United States involvement in regime change: Difference between revisions

m Spelling |

GPRamirez5 (talk | contribs) Venezuela |

||

| Line 362: | Line 362: | ||

Former UN rapporteur [[Alfred de Zayas]] stated that US sanctions on Venezuela were illegal as they constituted [[economic warfare]] and "could amount to 'crimes against humanity' under international law."<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/venezuela-us-sanctions-united-nations-oil-pdvsa-a8748201.html|title=Venezuela crisis: Former UN rapporteur says US sanctions are killing citizens|last=Selby-Green|first=Michael|date=January 27, 2019|work=[[The Independent]]|access-date=January 28, 2019|location=}}</ref> He also said the US was "violating international law by attempting a 'coup' against the Venezuelan government".<ref>{{cite news|author=|date=January 24, 2019 |title=Former U.N. Expert: The U.S. Is Violating International Law by Attempting a Coup in Venezuela|url=https://www.democracynow.org/2019/1/24/former_un_expert_the_us_is|work=[[Democracy Now!]] |location= |access-date= January 28, 2019}}</ref> His report (which he says was ignored by the UN) was criticized by the Latin America and Caribbean programme director for the [[International Crisis Group|Crisis Group]] for neglecting to mention the impact of a "difficult business environment on the country", which the director said "was a symptom of [[Chavismo]] and the socialist governments’ failures", and that "Venezuela could not recover under current government policies even if the sanctions were lifted."<ref name="indreport">{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/venezuela-us-sanctions-united-nations-oil-pdvsa-a8748201.html|title=Venezuela crisis: Former UN rapporteur says US sanctions are killing citizens|last=Selby-Green|first=Michael|date=January 27, 2019|work=[[The Independent]]|access-date=January 28, 2019}}</ref> |

Former UN rapporteur [[Alfred de Zayas]] stated that US sanctions on Venezuela were illegal as they constituted [[economic warfare]] and "could amount to 'crimes against humanity' under international law."<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/venezuela-us-sanctions-united-nations-oil-pdvsa-a8748201.html|title=Venezuela crisis: Former UN rapporteur says US sanctions are killing citizens|last=Selby-Green|first=Michael|date=January 27, 2019|work=[[The Independent]]|access-date=January 28, 2019|location=}}</ref> He also said the US was "violating international law by attempting a 'coup' against the Venezuelan government".<ref>{{cite news|author=|date=January 24, 2019 |title=Former U.N. Expert: The U.S. Is Violating International Law by Attempting a Coup in Venezuela|url=https://www.democracynow.org/2019/1/24/former_un_expert_the_us_is|work=[[Democracy Now!]] |location= |access-date= January 28, 2019}}</ref> His report (which he says was ignored by the UN) was criticized by the Latin America and Caribbean programme director for the [[International Crisis Group|Crisis Group]] for neglecting to mention the impact of a "difficult business environment on the country", which the director said "was a symptom of [[Chavismo]] and the socialist governments’ failures", and that "Venezuela could not recover under current government policies even if the sanctions were lifted."<ref name="indreport">{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/venezuela-us-sanctions-united-nations-oil-pdvsa-a8748201.html|title=Venezuela crisis: Former UN rapporteur says US sanctions are killing citizens|last=Selby-Green|first=Michael|date=January 27, 2019|work=[[The Independent]]|access-date=January 28, 2019}}</ref> |

||

--> |

--> |

||

Shortly after [[Hugo Chávez]]’s election to president in 1998, the U.S. government-funded [[National Endowment for Democracy]] (NED) initiated guidance of Venezuelan political parties towards his defeat. NED agents traveled to Venezuela and met individually with Venezuelan party leaders from the opposition, offering guidance on how to electorally defeat Chávez''',''' construct coalition political platforms and reach out to youth. U.S. diplomats also met with the opposition over the course of a decade to advise strategy against Chavez. |

|||

Agencies such as the [[United States Agency for International Development|U.S. Agency for International Development]] (USAID) and Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) initiated operations developing neutral-looking organizations in poor neighborhoods focused on community initiatives such as participatory democracy. U.S. ambassador [[William Brownfield]] described how USAID/OTI, “directly reached approximately 238,000 adults through over 3,000 forums…providing opportunities for opposition activists to interact with hardcore Chavistas, with the desired effect of pulling them slowly away from Chavismo.” |

|||

USAID/OTI also materially supported the recently developed anti-Chávez student movement, which produced the political career of [[Juan Guaidó]] and other young opposition leaders. OTI functionaries provided students with resources including paper and microphones, paid for travel expenses, and organized seminars to maximize resistance to the socialist government. According to a Washington Post analysis, “U.S. diplomats regularly met with opposition student leaders who primarily operated in Caracas, discussing plans of action against the Chávez government.” |

|||

The campaign against Venezuela’s left-leaning government continued under four US presidents. Most recently, the [[Presidency of Donald Trump|Trump administration]] has recognized the unelected opposition leader Juan Guaido as president and openly threatened to launch military action to overthrow the government of [[Nicolás Maduro|Nicolas Maduro]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2019/02/19/the-u-s-has-covertly-supposed-the-venezuelan-opposition-for-years/?utm_term=.c32b52fb10e8|title=The US has quietly supported the Venezuelan opposition for years|last=Gill|first=Timothy M.|date=|work=Washington Post|access-date=}}</ref> |

|||

== Covert involvements == |

== Covert involvements == |

||

Revision as of 03:13, 3 April 2019

| History of the United States expansion and influence |

|---|

| Colonialism |

|

|

| Militarism |

|

|

| Foreign policy |

|

| Concepts |

United States involvement in regime change has entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government initiated actions for regime change mainly in Latin America and the southwest Pacific, and included the Mexican–American, Spanish–American and Philippine–American wars. At the onset of the 20th century the United States shaped or installed friendly governments in many countries around the world, including neighbors Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

During World War II, the United States helped overthrow many Nazi or imperial Japanese puppet regimes. Examples include regimes in the Philippines, Korea, the Eastern portion of China, and much of Europe. United states forces were also instrumental in ending the rule of Adolf Hitler over Germany and of Benito Mussolini over Italy.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. government expanded the geographic scope of its actions to foster regime change, as the country struggled with the Soviet Union for global leadership and influence within the context of the Cold War. Significant operations included the U.S. and UK-orchestrated 1953 Iranian coup d'état, the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion targeting Cuba, the anti-communist purge in Indonesia, and support for the Argentinian Dirty War, in addition to the U.S.'s traditional area of operations, Central America and the Caribbean. In addition, the U.S. has interfered in the national elections of many countries, including in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s to keep its preferred center-right Liberal Democratic Party in power using secret funds, in the Philippines to orchestrate the campaign of Ramon Magsaysay for president in 1953, and in Lebanon to help Christian parties in the 1957 elections using secret cash infusions.[1] The U.S. has executed at least 81 overt and covert known interventions in foreign elections during the period 1946–2000.[2]

Also after World War II, the United States in 1945 ratified[3] the UN Charter, the preeminent international law document,[4] which legally bound the U.S. government to the Charter's provisions, including Article 2(4), which prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations, except in very limited circumstances.[5] Therefore, any legal claim advanced to justify regime change by a foreign power carries a particularly heavy burden.[6]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has led or supported wars to determine the governance of a number of countries. Stated U.S. aims in these conflicts have included fighting the War on Terror as in the 2001 Afghan war, or removing dictatorial and hostile regimes in the 2003 Iraq War and 2011 military intervention in Libya.

19th century interventions

1846: U.S.–Mexico War

The Mexican–American War was an armed conflict between the United States of America and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory despite the 1836 Texas Revolution. The war began when Mexican troops attacked and defeated American troops in an area disputed between the U.S. and Mexico.[7]

American forces occupied New Mexico and California, then invaded parts of Northeastern Mexico and Northwestern Mexico; Another American army captured Mexico City, and the war ended with a victory for the United States. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo specified the major consequence of the war: the forced Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the U.S. in exchange for $18 million. In addition, the United States forgave debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico accepted the loss of Texas and thereafter cited the Rio Grande as its national border. The war did not result in a regime change in Mexico.

1887–1889: Samoa

The Samoan crisis was a confrontation between the United States, Germany and Great Britain from 1887 to 1889, with the powers backing rival claimants to the throne of the Samoan Islands during the Samoan Civil War.[8] The Second Samoan Civil War followed in 1898, involving the US (who backed the incumbent king) and Germany, eventually resulting, via the Tripartite Convention of 1899, in the partition of the Samoan Islands into American Samoa and German Samoa.[9][10]

1893–1917: U.S. empire and expansionism

1890s

1893: Kingdom of Hawaii

Anti-monarchial elements, mostly Americans, in Hawaii, engineered the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. On January 17, 1893, the native monarch, Queen Lili'uokalani, was overthrown. Hawaii was initially reconstituted as an independent republic, but the ultimate goal of the action was the annexation of the islands to the United States, which was finally accomplished in 1898.

1898: Cuba and Puerto Rico

As part of the Spanish–American War, the United States invaded and occupied Spanish-ruled Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898. Cuba was occupied by the U.S. from 1898 to 1902 under military governor Leonard Wood, and again from 1906 to 1909, in 1912 and from 1917 to 1922; governed by the terms of the Platt Amendment through 1934.

The Puerto Rican Campaign was an American military sea and land operation on the island of Puerto Rico during the Spanish–American War. The United States Navy attacked the archipelago's colonial capital, San Juan. Though the damage inflicted on the city was minimal, the Americans were able to establish a blockade in the city's harbor, San Juan Bay. The land offensive began on July 25 with 1,300 infantry soldiers. All military actions in Puerto Rico were suspended on August 13, after U.S. President William McKinley and French Ambassador Jules Cambon, acting on behalf of the Spanish government, signed an armistice whereby Spain relinquished its sovereignty over the territories of Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines and Guam.

1899: Philippines

The Philippine–American War was part of a series of conflicts in the Philippine struggle for independence against United States occupation. Fighting erupted between US and Filipino revolutionary forces on February 4, 1899, and quickly escalated into the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States.[11] The war officially ended on July 4, 1902.[12] This US intervention was intended to prevent regime change, and retain US control over the Philippines.

1898–1901: China

The Boxer Rebellion was a proto-nationalist movement in China between 1898 and 1901, so called because it was led by fighters who called themselves the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists. The United States was part of an Eight-Nation Alliance that brought 20,000 armed troops to China, defeated the Imperial Chinese Army, and captured Beijing. The Eight-Nation Alliance was a military coalition formed to defeat the rebellion, and the eight nations, in addition to the US, were Japan, Russia, Britain, France, the Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary.[13] The Boxer Protocol of September 7, 1901 ended the uprising.[14] This intervention did not result in regime change in China.

1900s

1903: Panama

In 1903, the U.S. aided the secession of Panama from the Republic of Colombia. The secession was engineered by a Panamanian faction backed by the Panama Canal Company, a French–US corporation whose aim was the construction of a waterway across the Isthmus of Panama thus connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In 1903, the U.S. signed the Hay-Herrán Treaty with Colombia, granting the United States use of the Isthmus of Panama in exchange for financial compensation.[15][16] amidst the Thousand Days' War. The Panama Canal was already under construction, and the Panama Canal Zone was carved out and placed under United States sovereignty. The US did not transfer the zone back to Panama until 2000.

1900s–1920s: Honduras

In what became known as the "Banana Wars," between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934, the U.S. staged many military invasions and interventions in Central America and the Caribbean.[17] The United States Marine Corps, which most often fought these wars, developed a manual called The Strategy and Tactics of Small Wars in 1921 based on its experiences. On occasion, the Navy provided gunfire support and Army troops were also used. The United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated Honduras' key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways. The U.S. staged invasions and incursions of US troops in 1903 (supporting a coup by Manuel Bonilla), 1907 (supporting Bonilla against a Nicaraguan-backed coup), 1911 and 1912 (defending the regime of Miguel R. Davila from an uprising), 1919 (peacekeeping during a civil war, and installing the caretaker government of Francisco Bográn), 1920 (defending the Bográn regime from a general strike), 1924 (defending the regime of Rafael López Gutiérrez from an uprising) and 1925 (defending the elected government of Miguel Paz Barahona) to defend US interests.[18] Writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.

1910s

1912–1933: Nicaragua

The U.S. government invaded Nicaragua in 1912 after intermittent US military landings and naval bombardments in the previous decades. The U.S. was providing political support to conservative-led forces who were rebelling against President José Santos Zelaya, a liberal. U.S. motives included disagreement with the proposed Nicaragua Canal, since the U.S. controlled the Panama Canal Zone, which included the Panama Canal, and President Zelaya's attempts to regulate access by foreigners to Nicaraguan natural resources. On November 17, 1909, two Americans were executed by order of Zelaya after the two men confessed to having laid a mine in the San Juan River with the intention of blowing up the Diamante. The U.S. justified the intervention by claiming to protect American lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year. The U.S. occupied the country almost continuously from 1912 through 1933.

1914: Mexico

U.S. troops invaded Veracruz in Mexico in 1914 following the Tampico Affair. The US occupied the city for six months.

1915–1934: Haiti

The U.S. occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934. US banks had lent money to Haiti and requested U.S. government intervention. The U.S. installed a new government in 1917 and dictated the terms of a new Haitian constitution in 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. The Cacos (military group) were originally armed militias of formerly enslaved persons who rebelled and took control of mountainous areas following the Haitian Revolution in 1804. Such groups fought a guerilla war against the US occupation in what were known as the "Caco Wars."[19]

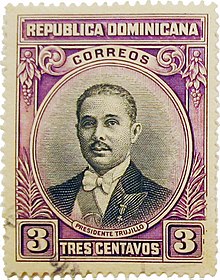

1916–1924: Dominican Republic

U.S. marines invaded the Dominican Republic and occupied it from 1916 to 1924, and this was preceded by US military interventions in 1903, 1904, and 1914. The US Navy installed its personnel in all key positions in government and controlled the Dominican army and police.[20] Within a couple of days, the constitutional president, Juan Isidro Jimenes, resigned.[21]

WWI and interwar period

1918: Russia

After the new Bolshevik government withdrew from World War I, the U.S. military together with forces of its Allies invaded Russia in 1918. Approximately 250,000 invading soldiers, including troops from Europe, the US and the Empire of Japan invaded Russia to aid the White Army against the Red Army of the new Soviet government in the Russian civil war. The invaders launched the North Russia invasion from Arkhangelsk and the Siberia invasion from Vladivostok. The invading forces included 13,000 U.S. troops whose mission after the end of World War I included the toppling of the new Soviet government and the restoration of the previous Tsarist regime. U.S. and other Western forces were unsuccessful in this aim and withdrew by 1920 but the Japanese military continued to occupy parts of Siberia until 1922 and the northern half of Sakhalin until 1925.[22]

1941: Panama

The United States government used its contacts in the Panama National Guard, which the U.S. had earlier trained, to orchestrate a coup against the government of Panama in October 1941. The U.S. had requested that the government of Panama allow it to build over 130 new military installations inside and outside of the Panama Canal Zone, and the government of Panama refused this request at the price suggested by the U.S.[23] President Arnulfo Arias fled the country and Ricardo Adolfo de la Guardia Arango, the leader of the coup and a friend of the US government, became president.[24]

World War 2 and aftermath

1944-6: France

British, Canadian and United States forces were the critical participants in Operation Goodwood and Operation Cobra, leading to a military breakout which ended the Nazi occupation of France. The actual Liberation of Paris was accomplished by French forces. The French formed the Provisional Government of the French Republic in 1944, leading to the formation of the French Fourth Republic in 1946.

The liberation of France is celebrated regularly up to the present day.[25][26]

1944-5: Belgium

In the wake of the 1940 invasion, Germany established the Reichskommissariat of Belgium and Northern France to govern Belgium. United States, Canadian, British, and other Allied forces ended the Nazi occupation of most of Belgium in September of 1944. The Belgian Government in Exile under Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot returned on 8 September.[27]

In December, American forces suffered over 80,000 casualties defending Belgium from a German counterattack in the Battle of the Bulge. By February of 1945, all of Belgium was in Allied hands.[28]

The year 1945 was chaotic. Pierlot resigned, and Achille Van Acker of the Belgian Socialist Party formed a new government. There were riots over the Royal Question -- the return of King Leopold III. Although the war continued, Belgians were again in control of their own country.[29]

1945-49: Germany

The United States took part in the Denazification of the Western portion of Germany. Former Nazis were subjected to varying levels of punishment, depending on what the US thought of their levels of guilt. Eisenhower initially estimated that the process would take 50 years.[30] Depending on a former Nazi's level of culpability, punishments could range from a fine (for those judged least culpable), to denial of permission to work as anything but a manual laborer, to imprisonment and even death for the most severe offenders, such as those convicted in the Nuremberg Trials. At the end of 1947, for example, the Allies held 90,000 Nazis in detention; another 1,900,000 were forbidden to work as anything but manual labourers.[31]

As Germans took more and more responsibility for Germany, they pushed for an end to the denazification process, and the Americans allowed this. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany, also known as West Germany, was formed and took responsibility for denazification. For most former Nazis, the process came to an end with amnesty laws passed in 1951.[32] The ultimate outcome of denazification was the creation of a parliamentary democracy in West Germany.[33]

1945-55: Austria

Austria was annexed to Germany in the 1938 Anschluss. As German citizens, many Austrians fought on the side of Germany during World War 2. After the Allied victory, the Allies treated Austria as a victim of Nazi aggression, rather than as a perpetrator. The United States Marshall Plan provided aid.[34]

The 1955 Austrian State Treaty re-established Austria as a free, democratic, and sovereign state. It was signed by representatives of the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. It provided for the withdrawal of all occupying troops and guaranteed Austrian neutrality in the Cold War.[35]

1945-52: Japan

After the Allied victory in World War 2, Japan was occupied by Allied forces under the command of Douglas McArthur. In 1946, the Japanese Diet ratified a new Constitution of Japan that followed closely a 'model copy' prepared by McArthur's command,[36] and was promulgated as an amendment to the old Prussian-style Meiji Constitution. The constitution renounced aggressive war and was accompanied by liberalization of many areas of Japanese life.

While liberalizing life for most Japanese, the Allies tried many Japanese war criminals and executed some, while granting amnesty to the family of Emperor Hirohito.[37]

The occupation was ended by the Treaty of San Francisco.[37] It laid the groundwork for the Japanese economic miracle. Japanese industrial production had fallen in 1946 to 27.6% of the pre-war level, but regained this pre-war level in 1951 and reached 350% in 1960.[38]

1945–1953: South Korea

The Empire of Japan surrendered to the United States in August 1945, ending the brutal Japanese rule of Korea. Under the leadership of Lyuh Woon-Hyung committees throughout Korea formed to coordinate transition to Korean independence. On August 28, 1945 these committees formed the temporary national government of Korea, naming it the People's Republic of Korea (PRK) a couple of weeks later.[39][40] On September 8, 1945, the United States government landed forces in Korea and thereafter established the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGK) to govern Korea south of the 38th parallel north. The USAMGK outlawed the PRK government. The military governor Lieutenant-General John R. Hodge later said that "one of our missions was to break down this Communist government".[41][42]

In May 1948, Syngman Rhee, who had previously lived in the United States, won the election for President, which had been boycotted by most other politicians.[43]

On 25 June 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. Hundreds of thousands of South Koreans fled South. The Korean War ensued, with American and other United Nations supporting the South. United States forces suffered over 30,000 dead in the war. A 1953 armistice ended the war.[44]

1941–1949: China

On 1 August 1941, the United States, angered by Japanese atrocities in the second Sino-Japanese War, imposed an oil embargo on Japan. This led to the Attack on Pearl Harbor, getting the United States to join the Allies in World War 2. The U.S. government provided military, logistical and other aid to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) army led by Chiang Kai-shek in its campaign against the Japanese, until the Japanese surrender to the United States in August of 1945. This surrender brought to an end the Japanese Puppet state of Manchukuo and the Japanese-dominated Wang Jingwei regime.[45]

After the Japanese surrender, the US continued to support the KMT. The US airlifted many KMT troops from central China to Manchuria. Approximately 50,000 U.S. troops were sent to guard strategic sites in Hupeh and Shandong. The U.S. trained and equipped KMT troops, and transported Korean troops and even enemy imperial Japanese troops back to help KMT forces to occupy Chinese zones and to contain Communist-controlled areas.[46] President Harry Truman explained that: "It was perfectly clear to us that if we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the Communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison until we could airlift Chinese National troops to South China and send Marines to guard the seaports."[47] Within less than two years after the Sino-Japanese War, the KMT had received $4.43 billion from the United States—most of which was military aid.[46][48]

1944–1949: Greece

In August of 1944, German forces retreated from Greece because Allied military pressure, ending the Axis occupation of Greece.

The British military together with Greek forces under control of the Greek government fought for control of the country in the Greek Civil War against the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE). The DSE was composed mostly of communist partisans who as part of the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) by Summer 1944 had liberated nearly all of the country from the military occupation of the Third Reich.[49] By early 1947, the British government could no longer afford the huge cost of financing the war against DSE, and pursuant to the October 1944 Percentages Agreement between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin, Greece was to remain part of the Western sphere of influence. Accordingly, the British requested the US government to step in and the U.S. flooded the country with military equipment, military advisers and weapons.[50]: 553–554 [51]: 129 [52][53] With increased U.S. military aid, by September 1949 the Greek government eventually succeeded in winning.[54]: 616–617

1944– 1954: Philippines

United States landings in 1944 ended the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[55] After the Japanese were defeated, Sergio Osmeña formed a filipino government.

The United States helped defeat the pro-communist peasant uprising, called the Hukbalahap Rebellion, or Huk Rebellion.[56]

Cold War Era

1950s

1952: Egypt

Project FF (the "FF" standing for "Fat Fucker") was a CIA program initially designed to modernize the Kingdom of Egypt under Farouk I, pulling Egypt into the anti-soviet camp. However, the unwillingness of the king to comply led Kermit Roosevelt Jr. to support efforts to replace the regime entirely. Upon hearing rumors of discontent within the Egyptian military, Roosevelt met with the leaders of the nationalist, anti-communist, Free Officers Movement, most notably future Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, and informed them of American support for their imminent coup d'état. On July 23, 1952, the Free Officers Movement toppled the monarchy and established the Republic of Egypt.[57]

1943–1970s: Italy

British and United States military pressure led the King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy to dismiss Benito Mussolini in July of 1943. The king replaced him with Pietro Badoglio, who then made peace with the Allies. The Germans responded by taking control of much of Italy and forming the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state. The region controlled by the Social Republic shrank under the continuing Allied military campaign, surrendering on 1 May 1945.[58]

In 1947, the US-backed Christian Democrats (DC), led by Alcide De Gasperi, were losing popularity, and the Communist Party of Italy (PCI) was growing particularly fast due to its organizing efforts supporting sharecroppers in Sicily, Tuscany and Umbria, movements which were also bolstered by the reforms of Fausto Gullo, the Communist minister of agriculture.[59] The DC engineered the expulsion of all left-wing ministers from the cabinet on May 31. The PCI would not have a national position in government again for twenty years. De Gasperi did this under pressure from US Secretary of State George Marshall, who'd informed him that anti-communism was a pre-condition for receiving American aid,[60][61] and Ambassador James C. Dunn who had directly asked de Gasperi to dissolve the parliament and remove the PCI.[62]

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) acknowledged giving $1 million to Italian centrist parties for the 1948 election. The CIA also publishing forged letters in order to discredit the leaders of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). U.S. agencies undertook a campaign of writing ten million letters, made numerous short-wave radio broadcasts and funded the publishing of books and articles, all of which warned the Italians of what was believed to be the consequences of a communist victory. Time magazine backed the campaign for U.S. domestic audiences, featuring the Christian Democracy Party leader and Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi on its cover and in its lead story on April 19, 1948.[63][64][65][66] Meanwhile the US secretly convinced the British Labour Party to pressure social democrats to end their support for PCI, and foster a devastating split in the Italian Socialist Party.[67]

CIA ultimately spent at least $65 million helping elect Italian politicians,[68] including "every Christian Democrat who ever won a national election in Italy."[69]

1949: Syria

The democratically elected government of Shukri al-Quwatli was overthrown by a junta led by the Syrian Army chief of staff at the time, Husni al-Za'im, who became President of Syria on April 11, 1949. Za'im had extensive connections to CIA operatives,[70] although the exact nature of U.S. involvement in the coup remains highly controversial.[71][72][73] The construction of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, which had been held up in the Syrian parliament, was approved by Za'im, the new president, just over a month after the coup.[74]

1953: Iran

The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, (known in Iran as the "28 Mordad coup"[75]) was the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh on August 19, 1953, orchestrated by the intelligence agencies of the United Kingdom (under the name "Operation Boot") and the United States (under the name "TPAJAX Project").[76][77][78][79]. The coup saw the transition of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from a constitutional monarch to an authoritarian one who relied heavily on United States government support to hold on to power until his own overthrow in February 1979.[80]

1954: Guatemala

In a CIA operation code named Operation PBSUCCESS, the U.S. government executed a coup that was successful in overthrowing the democratically-elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz and installed Carlos Castillo Armas, the first of a line of brutal right-wing dictators, in its place.[81][82][83] The perceived success of the operation made it a model for future CIA operations because the CIA lied to the president of the United States when briefing him regarding the number of casualties.[84]

1955–1960: Laos

The U.S. government took over funding of the military budget of the Royal Lao Government in its civil war against the Pathet Lao communist movement, which had taken control of a part of the country. The US paid for 100% of the government's military budget and by 1957 was paying the salaries of the Royal Lao Army. Also the US set up the covert Programs Evaluation Office to field US civilian personnel with former US military experience because a treaty the US had signed expressly forbade US military advisors.[85][86] By July 1959 however, the US sent in US commando units dressed as civilians to train the Royal Lao Army.[87] These interventions did not result in regime change.

Failed coup plots against Syria

- 1956 Operation Straggle failed coup plot against Syria. The CIA made plans for a coup for late October 1956 to topple the Syrian government. The plan entailed takeover by the Syrian military of key cities and border crossings.[88][89][90] The plan was postponed when Israel invaded Egypt in October 1956 and US planners thought their operation would be unsuccessful at a time when the Arab world is fighting "Israeli aggression." The operation was uncovered and American plotters had to flee the country.[91]

- 1957 Operation Wappen failed coup plan against Syria. A second coup attempt the following year called for assassination of key senior Syrian officials, staged military incidents on the Syrian border to be blamed on Syria and then to be used as pretext for invasion by Iraqi and Jordanian troops, an intense US propaganda campaign targeting the Syrian population, and "sabotage, national conspiracies and various strong-arm activities" to be blamed on Damascus.[92][93][90][94] This operation failed when Syrian military officers paid off with millions of dollars in bribes to carry out the coup revealed the plot to Syrian intelligence. The U.S. Department of State denied accusation of a coup attempt and along with US media accused Syria of being a "satellite" of the USSR.[93][95][96]

1957–1959: Indonesia

As a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement and host of the April 1955 Bandung Conference, Indonesia was charting a course toward an independent foreign policy that was not militarily committed to either side in the Cold War.[97][98] Starting in 1957, the CIA supported a failed coup plan by rebel Indonesian military officers. CIA pilots, such as Allen Lawrence Pope, piloted planes operated by CIA front organization Civil Air Transport (CAT) that bombed civilian and military targets in Indonesia. The CIA instructed CAT pilots to target commercial shipping in order to frighten foreign merchant ships away from Indonesian waters, thereby to weaken the Indonesian economy and thus to destabilize the democratically elected government of Indonesia. The CIA aerial bombardment resulted in the sinking of several commercial ships[99] and the bombing of a marketplace that killed many civilians.[100] The coup attempt failed at that time[101] and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower denied any US involvement.[102]

1958: Lebanon

The U.S. launched Operation Blue Bat in July 1958 to intervene in the 1958 Lebanon crisis. This was the first application of the Eisenhower Doctrine, according to which the U.S. was to intervene to protect regimes it considered threatened by international communism. The goal of the operation was to bolster the pro-Western Lebanese government of President Camille Chamoun against internal opposition and threats from Syria and Egypt.[citation needed]

1959: Iraq

Richard Sale of United Press International, citing Adel Darwish and other experts, has reported that the October 1959 assassination attempt on Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim involving a young Saddam Hussein and other Ba'athist conspirators was a collaboration between the CIA and Egyptian intelligence.[103] Bryan R. Gibson has challenged the veracity of Sale and Darwish, citing declassified documents that indicate the CIA was blindsided by the timing of the assassination attempt on Qasim and that the National Security Council "had just reaffirmed [its] nonintervention policy" six days before it occurred.[104] Although the assassination attempt failed after Saddam (who was only supposed to provide cover) opened fire on Qasim—forcing Saddam to spend more than three years in exile in the Egyptian-led United Arab Republic (UAR) under threat of death if he returned to Iraq—it led to widespread exposure for Saddam and the Ba'ath within Iraq, where both had previously languished in obscurity, and later became a crucial part of Saddam's public image during his tenure as President of Iraq.[105][106] It is possible that Saddam visited the U.S. embassy in Cairo during his exile.[107]

1960s

1960: Democratic Republic of Congo

In January of 1961, D.R. Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba was killed by the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko in a coup orchestrated by United States CIA activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo under the Eisenhower administration, as a result of fears surrounding the Prime Minister’s budding relationships with Soviet and Chinese governments. Mobutu subsequently instituted a totalitarian regime whose actions contributed to the country’s present day war-ridden, impoverished state.

1960: Laos

On August 9, 1960, Captain Kong Le with his paratroop battalion seized control of the administrative capital city of Vientiane in a bloodless coup on a "Neutralist" platform with the stated aims of ending the civil war raging in Laos, ending foreign interference in the country, ending the corruption caused by foreign aid, and better treatment for soldiers.[108][109] With CIA support, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the prime minister of Thailand, set up a covert Thai military advisory group, called Kaw Taw. Kaw Taw together with the CIA orchestrated a November 1960 counter-coup against the new Neutralist government in Vientiane, supplying artillery, artillerymen, and advisers to General Phoumi Nosavan, first cousin of Sarit. It also deployed the CIA-sponsored Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU) to operations within Laos.[110] With the help of CIA front organization Air America to airlift war supplies and with other U.S. military assistance and covert aid from Thailand, General Phoumi Nosavan's forces captured Vientiane in November 1960.[111][112]

1961: Dominican Republic

In May 1961, the ruler of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo was murdered with weapons supplied by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). [113][114] An internal CIA memorandum states that a 1973 Office of Inspector General investigation into the murder disclosed "quite extensive Agency involvement with the plotters." The CIA described its role in "changing" the government of the Dominican Republic as a 'success' in that it assisted in moving the Dominican Republic from a totalitarian dictatorship to a Western-style democracy."[115][116] Juan Bosch, an earlier recipient of CIA funding, was elected president of the Dominican Republic in 1962, and was deposed in 1963.[117]

1961: Bay of Pigs

The CIA orchestrated a force composed of CIA-trained Cuban exiles to invade Cuba with support and equipment from the US military, in an attempt to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The invasion was launched in April 1961, three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in the United States. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the invading combatants within three days.

1960s: Cuba

Operation MONGOOSE was a years' long US government effort to overthrow the government of Cuba.[118] The operation included economic warfare, including an embargo against Cuba, "to induce failure of the Communist regime to supply Cuba's economic needs," a diplomatic initiative to isolate Cuba, and psychological operations "to turn the peoples' resentment increasingly against the regime."[119] The economic warfare prong of the operation also included the infiltration of CIA operatives to carry out many acts of sabotage against civilian targets, such as a railway bridge, a molasses storage facilities, an electric power plant, and the sugar harvest, notwithstanding Cuba's repeated requests to the United States government to cease its armed operations.[120][119] In addition, the CIA orchestrated a number of assassination attempts against Fidel Castro, head of government of Cuba, including attempts that entailed CIA collaboration with the American mafia.[121][122][123]

1961–1964: Brazil

When the president of Brazil resigned in August 1961, he was lawfully succeeded by João Belchior Marques Goulart, the democratically elected vice president of the country.[124] João Goulart was a proponent of democratic rights, the legalization of the Communist Party, and economic and land reforms, but the US government insisted that he impose a program of economic austerity. The United States government implemented a plan with the code name Operation Brother Sam for the destabilization of Brazil, by cutting off aid to the Brazilian government, providing aid to state governors of Brazil who opposed the new president, and encouraging senior Brazilian military officers to seize power and to back army chief of staff General Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco as coup leader.[125][126] General Branco led the April 1964 overthrow of the constitutional government of President João Goulart and was installed as first president of the military regime, immediately declaring a state of siege and arresting more than 50,000 political opponents within the first month of seizing power, while the US government expressed approval and re-instituted aid and investment in the country.[127]

1963: Iraq

Several sources, notably Said Aburish, have alleged that the February 1963 coup that resulted in the formation of a Ba'athist government in Iraq was "masterminded" by the CIA.[128] However, no declassified U.S. documents have verified this allegation.[129] Tareq Y. Ismael, Jacqueline S. Ismael, and Glenn E. Perry state that "Ba'thist forces and army officers overthrew Qasim on February 8, 1963, in collaboration with the CIA."[130] Conversely, Gibson argues that "the preponderance of evidence substantiates the conclusion that the CIA was not behind the February 1963 B'athist coup."[131] The U.S. offered material support to the new Ba'athist government after the coup, despite a bloody anti-communist purge and Iraqi atrocities against Kurdish rebels and civilians.[132] Because of this, Nathan Citino asserts: "Although the United States did not initiate the 14 Ramadan coup, at best it condoned and at worst it contributed to the violence that followed."[133] The Ba'athist government collapsed in November 1963 over the question of unification with Syria (where a rival branch of the Ba'ath Party had seized power in March).[134] There has been a great deal of academic discussion regarding allegations from King Hussein of Jordan and others that the CIA (or other U.S. agencies) provided the Ba'athist government with lists of communists and other leftists, who were then arrested or killed by the Ba'ath Party's militia—the National Guard. Gibson and Hanna Batatu emphasize that the identities of Iraqi Communist Party members were publicly known and that the Ba'ath would not have needed to rely on U.S. intelligence to identify them, whereas Citino considers the allegations plausible because the U.S. embassy in Iraq had actually compiled such lists, and because Iraqi National Guard members involved in the purge received training in the U.S.[135][136][137]

1963: Vietnam

Although the United States was allied with South Vietnam during the Vietnam War, the Kennedy administration had grown increasingly frustrated with South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem's corrupt and repressive rule. In light of Diem's refusal to adopt reforms, American officials debated whether they should support efforts to replace him. These debates resulted in the dispatch of Cable 243 on August 24, 1963, which instructed United States Ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., to "examine all possible alternative leadership and make detailed plans as to how we might bring about Diem's replacement if this should become necessary". Lodge and his liaison officer, Lucien Conein, established contact with discontented Army of the Republic of Vietnam officers and stimulated their resolve to overthrow Diem. These efforts culminated in a coup d'etat on November 2, 1963, during which Diem and his brother were assassinated.[138]

The Pentagon Papers concluded that "Beginning in August of 1963 we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government. In October we cut off aid to Diem in a direct rebuff, giving a green light to the generals. We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans and proposed new government."[139]

1965–66: Dominican Republic

In the Dominican Civil War, a junta led by President Joseph Donald Reid Cabral was battling "constitutionalist" or "rebel" forces who advocated restoring to power the Dominican Republic's first ever democratically elected president, President Juan Emilio Bosch Gaviño, whose term had been cut short by a coup. The U.S. launched "Operation Power Pack," a US military operation to interpose the US military between the rebels and the junta's forces so as to prevent the rebel's advance and possibly victory.[140][141] Most civilian advisers had recommended against immediate intervention hoping that the junta could bring an end to the civil war but US President Lyndon B. Johnson took the advice of his Ambassador in Santo Domingo, William Tapley Bennett, who suggested that the US intervene.[142] Chief of Staff General Wheeler told a subordinate: "Your unannounced mission is to prevent the Dominican Republic from going Communist."[143] A fleet of 41 US vessels was sent to blockade the island as the US invaded. Ultimately, 42,000 soldiers and marines were ordered to the Dominican Republic and the US occupied the country.[144]

1965–1967: Indonesia

Junior army officers and the commander of the palace guard of President Sukarno accused senior Indonesian military brass of planning a CIA-backed coup against President Sukarno and killed six senior generals on October 1, 1965. General Muhammad Suharto and other senior military officers attacked the junior officers on the same day and accused the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) of orchestrating the killing of the six generals.[145] The army launched a propaganda campaign based on lies and riled up civilian mobs to attack those believed to be PKI supporters and other political opponents. Indonesian government forces with collaboration of some civilians perpetrated mass killings over many months. The CIA acknowledged that "in terms of the number of people killed, the anti-PKI massacres in Indonesia rank as one of the worst mass murders of the 20th Century."[146] Estimates of the number of civilians killed range from a half million to a million[147][148][149] but more recent estimates put the figure at two to three million.[150][151] US Ambassador Marshall Green encouraged the military leaders to act forcefully against the political opponents.[146] In 2017, declassified documents from the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta have confirmed that the US had detailed, ongoing knowledge of the mass killings and actively facilitated and encouraged them for its own geopolitical interests.[152][153][154][155] US diplomats admitted to journalist Kathy Kadane in 1990 that they had provided the Indonesian army with thousands of names of alleged PKI supporters and other alleged leftists, and that the U.S. officials then checked off from their lists those who had been murdered.[156][157] President Sukarno's base of support was largely annihilated, imprisoned and the remainder terrified, and thus he was forced out of power in 1967, replaced by an authoritarian military regime led by General Suharto.[158][159] Some scholars are now referring to the mass killings as a genocide.[160][161][162]

1967: Greece

On 21 April 1967, just weeks before the scheduled elections, a group of right-wing army officers led by Brigadier General Stylianos Pattakos and Colonels George Papadopoulos and Nikolaos Makarezos seized power in a coup d'etat.[163] The coup leaders placed tanks in strategic positions in Athens, effectively gaining complete control of the city.

At the same time, a large number of small mobile units were dispatched to arrest leading politicians, authority figures, and ordinary citizens suspected of left-wing sympathies, according to lists prepared in advance. One of the first to be arrested was Lieutenant General Grigorios Spandidakis, Commander-in-Chief of the Greek Army. The colonels persuaded Spandidakis to join them, having him activate a previously-drafted action plan to move the coup forward. By the early morning hours, the whole of Greece was in the hands of the colonels. All leading politicians, including acting Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, had been arrested and were held incommunicado by the conspirators. At 6:00 a.m. EET, Papadopoulos announced that eleven articles of the Greek constitution were suspended.[164]

The left of center Center Union Party founder, Georgios Papandreou was arrested after a nighttime raid at his villa in Kastri, Attica. Andreas was arrested at around the same time, after seven soldiers armed with fixed bayonets and a machine gun forcibly entered his home. Andreas Papandreou escaped to the roof of his house, but surrendered after one of the soldiers held a gun to the head of his then-fourteen-year-old son George Papandreou.[164] Gust Avrakotos, a high-ranking CIA officer in Greece who was close with the colonels, allegedly advised them to "shoot the motherfucker because he's going to come back to haunt you".[165]

U.S. critics of the coup included then-Senator Lee Metcalf, who criticised the Johnson Administration for providing aid to a "military regime of collaborators and Nazi sympathisers". Phillips Talbot, the U.S. ambassador in Athens, disapproved of the coup, complaining that it represented "a rape of democracy", to which John M. Maury, the CIA station chief in Athens, answered, "How can you rape a whore?"[164] The CIA claims the timing of the coup apparently caught the agency by surprise.[166]

1970s

1971: Bolivia

The U.S. government supported the 1971 coup led by General Hugo Banzer that toppled President Juan José Torres of Bolivia.[167][168] Torres had displeased Washington by convening an "Asamblea del Pueblo" (People's Assembly or Popular Assembly), in which representatives of specific proletarian sectors of society were represented (miners, unionized teachers, students, peasants), and more generally by leading the country in what was perceived as a left wing direction. Banzer hatched a bloody military uprising starting on August 18, 1971 that succeeded in taking the reigns of power by August 22, 1971. After Banzer took power, the U.S. provided extensive military and other aid to the Banzer dictatorship as Banzer cracked down on freedom of speech and dissent, tortured thousands, "disappeared" and murdered hundreds, and closed labor unions and the universities.[169][170] Torres, who had fled Bolivia, was kidnapped and assassinated in 1976 as part of Operation Condor, the US-supported campaign of political repression and state terrorism by South American right-wing dictators.[171][172][173]

1972–1975: Iraq

The U.S. secretly provided millions of dollars for the Kurdish insurgency supported by Iran against the Iraqi government.[174][175] The U.S. role was so secret even the US State Department and the U.S. "40 Committee," created to oversee covert operations, were not informed. The troops of the Kurdish Democratic Party were led by Mustafa Barzani. Notably, unbeknownst to the Kurds, this was a covert regime change action the US wanted to fail, intended only to drain the resources of the country.[176][177] The U.S. abruptly ceased support for the Kurds in 1975 and, despite Kurdish pleas for help, refused to extend even humanitarian aid to the thousands of Kurdish refugees created as a result of the collapse of the insurgency.[178][179]

1973: Chile

The democratically elected President Salvador Allende was overthrown by the Chilean armed forces and national police. This followed an extended period of social and political unrest between the right dominated Congress of Chile and Allende, as well as economic warfare waged by the U.S. government.[180] As a prelude to the coup, the chief of staff of the Chilean army, René Schneider, a general dedicated to preserving the constitutional order, was assassinated in 1970 during a botched kidnapping attempt backed by the CIA.[181][182] The regime of Augusto Pinochet that came to power with the coup is notable for having, by conservative estimates, disappeared some 3200 political dissidents, imprisoned 30,000 (many of whom were tortured), and forced some 200,000 Chileans into exile.[183][184][185] The CIA, through Project FUBELT (also known as Track II), worked secretly to engineer the conditions for the coup. The U.S. initially denied any involvement however many relevant documents have been declassified in the decades since.[186]

1979–1989: Afghanistan

In what was known as "Operation Cyclone," the U.S. government secretly provided weapons and funding for a collection of warlords and several factions of Jihadi guerillas known as the Mujahideen of Afghanistan fighting to overthrow the Afghan government and the Soviet military forces that supported it. Through the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan, the US channeled training, weapons and money for Afghan fighters, including jihadis who later became known as the Taliban, and at an estimated cost of $800 million for as many as 35,000 Arab foreign fighters.[187][188][189][190] Afghan Arabs also "benefited indirectly from the CIA's funding, through the ISI and resistance organizations,"[191][192] Some of the CIA's greatest Afghan beneficiaries were Arabist commanders such as Jalaluddin Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar who were key allies of Osama Bin Laden over many years.[193][194][195] Some of the CIA-funded militants would become part of Al Qaeda later on, and included Osama Bin Laden, according to former Foreign Secretary Robin Cook and other sources.[196][197][198][199][200] However, these allegations are rejected by Steve Coll ("If the CIA did have contact with bin Laden during the 1980s and subsequently covered it up, it has so far done an excellent job"),[201] Peter Bergen ("The theory that bin Laden was created by the CIA is invariably advanced as an axiom with no supporting evidence"),[202] and Jason Burke ("It is often said that bin Laden was funded by the CIA. This is not true, and, indeed, would have been impossible given the structure of funding that General Zia ul–Haq, who had taken power in Pakistan in 1977, had set up").[203] Although Operation Cyclone officially ended in 1989 with the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, U.S. government funding for the Mujahideen continued through 1992, when the Mujahideen overran the Afghan government in Kabul.[204]

1980s

1980-1989: Poland

Unlike the Carter Administration, the Reagan policies supported the Solidarity movement in Poland, and—based on CIA intelligence—waged a public relations campaign to deter what the Carter administration felt was "an imminent move by large Soviet military forces into Poland."[205] Michael Reisman from Yale Law School named operations in Poland as one of the covert actions of CIA during Cold War.[206] Colonel Ryszard Kukliński, a senior officer on the Polish General Staff was secretly sending reports to the CIA.[207] The CIA transferred around $2 million yearly in cash to Solidarity, for a total of $10 million over five years. There were no direct links between the CIA and Solidarnosc, and all money was channeled through third parties.[208] CIA officers were barred from meeting Solidarity leaders, and the CIA's contacts with Solidarnosc activists were weaker than those of the AFL-CIO, which raised $300,000 from its members, which were used to provide material and cash directly to Solidarity, with no control of Solidarity's use of it. The U.S. Congress authorized the National Endowment for Democracy to promote democracy, and the NED allocated $10 million to Solidarity.[209]

When the Polish government launched martial law in December 1981, however, Solidarity was not alerted. Potential explanations for this vary; some believe that the CIA was caught off guard, while others suggest that American policy-makers viewed an internal crackdown as preferable to an "inevitable Soviet intervention."[210] CIA support for Solidarity included money, equipment and training, which was coordinated by Special Operations.[211] Henry Hyde, U.S. House intelligence committee member, stated that the USA provided "supplies and technical assistance in terms of clandestine newspapers, broadcasting, propaganda, money, organizational help and advice".[212] Initial funds for covert actions by CIA were $2 million, but soon after authorization were increased and by 1985 CIA successfully infiltrated Poland.[213]

1980–1992: El Salvador

The government of El Salvador fought a bloody civil war against the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), an umbrella organization of leftist political opposition groups, and against leaders of agricultural cooperatives, labor leaders and others who advocated for land reform and better conditions for "campesinos" (tenant farmers and other agrarian laborers) that supported the FMLN. The Salvadoran army organized military death squads to terrorize the rural civil population to cease its support for the FMLN.[214] Government forces killed more than 75,000 civilians during the war 1980–1992.[215][216][217][218][219][220] The U.S. government provided military training and weapons for the Salvadoran military. The Atlacatl Battalion, a counter-insurgency battalion, was organized in 1980 at the US Army School of the Americas and had a leading role in the "scorched earth" military policy against the FLMN and the rural villages that supported it. Atlacatl soldiers were equipped and directed by U.S. military advisers operating in El Salvador.[221][222][223] The Atlacatl battalion also participated in the El Mozote massacre in December 1981.[224] By May 1983, US officers took over positions in the top levels of the Salvadoran military, were making critical decisions and running the war.[225][226][227][228] A US Congressional fact finding commission found that the Salvadoran military's "drying up the ocean" policy of repression entailed eliminating "entire villages from the map, to isolate the guerrillas, and deny them any rural base off which they can feed."[229] The "drying up the ocean" or "scorched earth" strategy was based on tactics similar to those being employed by the junta's counter-insurgency in neighboring Guatemala and were primarily derived and adapted from U.S. strategy during the Vietnam War and taught by American military advisors.[230][231]

1982–1989: Nicaragua

The U.S. government attempted to topple the government of Nicaragua by secretly arming, training and funding the Contras, a rebel group based in Honduras that was created to sabotage Nicaragua and to destabilize the Nicaraguan government.[232][233][234][235] As part of the training, the CIA distributed a detailed "terror manual" entitled "Psychological Operations in Guerrilla War," which instructed the Contras, among other things, on how to blow up public buildings, to assassinate judges, to create martyrs, and to blackmail ordinary citizens.[236] In addition to orchestrating the Contras, the U.S. government also blew up bridges and mined Corinto harbor, causing the sinking of several civilian Nicaraguan and foreign ships and many civilian deaths.[237][238][239][240] After the Boland Amendment made it illegal for the U.S. government to provide funding for Contra activities, the administration of President Reagan secretly sold arms to the Iranian government to fund a secret U.S. government apparatus that continued illegally to fund the Contras, in what became known as the Iran-Contra affair.[241] The U.S. continued to arm and train the Contras even after the Sandinista government of Nicaragua won the elections of 1984.[242][243]

1983: Grenada

In what the U.S. government called Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. military invaded the tiny island nation of Grenada to remove the Marxist government of Grenada that the Reagan Administration found objectionable.[244][245] The United Nations General Assembly called the U.S. invasion "a flagrant violation of international law"[246] but a similar resolution widely supported in the United Nations Security Council was vetoed by the U.S.[247][248]

1989: Panama

In December 1989, in a military operation code-named Operation Just Cause, the U.S. invaded Panama. President George H. W. Bush launched the war ten years after the Torrijos–Carter Treaties were ratified to transfer control of the Panama Canal from the United States to Panama by the year 2000. The U.S. deposed de facto Panamanian leader, general, and dictator Manuel Noriega and brought him to the United States, president-elect Guillermo Endara was sworn into office, and the Panamanian Defense Force was dissolved.

Post-Cold War

1990s

1991: Kuwait

After Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, the US government strenuously lobbied governments represented on the UN Security Council to support a resolution authorizing UN members states to use "all necessary means" for removing Iraqi forces from Kuwait.[249] UN Security Council Resolution 678, including such language, was passed and the US assembled a 34 state coalition force to invade. The operation was launched in January 1991 and had US code name "Operation Desert Storm." The U.S.-led coalition repelled the Iraqi forces from Kuwait and returned to power the emir, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah.[250]

1991: Haiti

- 1991 Haiti. Eight months after what was widely considered the first honest election held in Haiti,[citation needed] the newly elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was deposed by the Haitian army. It is alleged by some that the CIA "paid key members of the coup regime forces, identified as drug traffickers, for information from the mid-1980s at least until the coup."[251] Coup leaders Cédras and François had received military training in the United States.[252]

1991–2003: Iraq

Following the Persian Gulf War in 1991, the U.S. government successfully advocated that the pre-war sanctions[253] be made more comprehensive, which the UN Security Council did in April 1991 by adopting Resolution 687.[254][255] After the UN imposed the tougher sanctions, U.S. officials stated in May 1991—when it was widely expected that the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein faced collapse[256][257]—that the sanctions would not be lifted unless Saddam was ousted.[258][259][260] In the subsequent president's administration, U.S. officials took the position that the sanctions could be lifted if Iraq complied with all of the UN resolutions it was violating, not just with UN weapons inspections.[261] The effects of the sanctions on the Iraqi civilian population, including the child mortality rate, were disputed at the time. Whereas it was widely believed at the time that the sanctions caused a major rise in child mortality, recent research has shown that commonly cited data were fabricated by the Iraqi government and that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after 1990 and during the period of the sanctions."[262][263][264][265][266]

1994–2000: Iraq

The CIA launched DBACHILLES, a coup d'état operation against the Iraqi government, recruiting Ayad Allawi, who headed the Iraqi National Accord, a network of Iraqis who opposed the Saddam Hussein government, as part of the operation. The network included Iraqi military and intelligence officers but was penetrated by people loyal to the Iraqi government.[267][268][269] Also using Ayad Allawi and his network, the CIA directed a government sabotage and bombing campaign in Baghdad between 1992 and 1995, against targets that—according to the Iraqi government at the time—killed many civilians including people in a crowded movie theater.[270] The CIA bombing campaign may have been merely a test of the operational capacity of the CIA's network of assets on the ground and not intended to be the launch of the coup strike itself.[270] The coup was unsuccessful, but Ayad Allawi was later installed as prime minister of Iraq by the Iraq Interim Governing Council, which had been created by the U.S.-led coalition following the March 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq. As a non-covert measure, the U.S. in 1998 enacted the "Iraq Liberation Act," which states, in part, that "It should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq," and appropriated funds for U.S. aid "to the Iraqi democratic opposition organizations."[271]

1997: Indonesia

The Clinton administration saw an opportunity to oust Indonesian President Suharto when his rule over Indonesia became increasingly precarious in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. American officials sought to exacerbate Indonesia's monetary crisis by having the International Monetary Fund oppose Suharto's efforts to establish a currency board to stabilize the rupiah, thereby provoking discontent. IMF Director Michel Camdessus boasted that, "We created the conditions that obliged President Suharto to leave his job". Former US Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger would later remark, "We were fairly clever in that we supported the IMF as it overthrew [Suharto]. Whether that was a wise way to proceed is another question. I'm not saying Mr. Suharto should have stayed, but I kind of wish he had left on terms other than because the IMF pushed him out."[272][273] Hundreds would die in the crisis that followed.

2000s

2000: Yugoslavia

From the period of 1998 to 2000, just over $100,000,000 was channeled from the U.S. State Department through Quangos to opposition parties in order to bring about regime change in Yugoslavia.[274] Following issues regarding the results of the Yugoslav elections of 2000, the U.S. State Department heavily supported opposition groups such as Otpor! through the supply of promotional material and also, consulting services via Quangos.[275] United States involvement served to speed up and organize dissent through exposure, resources, moral and material encouragement, technological aid and professional advice.[274] This campaign was one of the factors contributing to the Bulldozer Revolution and thus the overthrow of the long standing president Slobodan Milošević on October 5, 2000.[274]

2003: Iraq

2005: Iran

According to U.S. and Pakistani intelligence sources, beginning in 2005 the U.S. government secretly encouraged and advised a Pakistani Balochi militant group named Jundullah that is responsible for a series of deadly guerrilla raids inside Iran.[276] Jundullah, led by Abdolmalek Rigi (sometimes written as Abd el Malik Regi), also known as "Regi," was suspected of being associated with Al Qaeda, a charge that the group has denied. ABC News learned from tribal sources that money for Jundullah was routed to the group through Iranian exiles. "They are suspected of having links to Al Qaeda and they are also thought to be tied to the drug culture," according to Professor Vali Nasr.[277] U.S. intelligence sources later claimed that the orchestration of Jundallah operations was, in actuality, an Israeli Mossad (intelligence agency) false flag operation that Israeli agents disguised to make it appear to be the work of American intelligence.[278]

2006–07: Palestinian territories

The U.S. government pressured the Fatah faction of the Palestinian leadership to topple the Hamas government of Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh.[279][280][281] The Bush Administration was displeased with the government that the majority of the Palestinian people elected in the January Palestinian legislative election of 2006.[279][280][282] The U.S. government set up a secret training and armaments program that received tens of millions of dollars in Congressional funding, but also, like in the Iran-contra scandal, a more secret Congress-circumventing source of funding for Fatah to launch a bloody war against the Haniyeh government.[279][283][284] The war was brutal, with many casualties and with Fatah kidnapping and torturing civilian leaders of Hamas, sometimes in front of their own families, and setting fire to a university in Gaza. When the government of Saudi Arabia attempted to negotiate a truce between the sides so as to avoid a wide-scale Palestinian civil war, the U.S. government pressured Fatah to reject the Saudi plan and to continue the effort to topple the Haniyeh government.[279] Ultimately, the Haniyeh government was prevented from ruling over all of the Palestinian territories, with Hamas retreating to the Gaza strip and Fatah retreating to the West Bank.

Post–2005: Syria

Since 2006, the State Department has funneled at least $6 million to the anti-government satellite channel Barada TV, associated with the exile group Movement for Justice and Development in Syria. This secret backing continued under the Obama administration, even as the US publicly rebuilt relations with Bashar Al-Assad.[285][286]

After the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the U.S. government called on Syrian President Bashar Al Assad to "step aside" and imposed an oil embargo against the Syrian government to bring it to its knees.[287][288][289] Starting in 2013, the U.S. also provided training, weapons and cash to Syrian vetted "moderate" rebels,[290][291] and in 2014, the Supreme Military Council.[292][293]

In March 2017 Ambassador Nikki Haley told a group of reporters that the US's priority in Syria was no longer on "getting Assad out."[294] Earlier that day at a news conference in Ankara, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson also said that the "longer term status of President Assad will be decided by the Syrian people."[295] While the US Defense Department's program to aid predominantly Kurdish rebels fighting the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) continued, it was revealed in July 2017 that US President Trump had ordered a "phasing out" of the CIA's support for anti-Assad rebels.[296]

2010s

2011: Libya

The US was part of a multi-national coalition that undertook the 2011 military intervention in Libya to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which was taken in response to events during the Libyan Civil War,[297] and military operations began, with US and British naval forces firing over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles,[298] the French and British Air Forces[299] undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval blockade by Coalition forces.[300]

2015–present: Yemen

The U.S. has been supporting the intervention by Saudi Arabia in the Yemeni Civil War. The Yemeni Civil War began in 2015 between two sides, each claiming at that time to support the legitimate government of Yemen:[301] Houthi forces, which control the capital Sana'a and had supported former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, fighting against forces based in Aden and loyal to the government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.[302] The Saudi-led offensive is aimed at restoring Hadi to power, and is allied with various local factions.[303] The Saudi Arabian-led intervention has been widely condemned due to its widespread bombing of urban and other civilian areas, including schools and hospitals.[304][305][306] The U.S. military provides targeting assistance and intelligence and logistical support for the Saudi-led bombing campaign,[307] including aerial refueling.[308][309] The US also provides weapons and bombs,[310] including, according to a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, cluster bombs outlawed in much of the world and used by Saudi Arabia in the conflict.[311][312] The United States also supports the war effort on the ground with Green Berets on the Yemen border with Saudi Arabia tasked initially to help the Saudis secure the border and later expanded to help locate and destroy Houthi ballistic missile caches and launch sites in what Senator Tim Kaine called a “purposeful blurring of lines between train and equip missions and combat.”[313] The US has been criticized for providing weapons and bombs knowing that Saudi bombing has been indiscriminately targeting civilians and violating the laws of war.[314][315][316] It has been suggested that the U.S. government is legally a "co-belligerent" in the conflict, in which case U.S. military personnel could be prosecuted for war crimes,[317][318][319] and a U.S. senator has accused the U.S. of complicity in Yemen's humanitarian catastrophe, with millions facing starvation.[320][321] As of May 2018, the civil war is at a stalemate, and 13 million Yemeni civilians face starvation, according to the UN.[322]

Shortly after Hugo Chávez’s election to president in 1998, the U.S. government-funded National Endowment for Democracy (NED) initiated guidance of Venezuelan political parties towards his defeat. NED agents traveled to Venezuela and met individually with Venezuelan party leaders from the opposition, offering guidance on how to electorally defeat Chávez, construct coalition political platforms and reach out to youth. U.S. diplomats also met with the opposition over the course of a decade to advise strategy against Chavez.

Agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) initiated operations developing neutral-looking organizations in poor neighborhoods focused on community initiatives such as participatory democracy. U.S. ambassador William Brownfield described how USAID/OTI, “directly reached approximately 238,000 adults through over 3,000 forums…providing opportunities for opposition activists to interact with hardcore Chavistas, with the desired effect of pulling them slowly away from Chavismo.”

USAID/OTI also materially supported the recently developed anti-Chávez student movement, which produced the political career of Juan Guaidó and other young opposition leaders. OTI functionaries provided students with resources including paper and microphones, paid for travel expenses, and organized seminars to maximize resistance to the socialist government. According to a Washington Post analysis, “U.S. diplomats regularly met with opposition student leaders who primarily operated in Caracas, discussing plans of action against the Chávez government.”

The campaign against Venezuela’s left-leaning government continued under four US presidents. Most recently, the Trump administration has recognized the unelected opposition leader Juan Guaido as president and openly threatened to launch military action to overthrow the government of Nicolas Maduro.[323]

Covert involvements

During the modern era, Americans were involved in numerous covert regime change efforts. During the Cold War in particular, the U.S. government secretly supported military coups that overthrew democratically elected governments in Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, the Congo in 1960, Brazil in 1964 and Chile in 1973.

See also

- Criticism of United States foreign policy

- Foreign electoral intervention

- Foreign interventions by the United States

- Timeline of United States military operations

- United States involvement in regime change in Latin America

Notes

- ^ The Washington Post, October 13, 2016, "The Long History of the US Interfering with Elections Elsewhere," https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/10/13/the-long-history-of-the-u-s-interfering-with-elections-elsewhere/ Archived June 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ New York Times, February 17, 2019, "Russia Isn't the Only One Meddling in Elections, We Do It, Too," https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/17/sunday-review/russia-isnt-the-only-one-meddling-in-elections-we-do-it-too.html Archived February 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine citing Conflict Management and Peace Science, September 19, 2016 "Partisan Electoral Interventions by the Great Powers: Introducing the PEIG Dataset," http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0738894216661190

- ^ United Nations Foundation, August 20, 2015, "The American Ratification of the UN Charter," http://unfoundationblog.org/the-american-ratification-of-the-un-charter/ Archived September 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mansell, Wade and Openshaw, Karen, "International Law: A Critical Introduction," Chapter 5, Hart Publishing, 2014, https://books.google.com/booksid=XYrqAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT140

- ^ "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." United Nations, "Charter of the United Nations," Article 2(4), http://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chapter-i/index.html Archived October 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fox, Gregory, "Regime Change," 2013, Oxford Public International Law, Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Sections C(12) and G(53)–(55), Archived November 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bauer, K.J., 1974, The Mexican War, 1846–1848, New York: Macmillan, ISBN 0803261071

- ^ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1892). A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-4264-0754-3.

- ^ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975. (Reprint by special arrangement with Yale University Press. Originally published at New Haven: Yale University Press, 1928), p. 574; the Tripartite Convention (United States, Germany, Great Britain) was signed at Washington on December 2, 1899.