Utica, New York

Utica, New York | |

|---|---|

City | |

|

Clockwise from top: Panorama of downtown from I-790, Looking south on Utica's Genesee Street, Utica Tower and harbor lock, Union Station, Utica Memorial Auditorium, Liberty Bell Corner, Stanley Theater | |

| Nickname(s): | |

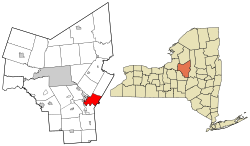

Location in Oneida County and New York | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Metro | Utica–Rome |

| County | Oneida |

| Land grant (village) | January 2, 1734[3] |

| Incorporated (village) | April 3, 1798[4] |

| Incorporated (city) | February 13, 1832[5] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Robert M. Palmieri (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 17.02 sq mi (44.1 km2) |

| • Land | 16.76 sq mi (43.4 km2) |

| • Water | 0.26 sq mi (0.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 456 ft (139 m) |

| Population (2010)[8] | |

• City | 62,235 |

• Estimate (2014[9]) | 61,332 |

| • Density | 3,818.1/sq mi (1,471.3/km2) |

| • Urban | 117,328 (U.S.: 268th)[7] |

| • Metro | 296,615 (U.S.: 163rd)[6][a] |

| Demonym | Utican |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 13501-13505, 13599 |

| Area code | 315 |

| FIPS code | 36-76540 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0968324[10] |

| Website | cityofutica.com |

Utica (pronounced /ˈjuːt[invalid input: 'ɨ']kə/ ) is a city in the Mohawk Valley and the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most-populous city in New York, its population was 62,235 in the 2010 U.S. census. Located on the Mohawk River at the foot of the Adirondack Mountains, Utica is approximately 90 miles (145 km) northwest of Albany and 45 miles (72 km) east of Syracuse. Although Utica and the neighboring city of Rome have their own metropolitan area, both cities are also represented and influenced by the commercial, educational and cultural characteristics of the Capital District and Syracuse metropolitan areas.

Formerly a river settlement inhabited by the Mohawk tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy, Utica attracted European-American settlers from New England during and after the American Revolution. In the 19th century, immigrants strengthened its position as a layover city between Albany and Syracuse on the Erie and Chenango Canals and the New York Central Railroad. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the city's infrastructure contributed to its success as a manufacturing center and defined its role as a worldwide hub for the textile industry. Utica's 20th-century political corruption and organized crime gave it the nicknames "Sin City",[11] and later, "the city that God forgot."[12]

Like other Rust Belt cities, Utica had an economic downturn beginning in the mid-20th century. The downturn consisted of industrial decline due to globalization and the closure of textile mills, population loss caused by the relocation of jobs and businesses to suburbs and to Syracuse, and poverty associated with socioeconomic stress and a decreased tax base. With its low cost of living, the city has become a melting pot for refugees from war-torn countries around the world, encouraging growth for its colleges and universities, cultural institutions and economy.

Etymology

Several theories exist about the history of the name "Utica".[13] Although surveyor Robert Harpur stated that he named the village,[13] the most accepted theory involves a 1798 meeting at Bagg's Tavern (a resting place for travelers passing through the village) where the name was picked from a hat holding 13 suggestions,[13][14] Utica being included because it is the name of a city of antiquity (several other upstate New York cities had adopted classical Mediterranean city names earlier, such as Troy, New York (1789) and Rome, New York (1796), or were to later, as with Syracuse, New York (1847).[15]

History

Iroquois natives and European settlement

Utica was established on the site of Old Fort Schuyler, built by English colonists for defense in 1758 during the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War against France.[4][16][17][18] Prior to construction of the fort, the Mohawk, Onondaga and Oneida tribes had occupied this area south of the Great Lakes region as early as 4000 BC.[19] The Mohawk were the largest and most powerful tribe in the eastern part of the Mohawk Valley. Colonists had a longstanding fur trade with them, in exchange for firearms and rum. The tribe's dominating presence in the region prevented the Province of New York from expanding past the middle of the Mohawk Valley until after the American Revolutionary War, when the Iroquois were forced to cede their lands as allies of the defeated British.[19]

The land housing Old Fort Schuyler was part of a 20,000-acre (80.94 km²) portion of marshland granted by King George II to New York governor William Cosby on January 2, 1734.[20] Since the fort was located near several trails (including the Great Indian Warpath), its position—on a bend at a shallow portion of the Mohawk River—made it an important fording point. The Mohawk called the bend Unundadages ("around the hill"), and the Mohawk word appears on the city's seal.[14][21][22]

During the American Revolution, border raids from British-allied Iroquois tribes harried the settlers on the frontier. George Washington ordered Sullivan's Expedition, Rangers, to enter Central New York and suppress the Iroquois threat. More than 40 Iroquois villages were destroyed and their winter stores, causing starvation.[14] In the aftermath of the war, numerous European-American settlers migrated into the state and this western region from New England,[23] especially Connecticut.[14]

In 1794 a state road, Genesee Road, was built from Utica west to the Genesee River. That year a contract was awarded to the Mohawk Turnpike and Bridge Company to extend the road northeast to Albany, and in 1798 it was extended.[4][24] The Seneca Turnpike was key to Utica's development, replacing a worn footpath with a paved road.[25] The village became a rest and supply area along the Mohawk River for goods and the many people moving through Western New York to and from the Great Lakes.[26][27]

The boundaries of the village of Utica were defined in an act passed by the New York State Legislature on April 3, 1798.[28] Utica expanded its borders in subsequent 1805 and 1817 charters. On April 5, 1805, the village's eastern and western boundaries were expanded,[29] and on April 7, 1817, Utica separated from Whitestown on its west.[4][30] After completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, the city's growth was stimulated again.

The municipal charter was passed by the state legislature on February 13, 1832.[4][5] The city's growth during the 19th century is indicated by the increase in its population; in 1845 the United States Census ranked Utica as the 29th-largest in the country (with 20,000 residents), more than the populations of Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland, respectively.[31][32] In the latter part of the century, Chicago became a boomtown based on resource extraction and processing from the Midwest, and as a railroad center.

Industry, trade, and slavery

Utica's location on the Erie and Chenango canals encouraged industrial development, allowing the transport of anthracite from northeastern Pennsylvania for local manufacturing and distribution.[33] Utica's economy centered around the manufacture of furniture, heavy machinery, textiles and lumber.[34] The combined effects of the Embargo Act of 1807 and local investment enabled further expansion of the textile industry.[35] Like other upstate New York cities, mills in Utica processed cotton from the Deep South, a slave society. Much of the New York economy was closely involved with slavery; in the antebellum period, half of New York's exports were related to cotton.

In addition to the canals, transport in Utica was bolstered by railroads running through the city. The first was the Mohawk and Hudson Rail Road, which became the Utica and Schenectady Railroad in 1833. Its 78-mile (126 km) connection between Schenectady and Utica was developed in 1836 from the right-of-way previously used by the Mohawk and Hudson River railway.[36][37] Later lines, such as the Syracuse and Utica Railroad, merged with the Utica and Schenectady to form the New York Central Railroad, which originated as a 20th-century forest railway in the Adirondacks.[38]

During the 1850s, Utica was known to aid more than 650 fugitive slaves; it played a major role as a station in the Underground Railroad. The city was on a slave escape route from the Southern Tier to Canada by way of Albany, Syracuse and Rochester.[39][40] The route, used by Harriet Tubman to travel to Buffalo,[41] guided slaves to pass through Utica on the New York Central Railroad right-of-way en route to Canada.[41] Utica was the locus for Methodist preacher Orange Scott's antislavery sermons during the 1830s and 1840s, and Scott formed an abolitionist group there in 1843.[40] Despite efforts by local abolitionists, pro-slavery riots and mobs, who wanted to protect the cotton mills, forced many abolitionist meetings to other cities.[42]

20th century to present

The early 20th century brought rail advances to Utica, with the New York Central electrifying 49 miles (79 km) of track from the city to Syracuse in 1907 for its West Shore interurban line.[43] In 1902, the Utica and Mohawk Valley Railway connected Rome to Little Falls with a 37.5-mile (60.4 km) electrified line through Utica.[44]

By the 1950s, Utica was known as "Sin City" because of the extent of its corruption at the hands of the Democratic Party political machine.[45][46][47][48] During the late 1920s, trucker Rufus Elefante rose to power[49][50] although he never ran for office.[51] Originally a Republican, Elefante's power was enhanced by support from New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.[52] Waves of Italian, Polish and Lebanese Maronite immigrants worked in the city's industries in the early part of the 20th century. Until the 1980s, organized crime had a strong role in the city.[48][53]

Strongly affected by the deindustrialization that took place in other Rust Belt cities, Utica suffered a major reduction in manufacturing activity during the second half of the 20th century. The 1954 opening of the New York State Thruway (which bypassed the city) and declines in activity on the Erie Canal and railroads throughout the United States also contributed to a poor local economy.[54] During the 1980s and 1990s, major employers such as General Electric and Lockheed Martin began to close plants in Utica and Syracuse.[55][56]

With city jobs moved to the towns and villages around Utica during the suburbanization of the postwar period. This led to the expansion of the nearby Town of New Hartford and the village of Whitesboro. Utica's lack of quality academic and educational choices, when compared to Syracuse under an hour away, contributed to its decline in local businesses and jobs as some economic activity moved to Syracuse during the 1990s.[57] Utica's population fell while population in the county increased, reflecting a statewide trend of decreasing urban populations outside New York City.[58] Residents who remain in the city struggle to handle poverty issues stemming from social and economic conditions caused partially by a smaller tax base; this adversely affects schools and public services.[59][60]

Despite the city's economic decline, it has benefited from a low cost of living,[61][62] attracting immigrants and refugees from around the world.[63][64][65] Among the new waves of immigrants are Muslim Bosnians and Buddhist Vietnamese. Further bolstering the city are its commercial, educational and cultural ties to the Capital District and Syracuse metropolitan areas.[66][67]

In 2010, Utica, the focus of local, regional and statewide economic-revitalization efforts,[68][69][70] developed its first comprehensive master plan in more than a half-century.[71][72]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, Utica has a total area of 17.02 square miles (44.1 km2)—16.76 square miles (43.4 km2) of land and 0.26 square miles (0.67 km2) (1.52 percent) of water.[73] The city is located at New York's geographic center, adjacent to the western border of Herkimer County, New York, and at the southwestern base of the Adirondack Mountains.[74] Utica and its suburbs are bound by the Allegheny Plateau in the south and the Adirondack Mountains in the north,[75] and the city is 456 feet (139 m) above sea level. The city is 90 miles (145 km) northwest of Albany[76] and 45 miles (72 km) east of Syracuse.[77]

Topography

The city's Mohawk name, Unundadages ("around the hill") refers to a bend in the Mohawk River that flows around the city's elevated position as seen from the Deerfield Hills in the north.[21] The Erie Canal and Mohawk River pass through northern Utica; northwest of downtown is the Utica Marsh, a group of cattail wetlands between the Erie Canal and Mohawk River (partially in the town of Marcy) with a variety of animals, plants and birds.[78][79] During the 1850s, plank roads were built through the marshland surrounding the city.[80] Utica's suburbs have more hills and cliffs than the city. Located where the Mohawk Valley forms a wide floodplain, the city has a generally sloping, flat topography.[74]

Cityscape

Utica's architecture features many styles that are also visible in comparable areas of Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse,[81] including Greek Revival, Italianate, French Renaissance,[82] Gothic Revival and Neoclassical. The modernist 1972 Utica State Office Building, at 17 floors and 227 feet (69 m), is the city's tallest.[83]

Early settlers and property owners contributed to the development of the city, and many families and individuals are remembered in street names.[84] Streets laid out when Utica was a village had more irregularities than those built later in the 19th and 20th centuries. As a result of the city's location (adjacent to the Mohawk River), many streets parallel the river, so they do not run strictly east-west or north–south. Remnants of Utica's early electric-rail systems can be seen in the West and South neighborhoods, where the rails were set into the streets.[21][85][86]

Neighborhoods

Utica's neighborhoods have historically been defined by their residents, allowing them to develop their own individuality. Racial and ethnic groups, social and economic separation and the development of infrastructure and new means of transportation have shaped neighborhoods, with groups shifting between them as a result.[32]

West Utica (or the West Side) was historically home to German, Irish and Polish immigrants. The Corn Hill neighborhood in the city center had a significant Jewish population.[87] East Utica (or the East Side) is a cultural and political center dominated by Italian immigrants.[88][89] North of downtown is the Triangle neighborhood, home to the city's African American and Jewish populations. Neighborhoods formerly dominated by one or more groups saw other groups arrive, such as Bosnians and Latin Americans in former Italian neighborhoods and the Welsh in Corn Hill.[32] Bagg Commemorative Park and Bagg's Square West (Utica's historic centers) are in the northeastern portion of downtown, with Genesee Street on the west and Oriskany Street on the south.[82]

Historic Places

The following are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:[90][91][92][93][94]

- Byington Mill (Frisbie & Stansfield Knitting Company)

- Calvary Episcopal Church

- Roscoe Conkling House

- Doyle Hardware Building

- First Baptist Church of Deerfield

- First Presbyterian Church

- Fort Schuyler Club Building

- Globe Woolen Company Mills

- Grace Church

- John C. Hieber Building

- Hurd & Fitzgerald Building

- Lower Genesee Street Historic District

- Memorial Church of the Holy Cross

- Millar-Wheeler House

- Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute

- New Century Club

- Rutger-Steuben Park Historic District

- St. Joseph's Church

- Stanley Theater

- Tabernacle Baptist Church

- Union Station

- U.S. Post Office, Court House and Custom House

- Utica Armory, Utica Daily Press Building

- Utica Parks and Parkway Historic District

- Utica Public Library

- Utica State Hospital

- Gen. John G. Weaver House

Climate

Utica has a continental climate with four distinct seasons and is in the humid continental climate (or warm-summer climate: Köppen Dfb)[95][96] zone, characterized by cold winters and temperate summers. Summer daytime temperatures range from 70–82 °F (21-28 °C), with an average winter daytime temperature below -3 °C (27 °F).[96] The city is in USDA plant hardiness zone 5a, and native vegetation can tolerate temperatures from -10 °F to -20 °F (-28.9 °C to -26.1 °C).[97]

Winters are cold and snowy; Utica receives lake-effect snow from Lake Erie and Lake Ontario.[98][99][100] Utica is colder on average than other Great Lakes cities because of its location in a valley and susceptibility to north winds;[101] temperatures in the single digits or below zero Fahrenheit are not uncommon on winter nights. Annual precipitation (based on a 30-year average from 1981–2010) is 42.1 inches (107 cm), falling on an average of 171 days.[102]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 2,972 | — | |

| 1830 | 8,323 | 180.0% | |

| 1840 | 12,782 | 53.6% | |

| 1850 | 17,565 | 37.4% | |

| 1860 | 22,529 | 28.3% | |

| 1870 | 28,804 | 27.9% | |

| 1880 | 33,914 | 17.7% | |

| 1890 | 44,007 | 29.8% | |

| 1900 | 56,383 | 28.1% | |

| 1910 | 74,419 | 32.0% | |

| 1920 | 94,156 | 26.5% | |

| 1930 | 101,740 | 8.1% | |

| 1940 | 100,518 | −1.2% | |

| 1950 | 100,489 | 0.0% | |

| 1960 | 100,410 | −0.1% | |

| 1970 | 91,611 | −8.8% | |

| 1980 | 75,632 | −17.4% | |

| 1990 | 68,637 | −9.2% | |

| 2000 | 60,523 | −11.8% | |

| 2010 | 62,235 | 2.8% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 61,332 | [103] | −1.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[104] | |||

Although Utica's population is predominantly European American, it has diversified since the 1990s. New immigrants and refugees have included Bosnians, displaced by the Bosnian War), Russians, Burmese, Vietnamese, and Latinos.[105] More than 15 languages are spoken in the city.[106] Utica has a low cost of living but its industrial and economic decline have posed difficulties for people trying to make a new start.[107]

The city is the tenth most populous in New York,[108] the seat of Oneida County,[109] and (with Schenectady) a focal point of the six-county Mohawk Valley region. According to a U.S. Census estimate, the Utica–Rome Metropolitan Statistical Area decreased in population from 299,397 in 2010 to 296,615 on July 1, 2014[108] and its population density was about 3,818 people per square mile (1,474/km²). Counties in the Mohawk Valley have a combined population of 622,133.[b]

In the 2010 United States Census, Utica's population was 62,235. Sixty-nine percent of the population was European American (of which 64.5 percent was non-Hispanic white), 15.3 percent was African American, and 0.3 percent was American Indian or Alaska Native. Asians were 7.2 percent of the city's population (3.5 percent Burmese, 1.5 percent Vietnamese, 0.7 percent Cambodian, 0.4 percent Indian, 0.2 percent Chinese, and 0.7 percent other Asian; numbers do not add up to 7.2 percent due to rounding),[110] Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders were 0.1 percent, and Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 10.5 percent (6.8 percent Puerto Rican, 1.5 percent Dominican, 0.4 percent Mexican, 0.3 percent Salvadoran, 0.2 percent Ecuadoran, 0.1 percent Cuban and 1.2 percent other Hispanic or Latino). Other races were 3.9 percent, and multiracial individuals made up four percent of the population.[111]

Median income for a Utica household was $30,818. Per capita income was $17,653, and 29.6 percent of the population were below the poverty threshold.[73]

| Racial composition | 2010[73] | 1990[112] | 1970[112] | 1950[112] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 69.0% | 86.7% | 94.1% | 98.4% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 64.5% | 84.8% | 91.2% | n/a |

| African American | 15.3% | 10.5% | 5.6% | 1.6% |

| American Indians and Alaska Natives | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | n/a |

| Asian | 7.2% | 1.1% | 0.1% | n/a |

| Other race | 3.9% | 1.5% | 0.1% | n/a |

| Two or more races | 4.0% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 10.5% | 3.4% | 0.9%[c] | n/a |

Economy

During the mid-19th century, Utica's canals and railroads supported industries producing furniture, locomotive headlights, steam gauges, firearms, textiles and lumber.[34][82] World War I sparked the growth of Savage Arms, which produced the Lewis gun for the British Army,[113] and the city prospered as one of the wealthiest per capita in the United States.[114]

In the early 20th century, the local textile industry began to decline, which had a significant impact on the local economy. The boll weevil adversely affected southern cotton crops in this period. During the late 1940s, air-conditioned mills opened in the southern United States, and jobs were lost as factories were moved south, where labor costs were lower because "right to work" laws weakened unions. Other industries also moved out of the city during a general restructuring in older industrial cities.[115] New industries to rise in the city were electronics manufacturing (led by companies such as General Electric, which produced transistor radios),[116] machinery and equipment, and food processing.[117]

The city struggled to make a transition to new industries. During the second half of the 20th century, the city's recessions were longer than the national average.[118] The exodus of defense companies (such as Lockheed Martin, formed from the merger of the Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta in 1995) and the electrical-manufacturing industry played a major role in Utica's recent economic distress.[118] From 1975 to 2001, the city's economic growth rate was similar to that of Buffalo, while other upstate New York cities such as Rochester and Binghamton outperformed both.[118]

In the early 21st century, the Mohawk Valley economy is based on logistics, industrial processes, machinery, and industrial services.[119] In Rome, the former Griffiss Air Force Base has remained a regional employer as a technology center. The Turning Stone Resort & Casino in Verona is a tourist destination, with a number of expansions during the 1990s and 2000s.[120]

Utica's larger employers include the ConMed Corporation (a surgical-device and orthotics manufacturer)[121] and Faxton St. Luke's Healthcare, the city's primary health care system.[122]

Construction, such as the North-South Arterial Highway project, supports the public-sector job market.[123] Although passenger and commercial traffic on the Erie Canal has declined greatly since the 19th century, the barge canal still allows heavy cargo to travel through Utica at low cost, bypassing the New York State Thruway and providing intermodal freight transport with the railroads.[124]

Law, government, and politics

Template:Utica crimebox Democrat Robert M. Palmieri, elected in 2011, is Utica's current mayor.[125][126] The common council consists of 10 members, six of whom are elected from single-member districts. The other four, including its president, are elected at-large.[127] The council has eight standing committees for issues including transportation, education, finance and public safety.[128] There is a relative balance between the Democratic and Republican parties, a change from the predominantly single-party politics of the 20th century.[129] Throughout the 1950s, Democrats ran the city council and mayoralty.[130]

Utica is in New York's 22nd congressional district, which has been represented by Republican Richard L. Hanna since 2013. The city is served by the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York, with offices in the Alexander Pirnie Federal Building.[131]

According to the comptroller's office, Utica's governmental expenses totaled $79.3 million in 2014 (a net increase of $940,000 from the previous year).[132] The 2015–16 budget proposes general-fund spending of $66.3 million.[133] City taxes collected in 2014 were $25,972,930, with a tax rate per thousand of $25.24.[133]

According to the city's police department, there were six murders, 125 robberies, 22 rapes, and 237 assaults in 2014 (an increase from the previous year, representing a violent-crime rate of 0.6 percent). There were 432 burglaries, 1,845 larcenies and 107 motor-vehicle thefts (a decrease from 2013, representing a property-crime rate of 3.8 percent). Compared to other cities in New York, Utica's crime rate is generally low.[134][135] The Utica Police Department patrols the city, and law enforcement is also under the jurisdiction of the Oneida County Sheriff's Office and the New York State Police.[136] The Utica Fire Department coordinates four engines, two truck companies, and rescue, HAZMAT and medical operations with a 123-person crew.[137]

Culture

Utica's position in the northeastern United States has allowed the blending of cultures and traditions. The city shares characteristics with other cities in Central New York, including its dialect (Inland Northern American English, also present in other Rust Belt cities such as Buffalo, Elmira and Erie, Pennsylvania).[138]

Utica shares a cuisine with the mid-Atlantic states, with local and regional influences. The city's melting pot of immigrant and refugee cuisines,[139] including Dutch, Italian, German, Irish and Bosnian,[63] has introduced dishes such as ćevapi and pasticciotti[d] to the community.[142][143] Utica staple foods include chicken riggies,[144] Utica greens,[145] half-moons,[146][147] mushroom stew,[148] and tomato pie.[149] Other popular dishes are pierogi, penne alla vodka, and sausage and peppers.[150][151] Utica has long had ties to the brewing industry. The family-owned Matt Brewing Company resisted the bankruptcies and plant closings that came with the industry consolidation under a few national brands. As of 2012, it was ranked the 15th-largest brewery by sales in the United States.[152][153]

The annual 15-kilometre (9.3 mi) Boilermaker Road Race, organized by the city in conjunction with the National Distance Running Hall of Fame, attracts runners from the region and around the world, including Kenya and Romania.[154][155] The Children's Museum of Natural History, Science and Technology, next to Union Station, opened in 1963. In 2002 the museum partnered with NASA, featuring exhibits and events from the agency.[156][157] The Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, founded in 1919, features a PrattMWP program in cooperation with the Pratt Institute, and permanent collections and rotating exhibits.[158]

The Utica Psychiatric Center is housed in a Greek Revival structure that was an insane asylum, and the birthplace of the Utica crib—a restraining device frequently used at the asylum from the mid-19th century to 1887.[13][159][160][161] The Stanley Center for the Arts, a mid-sized concert and performance venue, was designed by Thomas W. Lamb in 1928 and today features theatrical and musical performances by local and touring groups.[162] The Hotel Utica, designed by Esenwein & Johnson in 1912, became a nursing and residential-care facility during the 1970s.[163][164] Notable guests had included Franklin D. Roosevelt, Judy Garland and Bobby Darin. It was restored as a hotel in 2001.[164][165]

Sports

Utica is home to the Utica Comets, a team affiliated with the National Hockey League's Vancouver Canucks. Formerly the Peoria Rivermen, the team moved to Utica and began playing in the American Hockey League during the 2013–14 season.[166][167] The 3,815-seat Utica Memorial Auditorium, which opened in 1960, is home to the Comets and the Utica College Pioneers. The Utica Devils played in the AHL from 1987 to 1993, and the Utica Bulldogs (1993–94), Utica Blizzard (1994–97), and Mohawk Valley Prowlers (1998–2001) were members of the United Hockey League (UHL).[168]

The city was home to the Utica Blue Sox (1939–2001), a New York–Penn League baseball team also affiliated with the Toronto Blue Jays and, later, the Miami Marlins. Other former baseball teams included the Utica Asylums (1900) and the Boston Braves-affiliated Utica Braves (1939–42).[169]

Area collegiate teams

| School | Location | Nickname | Colors | Association | Conference | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUNY Polytechnic Institute | Marcy | Wildcats | Blue and gold | NCAA Division III | NEAC | [170] |

| Hamilton College | Clinton | Continentals | Buff and blue | NCAA Division III | NESCAC | [171] |

| Utica College | Utica | Pioneers | Navy and orange | NCAA Division III | Empire 8 | [172] |

| Mohawk Valley Community College | Utica, Rome | Hawks | Forest green and white | NJCAA | Region III | [173] |

| Herkimer County Community College | Herkimer | Generals | Hunter green and gold | NJCAA | Region III | [174] |

Parks and recreation

Utica's parks system consists of 677 acres (274 ha) of parks and recreation centers; most of the city's parks have community centers and swimming pools.[175] Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who designed New York City's Central Park and Delaware Park in Buffalo, designed the Utica Parks and Parkway Historic District.[176] Olmsted also designed Memorial Parkway, a 4-mile (6.4 km) tree-lined boulevard connecting the district's parks and encircling the city's southern neighborhoods.[177][178] The district includes Roscoe Conkling Park, the 62-acre F.T. Proctor Park, the Parkway, and T.R. Proctor Park.[179][180]

The city's municipal golf course, Valley View (designed by golf-course architect Robert Trent Jones), is in the southern part of the city near the town of New Hartford.[175] The Utica Zoo and the Val Bialas Ski Chalet, an urban ski slope featuring skiing, snowboarding, outdoor skating, and tubing, are also in south Utica in Roscoe Conkling Park.[181] Smaller neighborhood parks in the district include Addison Miller Park, Chancellor Park, Seymour Park, and Wankel Park.[182]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Griffiss International Airport in Rome primarily serves military and general aviation, and Syracuse Hancock International Airport and Albany International Airport provide regional, domestic, and international passenger air travel in the Utica–Rome Metropolitan Area.[183] Amtrak's Empire, Maple Leaf, and Lake Shore Limited trains stop at Utica's Union Station. Bus service is provided by the Central New York Regional Transportation Authority (CENTRO), a Syracuse public transport operator which runs 12 lines in Utica and has a downtown hub.[184] Intercity bus service is provided by Greyhound Lines and the Birnie Bus Company, with weekday and Saturday service to Syracuse;[185] both stop at Union Station.[186][187]

During the 1960s and 1970s, New York state planners envisioned a system of arterial roads in Utica that would include connections to Binghamton and Interstate 81.[188] Due to community opposition,[189] only parts of the highway project were completed, including the North–South Arterial Highway running west of the city.[188][190] Six New York State highways, one three-digit interstate highway, and one two-digit interstate highway pass through Utica. New York State Route 49 and State Route 840 are east–west expressways running along Utica's northern and southern borders, respectively, and the eastern terminus of each is in the city. New York State Route 5 and its alternate routes—State Route 5S and State Route 5A—are east–west roads and expressways that pass through Utica. The western terminus of Route 5S and the eastern terminus of Route 5A are both in the city. With Route 5 and Interstate 790 (an auxiliary highway of Interstate 90), New York State Route 12 and State Route 8 form the North–South Arterial Highway.[191]

Utilities

Electricity in Utica is provided by National Grid plc, a British energy corporation that acquired the city's former electricity provider, Niagara Mohawk, in 2002.[192] Utica is near the crossroads of major electrical-transmission lines,[193] with substations in the town of Marcy. An expansion project by the New York Power Authority, National Grid, Consolidated Edison, and New York State Electric and Gas (NYSEG) is planned.[194][195] In 2009 city businesses (including Utica College and St. Luke's Medical Center) developed a microgrid, and in 2012 the Utica City Council explored the possibility of a public, city-owned power company.[196][197][198] Utica's natural gas is provided by National Grid[199] and NYSEG.[200][201]

Municipal solid waste is collected and disposed of weekly by the Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority,[202] a public-benefit corporation that coordinates single-stream recycling, waste reduction, composting, and the disposal of hazardous materials and demolition debris.[203] Utica's wastewater is treated by the Mohawk Valley Water Authority, with a capacity of 32 million gallons per day.[204][205] Treated water is tested for impurities including pathogens, nitrates, and nitrites.[204] Utica's drinking water comes from the stream-fed Hinckley Reservoir in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains,[205] with 700 miles (1,100 km) of piping throughout the city.[206]

Health care

Primary health care in Utica is provided by the Mohawk Valley Health System, a nonprofit organization that operates Faxton St. Luke's Healthcare and St. Elizabeth Medical Center.[207] The St. Luke's and Faxton hospitals have a total of 370 acute and 202 long-term beds, and St. Elizabeth Medical Center has 201 acute-care beds.[208] St. Luke's and Faxton are surgical centers, and St. Elizabeth is a trauma and surgical center.[207] The Mohawk Valley Health System prefers to construct a new hospital in Downtown Utica by 2021, consolidating operations at the existing hospitals.[209]

Education

Like Ithaca and Syracuse, Utica has a mix of public and private colleges and universities; three state colleges and four private colleges are in the Utica–Rome metropolitan area. SUNY Polytechnic Institute, on an 850-acre campus in North Utica and Marcy, has over 2,000 students[210] and is one of eight technology colleges and 14 doctorate-granting universities of the State University of New York (SUNY).[211][212] Mohawk Valley Community College is the largest college between Syracuse and Albany with nearly 7,000 students,[213] and an Empire State College location serves Utica and Rome.[214]

Formerly a satellite campus of Syracuse University, Utica College is a four-year private liberal arts college with over 3,000 students.[215] Established in 1904, St. Elizabeth College of Nursing partners with regional institutions to grant nursing degrees.[216] Pratt Institute offers a local two-year fine-arts course,[217] and the Utica School of Commerce has business-related programs at its Central New York locations.[218]

The Utica City School District had an enrollment of nearly 10,000 in 2012[219] and is the most racially diverse school district in Upstate New York.[220] District schools include Thomas R. Proctor High School, James H. Donovan Middle School, and 12 elementary schools. Utica's original public high school, the Utica Free Academy, closed in 1987.[221] The city is also home to Notre Dame Junior Senior High School, a small Catholic high school founded in 1959 by the Xaverian Brothers.[222]

Media

Utica is served by three stations affiliated with major television networks: WKTV (NBC on DT1/CBS on DT2/CW on DT3),[223] WUTR (ABC), and WFXV (Fox). PBS member station WCNY-TV in Syracuse operates translator W22DO-D on analog channel 22 and digital channel 24. Several low-power television stations, such as WPNY-LP (MyNetworkTV), also broadcast in the area. Cable television viewers are served by the Syracuse office of Time Warner Cable, which offers a local news service, a local sports channel, and public-access channels.[224] Dish Network and DirecTV provide satellite television customers with local broadcast channels.[225][226]

Utica's main daily newspaper is the Observer-Dispatch; the Utica Phoenix, established in 2002, is an alternative.[227] The city has 26 FM radio stations and nine AM stations. Major station owners in the area include Townsquare Media and Galaxy Communications. In addition to minor popular-culture references,[228][229][230][231] Slap Shot (1977) was partially filmed in Utica, and the city has been featured on the TV series The Office.[230][232][233]

The Mid York Library System serves Utica and is chartered by the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York. The library system operates 43 libraries[234] (including the Utica Public Library) in Oneida, Herkimer and Madison counties.[235]

Notable people

See also

- Lower Genesee Street Historic District

- Utica Shale – a geological formation named for Utica

- Timeline of town creation in Central New York

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Estimated MSA rank as of July 1, 2014.

- ^ Calculated from the total populations of Oneida, Herkimer, Schenectady, Otsego, Fulton, and Montgomery counties as of the 2010 census.

- ^ Population estimate from a 15-percent sample

- ^ Locally known as "pusties"[140][141]

References

- ^ Mittel Jr., David A. (June 4, 2008). "The city that God Forgot". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 7, 2008.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 5, 2008 suggested (help) - ^ Bottini, Joseph L.; Davis, James L. (2007). Utica. Arcadia Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7385-5496-9.

- ^ Bagg 1892, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Ripley, George, ed. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia. Vol. 16 (1879 ed.). D. Appleton & Company – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: More than one of|editor1-first=and|editor-first=specified (help); More than one of|editor1-last=and|editor-last=specified (help); More than one of|editor1-link=and|editor-link=specified (help) - ^ a b Bagg 1892, p. 199.

- ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014" (CSV). 2014 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Census Urban Area List". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. June 9, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ^ "Feature Detail Report for: Utica". United States Geological Survey. 23 January 1980. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Schneider, Meg. New York Yesterday & Today. Voyageur Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-6167-3126-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mittell Jr., David A. (June 8, 2008). "Visitor takes a lonely walk through Utica". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ a b c d Czarnota, Lorna (2014). "Utica: Beer and Insanity". Native American & Pioneer Sites of Upstate New York: Westward Trails from Albany to Buffalo. The History Press. pp. 77–81. ISBN 978-1-6258-4776-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Thomas 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Natalie (January 10, 2006). "What's in a Name No.2: The Origins of Classical Place Names in Upstate New York". York Staters. Retrieved November 16, 2015. [better source needed]

- ^ Bagg 1892, p. 3.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 2.

- ^ Bagg 1892, p. 21.

- ^ a b Thomas 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Bagg 1892, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c Childs 1900, p. 134.

- ^ Czarnota, Lorna (2014-04-08). "Utica: Beer and Insanity". Native American & Pioneer Sites of Upstate New York: Westward Trails from Albany to Buffalo. The History Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-6258-4776-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Childs 1900, p. 1.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 52.

- ^ Hulbert, Archer Butler; Hall, James; Wallcut, Thomas; Bigelow, Timothy; Halsey, Francis Whiting; Dickens, Charles; Murray, Sir Charles Augustus (1904). Pioneer Roads and Experiences of Travelers. A. H. Clark Company. pp. 99–108. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 7.

- ^ Przybycien, F. E. (1976). Utica: A City Worth Saving. Dodge-Graphic Press, Inc.

- ^ Bagg 1892, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bagg 1892, p. 89.

- ^ Bagg 1892, p. 131.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Thomas 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Reports and Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States, Volume 59. Harvard University: L.K. Strouse, United States Interstate Commerce Commission. 1921. p. 142.

- ^ a b Childs 1900, p. 25.

- ^ Cookinham, H. J. (1912). History of Oneida County, New York: from 1700 to the present time. New York Public Library: Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company.

- ^ Childs 1900, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Starr, Timothy (2012). Railroad Wars of New York State. The History Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-6094-9727-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Gove, Bill (2006). Logging Railroads of the Adirondacks. Syracuse University Press. pp. 71–75. ISBN 978-0-8156-0794-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Calarco, Tom (2011-02-23). The Underground Railroad in the Adirondack Region. McFarland. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7864-8740-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Switala 2006, p. 80.

- ^ a b Switala 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Switala 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Edwards, Evelyn R. (2007-01-24). Around Utica. Arcadia Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4396-1852-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hilton, George W.; Due, John Fitzgerald (2000-01-01). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780804740142.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Annette apologizes for calling Utica 'sin city of the East'". Lakeland Ledger. Vol. 78, no. 5. October 27, 1983. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Lentricchia, Frank (4 March 2013). "Seeking the truth in Utica". Philly.com. Reviewed by Michael Harrington. Philadelphia Media Network. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Benedetto, Richard (2006). Politicians are People, Too. University Press of America. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7618-3422-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Webster, Dennis (2012). Wicked Mohawk Valley. The History Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-6094-9390-5.

- ^ Hartman, K. E. (14 August 2006). "Exploring the Mohawk Valley: Selected Print Resources" (PDF). Mohawk Valley Community College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Herbers, John (1989-03-26). "The Region; Tales From Elsewhere: Entering the New Era Of Municipal Rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- ^ Cardarelli, Malio J. (29 August 2010). "Guest view: There's no denying that 'Rufie' left his mark on Utica". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Croniser, Rebecca (14 September 2008). "Utica's organized crime revisited". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ Thomas 2003, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, p. 66.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Hevesi, Alan G. "Population Trends in New York State's Cities" (PDF). Division of Local Government Services & Economic Development. Office of the New York State Comptroller. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Dooling, Sarah; Simon, Gregory (2012). Cities, Nature and Development: The Politics and Production of Urban Vulnerabilities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 165–181. ISBN 978-1-4094-0831-4.

- ^ Clukey, Keshia (December 28, 2013). "Utica schools have highest poverty rate in Upstate NY". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-08-24.

- ^ Ledbetter, Carly (November 15, 2014). "10 Most Affordable Housing Markets In America". Huffington Post. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Weir, Robert E. (2013). Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-5988-4719-2.

- ^ a b Hartman, Susan (10 August 2014). "A New Life for Refugees, and the City They Adopted". New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Coughlin, Reed; Owens-Manley, Judith (2006). Bosnian Refugees in America: New Communities, New Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-3872-5154-7.

- ^ Brody, Leslie (2015-01-21). "Small Cities Fight for More School Aid From New York State". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ "Granite Broadcasting Corporation | Syracuse". Granite Broadcasting Corporation. Granite Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Odato, James M. (March 19, 2014). "SUNY's CNSE to merge with SUNY-IT". Times Union. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Governor Cuomo Announces 'Nano Utica' $1.5 Billion Public-Private Investment That Will Make the Mohawk Valley New York's Next Major Hub of Nanotech Research". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. New York State. October 10, 2013. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Cuomo visits Lake Placid, Utica to talk upstate development". WIVB.com. Associated Press. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Cooper, Elizabeth (February 17, 2015). "Cuomo won't budge on $1.5 billion economic development competition". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Thomas, Brian (8 February 2010). "City of Utica Master Plan Accomplishments / 2.8.10". City of Utica Master Plan. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Miner, Dan (12 July 2010). "Utica master plan: 'Play ball!' at Harbor Point?". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ a b c "Utica (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ a b Hislop, Codman (1948). The Mohawk. Syracuse University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8156-2472-1.

- ^ Hudson, John C. (2002). Across This Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1.

- ^ "Utica, NY to Albany, NY". Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 5.

- ^ "Utica Marsh Wildlife Management Area Overview". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Utica Marsh" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 55.

- ^ Bottini & Davis 2007, p. ix. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBottiniDavis2007 (help)

- ^ a b c Writers' Program. New York (1974). New York: A Guide to the Empire State. North American Book Dist LLC. pp. 353–355. ISBN 978-0-4030-2151-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "New York State Office Building, Utica". SkyscraperPage.com. Skyscraper Source Media. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 60.

- ^ Childs 1900, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 130.

- ^ Kohn, Solomon Joshua (1959). The Jewish community of Utica, New York, 1847-1948. American Jewish Historical Society. p. 130. OCLC 304259.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bean, Philip A. (2004). La Colonia: Italian Life and Politics in Utica, New York, 1860-1960. Utica College, Ethnic Heritage Studies Center. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-9660-3630-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Tamburri, Anthony Julian; Giordano, Paolo; Gardaphe, Fred L. (2000). From the Margin: Writings in Italian Americana. Purdue University Press. pp. 386–390. ISBN 978-1-5575-3152-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 9/07/10 THROUGH 9/10/10. National Park Service. 2010-09-17.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 1/03/12 through 1/06/12. National Park Service. 2012-01-13.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 9/14/15 through 9/18/15. National Park Service. 2015-09-25.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 1/04/16 through 1/08/16. National Park Service. 2016-01-15.

- ^ Kottek, Marcus; Greiser, Jürgen; et al. (June 2006). "World Map of Köppen–Geiger Climate Classification". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3). E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: 261. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- ^ a b "Utica, New York Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2012. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ Catie, O'Toole (5 January 2015). "Weather: 6 inches to nearly 2 feet of lake-effect snow possible in parts of CNY". Syracuse.com. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (2000). Air Apparent: How Meteorologists Learned to Map, Predict, and Dramatize Weather. University of Chicago Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-2265-3423-7.

- ^ Karmosky, Christopher (2007). Synoptic Climatology of Snowfall in the Northeastern United States: an Analysis of Snowfall Amounts from Diverse Synoptic Weather Types. University of Delaware. Department of Geography. ProQuest. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-5493-8718-3.

- ^ Childs 1900, p. 136.

- ^ "Utica, New York Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Clarridge, Emerson (July 11, 2010). "Mayor Roefaro to speak at Bosnian commemoration event in Syracuse". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Utica, New York". Modern Language Association. 2000. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ Ackerman, Bryan; Cooper, Elizabeth (April 1, 2009). "Area at bottom of Forbes list for business". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-08-24.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014 - 2014 Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Residents | Oneida County, NY". ocgov.net. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ "American FactFinder". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010". American FactFinder. U.S. Census. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "New York - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Savage Arms History". Savage Arms. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 117.

- ^ "Utica | Buildings | Emporis". Emporis. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ a b c "The Regional Economy of Upstate New York" (PDF). New York Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ "Mohawk Valley | START-UP NY". wayback.archive.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bottini & Davis 2007, p. x. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBottiniDavis2007 (help)

- ^ Gerould, S. Alexander (January 4, 2015). "DEC has eye on contamination at ConMed site". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ "CONMED Corporation News". The New York Times. 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Miner, Dan (3 May 2012). "DOT unveils accelerated time frame for Arterial project". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Goodban Belt, LLC (May 2010). "New York State Canal System, Modern Freight-Way" (PDF). New York State Canal Corporation. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ "Mayor's Office". City of Utica. Retrieved 2015-05-04.

- ^ Miner, Dan (November 17, 2011). "Palmieri wins Utica mayoral election". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Common Council". City of Utica. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ "Standing Committees". City of Utica. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ Thomas 2003, pp. 145–149.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 37.

- ^ "Utica | Northern District of New York | United States District Court". United States Court, Northern District of New York. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "City of Utica, Financial Statements and Required Reports Under OMB Circular A-133 as of March 31, 2014" (PDF). City of Utica. City of Utica. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ a b "2015-2016 Board of E & A Approved Budget" (PDF). City of Utica. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Sperling, Bert; Sander, Peter J. (2007-05-07). Cities Ranked & Rated: More Than 400 Metropolitan Areas Evaluated in the U.S. and Canada. John Wiley & Sons. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-4700-6864-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Crime, Arrest and Firearm Activity Report" (PDF). Division of Criminal Justice Services. New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (published March 6, 2015). January 31, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ^ "Law Enforcement Division - Oneida County Sheriff". Oneida County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ "Fire Department". City of Utica. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ Bartelma, Katy; Inc, Let's Go (2004-12-13). Let's Go 2005 USA: With Coverage of Canada. St. Martin's Press. p. 642. ISBN 978-0-3123-3557-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ Santos, Fernanda (21 October 2006). "Where Young Refugees Find a Place to Fit In". The New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Quality of Life". City of Utica. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ Nadeau, Mary (September 11, 2008). "A bright outlook on life". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- ^ Miltner, Karen (20 June 2010). "From riggies to cevapi, immigrants have shaped Utica's food scene". Democrat and Chronicle. Gannett. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "New York State". Insight Guides: USA on the Road. Insight Guides. Apa Publications (UK) Limited. 2013-02-25. ISBN 978-1-7800-5632-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Monaski, Jeff (6 June 2013). "Utica Native Shares Chicken Riggies Recipe With Taste Of Home Magazine". WIBX 950AM. Townsquare Media. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Baber, Cassaundra (11 January 2010). "Next Food Network star: Utica greens". Utica Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Levine, Ed (15 January 2008). "The Best Black and White Cookies? Half-Moons? Amerikaners?". New York Serious Eats. Serious Eats. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Hubbell, Matt (16 April 2015). "Are Utica's Halfmoon Cookies 'Today Show' Bound?!". lite98.7. Townsquare Media. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Mushroom stew: Investigating a Utica classic". Table Hopping. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ^ Russell, Tina (6 August 2014). "O'Scugnizzo Pizzeria: A slice of Utica's history turns 100". Utica Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "Visitors". City of Utica. Food. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ "Quality of Life". www.cityofutica.com. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- ^ "F.X. Matt Brewing Co. / Saranac - Brew Central". BrewCentralNY.com. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Brewers Association Releases Top 50 Breweries of 2012; Top 50 Overall U.S. Brewing Companies (Based on 2012 beer sales volume)". Boulder, CO: Brewers Association. April 10, 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-09-21. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Moses, Sarah. "Boilermaker Road Race makes changes to registration process for 2015". Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Braine, Bill (November 2007). Runner's World. 11. Vol. 42. Rodale, Inc. pp. 119–120. ISSN 0897-1706.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Sharp, Debbie (6 July 2005). "Opening Set for NASA Exhibits at Utica Children's Museum". NASA. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "The Children's Museum of History, Natural History, Science & Technology". City of Utica. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "PrattMWP, Pratt Institute's Utica, NY campus: A Great Choice for Many Art Students". PrattMWP College of Art and Design. Munson Williams Proctor Art Institute. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Burns, Stanley B. "19th and 20th century psychiatry: 22 rare photos". CBS News. CBS. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Roth, Amy Neff (26 April 2013). "'Old Main' played important role in history of psychiatry". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "The Straightjacket and Utica Crib: Diagnostik". University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. The University of Iowa. 2 Nov 2001. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ "About » Stanley Center For The Arts". Stanley Center for the Arts. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Bottini & Davis 2007, p. 13. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBottiniDavis2007 (help)

- ^ a b "Hotel Utica – A History". Hotel Utica. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Tucker, Libby (2013). "New York's Haunted Bars". Voices. 39 (Spring–Summer). Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Utica Comets to join AHL in 2013-14". TheAHL.com. American Hockey League. June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Introducing the Utica Comets of the AHL | ProHockeyTalk". wayback.archive.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "United Hockey League history and statistics at hockeydb.com". hockeydb.com. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Worth, Richard (2013-02-26). Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, 1869-2011. McFarland. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-7864-6844-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Overview". SUNY Poly Athletics. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Overview". Hamilton College. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Sports Information". Utica College Pioneers. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Mohawk Valley Community College". NJCAA. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "About The Herkimer Generals Athletic Program". www.herkimergenerals.com. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- ^ a b "Parks and Recreation". City of Utica. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Parks & Open Spaces". www.cityofutica.com. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- ^ Vincent (2007-01-01). Lin Smith, Vincent; Waller, Sydney (eds.). Sculpture Space: The Book : for the Artists and Individuals who are Part of the Sculpture Space Story. Thomas Piché, Sculpture Space (Studio). Sculpture Space, Incorporated. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-9795-9690-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Memorial Parkway | Explore Our Parks | Central New York Conservancy | Mohawk Valley". Central New York Conservancy. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ "Proctor Park". Oneida County Historical Society. Oneida County Historical Society. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Explore Our Parks in Utica, New York". Central New York Conservancy. Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- ^ Pitarresi, John (22 December 2012). "Val Bialas Sports Center: Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ "Parks & Open Spaces". City of Utica. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 156.

- ^ "Centro Utica". Centro. April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Central New York - Weekday Line Runs" (PDF). Birnie Bus Service, Inc. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ "Greyhound.com, Utica, NY". Greyhound. Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ "Central New York - Saturday Line Runs" (PDF). Birnie Bus Service, Inc. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ a b Thomas 2003, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 114.

- ^ Report on State arterial route plans in the Utica urban area. New York (State). Dept. of Public Works. University of Michigan: Department of Public Works. 1950.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ "National Grid - 2002 News Releases". nationalgridus.com. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "New York Transco Transmission Projects". New York State Electric & Gas. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "Major Transmission Facilities Included In and Excluded From the Transmission Revenue Requirement" (PDF). New York Power Authority. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Kemble, William J. (16 November 2013). "Proposed power line through Mid-Hudson region stirs concerns". The Daily Freeman. 21st Century Media. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ Roth, Amy (September 18, 2014). "Mini electric stations, such as at Faxton St. Luke's, being touted". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ Zeman, F. (2012-09-11). Metropolitan Sustainability: Understanding and Improving the Urban Environment. Elsevier. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-8570-9646-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Miner, Dan (26 January 2012). "Utica forming panel to study possibility of new power system". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "Proceeding To Examine Policies Regarding the Expansion of Natural Gas Service Case 12-G-0297" (PDF). New York State Public Service Commission. National Grid. January 9, 2013. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ Handelman, David. "National Grid requests $400,000 from city". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "Service Area". New York State Electric & Gas. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "City of Utica Garbage & Recycling: Collection & Disposal Information" (PDF). Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "About Us » Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority". Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ a b "Water Quality". Mohawk Valley Water Authority. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Water Quality Report 2014" (PDF). Mohawk Valley Water Authority. 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Cooper, Elizabeth (September 27, 2015). "Region boasts plentiful, clean water". Observer Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ^ a b "About the Mohawk Valley Health System". Mohawk Valley Health System. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ "Fact Sheet". Mohawk Valley Health System. Retrieved 2015-04-21.

- ^ Roth, Amy Neff (September 23, 2015). "Downtown first choice for new hospital". Observer Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- ^ "Campuses / SUNY Polytechnic Institute (formerly SUNYIT)". The State University of New York. The State University of New York. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "Contact Information for SUNY Technology Colleges". OPEN SUNY. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "SUNY Vice Presidents for Research - RF for SUNY". SUNY Research Foundation. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "About MVCC". Mohawk Valley Community College. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "Utica | Central New York | SUNY Empire State College". www.esc.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ "About Utica College". Utica College. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ "History | St. Elizabeth College of Nursing | Utica, NY". St. Elizabeth College of Nursing. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "Pratt BFA Degrees | Top Ranked Design & Fine Arts Programs » PrattMWP". PrattMWP College of Art and Design. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "Utica School of Commerce". Utica School of Commerce. Retrieved 2015-04-24.

- ^ "Utica City School District". Federal Education Budget Project. New America Foundation. 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ Scott Thomas, G (June 25, 2015). "Utica scores highest in Upstate New York for racial diversity in public schools". Buffalo Business First. American City Business Journals. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Tracey, Sarah (5 April 2014). "UFA to celebrate 200 years of memories, milestones". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ^ NDHS. "School History". Notre Dame High School website. Archived from the original on 2007-04-16.

- ^ "WKTV bringing CBS affiliation to Utica". WKTV. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ "About TWC News". TWC News. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Dish Network to Become First Pay-TV Provider to Offer Local Broadcast Channels in All 210 Local Television Markets in the United States" (PDF). Dish Network - Investor Relations. Comtex News Network. May 27, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Get DirecTV in Utica". DirecTV. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Geruntino, Gino (28 December 2011). "Utica Phoenix Gains Official Newspaper Designation". WIBX950. Townsquare Media. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 121.

- ^ a b Lynn, Naomi (6 January 2015). "Utica Gets Plenty of Attention In The Entertainment World: These TV Shows And Movies Prove Utica Is More Popular Than You Think". lite98.7. Townsquare Media. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1956). Howl and Other Poems. City Light Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8728-6017-9.

- ^ Herbert, Geoff (2013-09-18). "Night Ranger, Gordie Howe and 'Slap Shot' stars coming to Utica Comets' first home game". Syracuse.com. Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- ^ Fran Perritano (May 28, 2010). "'Hanson Brothers' will return to Utica Aud". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ "Library Information". Mid York Library System. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "About MYLS". Mid York Library System. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Bagg, M. M. (1892). Memorial History of Utica, N.Y.: From Its Settlement to the Present Time. Cornell University Library: D. Mason & Co. Publishers. OCLC 1837599.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bottini, Joseph P.; Davis, James L. (2007). Utica. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5496-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Childs, L. C. (1900). Outline History of Utica and Vicinity. New Century Club, Utica, New York. OCLC 1558992.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Switala, William J. (2006). Underground Railroad in New Jersey and New York. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3258-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Alexander R. (2003). In Gotham's Shadow. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5595-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Alexander R.; Smith, Polly J. (2009). Upstate Down: Thinking about New York and Its Discontents. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4500-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Bartholomew, Harland (1921). A Preliminary Report on Major Streets, Utica, New York. Willard Press. OCLC 682139143.

- Ferris, T. Harvey (1913). Utica, the Heart of the Empire State. Library of Congress. ASIN B00486TJ2C.

- Kobryn, Nancy (1995). Guts and Glory, Tragedy and Triumph: the Rufus P. Elefante Story. Steffen Pub. OCLC 40756638.

- Pula, James S. (1994). Ethnic Utica. Ethnic Heritage Studies Center, Utica College of Syracuse University. ISBN 978-0-9668-1785-0.

- Utica Public Library (1932). A Bibliography of the History and Life of Utica; a Centennial Contribution. Goodenow Print. Co. OCLC 1074083.

External links

- NYPL Digital Gallery, Items related to Utica, NY

- Library of Congress, Prints & Photos Division, Items related to Utica, NY

- SkyscraperPage, Diagram of skyscrapers in Utica, NY

Utica travel guide from Wikivoyage

Utica travel guide from Wikivoyage