User:MacDaid/sandbox 1: Difference between revisions

add article for work here |

|||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

In 1949, despite protests from the medical establishment, the Portuguese neurologist [[Antonio Egas Moniz]] received the Physiology or Medicine Prize for his development of the [[prefrontal leucotomy]] which he promoted by misrepresenting the results, declaring the procedure's success just 10 days postoperative. Due largely to the publicity surrounding the award, it was prescribed without regard for modern [[medical ethics]]. Favorable results were reported by such publications as ''[[The New York Times]]''. It is estimated that around 5,000 lobotomies were performed between 1949 and 1952 in the United States, until the procedure's popularity faded. [[Joseph Kennedy]], the father of [[John Kennedy]] subjected his daughter, Rosemary, to the procedure which incapacitated her to the degree that she needed to be institutionalized for the rest of her life.<ref name="feldman"/><ref>{{cite news|last=Day|first=Elizabeth|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2008/jan/13/neuroscience.medicalscience |title=He was bad, so they put an ice pick in his brain... |work=The Guardian|publisher=Guardian Media Group |accessdate=31 March 2010|date=12 January 2008}}</ref> |

In 1949, despite protests from the medical establishment, the Portuguese neurologist [[Antonio Egas Moniz]] received the Physiology or Medicine Prize for his development of the [[prefrontal leucotomy]] which he promoted by misrepresenting the results, declaring the procedure's success just 10 days postoperative. Due largely to the publicity surrounding the award, it was prescribed without regard for modern [[medical ethics]]. Favorable results were reported by such publications as ''[[The New York Times]]''. It is estimated that around 5,000 lobotomies were performed between 1949 and 1952 in the United States, until the procedure's popularity faded. [[Joseph Kennedy]], the father of [[John Kennedy]] subjected his daughter, Rosemary, to the procedure which incapacitated her to the degree that she needed to be institutionalized for the rest of her life.<ref name="feldman"/><ref>{{cite news|last=Day|first=Elizabeth|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2008/jan/13/neuroscience.medicalscience |title=He was bad, so they put an ice pick in his brain... |work=The Guardian|publisher=Guardian Media Group |accessdate=31 March 2010|date=12 January 2008}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Rosalind Franklin.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Rosalind Franklin]] was never nominated for a Nobel Prize, despite her important work regarding the [[DNA#Discovery of the structure of DNA|structure of DNA]].<ref name="Fredholm"/>]] |

[[:File:Rosalind Franklin.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Rosalind Franklin]] was never nominated for a Nobel Prize, despite her important work regarding the [[DNA#Discovery of the structure of DNA|structure of DNA]].<ref name="Fredholm"/>]]<!--Non free file removed by DASHBot--> |

||

The 1952 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded solely to [[Selman Waksman]] for his discovery of [[streptomycin]] had omitted the recognition some felt due his co-discoverer [[Albert Schatz (scientist)|Albert Schatz]].<ref name="pharmj">[http://www.pharmj.com/pdf/articles/pj_20060225_streptomycin.pdf "Streptomycin: arrogance and anger]". by Steve Ainsworth pjonline.com</ref><ref name="Wainwright">Wainwright, Milton ''"A Response to William Kingston, "Streptomycin, Schatz versus Waksman, and the balance of Credit for Discovery""'', Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences – Volume 60, Number 2, April 2005, pp. 218–220, Oxford University Press.</ref> There was a litigation brought by Schatz against Waksman over the details and credit of streptomycin discovery. The litigation result was such that Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, together with Waksman, Schatz was be officially recognized as a co-discoverer of streptomycin as far as patent rights. However, he is not recognized as a Nobel Prize winner.<ref name="pharmj"/> |

The 1952 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded solely to [[Selman Waksman]] for his discovery of [[streptomycin]] had omitted the recognition some felt due his co-discoverer [[Albert Schatz (scientist)|Albert Schatz]].<ref name="pharmj">[http://www.pharmj.com/pdf/articles/pj_20060225_streptomycin.pdf "Streptomycin: arrogance and anger]". by Steve Ainsworth pjonline.com</ref><ref name="Wainwright">Wainwright, Milton ''"A Response to William Kingston, "Streptomycin, Schatz versus Waksman, and the balance of Credit for Discovery""'', Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences – Volume 60, Number 2, April 2005, pp. 218–220, Oxford University Press.</ref> There was a litigation brought by Schatz against Waksman over the details and credit of streptomycin discovery. The litigation result was such that Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, together with Waksman, Schatz was be officially recognized as a co-discoverer of streptomycin as far as patent rights. However, he is not recognized as a Nobel Prize winner.<ref name="pharmj"/> |

||

Revision as of 05:04, 23 June 2010

| The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Description | Outstanding contributions in Physiology or Medicine |

| Country | Sweden |

| Presented by | Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences |

| First awarded | 1901 |

| Website | http://nobelprize.org |

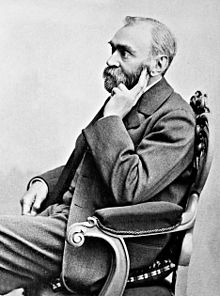

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (Template:Lang-sv) is awarded once a year by the Swedish Karolinska Institute for outstanding contributions in the field. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel (), the inventor of dynamite, in his will, the others being for contributions in Physics, Chemistry, Literature and Peace. Nobel was personally interested in experimental physiology and was very optimistic about the progress being made through scientific discoveries in laboratories. The award is administered by the Nobel Foundation and is widely regarded as the most prestigious award that a scientist can receive. It is presented to the recipient by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm at an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death, along with a diploma and a certificate for the monetary award. The front side of the medal provides the same profile of Alfred Nobel as depicted on the medals for Physics, Chemistry, and Literature; its reverse side is unique to this medal and represents the Genius of Medicine.

As of 2009, 100 Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to 195 individuals, 10 of them women. The first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded in 1901 to the German physiologist Emil Adolf von Behring, for his work on serum therapy and a vaccine against diphtheria, leading to the eradication of that disease in the industrialized world. Subsequent laureates have been chosen from a wide range of fields that relate to physiology or medicine. The first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Gerty Cori, received it in 1947. In 2009, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Elizabeth Blackburn, Carol W. Greider and Jack W. Szostak of the United States for the discovery of the role of telomeres and telomerase in protecting chromosomes; this is the first time two woman have won a Nobel Prize in the same year.

Some awards have been controversial, including one to Antonio Egas Moniz in 1949 for the prefrontal leucotomy, despite protests from the medical establishment. Other controversies resulted from disagreements over who was included in the award. The 1952 prize to Selman Waksman was litigated in court, and half the patent rights awarded to his co-discovered Albert Schatz who was not recognized by the prize. The 1962 prize awarded to James D. Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their work on DNA structure and properties did not acknowledge the contributing work from others, such as Oswald Avery and Rosalind Franklin who had died by the time of the nomination. Since the Nobel Prize rules forbid nominations of the deceased, longevity is an asset, one prize being awarded as long as 50 years after the discovery. Also forbidden is awarding any one prize to more than three recipients, and since in the last half century there has been an increasing tendency for scientists to work as teams, this rule has resulted in controversial exclusions.

Background

Alfred Nobel () was born on 21 October 1833 in Stockholm, Sweden, into a family of engineers.[1] He was a chemist, engineer, and inventor. In 1895 Nobel purchased the Bofors iron and steel mill, which he converted into a major armaments manufacturer. Nobel amassed a fortune during his lifetime, most of it from his 355 inventions, of which dynamite is the most famous.[2] In 1888, Alfred had the unpleasant surprise of reading his own obituary, titled ‘The merchant of death is dead’, in a French newspaper. As it was Alfred's brother Ludvig who had died, the obituary was eight years premature. Alfred was disappointed with what he read and concerned with how he would be remembered. This inspired him to change his will.[3] On 10 December 1896 Alfred Nobel died in his villa in San Remo, Italy, at the age of 63 from a cerebral haemorrhage.[4]

Nobel was greatly interested in experimental physiology and set up his own labs in France and Italy to conduct experiments in blood transfusions. He kept abreast of scientific findings and donated generously to Ivan Pavlov's laboratory in Russia. (Pavlov won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 for his work on the physiology of digestion.[5]) He was very optimistic about the progress being made through scientific discoveries in laboratories.[6] Nobel requested in his last will and testament that his money be used to create a series of prizes for those who confer the "greatest benefit on mankind" in physics, chemistry, peace, physiology or medicine, and literature.[7] Though Nobel wrote several wills during his lifetime, the last was written a little over a year before he died, and signed at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris on 27 November 1895.[8] Nobel bequeathed 94% of his total assets, 31 million Swedish kronor (US$186 million in 2008), to establish and endow the five Nobel Prizes.[9] Due to the level of skepticism surrounding the will it was not until April 26, 1897 that it was approved by the Storting (Norwegian Parliament).[10] The executors of his will were Ragnar Sohlman and Rudolf Lilljequist, who formed the Nobel Foundation to take care of Nobel's fortune and organise the prizes.[11]

The members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee that were to award the Peace Prize were appointed shortly after the will was approved. The prize-awarding organization selected for the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was the Karolinska Institutet.[12][13] The Nobel Foundation then reached an agreement on guidelines for how the Nobel Prize should be awarded. In 1900, the Nobel Foundation's newly created statutes were promulgated by King Oscar II.[14][10] According to Nobel's will, the Karolinska Institutet were to award the Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Nomination and selection

Nobel had selected the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, a body of 50 professors of the Karolinska Institute which is a medical school and research center, to choose the Nobel Laureates. The Institute declared that the prize would only go for achievements in basic research in human health, a decision which decisively connected the prize in medicine to the new field of medical laboratory research and ruled out awarding the prize for clinical achievements.[6] Per his will, only select persons are eligible to nominate individuals for the award. These include members of select academies in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland and Finland, as well as certain individuals affiliated with prestigious institutions in other lands. Past Nobel laureates may also nominate.[15] The working body of the Assembly involved in screening candidates is a Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine that consists of five members elected by the Karolinska Institutet's Nobel Assembly.[16] They are assisted by appointed expert advisers.[17] In its first stage, forms, which amount to a personal and exclusive invitation, are sent to about three thousand selected individuals to invite them to submit nominations. The names of the nominees are never publicly announced, and neither are they told that they have been considered for the Prize. Information about the nominations is not disclosed for 50 years.[16]

The nominations are screened by the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, and a list is produced of approximately two hundred preliminary candidates. This list is forwarded to selected experts in the field. They remove all but approximately fifteen names. The committee submits a report with recommendations to the Karolinska Institutet. While posthumous nominations are not permitted, awards did occur if the individual died in the months between the nomination and the decision of the prize committee. This rule was modified in 1974 to require that the nominee be alive on the date of the announcement.[18]

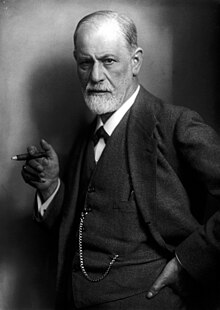

A maximum of three Nobel Laureates and two different works may be selected for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[19] True to its mandate, the Committee selects researchers working in the basic sciences over those who have made applied contributions. Harvey Cushing, a pioneering American neurosurgeon who identified Cushing's syndrome never was awarded the prize, nor was Sigmund Freud, as his psychoanalysis lacks hypotheses that could be tested experimentally.[6] The public expected Jonas Salk or Albert Sabin to win the prize for their development of the polio vaccines, but instead the award went to John Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins whose basic findings that the polio virus could reproduce in monkey cells in laboratory preparations was a fundamental step in the elimination of the disease of polio altogether.[20]

In the early days through the 1930s, there were frequent prize winners in classical Physiology, but after that the field began dissolving into specialities. The last classical physiology winners were John Eccles, Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley in 1963 for their findings regarding "unitary electrical events in the central and peripheral nervous system."[6]

Prizes

A Medicine or Physiology Nobel Prize laureate, earns a gold medal, a diploma bearing a citation, and a sum of money.[21] (Now the prize is commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Medicine.[10]) The amount of money awarded depends on the income of the Nobel Foundation that year.[22]

Medals

The Nobel Prize medals, minted by Myntverket[23] in Sweden are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. Each medal features an image of Alfred Nobel in left profile on the obverse (front side of the medal). The Nobel Prize medals for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, and Literature have identical obverses, showing the image of Alfred Nobel and the years of his birth and death (1833–1896). Before 1980, the medals were made of 23K gold; since then the medals are of 18K green gold, plated with 23K gold.[24]

The Physiology or Medicine medal awarded by the Karolinska Institute displays an image of "the Genius of Medicine holding an open book in her lap, collecting the water pouring out from a rock in order to quench a sick girl's thirst." The medal is inscribed with words taken from Virgil's Aeneid and reads: Inventas vitam juvat excoluisse per artes, which translates to "inventions enhance life which is beautified through art."[25]

Diplomas

Nobel laureates receive a Diploma directly from the hands of the King of Sweden. Each Diploma is uniquely designed by the prize-awarding institutions for the laureate that receives it, which in the case of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institute, and is created by well known artists and calligraphers from Sweden that have varied over time.[26] The Diploma contains a picture and text which states the name of the laureate and normally a citation of why they received the prize.[26]

Award Money

The laureate is also given a sum of money when they receive the Nobel Prize, in the form of a document confirming the amount awarded; in 2009 the monetary award was 10 million SEK (US$1.4 million).[22] The amount of prize money may differ depending on how much money the Nobel Foundation can award that year. If there are two winners in a particular category, the award grant is divided equally between the recipients. If there are three, the awarding committee has the option of dividing the grant equally, or awarding one-half to one recipient and one-quarter to each of the others.[22][27]

The Nobel Award Ceremony

The committee and institution serving as the selection board for the prize typically announce the names of the laureates in October. The prize is then awarded at formal ceremonies held annually on December 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death. "The highlight of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm is when each Nobel Laureate steps forward to receive the prize from the hands of His Majesty the King of Sweden. ... Under the eyes of a watching world, the Nobel Laureate receives three things: a diploma, a medal and a document confirming the prize amount".[19]

The Nobel Banquet is the banquet that is held every year in Stockholm City Hall in connection with the Nobel Prize.[19] It is a extravagant affair with the menu, planned months ahead of time, kept secret until the day of the event. The Nobel Foundation chooses the menu after tasting and testing selections submitted by selected chefs of international repute. Currently it is a three course dinner, although it was originally six courses when it began in 1901. Every Nobel Prize winner is allowed to bring up to 16 guests, and Sweden's royal family is always there. Typically the Prime Minister and other members of the government attend as well as representatives of the Nobel family.[28]

Laureates

The first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded in 1901 to the German physiologist Emil Adolf von Behring, "for his work on serum therapy, especially its application against diphtheria, by which he has opened a new road in the domain of biological science and thereby placed in the hands of the physician a victorious weapon against illness and deaths."[30] Behring's development of the diphtheria vaccine had lead to the eradication the disease in industrialized nations. In 1902, the award went to Ronald Ross for his work on malaria, "by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it".[31] He identified the mosquito as the transmitter of malaria, and worked tirelessly on measures to prevent malaria worldwide.[32][33] He is also the oldest prize winner, being 87 when he won.[34] The 1903 prize was awarded to Niels Ryberg Finsen, the first Danish winner, "in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation, whereby he has opened a new avenue for medical science". He died within a year after receiving the prize at the age of 43.[35][36]

Subsequently, laureates have won the Nobel Prize in a wide range of fields that relate to physiology or medicine. As of 2009, eight Prizes have been awarded for contributions in the field of signal transduction byG proteins and second messengers, 13 have been awarded for contributions in the field of neurobiology[37] and 13 have been awarded for contributions in Intermediary metabolism.[38] The 100 Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to 195 individuals, through 2009.[34][39] Ten women have won the prize: Gerty Cori (1947), Rosalyn Yalow (1977), Barbara McClintock (1983), Rita Levi-Montalcini (1986), Gertrude B. Elion (1988), Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard (1995), Linda B. Buck (2004), Françoise Barré-Sinoussi (2008), Elizabeth H. Blackburn (2009) and Carol W. Greider (2009).[40] Only one woman, Barbara McClintock, has won an unshared prize in this category for the discovery of genetic transposition.[34][41]

Because of the length of time that may pass before the significance of a discovery becomes apparent, some prizes are awarded many years after. Barbara McClintock made her discoveries in 1944, before the structure of the DNA molecule was known; she was not awarded the prize until 1983. Similarly, in 1916 Peyton Rous discovered the role tumor viruses in chickens, but was not warded the prize until 50 years later, in 1966.[10] Thus, longevity is an asset in winning the Nobel Prize,

There have been nine years in which the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was not awarded (1915–1918, 1921, 1925, 1940–1942). Most of these occurred during either World War I (1914–1918) or World War II (1939–1945).[39] In 1938 and 1939, Adolf Hitler's Third Reich forbade three laureates from Germany (Richard Kuhn, Adolf Friedrich Johann Butenandt, and Gerhard Domagk) from accepting their prizes.[10] Each man was later able to receive the diploma and medal but not the money.[39][42] Even though Sweden was officially neutral during World War II, the prizes were awarded irregularly. No prize was awarded in any category from 1940–42, due to the occupation of Norway by Germany. In the subsequent year, prizes were awarded for Physiology or Medicine as well as some other categories.[43]

Those selecting the recipients have exercised wide latitude in determining what falls under the umbrella of Physiology or Medicine. The awarding of the prize in 1973 to Nikolaas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch for their observations of animal behavioural patterns could be considered a prize in the behavioural sciences rather than medicine or physiology.[10] Tinbergen expressed surprise in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech at "the unconventional decision of the Nobel Foundation to award this year’s prize ‘for Physiology or Medicine’ to three men who had until recently been regarded as ‘mere animal watchers’".[44]

Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans and Oliver Smithies won the prize in 2007 for their work with embryonic stem cells.[45] The 2008 award went to Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, Elizabeth Blackburn and Luc Montagnier for discovering the Human immunodeficiency virus.[46] In 2009 the Nobel Prize was awarded to Elizabeth Blackburn, Carol W. Greider and Jack W. Szostak of the United States for discovering the process by which chromosomes are protected by telomeres (regions of repetitive DNA at the ends of chromosomes) and the enzyme telomerase; they shared the prize of 10,000,000 SEK (slightly more than €1 million, or US$1.4 million). This award in medicine was the first in the Nobel Prize's history that more than one woman has been the recipient of the Nobel Prize in a single year.[47]

There have been 37 times when the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to a single individual, 31 times when it was shared by two, and 32 times there were three winners (the maximum allowed). Rita Levi-Montalcini, an Italian neurologist, who together with colleague Stanley Cohen, received the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of Nerve growth factor (NGF), is the oldest living Nobel Laureate, as of June 2010.[39]

Controversies

Some of the awards have been controversial as demonstrated in the following examples. The 1923 award for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of insulin awarded only a year after the winning discovery,[48] has been heatedly debated. It was awarded to Frederick Banting and John James Richard Macleod for the discovery of insulin as a successful treatment of diabetes which infuriated Banting who regarded Macleod's involvement as minimal. Macleod was the department head at the University of Toronto but was not directly involved in the work. Banting thought his laboratory partner Charles Best, who had shared in the laboratory work of discovery, should have shared the prize with him as well. In fairness, he decided to give half of his prize money to Best. Maclead on his part felt the biochemist James Collip, who joined the laboratory team later, deserved to be included in the award and shared his prize money with him.[49][50]

In 1949, despite protests from the medical establishment, the Portuguese neurologist Antonio Egas Moniz received the Physiology or Medicine Prize for his development of the prefrontal leucotomy which he promoted by misrepresenting the results, declaring the procedure's success just 10 days postoperative. Due largely to the publicity surrounding the award, it was prescribed without regard for modern medical ethics. Favorable results were reported by such publications as The New York Times. It is estimated that around 5,000 lobotomies were performed between 1949 and 1952 in the United States, until the procedure's popularity faded. Joseph Kennedy, the father of John Kennedy subjected his daughter, Rosemary, to the procedure which incapacitated her to the degree that she needed to be institutionalized for the rest of her life.[6][51] [[:File:Rosalind Franklin.jpg|thumb|200px|Rosalind Franklin was never nominated for a Nobel Prize, despite her important work regarding the structure of DNA.[52]]]

The 1952 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded solely to Selman Waksman for his discovery of streptomycin had omitted the recognition some felt due his co-discoverer Albert Schatz.[53][54] There was a litigation brought by Schatz against Waksman over the details and credit of streptomycin discovery. The litigation result was such that Schatz was awarded a substantial settlement, and, together with Waksman, Schatz was be officially recognized as a co-discoverer of streptomycin as far as patent rights. However, he is not recognized as a Nobel Prize winner.[53]

Heinrich J. Matthaei broke the genetic code in 1961 with Marshall Warren Nirenberg in their poly-U experiment at NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, paving the way for modern genetics; but though Nirenberg became a much lauded Nobel Laureate in 1968, Matthaei, who was responsible for experimentally obtaining the first codon (genetic code) extract, and whose initial accurate results were tampered with by Nirenberg himself (due to the latter's belief in 'less precise', 'more believable' data presentation)[50] did not get any recognition or any Prize.

The 1962 Prize awarded to James D. Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins—for their work on DNA structure and properties—did not recognize contributing work from others, such as Alec Stokes, Herbert Wilson, and Erwin Chargaff. In addition, Erwin Chargaff, Oswald Avery and Rosalind Franklin (whose key DNA x-ray crystallography work was the most detailed yet least acknowledged among the three)[55] contributed directly to the ability of Watson and Crick to solve the structure of the DNA molecule—but Avery died in 1955, and Franklin in 1958 and posthumous nominations for the Nobel Prize are not permitted. However, recently unsealed files of the Nobel Prize nominations reveal that no one ever nominated Franklin for the prize when she was alive.[52] As a result of Watson's misrepresentations of Franklin and her role in the discovery of the double helix in his controversial book The Double Helix, Franklin has come to be portrayed as a classic victim of sexism in science.[56]

The 1975 Prize was awarded to David Baltimore, Renato Dulbecco and Howard Martin Temin "for describing how tumor viruses act on the genetic material of the cell". It has been argued that Dulbecco was distantly, if at all, involved in this groundbreaking work of discovery.[50] The award failed to recognize the contributions of Satoshi Mizutani, Temin's Japanese postdoctoral fellow.[57] Mizutani and Temin jointly discovered that the Rous sarcoma virus particle contained the enzyme reverse transcriptase. However, Mizutani was solely responsible for the original conception and design of the novel experiment confirming Temin's provirus hypothesis.[50]

The selection provision restriction the maximum number of nominees to three for any one prize have also caused controversy. From the 1950s onward, there has been an increasing trend to award the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to more than one person. There were 59 people who received the prize in the first 50 years of the last century, while 113 individuals received it between 1951 and 2000. This increase could be attributed to the rise of the international scientific community after World War II, resulting in more persons being responsible for the discovery, and nominated for, a particular prize. Also, current biomedical research is more often carried out by teams rather than by scientists working alone, making it unlikely that any one scientist is responsible for a discovery; this has meant that a prize nomination that would have to include more than three contributors is automatically excluded from consideration. Also, deserving contributors may not be nominated at all because the restriction results in a cut off point of three nominees per prize.[58]

See Also

References

- ^ Levinovitz, Agneta Wallin (2001). p. 5.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Levinovitz, Agneta Wallin (2001). p. 11.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Golden, Frederic (16 October 2000). "The Worst And The Brightest". Time Magazine. Time Warner. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Sohlman, Ragnar (1983). p. 13.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1904 Ivan Pavlov". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Feldman, Burton (2001). The Nobel prize: a history of genius, controversy, and prestige. Arcade Publishing. pp. 237-239, 286–289. ISBN 1559705922.

{{cite book}}: C1 control character in|pages=at position 4 (help) - ^ "History – Historic Figures: Alfred Nobel (1833–1896)". BBC. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ von Euler, U.S. (6 June 1981). "The Nobel Foundation and its Role for Modern Day Science" (PDF). Die Naturwissenschaften. Springer-Verlag. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "The Will of Alfred Nobel", nobelprize.org. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Levinovitz,, Agneta; Ringertz, Nils (2001). The Nobel Prize: the first 100 years. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 13, 23, 112–114.

{{cite book}}: Text "levinovitz2" ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Ragnar Sohlman – Executor of the Will". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "Nobel Prize History —". Infoplease.com. 1999-10-13. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Nobel Foundation (Scandinavian organisation) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AFP, "Alfred Nobel's last will and testament", The Local(5 October 2009): accessed 20 January 2010.

- ^ Foundation Books National Council of Science (2005). Nobel Prize Winners in Pictures. Foundation Books. p. viii. ISBN 8175962453.

{{cite book}}: Text "foundation" ignored (help) - ^ a b "Nomination and Selection of Medicine Laureates". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ "Nomination Facts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "What the Nobel Laureates Receive", accessed November 1, 2007.

- ^ Bishop, J. Michael (2004). How to Win the Nobel Prize: An Unexpected Life in Science. Harvard University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0674016254.

{{cite book}}: Text "bishop" ignored (help) - ^ Tom Rivers (2009-12-10). "2009 Nobel Laureates Receive Their Honors | Europe| English". .voanews.com. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Text "London 10 December 2009" ignored (help) - ^ a b c "The Nobel Prize Amounts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2010-01-15 Retrieved fro WebArchive 2010-06-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|accessdate= - ^ "Medalj – ett traditionellt hantverk" (in Swedish). Myntverket. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ "The Nobel Medals". Ceptualinstitute.com. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ "The Nobel Medal for Physiology or Medicine". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize Diplomas". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ Sample, Ian (2009-10-05). "Nobel prize for medicine shared by scientists for work on ageing and cancer". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ "Nobel Laureates dinner banquet tomorrow at Stokholm City Hall". DNA. December 9, 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1973". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ The Nobel Foundation (1901). "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1901 Emil von Behring". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1902 Ronald Ross". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "Sir Ronald Ross". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1902 Ronald Ross". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "Facts on the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1903 Niels Ryberg Finsen". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1903 Niels Ryberg Finsen". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ "Nobel Prizes in Nerve Signaling". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize Awarders". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ a b c d "Nobel Laureates Facts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2008-11-21. Cite error: The named reference "prizefacts" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Women Nobel Laureates". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1983 Barbara McClintock". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Wilhelm, Peter (1983). The Nobel Prize. Springwood Books. p. 85. ISBN 0862541115.

{{cite book}}: Text "Wilhelm" ignored (help) - ^ "All Nobel Laureates". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Tinbergen, Nikolaas (December 12, 1973). "Ethology and Stress Diseases" (PDF). nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2007 Mario R. Capecchi, Sir Martin J. Evans, Oliver Smithies". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2008 Harald zur Hausen, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, Luc Montagnier". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Harmon, Katherine (October 5, 2009). "Work on Telomeres Wins Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 3 U.S. Genetic Researchers [Update]". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Shalev, Baruch Aba (2002). 100 years of Nobel prizes. Americas Group. p. 73. ISBN 0935047379.

- ^ "The Discovery of Insulin". Nobelprize.org. February, 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Judson, Horace Freeland (2004). The Great Betrayal: Fraud in Science. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 59–61, 198, 291, 308. ISBN 0151008779.

{{cite book}}: Text "Judson" ignored (help) - ^ Day, Elizabeth (12 January 2008). "He was bad, so they put an ice pick in his brain..." The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ a b Fredholm, Lotta (30 September 2003). "The Discovery of the Molecular Structure of DNA – The Double Helix". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Streptomycin: arrogance and anger". by Steve Ainsworth pjonline.com

- ^ Wainwright, Milton "A Response to William Kingston, "Streptomycin, Schatz versus Waksman, and the balance of Credit for Discovery"", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences – Volume 60, Number 2, April 2005, pp. 218–220, Oxford University Press.

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine. "The Rosalind Franklin Papers". The DNA Riddle: King's College, London, 1951–1953. USA.gov. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Holt, Jim (October 28, 2002). "Photo Finish: Rosalind Franklin and the great DNA race". The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Weiss R.A., Viral RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus, Reviews in Medical Virology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 3–11(9), January/March 1998.

- ^ Lindsten, Jan (June 26, 2001). "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1901-2000". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Bishop, J. Michael (2004). How to Win the Nobel Prize: An Unexpected Life in Science. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674016254.

{{cite book}}: Text "bishop" ignored (help) - Doherty, Peter (2008). The Beginner's Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize: Advice for Young Scientists. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231138970.

{{cite book}}: Text "doherty" ignored (help) - Feldman, Burton (2001). The Nobel prize: a history of genius, controversy, and prestige. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1559705922.

- Foundation Books National Council of Science (2005). Nobel Prize Winners in Pictures. Foundation Books. p. viii. ISBN 8175962453.

{{cite book}}: Text "foundation" ignored (help) - Leroy, Francis (2003). A century of Nobel Prizes recipients: chemistry, physics, and medicine. CRC Press. ISBN 0824708768.

- Levinovitz, Agneta; Ringertz, Nils (2001). "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". The Nobel Prize: the first 100 years. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 981024665X.

{{cite book}}: Text "levinovitz" ignored (help) - Rifkind, David; Freeman, Geraldine L. (2005). The Nobel Prize winning discoveries in infectious diseases. Academic Press. ISBN 0123693535.

- Shalev, Baruch Aba (2002). 100 years of Nobel prizes. Americas Group. ISBN 0935047379.

- Wilhelm, Peter (1983). The Nobel Prize (First ed.). Springwood Books. ISBN 9780862541118.

External links

- All Nobel Laureates in Medicine – Index webpage on the official site of the Nobel Foundation.

- The Nobel Prize Medals and the Medal for the Prize in Economics – By Birgitta Lemmel; an article on the history of the design of the medals featured on the official site.

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine – Official site of the Nobel Foundation.

- Nobel Prize Internet Archive of Laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- The Nobel Banquets – A Century of Culinary History