Thriller film

Thriller film, also known as suspense film or suspense thriller, is a broad film genre that involves excitement and suspense in the audience.[1] The suspense element, found in most films' plots, is particularly exploited by the filmmaker in this genre. Tension is created by delaying what the audience sees as inevitable, and is built through situations that are menacing or where escape seems impossible.[2]

The cover-up of important information from the viewer, and fight and chase scenes are common methods. Life is typically threatened in thriller film, such as when the protagonist does not realize that they are entering a dangerous situation. Thriller films' characters conflict with each other or with an outside force, which can sometimes be abstract. The protagonist is usually set against a problem, such as an escape, a mission, or a mystery.[3]

Thriller films are typically hybridized with other genres; hybrids commonly including: action thrillers, adventure thrillers, fantasy and science fiction thrillers. Thriller films also share a close relationship with horror films, both eliciting tension. In plots about crime, thriller films focus less on the criminal or the detective and more on generating suspense. Common themes include, terrorism, political conspiracy, pursuit and romantic triangles leading to murder.[3]

In 2001, the American Film Institute made its selection of the top 100 greatest American "heart-pounding" and "adrenaline-inducing" films of all time. The 400 nominated films had to be American-made films whose thrills have "enlivened and enriched America's film heritage". AFI also asked jurors to consider "the total adrenaline-inducing impact of a film's artistry and craft".[4][3]

History

1920s–1930s

One of the earliest thriller films was Harold Lloyd's comedy Safety Last! (1923), with a character performing a daredevil stunt on the side of a skyscraper. Alfred Hitchcock's first thriller was his third silent film, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926), a suspenseful Jack the Ripper story. His next thriller was Blackmail (1929), his and Britain's first sound film.[6][7] His notable 1930s thrillers include The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935) and The Lady Vanishes (1938), the latter two ranked among the greatest British films of the 20th century.[8]

One of the earliest spy films was Fritz Lang's Spies (1928), the director's first independent production, with an anarchist international conspirator and criminal spy character named Haghi (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), who is pursued by good-guy Agent No. 326 (Willy Fritsch)—this film would be an inspiration for the future James Bond films. The German film M (1931), directed by Fritz Lang, starred Peter Lorre (in his first film role) as a criminal deviant who preys on children.

1940s–1960s

Hitchcock continued his suspense-thrillers, directing Foreign Correspondent (1940), the Oscar-winning Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941), Saboteur (1942) and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), which was Hitchcock's own personal favorite. Notable non-Hitchcock films of the 1940s include The Spiral Staircase (1946) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

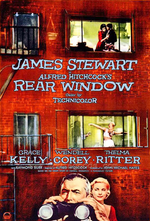

In the 1950s, Hitchcock added technicolor to his thrillers, now with exotic locales. He reached the zenith of his career with a succession of classic films such as, Strangers on a Train (1951), Dial M For Murder (1954) with Ray Milland, Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). Non-Hitchcock thrillers of the 1950s include The Night of the Hunter (1955)—Charles Laughton's only film as director—and Orson Welles's crime thriller Touch of Evil (1958).

Director Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960) featured Carl Boehm as a psychopathic cameraman. After Hitchcock's classic films of the 1950s, he produced Psycho (1960) about a lonely, mother-fixated motel owner and taxidermist. J. Lee Thompson's Cape Fear (1962), with Robert Mitchum, had a menacing ex-con seeking revenge. A famous thriller at the time of its release was Wait Until Dark (1967) by director Terence Young, with Audrey Hepburn as a victimized blind woman in her Manhattan apartment.

1970s–1980s

The 1970s saw an increase of violence in the thriller genre, beginning with Canadian director Ted Kotcheff's Wake in Fright (1971), which almost completely overlapped with the horror genre, and Frenzy (1972), Hitchcock's first British film in almost two decades, which was given an R rating for its vicious and explicit strangulation scene.

One of the first films about a fan's being disturbingly obsessed with their idol was Clint Eastwood's directorial debut, Play Misty for Me (1971), about a California disc jockey pursued by a disturbed female listener (Jessica Walter). John Boorman's Deliverance (1972) followed the perilous fate of four Southern businessmen during a weekend's trip. In Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974), a bugging-device expert (Gene Hackman) systematically uncovered a covert murder while he himself was being spied upon.

Alan Pakula's The Parallax View (1974) told of a conspiracy, led by the Parallax Corporation, surrounding the assassination of a presidential-candidate US Senator that was witnessed by investigative reporter Joseph Frady (Warren Beatty). Peter Hyam's science fiction thriller Capricorn One (1978) proposed a government conspiracy to fake the first mission to Mars.

Brian De Palma usually had themes of guilt, voyeurism, paranoia, and obsession in his films, as well as such plot elements as killing off a main character early on, switching points of view, and dream-like sequences. His notable films include Sisters (1973); Obsession (1976), which was slightly inspired by Vertigo; Dressed to Kill (1980); and the assassination thriller Blow Out (1981).

1990s–present

In the early 1990s, thrillers had recurring elements of obsession and trapped protagonists who must find a way to escape the clutches of the villain—these devices influenced a number of thrillers in the following years. Rob Reiner's Misery (1990), based on a book by Stephen King, featured Kathy Bates as an unbalanced fan who terrorizes an incapacitated author (James Caan) who is in her care. Other films include Curtis Hanson's The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992) and Unlawful Entry (1992), starring Ray Liotta.[9]

Detectives/FBI agents hunting down a serial killer was another popular motif in the 1990s. A famous example is Jonathan Demme's Best Picture–winning crime thriller The Silence of the Lambs (1991)—in which young FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) engages in a psychological conflict with a cannibalistic psychiatrist named Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) while tracking down transgender serial killer Buffalo Bill—and David Fincher's crime thriller Seven (1995), about the search for a serial killer who re-enacts the seven deadly sins.

Another notable example is Martin Scorsese's neo-noir psychological thriller Shutter Island (2010), in which a U.S. Marshal must investigate a psychiatric facility after one of the patients inexplicably disappears.

In recent years, thrillers have often overlapped with the horror genre, having more gore/sadistic violence, brutality, terror and frightening scenes. The recent films in which this has occurred include Eden Lake (2008), The Last House on the Left (2009), P2 (2007), Captivity (2007), and Vacancy (2007). Action scenes have also gotten more elaborate in the thriller genre. Films such as Unknown (2011), Hostage (2005), and Cellular (2004) have crossed over into the action genre.

Sub-genres

The thriller film genre includes the following sub-genres:[10]

- Action thriller: A subgenre of both action film and thriller in which the protagonist confronts dangerous adversaries, obstacles, or situations which he/she must conquer, normally in an action setting. Action thrillers usually feature a race against the clock, weapons and explosions, frequent violence, and a clear antagonist.[11] Examples include Dirty Harry, Taken,[12] The Fugitive,[13] Snakes on a Plane, Speed, The Dark Knight, Casino Royale,[14] The Hurt Locker,[15] The Terminator, Battle Royale, the Die Hard series, and the Bourne series.[16]

- Comedy thriller: A genre that combines elements of humor with suspense. Such films include Silver Streak, Dr. Strangelove, Charade, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, In Bruges, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Grosse Point Blank, The Thin Man, The Big Fix, and The Lady Vanishes.

- Conspiracy thriller: A genre in which the hero/heroine confronts a large, powerful group of enemies whose true extent only s/he recognizes. The Chancellor Manuscript and The Aquitaine Progression by Robert Ludlum fall into this category, as do films such as Awake, Snake Eyes, The Da Vinci Code, Edge of Darkness,[17] Absolute Power, Marathon Man, In the Line of Fire, Capricorn One, and JFK.[18]

- Crime thriller: This genre is a hybrid type of both crime films and thrillers, which offers a suspenseful account of a successful or failed crime or crimes. Such films often focus on the criminal(s) rather than a policeman. Central topics include serial killers/murders, robberies, chases, shootouts, heists, and double-crosses. Some examples of crime thrillers involving murderers are Seven,[19] No Country for Old Men, Heat, New Jack City, , Untraceable, Mindhunters,[20] Kiss the Girls, Along Came a Spider, Collateral, and Copycat.[21] Examples of crime thrillers involving heists or robberies are The Asphalt Jungle,[22] The Score,[23] Rififi, Entrapment,[24] Heat, and The Killing.

- Erotic thriller: A type of thriller that has an emphasis on eroticism and where a sexual relationship plays an important role in the plot. It has become popular since the 1980s and the rise of VCR market penetration. The genre includes such films as Sea of Love, Basic Instinct,[25] Chloe, Color of Night, Dressed to Kill, Eyes Wide Shut, In the Cut, Lust, Caution, and Single White Female.

- Giallo: An Italian thriller subgenre that combines elements of mystery, thriller, slasher, and psychological horror. It deals with an unknown killer murdering people, with the main protagonist having to find out who the killer is. The genre was popular during the late 1960s-late 1970s and is still being produced today, albeit less commonly. Examples include The Girl Who Knew Too Much, Blood and Black Lace, Deep Red, The Red Queen Kills Seven Times, Don't Torture a Duckling, Tenebrae, Opera , and Sleepless.

- Legal thriller: A suspense film in which the major characters are lawyers and their employees. The system of justice itself is always a major part of these works, at times almost functioning as one of the characters. Examples include The Pelican Brief, Presumed Innocent, The Jury, The Client, The Lincoln Lawyer, Hostile Witness, and Silent Witness.

- Political thriller: A type of film in which the hero/heroine must ensure the stability of the government. The success of Seven Days in May (1962) by Fletcher Knebel, The Day of the Jackal (1971) by Frederick Forsyth, and The Manchurian Candidate (1959) by Richard Condon established this subgenre. Other examples include Topaz, Notorious, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Interpreter,[26] Proof of Life,[27] State of Play, and The Ghost Writer.

- Psychological thriller: In this type of film (until the often violent resolution), the conflict between the main characters is mental and emotional rather than physical. Characters, either by accident or their own curiousness, are dragged into a dangerous conflict or situation that they are not prepared to resolve. To overcome their brutish enemies characters are reliant not on physical strength but on their mental resources. This subgenre usually has elements of drama, as there is an in-depth development of realistic characters who must deal with emotional struggles.[28] The Alfred Hitchcock films Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, and Strangers on a Train, as well as David Lynch's bizarre and influential Blue Velvet, are notable examples of the type, as are The Talented Mr. Ripley, The Machinist,[29] Flightplan, Shutter Island, Secret Window, Identity, Gone Girl, Red Eye,[30] Phone Booth, Fatal Attraction, The River Wild,[31] Panic Room,[32] Misery, Cape Fear, and Funny Games.[33]

- Social thriller: A type of thriller that uses suspense to augment attention to abuses of power and instances of oppression in society. This new subgenre gained notoriety in 2017 with the release of Get Out.[34]

- Spy film: A film in which the protagonist is generally a government agent who must take violent action against agents of a rival government or (in recent years) terrorists. The subgenre often deals with the subject of espionage in a realistic way (as in the adaptations of John Le Carré's novels). It is a significant aspect of British cinema,[35] with leading British directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Carol Reed making notable contributions, and many films set in the British Secret Service.[36] Thrillers within this subgenre include Spy Game, Hanna, Traitor, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Tourist, The Parallax View, The Tailor of Panama, Mission Impossible, Unknown, The Recruit, the James Bond franchise, The Debt, The Good Shepherd, and Three Days of the Condor.[37]

- Supernatural thriller: Films that include an otherworldly element (such as fantasy or the supernatural) mixed with tension, suspense, or plot twists. Sometimes the protagonist or villain has some psychic ability and superpowers. Examples include Fallen,[38] Frequency, In Dreams,[39] Flatliners, Jacob's Ladder, The Skeleton Key,[40] What Lies Beneath, Unbreakable, The Sixth Sense,[41] The Gift,[42] The Dead Zone, and Horns.[43]

- Techno-thriller: A suspenseful film in which the manipulation of sophisticated technology plays a prominent part. Examples include The Thirteenth Floor, I, Robot, Source Code, Eagle Eye, Supernova, Hackers, The Net, Futureworld, eXistenZ, and Virtuosity.

See also

Notes

- ^ Konigsberg 1997, p. 421

- ^ Konigsberg 1997, p. 404

- ^ a b c Dirks, Tim. "Thriller – Suspense Films". Filmsite.org. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 THRILLS". American Film Institute. 2001. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rear Window Movie Reviews, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes". Rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Richard Allen, S. Ishii-Gonzalès. Hitchcock: Past and Future. p.xv. Routledge (2004). ISBN 0415275253

- ^ Music Hall Mimesis in British Film, 1895–1960: on the halls on the screen p.79. Associated University Presse (2009). ISBN 9780838641910.

- ^ "British Film Institute - Top 100 British Films". cinemarealm.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Thriller and Suspense Films". Filmsite.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Thriller/Suspense Subgenre Definitions". Cuebon.com. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ "Action Thriller". AllRovi. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "Taken – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ The Fugitive (1993) AllMovie

- ^ "Casino Royale – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "The Hurt Locker – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "Hollywood readying new wave action thrillers". ew.com. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ "Edge of Darkness – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. January 29, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "JFK – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Seven – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Mindhunters – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. May 13, 2005. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Copycat – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Asphalt Jungle – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. June 8, 1950. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Score – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. July 13, 2001. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Entrapment – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Basic Instinct – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. March 20, 1992. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Interpreter – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. April 22, 2005. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Proof of Life – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. December 8, 2000. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Psychological Thriller Movies and Films – Find Psychological Thriller Movie Recommendations, Casts, Reviews, and Summaries". AllRovi. October 24, 2011. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Oksenhorn, Stewart (7 December 2004). "'The Machinist': a haunting psychological thriller". The Aspen Times. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Red Eye – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards". AllRovi. August 19, 2005. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The River Wild – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards". AllRovi. October 24, 2011. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Panic Room – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards". AllRovi. March 29, 2002. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Funny Games – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. March 14, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (February 14, 2017). "Get Out's Jordan Peele Brings the 'Social Thriller' to BAM | Village Voice". Village Voice. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "The Spying Game: British Cinema and the Secret State", 2009 Cambridge Film Festival, pp.54-57 of the festival brochure. Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geoffrey Macnab, "Spy movies – The guys who came in from the cold", The Independent, 2 October 2009.

- ^ Filmsite.org

- ^ "Fallen – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "In Dreams – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. January 15, 1999. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "The Skeleton Key – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. August 12, 2005. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (26 July 2010). "Spoiler alert: The Sixth Sense voted film with best twist". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Billy Bob Thornton. "The Gift – Cast, Reviews, Summary, and Awards – AllRovi". Allmovie.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Daniel Radcliffe to Grow 'Horns' for Supernatural Thriller". Screen Rant. March 9, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

References

- Konigsberg, Ira (1997). The Complete Film Dictionary (Second ed.). Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-670-10009-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Derry, Charles (2001). The Suspense Thriller: Films in the Shadow of Alfred Hitchcock. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1208-2.

- Frank, Alan (1997). Frank's 500: The Thriller Film Guide. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-2728-8.

- Hanich, Julian (2010). Cinematic Emotion in Horror Films and Thrillers: The Aesthetic Paradox of Pleasurable Fear. Routledge Advances in Film Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87139-6.

- Hicks, Neil D. (2002). Writing the Thriller Film: The Terror Within. Michael Wiese Productions. ISBN 978-0-941188-46-3.

- Indick, William (2006). Psycho Thrillers: Cinematic Explorations of the Mysteries of the Mind. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2371-2.

- Mesce, Bill (2007). Overkill: The Rise And Fall of Thriller Cinema. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2751-2.

- Rubin, Martin (1999). Thrillers. Genres in American Cinema. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58839-3.