Skanderbeg: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

* [[History of Albania]] |

* [[History of Albania]] |

||

* [[History of the Balkans]] |

* [[History of the Balkans]] |

||

* [[Myth of Skanderbeg]] |

|||

* [[Timeline of Skanderbeg]] |

* [[Timeline of Skanderbeg]] |

||

Revision as of 22:51, 15 April 2013

| George Kastrioti Skanderbeg | |

|---|---|

| Dominus Albaniae (lord of Albania) | |

| |

| Prince of Katsrioti | |

| Reign | 28 November 1443–17 January 1468 |

| Predecessor | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Successor | Gjon Kastrioti II |

| Chief of the League of Lezhë | |

| Reign | 2 March 1444–25 April ca. 1450 (or in 1468) |

| Predecessor | Post established |

| Successor | Lekë Dukagjini |

| Born | 6 May 1405[G] Principality of Kastrioti[A], modern day Albania |

| Died | 17 January 1468 (aged 62) Alessio (Lezhë), Republic of Venice, modern day Albania |

| Burial | Saint Nicholas Church of Lezhë, Albania |

| Spouse | Donika Arianiti |

| House | Kastrioti |

| Father | Gjon Kastrioti |

| Mother | Vojsava Tripalda |

| Religion | Christian →Islam (converted) →Christian (converted) |

| Signature | |

George Kastrioti Skanderbeg (6 May 1405 – 17 January 1468), widely known as Skanderbeg (from Template:Lang-tr, meaning "Lord Alexander", or "Leader Alexander"; Template:Lang-sq), was a 15th-century Albanian lord.[D] He was appointed as the governor of the Sanjak of Dibra by the Ottoman Turks in 1440. In 1444, he initiated and organized the League of Lezhë, which proclaimed him Chief of the League of the Albanian people, and defended the region of Albania against the Ottoman Empire for more than two decades.[1] Skanderbeg's military skills presented a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion, and he was considered by many in western Europe to be a model of Christian resistance against the Ottoman Muslims. Skanderbeg is Albania's most important national hero and a key figure of the Albanian National Awakening.

Skanderbeg was born in 1405[G] to the noble Kastrioti family, in a village in Dibra. Sultan Murad II took him hostage in 1423 and he fought for the Ottoman Empire during next twenty years. In 1443, he deserted the Ottomans during the Battle of Niš and became the ruler of Krujë. In 1444, he organized local leaders into the League of Lezhë, a federation aimed at uniting their forces for war against the Ottomans. Skanderbeg's first victory against the Ottomans, at the Battle of Torvioll in the same year marked the beginning of more than 20 years of war with the Ottomans. Skanderbeg's forces achieved more than 20 victories in the field and withstood three sieges of his capital, Krujë.

In 1451 he recognized de jure the suzerainty of Kingdom of Naples through the Treaty of Gaeta, to ensure a protective alliance, although he remained an independent ruler de facto.[2] In 1460–1461, he participated in Italy's civil wars in support of Ferdinand I of Naples. In 1463, he became the chief commander of the crusading forces of Pope Pius II, but the Pope died while the armies were still gathering. Left alone to fight the Ottomans, Skanderbeg did so until he died in January 1468.

Marin Barleti, an early 16th century Albanian historian, wrote a biography of Skanderbeg, which was printed between 1508 and 1510. The work, written in Latin and in a Renaissance and panegyric style, was translated into all the major languages of Western Europe from the 16th through the 18th centuries. Such translations inspired an opera by Vivaldi, and literary creations by eminent writers such as playwrights William Havard and George Lillo, French poet Ronsard, English poet Byron, and American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Name

George Kastrioti Skënderbeu appears in various Latin sources as Georgius Castriotus Scanderbegh. Gjergji is the Albanian equivalent of the name George. The form of his last name was given variously as Kastrioti,[3] Castriota,[4] Castriottis,[5] or Castriot.[6] The last name Kastrioti refers both to the Kastrioti family and to a municipality in northeastern Albania called Kastriot, in the modern Dibër District, from which the family's surname derives,[7][8][9] having its origin in the Latin castrum via the Greek word Κάστρο (Template:Lang-en).[10][11][12]

The Ottoman Turks gave him the name Iskender bey, meaning "Lord Alexander", or "Leader Alexander", which has been rendered as Scanderbeg or Skanderbeg in the English versions of his biographies, and Skënderbeu (or Skënderbej) is the Albanian version.[13] Latinized in Barleti's version as Scanderbegi and translated into English as Skanderbeg, the combined appellative is assumed to have been a comparison of Skanderbeg's military skill to that of Alexander the Great.[14]

Early life

George Kastrioti was born in 1405[G] in one of the two villages owned by his grandfather Pal Kastrioti.[A] Skanderbeg's father was Gjon Kastrioti, lord of Middle Albania, which included Mat, Mirditë and Dibër.[17] His mother was Voisava, originally from the Polog valley, north-western part of present-day Republic of Macedonia. There was a total of nine children, of whom George was the youngest son, his older brothers were Stanisha, Reposh and Kostandin, and his sisters were Mara, Jelena, Angjelina, Vlajka and Mamica.[3]

Gjon Kastrioti had been a vassal of the Sultan since the end of 14th century, and, as a consequence, paid tribute and provided military services to the Ottomans (like in the Battle of Ankara 1402[18]). In 1409 he sent his eldest son, Stanisha, to be the Sultan's hostage.[C] George seems to have gone to Sultan Murad II's court in 1423, when he was 18.[19] It is assumed that Skanderbeg remained Murad II's hostage for a maximum of three years.[19]

The earliest existing record of George's name is the First Act of Hilandar from 1426, when Gjon Kastrioti and his four sons donated the right to the proceeds from taxes collected from the two villages to the Monastery of Hilandar.[I][20] Afterwards, in the period between 1426 and 1431,[21] Gjon Kastrioti and his sons, with the exception of Stanisha, purchased four adelphates (rights to reside on monastic territory and receive subsidies from monastic resources) to the Saint George tower and to some property within the monastery as stated in the Second Act of Hilandar.[20][22]

Skanderbeg participated in Ottoman campaigns and because of his military actions against the Christians his father Gjon had to seek forgiveness from the Venetian Senate in 1428.[23] In 1430, Gjon Kastrioti was defeated in a battle by the Ottoman governor of Skopje, Isa bey Evrenos and as a result, his territorial possessions were extremely reduced.[24] Later that year, Skanderbeg started fighting for Murad II in his expeditions, and gained the title of sipahi.[25] Although Skanderbeg was summoned home by his relatives when George Arianiti and Andrew Thopia along with other chiefs from the region between Vlorë and Shkodër organized a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in the period of 1432—1436, he did nothing, remaining loyal to the sultan.[26] In 1437–1438,[27] he became a governor (Template:Lang-tr) of the Krujë subaşilik[22] before Hizir Bey was again appointed to that position in November 1438.[28] Until May 1438, Skanderbeg controlled a relatively large timar (of the vilayet of Dhimitër Jonima) composed of nine villages which previously belonged to his father Gjon (this timar was listed in Ottoman registers as Gjon's land, Template:Lang-tr).[22][29]

It was because of Skanderbeg's display of military merit in several Ottoman campaigns, that Murad II (r. 1421–1451) had given him the title of vali. At that time, Skanderbeg was leading a cavalry unit of 5,000 men.[30]

After his brother Reposh's death on 25 July 1431[31] and the later deaths of Kostandin and Skanderbeg's father (who died in 1437), Skanderbeg and his surviving brother Stanisha maintained the relations that their father had with the Republic of Ragusa and the Republic of Venice. In 1438 and 1439, they managed to have the same privileges that their father had with those states.[27] During the 1438–1443 period, he is thought to have been fighting alongside the Ottomans in their European campaigns, mostly against the Christian forces led by Janos Hunyadi.[27] In 1440 Skanderbeg was appointed as sanjakbey of Sanjak of Dibra.[32][33] During his stay in Albania as Ottoman governor, he maintained close relations with the population in his father's former properties and also with other Albanian noble families.[22]

Albanian resistance

Rise

In early November 1443, Skanderbeg saw his opportunity to rebel against Sultan Murad II during the Battle of Niš, while fighting against the crusaders of John Hunyadi.[34] Skanderbeg quit the field along with 300 other Albanians serving in the Ottoman army.[34] He immediately went to Krujë on November 28,[35] and by forging a letter from Murad II to the Governor of Krujë, he became lord of the city.[34][36] To reinforce his intention of gaining control of the former domains of Zeta, Skanderbeg proclaimed himself the heir of the Balsha family. After various attacks against Bar and Ulcinj along with Đurađ Branković, Stefan Crnojević[37] and Albanians of the area, the Venetians offered rewards for his assassination.[2] After capturing some other minor surrounding castles and eventually gaining control over more than his father Gjon Kastrioti's domains[clarification needed], Skanderbeg abjured Islam and proclaimed himself the avenger of his family and country.[38] He raised a red flag with the double-headed eagle silhouette on it: Albania uses a similar flag and symbol to this day.[39]

On March 2, 1444, Skanderbeg managed to bring together all the Albanian princes in the city of Lezhë and form the League of Lezhë.[40] Particularly strong was his alliance with Gjergj Arianiti, a member of the Arianiti family, whose daughter Donika he later married.[41][42][43] Gibbon reports that the "Albanians, a martial race, were unanimous to live and die with their hereditary prince", and that "in the assembly of the states of Epirus, Skanderbeg was elected general of the Turkish war and each of the allies engaged to furnish his respective proportion of men and money".[44] With this support, Skanderbeg built fortresses (Rodoni Castle) and organized a mobile defense army that forced the Ottomans to disperse their troops, leaving them vulnerable to the hit-and-run tactics of the Albanians.[45] Skanderbeg fought a guerrilla war against the opposing armies by using the mountainous terrain to his advantage. During the first 8–10 years, Skanderbeg commanded an army of generally 10,000-15,000 soldiers,[46] but only had absolute control over the men from his own dominions, and had to convince the other princes to follow his policies and tactics.[41]

In the summer of 1444, in the Plain of Torvioll, the united Albanian armies under Skanderbeg faced the Ottomans who were under direct command of the Turkish general Ali Pasha, with an army of 25,000 men.[47] Skanderbeg had under his command 7,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. 3,000 cavalry were hidden behind enemy lines in a nearby forest under the command of Hamza Kastrioti. At a given signal they descended, encircled the Ottomans and gave Skanderbeg a much needed victory. About 8,000 Ottomans were killed and 2,000 were captured.[41] Skanderbeg's first victory echoed across Europe because this was one of the few times that an Ottoman army was defeated in a pitched battle on European soil. In the following two years, Skanderbeg defeated the Ottomans two more times, on October 10, 1445, when Ottoman forces from Ohrid suffered severe losses,[48] and again in the Battle of Otonetë on September 27, 1446.[49][50]

At the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, the Republic of Venice was supportive of Skanderbeg, considering his forces to be a buffer between them and the Ottoman Empire. Lezhë, where the eponymous league was established, was Venetian territory, and the assembly met with the approval of Venice. The later affirmation of Skanderbeg and his rise as a strong force on their borders, however, was seen as a menace to the interests of the Republic, leading to a worsening of relations and the dispute over the fortress of Dagnum which triggered the Albanian-Venetian War of 1447–1448. The Venetians sought by every means to overthrow Skanderbeg or bring about his death, even offering a life pension of 100 golden ducats annually for the person who would kill him.[50][51] During the conflict, Venice invited the Ottomans to attack Skanderbeg simultaneously from the east, facing the Albanians with a two-front conflict.[52]

On May 14, 1448, an Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad II and his son Mehmed laid siege to the castle of Svetigrad. The Albanian garrison in the castle resisted the frontal assaults of the Ottoman army, while Skanderbeg harassed the besieging forces with the remaining Albanian army under his personal command. On July 23, 1448, Skanderbeg won a battle near Shkodër against a Venetian army led by Andrea Venier. In late summer 1448, due to a lack of potable water,[B] the Albanian garrison eventually surrendered the castle with the condition of safe passage through the Ottoman besieging forces, a condition which was accepted and respected by Sultan Murad II.[53] Although his loss of men was minimal, Skanderbeg lost the castle of Svetigrad, which was an important stronghold that controlled the fields of Macedonia to the east.[53] At the same time, he besieged the towns of Durazzo (modern Durrës) and Lezhë which were then under Venetian rule.[54] In August 1448, Skanderbeg won a battle against Mustafa Pasha in Dibër. This forced the Venetians to offer a peace treaty to Skanderbeg.

The peace treaty, signed between Skanderbeg and Venice on 4 October 1448, envisioned that Venice would keep Dagnum and its environs, but would cede to Skanderbeg the territory of Buzëgjarpri at the mouth of the river Drin, and also that Skanderbeg would enjoy the privilege of buying, tax-free, 200 horse-loads of salt annually from Durazzo. In addition Venice would pay Skanderbeg 1,400 ducats. During the period of clashes with Venice, Skanderbeg intensified relations with Alfonso V of Aragon (r. 1416–1458), who was the main rival of Venice in the Adriatic, where his dreams for an empire were always opposed by the Venetians.[55]

The Albanian army under Skanderbeg did not participate in this battle as he was prevented from linking with the Hunyadi's army by the Ottomans and their allies.[56] It is believed that he was delayed by Đurađ Branković, then allied with Sultan Murad II, although Brankovic's exact role is disputed.[57][58][59] As a result Skanderbeg ravaged his domains as a punishment for the desertion of Christian cause.[56][60] He appears to have marched to join Hunyadi immediately after making peace with the Venetians, and to have been only 20 miles from Kosovo Polje when the Hungarian army finally broke.[61]

In 1448, Alfonso V suffered a rebellion caused by certain barons in the rural areas of his Kingdom of Naples. He needed reliable troops to deal with the uprising, so he called upon Skanderbeg for assistance. Skanderbeg responded to Alfonso's request for aid by sending to Italy a detachment of Albanian troops commanded by General Demetrios Reres. These Albanians were successful in quickly suppressing the rebellion. Many of these troops settled there.[62] King Alfonso rewarded Demetrios Reres for his service to Naples by appointing him governor of Calabria. One year later, in 1449, another detachment of Albanian troops was sent to garrison Sicily against a rebellion and invasion. This time the troops were led by Giorgio Reres and Basilio Reres, the sons of Demetrios.[63]

In June 1450, two years after the Ottomans had captured Svetigrad, they laid siege to Krujë with an army numbering approximately 100,000 men and led again by Sultan Murad II himself and his son, Mehmed.[64] Following a scorched earth strategy (thus denying the Ottomans the use of necessary local resources), Skanderbeg left a protective garrison of 1,500 men under one of his most trusted lieutenants, Vrana Konti, while, with the remainder of the army, which included many Slavs, Germans, Frenchmen and Italians,[65][66] he harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë by continuously attacking Sultan Murad II's supply caravans. The garrison repelled three major direct assaults on the city walls by the Ottomans, causing great losses to the besieging forces. Ottoman attempts at finding and cutting the water sources failed, as did a sapped tunnel, which collapsed suddenly. An offer of 300,000 aspra (Turkish silver coins) and a promise of a high rank as an officer in the Ottoman army made to Vrana Konti, were both rejected by him.[67]

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetian merchants from Shkodër sold food to the Ottoman army and those of Durazzo supplied Skanderbeg's army.[68] An angry attack by Skanderbeg on the Venetian caravans raised tension between him and the Republic, but the case was resolved with the help of the bailo of Durazzo who stopped any Venetian merchants from furnishing any longer the Ottomans.[67] Venetians' help to the Ottomans notwithstanding, by September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in disarray, as the castle was still not taken, the morale had sunk, and disease was running rampant. Murad II acknowledged that he could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms, and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to Edirne, leaving behind several thousand dead soldiers.[67] A few months later, on February 3, 1451, Murad died in Edirne and was succeeded by his son Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481).[69]

Consolidation

Although Skanderbeg had achieved success at resisting Murad II himself, harvests were unproductive and famine was widespread. Following Skanderbeg's requests, King Alfonso V helped him in this situation and the two parties signed the Treaty of Gaeta on March 26, 1451, according to which, Skanderbeg would be formally a vassal of Alfonso in exchange for military aid.[70] More explicitly, Skanderbeg recognized King Alfonso's sovereignty over his lands in exchange for the help that King Alfonso would give to him in the war against the Ottomans.[E] King Alfonso pledged to respect the old privileges of Krujë and Albanian territories and to pay Skanderbeg an annual 1,500 ducats, while Skanderbeg pledged to make his fealty to King Alfonso only after the full expulsion of the Ottomans from the country[clarification needed], a condition never reached in Skanderbeg's lifetime.[55]

A month after the treaty, on 21 April 1451 in an Eastern Orthodox Ardenica Monastery,[71][72] Skanderbeg married Donika Kastrioti, daughter of Gjergj Arianiti, one of the most influential Albanian noblemen, strengthening the ties between them.[42] Their only child was Gjon Kastrioti II.

Right after the Treaty of Gaeta, Alfonso V signed other treaties with the rest of the most important Albanian noblemen, including Golem Arianit Komneni,[73] and with the Despot of the Morea, Demetrios Palaiologos.[74] These movements of Alfonso show that he was thinking about a crusade starting from Albania and Morea, which actually never took place.[75] Following the Treaty of Gaeta, in the end of May 1451, a small detachment of 100 Catalan soldiers, headed by Bernard Vaquer, was established at the castle of Krujë. One year later, in May 1452, another Catalan nobleman, Ramon d’Ortafà, came to Krujë with the title of viceroy.[E] In 1453, Skanderbeg paid a secret visit to Naples and the Vatican, probably to discuss the new conditions after the fall of Constantinople and the planning of a new crusade which Alfonso would have presented to Pope Nicholas V in a meeting of 1453—1454.[76]

During the five years which followed the First Siege of Krujë, Albania was allowed some respite as the new sultan set out to conquer the last vestiges of the Byzantine Empire, but a battle did take place in 1452 when another Ottoman army sent to Albania was defeated again by Skanderbeg's forces. During this period, skirmishes between Skanderbeg and the Dukagjin family, which had been dragging on for years, were put to an end by a reconciliatory intervention of the Pope, and in 1454, a peace treaty between them was finally reached.[77]

In November 1453, Skanderbeg informed King Alfonso that he had conquered some territories and a castle, and Alfonso replied some days later that soon Ramon d’Ortafà would return to continue the war against the Ottomans and promised more troops and supplies. In the beginning of 1454, Skanderbeg and the Venetians[78] informed King Alfonso and the Pope about a possible Ottoman invasion and asked for help. The Pope sent 3,000 ducats while Alfonso sent 500 infantry and a certain amount of money,[79] along with a message directed to Skanderbeg.[80] Meanwhile, the Venetian Senate was resenting Skanderbeg's alliance with the Kingdom of Naples, an old enemy of the Republic. Frequently they delayed their tributes to Skanderbeg and this was long a matter of dispute between the parties, with Skanderbeg threatening war on Venice at least three times during the 1448–1458 period, and Venice conceding in a conciliatory tone.[81]

In June 1454, Ramon d’Ortafà returned to Krujë, this time with the title of viceroy of Albania, Greece, and Slavonia, with a personal letter to Skanderbeg as the Captain-General of the armed forces in Albania.[82] Along with Ramon d’Ortafà, King Alfonso V also sent the clerics Fra Lorenzo da Palerino and Fra Giovanni dell’Aquila to Albania with a tabby flag[clarification needed] embroidered with a white cross as a symbol of the Crusade which was about to begin.[83][84] Even though this crusade never materialized, the Neapolitan troops were used in the Siege of Berat where they were almost entirely annihilated and were never replaced.

The Siege of Berat was the first real test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg. That siege would end up in a defeat for the League of Lezhë forces.[85] Skanderbeg besieged the town's castle for months, causing the demoralized Turkish officer in charge of the castle to promise his surrender.[85] At that point, Skanderbeg relaxed his grip, split his forces, and departed the siege, leaving behind one of his generals, Muzakë Topia, and half of his cavalry on the banks of the Osum River in order to finalize the surrender.[85] It was a costly error—the Ottomans saw this moment as an opportunity for attack and sent a large cavalry force from Anatolia[need quotation to verify], led by Isak-Beg, to reinforce the garrison.[85] The Albanian forces had become overconfident and lulled into a false sense of security.[85] The Ottomans caught the Albanian cavalry by surprise while they were resting on the banks of the Osum River, and almost all the 5,000 Albanian cavalry laying siege to Berat were killed.[85] Most of the forces belonged to Gjergj Arianiti, whose role as the greatest supporter of Skanderbeg diminished after siege of Berat ended up in defeat.[85]

The defeat of Berat somewhat affected the attitude of other Albanian noblemen. One of them, Moisi Arianit Golemi, defected to the Turks and returned to Albania in 1456 as a commander of a Turkish army of 15,000 men, but he was defeated by Skanderbeg in Battle of Oranik.[86] Later that year, he returned to Albania asking for Skanderbeg's pardon, and once pardoned, remained loyal until his death in 1464.[86]

In 1456, one of Skanderbeg's nephews (the son of his sister Jelena), Gjergj Stress Balsha, sold the fortress of Modrič (today in Macedonia) to the Ottomans for 30,000 silver ducats. He tried to cover up the act; however, his treason was discovered and he was sent to prison in Naples.[87]

In the beginning of 1457, another nobleman, Hamza Kastrioti, Skanderbeg's own nephew and his closest collaborator, defected to the Turks when he lost his hope of succession after the birth of Skanderbeg's son Gjon Kastriot II. In the summer of 1457, an Ottoman army numbering approximately 70,000 men[88] invaded Albania with the hope of destroying Albanian resistance once and for all. This army was led by Isak-Beg and by Hamza Kastrioti, the commander who knew all about Albanian tactics and strategy. After wreaking much damage to the countryside,[88] the Ottoman army set up camp at the Ujebardha field (literally translated as "White Water"), halfway between Lezhë and Krujë. After having avoided the enemy for months, calmly giving to the Turks and his European neighbours the impression that he was defeated, on 2 September Skanderbeg attacked the Ottomans in their encampments and defeated them.[89] This was one of the most famous victories of Skanderbeg over the Ottomans, which led to a five-year peace treaty with Sultan Mehmed II. Hamza was captured[90] and sent to detention in Naples.[91]

After the victorious Battle of Ujëbardha, Skanderbeg's relations with the Papacy under Pope Calixtus III were intensified. The reason was that during this time, Skanderbeg's military undertakings involved considerable expense which the contribution of Alfonso V of Aragon was not sufficient to defray.[92] In 1457, Skanderbeg requested help from Calixtus III. Being himself in financial difficulties, the Pope could do no more than send Skanderbeg a single galley and a modest sum of money, promising more ships and larger amounts of money in the future.[92] On December 23, 1457, Calixtus III appointed Skanderbeg as Captain-General of the Curia in the war against the Turks and declared him Captain-General of the Holy See. The Pope also gave him the title Athleta Christi, or Champion of Christ.[92] Meanwhile, Ragusa bluntly refused to release the funds which had been collected in Dalmatia for the crusade and which, according to the Pope, were to have been distributed in equal parts to Hungary, Bosnia, and Albania. The Ragusans even entered into negotiations with Mehmed.[92] At the end of December 1457, Calixtus threatened Venice with an interdict and repeated the threat in February 1458. As the captain of the Curia, Skanderbeg appointed the duke of Leukas (Santa Maura), Leonardo III Tocco, formerly the prince of Arta and "despot of the Rhomaeans", a figure virtually unknown except in Southern Epirus, as a lieutenant in his native land.[92]

On June 27, 1458, King Alfonso V died at Naples and Skanderbeg sent emissaries to his son and successor, King Ferdinand.[93] According to the historian C. Marinesco, the death of King Alfonso marked the end of the Aragonese dream of a Mediterranean Empire and also the hope for a new crusade in which Skanderbeg was assigned a leading role.[94] The relationship of Skanderbeg with the Kingdom of Naples continued even after Alfonso V's death, but the situation had changed; Ferdinand I was not as able as his father and now it was Skanderbeg's turn to help King Ferdinand to regain and maintain his kingdom. In 1459 Skanderbeg captured fortress of Sati from Ottoman Empire and ceded it to Venice in order to secure cordial relationship with Signoria.[95] The reconciliation reached the point where Pope Pius II suggested entrusting Skanderbeg's dominions to Venice during his Italian expedition.

In 1460, King Ferdinand had serious problems with another uprising of the Angevins and asked for help from Skanderbeg. This invitation worried King Ferdinand's opponents, and Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta declared that if Ferdinand of Naples received Skanderbeg, Malatesta would go to the Turks.[96] In the month of September 1460, Skanderbeg dispatched a company of 500 cavalry under his nephew, Gjok Stres Balsha.[97] Ferdinand's main rival, Giovanni Antonio Orsini, Prince of Taranto, in correspondence with Skanderbeg tried to dissuade the Albanian from this enterprise and even offered him an alliance.[97] This did not affect Skanderbeg, who answered on October 31, 1460, that he owed fealty to the Aragon family, especially in times of hardship.[F] When the situation became critical, Skanderbeg made a three-year armistice with the Ottomans on April 17, 1461, and in late August 1461, landed in Puglia with an expeditionary force of 1,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry. At Barletta and Trani, he managed to defeat the Italian and Angevin forces of Giovanni Antonio Orsini, Prince of Taranto, secured King Ferdinand's throne, and returned to Albania.[98][99] King Ferdinand was grateful to Skanderbeg for this intervention for the rest of his life: at Skanderbeg's death, he rewarded his descendants with the castle of Trani, and the properties of Monte Sant'Angelo and San Giovanni Rotondo.[99]

Last years

After securing the Neapolitan kingdom, a crucial ally in his struggle, Skanderbeg returned home after being informed of Ottoman movements. There were three Ottoman armies approaching: the first, under the command of Sinan Pasha, was defeated at Mokra (in Makedonski Brod); the second, under the command of Hussain Bey, was defeated in the Battle of Ohër, where the Turkish commander was captured; and the third was defeated in the region of Skopje.[100] This forced Sultan Mehmed II to agree to a 10-year armistice which was signed in April 1463 in Skopje.[100] Skanderbeg did not want peace, but he was outvoted in the League of Lezhë, and Tanush Thopia's willingness for peace prevailed. Tanush himself went to Tivoli to explain to the Pope why the League had opted for peace with Mehmed II. He pointed out that Skanderbeg would be ready to go back to war should the Pope ask for it.[100]

Meanwhile, the position of Venice toward Skanderbeg had changed perceptibly because the Republic had entered in their first war with the Turks (1463–1479). During this period the Republic saw Skanderbeg as an invaluable ally, and on 20 August 1463, the peace treaty of 1448 was renewed and this time other conditions were added: the right of asylum in Venice, an article stipulating that any Venetian treaty with the Turks would include a guarantee of Albanian independence, and allowing the presence of several Venetian ships in the Adriatic waters around Lezhë.[101]

In November 1463, Pope Pius II tried to organize a new crusade against the Ottoman Turks, similar to what Pope Nicholas V and Pope Calixtus III had tried to do before him. Pius II invited all the Christian nobility to join, and the Venetians immediately answered the appeal.[102] So did Skanderbeg, who on 27 November 1463, declared war on the Ottomans and attacked the Turkish forces near Ohrid. Pius II's planned crusade envisioned assembling 20,000 soldiers in Taranto, while another 20,000 would be gathered by Skanderbeg. They would have been summoned in Durazzo under Skanderbeg's leadership and would have formed the central front against the Ottomans. However, Pius II died in August 1464, at the crucial moment when the crusading armies were gathering and preparing to march in Ancona, and Skanderbeg was again left alone facing the Ottomans.[102]

In April 1465, at the Battle of Vaikal, Skanderbeg fought and defeated Ballaban Badera, an Albanian Ottoman sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Ohrid.[103] However, during an ambush in the same battle, Ballaban managed to capture some important Albanian noblemen, including Moisi Arianit Golemi, a cavalry commander, Vladan Gjurica, the chief army quartermaster, Muzaka of Angelina, a nephew of Skanderbeg, and 18 other officers.[102] These men were sent immediately to Constantinople (Istanbul) where they were skinned alive for fifteen days and later cut to pieces and thrown to the dogs.[102] Skanderbeg's pleas to have these men back, by either ransom or prisoner exchange, failed.[102]

Later that same year, two other Ottoman armies appeared on the borders. The commander of one of the Ottoman armies was Ballaban Pasha, who, together with Jakup Bey, the commander of the second army, planned a double-flank envelopment. Skanderbeg, however, attacked Ballaban's forces at the Second Battle of Vajkal, where the Turks were defeated. This time, all the Turkish prisoners were slain in an act of revenge for the previous execution of Albanian captains.[104] The other Turkish army, under the command of Jakup Bey, was also defeated some days later in Kashari field near Tirana.[104]

In 1466, Sultan Mehmed II personally led an army of 30,000 into Albania and laid the Second Siege of Krujë, as his father had attempted 16 years earlier.[105] The town was defended by a garrison of 4,400 men, led by Prince Tanush Thopia.[105] After several months of siege, destruction and killings all over the country, Mehmed II, like his father, saw that seizing Krujë was impossible for him to accomplish by force of arms. Subsequently, he left the siege to return to Istanbul.[105] However, he left the force of 30,000 men under Ballaban Pasha to maintain the siege by building a castle in central Albania, which he named Il-basan (modern Elbasan), in order to support the siege. Durazzo would be the next target of the sultan in order to be used as a strong base opposite the Italian coast.[105]

Skanderbeg spent the following winter of 1466—1467 in Italy, of which several weeks were spent in Rome trying to persuade Pope Paul II to give him money. At one point, he was unable to pay for his hotel bill, and he commented bitterly that he should be fighting against the Church rather than the Turks.[106] Only when Skanderbeg left for Naples did Pope Paul II give him 2,300 ducats. The court of Naples, whose policy in the Balkans hinged on Skanderbeg's resistance, was more generous with money, armaments and supplies. However, it is probably better to say that Skanderbeg financed and equipped his troops largely from local resources, richly supplemented by Turkish booty.[107] It is safe to say that the papacy was generous with praise and encouragement, but its financial subsidies were limited. It is possible that the Curia only provided to Skanderbeg 20,000 ducats in all, which could have paid the wages of 20 men over the whole period of conflict.[107]

However, on his return he allied with Lekë Dukagjini, and together on April 19, 1467, they first attacked and defeated, in the Krrabë region, the Turkish reinforcements commanded by Yonuz, Ballaban's brother. Yonuz himself and his son, Haydar were taken prisoner.[104] Four days later, on April 23, 1467, they attacked the Ottoman forces laying siege to Krujë. The Second Siege of Krujë was eventually broken, resulting in the death of Ballaban Pasha by an Albanian arquebusier[41][100] named Gjergj Aleksi.[108] After these events, Skanderbeg's forces besieged Elbasan but failed to capture it because of the lack of artillery and sufficient number of soldiers.[109]

The destruction of Ballaban Pasha's army and the siege of Elbasan forced Mehmed II to march against Skanderbeg again in the summer of 1467. Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains while Ottoman grand vizier Mahmud Pasha Angelović pursued him but failed to find him because Skanderbeg succeeded in fleeing to the coast.[110] Mehmed II energetically pursued the attacks against the Albanian strongholds while sending detachments to raid the Venetian possessions (especially Durazzo) and to keep them isolated. The Ottomans failed again, in their third Siege of Krujë, to take the city and subjugate the country, but the degree of destruction was immense.[111]

During the Ottoman incursions, the Albanians suffered a great number of casualties, especially to the civilian population, while the economy of the country was in ruins. The above problems, the loss of many Albanian noblemen, and the new alliance with Lekë Dukagjini, caused Skanderbeg to call together in January 1468 all the remaining Albanian noblemen to a conference in the Venetian stronghold of Lezhë to discuss the new war strategy and to restructure what remained from the League of Lezhë.[109] During that period, Skanderbeg fell ill with malaria and died on January 17, 1468.[109] He was 62.

Aftermath

After Skanderbeg's death, Venice asked and obtained from his widow the permission to defend Krujë and the other fortresses with Venetian garrisons.[109] Krujë held out during its fourth siege, started in 1477 by Gedik Ahmed Pasha, until 16 June 1478, when the city was starved to death and finally surrendered to Sultan Mehmed II himself.[109] Demoralized and severely weakened by hunger and lack of supplies from the year-long siege, the defenders surrendered to Mehmed, who had promised them to leave unharmed in exchange.[112] As the Albanians were walking away with their families however, the Ottomans reneged on this promise, killing the men and enslaving the women and children.[112] In 1479, an Ottoman army, headed again by Mehmed II, besieged and captured Shkodër,[109] reducing Venice's Albanian possessions only to Durazzo, Antivari, and Dulcigno.[109]

Meanwhile, King Ferdinand of Naples' gratitude toward Skanderbeg for the help given during this Italian campaign continued even after Skanderbeg's death. In a letter dated to 24 February 1468, King Ferdinand expressively stated that "Skanderbeg was like a father to us" and "We regret this (Skanderbeg's) death not less than the death of King Alfonso", offering protection for Skanderbeg's widow and his son. It is relevant to the fact that the majority of Albanian leaders after the death of Skanderbeg found refuge in the Kingdom of Naples and this was also the case for the common people trying to escape from the Ottomans, who formed Arbëresh colonies in that area.

On April 25, 1479, the Ottoman forces captured the Venetian-controlled Shkodër, which had been besieged since May 14, 1478.[113] Shkodër was the last Albanian castle to fall to the Ottomans. The Albanian resistance to the Ottoman invasion continued after Skanderbeg's death by his son, Gjon Kastrioti II, who tried to liberate Albanian territories from Ottoman rule in 1481–1484.[114] In addition, a major revolt in 1492 occurred in southern Albania, mainly in the Labëria region, and Bayazid II was personally involved with crushing the resistance.[115] In 1501, Gjergj Kastrioti II, grandson of Skanderbeg and son of Gjon Kastrioti II, along with Progon Dukagjini and around 150–200 stratioti, went to Lezhë and organized a local uprising, but that too was unsuccessful.[116] The Venetians evacuated Durazzo in 1501.

Descendants

Skanderbeg’s family, the Kastrioti Scanderbeg, were invested with a Neapolitan dukedom after their flight from the Ottoman conquest of Albania.[117] They obtained a feudal domain, the Duchy of San Pietro in Galatina and the County of Soleto (Province of Lecce, Italy).[118] Gjon Kastrioti II, Scanderbeg’s son, married Irene Brankovic Palaiologina, daughter of Lazar Branković, despot of Serbia and one of the last descendents of the Byzantine imperial family, the Palaiologos.[118]

Two lines of the Castriota Scanderbeg family lived from that time onwards to the present day in southern Italy, one of which has descended from Pardo Castriota Scanderbeg and the other from Achille Castriota Scanderbeg, who were both biological sons of Duke Ferrante, son of Gjon and Scanderbeg’s grandson. They are part of the Italian nobility and members of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta with the highest rank of nobility.[119]

The only legitimate daughter of Duke Ferrante, Irene Castriota Scanderbeg, born to Andreana Acquaviva d'Aragona from the Nardò dukes, inherited the paternal estate, bringing the Duchy of Galatina and County of Soleto into the Sanseverino family after her marriage with Prince Pietrantonio Sanseverino (1508–1559). They had a son, Nicolò Bernardino Sanseverino (1541–1606), but the The only legitimate daughter of Duke Ferrante, Irene Castriota Scanderbeg, born to Andreana Acquaviva d'Aragona from the Nardò dukes, inherited the paternal estate, bringing the Duchy of Galatina and County of Soleto into the Sanseverino family after her marriage with Prince Pietrantonio Sanseverino (1508–1559). They had a son, Nicolò Bernardino Sanseverino (1541–1606), but the male line of descendants was lost after Irenece Castriota. Through the famale lines his descendants include the ruling (or former ruling) families of Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria-Hungary, Prussia, Serbia, and some members of the British royal family. Other prominent modern descendants include Filippo Castriota, collaborator of Ismail Qemali, founder of modern Albania and author Giorgio Maria Castriota.

Legacy

The Ottoman Empire's expansion ground to a halt during the time that Skanderbeg's forces resisted. He has been credited with being one of the main reasons for delaying Ottoman expansion into Western Europe, giving the Italian principalities more time to better prepare for the Ottoman arrival.[41][120] While the Albanian resistance certainly played a vital role, it was one of numerous relevant events that played out in the mid-15th century. Much credit must also go to the successful resistance mounted by Vlad III Dracula in Wallachia and Stephen III the Great of Moldavia, who dealt the Ottomans their worst defeat at Vaslui, among many others, as well as the defeats inflicted upon the Ottomans by Hunyadi and his Hungarian forces.[121] Along with Skanderbeg, Stephen III the Great and Hunyadi achieved the title of Athletae Christi (Christ's champions). The distinguishing characteristic of Skanderbeg was the maintenance of such an effective resistance for a long period of time (25 years) against one of the 15th century's strongest powers while possessing very limited economic and human resources. His political, diplomatic, and military abilities were the main factors enabling the small Albanian principalities to achieve such a success.

Skanderbeg is considered today a commanding figure not only in the national consciousness of Albanians but also of 15th-century European history.[122] According to archival documents, there is no doubt that Skanderbeg had already achieved a reputation as a hero in his own time.[123] The failure of most European nations, with the exception of Naples, to give him support, along with the failure of Pope Pius II's plans to organize a promised crusade against the Turks meant that none of Skanderbeg's victories permanently hindered the Ottomans from invading the Western Balkans.[123] When in 1481 Sultan Mehmet II captured Otranto, he massacred the male population, thus proving what Skanderbeg had been warning about.[123] Skanderbeg's main legacy was the inspiration he gave to all of those who saw in him a symbol of the struggle of Christendom against the Ottoman Empire.[124] During the Albanian National Awakening Skanderbeg was a symbol of national cohesion and cultural affinity with Europe.[125]

Skanderbeg's struggle against the Ottomans became highly significant to the Albanian people. It strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their identity, and was a source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.[126]

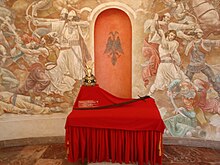

Probably one of the most important legacies of Skanderbeg lies with his military mastery. The trouble that he caused to the Ottoman Empire military forces was such that when the Ottomans found the grave of Skanderbeg in Saint Nicholas, a church in Lezhë, they opened it and made amulets of his bones, believing that these would confer bravery on the wearer.[127] Indeed the damage inflicted to the Ottoman Army was such that Skanderbeg is said to have slain three thousand Turks with his own hand during his campaigns. Among stories told about him was that he never slept more than five hours at night and could cut two men asunder with a single stroke of his scimitar, cut through iron helmets, kill a wild boar with a single stroke, and cleave the head off a buffalo with another.[128] James Wolfe, commander of the British forces at Quebec, spoke of Skanderbeg as a commander who "excels all the officers, ancient and modern, in the conduct of a small defensive army".[129] On October 27, 2005, the United States Congress issued a resolution "honoring the 600th anniversary of the birth of Gjergj Kastrioti (Scanderbeg), statesman, diplomat, and military genius, for his role in saving Western Europe from Ottoman occupation."[130] Fully understanding the importance of the hero to the Albanians, Nazi Germany formed in February 1944, the 21st SS Division Skanderbeg, with 6,491 Kosovo Albanians.[131]

Skanderbeg is also remembered as a statesman. During his reign as part of his internal policy programs, Skanderbeg issued many edicts, such as those on carrying out a census of the population and on tax collection, based on Roman and Byzantine law.

In literature and art

There are two known works of literature written about Skanderbeg which were produced in 15th century. The first was written at the beginning of 1480 by Serbian writer Martin Segon who was the Catholic Bishop of Ulcinj and one of the most notable 15th-century humanists.[132][133] A part of the text he wrote under title Martino Segono di Novo Brdo, vescovo di Dulcigno. Un umanista serbo-dalmata del tardo Quattrocento is short but very important biographical sketch on Skanderbeg (Template:Lang-it).[134][135] Another 15th century literature work with Skanderbeg as one of the main characters was Memoirs of a janissary (Template:Lang-sr) written in period 1490—1497 by Konstantin Mihailović, a Serb who was a janissary in Ottoman Army.[136][137]

Skanderbeg gathered quite a posthumous reputation in Western Europe. In the 16th and 17th centuries, most of the Balkans were under the suzerainty of the Ottomans who were at the gates of Vienna in 1683 and narrative of the heroic Christian's resistance to the "Moslem hordes" captivated readers' attention in the West.[123] Books on the Albanian prince began to appear in Western Europe in the early 16th century. One of the earliest was the Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi, Epirotarum Principis (Rome, 1508), published a mere four decades after Skanderbeg's death. This History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes was written by the Albanian historian Marinus Barletius Scodrensis, known in Albanian as Marin Barleti, who, after experiencing the Ottoman capture of his native Shkodër firsthand, settled in Padua where he became rector of the parish church of St. Stephan. Barleti dedicated his work to Don Ferrante Kastrioti, Skanderbeg's grandchild, and to posterity. The book was first published in Latin.[138] Barleti is sometimes inaccurate in favour of his hero, for example, according to Gibbon, Barleti claims that the Sultan was killed by disease under the walls of Krujë.[139] Barleti's inaccuracies had also been noticed prior to Gibbon by Laonikos Chalkokondyles.[140] He made up spurious correspondence between Vladislav II of Wallachia and Skanderbeg wrongly assigning it to the year 1443 instead to the year of 1444.[141] Barleti also invented correspondence between Skanderbeg and Sultan Mehmed II to match his interpretations of events.[142]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Barleti's book was translated into a number of foreign language versions. All these books, written in the panegyric style that would often characterize medieval historians who regarded history mostly as a branch of rhetoric, inspired a wide range of literary and art works.

Franciscus Blancus, a Catholic bishop born in Albania, also wrote Kastrioti's biography. His book "Georgius Castriotus, Epirensis vulgo Scanderbegh, Epirotarum Princeps Fortissimus" was published in Latin in 1636.[143] French philosopher, Voltaire, in his works, held in very high consideration the Albanian hero. Sir William Temple considered Skanderbeg to be one of the seven greatest chiefs without a crown, along with Belisarius, Flavius Aetius, John Hunyadi, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, Alexander Farnese, and William the Silent.[144] Ludvig Holberg, a Danish writer and philosopher, claimed that Skanderbeg was one of the greatest generals in history.[145]

The Italian baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi composed an opera entitled Scanderbeg (first performed 1718), libretto written by Antonio Salvi. Another opera, entitled Scanderbeg, was composed by 18th century French composer François Francœur (first performed 1763).[146] In the 20th century, Albanian composer Prenkë Jakova composed a third opera, entitled Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu, which premiered in 1968 for the 500th anniversary of the hero's death.[147]

Skanderbeg is the protagonist of three 18th-century British tragedies: William Havard's Scanderbeg, A Tragedy (1733), George Lillo's The Christian Hero (1735), and Thomas Whincop's Scanderbeg, Or, Love and Liberty (1747).[148] A number of poets and composers have also drawn inspiration from his military career. The French 16th-century poet Ronsard wrote a poem about him, as did the 19th-century American poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.[149] Gibbon, the 18th-century historian, held Skanderbeg in high regard with panegyric expressions.

Giammaria Biemmi, an Italian priest, published a work on Skanderbeg titled Istoria di Giorgio Castrioto Scanderbeg-Begh in Brescia, Italy in 1742.[150] He claimed that he had found a work published in Venice in 1480 and written by an Albanian humanist from Bar, in modern-day Montenegro[150] whose brother was a warrior in Skanderbeg's personal guard. According to Biemmi, the work had lost pages dealing with Skanderbeg's youth, the events from 1443–1449, the Siege of Krujë (1467), and Skanderbeg's death. Biemmi referred to the author of the work as Antivarino, meaning the man from Bar.[151] The "Anonymous of Antivari" was Biemmi's invention that some historians (Fan S. Noli and Athanase Gegaj) had not discovered and used his forgery as source in their works.[152]

Skanderbeg is also mentioned by Prince of Montenegro, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, one of the greatest poets of Serbian literature in his poem The Mountain Wreath (1847),[153] and in False Tsar Stephen the Little (1851).[154] In 1855, Camille Paganel wrote Histoire de Scanderbeg, inspired by the Crimean War,[155] whereas in the lengthy poetic tale Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–1819), Byron wrote with admiration about Skanderbeg and his warrior nation.

The Great Warrior Skanderbeg (Template:Lang-al, Template:Lang-ru), a 1953 Albanian-Soviet biographical film, earned an International Prize at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival.[156]

Skanderbeg's memory has been engraved in many museums, such as the Skanderbeg Museum next to Krujë Castle. Many monuments are dedicated to his memory in the Albanian cities of Tirana (in Skanderbeg Square by Odhise Paskali), Krujë, and Peshkopi. A palace in Rome in which Skanderbeg resided during his 1466–67 visits to the Vatican is still called Palazzo Skanderbeg and currently houses the Italian museum of pasta:[157] the palace is located between the Fontana di Trevi and the Quirinal Palace. Also in Rome, a statue is dedicated to the Albanian hero in Piazza Albania. Monuments or statues of Skanderbeg have also been erected in the cities of Skopje and Debar, in the Republic of Macedonia; Pristina, in Kosovo; Geneva, in Switzerland; Brussels, in Belgium; and other settlements in southern Italy where there is an Arbëreshë community. In 2006, a statue of Skanderbeg was unveiled on the grounds of St. Paul's Albanian Catholic Community in Rochester Hills, Michigan. It is the first statue of Skanderbeg to be erected in the United States.[158]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ There have been many theories on the place where Skanderbeg was born.[159] One of the main Skanderbeg biographers, Frashëri, has, among other, interpreted Gjon Muzaka's book of genealogies, sources of Raffaele Maffei, ("il Volterrano" (1451–1522)), and the Turkish defter (census) of 1467 and has placed the birth of Skanderbeg in the small village.[160]

- ^ On the reasons why the besieged had problems with the water in the castle primary sources disagree: While Barleti and Biemmi maintained that a dead dog was found in the castle well, and the garrison refused to drink the water since it might corrupt their soul, another primary source, an Ottoman chronicler, conjectured that the Ottoman forces found and cut the water sources of the castle. Recent historians mostly concur with the Ottoman chronicler's version.[161]

- ^ According to Barleti, a primary source, Skanderbeg and his three older brothers, Reposh, Kostandin, and Stanisha, were taken by the Sultan to his court as hostages. However, according to documents, besides Skanderbeg, only one of the brothers of Skanderbeg, probably Stanisha,[3] was taken hostage and had been conscripted into the Devşirme system, a military institute that would enroll Christian boys, convert them to Islam, and train them to become military officers.[162] Recent historians are of the opinion that while Stanisha might have been conscripted at a young age, and had to go through the Devşirme system, this was not the case with Skanderbeg, who is assumed to have been sent hostage to the Sultan by his father only at the age of 18.[19] It was in use at that time that in case of a military loss against the Sultan, a local chieftain would send one of his children at the Sultan's court, so that the child would be kept hostage for an unspecified time. The Sultan would this way exercise control in the area of the father by the hostage kept. The treatment of the hostage was not a bad one: Far from being a prison or anything similar, the sons taken hostage would be usually sent to the best military schools and trained to be future military leaders.[163]

- ^ Skanderbeg always signed himself as “Lord of Albania” (Template:Lang-la), and claimed no other titles but that in official documents.[164]

- ^ Authors have disagreed on whether Krujë belonged to Skanderbeg or to Alfonso V. While scholar Marinesco claimed in 1923 that Kruje no longer belonged Skanderbeg, but to Alfonso, who exercised his power through his viceroy,[165] this thesis has been rejected by scholar Athanas Gegaj in 1937, who claimed that the disproportion in numbers between the Spanish forces (100) and Skanderbeg's (around 10–15 thousand) clearly showed that the city belonged to Skanderbeg. Now what is generally accepted is that Skanderbegde facto had full sovereignty over his territories: while Naples' archives registered payments and supplies sent to Skanderbeg, they do not mention any kind of payment or tribute by Skanderbeg to Alfonso, except for various Turkish war prisoners and banners sent by him as a gift to the King.[95] Frashëri agrees with Gegaj in regards.[166]

- ^ In his response to Orsini, Skanderbeg mentioned that the Albanians never betray their friends, and that they are the descendants of Pyrrhus of Epirus. He also reminded Orsini of Pyrrhus' victories in southern Italy.[97][verification needed]

- ^ Since there is no birth documents for any of the children of Gjon Kastrioti, there has been disagreement between historians in relation to the year of birth of Skanderbeg until 1947, when Fan Noli's study on Skanderbeg placed the year of birth in 1405, which is now agreed upon by the majority of scholars[167]

- ^

- ^ The two villages are in Mavrovo and Rostuša Municipality, modern day Republic of Macedonia

Citations

- ^ Frazee 2006, p. 33

- ^ a b Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, p. 559, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5,

Skanderbeg declared himself the heir of Balšići and declared his intention to recover his inheritance

- ^ a b c Anamali 2002, p. 341

- ^ Nichols 2010, p. 329

- ^ Tennent 1845, p. 129

- ^ Moore 1850, p. 1

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 19

- ^ Masson 1954, p. 15

- ^ Hungarian Academy of Sciences 1985, p. 201[verification needed]

- ^ Michaelides, Constantine E. (2003-11-30). The Aegean crucible: tracing vernacular architecture in post-Byzantine centuries. Delos Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-9729723-0-7. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Bulletin d'archéologie et d'histoire dalmate (in Croatian), vol. 55–59, Split: Arheološki Muzej (Zadar); Arheološki Muzej (Split), p. 118, retrieved 30. November 2011,

Još treba istaći Skenderbegovo prezime Kastriot... To je svakako grčka izvedenica ... etnikum od castra

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ von Thallóczy, Ludwig (1916), Illyrisch-albanische Forschungen (in German), MÜNCHEN UND LEIPZIG: VERLAG VON DüNCKER & HUMBLOT, p. 80, OCLC 10224971,

Kastriot, die einen griechischen Namen führten, „Stadtbürger", kastriotis von kastron, Stadt (aus lat. castrum ; polis war nur Konstantinopel allein).

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hodgkinson 2005, p. 1

- ^ Rosser 2001, p. 363

- ^ Hodgkinson 2005, p. xix

- ^ Neubecker, Ottfried (1987). The Flags of Albania. The Flag bulletin. Vol. 26. Flag Research Center. p. 111. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

History records that the 15th century Albanian national hero, Skanderbeg (i.e. George Kastriota), had raised the red flag with the black eagle over his ancestral home, the Fortress of Kruje

- ^ Anamali 2002, p. 335

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 422 "Albanian vassals of the Ottomans — Koja Zakarija, Demetrius Jonima, John Castriot, and probably Tanush Major Dukagjin"

- ^ a b c Frashëri 2002, p. 86

- ^ a b Frashëri 2002, pp. 86–92

- ^ Sindik, Dušan (1990), "Dve povelje u Hilandaru o Ivanu Kastriotu i sinovima", Stanovništvo slovenskog porijekla u Albaniji : zbornik radova sa međunarodnog naučnog skupa održanog u Cetinju 21, 22. i 23. juna 1990 (in Serbian), Titograd: Istorijski institut SR Crne Gore ; Stručna knj., OCLC 29549273,

Повеља није датирана... Стога ће бити најбоље да се за датум издавања ове повеље задржи временски оквир између 1426. и 1431. године.... This act was not dated....Therefore it is best to assume that it was issued in period between 1426 and 1431.

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Anamali 2002, p. 342

- ^ Elsie 2010, p. 399

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 98

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 99

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 535

In 1432 Andrew Thopia revolted against his Ottoman overlords ... inspired other Albanian chiefs, in particular George Arianite (Araniti) ... The revolt spread ... from region of Valona up to Skadar... At this time, though summoned home by his relatives ... Skanderbeg did nothing, he remained ... loyal to sultan

- ^ a b c d Anamali 2002, p. 343

- ^ İnalcık 1995, p. 76

D'après le registre de l'an 1432, à Kruje on fait les subasi en ordre chronologique, les titulaires suivants : en 1432 Hizir Bey, en novembre 1438 encore Hizir Bey, en avril 1440 Umur Bey. Vers 1438 Iskender Bey, fils de Jean, avec le kadi de Kruje ont delivre des certificats (biti, mektub) sur des transfers de timar, operation qui indique que Iskander Bey (Scanderbeg le Kastriote) avait ete nomme subasi de Akcahisar (Kruje), avant que ne soit nomme a ce poste pour la deuxième fois Hizir Bey.)

- ^ İnalcık 1995, p. 77

La note en question, datée 1438, ne laisse subsister aucun doute que c'est autour de cette date que ces terres avaient été cadastrées. Les neuf villages en question, compte tenu qu'ils se trouvaient sur le Registre de Yuvan-ili (Jean Kastriote), sont du domaine du père de Skanderbeg. (The note, dated 1438, leaves no doubt that it is around this date that the land had been surveyed and registered. As the nine villages were listed on the Register of Yuvan-ili (John Kastrioti), they were definitely part of Skanderbeg's father's land.)

- ^ Francione 2003, p. 15

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 92

- ^ Zhelyazkova, Antonina. "Albanian identities". Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

In 1440, he was promoted to sancakbey of Debar

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|month=,|separator=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hösch, Peter (1972). The Balkans: a short history from Greek times to the present day, Volume 1972, Part 2. Crane, Russak. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8448-0072-1. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Frashëri 2002, pp. 130–133

- ^ Drizari 1968, p. 1

- ^ Setton 1976, p. 72 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSetton1976 (help)

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2001), Das venezianische Albanien (1392-1479) (in German), München: R. Oldenbourg Verlag GmbH München, ISBN 3-486-565699,

Georg Branković, Stefan Crnojević und Skanderbeg erschienen mit starken heeren vor den venezianischen Stadten (Georg Branković, Stefan Crnojević and Skanderbeg appeared with a strong army before the Venetian cities)

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|editorn-link=,|nopp=,|separator=,|laysummary=,|month=,|editorn-first=,|doi_inactivedate=,|chapterurl=,|editorn=,|author-separator=,|lastauthoramp=, and|editorn-last=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gibbon 1901, p. 464

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 212

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 135

- ^ a b c d e Hodgkinson 2005, p. 240

- ^ a b Frashëri 2002, p. 181

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 556 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFine1994 (help)

- ^ Gibbon 1788, p. 143

- ^ Stavrianos 1958, p. 64

- ^ Jacques 1995, pp. 179–180

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 21

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 144

- ^ Frashëri 1964, p. 72

- ^ a b Myrdal 1976, p. 48

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 40

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 557 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFine1994 (help)

- ^ a b Hodgkinson 1999, p. 102

- ^ Hodgkinson 1999, p. 85

- ^ a b Noli 1947, p. 26

- ^ a b Frashëri 2002, pp. 160–161

- ^ Vaughan, Dorothy Margaret (1954-06-01). Europe and the Turk: a pattern of alliances, 1350-1700. AMS Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780404563325. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. p. 393. ISBN 9780295972909. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Babinger 1992, p. 40 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBabinger1992 (help)

- ^ Kenneth, Setton (1997) [1978]. The papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Vol. II. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

Scanderbeg intended to go "peronalmente" with an army to assist Hunyadi, but was prevented from doing so by Branković, whose lands he ravaged as punishment for the Serbian desertion of the Christian cause.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel, Kosovo: A Short History, 1998, pp. 89-90

- ^ Nasse 1964, p. 24

- ^ Nasse 1964, p. 25

- ^ Francione 2003, p. 88

- ^ Setton, Kenneth M. (1976), The papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, American Philosophical Society, p. 101, ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9,

... among whom were Slavs, Germans, Italians and others

- ^ Babinger, Franz (1992), Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time, Princeton University Press, p. 60, ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6,

... including many Slavs, Italians, Frenchmen and Germans.

- ^ a b c Noli 1947, p. 25

- ^ Kenneth, Setton (1997) [1978]. The papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Vol. II. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

While the Venetians of Scutari sold food to the Turks, those of Durazzo aided the Albanians

- ^ Setton 1975, p. 272

- ^ Frashëri 2002, pp. 310–316

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2000). A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology, and folk culture. New York University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8147-2214-8.

- ^ Gjika, Ilirjan. "Manastiri i Ardenices" (in Albanian). Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Archive of Crown of Aragon, reg. 2691, 101 recto –102 verso; Zurita: Anales. IV, 29

- ^ Archive of Crown of Aragon, reg. 2697, 98—99

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 27

- ^ Marinesco 1923, pp. 69–79

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 558 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFine1994 (help)

- ^ Ljubić, Šime (1868–1891), Listine o odnošajih izmedju južnoga slaventsva i mletačke republike (Documents about the relations of South Slavs and Venetian Republic), XXV, vol. X, Zagreb, OCLC 68872994

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ASM, Carteggio gen. Sforzasco, ad annum 1454

- ^ "Magnifico et strenuo viro Georgio Castrioti, dicto Scandabech, gentium armorum magnanimo capitaneo, nobis plurimum dilecto" Noli 1947

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 30

- ^ "Magnifico et strenuo viro Georgio Castrioti, dicto Scandarbech, gentium armorum nostrarum in partibus Albanie generali capitaneo, consiliario fideli nobis dilecto" Noli 1947

- ^ Jorga 1908–1913, p. 46

- ^ Marinesco 1923, p. 82

- ^ a b c d e f g Noli 1947, p. 51

- ^ a b Frashëri 1964, p. 79

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 52

- ^ a b Noli 1947, p. 29

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 53

- ^ Frashëri 1964, p. 80

- ^ Anamali 2002, pp. 367–368

- ^ a b c d e Babinger 1992, pp. 152–153 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBabinger1992 (help)

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 359

- ^ Marinesco 1923, pp. 133–134

- ^ a b Gegaj 1937, p. 120 Cite error: The named reference "Gegaj1937p92" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Babinger 1992, p. 201 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBabinger1992 (help)

- ^ a b c Anamali 2002, p. 387

- ^ Noli 1947, p. 32

- ^ a b Frashëri 2002, pp. 370–390

- ^ a b c d Noli 1947, p. 35

- ^ Noli 1947, pp. 35–36

- ^ a b c d e Noli 1947, p. 36

- ^ İnalcık, Halil, From empire to republic : essays on Ottoman and Turkish social history, Istanbul: Isis Press, p. 88, ISBN 978-975-428-080-7, OCLC 34985150, retrieved 4. January 2012,

Balaban Aga, qui a accordé des timar à ses propres soldats dans la Basse- Dibra et dans la Çermeniça, ainsi qu'à son neveu à Mati, doit être ce même Balaban Aga, sancakbeyi d'Ohrid, connu pour ses batailles sanglantes contre Skanderbeg.

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b c Noli 1947, p. 37

- ^ a b c d Babinger 1992, pp. 251–253 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBabinger1992 (help)

- ^ Setton 1976, p. 282 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSetton1976 (help)

- ^ a b Housley 1992, p. 91

- ^ Drizari 1968, p. 85

- ^ a b c d e f g Noli 1947, p. 38

- ^ Stavrides 2001, pp. 163, 164

When the Ottoman army arrived Skanderbeg took refuge in Albanian mountains. Mehmed II sent Mahmud Pasha to the mountains, together with most experienced part of the army, in order to pursue Skanderbeg, while he himself ravaged the rest of the land ... The Grand Vezier spent fifteen days in the mountains,... However, they did not find Skanderbeg, who had managed to flee to the coast

- ^ Stavrides 2001, p. 163

...taking much booty and many prisoners... Mehmed II after ravaging the rest of the land, went to Kruje and besieged it for several days. When he realized that it would not be taken by assault, he decided to return...

- ^ a b Anamali 2002, pp. 411–412

- ^ Anamali 2002, pp. 411–413

- ^ Anamali 2002, pp. 413–416

- ^ Anamali 2002, pp. 416–417

- ^ Anamali 2002, pp. 417–420

- ^ Gibbon 1901, p. 467

- ^ a b Runciman 1990, pp. 183–185

- ^ Archivio del Gran Priorato di Napoli e Sicilia del Sovrano Militare Ordine di Malta, Napoli

- ^ Lane–Poole 1888, p. 135

- ^ Sedlar 1994, p. 396 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSedlar1994 (help)

- ^ Hodgkinson 2005, p. ix

- ^ a b c d Hodgkinson 2005, p. xii

- ^ Hodgkinson 2005, p. xiii

- ^ Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (2002), "... transformation of Skanderbeg into national symbol did not just serve national cohesion... in the national narrative Skanderbeg symbolised the sublime sacrifice of the Albanians in defending Europe from the Asiatic hordes.", Albanian identities: myth and history, Indiana University Press, p. 43

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|nopp=and|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kabashi, Artemida (2007). "Creation of Albanian National Identity". Balkanistica. 20. Slavica Publishers: 63.

The story of Scanderbeg ... rests at the heart of the Albanian nation, because it marks the creation of national identity for the Albanian people and their desire for freedom.

- ^ Gibbon 1901, p. 466

- ^ Cohen 2003, p. 151

- ^ Willson 1909, p. 296

- ^ Congressional Record, V. 151, Pt. 18, October 27 to November 7, 2005. Congress. 2005. p. 24057. ISBN 978-0-16-084826-1. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Elsie, Robert. Historical Dictionary of Kosova (European Historical Dictionaries). United States of America: Scarecrow Press Inc. p. 169. ISBN 0-8108-5309-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Zbornik Matice srpske za književnost i jezik (in Serbian). Novi Sad: Matica srpska. 1991. p. 91. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

Мартина Сегона, по сопственој изјави "српског писца"

- ^ Zgodovinski časopis, Vol. 54. Zgodovinsko društvo za Slovenijo. 2000. p. 131. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

Martin Segon je eden najvidnejših humanistov s konca 15. stoletja. Znano je, daje bil sin Jovana de Segonis iz Kotora in daje bil kanonik cerkve sv. Marije v znanem rudarskem mestu Novo Brdo.

- ^ Studi storici (in Italian). Istituto storico italiano per il medio evo. pp. 142–145. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

Narrazioni di Giorgio Castriotto, da i Turchi nella lingua loro chiamato Scander beg, cioe Alesandro Magno

- ^ UNVOLLSTÄNDIGER TEXTENTWURF ZUR DISKUSSION AM 6.2.2012 (PDF). 2012. p. 9. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

Martinus Segonus verfasste eine der frühesten „Landeskunden" des spätmittelalterlichen Balkans und eine kurze, aber sehr wichtige biographische Skizze zu Skanderbeg

[dead link] - ^ Živanović, Đorđe. "Konstantin Mihailović iz Ostrovice". Predgovor spisu Konstantina Mihailovića "Janičarove uspomene ili turska hronika" (in Serbian). Projekat Rastko, Poljska. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

Taj rukopis je... postao pre 1500. godine, a po svoj prilici još za vlade Kazimira Jagjelovića (1445-1492)....Kao što smo već rekli, Konstantin Mihailović je negde između 1497. i 1501. napisao jedino svoje književno delo, koje je sačuvano u raznim prepisima sve do naših dana....delo napisano verovatno između 1490. i 1497, i to zbog toga što se u njemu Matija Korvin spominje kao već mrtav, a poljski kralj Jan Olbraht kao živ.

- ^ Mihailović, Konstantin (1865) [1490—1501], Turska istorija ili kronika (Турска историја или кроника (Memoirs af a Janissary)) (in Serbian), vol. 18, Glasnik Srpskoga učenog društva (Serbian Learned Society), pp. 135, 140–145,

Глава XXXIV... спомиње се и Скендербег, кнез Епирски и Албански,....(Chapter XXXIV... there is mention of Skanderbeg, prince of Epirus and Albania)

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|editorn=,|editorn-first=,|doi_inactivedate=,|author-separator=,|coauthors=,|editorn-last=, and|editorn-link=(help) - ^ Minna Skafte Jensen, 2006,A Heroic Tale: Edin Barleti's Scanderbeg between orality and literacy

- ^ Gibbon 1901, p. 465

- ^ see Laonikos Chalkokondyles, l vii. p. 185, l. viii. p. 229

- ^ Setton, Kenneth (1976—1984), The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, vol. four volumes, American Philosophical Society, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9,

...... The spurious correspondence of July and August 1443, between Ladislas and Scanderbeg (made up by Barletius, who should assigned it to the year 1444) ...

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Setton, Kenneth (1976—1984), The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, vol. four volumes, American Philosophical Society, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9,

...... He also invented a correspondence between Skanderbeg and Sultan Mehmed II to fit his interpretations of the events in 1461—1463 ...

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Georgius Castriotus Epirensis, vulgo Scanderbegh. Per Franciscum Blancum, De Alumnis Collegij de Propaganda Fide Episcopum Sappatensem etc. Venetiis, Typis Marci Ginammi, MDCXXXVI (1636).

- ^ Temple 1705, pp. 285–286

- ^ Holberg on Scanderbeg by Bjoern Andersen

- ^ The Scanderberg Operas by Vivaldi and Francouer[dead link] by Del Brebner

- ^ Rubin, Don (2001), The world encyclopedia of contemporary theatre, Taylor & Francis, pp. 41–, ISBN 978-0-415-05928-2

- ^ Havard, 1733, Scanderbeg, A Tragedy; Lillo, 1735, The Christian Hero; Whincop, 1747, Scanderbeg, Or, Love and Liberty.

- ^ Longfellow 1880, pp. 286–296

- ^ a b Frashëri, Kristo (2002) (in Albanian), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, p. 9.

- ^ Frashëri, Kristo (2002) (in Albanian), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, p. 10.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth M. (1978), The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century, DIANE Publishing, p. 102, ISBN 0-87169-127-2,

Unfortunately Athanase Gegaj, L'Albanie et I'invasion turque au XV siecle, Louvain and Paris, 1937, pp. 77-80, had not discovered that the "Anonymous of Antivari" was an invention of Biemmi, nor had Noli even by 1947.

- ^ The Mountain Wreath, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian)

- ^ False Tsar Stephen the Little, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian)

- ^ Camille Paganel, 1855,"Histoire de Scanderbeg, ou Turcs et Chrétiens du XVe siècle"

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Great Warrior Skanderbeg". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "Palazzo Skanderbeg e la Cultura tradita" (in Italian).

- ^ Delaney, Robert (29 September 2006). "Welcoming Skanderbeg — Cd. Maida, Albanian president unveil statue of Albanian hero". The Michigan Catholic. Archdiocese of Detroit.[dead link]

- ^ Frashëri 2002, pp. 54–62

- ^ Frashëri 2002, pp. 62–66

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 158

- ^ Glassé 2008, p. 129

- ^ Zilfi 2010, p. 101

- ^ Anamali 2002, p. 379

- ^ Marinesco 1923, p. 59

- ^ Frashëri 2002, pp. 320–321

- ^ Frashëri 2002, pp. 72–77

References

- Anamali, Skënder (2002), Historia e popullit shqiptar në katër vëllime (in Albanian), vol. I, Botimet Toena, OCLC 52411919

- Babinger, Franz (1992), Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6

- Barletius, Marinus (1508), Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum Principis (in Latin), Bernardinus de Vitalibus, OCLC 645065473

- Barleti, Marin (1597), Coronica del esforçado principe y capitan Iorge Castrioto, rey de Epiro, ò Albania (in Spanish), Luis Sanchez, OCLC 20731044

- Blancum, Franciscus (1636) (in Latin) Georgius Castriotus, Epirensis vulgo Scanderbegh, Epirotarum Princeps Fortissimus, Propaganda Fide, Venice.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2007), Aux origines du nationalisme albanais: la naissance d'une nation (in French), Karthala, ISBN 978-2-84586-816-8

- Cohen, Richard (2003), By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions, Random House, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8129-6966-5

- De Lavardin, Jacques (1592), Histoire de Georges Castriot surnommé Scanderbeg, Roy d'Albanie: contenant ses illustres faicts d'armes & memorables victoires alencontre des Turcs, pour la foy de Jesus Christ. Le tout en douze livres. (in French), H. Haultin: La Rochelle, OCLC 560834149

- Drizari, Nelo (1968), Scanderbeg; his life, correspondence, orations, victories, and philosophy, National Press, OCLC 729093

- Elsie, Robert (2010) [2004], Historical Dictionary Of Albania (PDF), Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, ISBN 9781282521926, OCLC 816372706

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5

- Francione, Gennaro (2003), Skenderbeu: Një hero modern (in Albanian), Shtëpia botuese "Naim Frashëri", ISBN 9992738758

- Frashëri, Kristo (1964), The history of Albania: a brief survey, s.n., OCLC 1738885

- Frashëri, Kristo (2002), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468 (in Albanian), Botimet Toena, ISBN 99927-1-627-4

- Gegaj, Athanase (1937), L'Albanie et l'Invasion turque au XVe siècle (in French), Universite de Louvain, OCLC 652265147

- Gibbon, Edward (1788), The Analytical review, or History of literature, domestic and foreign, on an enlarged plan, vol. 2, OCLC 444861890

- Gibbon, Edward (1802), The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire, T. Cadell

- Gibbon, Edward (1901), The decline and fall of the Roman empire, P. F. Collier & Son, OCLC 317326240

- Glassé, Cyril (2008), The new encyclopedia of Islam, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-6296-7

- Hodgkinson, Harry (1999), Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, Centre for Albanian Studies, ISBN 978-1-873928-13-4

- Hodgkinson, Harry (2005), Scanderbeg: From Ottoman Captive to Albanian Hero, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-941-9

- Holberg, Ludwig (1739), Adskillige store heltes og beroemmelige maends, saer Orientalske og Indianske sammenlignede historier og bedrifter efter Plutarchi maade/ 2. (in Danish), Kjøbenhavn : Höpffner, 1739., OCLC 312532589

- Housley, Norman (1992), The later Crusades, 1274–1580: from Lyons to Alcazar, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-822136-4

- İnalcık, Halil (1995), From empire to republic: essays on Ottoman and Turkish social history, Isis Press, ISBN 978-975-428-080-7

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jacques, Edwin E. (1995), The Albanians: an ethnic history from prehistoric times to the present, McFarland, ISBN 978-0-89950-932-7

- Jorga, Neculai (1908–1913), Geschichte Des Osmanischen Reiches. Nach Den Quellen Dargestellt (in German), vol. II, OCLC 560022388

- Lane–Poole, Stanley (1888), The story of Turkey, G.P. Putnam's sons, OCLC 398296

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth (1880), Tales of a wayside inn, Houghton, Mifflin and Co., pp. 286–, OCLC 562689407

- Marinesco, Constantin (1923), "Alphonse V, roi d'Aragon et de Naples et l'Albanie de Scanderbeg", Mélanges de l'École roumaine en France (in French), I, OCLC 459949498

- Moore, Clement Clarke (1850), George Castriot, Surnamed Scanderbeg, King of Albania, New York: D. Appleton & Co., OCLC 397003