East.[3] However, as David Reynolds observes: "For most of the period since 1919, Anglo-American relations had been cool and often suspicious. America's 'betrayal' of the League of Nations was only the first in a series of US actions—over war debts, naval rivalry, the 1931–2 Manchurian crisis and the Depression—that convinced British leaders that the United States could not be relied on".[4] Equally, as President Truman's secretary of state, Dean Acheson, recalled: "Of course a unique relation existed between Britain and America—our common language and history ensured that. But unique did not mean affectionate. We had fought England as an enemy as often as we had fought by her side as an ally".[5]

The fall of France in 1940 has been described as a decisive event in International relations, leading the special relationship to displace the entente cordiale as the pivot of the international system.[6] During World War II, one observer noted that "Great Britain and the United States integrated their military efforts to a degree unprecedented among major allies in the history of warfare".[7] "Each time I must choose between you and Roosevelt", Churchill shouted at General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French, in 1945, "I shall choose Roosevelt".[8] Between 1939 and 1945 Churchill and Roosevelt exchanged 1,700 letters and telegrams and met 11 times; Churchill estimated that they had 120 days of close personal contact.[9]

Churchill's mother was a U.S. citizen, and he keenly felt the links between the English-speaking peoples. He first used the term "special relationship" on 16 February 1944, when he said it was his "deepest conviction that unless Britain and the United States are joined in a special relationship… another destructive war will come to pass".[10] He used it again in 1945 to describe not the Anglo-American relationship alone, but the United Kingdom's relationship with both the United States and Canada.[11] The New York Times Herald quoted Churchill in November 1945:

We should not abandon our special relationship with the United States and Canada about the atomic bomb and we should aid the United States to guard this weapon as a sacred trust for the maintenance of peace.[11]

Churchill used the phrase again a year later, at the onset of the Cold War, this time to note the special relationship between the United States on the one hand, and the English-speaking nations of the British Commonwealth and Empire under the leadership of the United Kingdom on the other. The occasion was his 'Sinews of Peace Address' in Fulton, Missouri, on 5 March 1946:

Neither the sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organization will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples ...a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States. Fraternal association requires not only the growing friendship and mutual understanding between our two vast but kindred systems of society, but the continuance of the intimate relationship between our military advisers, leading to common study of potential dangers, the similarity of weapons and manuals of instructions, and to the interchange of officers and cadets at technical colleges. It should carry with it the continuance of the present facilities for mutual security by the joint use of all Naval and Air Force bases in the possession of either country all over the world.

There is however an important question we must ask ourselves. Would a special relationship between the United States and the British Commonwealth be inconsistent with our over-riding loyalties to the World Organisation? I reply that, on the contrary, it is probably the only means by which that organisation will achieve its full stature and strength.

In the opinion of one international relations specialist: "the United Kingdom's success in obtaining US commitment to cooperation in the postwar world was a major triumph, given the isolation of the interwar period".[12] A senior British diplomat in Moscow, Thomas Brimelow, admitted: "The one quality which most disquiets the Soviet government is the ability which they attribute to us to get others to do our fighting for us ... they respect not us, but our ability to collect friends".[13] Conversely, "the success or failure of United States foreign economic peace aims depended almost entirely on its ability to win or extract the co-operation of Great Britain".[14] Reflecting on the symbiosis, a later champion, former prime minister Margaret Thatcher, declared: "The Anglo-American relationship has done more for the defence and future of freedom than any other alliance in the world".[15][16]

Military cooperation

The intense level of military co-operation between the United Kingdom and United States began with the creation of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in December 1941, a military command with authority over all U.S. and British operations. Following the end of the Second World War the joint command structure was disbanded, but close military cooperation between the nations resumed in the early 1950s with the start of the Cold War.[1]

Shared military bases

Since the Second World War and the subsequent Berlin Blockade, the United States has maintained substantial forces in Great Britain. In July 1948, the first American deployment began with the stationing of B-29 bombers. Currently, an important base is the radar facility RAF Fylingdales, part of the US Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, although this base is operated under British command and has only one USAF representative for largely administrative reasons. Several bases with a significant US presence include RAF Menwith Hill (only a short distance from RAF Fylingdales), RAF Lakenheath and RAF Mildenhall.

Following the end of the Cold War, which was the main rationale for their presence, the number of US facilities in the United Kingdom has been reduced in number in line with the US military worldwide. Despite this, these bases have been used extensively in support of various peacekeeping and offensive operations of the 1990s and early 21st century.

The two nations also jointly operate on the British military facilities of Diego Garcia in the British Indian Ocean Territory and on Ascension Island, a dependency of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean.

Nuclear weapons development

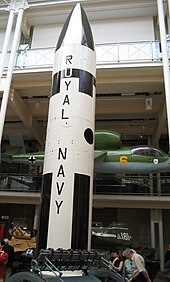

The Quebec Agreement of 1943 paved the way for the two countries to develop atomic weapons side by side, the United Kingdom handing over vital documents from its own Tube Alloys project and sending a delegation to assist in the work of the Manhattan Project. The United States later kept the results of the work to itself under the postwar McMahon Act, but after the United Kingdom developed its own thermonuclear weapons, the United States agreed to supply delivery systems, designs and nuclear material for British warheads through the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement.

The United Kingdom purchased first Polaris and then the U.S. Trident system which remains in use today. The 1958 agreement gave the United Kingdom access to the facilities at the Nevada Test Site, and from 1963 it conducted a total of 21 underground tests there before the cessation of testing in 1991.[17] The agreement under which this partnership operates was updated in 2004; anti-nuclear activists claimed renewal may breach the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.[18][19] The United States and the United Kingdom jointly conducted subcritical nuclear experiments in 2002 and 2006, to determine the effectiveness of existing stocks, as permitted under the 1998 Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.[20][21]

Military procurement

The United Kingdom is the only collaborative, or Level One, international partner in the largest US aircraft procurement project in history, the F-35 Lightning II program.[22][23] The United Kingdom was involved in writing the specification and selection and its largest defense contractor, BAE Systems is a partner of the American prime contractor Lockheed Martin. BAE Systems is also the largest foreign supplier to the United States Defense Department and has been permitted to buy important US defense companies such as Lockheed Martin Aerospace Electronic Systems and United Defense.

The US operates several British designs including Chobham Armour, the RAF Harrier GR9 or United States Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier II and the US Navy T-45 Goshawk. The UK also operates several American designs, including the Javelin anti-tank missile, M270 rocket artillery, the Apache gunship, C-130 Hercules and C-17 Globemaster transport aircraft.

Other areas of cooperation

Intelligence sharing

A cornerstone of the special relationship is the collecting and sharing of intelligence. This originated during World War II with the sharing of code breaking knowledge and led to the 1943 BRUSA Agreement, signed at Bletchley Park. After World War II the common goal of monitoring and countering the threat of communism prompted the UK-USA Security Agreement of 1948. This agreement brought together the SIGINT organizations of the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand and is still in place today (see: Five Eyes). The head of the CIA station in London attends each weekly meeting of the British Joint Intelligence Committee.[24]

One present-day example of such cooperation is the UKUSA Community, comprising the USA's National Security Agency, the United Kingdom's Government Communications Headquarters, Australia's Defence Signals Directorate and Canada's Communications Security Establishment collaborating on ECHELON, a global intelligence gathering system. Under classified bilateral accords, UKUSA members do not spy on each other.[25]

Following the discovery of the 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot, the CIA began to assist the Security Service (MI5) by running its own agent networks in the British Pakistani community. Security sources estimate 40 per cent of CIA activity to prevent a terrorist attack in the United States involves operations inside the United Kingdom.[citation needed] One intelligence official commented on the threat against the United States from British Islamists: "The fear is that something like this would not just kill people but cause a historic rift between the US and the UK".[26]

Economic policy

The United States is the largest source of foreign direct investment to the United Kingdom; likewise the United Kingdom is the largest single foreign direct investor in the United States.[27] British trade and capital have been important components of the American economy since its colonial inception. In trade and finance, the special relationship has been described as 'well-balanced', with London's 'light-touch' regulation in recent years attracting a massive outflow of capital from New York.[28] The key sectors for British exporters to the United States are aviation, aerospace, commercial property, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and heavy machinery.[29]

British ideas, classical and modern, have also exerted a profound influence on US economic policy, most notably the historian Adam Smith on free trade and the economist John Maynard Keynes on counter-cyclical spending, while the British government has adopted workfare reforms from the United States. U.S. and British investors share entrepreneurial attitudes towards the housing market, and the fashion and music industries of each country are major influences on their counterparts.[30] Trade ties have been strengthened by globalisation, while both governments agree on the need for currency reform in China and educational reform at home to increase their competitiveness against India's developing service industries.[30] In 2007 the US ambassador suggested to British business leaders that the special relationship could be used 'to promote world trade and limit environmental damage as well as combating terrorism'.[31]

In a press conference that made several references to the special relationship, US Secretary of State John Kerry, in London with UK Foreign Secretary William Hague on 9 September 2013, said

"We are not only each other’s largest investors in each of our countries, one to the other, but the fact is that every day almost one million people go to work in the United States for British companies that are in the United States, just as more than one million people go to work here in Great Britain for U.S. companies that are here. So we are enormously tied together, obviously. And we are committed to making both the U.S.-UK and the U.S.-EU relationships even stronger drivers of our prosperity."[32]

Personal relationships

The relationship often depends on the personal relations between British prime ministers and US presidents. The first example was the close relationship between Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt who were in fact distantly related.[33][34]

Prior to their collaboration during World War II Anglo-American relations had been somewhat frosty. President Woodrow Wilson and Prime Minister David Lloyd George in Paris had been the only previous leaders to meet face-to-face,[35] but had enjoyed nothing that could be described as a special relationship, although Lloyd George's wartime Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, got on well with Wilson during his time in the United States and helped convince the previously skeptical president to enter the war.

Churchill spent much time and effort cultivating the relationship which paid dividends for the war effort although it cost Britain much of her wealth and ultimately her empire. Two great architects of the special relationship on a practical level were Field Marshal Sir John Dill and General George Marshall, whose excellent personal relations and senior positions (Roosevelt was especially close to Marshall), oiled the wheels of the alliance considerably.

The links that were created during the war—such as the UK military liaison officers posted to Washington—persist. However, for Britain to gain any benefit from the relationship it became clear[who?] that a constant policy of personal engagement was required. Britain, starting off in 1941, as somewhat the senior partner, had found herself the junior. The diplomatic policy was thus two pronged, encompassing strong personal support and equally forthright military and political aid. These two have always operated in tandem, that is to say, the best personal relationships between British prime ministers and American presidents have always been those based around shared goals. For example, Harold Wilson's government would not commit troops to Vietnam. Wilson and Lyndon Johnson did not get on especially well.

Peaks in the special relationship include the bonds between Harold Macmillan (who like Churchill had an American mother) and John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter and James Callaghan were close personal friends despite their differences in personality, between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and more recently between Tony Blair and both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Nadirs have included Dwight D. Eisenhower's opposition to UK operations in Suez under Anthony Eden and Harold Wilson's refusal to enter the war in Vietnam.[36]

Macmillan and Kennedy

Macmillan famously quipped that it was Britain’s historical duty to guide the power of the United States as the ancient Greeks had the Romans.[37] He endeavoured to broaden the special relationship beyond Churchill’s conception of an English-Speaking Union into a more inclusive "Atlantic Community".[38] His key theme, 'of the interdependence of the nations of the Free World and the partnership which must be maintained between Europe and the United States', was one that Kennedy subsequently took up.[39]

On the prime minister's retirement in October 1963, the president declared: 'In nearly three years of cooperation, we have worked together on great and small issues, and we have never had a failure of understanding or of mutual trust.'[40] For his part, Macmillan confided to Kennedy's widow in February 1964: 'He seemed to trust me—and (as you will know) for those of us who have had to play the so-called game of politics—national and international—this is something very rare but very precious.'[41]

However, even in the celebrated 'golden days'[42] of the Kennedy-Macmillan partnership, the special relationship was tested, most severely by the Skybolt crisis of 1962, when Kennedy and his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, ignoring the British contribution to the development of the atomic bomb and reneging on a promise made by Eisenhower, tried to divest the United Kingdom of its nuclear deterrent by unilaterally cancelling a joint project without consultation.[43][44] Dean Acheson, a former US Secretary of State, also chose this moment to challenge publicly the special relationship and marginalise the British contribution to the Western alliance in his West Point speech of 1962:

Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role. The attempt to play a separate power role—that is, a role apart from Europe, a role based on a 'Special Relationship' with the United States, a role based on being the head of a 'Commonwealth' which has no political structure, or unity, or strength and enjoys a fragile and precarious economic relationship—this role is about played out.[45]

On learning of Acheson's attack, Macmillan thundered:

In so far as he appeared to denigrate the resolution and will of Britain and the British people, Mr. Acheson has fallen into an error which has been made by quite a lot of people in the course of the last four hundred years, including Philip of Spain, Louis XIV, Napoleon, the Kaiser and Hitler. He also seems to misunderstand the role of the Commonwealth in world affairs.

In so far as he referred to Britain's attempt to play a separate power role as about to be played out, this would be acceptable if he had extended this concept to the United States and to every other nation in the Free World. This is the doctrine of interdependence, which must be applied in the world today, if Peace and Prosperity are to be assured.

I do not know whether Mr. Acheson would accept the logical sequence of his own argument. I am sure it is fully recognised by the US administration and by the American people.[46]

The looming collapse of the alliance between the two thermonuclear powers forced Kennedy into an immediate volte-face at the Anglo-American summit in Nassau, where he agreed to sell Polaris as a replacement for the cancelled Skybolt. Richard E. Neustadt in his official investigation concluded the crisis in the special relationship had erupted because 'the president's "Chiefs" failed to make a proper strategic assessment of Great Britain's intentions and its capabilities'.[47]

The Skybolt crisis with Kennedy came on top of Eisenhower's wrecking of Macmillan's policy of détente with the Soviet Union at the May 1960 Paris summit, and the prime minister's resulting disenchantment with the special relationship contributed to his decision to seek an alternative in British membership of the European Economic Community (EEC).[48] According to a recent analyst: 'What the prime minister in effect adopted was a hedging strategy in which ties with Washington would be maintained while at the same time a new power base in Europe was sought.'[49] Even so, Kennedy assured Macmillan 'that relations between the United States and the UK would be strengthened not weakened, if the UK moved towards membership.'[50]

Wilson, Johnson and Nixon

Prime Minister Harold Wilson recast the alliance as a 'close relationship',[51] but neither he nor President Lyndon B. Johnson had any experience of foreign policy,[52] and Wilson's attempt to mediate in Vietnam, where the United Kingdom was co-chairman with the Soviet Union of the Geneva Conference, was unwelcome to the president,[53] who was rumoured to have called the prime minister a 'creep'.[54] 'I won't tell you how to run Malaysia and you don’t tell us how to run Vietnam,' Johnson snapped in 1965.[53] However relations were sustained by US recognition that Wilson was being criticised at home by his neutralist Labour left for not condemning US involvement in the war.[54][55]

Despite US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's insistence that the United Kingdom should 'pay the blood price' by sending troops to Vietnam as 'the unwritten terms of the Special Relationship',[56] Wilson refused to commit regular forces, only special forces instructors.[57] His stance was consistent with a burden-sharing arrangement agreed by Macmillan, whereby British forces had been concentrated against the Communist insurgency in Malaya. 30,000 British troops were still defending Malaysia in 1964 in an undeclared war with Indonesia.[53] Australia and New Zealand were Commonwealth allies that did commit regular forces to Vietnam.

The Johnson administration’s support for IMF loans delayed devaluation of sterling until 1967.[54] The United Kingdom's subsequent withdrawal from the Persian Gulf and East Asia 'came as a shock to the United States', where it was strongly opposed, British forces being especially valued for their out-of-area contribution.[58] In retrospect Wilson's moves to scale back Britain's global commitments and correct its balance of payments contrasted favourably with Johnson's overexertions which accelerated the United States' relative economic and military decline.[54]

Heath and Nixon

A Europeanist, Prime Minister Edward Heath preferred to speak of a '"natural relationship", based on shared culture and heritage', and stressed that the special relationship was 'not part of his own vocabulary'.[59]

The Heath-Nixon era was dominated by the United Kingdom's 1973 entry into the European Economic Community (EEC). Although the two leaders' 1971 Bermuda communiqué restated that entry served the interests of the Atlantic Alliance, American observers voiced concern that the British government's membership would impair its role as an honest broker, and that, because of the European goal of political union, the special relationship would only survive if it included the whole Community.[60]

Critics accused President Richard M. Nixon of impeding the EEC's inclusion in the special relationship by his economic policy,[61] which dismantled the postwar international monetary system and sought to force open European markets for US exports.[62] Detractors also slated the personal relationship at the top as 'decidedly less than special'; Prime Minister Edward Heath, it was alleged, 'hardly dared put through a phone call to Richard Nixon for fear of offending his new Common Market partners.'[63]

The special relationship was 'soured' during the Arab–Israeli War of 1973 when Nixon failed to inform Heath that US forces had been put on DEFCON 3 in a worldwide standoff with the Soviet Union, and US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger misled the British ambassador over the nuclear alert.[64] Heath, who learned about the alert only from press reports hours later, confessed: 'I have found considerable alarm as to what use the Americans would have been able to make of their forces here without in any way consulting us or considering the British interests.'[65] The incident marked 'a low ebb' in the special relationship.[66]

Callaghan, Ford and Carter

While President Gerald Ford never visited the United Kingdom,[67] the British government saw the US bicentennial in 1976 as an occasion to celebrate the special relationship. Political leaders and guests from both sides of the Atlantic gathered in May at Westminster Hall to mark the Declaration of Independence. Prime Minister Jim Callaghan presented a visiting US Congressional delegation with a gold-embossed reproduction of Magna Carta, symbolising the common heritage of the two nations. British historian Esmond Wright, of the Institute of US Studies, noted 'a vast amount of popular identification with the American story'. A year of cultural exchanges and exhibitions culminated in July in a state visit to the United States by The Queen.[68]

Ties between Callaghan and President Jimmy Carter were cordial but not emotional[69](Although Carter's Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and Callaghan's Foreign Secretary David Owen got on particularly well). When Carter came to London on his first foreign trip in May 1977 he described the relationship as 'very special'[67] but, with both left of centre-governments being preoccupied with economic malaise, diplomatic contacts remained low key. US officials characterised relations in 1978 as 'extremely good', with the main disagreement being over trans-Atlantic air routes.[70]

Reagan and Thatcher

After a period of disengagement and drift in the 1970s,[71] the personal friendship between President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, often described as 'ideological soul-mates',[72] reinvigorated what she affirmed as the ‘extraordinary alliance’.[73] They shared a commitment to the philosophy of the free market, low taxes, limited government, and a strong defence; they rejected détente and were determined to win the battle of ideas with the Soviet Union.[74]

Thatcher summed up her understanding of the special relationship at her first meeting with Reagan as president in 1981: ‘Your problems will be our problems and when you look for friends we shall be there.’[75] Celebrating the 200th anniversary of diplomatic relations in 1985, she enthused: ‘There is a union of mind and purpose between our peoples which is remarkable and which makes our relationship a truly remarkable one. It is special. It just is, and that’s that.’[76] The president acknowledged:

‘The United States and the United Kingdom are bound together by inseparable ties of ancient history and present friendship ... There's been something very special about the friendships between the leaders of our two countries. And may I say to my friend the Prime Minister, I'd like to add two more names to this list of affection—Thatcher and Reagan.’[77]

In 1982 Thatcher and Reagan reached an agreement to replace the British Polaris fleet with a force equipped with US-supplied Trident missiles, and Reagan became only the second foreign leader to address both Houses of Parliament (the first was de Gaulle in 1960).[67] The confidence between the two principals was momentarily strained by Reagan's belated support in the Falklands War, but this was more than countered by the Anglophile US Defense Secretary, Caspar Weinberger, who provided communications intercepts and approved shipments of the latest weapons to the massing British task force.[78][79] Thatcher later stood alone among Western allies[80][81] when she returned the favour by letting US F-111s take off from RAF bases for the 1986 bombing of Libya,[82][83] justifying it as an overdue move to help Reagan 'turn the tide against terrorism'.[84]

Feathers were also ruffled in 1983 over the lack of consultation before the US invasion of the Commonwealth island of Grenada.[85][86][87] In 1986 the British defence secretary Michael Heseltine, a prominent critic of the special relationship and a supporter of European integration, resigned over his concern that a takeover of Britain's last helicopter manufacturer by a US firm instead of a European consortium would harm the British defence industry.[88] Thatcher herself also saw a potential risk to Britain's deterrent and security posed by the Strategic Defense Initiative[89][90][91] and Reagan's proposal at the Reykjavík Summit to eliminate all ballistic nuclear weapons despite large conventional disparities.[92][93][94] Even so, an observer of the period concluded: 'Britain did indeed figure more prominently in American strategy than any other European power'.[95] Peter Hennessy, a leading historian, singles out the personal dynamic of 'Ron' and 'Margaret' in this success:

At crucial moments in the late 1980s, her influence was considerable in shifting perceptions in President Reagan's Washington about the credibility of Mr Gorbachev when he repeatedly asserted his intention to end the Cold War. That mercurial, much-discussed phenomenon, 'the special relationship,' enjoyed an extraordinary revival during the 1980s, with 'slips' like the US invasion of Grenada in 1983 apart, the Thatcher-Reagan partnership outstripping all but the prototype Roosevelt-Churchill duo in its warmth and importance. ('Isn't she marvellous'?' he would purr to his aides even while she berated him down the 'hot line.')[96]

Major, George H. W. Bush and Clinton

The special relationship waned for a time with the passing of the Cold War, despite intensive co-operation in the Gulf War. Thus, while it remained the case that: 'On almost all issues, Britain and the US are on the same side of the table. You cannot say that for other important allies such as France, Germany or Japan',[97] it was also acknowledged: ‘The disappearance of a powerful common threat, the Soviet Union, has allowed narrower disputes to emerge and given them greater weight.’[98]

Republican administrations had enjoyed strong links with the Conservative governments, and the new Democratic President Bill Clinton said he intended to maintain the special relationship, avowing: 'I'm a great Anglophile',[99] but he and Prime Minister John Major were 'an odd couple',[100] who 'got off on the wrong foot'.[101] Their personal relationship was described as ‘especially awful’, with the two leaders once refusing to speak to one another while dining side-by-side.[102]

Both the Conservatives[103] and Labour[104] had sent advisers to the United States to aid the rival candidates in the 1992 presidential election,[105] and it emerged that the Conservative government had allowed Home Office press officers to search files for evidence that Clinton had applied for British citizenship to avoid the Vietnam draft while a Rhodes scholar at Oxford in 1969; no evidence was found that he had.[106][107]

Major stood accused of letting the special relationship become a personal relationship with the losing candidate, President George H. W. Bush,[108] and of having 'bet on the wrong horse in the presidential race'.[109] The Economist predicted: 'the special relationship, declared dead scores of times since Suez, will soon face another burial'.[105] The Clinton administration did little to rebut a report in the New York Times in January 1993 that Major topped a 'Clinton enemies list'.[108] The president afterwards explained: ‘I was determined there would be no damage but I wanted the Tories to worry about it for a while.’[110] At Clinton's first meeting with Major in February 1993 Clinton joked that he was 'grateful that I got through this whole campaign with most of my time in England still classified.'[111]

The nuclear alliance—'the heart of the special relationship'—was weakened when Clinton extended a moratorium on tests in the Nevada desert in 1993, and pressed Major to agree to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.[112] The freeze was described by a British defence minister as 'unfortunate and misguided', as it inhibited validation of the ‘safety, reliability and effectiveness’ of fail-safe mechanisms on upgraded warheads for the British Trident II D5 missiles, and potentially the development of a new deterrent for the 21st century, leading Major to consider a return to Pacific testing,[113] and the Ministry of Defence to turn to computer simulation.[114] One analyst accused the United Kingdom of using safety and reliability as cover for testing a replacement warhead for the WE.177 free-fall bomb.[115] The moratorium weakened the case for British reliance on Trident,[116] resulting in the entente nucléaire with France in 1995 under a Joint Nuclear Commission.[117]

A genuine crisis in transatlantic relations blew up over Bosnia.[118] London and Paris resisted relaxation of the UN arms embargo,[119] and discouraged US escalation,[120] arguing that arming the Muslims or bombing the Serbs could worsen the bloodshed and endanger their peacekeepers on the ground.[121] US Secretary of State Warren Christopher's campaign to lift the embargo was rebuffed by Major and President Mitterrand in May 1993.[119] After the so-called 'Copenhagen ambush' in June 1993, where Clinton 'ganged up' with Chancellor Kohl to rally the European Community against the peacekeeping states, Major was said to be contemplating the death of the special relationship.[122] The following month the United States voted at the UN with non-aligned countries against Britain and France over lifting the embargo.[123]

By October 1993, Warren Christopher was bristling that Washington policy makers had been too 'Eurocentric', and declared that Western Europe was 'no longer the dominant area of the world'.[119] The US ambassador to London demurred, insisting it was far too early to put a 'tombstone' over the special relationship.[121] A senior US State Department official described Bosnia in the spring of 1995 as the worst crisis with the British and French since Suez.[124] By the summer US officials were doubting whether NATO had a future.[124]

The nadir had now been reached, and, along with NATO enlargement and the Croatian offensive in 1995 that opened the way for NATO bombing, the strengthening Clinton-Major relationship was later credited as one of three developments that saved the Western alliance.[124] The president acknowledged: 'John Major carried a lot of water for me and for the alliance over Bosnia. I know he was under a lot of political pressure at home, but he never wavered. He was a truly decent guy who never let me down. We worked really well together, and I got to like him a lot.'[124]

A rift opened in a further area. In February 1994, Major refused to answer Clinton's telephone calls for days over his decision to grant Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams a visa to visit the United States to agitate.[125] Adams was listed as a terrorist by London.[119] The US State Department, the CIA, the US Justice Department and the FBI all opposed the move on the grounds that it made the United States look 'soft on terrorism' and 'could do irreparable damage to the special relationship'.[126] Under pressure from Congress, the president hoped the visit would encourage the IRA to renounce violence.[127] While Adams offered nothing new, and violence escalated within weeks,[128] the president later claimed vindication after the IRA ceasefire of August 1994.[129] To the disappointment of the prime minister, Clinton lifted the ban on official contacts and received Adams at the White House on St. Patrick's Day 1995, despite the fact the paramilitaries had not agreed to disarm.[119] The rows over Northern Ireland and the Adams affair reportedly 'provoked incandescent Clintonian rages'.[130]

In November 1995, Clinton became only the second US president ever to address both Houses of Parliament,[67] but by the end of Major's premiership disenchantment with the special relationship had deepened to the point where the incoming British ambassador banned the 'hackneyed phrase' from the embassy.[131][132]

Blair, Clinton and George W. Bush

The election of British prime minister Tony Blair in 1997 brought an opportunity to revive what Clinton called the two nations' "unique partnership". At his first meeting with his new partner, the president said: "Over the last fifty years our unbreakable alliance has helped to bring unparalleled peace and prosperity and security. It's an alliance based on shared values and common aspirations."[133] The personal relationship was seen as especially close because the leaders were "kindred spirits" in their domestic agendas.[134] New Labour's Third Way, a moderate social-democratic position, was partly influenced by US New Democratic thinking.[135]

Co-operation in defence and communications still had the potential to embarrass Blair, however, as he strove to balance it with his own leadership role in the European Union (EU).[136] Enforcement of Iraqi no-fly zones[137] and US bombing raids on Iraq dismayed EU partners.[138] As the leading international proponent of humanitarian intervention, the "hawkish" Blair "bullied" Clinton to back diplomacy with force in Kosovo in 1999, pushing for deployment of ground troops to persuade the president "to do whatever was necessary" to win.[139][140]

The personal diplomacy of Blair and Clinton's successor, US president George W. Bush, further served to highlight the special relationship. Despite their political differences on non-strategic matters, their shared beliefs and responses to the international situation formed a commonality of purpose following the September 11 attacks in New York and Washington, D.C.. Blair, like Bush, was convinced of the importance of moving against the perceived threat to world peace and international order, famously pledging to stand "shoulder to shoulder" with Bush:

This is not a battle between the United States of America and terrorism, but between the free and democratic world and terrorism. We therefore here in Britain stand shoulder to shoulder with our American friends in this hour of tragedy, and we, like them, will not rest until this evil is driven from our world.[141]

Blair flew to Washington immediately after 9/11 to affirm British solidarity with the United States. In a speech to the United States Congress, nine days after the attacks, Bush declared "America has no truer friend than Great Britain."[142] Blair, one of few world leaders to attend a presidential speech to Congress as a special guest of the First Lady, received two standing ovations from members of Congress. Blair's presence at the presidential speech remains the only time in U.S. political history that a foreign leader was in attendance at an emergency joint session of the U.S. congress, a testimony to the strength of the US-UK alliance under the two leaders. Following that speech, Blair embarked on two months of diplomacy rallying international support for military action. The BBC calculated that, in total, the prime minister held 54 meetings with world leaders and travelled more than 40,000 miles (60,000 km).

Blair's leadership role in the Iraq War helped him to sustain a strong relationship with Bush through to the end of his time as prime minister, but it was unpopular within his own party and lowered his public approval ratings. It also alienated some of his European partners, including the leaders of France and Germany. Blair felt he could defend his close personal relationship with Bush by claiming it had brought progress in the Middle East peace process, aid for Africa and climate-change diplomacy.[143] However, it was not with Bush but with California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger that Blair ultimately succeeded in setting up a carbon-trading market, "creating a model other states will follow".[28][144]

The 2006 Lebanon War also exposed some minor differences in attitudes over the Middle East. The strong support offered by Blair and the Bush administration to Israel was not wholeheartedly shared by the British cabinet or the British public. On 27 July, Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett criticised the United States for "ignoring procedure" when using Prestwick Airport as a stop-off point for delivering laser-guided bombs to Israel.[145] On 17 August, The Independent reported that Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott had disparaged as "crap" Bush's efforts on the Middle East Roadmap, which Prescott felt had been a condition of his support for the war in Iraq.[146][147] Prescott said this was an inaccurate report of a private conversation.[148]

In November 2006, US State Department analyst Kendall Myers dismissed the special relationship as a "myth" with "no sense of reciprocity".[149] Myers was disowned by the State Department. Former Foreign Office minister Denis MacShane said: "Every little rat who feasted during the Bush years is now leaving the ship".[150]

Brown, George W. Bush and Obama

Although British Prime Minister Gordon Brown stated his support for the United States on assuming office in 2007,[151] he appointed ministers to the Foreign Office who had been critical of aspects of the relationship or of recent US policy.[152][153] A Whitehall source said: 'It will be more businesslike now, with less emphasis on the meeting of personal visions you had with Bush and Blair.'[154] British policy was that the relationship with the United States remained the United Kingdom's 'most important bilateral relationship'.[155]

Prior to his election as US president in 2008, Barack Obama, suggesting that Blair and Britain had been let down by the Bush administration, declared: 'We have a chance to recalibrate the relationship and for the United Kingdom to work with America as a full partner.'[156]

On meeting Brown as president for the first time in March 2009, Obama reaffirmed that 'Great Britain is one of our closest and strongest allies and there is a link and bond there that will not break... This notion that somehow there is any lessening of that special relationship is misguided... The relationship is not only special and strong but will only get stronger as time goes on.'[157] Commentators, however, noted that the recurring use of 'special partnership' by White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs could be signaling an effort to recast terms.[158]

The special relationship was also reported to be 'strained' after a senior US State Department official criticised a British decision to talk to the political wing of Hezbollah, complaining the United States had not been properly informed.[159][160] The protest came after the Obama administration had said it was prepared to talk to Hamas[161] and at the same time as it was making overtures to Syria and Iran.[162] A senior Foreign Office official responded: 'This should not have come as a shock to any official who might have been in the previous administration and is now in the current one.’[163]

In June 2009 the special relationship was reported to have 'taken another hit'[164] after the British government was said to be 'angry'[165][166] over the failure of the US to seek its approval before negotiating with Bermuda over the resettlement to the British overseas territory[167] of four ex-Guantanamo Bay inmates wanted by the People's Republic of China.[168] A Foreign Office spokesman said: 'It's something that we should have been consulted about.'[169] Asked whether the men might be sent back to Cuba, he replied: 'We are looking into all possible next steps.'[165] The move prompted an urgent security assessment by the British government.[170] Shadow Foreign Secretary William Hague demanded an explanation from the incumbent, David Miliband,[170] as comparisons were drawn with his previous embarrassment over the US use of Diego Garcia for extraordinary rendition without British knowledge,[171] with one commentator describing the affair as 'a wake-up call' and 'the latest example of American governments ignoring Britain when it comes to US interests in British territories abroad'.[172]

In August 2009 the special relationship was again reported to have 'taken another blow' with the release on compassionate grounds of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the man convicted of the 1988 Lockerbie Bombing, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said 'it was absolutely wrong to release Abdelbaset al-Megrahi', adding 'We are still encouraging the Scottish authorities not to do so and hope they will not'. Obama also commented that the release of al-Megrahi was a 'mistake' and 'highly objectionable'.[173]

In March 2010 Hillary Clinton's support for Argentina's call for negotiations over the Falkland Islands triggered a series of diplomatic protests from Britain[174] and renewed public scepticism about the value of the special relationship.[175][176] The British government rejected Clinton's offer of mediation after renewed tensions with Argentina were triggered by a British decision to drill for oil near the Falkland Islands.[177] The British government's long-standing position was that the Falklands were British territory, with all that this implied regarding the legitimacy of British commercial activities within its boundaries. British officials were therefore irritated by the implication that sovereignty was negotiable.[178][179][180][181]

Later that month, the Foreign Affairs Select Committee of the House of Commons suggested that the British government should be 'less deferential' towards the United States and focus relations more on British interests.[182][183] According to Committee Chair Mike Gapes, 'The UK and US have a close and valuable relationship not only in terms of intelligence and security but also in terms of our profound and historic cultural and trading links and commitment to freedom, democracy and the rule of law. But the use of the phrase "the special relationship" in its historical sense, to describe the totality of the ever-evolving UK-US relationship, is potentially misleading, and we recommend that its use should be avoided.'[183] In April 2010 the Church of England added its voice to the call for a more balanced relationship between Britain and the United States.[184]

Cameron and Obama

On David Cameron being elected as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on 11 May 2010, President Obama was the first foreign leader to offer his congratulations. Following the conversation Obama said:

'As I told the prime minister, the United States has no closer friend and ally than the United Kingdom, and I reiterated my deep and personal commitment to the special relationship between our two countries – a bond that has endured for generations and across party lines.'[185]

Former British Foreign Secretary William Hague responded to the President's overture by making Washington, D.C., his first port of call, commenting: 'We're very happy to accept that description and to agree with that description. The United States is without doubt the most important ally of the United Kingdom.' Meeting Hillary Clinton, Hague hailed the special relationship as 'an unbreakable alliance', and added: 'It's not a backward-looking or nostalgic relationship. It is one looking to the future from combating violent extremism to addressing poverty and conflict around the world.' Both governments confirmed their joint commitment to the war in Afghanistan and their opposition to Iran's nuclear programme.[186]

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 sparked a media firestorm against BP in the United States. The Christian Science Monitor observed that a "rhetorical prickliness" had come about from escalating Obama administration criticism of BP—straining the special relationship—particularly the repeated use of the term 'British Petroleum' even though the business no longer uses that name.[187] Cameron stated that he did not want to make the president's toughness on BP a US-UK issue, and noted that the company was balanced in terms of the number of its American and British shareholders.[188] The validity of the special relationship was put in question as a result of the 'aggressive rhetoric'.[189]

On 20 July, Cameron met with Obama during his first visit to the United States as prime minister. The two expressed unity in a wide range of issues, including the War in Afghanistan. During the meeting, Obama stated, "We can never say it enough. The United States and the United Kingdom enjoy a truly special relationship," then going on to say, "We celebrate a common heritage. We cherish common values. ... (And) above all, our alliance thrives because it advances our common interests."[190] Cameron stated in an interview during the trip that he wanted to build a strong relationship with the United States, Britain's "oldest and best ally." This is in fact a historical error - the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance is the oldest alliance that is still in force. Cameron further stated that, "from the times I've met Barack Obama before, we do have very, very close – allegiances and very close positions on all the key issues, whether that is Afghanistan or Middle East peace process or Iran. Our interests are aligned and we've got to make this partnership work."[188]

Cameron has tried to downplay the idealism of the special relationship and called for an end to the British fixation on the status of the relationship, stating that it's a natural and mutually beneficial relationship. He said, "...I am unapologetically pro-America. But I am not some idealistic dreamer about the special relationship. I care about the depth of our partnership, not the length of our phone calls. I hope that in the coming years we can focus on the substance, not endlessly fret about the form."[191]

The England v. USA World Cup encounter, which ended in a 1–1 draw, ended a bet between the two leaders in which Obama gave Cameron a Chicago beer called 'Goose Island 312' while Cameron presented Obama with a bottle of 'Hobgoblin', a beer from his constituency of Witney in Oxfordshire. Obama also took the moment to praise the way that Cameron had handled the Saville inquiry into Bloody Sunday.[192]

In January 2011, during a White House meeting with the President of France Nicolas Sarkozy, Obama declared: "We don't have a stronger friend and stronger ally than Nicolas Sarkozy, and the French people",[193] a statement which triggered outcry in the United Kingdom.[194][195] In May, however, Obama became the fourth US President to make a state visit to the UK. For the keynote speech, he became the third US President to address both Houses of Parliament after Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. Considered a rare privilege for a foreign leader, only Charles de Gaulle, Ronald Reagan, Nelson Mandela, Bill Clinton, Pope Benedict XVI and Nicolas Sarkozy had done so since the Second World War.[196][197][198][199] (George W. Bush was invited to address Parliament in 2003, but declined.[200])

In 2013 John Kerry remarked "The relationship between the US and UK has often been described as special or essential and it has been described thus simply because it is. It was before a vote the other day in Parliament and it will be for long after that vote." This comment was brought about after the parliament vote to not conduct military strikes against Syria. William Hague replied "So the United Kingdom will continue to work closely with the United States, taking a highly active role in addressing the Syria crisis and working with our closest ally over the coming weeks and months."[201]

In 2015, Cameron stated the US President calls him "bro" and described the "special relationship" between Washington and Westminster as "stronger than it has ever been".[202]

In March 2016, the US President criticised the British PM for becoming "distracted" over the intervention in Libya, a criticism that was also aimed at the French President.[203] A National Security Council spokesman sent an unsolicited email to the BBC limiting the damage done by stating that "Prime Minister David Cameron has been as close a partner as the president has had." [204]

Public opinion

It has been noted that secret defence and intelligence links 'that [have] minimal impact on ordinary people [play] a disproportionate role in the transatlantic friendship',[205] and perspectives on the special relationship differ.

Poll findings

A 1942 Gallup poll conducted after Pearl Harbor, before the arrival of US troops and Churchill's heavy promotion of the special relationship, showed wartime ally Russia was still more popular than the United States among 62% of Britons. However, only 6% had ever visited the United States and only 35% knew any Americans personally.[206]

In 1969 the United States was tied with the Commonwealth as the most important overseas connection for the British public, while Europe came in a distant third. By 1984, after a decade in the Common Market, Britons chose Europe as being most important to them.[207]

British opinion polls from the Cold War revealed ambivalent feelings towards the United States. Margaret Thatcher's 1979 agreement to base US cruise missiles in Britain was approved of by only 36% of Britons, and the number with little or no trust in the U.S.' ability to deal wisely with world affairs had soared from 38% in 1977 to 74% in 1984, by which time 49% wanted US nuclear bases in Britain removed, and 50% would have sent US-controlled cruise missiles back to the United States. At the same time, 59% of Britons supported their own country’s nuclear deterrent, with 60% believing Britain should rely on both nuclear and conventional weapons, and 66% opposing unilateral nuclear disarmament. 53% of Britons opposed dismantling the Royal Navy's Polaris submarines. 70% of Britons still considered Americans to be very or fairly trustworthy, and in case of war the United States was the ally trusted overwhelmingly to come to Britain's aid, and to risk its own security for the sake of Britain. The United States and Britain were also the two countries most alike in basic values such as willingness to fight for their country and the importance of freedom [freedom from what?].[208]

In 1986, 71% of Britons, questioned in a Mori poll the day after Ronald Reagan’s bombing of Libya, disagreed with Thatcher's decision to allow the use of RAF bases, while two thirds in a Gallup survey opposed the bombing itself, the reverse of U.S. opinion.[209]

The United Kingdom's all-time low poll rating in the United States came in 1994, during the split over Bosnia, when 56% of Americans interviewed considered Britons to be close allies.[210][211]

In a 1997 Harris poll published after Tony Blair's election, 63% of people in the United States viewed Britain as a close ally, up by one percent from 1996, 'confirming that the long-running "special relationship" with America's transatlantic cousins is still alive and well'.[212] Britain came second behind its colonial offshoot Canada, on 73%, while another offshoot, Australia, came third, on 48%.[213] Popular awareness of the historical link was fading in the parent country, however. In a 1997 Gallup poll, while 60% of the British public said they regretted the end of Empire and 70% expressed pride in the imperial past, 53% wrongly supposed that the United States had never been a British possession.[214]

In 1998, 61% of Britons polled by ICM said they believed they had more in common with U.S. citizens than they did with the rest of Europe. 64% disagreed with the sentence 'Britain does what the US government tells us to do.' A majority also backed Blair's support of Bill Clinton's strategy on Iraq, 42% saying action should be taken to topple Saddam Hussein, with 24% favouring diplomatic action, and a further 24%, military action. A majority of Britons aged 24 and over said they did not like Blair supporting Clinton over the Lewinsky scandal.[215]

A 2006 poll of the US public showed that the United Kingdom, as an 'ally in the war on terror' was viewed more positively than any other country. 76% of the U.S. people polled viewed the British as an 'ally in the War on Terror' according to Rasmussen Reports.[216] According to Harris Interactive, 74% of Americans viewed Great Britain as a 'close ally in the war in Iraq', well ahead of next-ranked Canada at 48%.

A June 2006 poll by Populus for The Times showed that the number of Britons agreeing that 'it is important for Britain’s long-term security that we have a close and special relationship with America' had fallen to 58% (from 71% in April), and that 65% believed that 'Britain's future lies more with Europe than America.'[217] Only 44%, however, agreed that 'America is a force for good in the world.' A later poll during the Israel-Lebanon conflict found that 63% of Britons felt that the United Kingdom was tied too closely to the United States.[218] A 2008 poll by The Economist showed that Britons' views differed considerably from Americans' views when asked about the topics of religion, values, and national interest. The Economist remarked:

For many Britons, steeped in the lore of how English-speaking democracies rallied around Britain in the Second World War, [the special relationship] is something to cherish. For Winston Churchill ... it was a bond forged in battle. On the eve of the war in Iraq, as Britain prepared to fight alongside America, Tony Blair spoke of the 'blood price' that Britain should be prepared to pay in order to sustain the relationship. In the United States, it is not nearly so emotionally charged. Indeed,U.S. politicians are promiscuous with the term, trumpeting their 'special relationships' with Israel, Germany and South Korea, among others. 'Mention the special relationship to Americans and they say yes, it's a really special relationship,' notes sardonically Sir Christopher Meyer, a former British ambassador to Washington.[219]

In January 2010 a Leflein poll conducted for Atlantic Bridge found that 57% of people in the U.S. considered the special relationship with Britain to be the world's most important bilateral partnership, with 2% disagreeing. 60% of people in the U.S. regarded Britain as the country most likely to support the United States in a crisis, while Canada came second on 24%, and Australia third on 4%.[220][221]

In May 2010, another poll conducted in the UK by YouGov revealed that 66% of those surveyed held a favourable view of the U.S. and 62% agreed with the assertion that America is Britain's most important ally. However, the survey also revealed that 85% of British citizens believe that the UK has little or no influence on American policies, and that 62% think that America does not consider British interests.[222]

1967 letter

In 1967 a group of prominent Americans sought to reaffirm the importance of close ties in a letter published in The Times of London, saying that the special relationship should remain a fundamental bilateral policy even if the United Kingdom entered the European Economic Community. They suggested that the two governments "begin to consider contingent means, including mutually beneficial trade and fiscal reforms, for saving and strengthening the historic relationship between our nations, whatever the outcome of the E.E.C. negotiations". Signatories included 10 senators, 29 members of the House of Representatives and a number of university presidents. The Times proposed a "wide Atlantic-based free trade area" as one possibility of a broader economic grouping.[223]

Friendly fire

In the 1991 Gulf War, nine British soldiers of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers were killed when a USAF A-10 Thunderbolt II attacked a group of two Warrior IFVs. Public controversy arose after US military authorities refused to allow USAF pilots to give evidence at a 1992 British inquest into the deaths, saying that they had already supplied all the relevant information.[224] The inquest jury returned a verdict of unlawful killing. The families of those killed accused the United States of 'double standards' after three US military officers were reprimanded for negligence after a separate incident involving the similar death of a US soldier. Tammy Groves, solicitor for the families, said: 'We have been denied any inquiry in the US; there have been no reprimands; and the pilots have not been named. The contrast could not be greater.'[225] Anne Leech, whose son was one of the British soldiers killed, said: 'They are supposed to be a friendly country, but it shows it only goes as far as they want it to ... Unless people are made accountable for what they do in these situations it will continue to happen.'[226]

President George H. W. Bush responded: 'My heart goes out to their families. But I see no reason in going beyond what we've already done to fully account for this terrible tragedy of war.'[224] Peter Atkinson, whose son was also killed, said: 'We met George Bush. He was trying to slide out of meeting us so I ran after him, collared him and told him what I thought. He said to me "You want the facts? ... Right, you'll get them." Months later they sent us a report. It was rubbish. All the relevant details had been censored out.'[227]

Further friendly fire incidents in the 2003 Iraq War, particularly a similar incident involving soldiers of the Blues and Royals brought assurances from officers and politicians that they would not hurt the close alliance: 'A situation like this does not mean anything of harm to the coalition, but in many ways it brings us closer together,' said RAF Group Captain Jon Fynes.[228] However the US government again refused to co-operate with the coroner’s investigations. This culminated in the United States attempting to prevent the release of cockpit videos—later leaked to The Sun—showing events leading to the death of Lance-Corporal Matty Hull of the Household Cavalry, and threatening newspapers that published them with prosecution.[229] The coroner slammed US 'intransigence', and the British press accused the Pentagon of operating 'in a no-fault zone', with The Daily Telegraph commenting: 'This will reaffirm the view of many in the British military that while the US has the best kit, it does not necessarily have the best training ... Uninhibited by the risk of any sanction, is it any wonder that they go about their lethal business with such apparent insouciance?'[230] The Spectator described the British forbearance towards American evasiveness as "a bleak parable of the flaws at the heart of the US-UK 'special relationship'."[231]

Iraq

Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, senior British figures criticized the refusal of the US Government to heed British advice regarding post-war plans for Iraq, specifically the Coalition Provisional Authority's de-Ba'athification policy and the critical importance of preventing the power vacuum in which the insurgency subsequently developed. British defence secretary Geoff Hoon later stated that the United Kingdom 'lost the argument' with the Bush administration over rebuilding Iraq.[232] Speaking on the same topic, The Duke of York said there were "occasions when people in the UK would wish that those in responsible positions in the US might listen and learn from our experiences",[233] that there was 'healthy skepticism' in the United Kingdom toward what was said in Washington DC,[234] and a feeling of 'why didn't anyone listen to what was said and the advice that was given'.[235] CNN acknowledged that the Prince's views were widely shared in the UK.[236]

Extraordinary rendition

Assurances made by the United States to the United Kingdom that 'extraordinary rendition' flights had never landed on British territory were later shown to be false when official US records proved that such flights had landed at Diego Garcia repeatedly.[237] The revelation was an embarrassment for former British foreign secretary David Miliband, who was obliged to apologise to Parliament, describing the incidents as 'a most serious matter'.[238][239]

Legal and moral doubts also arose over the US government's extraordinary rendition process,[240] which ignored extradition treaties and officially sanctioned the kidnap and extrajudicial transfer of people (some of them British citizens), from one country to another, sometimes to one of their covert CIA-run prisons, known as black sites, other times to Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[241] The United Kingdom's Intelligence and Security Committee stated that America's failure to heed British concerns had 'serious implications' for future intelligence relations.[242]

Criminal law

In 2003 the United States pressed the United Kingdom to agree to an extradition treaty which, proponents claimed, allowed for equal extradition requirements between the two countries.[243][244] Critics argued that the United Kingdom was obligated to make a strong prima facie case to US courts before extradition would be granted,[245][246] and that, by contrast, extradition from the United Kingdom to the United States was a matter of administrative decision alone, without prima facie evidence.[247] This had been implemented as an anti-terrorist measure in the wake of the 11 September 2001 attacks. Very soon, however, it was being used by the United States to extradite and prosecute a number of high-profile London businessmen (e.g., the Natwest Three and Ian Norris[248]) on fraud charges. Contrasts have been drawn with the United States' harboring of Provisional IRA terrorists in the 1970s through to the 1990s and repeated refusals to extradite them to the UK.[249]

On 30 September 2006, the US Senate unanimously ratified the 2003 treaty. Ratification had been slowed by complaints from some Irish-American groups that the treaty would create new legal jeopardy for US citizens who opposed British policy in Northern Ireland.[250] The Spectator condemned the three-year delay as 'an appalling breach in a long-treasured relationship’.[251]

The United States also refused to accede to another priority of the Blair government, the treaty setting-up the International Criminal Court.[252]

Trade policy

Trade disputes and attendant job fears have sometimes strained the special relationship. The United States has been accused of pursuing an aggressive trade policy, using or ignoring WTO rules; the aspects of this causing most difficulty to the United Kingdom have been a successful challenge to the protection of small family banana farmers in the West Indies from large US corporations such as the American Financial Group,[253] and high tariffs on British steel products.[254] In 2002, Blair denounced Bush's imposition of tariffs on steel as 'unacceptable, unjustified and wrong', but although Britain's biggest steelmaker, Corus, called for protection from dumping by developing nations, the Confederation of British Industry urged the government not to start a 'tit-for-tat'.[255]

Diplomacy

In October 2007, the United Kingdom's first Muslim government minister, Shahid Malik, rebuked US authorities after having been detained and searched for explosives at a Washington airport on his way home from a meeting with the US Department of Homeland Security.[256][257] This was the second occasion on which this Member of Parliament had been detained and searched, having received the same treatment at JFK airport during a visit to the United States in November 2006. Mr Malik remarked, "The abusive attitude I endured last November I forgot about and I forgave, but I really do believe that British ministers and parliamentarians should be afforded the same respect and dignity at USA airports that we would bestow upon our colleagues in the Senate and Congress."[258]

The ongoing refusal of the US embassy in Grosvenor Square to pay the London congestion charge has also been a minor source of controversy.[259] Embassy officials claimed they did not have to pay the congestion charge because it was a tax, from which diplomats were exempt. London officials asserted that the congestion charge was no different from the toll charges paid by drivers to travel into US cities such as New York City via bridges and roads. US embassies paid similar congestion charges in Singapore and Oslo.[260]

See also

References

- ^ a b James, Wither (March 2006). "An Endangered Partnership: The Anglo-American Defence Relationship in the Early Twenty-first Century". European Security. 15 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1080/09662830600776694. ISSN 0966-2839.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Existence since the 19th century:

- "The Anglo-American Arbitration Treaty". The Times. 14 January 1897. p. 5, col. C., quoting the "semi-official organ" the North-German Gazette: "There is, therefore, not the slightest occasion for other States to adopt as their model and example a form of agreement which may, perhaps, be advantage to England and America in their special relationship".

- "The New American Ambassador". The Times. 7 June 1913. p. 9, col. C. "No Ambassador to this or any other nation is similarly honoured ... It is intended to be, we need hardly say, precisely what it is, a unique compliment, a recognition on our part that Great Britain and the United States stand to one another in a special relationship, and that between them some departure from the merely official attitude is most natural".

- "The Conference and the Far East". The Times. 21 November 1921. p. 11, col. B, C. "The answer of the [Japanese] Ambassador [Baron Kato] shows that he and his Government even then [1911] appreciated the special relationship between this country [the United Kingdom] and the United States ... That, probably, the Japanese Government understands now, as clearly as their predecessors understood in 1911 that we could never make war on the United States".

- "Limit of Navy Economies". The Times. 13 March 1923. p. 14, col. F. "After comparing the programmes of Britain, America, and Japan, the First Lord said that so far from importing into our maintenance of the one-Power standard a spirit of keen and jealous competition, we had, on the contrary, interpreted it with a latitude which could only be justified by our desire to avoid provoking competition and by our conception of the special relationship of good will and mutual understanding between ourselves and the United States".

- "Five Years Of The League". The Times. 10 January 1925. p. 13, col. C. "As was well pointed out in our columns yesterday by Professor Muirhead, Great Britain stands in a quite special relationship to that great Republic [the United States]".

- "The Walter Page Fellowships. Mr. Spender's Visit To America., Dominant Impressions". The Times. 23 February 1928. p. 16, col. B. quoting J. A. Spender: "The problem for British and Americans was to make their special relationship a good relationship, to be candid and open with each other, and to refrain from the envy and uncharitableness which too often in history had embittered the dealings of kindred peoples".

- ^ Cowling, Maurice (1974). The Impact of Hitler: British Politics and British Policy 1933–1940. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Reynolds, David (April 1990). "1940: Fulcrum of the Twentieth Century?". International Affairs. 66 (2): 331. doi:10.2307/2621337.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Acheson, Dean (1969). Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 387.

- ^ Reynolds 1990, pp. 325, 348–50

- ^ Lindley, Ernest K. (9 March 1946). "Churchill's Proposal". Washington Post. p. 7.

- ^ Skidelsky, Robert (9 September 1971). "Those Were the Days". New York Times. p. 43.

- ^ Gunther, John (1950). Roosevelt in Retrospect. Harper & Brothers. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Reynolds, David (1985). "The Churchill government and the black American troops in Britain during World War II". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 35: 113–133. doi:10.2307/3679179.

- ^ a b "Special relationship". Phrases.org.uk. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Webley, Simon (Autumn 1989). "Review: 'The Politics of the Anglo-American Economic Special Relationship', by Alan J. Dobson". International Affairs. 65 (4): 717. doi:10.2307/2622608.

- ^ Coker, Christopher (July 1992). "Britain and the New World Order: The Special Relationship in the 1990s". International Affairs. 68 (3): 408. doi:10.2307/2622963.

- ^ Kolko, Gabriel (1968). The Politics of War: The World and United States Foreign Policy, 1943–1945. New York: Random House. p. 488.

- ^ Robinson, Eugene (19 October 1993). "Clinton's Remarks Cause Upper Lips to Twitch". Washington Post. p. a18.

- ^ Fletcher, Martin; Binyon, Michael (22 December 1993). "Special Relationship Struggles to Bridge the Generation Gap—Anglo-American". The Times.

- ^ 'Time Runs Out as Clinton Dithers over Nuclear Test', Independent On Sunday (20 June 1993), p. 13.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor, Nuclear weapons treaty may be illegal, The Guardian (27 July 2004). Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ Michael Smith, Focus: Britain's secret nuclear blueprint, Sunday Times (12 March 2006). Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ Andrea Shalal-Esa, 'Update 1-US, 'Britain conduct Nevada nuclear experiment', Reuters News (15 February 2002).

- ^ Ian Bruce, 'Britain working with US on new nuclear warheads that will replace Trident force', The Herald (10 April 2006), p. 5.

- ^ Kristin Roberts, 'Italy, Netherlands, Turkey seen as possible JSF partners', Reuters News (13 March 2001).

- ^ Douglas Barrie and Amy Butler, 'Dollars and Sense; Currency rate headache sees industry seek remedy with government', Aviation Week & Space Technology, vol. 167, iss. 23 (10 December 2007), p. 40.

- ^ "Why no questions about the CIA?". New Statesman. September 2003.

- ^ Bob Drogin and Greg Miller, 'Purported Spy Memo May Add to US Troubles at UN', Los Angeles Times (4 March 2003).

- ^ Tim Shipman, 'Why the CIA has to spy on Britain', The Spectator (28 February 2009), pp. 20–1.

- ^ "Country Profiles: United States of America" on UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office website

- ^ a b Irwin Seltzer, 'Britain is not America's economic poodle', The Spectator (30 September 2006), p. 36.

- ^ 'International Trade – The 51st State?', Midlands Business Insider (1 July 2007).

- ^ a b Seltzer, 'Not America's economic poodle', p. 36.

- ^ 'Special ties should be used for trade and the climate says US ambassador', Western Daily Press (4 April 2007), p. 36.

- ^ "Press Conference by Kerry, British Foreign Secretary Hague". United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London: U.S. Department of State. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Spencer family

- ^ Darryl Lundy. "Rt. Hon. Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill". thePeerage.com. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- ^ Michael White, Special relationship? Good and bad times, The Guardian (3 March 2009). Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ Robert M. Hendershot, Family Spats: Perception, Illusion, and Sentimentality in the Anglo-American Special Relationship (2008)

- ^ Alistair Horne, Macmillan, 1894–1956: Volume I of the Official Biography (London: Macmillan, 1988), p. 160.

- ^ Christopher Coker, 'Britain and the New World Order: The Special Relationship in the 1990s', International Affairs, Vol. 68, No. 3 (Jul., 1992), p. 408.

- ^ Harold Macmillan, At the End of the Day (London: Macmillan, 1973), p. 111.

- ^ John Dickie, Special No More: Anglo-American Relations: Rhetoric and Reality (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1994), p. 105.

- ^ Alistair Horne, Macmillan 1957–1986: Volume II of the Official Biography (London: Macmillan, 1989), p. 304.

- ^ Dickie, Special No More, p. 105.

- ^ Myron A. Greenberg, 'Kennedy's Choice: The Skybolt Crisis Revisited', Naval War College Review, Autumn 2000.

- ^ Horne, Macmillan: Volume II, pp. 433–37.

- ^ Horne, Macmillan: Volume II of the Official Biography (London: Macmillan, 1989), p. 429.

- ^ Macmillan to Oliver Lyttelton, Lord Chandos, 7 December 1962, quoted in Macmillan, At the End of the Day, p. 339.

- ^ Greenberg, 'Kennedy's Choice'.

- ^ Nigel J. Ashton, 'Harold Macmillan and the "Golden Days" of Anglo-American Relations Revisited', Diplomatic History, Vol. 29, No. 4 (2005), pp. 696, 704.

- ^ Ashton, 'Anglo-American Relations Revisited', p. 705.

- ^ David Reynolds, 'A "Special Relationship"? America, Britain and the International Order Since the Second World War', International Affairs, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Winter, 1985–1986), p. 14.

- ^ Reynolds, 'A "Special Relationship"?', p. 1.

- ^ Gle O'Hara, Review: A Special Relationship? Harold Wilson, Lyndon B. Johnson and Anglo-American Relations "At the Summit", 1964–1968 by Jonathan Colman, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Apr., 2006), p. 481.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, 'A "Special Relationship"?', p. 14.

- ^ a b c d O'Hara, Review, p. 482.

- ^ Ashton, 'Anglo-American Relations Revisited', p. 694.

- ^ Ben Macintyre, 'Blair's real special relationship is with us, not the US – Comment – Opinion', The Times (7 September 2002), p. 22.

- ^ Robert M. Hendershot, Family Spats: Perception, Illusion, and Sentimentality in the Anglo-American Special Relationship VDM Verlag, 2008. ISBN 978-3-639-09016-1

- ^ Reynolds, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Ronald Koven, 'Heath Gets Bouquets, But Few Headlines', Washington Post (5 February 1973), p. A12.

- ^ Editorial, New York Times (24 December 1971), p. 24, col. 1.

- ^ New York Times (24 December 1971).

- ^ Allen J. Matusow, 'Richard Nixon and the Failed War Against the Trading World', Diplomatic History, vol. 7, no. 5 (November 2003), pp. 767–8.

- ^ Henrik Bering-Jensen, 'Hawks of a Feather', Washington Times (8 April 1991), p. 2.

- ^ Paul Reynolds, UK in dark over 1973 nuclear alert, BBC News (2 January 2004). Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ 'America "misled Britain" in Cold War; National archives: 1973', The Times (1 January 2004), p. 10.

- ^ ‘Nixon nuclear alert left Heath fuming’, The Express (1 January 2004), p. 8.

- ^ a b c d 'Thatcher Hero and the Leader of Free World Basks in Glory', The Guardian (25 November 1995), p. 8.

- ^ Robert B. Semple, Jr, 'British Government Puts on its Biggest Single Show of Year to Mark Declaration of Independence', New York Times (27 May 1976), p. 1, col. 2.

- ^ 'Neil Kinnock to meet President Bush during visit', The Guardian (16 July 1990).