Arab Christians: Difference between revisions

→Classic antiquity: orthodox |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

===Classic antiquity=== |

===Classic antiquity=== |

||

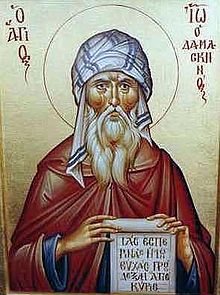

[[Image:Isaac the Syrian.jpg|thumb|[[Isaac of Nineveh]] a [[Bahrani people|Bahrani]] [[bishop]] and [[theologian]], 7th century ( |

[[Image:Isaac the Syrian.jpg|thumb|[[Isaac of Nineveh]] a [[Bahrani people|Bahrani]] [[bishop]] and [[theologian]], 7th century (orthodox [[icon]]).]] |

||

Arab Christians are [[indigenous people|indigenous]] to the [[Middle East]], with a presence there predating the 7th century [[Islamic]] expansion into the [[Fertile Crescent]]. There were many Arab tribes which adhered to Christianity beginning with the 1st century, including the [[Nabateans]] (who incorporated elements of both Arabs and [[Arameans]]), the [[Ghassanids]]<ref>[http://www.melkite.com/origins.html]</ref> and the [[Lakhmids]]. The latter were of [[Qahtanite|Qahtani]] origin and spoke Yemeni-Arabic as well as Greek, and who protected the south-eastern frontiers of the [[Roman Empire|Roman]] and [[Byzantine Empire]]s in north Arabia.{{Citation needed|date=February 2010}} |

Arab Christians are [[indigenous people|indigenous]] to the [[Middle East]], with a presence there predating the 7th century [[Islamic]] expansion into the [[Fertile Crescent]]. There were many Arab tribes which adhered to Christianity beginning with the 1st century, including the [[Nabateans]] (who incorporated elements of both Arabs and [[Arameans]]), the [[Ghassanids]]<ref>[http://www.melkite.com/origins.html]</ref> and the [[Lakhmids]]. The latter were of [[Qahtanite|Qahtani]] origin and spoke Yemeni-Arabic as well as Greek, and who protected the south-eastern frontiers of the [[Roman Empire|Roman]] and [[Byzantine Empire]]s in north Arabia.{{Citation needed|date=February 2010}} |

||

Revision as of 11:33, 10 May 2013

File:Michel Aflaq.jpg      | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 2,205,000[1] | |

| 520,000[2]-700,000[b][c] (also 52,000 Maronites) | |

| 390,000 [3] (also 1,000 Maronites) | |

| 10,000[4]-350,000[2][a] (also 6-11 million Copts and 5,000 Maronites) | |

| 350,000[2][b][c] (also 1.062 million Maronites) | |

| 122,000 [b] (also 1,000 Copts and 7,000 Maronites) | |

| 38,000[5]-50,000[6] | |

| 10,000[2][b] | |

| 10,000[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity: Greek Orthodox Arab Orthodox Greek Catholic Melkite Greek Catholic and other sects | |

[a].^ excluding Copts [c].^ excluding Maronites | |

Arab Christians (Arabic: العرب المسيحيين Al-'Arab Al-Masihiyin) are ethnic Arabs of Christian faith,[8] sometimes also including those, who are identified with Arab panethnicity. They are the remnants of ancient Arab Christian clans or Arabized Christians (Melchites). Many of the modern Arab Christians are descendants of pre-Islamic Christian Arabian tribes, namely the Kahlani Qahtani tribes of ancient Yemen (i.e. Ghassanids, Lakhmids, Banu Judham and Hamadan). During the 5th and 6th centuries the Ghassanids, who adopted Monophysite Christianity, formed one of the most powerful Arab confederations allied to Christian Byzantium, being a buffer against the pagan tribes of Arabia. The last king of the Lakhmids, Nu'man III, a client of the Sasanian (Persian) Empire in the late sixth century AD, also converted to Christianity (in this case, to the Nestorian sect).[9][verification needed] Arab Christians played important role in Al-Nahda, as a matter of fact Arab Christians formed the educated elite and the bourgeois class, they have a significant impact in politices and economic and culture, and most important figures of the Al-Nahda movement were Christian Arabs.[10] Today Arab Christians play important roles in the Arab world, and Christians are relatively wealthy, well educated, and politically moderate.[11]

Arab Christians, forming Greek Orthodox (including Arab Orthodox) and Latin Christian communities, are estimated to be 200,000 in Syria, a hundred thousand in Jordan and an equal number or more among the Palestinian Arab population and within the Arab-Israeli population,[12] with a sizeable community in Lebanon and marginal communities in Iraq and Egypt. Emigrants from Arab Christian communities make up a significant proportion of the Middle Eastern diaspora, with sizeable population concentrations across the Americas, most notably in Chile and the US. Arab Christians term is also generally applied to Arabized Melkite societies in Lebanon, Syria, Israel and the Palestinian Authority, who trace their roots to Greek and Aramaic-speaking Byzantine Christians.[citation needed] Some Arab Christians are a more recent end result of Evangelization.

Arab Christians are not the only Christian group in the Middle East, with significant non-Arab indigenous Christian communities of ethnic Armenians, Georgians, Greeks and others. Besides those, large ethno-religious Middle Eastern Christian groups of Copts, Maronites and Syriacs are being argued with a great deal of controversy whether their ethnic identity is Arab or not. Even though sometimes classified as Arab Christians, the largest Middle Eastern Christian groups of Lebanese Maronites and Egyptian Copts often claim non-Arab ethnicity: significant proportion of the Maronites claim descent from ancient Phoenicians, while some Egyptian Copts also eschew an Arab identity, preferring an Ancient Egyptian one. However, both Maronites and Copts had lost their linguistic differentiation during the Ottoman period in favor of the Arabic language. The Syriac Christian groups, composed largely of Chaldo-Assyrians, form the majority of Christians in Iraq, north east Syria, south-east Turkey and north-west Iran. They are generally defined as non-Arab ethnic groups, including by the governments of Iraq, Iran and Turkey. Assyro-Chaldeans are practicing their own native dialects of Syriac-Aramaic language, in addition to also speaking local Arabic dialects. Despite their ancient pre-Arabic roots and distinct linguo-cultural identities,[13] Assyro-Chaldeans are sometimes related by Western sources as "Christians of the Arab World" or "Arabic Christians", creating confusion about their identity.[14] Syriac Christians were also related as "Arab Christians" by pan-Arab movements and Arab-Islamic regimes against their will.[15][16]

History

Classic antiquity

Arab Christians are indigenous to the Middle East, with a presence there predating the 7th century Islamic expansion into the Fertile Crescent. There were many Arab tribes which adhered to Christianity beginning with the 1st century, including the Nabateans (who incorporated elements of both Arabs and Arameans), the Ghassanids[17] and the Lakhmids. The latter were of Qahtani origin and spoke Yemeni-Arabic as well as Greek, and who protected the south-eastern frontiers of the Roman and Byzantine Empires in north Arabia.[citation needed]

Nabateans were possibly among the first Arab tribes to arrive to Southern Levant in the first millennium BC. At first, they were converted to Judaism, during the expansion campaigns of the Hasmonean Kingdom at the first and second centuries BC. However, by the fourth century Nabateans had converted to Christianity.[18] The new Arab invaders, who soon pressed forward into their seats found the remnants of the Nabataeans transformed into peasants. Their lands were divided between the new Qahtanite Arab tribal kingdoms of the Byzantine vassals the Ghassanid Arabs and the Himyarite vassals the Kindah Arab Kingdom in North Arabia.

The tribes of Tayy, Abd Al-Qais, and Taghlib are also known to have included many Christians in the pre-Islamic period. The Yemenite city of Najran was a center of Arabian Christianity, made famous by the persecution by one of the kings of Yemen, Dhu Nawas, who was himself an enthusiastic convert to Judaism. The leader of the Arabs of Najran during the period of persecution, Al-Harith, was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church as St. Aretas. Some modern scholars suggest that Philip the Arab was the first Christian emperor of Rome.[19] By the 4th century a significant number of Christians occupied the Sinai peninsula, Mesopotamia and Arabia.

The New Testament has a biblical account of Arab conversion to Christianity recorded in the book of Acts. When St. Peter preaches to the people of Jerusalem, they ask, "And how is it that we hear, each of us in his own native language? [. . .] both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians—we hear them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God." (Acts 2:8, 11, English Standard Version).[20][verification needed] Arab Christians are thus one of the oldest Christian communities.

The first mention of Christianity in Arabia occurs in the New Testament as the Apostle Paul refers to his journey in Arabia following his conversion (Galatians 1: 15-17). Later, Eusebius of Caesarea discusses a bishop named Beryllus in the see of Bostra, the site of a synod c. 240 and two Councils of Arabia. Christians existed in Arab lands from at least the 3rd century onward.[19]

Also, there were Christian influences coming from Ethiopia in particular in pre-Islamic times, and some Hijazis (including a cousin of Muhammad's wife Khadijah, according to some sources) adopted this faith, while some Ethiopian Christians may have lived in Mecca.[21]

After Islamic conquest

Throughout many eras of history, Christians have co-existed fairly peacefully with their fellow non-Christian Arab neighbours, principally Muslims and Jews.[citation needed] Even after the rapid expansion of Islam from the 7th century onwards through the Islamic conquests, many Christians chose not to convert to Islam. Many scholars and intellectuals like Edward Said believed Christians in the Arab world have made significant contributions to the Arab civilization and still do. Some of the top poets at certain times were Arab Christians, and many Arab Christians were physicians, writers, government officials, and people of literature.[22]

However, there have been many periods of persecution also,[citation needed] and Christians were often subject to Jizyah, a discriminatory tax.[citation needed] As "People of the Book", Christians in the region are accorded certain rights under Islamic law (Shari'ah) to practice their religion, strictly conditioned, however, on paying a tax required from non-Muslims called 'Jizyah' (pronounced Jiz-ya), in form of either cash or goods. The tax was not levied on slaves, women, children, monks, the old, the sick,[23][24] hermits, or the poor.[25] In return, non-Muslim citizens were permitted to practice their faith, to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy, to be entitled to Muslim state's protection from outside aggression, to be exempted from military service and the zakat, a form of tax which is obligatory upon Muslim citizens.[26][27][28]

Role in Al-Nahda

Renaissance of Arab culture in the nineteenth century began in the wake of exit of Mohammed Ali Pasha from the Levant in 1840 and accelerated in the late nineteenth century. Beirut, Cairo, Damascus and Aleppo were the main centers of renaissance and this led to the establishment of schools,universities,Arab theater and printing presses. It also led to the renewal of literary, linguistic and poetic distinctiveness. The emergence of a politically active movement known as the "association" was accompanied by the birth of the idea of Arab nationalism and the demand for reformation of the Ottoman Empire. The emergence of the idea of Arab independence and reformation, led to the calling of the establishment of modern states based on the European-style. It was during this stage, that the first compound of the Arabic language was introduced and the printing in Arabic letters. In music, sculpture and history and the humanities generally, as well as economics, human rights, and a summary of the case that the cultural renaissance by the Arabs the late Ottoman rule was a quantum leap for them to post-industrial revolution,[29] and can not be limited to the fields of cultural renaissance of Arab in the nineteenth century these categories only as It is extended to include the spectrum of society and the fields as a whole,[30] and is almost universal agreement among historians on the role played by the Arab Christians in this renaissance, both in Mount Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and their role in the prosperity through participation not only from home but in the Diaspora also.[31] as the fact that Christians in the modern era the educated elite and the bourgeois class, making their contribution to the economic boom with a significant impact, as they were the owners of a significant impact in the cultural renaissance, and in the revolt against colonialism Pflm, writings, and their work.[32] is noteworthy for example, in the press sound Anjoa founder of the «mirror the Middle» in 1879 and the Secretary of Saal founder of the Journal of Law and George Michael Knight founder of the «Egyptian newspaper» in 1888 and Alexander Shalhoub founder of the Journal of the Sultanate in 1897 and Selim Takla and his brother Bishara Takla founding Al-Ahram newspaper,[33] and in the jurisprudence of the Arabic language The Abraham Yazigi Yazigi and Nassif and Peter Gardener. At the same time entered into by the Archbishop of Aleppo Mlatios grace of the first printing press letters to Arab Levant and continued in print until 1899. On the other hand, contributed to Arab Christians in fighting policy Turkification pursued by the Assembly of the Union and Progress and has emerged in Aleppo, in particular, Bishop Germanos Farhat and Father Boutros Tallawy, and the school was founded the Patriarchate in the prolific that came out a multitude of flags of the Arab at that point,[34] and played college Christian university of St. Joseph and the American University of Beirut and Al-Hikma University in Baghdad and other leading role in the development of civilization and Arab culture.[35] In Iraq, an active father Anastas Marie Carmelite, and in the literature mentioned Gibran Khalil Gibran and Mikhail Naima Lomé increase and Ameen Rihani and Shafiq Maalouf and Elias Farhat. The answer, in politics and Alazuri Shokri Ghanem and Jacob Abov, Faris Nimr and Boutros-Ghali, in Lebanon and Egypt. Given this growing Christian role in politics and culture, governments began to turn contains the Ottoman ministers from the Arab Christians and all of them epic in Lebanon. In the economic sphere, a number of Christian families, including Al Sursock and all stockist and all Websters in the Levant and all Sakakini, and all-Ghali, and all fixed in Egypt,[36] Thus, the Arab Middle East led the Muslims and Christians a cultural renaissance and national general despotism which formed Rkizath Society of Union and Progress and Policy Turkification, and established this renaissance as seen Paul Naaman "Arab Christians as one of the pillars of the region and not as a minority on the fringes.[37]

In the post-Ottoman era

Some of the most influential Arab nationalists were Arab Christians, like George Habash, founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Syrian intellectual Constantin Zureiq. Many Palestinian Christians were also active in the formation and governing of the Palestinian National Authority since 1992. The suicide bomber Jules Jammal, a Syrian military officer who blew himself up while ramming a French ship, was also an Arab Christian.

Arab Christians today

Egypt

If one excludes the Coptic Christians, the numbers of the Greek Orthodox Church adherents in Egypt, who are ethnically Greek and Arab, is rather small - on the order of several thousands each. There are several isolated Greek Orthodox communities, largely composed of Arabs, in the Sinai Peninsula, though the rest of Egypt also has tiny numbers of other than Copts minorities.

Most Egyptian Christians are Copts, who are mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Although Copts in Egypt speak Egyptian Arabic, many of them do not consider themselves to be ethnically Arabs, but rather descendants of the Ancient Egyptians. The Copts constitute the largest population of Christians in the Middle East, numbering between 6,000,000 and 11,000,000. The liturgical language of the Copts, the Coptic language, is a direct descendant of the Ancient Egyptian language. Coptic remains the liturgical language of all Coptic churches inside and outside of Egypt.

Iraq

If excluding Syriac groups, the Arab Christian community in Iraq is relatively small, and further dwindled due to the Iraq War to just several thousands. Most Arab Christians in Iraq belong traditionally to Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches and are concentrated in major cities such as Baghdad, Basra and Mosul.

The vast majority of the 400,000 Christians in Iraq are ethnic Assyrians (also called Chaldeans and Syriacs), who follow Syriac Christian churches, most notably the Chaldean Catholic, Assyrian, Syriac Catholic and Orthodox churches.[38] Some followers of Syriac Churches may also self-identify as Arabs in the pan-ethnic sense.

Israel

With 122,000 Arab Christians living in Israel, as Arab citizens of Israel, out of a total of 151,700 Christian citizens,[39] this is one of the biggest Arab Christian communities in the world. It is also the only Arab Christian community in the Middle East, which experiences a net population growth. Arab Christians form an 80% majority of the Christians in Israel, with smaller Christian communities of ethnic Russians, Greeks, Armenians, Maronites, Ukrainians and Assyrians. The majority of Arab Christians in Israel belong to the Greek Orthodox Church, with a sizable minority belonging to the Greek Catholic (Melkite) and Latin Churches. Other denominations are the Anglicans who have their cathedral church in the contested territory of East Jerusalem. Baptists in Israel are concentrated in the north of the country, and have four churches in the Nazareth area, and a seminary.

Some of the Arab Christians in Israel self-identify as Palestinian Arab Christians. Christian Arabs are considered to be the most educated community in Israel and they have attained more bachelor's degrees and academic degrees than Jewish, Muslims and Druze per capita.[40] Christian Arabs also have the highest rates of success in the matriculation examinations, both in comparison to the Muslims and the Druze and in comparison to all students in the Jewish education system.[40]

Jordan

Jordanian Christians are the among the oldest Christian community in the world[41] Christians have resided in Jordan since the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, early in the 1st century AD. Jordanian Christians now number at about 400,000 people, or 6% of the population of approximately 6,500,000, which is lower than the near 20% in the early 20th century. This is largely due to lower birth rates in comparison with Muslims and to a strong influx of Muslim immigrants from neighboring countries. Also, a larger percent of Christians compared to Muslims emigrate to western countries, resulting in a large Jordanian Christian diaspora.

Christians are well integrated in the Jordanian society and have a high level of freedom. Nearly all Christians belong to the middle or upper classes. Moreover, Christians enjoy more economic and social opportunity in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan than anywhere in the Middle East and North Africa, except for Lebanon. They have a disproportionately large representation in the Jordanian parliament (10% of the Parliament) and hold important government portfolios, ambassadorial appointments abroad, and positions of high military rank. Jordanian Christians are allowed by the public and private sectors to leave work to attend Divine Liturgy or Mass on Sundays. All Christian religious ceremonies are publicly celebrated. Christians have established good relations with the royal family and the various Jordanian government officials and they have their own ecclesiastic courts for matters of personal status.

Most native Christians in Jordan identify themselves as Arab, though there are also significant non-Arab Assyro-Chaldean, Syriac and Armenian ethnic groups in the country. Christian ex-Muslims are not permitted to legally convert, and do not enjoy the same rights as other Christians in Jordan.

Lebanon

The earliest indisputable tradition of Christianity in Lebanon can be traced back to Saint Maron in the 4th century, the founder of national and ecclesiastical Maronitism. Saint Maron adopted an ascetic, reclusive life on the banks of the Orontes river near Homs–Syria and founded a community of monks who preached the Gospel in the surrounding area. The Saint Maron Monastery was too close to Antioch, making the monks vulnerable to emperor Justinian II’s persecution. To escape persecution, Saint John Maron, the first Maronite patriarch-elect, led his monks into the Lebanese mountains; the Maronite monks finally settled in the Qadisha valley. During the Muslim conquest, Muslims persecuted the Christians, particularly the Maronites, with the persecution reaching a peak during the Umayyad caliphate. Nevertheless, the influence of the Maronite establishment spread throughout the Lebanese mountains and became a considerable feudal force.[42] After the Muslim Conquest, the Maronite Church became isolated and did not reestablish contact with the Church of Rome until the 12th century.[43] According to Kamal Salibi some Maronites may have been descended from an Arabian tribe, who immigrated thousands of years ago from the Southern Arabian peninsula. Salibi maintains "It is very possible that the Maronites, as a community of Arabian origin, were among the last Arabian Christian tribes to arrive in Syria before Islam".[43] Many Lebanese Christians reject this, however, seeing themselves instead as being of non-Arab origin.

Lebanon holds the largest number of Christians in the Arab world proportionally and falls just behind Egypt in absolute numbers. It is known that Christians made up between 65%-85% [42] of Lebanon's population before the Lebanese Civil War, if not more, and they still form 30%-38%[42] of the population today. The exact number of Christians is uncertain because no official census has been made in Lebanon since 1932. Lebanese Christians belong mostly to the Maronite Catholic Church and Greek Orthodox, with sizable minorities belonging to the Melkite Greek Catholics. Lebanese Christians are the only Christians in the Middle East with a sizeable political role in the country. The Lebanese president, half of the cabinet, and half of the parliament follow one of the various Lebanese Christian rites.

Palestine

Most of the Palestinian Christians identify themselves as Arab Christians culturally and linguistically, claiming descent from the early Jews and Gentiles, who converted to Christianity during the Roman and Byzantine rule, as well as Christian Ghassanid Arabs and Greeks who settled in the region since. Between 36,000-50,000 Christians live in the Palestinian Authority, most of whom belong to the Orthodox (Greek Orthodox and Arab Orthodox) and Catholic (including Melchite) churches. The majority of Palestinian Christians live in the Bethlehem, Ramallah and Nablus areas.[44]

Many Palestinian Arab Christians hold high-ranking positions in Palestinian society, particularly at the political and social levels. Israeli historian Benny Morris writes that Christian-Muslim relations constitute a divisive element in Palestinian society.[45]

Christian communities in the Palestinian Authority and the Gaza Strip have greatly dwindled over the last two decades. The causes of the Palestinian Christian exodus are widely debated.[46] Reuters reports that many Palestinian Christians emigrate in pursuit of better living standards,[44] while the BBC also blames the economic decline in the Palestinian Authority as well as pressure from the security situation upon their lifestyle.[47] The Vatican and the Catholic Church saw the Israeli occupation and the general conflict in the Holy Land as the principal reasons for the Christian exodus from the territories.[48] There have also been cases of persecution by radical Islamist elements, mainly in the Gaza Strip.[46] Palestinian Christian human rights activist Hanna Siniora has attributed local harassment against Christians to "little groups" of "hoodlums" rather than to the Hamas or Fatah governments. The West Bank barrier and restrictions on Palestinian movement were cited by the former Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs' chief liaison to Christians as the primary issues facing local Christians.[46]

The decline of the Christian community in the Palestinian controlled areas follow the general trend of Christian decline in the Muslim dominated Middle East.

In 2007, just before the Hamas takeover of Gaza, there were 3,200 Christians living in the Gaza Strip.[49] Half the Christian community in Gaza fled to the West Bank and abroad after the Hamas take-over in 2007.[50]

Syria

In Syria, according to the 1960 census, Christians formed just under 15% of the population (about 1.2 million people)Due to political reasons, no newer census has been taken since. Current estimates suggest that overall Christians comprise about 10% of the overall population (2,500,000), due to having lower birth rates and higher emigration rates than their Muslim compatriots. The Arab Christians in Syria are Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic, with some Roman Catholics.The largest Christian denomination in Syria is the Greek Orthodox church, formerly known as the Melkite church after the 5-6th centuries Christian split, in which they stayed loyal to Constantinople ("melek" = king, is the Aramaic denomination for the Byzantine Emperor). The appellation "Greek" refers to the liturgy they use, sometimes used to refer to the ancestry and ethnicity of the members, however not all members are of Greek ancestry; in fact the Arabic word used is "Rum", which means "Byzantines", or Eastern Romans. Overall, the term is generally used to refer mostly to the Greek liturgy, and the Greek Orthodox denomination in Syria. Arabic is now its main liturgical language. Today, a minority of Syrian Christians hold on to their ethnic Syriac (also called Assyrians, Chaldo-Assyrians or Arameans), Antiochian Greek, and Armenian origins, with a major influx of Iraqi Christian refugees into these communities.

Turkey

Antiochian Greeks who mostly live in Hatay Province, are one of the Arabic speaker community in Turkey. They are Greek Orthodox. However, they are known as Arab Christians, because of their language. Antioch (capital of Hatay Province) is also historical capital of Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch

Diaspora

Hundreds of thousands of Arab Christians also live in the diaspora, outside of the Middle East. These are residing in such countries as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, the United States and Venezuela among them. There are also many Arab Christians in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom, France (due to its historical connections with Lebanon and North Africa), and Spain (due to its historical connections with northern Morocco), and to a lesser extent in Ireland, Germany, Italy, Greece and the Netherlands. Among those, across Europe and the Americas, an estimated 400,000 Arab Christians are living in the Palestinian diaspora.

North Africa

There are tiny communities of Roman Catholics in Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, and Morocco due to colonial rule - French rule for Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, Spanish rule for Morocco, and Italian rule for Libya. Most Christians in North Africa are foreign missionaries, immigrant workers, and people of French, Spanish, and Italian colonial descent. These mostly converted during the modern era or under French colonialism. Arguably, many more North African Christians of Berber or Arab descent live in France than in North Africa, due to the exodus of the pieds-noirs in the 1960s. Charles de Foucauld was renowned for his missions in North Africa among Muslims, including African Arabs.

Question of identity

Arab Christians include descendants of ancient Arab tribes, who were among the first Christian converts, as well as some recent adherents of Christianity. Sometimes, however the issue of self-identification arises regarding specific Christian communities across the Arab world.

Assyrians

After the ascend of the nationalist Ba'ath party in Iraq in 1963 Assyrian Christians were referred to as "Arab Christians" by Arab nationalists who deny the existence of a distinct Assyrian identity. In 1972 a law was passed to use Syriac language in public schools and in media, shortly afterwards however Syriac was banned and Arabic was imposed on Syriac language magazines and newspapers.[51]

By the time of the 1977 census, Assyrians were being referred to as either Arabs or Kurds. Christians were forced to deny their identity as Assyrian nationalism was harshly punished. One example of this "Arabization" program was Iraqi deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz, a Chaldean Christian who changed his surname from Youkhana upon joining the Baath.[52]

By the 1990s those Christians who still referred to themselves as "Assyrians" were exempt from the Oil-for-Food program and did not receive their monthly food rations.[52] Many Assyrians were expelled from their villages in northern Iraq, others were forced to replaced their names with Arab ones.[53]

They likewise pointed out that Arab nationalist groups have wrongly included Assyrian-Americans in their head count of Arab Americans, in order to bolster their political clout in Washington. Some Arab American groups have imported this denial of Assyrian identity to the United States. In 2001, a coalition of Assyrian, Chaldean and Maronite organizations, wrote to the Arab-American Institute, to reprimand them for claiming that Assyrians were Arabs. The asked the Arab-American Institute "to cease and desist from portraying Assyrians and Maronites of past and present as Arabs, and from speaking on behalf of Assyrians and Maronites."[52][54]

Copts

The Copts are the native Egyptian Christians, a major ethnoreligious group in Egypt. Christianity was the majority religion in Roman Egypt during the 4th to 6th centuries and until the Muslim conquest[55] and remains the faith of a significant minority population. Their Coptic language is the direct descendant of the Demotic Egyptian spoken in the Roman era, but it has been near-extinct and mostly limited to liturgical use since the 18th century. In current times the spoken language of Copts is Arabic, and a significant number of Coptic Christians self-identify as part of the Arab nation.

Copts in Egypt constitute the largest Christian community in the Middle East, as well as the largest religious minority in the region, accounting for an estimated 10% of Egyptian population.[56] Most Copts adhere to the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[57][58][59] The remaining (around 800,000) are divided between the Coptic Catholic and various Coptic Protestant churches.

As a religious minority, the Copts are subject to significant discrimination in modern Egypt, and the target of attacks by militant Islamic extremist groups.

Maronites

At the March 1936 Congress of the Coast and Four Districts, the Muslim leadership at this conference made the declaration that Lebanon was an Arab country, indistinguishable from its Arab neighbors. In the April 1936 Beirut municipal elections, Christian Maronite and Muslim Politicians were divided along Phoenician and Arab lines in concern of whether the Lebanese coast should be claimed by Syria or given to Lebanon, increasing the already mounting tensions between the two communities.[60]

Lebanese nationalism, which rejects Arab identity, has found a strong support among some Maronites and even other Orthodox Christians. However, this form of nationalism, nicknamed Phoenicianism, never developed into an integrated ideology led by key thinkers, but there are a few who stood out more than others: Charles Corm, Michel Chiha, and Said Aql in their promotion of Phoenicianism.[61]

In post civil-war Lebanon, since the Taif agreement, politically Phoenicianism, as an alternate to Arabism, has been restricted to a small group.[62] Phoeniciansm is deeply disputed by some scholars, who have on occasion tried to convince these claims are false and to embrace and accept the Arab identity instead.[63][64] This conflict of ideas of an identity is believed to be one of the main pivotal disputes between the Muslim and Maronite Christian populations of Lebanon and what mainly divides the country from national unity.[65] It's generalized that Muslims focus more on the Arab identity of Lebanese history and culture whereas Christians focus on the pre-arabized & non-Arab spectrum of the Lebanese identity and rather refrain from the Arab specification.[66]

During a final session of the Lebanese Parliament, a Marada Maronite MP states his identity as an Arab: "I, the Maronite Christian Lebanese Arab, grandson of Patriarch Estefan Doueihy, declare my pride to be a part of our people’s resistance in the South. Can one renounce what guarantees his rights?"[67]

Pan-Syrian identity

Although the majority of the followers of Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches in the Levant adhere to Arab nationalism, some politicians reject Arabism, such as the secular Greek Orthodox Antun Saadeh, founder of the SSNP, who was executed for advocating the abolition of the Lebanese state by the Kataeb led government in the 1940s. Saadeh rejected Arab Nationalism (the idea that the speakers of the Arabic language form a single, unified nation), and argued instead for the creation of the state of United Syrian Nation or Natural Syria encompassing the Fertile Crescent. Saadeh rejected both language and religion as defining characteristics of a nation, and instead argued that nations develop through the common development of a people inhabiting a specific geographical region. He was thus a strong opponent of both Arab nationalism and Pan-Islamism. He argued that Syria was historically, culturally, and geographically distinct from the rest of the Arab world, which he divided into four parts. He traced Syrian history as a distinct entity back to the Phoenicians, Canaanites, Arameans, Babylonians etc.[68]

Church affiliation

The Arab Christians largely belong to the Greek Orthodox or Antiochian Orthodox Churches, though there are also adherents to other churches: Melkite Greek Catholic Church, Latin Catholic Church, and Protestant Churches.

Doctrine

Like Arab Muslims, Arab Christians refer to God as Allah, as an Arabic word for "God".[69][70] The use of the term Allah in Arab Christian churches predates Islam by several centuries.[69] In more recent times (especially since the mid-19th century), some Arab speaking Christians from the Levant region have been converted from these native, traditional churches to more recent Protestant ones, most notably Baptist and Methodist churches[citation needed]. This is mostly due to an influx of Western, predominantly American Evangelical, missionaries.

Genetic Studies

Relation of Levantine populations to Phoenicians

A study in the genetic marker of the Phoenicians led by Pierre Zalloua, showed that the Phoenician genetic marker was found in 1 out of 17 males in the region surrounding the Mediterranean and Phoenician trading centers such as the Levant, Tunisia, Morocco, Cyprus, and Malta. The study focused on the male Y-chromosome of a sample of 1,330 males from the Mediterranean. Colin Groves, biological anthropologist of the Australia National University in Canberra says that the study does not suggest that the Phoenicians were restricted to a certain place, but that their DNA still lingers 3,000 years later.[71][72]

In Lebanon, almost 1 in 3 of Lebanese carry the Phoenician gene in their DNA. This Phoenician signature is distributed equally among different groups (both Christians and Muslims) in Lebanon and that the overall genetic makeup of the Lebanese was found to be similar across various backgrounds.[73] The Phoenician gene in this study refers to haplogroup J2 plus the haplotypes PCS1+ to PCS6+, however the study also states that the Phoenicians also likely had other haplogroups.[74]

In addition, the study found that the J2 ("old levantine haplogroup") was found in an "unusually high proportion" (about 20-30%) among Levantine people such as the Syrians, Lebanese and the Palestinians.[75] The ancestor haplogroup J is common to about 50% of the Arabic-speaking people of the Southwest Asian portion of the Middle East. A Lebanese Christian who was tested as having the J2 haplogroup stated that "It carries no big meaning," and added he views himself as "Lebanese, Arab and Christian -- in that order."[75]

See also

- Antiochian Greeks

- List of Christian terms in Arabic

- Bible translations (Arabic)

- Taghlib

- Sophronius

- John of Damascus

References

- ^ http://www.aaiusa.org/pages/demographics/

- ^ a b c d "Christians of the Middle East - Country by Country Facts and Figures on Christians of the Middle East". Middleeast.about.com. 9 May 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-15239529

- ^ "Who are Egypt's Christians?". BBC News. 26 February 2000.

- ^ "The Beleaguered Christians of the Palestinian-Controlled Areas, by David Raab". Jcpa.org. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Minority Rights Group International : Turkey : Rum Orthodox Christians". Minorityrights.org. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ [2] "First, they are not recognized as distinct ethnic identities, but rather as segments from the wide "Arab nation" who are "of Christian faith."

- ^ Philip K. Hitti. History of the Arabs. 6th ed.; Macmillan and St. Martin's Press, 1967, pp. 78-84 (on the Ghassanids and Lakhmids) and pp. 87-108 (on Yemen and the Hijaz).

- ^ [3] "The historical march of the Arabs: the third moment."

- ^ Pope to Arab Christians: Keep the Faith.

- ^ [4]

- ^ http://www.cambriapress.com/abi/9781604975833abi.pdf

- ^ [5] "In spite of the widespread geographical imaginations of the Middle East as an Arabic and Islamic monolith, supported by Western mass media and some Middle Eastern states high politicians, the Middle East is quite a heterogeneous region. This region comprises numerous ethnic national, religious, linguistic or ethno-religious groups."

- ^ [6] "Arab-Islamic regimes in the region assert that all those Christians who live within the confines of 'Arab borders' are 'Arab'."

- ^ [7] "Assyrians are an ethnically, linguistically and religiously distinct minority in the Middle Eastern region."

- ^ [8]

- ^ Rimon, Ofra. "The Nabateans in the Negev". Hecht Museum. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ a b Parry, Ken (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA.: Blackwell Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 0-631-23203-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Arab Christians: An Endangered Species". Jerusalemites.org. 18 March 1999. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs, 6th ed. (Macmillan and St. Martin's Press, 1967, pp. 78-84 (on the Ghassanids and Lakhmids) and pp. 87-108 (on Yemen and the Hijaz).

- ^ http://thechristianarabs.com

- ^ Shahid Alam, Articulating Group Differences: A Variety of Autocentrisms, Journal of Science and Society, 2003

- ^ Seed, Patricia. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640, Cambridge University Press, 27 October 1995, pp. 79-80.

- ^ Ali, Abdullah Yusuf (1991). The Holy Quran. Medina: King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex.

- ^ John Louis Esposito, Islam the Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 15 January 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 10, 20

- ^ Ali, Abdullah Yusuf (1991). The Holy Quran. Medina: King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex, pg. 507

- ^ المسيحيون العرب: طليعة النهضة وهمزة وصل التقدم، موقع القديسة تيريزا، 14 نوفمبر 2011.

- ^ دور المسيحيين العرب المشارقة في تحديث العالم العربي، كنائس لبنان، 14 نوفمبر 2011.

- ^ دور الموارنة أحد ضرورات مستقبل المنطقة، أصول، 14 نوفمبر 2011.

- ^ عروبة المسيحيين ودورهم في النهضة

- ^ تاريخ الكنائس الشرقية، مرجع سابق، ص.111

- ^ محطات مارونية من تاريخ لبنان، مرجع سابق، ص.183

- ^ دور العرب المسيحيين المشارقة فــي تحديث العالم العربي

- ^ الشوام في مصر... وجود متميز خـــــــــلال القـرنين التاسع عشر والعشرين

- ^ محطات مارونية من تاريخ لبنان، مرجع سابق، ص.185

- ^ "Guide: Christians in the Middle East". BBC. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Statistical Abstract of Israel 2010, table 2.2, see http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/shnatone_new.htm?CYear=2010&Vol=61&CSubject=2

- ^ a b Christians in Israel

- ^ Address to H.H. Pope Benedict XVI at the King Hussein Mosque, Amman, Jordan By: H.R.H. Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad bin Talal

- ^ a b c "THE LEBANESE CENSUS OF 1932 REVISITED. WHO ARE THE LEBANESE?". yes. Source: British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Nov99, Vol. 26 Issue 2, p219, 23p. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b Salibi, Kamal., A house of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered., University of California Press., Berkeley, 1988. p. 89

- ^ a b Nasr, Joseph (10 May 2009). "FACTBOX - Christians in Israel, West Bank and Gaza". Reuters.

- ^ The birth of the Palestinian refugee problem revisited, Benny Morris

- ^ a b c Derfner, Larry (7 May 2009). "Persecuted Christians?". The Jerusalem Post.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Guide: Christians in the Middle East. BBC News. 2011-10-11.

- ^ jpost.com

- ^ Palestinian Christian activist stabbed to death in Gaza Haaretz

- ^ Micheal Oren.Israel and the plight of Mideast Christians. Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Indigenous People in Distress, Fred Aprim

- ^ a b c Lewis, J. L. (Summer 2003). "Iraqi Assyrians: Barometer of Pluralism". Middle East Quarterly: 49–57. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ "Iraq: Information on treatment of Assyrian and Chaldean Christians". United States Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Coalition of American Assyrians and Maronites Rebukes Arab American Institute, AINA.org

- ^ Ibrahim, Youssef M. (18 April 1998). "U.S. Bill Has Egypt's Copts Squirming". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Cole, Ethan (8 July 2008). "Egypt's Christian-Muslim Gap Growing Bigger". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Egypt from "U.S. Department of State/Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs"". United States Department of State. 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Egypt from "Foreign and Commonwealth Office"". Foreign and Commonwealth Office -UK Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 15 August 2008.

- ^ Who are the Christians in the Middle East?. Betty Jane Bailey. 18 June 2009. ISBN 978-0-8028-1020-5.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ The Middle East: From Transition to Development By Sami G. Hajjar

- ^ Kemal Salibi, A House of Many Mansions.

- ^ "The Identity of Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church: Easton, Pennsylvania & Kfarsghab, Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "The vote of confidence debate – final session | Ya Libnan | World News Live from Lebanon". LB: Ya Libnan. 11 December 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "المكتبة السورية القومية الاجتماعية". Ssnp.Com. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ a b Timothy George (2002). Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?: understanding the differences between Christianity and Islam. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-24748-7.

- ^ Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz (2007). The colors of Jews: racial politics and radical diasporism (Illustrated, annotated ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21927-5.

- ^ "Photo: Phoenician Blood Endures 3,000 Years, DNA Study Shows". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (31 October 2008). "DNA legacy of ancient seafarers". BBC News. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Antelava, Natalia (20 December 2008). "Divided Lebanon's common genes". BBC News. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Haplogroup J2, in general, and haplotypes PCS1+ through PCS6+ therefore represent lineages that might have been spread by the Phoenicians... We do not suggest that the Phoenicians spread only or predominantly J2 and PCS1+ through PCS6+ lineages. They are likely to have spread many lineages from multiple haplogroups" [9]

- ^ a b "In Lebanon DNA may yet heal rifts | Reuters". Uk.reuters.com. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2010.