Prehistoric Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt/ Predynastic Egypt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Artifacts of Egypt from the Prehistoric period, from 4400 to 3100 BC. First row from top left: a Badarian ivory figurine, a Naqada jar, a Bat figurine. Second row: a diorite vase, a flint knife, a cosmetic palette. | |||||||

| |||||||

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt was the period of time starting at the first human settlement and ending at the First Dynasty of Egypt around 3100 BC.

At the end of prehistory, "Predynastic Egypt" is traditionally defined as the period from the final part of the Neolithic period beginning c. 6210 BC to the end of the Naqada III period c. 3000 BC. The dates of the Predynastic period were first defined before widespread archaeological excavation of Egypt took place, and recent finds indicating a very gradual Predynastic development have led to controversy over when exactly the Predynastic period ended. Thus, various terms such as "Protodynastic period", "Zero Dynasty" or "Dynasty 0"[1] are used to name the part of the period which might be characterized as Predynastic by some and Early Dynastic by others.

The Predynastic period is generally divided into cultural eras, each named after the place where a certain type of Egyptian settlement was first discovered. However, the same gradual development that characterizes the Protodynastic period is present throughout the entire Predynastic period, and individual "cultures" must not be interpreted as separate entities but as largely subjective divisions used to facilitate study of the entire period.

The vast majority of Predynastic archaeological finds have been in Upper Egypt, because the silt of the Nile River was more heavily deposited at the Delta region, completely burying most Delta sites long before modern times.[2]

Paleolithic

[edit]Egypt has been inhabited by humans (including archaic humans) for over a million (and probably over 2 million) years, though the evidence for early occupation of Egypt is sparse and fragmentary. The oldest archaeological finds in Egypt, stone tools belonging to the Oldowan industry, are poorly dated. These tools are succeeded by those belonging to the Acheulean industry.[3] The youngest Achulean sites in Egypt date to around 400-300,000 years ago.[4]

During the Late Pleistocene, when Egypt was occupied by modern humans, several archaeological industries are recognised including the Silsilian, Fakhurian, Afian, Kubbaniyan, Idfuan-Shuwikhatian, and the Isnan industries.[5]

Wadi Halfa

[edit]

Some of the oldest known structures were discovered in Egypt by archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski along the southern border near Wadi Halfa, Sudan, at the Arkin 8 site. Chmielewski dated the structures to 100,000 BC.[6] The remains of the structures are oval depressions about 30 cm deep and 2 × 1 meters across. Many are lined with flat sandstone slabs which served as tent rings supporting a dome-like shelter of skins or brush. This type of dwelling provided a place to live, but if necessary, could be taken down easily and transported. They were mobile structures—easily disassembled, moved, and reassembled—providing hunter-gatherers with semi-permanent habitation.[6]

Aterian industry

[edit]Aterian tool-making reached Egypt c. 40,000 BC.[6]

Khormusan industry

[edit]The Khormusan industry in Egypt began between 42,000 and 32,000 BP.[6] Khormusans developed tools not only from stone but also from animal bones and hematite.[6] They also developed small arrow heads resembling those of Native Americans,[6] but no bows have been found.[6] The end of the Khormusan industry came around 16,000 B.C. with the appearance of other cultures in the region, including the Gemaian.[7]

Late Paleolithic

[edit]The Late Paleolithic in Egypt started around 30,000 BC.[6] The Nazlet Khater skeleton was found in 1980 and given an age of 33,000 years in 1982, based on nine samples ranging between 35,100 and 30,360 years old.[8] This specimen is the only complete modern human skeleton so far found from the earliest Late Stone Age in Africa.[9]

The Fakhurian late Paleolithic industry in Upper Egypt, showed that a homogenous population existed in the Nile-Valley during the late Pleistocene. Studies of the skeletal material showed they were in the range of variation found in the Wadi Halfa, Jebel Sahaba and fragments from the Kom Ombo populations.[10]

Mesolithic

[edit]Halfan and Kubbaniyan culture

[edit]

The Halfan and Kubbaniyan, two closely related industries, flourished along the Upper Nile Valley. Halfan sites are found in the far north of Sudan, whereas Kubbaniyan sites are found in Upper Egypt. For the Halfan, only four radiocarbon dates have been produced. Schild and Wendorf (2014) discard the earliest and latest as erratic and conclude that the Halfan existed c. 22.5-22.0 ka cal BP.[11] People survived on a diet of large herd animals and the Khormusan tradition of fishing. Greater concentrations of artifacts indicate that they were not bound to seasonal wandering, but settled for longer periods.[citation needed] The Halfan culture was derived in turn from the Khormusan,[a][13][page needed] which depended on specialized hunting, fishing, and collecting techniques for survival. The primary material remains of this culture are stone tools, flakes, and a multitude of rock paintings.

Sebilian culture

[edit]The Sebilian culture began around 13,000 BC and vanished around 10,000 BC.[citation needed] In Egypt, analyses of pollen found at archaeological sites indicate that the people of the Sebilian culture (also known as the Esna culture) were gathering grains,[citation needed] though domesticated seeds were not found.[14] It has been hypothesized that the sedentary lifestyle practiced by these grain gatherers led to increased warfare, which was detrimental to sedentary life and brought this period to an end.[14]

Qadan culture

[edit]The Qadan culture (13,000–9,000 BC) was a Mesolithic industry that, archaeological evidence suggests, originated in Upper Egypt (present-day south Egypt) approximately 15,000 years ago.[15][16] The Qadan subsistence mode is estimated to have persisted for approximately 4,000 years. It was characterized by hunting, as well as a unique approach to food gathering that incorporated the preparation and consumption of wild grasses and grains.[15][16] Systematic efforts were made by the Qadan people to water, care for, and harvest local plant life, but grains were not planted in ordered rows.[17]

Around twenty archaeological sites in Upper Nubia give evidence for the existence of the Qadan culture's grain-grinding culture. Its makers also practiced wild grain harvesting along the Nile during the beginning of the Sahaba Daru Nile phase, when desiccation in the Sahara caused residents of the Libyan oases to retreat into the Nile valley.[14] Among the Qadan culture sites is the Jebel Sahaba cemetery, which has been dated to the Mesolithic.[18]

Qadan peoples were the first to develop sickles and they also developed grinding stones independently to aid in the collecting and processing of these plant foods prior to consumption.[6] However, there are no indications of the use of these tools after 10,000 BC, when hunter-gatherers replaced them.[6]

Neolithic to Proto-Dynastic

[edit]Early evidence for Neolithic cultures in the Nile Valley are generally located in the north of Egypt, exhibiting well-developed stages of Neolithic subsistence, including the cultivation of crops and sedentism, as well as pottery production from the late 6th Millennium BC onwards.[19]

The natural scientist Frederick Falkenburger in 1947, based on a sample set of around 1,800 prehistoric Egyptian crania, noted great heterogeneity amongst his samples. Falkenburger categorized them based on the nasal index, overall head and face form, taking into account width, eye socket structure, amongst other given indicators. He divided and characterized the skulls into four types: Cro-Magnon type, "Negroid" type, Mediterranean type, and mixed types resulting from the mixture of the aforementioned groups.[20] Similarly, the craniometrics of early Egyptians were according to the physician and anthropologist Eugene Strouhal in 1971, designated as either Cro-Magnon of North Africa, Mediterranean, "Negroid" of East Africa, and intermediate/mixed.[21]

According to professor Fekhri A. Hassan, the peopling of the Egyptian Nile Valley from archaeological and biological data, was the result of a complex interaction between coastal northern Africans, “neolithic” Saharans, Nilotic hunters, and riverine proto-Nubians with some influence and migration from the Levant (Hassan, 1988).[22]

Lower Egypt

[edit]Faiyum cultures

[edit]Faiyum B, Qarunian culture

[edit]Faiyum B culture, also called Qarunian due to being of the Lake Qarun or Qaroun area is an Epipalaeolithic (also called Mesolithic) culture and predates Faiyum A culture. No pottery has been found, with blade types being both plain and microlithic blades. A set of gouges and arrow-heads suggests it may have had contact with the Sahara (c. 6500 to - 5190 BC).[23][24]

Maciej Henneberg (1989) documented a remote 8,000 year old female skull from the Qarunian. It showed closest affinity to Wadi Halfa, modern Negroes and Australian aborigines, being quite different from Epipalaeolithic materials of Northern Africa usually labelled as Mechta-Afalou (Paleo-Berber) or the later Proto-Mediterranean types (Capsian). The skull still had an intermediate position, being gracile, but possessing large teeth and a heavy set jaw.[25] Similar results would later be found by a short report from SOY Keita in 2021, showing affinities with the Qarunian skull and the Teita series.[26]

Faiyum A culture

[edit]

Dating to about 5600-4400 BC of the Faiyum Neolithic,[19][27] continued expansion of the desert forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently, adopting increasingly sedentary lifestyles. The Faiyum A industry is the earliest farming culture in the Nile Valley.[19] Archaeological deposits that have been found are characterized by concave base projectile points and pottery. Around 6210 BC, Neolithic settlements appear all over Egypt.[28] Some studies based on morphological,[29] genetic,[30][31][32][33][34] and archaeological data[35][36][37][38][39] have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent in the Near East returning during the Egyptian and North African Neolithic, bringing agriculture to the region.

Studies in anthropology and post-cranial data has linked the earliest farming populations at Faiyum, Merimde, and El-Badari, to Near Eastern populations.[40][41][42] The archaeological data also suggests that Near Eastern domesticates were incorporated into a pre-existing foraging strategy and only slowly developed into a full-blown lifestyle.[b][44][45] Finally, the names for the Near Eastern domesticates imported into Egypt were not Sumerian or Proto-Semitic loan words.[46][47]

However, some scholars have disputed this view and cited linguistic,[48] physical anthropological,[49] archaeological[50][51][52] and genetic data[53][54][55][56][57] which does not support the hypothesis of a mass migration from the Levant during the prehistoric period. According to historian William Stiebling and archaeologist Susan N. Helft, this view posits that the ancient Egyptians are the same original population group as Nubians and other Saharan populations, with some genetic input from Arabian, Levantine, North African, and Indo-European groups who have known to have settled in Egypt during its long history. On the other hand, Stiebling and Helft acknowledge that the genetic studies of North African populations generally suggest a big influx of Near Eastern populations during the Neolithic Period or earlier. They also added that there have only been a few studies on ancient Egyptian DNA to clarify these issues.[58]

Egyptologist Ian Shaw (2003) wrote that "anthropological studies suggest that the predynastic population included a mixture of racial types (Negroid, Mediterranean and European)", but it is the skeletal material at the beginning of the pharaonic period that has proven to be most controversial. He said according to some scholars there may have been a much slower period of demographic change, than previously hypothesized rapid conquests of people coming into Egypt from the East. It probably involved the gradual infiltration of a different physical type from Syria-Palestine, via the eastern Delta.[59]

Weaving is evidenced for the first time during the Faiyum A Period. People of this period, unlike later Egyptians, buried their dead very close to, and sometimes inside, their settlements.[60]

Although archaeological sites reveal very little about this time, an examination of the many Egyptian words for "city" provides a hypothetical list of causes of Egyptian sedentarism. In Upper Egypt, terminology indicates trade, protection of livestock, high ground for flood refuge, and sacred sites for deities.[62]

Merimde culture

[edit]From about 5000 to 4200 BC the Merimde culture, so far only known from Merimde Beni Salama, a large settlement site at the edge of the Western Delta, flourished in Lower Egypt. The culture has strong connections to the Faiyum A culture as well as the Levant. People lived in small huts, produced a simple undecorated pottery and had stone tools. Cattle, sheep, goats and pigs were held. Wheat, sorghum and barley were planted. The Merimde people buried their dead within the settlement and produced clay figurines. The first life-sized Egyptian head made of clay comes from Merimde.[63]

El Omari culture

[edit]The El Omari culture is known from a small settlement near modern Cairo. People seem to have lived in huts, but only postholes and pits survive. The pottery is undecorated. Stone tools include small flakes, axes and sickles. Metal was not yet known.[64] Their sites were occupied from 4000 BC to the Archaic Period (3,100 BC).[65]

Maadi culture

[edit]

The Maadi culture (also called Buto Maadi culture) is the most important Lower Egyptian prehistoric culture dated about 4000–3500 BC,[67] and contemporary with Naqada I and II phases in Upper Egypt. The culture is best known from the site Maadi near Cairo, as well as the site of Buto,[68] but is also attested in many other places in the Delta to the Faiyum region. This culture was marked by development in architecture and technology. It also followed its predecessor cultures when it comes to undecorated ceramics.[69]

Copper was known, and some copper adzes have been found. The pottery is hand-made; it is simple and undecorated. Presence of black-topped red pots indicate contact with the Naqada sites in the south. Many imported vessels from Palestine have also been found. Black basalt stone vessels were also used.[67]

People lived in small huts, partly dug into the ground. The dead were buried in cemeteries, but with few burial goods. The Maadi culture was replaced by the Naqada III culture; whether this happened by conquest or infiltration is still an open question.[70]

The developments in Lower Egypt in the times previous to the unification of the country have been the subject of considerable disputes over the years. The recent excavations at Tell el-Farkha, Sais, and Tell el-Iswid have clarified this picture to some extent. As a result, the Chalcolithic Lower Egyptian culture is now emerging as an important subject of study.[71]

Gallery

[edit]-

Clapper discovered in Maadi, Louvre Museum

-

Carved catfish bones, and jar discovered in Maadi

-

Possible prisoners and wounded men of the Buto-Maadi culture devoured by animals, while one is led by a man in long dress, probably an Egyptian official (fragment, top right corner). Battlefield Palette.[66][72]

Upper Egypt

[edit]Tasian culture

[edit]

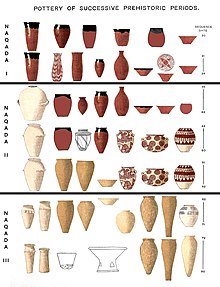

The Tasian culture appeared around 4500 BC in Upper Egypt. This culture group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery that is colored black on the top portion and interior.[60] This pottery is vital to the dating of Predynastic Egypt. Because all dates for the Predynastic period are tenuous at best, WMF Petrie developed a system called sequence dating by which the relative date, if not the absolute date, of any given Predynastic site can be ascertained by examining its pottery.

As the Predynastic period progressed, the handles on pottery evolved from functional to ornamental. The degree to which any given archaeological site has functional or ornamental pottery can also be used to determine the relative date of the site. Since there is little difference between Tasian ceramics and Badarian pottery, the Tasian Culture overlaps the Badarian range significantly.[73] From the Tasian period onward, it appears that Upper Egypt was influenced strongly by the culture of Lower Egypt.[74] Archaeological evidence has suggested that "the Tasian and Badarian Nile Valley sites were a peripheral network of earlier African cultures of around which Badarian, Saharan, Nubian, and Nilotic peoples regularly circulated."[75] Bruce Williams, Egyptologist, has argued that the Tasian culture was significantly related to the Sudanese-Saharan traditions from the Neolithic era which extended from regions north of Khartoum to locations near Dongola in Sudan.[76]

Badarian culture

[edit]

The Badarian culture, from about 4400 to 4000 BC,[77] is named for the Badari site near Der Tasa. It followed the Tasian culture, but was so similar that many consider them one continuous period. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called blacktop-ware (albeit much improved in quality) and was assigned Sequence Dating numbers 21–29.[73] The primary difference that prevents scholars from merging the two periods is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone and are thus Chalcolithic settlements, while the Neolithic Tasian sites are still considered Stone Age.[73]

Badarian flint tools continued to develop into sharper and more shapely blades, and the first faience was developed.[78] Distinctly Badarian sites have been located from Nekhen to a little north of Abydos.[79] It appears that the Faiyum A culture and the Badarian and Tasian Periods overlapped significantly; however, the Faiyum A culture was considerably less agricultural and was still Neolithic in nature.[78][80] Many biological anthropological studies have shown strong biological affinities between the Badarians and other Northeast African populations.[81][82][83][84][85][86] However, according to Eugene Strouhal and other anthropologists, Predynastic Egyptians like the Badarians were similar to the Capsian culture of North Africa and to Berbers.[87]

In 2005, Keita examined Badarian crania from predynastic upper Egypt in comparison to various European and tropical African crania. He found that the predynastic Badarian series clustered much closer with the tropical African series. Although, no Asian or other North African samples were included in the study as the comparative series were selected based on "Brace et al.'s (1993) comments on the affinities of an upper Egyptian/Nubian epipaleolithic series". Keita further noted that additional analysis and material from Sudan, late dynastic northern Egypt (Gizeh), Somalia, Asia and the Pacific Islands "show the Badarian series to be most similar to a series from the northeast quadrant of Africa and then to other Africans".[88]

Dental trait analysis of Badarian fossils conducted in a thesis study found that they were closely related to both Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting Northeast Africa, as well as the Maghreb. Among the ancient populations, the Badarians were nearest to other ancient Egyptians (Naqada, Hierakonpolis, Abydos and Kharga in Upper Egypt; Hawara in Lower Egypt), and C-Group and Pharaonic era skeletons excavated in Lower Nubia, followed by the A-Group culture bearers of Lower Nubia, the Kerma and Kush populations in Upper Nubia, the Meroitic, X-Group and Christian period inhabitants of Lower Nubia, and the Kellis population in the Dakhla Oasis.[89]: 219–20 Among the recent groups, the Badari markers were morphologically closest to the Shawia and Kabyle Berber populations of Algeria as well as Bedouin groups in Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, followed by other Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa.[89]: 222–224 The Late Roman era Badarian skeletons from Kellis were also phenotypically distinct from those belonging to other populations in Sub-Saharan Africa.[89]: 231–32

Naqada culture

[edit]

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (c. 4000–3000 BC), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. It is divided in three sub-periods: Naqada I, II and III.

Similar to the preceding Badarian culture, studies have found Naqada skeletal remains to have Northeast African affinities.[90][91][92][93][94][95] A study by Dr. Shormaka Keita found that Naqada remains were conforming almost equally to two local types, a southern Egyptian pattern (which shares closest resemblance with Kerma), and a northern Egyptian pattern (most similar to Coastal Maghreb).[96]

In 1996, Lovell and Prowse also reported the presence of individuals buried at Naqada in what they interpreted to be elite, high status tombs, showing them to be an endogamous ruling or elite segment of the local population at Naqada, which is more closely related to populations in northern Nubia (A-Group) than to neighbouring populations in southern Egypt. Specifically, they stated the Naqda samples were "more similar to the Lower Nubian protodynastic sample than they are to the geographically more proximate southern Egyptian samples" in Qena and Badari. However, they found the skeletal samples from the Naqada cemeteries to be significantly different to protodynastic populations in northern Nubia and predynastic Egyptian samples from Badari and Qena, which were also significantly different to northern Nubian populations.[97] Overall, both the elite and nonelite individuals in the Naqada cemeteries were more similar to each other than they were to the samples in northern Nubia or to samples from Badari and Qena in southern Egypt.[98]

In 2023, Christopher Ehret reported that the physical anthropological findings from the "major burial sites of those founding locales of ancient Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE, notably El-Badari as well as Naqada, show no demographic indebtedness to the Levant". Ehret specified that these studies revealed cranial and dental affinities with "closest parallels" to other longtime populations in the surrounding areas of northeastern Africa "such as Nubia and the northern Horn of Africa". He further commented that "members of this population did not come from somewhere else but were descendants of the long-term inhabitants of these portions of Africa going back many millennia". Ehret also cited existing, archaeological, linguistic and genetic data which he argued supported the demographic history.[99]

Amratian culture (Naqada I)

[edit]

The Amratian culture lasted from about 4000 to 3500 BC.[77] It is named after the site of El-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra is the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group, but this period is better attested at the Naqada site, so it also is referred to as the Naqada I culture.[78] Black-topped ware continues to appear, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which has been decorated with close parallel white lines being crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, is also found at this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system.[100]

Newly excavated objects attest to increased trade between Upper and Lower Egypt at this time. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not mined in Egypt, was imported from the Sinai, or possibly Nubia. Obsidian[101] and a small amount of gold[100] were both definitely imported from Nubia. Trade with the oases also was likely.[101]

New innovations appeared in Amratian settlements as precursors to later cultural periods. For example, the mud-brick buildings for which the Gerzean period is known were first seen in Amratian times, but only in small numbers.[102] Additionally, oval and theriomorphic cosmetic palettes appear in this period, but the workmanship is very rudimentary and the relief artwork for which they were later known is not yet present.[103][104][full citation needed]

Gerzean culture (Naqada II)

[edit]

The Gerzean culture, from about 3500 to 3200 BC,[77] is named after the site of Gerzeh. It was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation of Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture is largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt, but failing to dislodge Amratian culture in Nubia.[105] Gerzean pottery is assigned values from S.D. 40 through 62, and is distinctly different from Amratian white cross-lined wares or black-topped ware.[100] Gerzean pottery was painted mostly in dark red with pictures of animals, people, and ships, as well as geometric symbols that appear derived from animals.[105] Also, "wavy" handles, rare before this period (though occasionally found as early as S.D. 35) became more common and more elaborate until they were almost completely ornamental.[100]

Gerzean culture coincided with a significant decline in rainfall,[106] and farming along the Nile now produced the vast majority of food,[105] though contemporary paintings indicate that hunting was not entirely forgone. With increased food supplies, Egyptians adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle and cities grew as large as 5,000.[105]

It was in this time that Egyptian city dwellers stopped building with reeds and began mass-producing mud bricks, first found in the Amratian Period, to build their cities.[105]

Egyptian stone tools, while still in use, moved from bifacial construction to ripple-flaked construction. Copper was used for all kinds of tools,[105] and the first copper weaponry appears here.[79] Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally,[105] and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.[79]

The first tombs in classic Egyptian style were also built, modeled after ordinary houses and sometimes composed of multiple rooms.[101] Although further excavations in the Delta are needed, this style is generally believed to originate there and not in Upper Egypt.[101]

Although the Gerzean Culture is now clearly identified as being the continuation of the Amratian period, significant Mesopotamian influence worked its way into Egypt during the Gerzean, interpreted in previous years as evidence of a Mesopotamian ruling class, the so-called dynastic race, coming to power over Upper Egypt. This idea no longer attracts academic support.

Distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt during this period, indicating contacts with several parts of Asia. Objects such as the Gebel el-Arak knife handle, which has patently Mesopotamian relief carvings on it, have been found in Egypt,[109] and the silver which appears in this period can only have been obtained from Asia Minor.[105]

In addition, Egyptian objects are created which clearly mimic Mesopotamian forms, although not slavishly.[111] Cylinder seals appear in Egypt, as well as recessed paneling architecture, the Egyptian reliefs on cosmetic palettes are clearly made in the same style as the contemporary Mesopotamian Uruk culture, and the ceremonial mace heads which turn up from the late Gerzean and early Semainean are crafted in the Mesopotamian "pear-shaped" style, instead of the Egyptian native style.[106]

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but contact with Canaan does not predate the early dynastic, so it is usually assumed to have been conducted over water.[112] During the time when the Dynastic Race Theory was still popular, it was theorized that Uruk sailors circumnavigated Arabia, but a Mediterranean route, probably by middlemen through Byblos, is more likely, as evidenced by the presence of Byblian objects in Egypt.[112]

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis that lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then taken the Red Sea).[113] Also, it is considered unlikely that something so complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and at least a small contingent of migrants is often suspected.[112]

Despite this evidence of foreign influence, Egyptologists generally agree that the Gerzean Culture is still predominantly indigenous to Egypt.

Protodynastic Period (Naqada III)

[edit]

The Naqada III period, from about 3200 to 3000 BC,[77] is generally taken to be identical with the Protodynastic period, during which Egypt was unified.

Naqada III is notable for being the first era with hieroglyphs (though this is disputed by some), the first regular use of serekhs, the first irrigation, and the first appearance of royal cemeteries.[114]

The relatively affluent Maadi suburb of Cairo is built over the original Naqada stronghold.[115]

Bioarchaeologist Nancy Lovell had stated that there is a sufficient body of morphological evidence to indicate that ancient southern Egyptians had physical characteristics "within the range of variation" of both ancient and modern indigenous peoples in the Sahara and tropical Africa. She summarised that "In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas",[116] but exhibited local variation in an African context.[117]

-

Protodynastic sceptre fragment with royal couple. Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst, Munich

-

Fragment of a ceremonial palette illustrating a man and a type of staff. Circa 3200–3100 BC, Predynastic, Late Naqada III.

Lower Nubia

[edit]Lower Nubia is located within the borders of modern-day Egypt but is south of the border of Ancient Egypt, which was located at the first cataract of the Nile.

Nabta Playa

[edit]

Nabta Playa was once a large internally drained basin in the Nubian Desert, located approximately 800 kilometers south of modern-day Cairo[118] or about 100 kilometers west of Abu Simbel in southern Egypt,[119] 22.51° north, 30.73° east.[120] Today the region is characterized by numerous archaeological sites.[119] The Nabta Playa archaeological site, one of the earliest of the Egyptian Neolithic Period, is dated to circa 7500 BC.[121][122] Also, excavations from Nabta Playa, located about 100 km west of Abu Simbel for example, suggest that the Neolithic inhabitants of the region included migrants from both Sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean area.[123][124] According to Christopher Ehret, the material cultural indicators correspond with the conclusion that the inhabitants of the wider Nabta Playa region were a Nilo-Saharan-speaking population.[125]

Timeline

[edit]- Late Paleolithic, from 40th millennium BC

- Neolithic, from 11th millennium BC

- c. 10,500 BC: Wild grain harvesting along the Nile, grain-grinding culture creates world's earliest stone sickle blades[6] roughly at end of Pleistocene

- c. 8000 BC: Migration of peoples to the Nile, developing a more centralized society and settled agricultural economy

- c. 7500 BC: Importing animals from Asia to Sahara

- c. 7000 BC: Agriculture—animal and cereal—in East Sahara

- c. 7000 BC: in Nabta Playa deep year-round water wells dug, and large organized settlements designed in planned arrangements

- c. 6000 BC: Rudimentary ships (rowed, single-sailed) depicted in Egyptian rock art

- c. 5500 BC: Stone-roofed subterranean chambers and other subterranean complexes in Nabta Playa containing buried sacrificed cattle

- c. 5000 BC: Alleged archaeoastronomical stone megalith in Nabta Playa.[126][127]

- c. 5000 BC: Badarian: furniture, tableware, models of rectangular houses, pots, dishes, cups, bowls, vases, figurines, combs

- c. 4400 BC: finely-woven linen fragment[128]

- From 4th millennium BC, inventing has become prevalent

- c. 4000 BC: early Naqadan trade[129]

- 4th millennium BC: Gerzean tomb-building, including underground rooms and burial of furniture and amulets

- 4th millennium BC: Cedar imported from Lebanon[citation needed]

- c. 3900 BC: An aridification event in the Sahara leads to human migration to the Nile Valley[130]

- c. 3500 BC: Lapis lazuli imported from Badakshan and / or Mesopotamia

- c. 3500 BC: Senet, world's oldest (confirmed) board game

- c. 3500 BC: Faience, world's earliest-known glazed ceramic beads[citation needed]

- c. 3400 BC: Cosmetics,[citation needed] donkey domestication,[citation needed] (meteoric) iron works,[131] mortar (masonry)

- c. 3300 BC: Double reed instruments and lyres (see Music of Egypt)

- c. 3100 BC: Pharaoh Narmer, or Menes, or possibly Hor-Aha unified Upper and Lower Egypt

Relative chronology

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Khormusan is defined as a Middle Palaeolithic industry while the Halfan is defined as an Epipalaeolithic industry. According to scholarly opinion, the Khormusan and the Halfan are viewed as separate and distinct cultures.[12]

- ^ Settler colonists from the Near East would most likely have merged with the indigenous cultures resulting in a mixed economy with the agricultural aspect of the economy increasing in frequency through time, which is what the archaeological record more precisely indicates. Both pottery, lithics, and economy with Near Eastern characteristics, and lithics with North African characteristics are present in the Fayum A culture.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name : ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-735-5.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ Bakry, Aboualhassan; Saied, Ahmed; Ibrahim, Doaa (21 July 2020). "The Oldowan in the Egyptian Nile Valley". Journal of African Archaeology. 18 (2): 229–241. doi:10.1163/21915784-20200010. ISSN 1612-1651.

- ^ Michalec, Grzegorz; Cendrowska, Marzena; Andrieux, Eric; Armitage, Simon J.; Ehlert, Maciej; Kim, Ju Yong; Sohn, Young Kwan; Krupa-Kurzynowska, Joanna; Moska, Piotr; Szmit, Marcin; Masojć, Mirosław (17 November 2021). "A Window into the Early–Middle Stone Age Transition in Northeastern Africa—A Marine Isotope Stage 7a/6 Late Acheulean Horizon from the EDAR 135 Site, Eastern Sahara (Sudan)". Journal of Field Archaeology. 46 (8): 513–533. doi:10.1080/00934690.2021.1993618. ISSN 0093-4690.

- ^ Leplongeon, Alice (27 December 2017). Pinhasi, Ron (ed.). "Technological variability in the Late Palaeolithic lithic industries of the Egyptian Nile Valley: The case of the Silsilian and Afian industries". PLOS ONE. 12 (12): e0188824. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1288824L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188824. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5744920. PMID 29281660.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Ancient Egyptian Culture: Paleolithic Egypt". Emuseum. Minnesota: Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ Nicolas-Christophe Grimal. A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 20. Blackwell (1994). ISBN 0-631-19396-0

- ^ "Dental Anthropology" (PDF). Anthropology.osu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Bouchneba, L.; Crevecoeur, I. (2009). "The inner ear of Nazlet Khater 2 (Upper Paleolithic, Egypt)". Journal of Human Evolution. 56 (3): 257–262. Bibcode:2009JHumE..56..257B. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.003. PMID 19144388.

- ^ Lubell, David (1974). The Fakhurian: A Late Paleolithic Industry from Upper Egypt. Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Wealth, Geological Survey of Egypt and Mining Authority.

- ^ R. Schild; F. Wendorf (2014). "Late Palaeolithic Hunter-Gatherers in the Nile Valley of Nubia and Upper Egypt". In E A. A. Garcea (ed.). South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 years ago. Oxbow Books. pp. 89–125.

- ^ "Prehistory of Nubia". Numibia.net. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Reynes, Midant-Beatrix (2000). The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Pharohs. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21787-8.

- ^ a b c Grimal, Nicolas (1988). A History of Ancient Egypt. Librairie Arthéme Fayard. p. 21.

- ^ a b Phillipson, DW: African Archaeology p. 149. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- ^ a b Shaw, I & Jameson, R: A Dictionary of Archaeology, p. 136. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2002.

- ^ Darvill, T: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Copyright © 2002, 2003 by Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kelly, Raymond (October 2005). "The evolution of lethal intergroup violence". PNAS. 102 (43): 24–29. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10215294K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102. PMC 1266108. PMID 16129826.

- ^ a b c Köhler, E. Christiana (2011). "Neolithic in the Nile Valley (Fayum A, Merimde, el-Omari, Badarian)". Archéo-Nil. 21 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3406/arnil.2011.1023.

- ^ Boëtsch, Gilles (31 December 1995). "Noirs ou blancs : une histoire de l'anthropologie biologique de l'Égypte". Égypte/Monde arabe (in French) (24): 113–138. doi:10.4000/ema.643. ISSN 1110-5097.

Falkenburger also notes a great heterogeneity in the measurements taken on 1,800 Egyptian skulls. From indices expressing the shape of the face, nose and orbits, Falkenburger divides the ancient Egyptians into four types - Cro-Magnon type, Negroid type, Mediterranean type and mixed type, resulting from the mixture of the first three.

- ^ Strouhal, Eugen (1 January 1971). "Evidence of the early penetration of Negroes into prehistoric Egypt". The Journal of African History. 12 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000037. ISSN 1469-5138.

- ^ Hassan, Fekri A. (1 June 1988). "The Predynastic of Egypt". Journal of World Prehistory. 2 (2): 135–185. doi:10.1007/BF00975416. ISSN 1573-7802.

- ^ "Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B) (about 6700-5300 BC?)". Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Ki-Zerbo[editor], Joseph (1989). "General history of Africa, abridged edition, v. 1: Methodology and African prehistory". UNESCO Digital Library. The University of California Press. p. 281. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Hendrickx, Stan; Claes, Wouter; Tristant, Yann. "IFAO - Bibliographie de l'Égypte des Origines : #2998 = The Early Neolithic, Qarunian burial from the Northern Fayum Desert (Egypt)". www.ifao.egnet.net (in French). Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y (1 August 2020). "Title: Short Report: Morphometric Affinity of the Qarunian Early Egyptian Skull Explored With Fordisc 3.0". Academia.edu.

- ^ "Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B) (about 6000-5000 BC?)". Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Redford, Donald B (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; Seguchi, Noriko; Quintyn, Conrad B.; Fox, Sherry C.; Nelson, A. Russell; Manolis, Sotiris K.; Qifeng, Pan (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

- ^ Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA (2002). "Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99 (17): 11008–11013. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9911008C. doi:10.1073/pnas.162158799. PMC 123201. PMID 12167671.

- ^ "Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans, Dupanloup et al., 2004". Mbe.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Semino, O; Magri, C; Benuzzi, G; et al. (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area, 2004". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza (1997). "Paleolithic and Neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool". Am J Hum Genet. 61 (1): 247–54. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64303-1. PMC 1715849. PMID 9246011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Chikhi (21 July 1998). "Clines of nuclear DNA markers suggest a largely Neolithic ancestry of the European gene". PNAS. 95 (15): 9053–9058. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9053C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9053. PMC 21201. PMID 9671803.

- ^ Bar Yosef, Ofer (1998). "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture". Evolutionary Anthropology. 6 (5): 159–177. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-7. S2CID 35814375.

- ^ Zvelebil, M. (1986). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies and the Transition to Farming. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–15, 167–188.

- ^ Bellwood, P. (2005). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- ^ Dokládal, M.; Brožek, J. (1961). "Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments". Current Anthropology. 2 (5): 455–477. doi:10.1086/200228. S2CID 161324951.

- ^ Zvelebil, M. (1989). "On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a reply to Ammerman (1989)". Antiquity. 63 (239): 379–383. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00076110. S2CID 162882505.

- ^ Smith, P. (2002) The palaeo-biological evidence for admixture between populations in the southern Levant and Egypt in the fourth to third millennia BC. In: Egypt and the Levant: Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium BC, London–New York: Leicester University Press, 118–128

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. (2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers from El-Badari: Aboriginals or "European" Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ Kemp, B. 2005 "Ancient Egypt Anatomy of a Civilisation". Routledge. p. 52–60

- ^ Shirai, Noriyuki (2010). The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New Insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic. Archaeological Studies Leiden University. Leiden University Press.

- ^ Wetterstrom, W. (1993). Shaw, T.; et al. (eds.). Archaeology of Africa. London: Routledge. pp. 165–226.

- ^ Rahmani, N. (2003). "Le Capsien typique et le Capsien supérieur". Cambridge Monographs in Archaeology (57). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y.; Boyce, A. J. (2005). "Genetics, Egypt and History: Interpreting Geographical Patterns of a Y-Chromosome Variation". History in Africa. 32: 221–46. doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0013. S2CID 163020672.

- ^ Ehret, C; Keita, SOY; Newman, P (2004). "The Origins of Afroasiatic a response to Diamond and Bellwood (2003)". Science. 306 (5702): 1680. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c. PMID 15576591. S2CID 8057990.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300.

- ^ "There is no evidence, no archaeological signal, for a mass migration (settler colonization)" into Egypt from southwest Asia at the time of the writing. Core Egyptian culture was well established. A total peopling of Egypt at this time from the Near East would have meant the mass migration of Semitic speakers. The ancient Egyptian language – using the usual academic language taxonomy – is a branch within Afroasiatic with one member (not counting place of origin/urheimat is within Africa, using standard linguistic criteria based on the locale of greatest diversity, deepest branches, and least moves accounting for its five or six branches or sevem, if Ongota is counted".[verification needed] Keita, S. O. Y. (September 2022). "Ideas about 'Race' in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of 'Racial' Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from 'Black Pharaohs' to Mummy Genomest". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

- ^ Wengrow, David; Dee, Michael; Foster, Sarah; Stevenson, Alice; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk (March 2014). "Cultural convergence in the Neolithic of the Nile Valley: a prehistoric perspective on Egypt's place in Africa". Antiquity. 88 (339): 95–111. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00050249. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 49229774.

- ^ Redford, Donald (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- ^ "P2 (PN2) marker, within the E haplogroup, connects the predominant Y chromosome lineage found in Africa overall after the modern human left Africa. P2/M215-55 is found from the Horn of Africa up through the Nile Valley and west to the Maghreb, and P2/V38/M2 is predominant in most of infra-Saharan tropical Africa". Shomarka, Keita (2022). "Ancient Egyptian 'Origins' and 'Identity'". Ancient Egyptian society: challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 111–122. ISBN 978-0367434632.

- ^ "Moreover, the available genetic evidence – relating in particular to the M35/215 Y-chromosome lineage – also accords with just this kind of demographic history. This lineage had its origins broadly in the Horn of Africa and East Africa." Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.

- ^ Trombetta, B.; Cruciani, F.; Sellitto, D.; Scozzari, R. (2011). "A new topology of the human Y chromosome haplogroup E1b1 (E-P2) revealed through the use of newly characterized binary polymorphisms". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e16073. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616073T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016073. PMC 3017091. PMID 21253605.

- ^ Cruciani, Fulvio; et al. (June 2007). "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. PMID 17351267.

- ^ Anselin, Alain H. (2011). Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1407307602.

- ^ Stiebing, William H. Jr.; Helft, Susan N. (3 July 2023). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-1-000-88066-3.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (23 October 2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. OUP Oxford. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-19-160462-1.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Alan (1964). Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press. p. 388.

- ^ Josephson, Jack. "Naqada IId, Birth of an Empire". p. 173.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ Eiwanger, Josef (1999). "Merimde Beni-salame". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 501–505. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ Mortensen, Bodil (1999). "el-Omari". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 592–594. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ "El-Omari". EMuseum. Mankato: Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010.

- ^ a b Brovarski, Edward (2016). "Reflections on the Battlefield and Libyan Booty Palettes". In Vandijk, J. (ed.). Another Mouthful of Dust: Egyptological Studies in Honour of Geoffrey Thorndike Martin. Leiden: Peeters. pp. 81–89.

- ^ a b "Maadi", University College London.

- ^ "Buto – Maadi Culture", Ancient Egypt Online.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (18 January 2016). "Predynastic Period in Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (1999). "Ma'adi and Wadi Digla". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 455–458. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ Mączyńska, Agnieszka (2018). "On the Transition Between the Neolithic and Chalcolithic in Lower Egypt and the Origins of the Lower Egyptian Culture: a Pottery Study" (PDF). Desert and the Nile. Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2023.

- ^ Davis, Whitney; Davis, George C.; Pardee, Helen N. (1992). Masking the Blow: The Scene of Representation in Late Prehistoric Egyptian Art. University of California Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-520-07488-0.

- ^ a b c Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 389.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.35. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988.

- ^ Excell, Karen (2011). Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2–4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1407307602.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1996). "The Qustul Incense Burner and the Case for a Nubian Origin of Ancient Egyptian Kingship". In Celenko, Theodore (ed.). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0936260648.

- ^ a b c d Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ a b c Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.24. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ a b c Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 391.

- ^ Newell, G. D. (2012). "A re-examination of the Badarian Culture". MA thesis.

- ^ "When Mahalanobis D2 was used,the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita, 1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or 'European' Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 40034328. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ Godde, Kanya. "A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period". Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ S. O. Y., Keita; A. J., Boyce (2008). "Temporal variation in phenetic affinity of early Upper Egyptian male cranial series". Human Biology. 80 (2): 141–159. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[141:TVIPAO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 18720900. S2CID 25207756.

- ^ "Keita (1992), using craniometrics, discovered that the Badarian series is distinctly different from the later Egyptian series, a conclusion that is mostly confirmed here. In the current analysis, the Badari sample more closely clusters with the Naqada sample and the Kerma sample". Godde, K. (2009). "An examination of Nubian and Egyptian biological distances: support for biological diffusion or in situ development?". Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 60 (5): 389–404. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2009.08.003. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 19766993.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Strohaul, Eugene. "Anthropology of the Egyptian Nubian Men - Strouhal - 2007 - ANTHROPOLOGIE" (PDF). Puvodni.MZM.cz: 115.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (November 2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or 'European' Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ a b c Haddow, Scott Donald (January 2012). "Dental Morphological Analysis of Roman Era Burials from the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt". Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "When Mahalanobis D2 was used, the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita, 1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20: 129–154. doi:10.2307/3171969. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171969. S2CID 162330365.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka (1996). "Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Godde, K. (2009). "An examination of Nubian and Egyptian biological distances: support for biological diffusion or in situ development?". Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 60 (5): 389–404. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2009.08.003. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 19766993.

- ^ Godde, Kanya (2020) [10–15 September 2017]. A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period. Egypt at its Origins 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference "Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt". Vienna: Peeters.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka. "Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report (1996)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy; Prowse, Tracy (October 1996). "Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 101 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<237::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 8893087.

Table 3 presents the MMD data for Badari, Qena, and Nubia in addition to Naqada and shows that these samples are all significantly different from each other. ... 1) the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites and 2) the Naqada samples are more similar to the Lower Nubian protodynastic sample than they are to the geographically more proximate Egyptian samples.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy; Prowse, Tracy (October 1996). "Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 101 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<237::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 8893087.

... the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites ...

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 82–85, 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 390.

- ^ a b c d Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 28. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press, p. 7.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1964), Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press, p. 393.

- ^ Newell, G. D., "The Relative chronology of PNC I" (Academia.Edu: 2012)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- ^ a b Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17.

- ^ a b "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Cooper, Jerrol S. (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9780931464966.

- ^ Shaw, Ian & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- ^ Christiansen, S. U.2023 What do the Figurines of "Bird Ladies" in Predynastic Egypt represent? (OAJAA)

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 18.

- ^ a b c Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 22.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 20.

- ^ "Naqada III". Faiyum.com. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "Maadi Culture". University College London. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sahara and tropical Africa. The distribution of population characteristics seems to follow a clinal pattern from south to north, which may be explained by natural selection as well as gene flow between neighboring populations. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas". Lovell, Nancy C. (1999). "Egyptians, physical anthropology of". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. pp. 328–331. ISBN 0415185890.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy C. (1999). "Egyptians, physical anthropology of" (PDF). In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. pp. 328–331. ISBN 0415185890.

- ^ Slayman, Andrew L. (27 May 1998), Neolithic Skywatchers, Archaeological Institute of America

- ^ a b Wendorf, Fred; Schild, Romuald (26 November 2000), Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa (Sahara), southwestern Egypt, Comparative Archaeology Web, archived from the original on 6 August 2011

- ^ Brophy, T. G.; Rosen, P. A. (2005). "Satellite Imagery Measures of the Astronomically Aligned Megaliths at Nabta Playa" (PDF). Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 5 (1): 15–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2008.

- ^ Margueron, Jean-Claude (2012). Le Proche-Orient et l'Égypte antiques (in French). Hachette Éducation. p. 380. ISBN 9782011400963.

- ^ Wendorf, Fred; Schild, Romuald (2013). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9781461506539.

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 489–502. ISBN 978-0-306-46612-0.

- ^ McKim Malville, J. (2015). "Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Southern Egypt". Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer. pp. 1080–1090. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_101. ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Malville, J. McKim (2015), "Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Egypt", in Ruggles, C.L.N. (ed.), Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, vol. 2, New York: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 1079–1091, ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1

- ^ Belmonte, Juan Antonio (2010), "Ancient Egypt", in Ruggles, Clive; Cotte, Michel (eds.), Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention: A Thematic Study, Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites/International Astronomical Union, pp. 119–129, ISBN 978-2-918086-07-9

- ^ "linen fragment". Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Shaw (2000), p. 61

- ^ Brooks, Nick (2006). "Cultural responses to aridity in the Middle Holocene and increased social complexity". Quaternary International. 151 (1): 29–49. Bibcode:2006QuInt.151...29B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2006.01.013.

- ^ "Iron beads were worn in Egypt as early as 4000 B.C., but these were of meteoric iron, evidently shaped by the rubbing process used in shaping implements of stone", quoted under the heading "Columbia Encyclopedia: Iron Age" at Iron Age, Answers.com. Also, see History of ferrous metallurgy#Meteoric iron—"Around 4000 BC small items, such as the tips of spears and ornaments, were being fashioned from iron recovered from meteorites" – attributed to R. F. Tylecote, A History of Metallurgy (2nd edition, 1992), p. 3.

External links

[edit]- Information about Ancient Egyptian History Archived 14 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine: from This Is Egypt | Information about Ancient Egyptian History

- Ancient Egyptian History - A comprehensive and concise educational website focusing on the basic and the advanced in all aspects of Ancient Egypt

- Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization - Oriental Institute

![Possible prisoners and wounded men of the Buto-Maadi culture devoured by animals, while one is led by a man in long dress, probably an Egyptian official (fragment, top right corner). Battlefield Palette.[66][72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/04/Battlefield_palette.jpg/200px-Battlefield_palette.jpg)