7 (New York City Subway service): Difference between revisions

m →Resumption of express service: grammar/usage - 'riders' is a countable noun |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 347: | Line 347: | ||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

* The 2000 [[documentary film]] ''The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey'' is based on the ethnic diversity of the people that ride the '''7''' train every day.<ref>See also: {{IMDb title|0229936|The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey}}</ref> |

* The 2000 [[documentary film]] ''The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey'' is based on the ethnic diversity of the people that ride the '''7''' train every day.<ref>See also: {{IMDb title|0229936|The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey}}</ref> |

||

* [[The 7 Line Army]] is a group of [[New York Mets]] fans whose name is derived from the '''7''' route. |

* [[The 7 Line Army]] is a group of [[New York Mets]] fans whose name is derived from the '''7''' route.{{cite news|url=http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2013/03/26/860-mets-fans-strong-opening-day-just-the-start-for-the-7-line-army/|title=860 Mets Fans Strong, Opening Day Just The Start For ‘The 7 Line Army’|date=March 26, 2013|first=Chris|last=Colton|publisher=[[WCBS-TV]]}} |

||

* In a 1999 interview, then–[[Atlanta Braves]] pitcher [[John Rocker]] gave a [[John Rocker#Controversies|scathing review]] of the '''7''' train, of New York City, and of Mets fans.<ref>{{cite web | title=At Full Blast Shooting outrageously from the lip, Braves closer John Rocker bangs away at his favorite targets: the Mets, their fans, their city and just about everyone in it | website=Vault | date=December 27, 1999 | url=https://www.si.com/vault/1999/12/27/271860/at-full-blast-shooting-outrageously-from-the-lip-braves-closer-john-rocker-bangs-away-at-his-favorite-targets-the-mets-their-fans-their-city-and-just-about-everyone-in-it | access-date=November 29, 2018}}</ref> |

* In a 1999 interview, then–[[Atlanta Braves]] pitcher [[John Rocker]] gave a [[John Rocker#Controversies|scathing review]] of the '''7''' train, of New York City, and of Mets fans.<ref>{{cite web | title=At Full Blast Shooting outrageously from the lip, Braves closer John Rocker bangs away at his favorite targets: the Mets, their fans, their city and just about everyone in it | website=Vault | date=December 27, 1999 | url=https://www.si.com/vault/1999/12/27/271860/at-full-blast-shooting-outrageously-from-the-lip-braves-closer-john-rocker-bangs-away-at-his-favorite-targets-the-mets-their-fans-their-city-and-just-about-everyone-in-it | access-date=November 29, 2018}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:42, 28 March 2019

Flushing Local Flushing Express | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern end | Flushing–Main Street | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern end | 34th Street–Hudson Yards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 22 (local service) 12 (express service) 8 (super express service) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | R188[1][2] (Rolling stock assignments subject to change) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depot | Corona Yard | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Started service | 1915 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

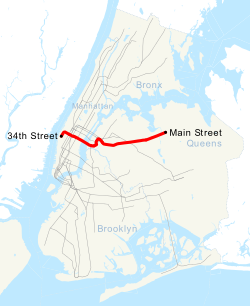

The 7 Flushing Local and <7> Flushing Express[3] are two rapid transit services in the A Division of the New York City Subway, providing local and express services along the full length of the IRT Flushing Line. Their route emblems, or "bullets", are colored purple, since they serve the Flushing Line.[4]

Local service is denoted by a (7) in a circular bullet, and express service is denoted by a <7> in a diamond-shaped bullet. Several cars also feature LED signs around the service logo to indicate local or express service to riders; a green circle denotes 7 local trains and a red diamond denotes <7> express trains.

7 trains operate at all times between Main Street in Flushing, Queens and 34th Street–Hudson Yards in Chelsea, Manhattan. Local service operates at all times, while express service runs only during rush hours and early evenings in the peak direction and during special events.

The 7 route started running in 1915 when the Flushing Line opened. Since 1927, the 7 has held largely the same route, except for a one-stop western extension from Times Square to Hudson Yards in 2015.

Service history

Early history

On June 13, 1915, the first test train on the IRT Flushing Line ran between Grand Central and Vernon Boulevard–Jackson Avenue, followed by the start of revenue service on June 22.[5] The Flushing Line was extended one stop from Vernon–Jackson Avenues to Hunters Point Avenue on February 15, 1916.[6][7] On November 5, 1916, the Flushing Line was extended two more stops to the east to the Queensboro Plaza station.[8][9][7] The line was opened from Queensboro Plaza to Alburtis Avenue on April 21, 1917.[10][11][12][13] Service to 111th Street was inaugurated on October 13, 1925, with shuttle service running between 111th Street and the previous terminal at Alburtis Avenue (now 103rd Street–Corona Plaza) on the Manhattan-bound track.[14][15]

The line was extended to Willets Point Boulevard on May 7, 1927,[16][17]: 13 with service provided by shuttle trains until through service was inaugurated on May 14.[18][19] On March 22, 1926, the line was extended one stop westward from Grand Central to Fifth Avenue.[20][21]: 4 The line was finally extended to Times Square on March 14, 1927.[17]: 13 [22] The eastern extension to Flushing–Main Street opened on January 21, 1928.[23]

The service on the Flushing Line east of Queensboro Plaza was shared by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company and the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation from 1912 to 1949; BMT trains were designated 9, while IRT services were designated 7 on maps only. The 7 designation was assigned to trains since the introduction of the front rollsigns on the R12 in 1948.[24]

Introduction of express service

Express trains began running on April 24, 1939 to serve the 1939 New York World's Fair.[25] The first train left Main Street at 6:30 a.m.. IRT expresses ran every nine minutes between Main Street and Times Square while BMT expresses ran every minutes between Main Street and Queensboro Plaza. The running time between Main Street and Queensboro Plaza was 15 minutes and the running time between Main Street and Times Square was 27 minutes. Express service to Manhattan operated in the AM rush between 6:30 and 10:$3 a.m.. Express service to Main Street began from Times Square for the IRT at 10:50 a.m. and the BMT from Queensboro Plaza at 11:09, continuing until 8 p.m..[26]

On October 17, 1949, the joint BMT/IRT operation of the Flushing Line ended, and the Flushing Line became the responsibility of the IRT.[27] After the end of BMT/IRT dual service, the New York City Board of Transportation announced that the Flushing Line platforms would be lengthened to 11 IRT car lengths, and the Astoria Line platforms extended to 10 BMT car lengths. The project, to start in 1950, would cost $3.85 million. The platforms were only able to fit nine 51-foot-long IRT cars, or seven 60-foot-long BMT cars beforehand.[28]

In 1953, with increased ridership on the line, a "super-express" service was instituted on the line.[29] The next year, the trains were lengthened to nine cars each. Subsequently, the trains were extended to ten cars on November 1, 1962. With the 1964–1965 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in April 1964, trains were lengthened to eleven cars.[30][31] The Flushing Line received 430 new R33 and R36 "World's Fair" cars for this enhanced service.[32]: 137

On March 12, 1953, two nine-car super express trains began operating from Flushing–Main Street to Times Square in the AM rush hour. The super expresses stopped at Main Street, and Willets Point before skipping all stops to Queensboro Plaza, bypassing the Woodside and Junction Boulevard express stops. The running time was cut down to 23 minutes from 25 minutes.[33] Beginning August 12, 1955, four super expresses operated during the AM rush hour.[34] On September 10, 1953, two express trains from Times Square were converted to super express trains in the PM rush hour.[29] Super express service was discontinued in the AM rush and PM rush, on January 13, and December 14, 1956, respectively.[35]

Holiday and Saturday express service was discontinued on March 20, 1954.[36] At some point afterwards, weekday midday express service was discontinued, but was restored on November 29, 1971, before being discontinued again by August 29, 1975.

On November 1, 1962, fifty R17s (#6500-6549) were transferred from the Mainline IRT to the 7, allowing for ten-car operation. This was the first time that the IRT ran ten-car trains without a second conductor.[37] With the 1964–1965 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in April 1964, trains were lengthened to eleven cars.[30][31] The Flushing Line received 430 new R33 and R36 "World's Fair" cars for this enhanced service.[32]: 137

Rehabilitation

First renovation

From May 13, 1985, to August 21, 1989, the IRT Flushing Line was overhauled for improvements, including the installation of new track, repair of station structures and to improve line infrastructure. The project cost $70 million.[38] The major element was the replacement of rails on the Queens Boulevard viaduct. This was necessitated because the subway was allowed to deteriorate during the 1970s and 1980s to the point that there were widespread "Code Red" defects on the Flushing Line, and there were some pillars holding elevated structures that were so shaky that trains wouldn't run if the wind exceeded 65 mph. <7> express service was suspended for the duration of the project; however, extra 7 service was provided for Mets games and Flushing Meadows Park events. During the project, delays of up to 10 minutes on weekdays, and 20 minutes on weekends were expected. The New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) had considered running express bus service to replace <7> express service, but decided against it as it would require hundreds of buses, which the NYCTA did not have. During the construction project, the NYCTA operated 25 trains per hour on the local track, three fewer than the 28 trains per hour split between the local and express beforehand. Running times on the 7 were lengthened by ten minutes during the project.[39]

Resumption of express service

The project was completed in June 1989, six months ahead of its scheduled completion of December 1989. The NYCTA held a public hearing on June 29, 1989 concerning its proposed reinstatement of express service. The NYCTA proposed implementing express service in July 1989 to coincide with the regular A Division schedules. It began to plan options to reinstate express service in 1988. Options were presented to local community boards, including the service pattern in place before May 1985, the continuation of all-local service, Super Express service running nonstop between Willets Point and Queensboro Plaza and Skip-Stop Express service.[40]

Before May 1985, express service operated to Manhattan from 6:30 a.m. to 9:45 a.m. and to Main Street from 3:15 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.. Expresses ran every three minutes and locals ran every six minutes. This split between expresses and locals was in place due to high demand for express trains. Express trains operated every two minutes, and then every four minutes due to the uneven split in service. Express trains following the four minute intervals carried twice as many passengers than the expresses following the two minute intervals. With the elimination of express service and the unreliable merge at 33rd Street–Rawson Street, service reliability increased, with on-time performance often exceeding 95%.[40]

Keeping local-only service was dismissed as it would not have saved times for the large number of riders boarding east of Junction Boulevard heading to Manhattan, because it did not provide for the most efficient use of subway cars, and because it did not provide an attractive alternative to the overcrowded Queens Boulevard Line. Super express service was dismissed as the demand for local service would require two or three locals for every express, replicating the problem of the pre-1985 service pattern. Skip-stop service was dismissed for limiting the capacity of the line to 24 trains per hour, from the line's capacity of 30 trains per hour under other service patterns for express service.[40]

The NYCTA created a service plan with the goals of maintaining existing levels of reliability, having local service run at existing levels or higher than the pre-1985 level, and providing faster running times. The NYCTA proposed the reintroduction of express service, running to Manhattan between 6:30 a.m. and 10 a.m.. and to Flushing between 3:15 p.m. and 8:15 p.m.. Express service would bypass 61st Street–Woodside, allowing one express train to run for ever local, with expresses and locals both running every four minutes. The operation of expresses and locals at even frequencies was expected to aid in the even spacing of trains arriving at 33rd Street. The fast express service was expected to discourage riders boarding north of Junction Boulevard to transfer to the crowded Queens Boulevard Line.[40] The elimination of Woodside as an express stop was done in part because trains at the station would be held up by passengers transferring between the local and the express, which led to delays at the 33rd Street merge, negating the time savings.[41][42] On July 28, 1989, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Board approved the change by a vote of 5-to-3.[43] <7> express service was restored on August 21, 1989, pushed back from July.[44][45]: 17 In September 1989, 200 riders and Republican Mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani rallied at the 61st Street station to protest the elimination of express service.[41] Express service resumed stopping at Woodside resumed on a six-week test basis on February 10, 1992 after pressure from community opposition.[46]

Second renovation

In the mid-1990s, the MTA discovered that the Queens Boulevard viaduct structure was unstable, as rocks that were used to support the tracks as ballast became loose due to poor drainage, which, in turn, affected the integrity of the concrete structure overall. <7> express service was suspended again between 61st Street–Woodside and Queensboro Plaza; temporary platforms were installed to access the express track in the four intermediate stations.[47] The work began on April 5, 1993.[48][49] When the viaduct reconstruction finished on March 31, 1997, ahead of schedule, full <7> express service was reinstated.[50] Throughout this entire period, ridership grew steadily.[51] In 1999, <7> express service was expanded from rush hours only to weekdays from 6:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. However, this expansion was cut back in 2009 due to frequent midday construction.

Extension and CBTC

The 7 Subway Extension, which travels west and south to 34th Street and 11th Avenue, near the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Hudson Yards, was delayed five times.[52] The 34th Street–Hudson Yards station, originally scheduled to open in December 2013, began serving passengers on September 13, 2015.[53] However, the overall station construction project was not completed until early September 2018.[54][55][56]

On November 16, 2010, New York City officials announced they are considering a further extension of the service across the Hudson River to the Secaucus Junction train station in New Jersey.[57] As of October 26, 2011, tentative support for the extension has been given by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg as well as New Jersey Governor Chris Christie in comments to the press.[58][59] However, in April 2013, then MTA chairman Joseph Lhota announced that the 7 train would not be extended to New Jersey due to the high costs of the project, which included constructing a subway yard and a subway tunnel in New Jersey. Instead, Lhota put his support behind Amtrak’s Gateway Tunnel project which entails a new tunnel to Manhattan for Amtrak and NJ Transit trains.[60] However, as part of a joint effort between The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the MTA and NJ Transit, this extension was considered again in February 2018.[61][62][63][64][65]

In 2008, the MTA started converting the 7 service to accommodate CBTC. Expected to cost $585.9 million, CBTC will allow two additional trains per hour as well as two additional trains for the 7 Subway Extension, providing a 7% increase in capacity.[66] (At the former southern terminal, Times Square, service on the 7 was limited to 27 trains per hour (tph) as a result of the bumper blocks there. The current southern terminal at 34th Street–Hudson Yards has tail tracks to store rush-hour trains and can increase the service frequency to 29 tph.[66]) New CBTC-compatible cars for the A Division (the R188 contract) were delivered from 2013 to 2016.[66] In October 2017, the CBTC system was activated from Main Street to 74th Street.[67]: 59–65 On November 26, 2018, following numerous delays, CBTC was activated on the remainder of the 7 route. However, the MTA also announced that several more weeks of maintenance work would be needed before the system is fully operational.[68]

Rolling stock

The 7 operates with 11-car sets; the number of cars in a single 7 train set is more than in any other New York City Subway service. These trains, however, are not the longest in the system, since a train of 11 "A" Division cars is only 565 feet (172 m) long, while a standard B Division train, which consists of ten 60-foot cars or eight 75-foot cars, is 600 feet (180 m) long.

Fleet history

The 7, throughout almost all its history, has maintained a separate fleet from the rest of the IRT, starting with the Steinway Low-Vs. The Steinways were built between 1915 and 1925 specifically for use in the Steinway Tunnel. They had special gear ratios to climb the steep grades (4.5%) in the Steinway Tunnel, something standard Interborough equipment could not do.[69]

In 1938, an order of all-new World's Fair cars was placed with the St. Louis Car Company. These cars broke from IRT "tradition" in that they did not have vestibules at each car end. In addition, because the IRT was bankrupt at the time, the cars were built as single ended cars, with train controls for the motorman on one side and door controls for the conductor on the other. These cars spent their last days on the elevated IRT Third Avenue Line in the Bronx.

Starting in 1948, R12s, R14s, R15s, were delivered to the line. On November 1, 1962, fifty R17s (6500-6549) were transferred from the Mainline IRT to the 7, allowing for ten-car operation. This was the first time that the IRT ran ten-car trains without a second conductor.[70]

In 1964, the picture window R33/36 World's Fair (WF) cars replaced the older R12s, R14s, R15s, and R17s in time for the 1964 New York World's Fair. Early in 1965, the New York City Transit Authority placed a strip map indicating all the stations and transfer points for the line in each of the line's 430 cars, helping World's Fair visitors. This innovation was not used for other services and as they shared rolling stock with each other; it was possible for cars to have the wrong strip maps.[71]

The 7 was the last service to run using "Redbird" cars, and the 7's fleet consisted entirely of R33/36 WF Redbird train cars until December 2001. In 2001, with the arrival of the R142/R142A cars, the Transit Authority announced the retirement of all Redbird cars. From January 2002 to November 2003, the Bombardier-built R62A cars, which used to operate on the 3 and 6, gradually replaced all of the R33/36 WF cars on the 7. On November 3, 2003, the last Redbird train made its final trip on this route, making all stops between Times Square and the then-named Willets Point–Shea Stadium.[72] Several Redbird cars running on this service were decorated with Mets logos and colors during the 2000 Subway Series against the New York Yankees, as the Flushing Line runs adjacent to Citi Field and the former location of Shea Stadium. Many R33 WFs remained in Corona Yard and were used primarily for work service up to early 2017.

Since 2008, all R62As on the 7 have been upgraded with LED lighted signs to distinguish between express and local trains. These signs are located on the rollsigns that are found on the side of each car. The local is a green circle around the 7 bullet while the express is a red diamond.[73] Previously, the rollsigns showed either a (7) (within a circle) or a <7> (within a diamond) with the word "Express" underneath it.

The R62As were displaced by the R188s from January 2013 to March 2018 in preparation for the automation equipment for the Flushing Line. The displaced R62As were returned to the 6 train, which had given much of its R142As for conversion to R188s.[74][75] The first train of R188 cars began operating in passenger service on November 9, 2013. By 2016, most of the communications-based train control (CBTC)-equipped R188 trainsets were on the 7, and by the end of March 2018, the last R62A trains were displaced by the R188 cars.[76][77] In addition to providing six extra 11-car trains for the 7 Subway Extension, the R188s allowed twenty R62A cars to be freed up for the rest of the IRT A Division services.

Nickname

The 7 is nicknamed the "International Express" in part because it travels through several different ethnic neighborhoods populated by immigrants, especially along Roosevelt Avenue, and in part because it was the principal subway route to the 1964-65 New York World's Fair. This name is not official, nor is the title used in day-to-day operations.[78][79]

On June 26, 1999, then-First Lady Hillary Clinton and U.S. Transportation Secretary Rodney E. Slater designated the 7 route as a National Millennium Trail, along with 15 other routes including the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Underground Railroad. The route was designated under the name "International Express".[80][81]

Route

Service pattern

The following table shows the line used by the 7 and <7>, with shaded boxes indicating the route at the specified times:[82]

| Line | From | To | Tracks | Times | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all times | rush hours, peak direction | ||||

| IRT Flushing Line | Flushing–Main Street | 33rd Street–Rawson Street | express | ||

| local | |||||

| Queensboro Plaza | 34th Street–Hudson Yards | all | |||

In addition to regular local and rush-hour express services, "Super Express" service to Manhattan is also provided after New York Mets games weeknights and weekends at Citi Field, as well as after US Open tennis matches: starting at Mets–Willets Point and operating express to Manhattan, also bypassing Junction Boulevard, Hunters Point Avenue and Vernon Boulevard–Jackson Avenue.[83]

Stations

For a more detailed station listing, see IRT Flushing Line.

Stations in blue denote stops served by Super Express game specials.

| Station service legend | |

|---|---|

| Stops all times | |

| Stops all times except late nights | |

| Stops weekdays during the day | |

| Stops rush hours in the peak direction only | |

| Station closed | |

| Time period details | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act in the indicated direction only | |

| Elevator access to mezzanine only | |

Lcl |

Exp |

Stations | Subway transfers | Connections/Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queens | ||||||

| Flushing Line | ||||||

| Flushing–Main Street | LIRR Port Washington Branch at Flushing–Main Street Q44 Select Bus Service Q48 bus to LaGuardia Airport | |||||

| Mets–Willets Point | ↑[a][84] | LIRR Port Washington Branch at Mets–Willets Point (special events only) Q48 bus to LaGuardia Airport Some rush hour trips originate or terminate at this station[b] Super Express trips to 34th Street–Hudson Yards originate and terminate at this station | ||||

| | | 111th Street | Q48 bus to LaGuardia Airport Some southbound rush hour trips originate at this station | ||||

| | | 103rd Street–Corona Plaza | |||||

| Junction Boulevard | Q72 bus to LaGuardia Airport | |||||

| | | 90th Street–Elmhurst Avenue | |||||

| | | 82nd Street–Jackson Heights | |||||

| | | 74th Street–Broadway | E |

Q47 bus to LaGuardia Airport (Marine Air Terminal only) Q53 Select Bus Service Q70 Select Bus Service to LaGuardia Airport | |||

| | | 69th Street | Q47 bus to LaGuardia Airport (Marine Air Terminal only). | ||||

| 61st Street–Woodside | LIRR City Terminal Zone at Woodside Q53 Select Bus Service Q70 Select Bus Service to LaGuardia Airport | |||||

| | | 52nd Street | |||||

| | | 46th Street–Bliss Street | |||||

| | | 40th Street–Lowery Street | |||||

| | | 33rd Street–Rawson Street | |||||

| Queensboro Plaza | N |

|||||

| Court Square | G E |

|||||

| Hunters Point Avenue | LIRR City Terminal Zone at Hunterspoint Avenue (peak hours only) | |||||

| Vernon Boulevard–Jackson Avenue | LIRR City Terminal Zone at Long Island City (peak hours only) | |||||

| Manhattan | ||||||

| Grand Central–42nd Street | 4 S |

Metro-North Railroad at Grand Central Terminal | ||||

| Fifth Avenue | B |

|||||

| Times Square–42nd Street | 1 A N S |

Port Authority Bus Terminal | ||||

| 34th Street–Hudson Yards | M34 Select Bus Service | |||||

In popular culture

- The 2000 documentary film The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey is based on the ethnic diversity of the people that ride the 7 train every day.[85]

- The 7 Line Army is a group of New York Mets fans whose name is derived from the 7 route.Colton, Chris (March 26, 2013). "860 Mets Fans Strong, Opening Day Just The Start For 'The 7 Line Army'". WCBS-TV.

- In a 1999 interview, then–Atlanta Braves pitcher John Rocker gave a scathing review of the 7 train, of New York City, and of Mets fans.[86]

Notes

References

- ^ 'Subdivision 'A' Car Assignment Effective December 23, 2023'. New York City Transit, Operations Planning. December 23, 2023.

- ^ "Subdivision 'A' Car Assignments: Cars Required December 23, 2023" (PDF). The Bulletin. 67 (2). Electric Railroaders' Association. February 2024. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "7 Subway Timetable, Effective December 17, 2023". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "mta.info - Line Colors". mta.info.

- ^ "Queensboro Tunnel Officially Opened — Subway, Started Twenty-Three Years Ago, Links Grand Central and Long Island City — Speeches Made in Station — Belmont, Shonts, and Connolly Among Those Making Addresses — $10,000,000 Outlay" (PDF). New York Times. June 23, 1915. p. 22. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Subway Extension Open - Many Use New Hunters Point Avenue Station" (PDF). New York Times. February 16, 1916. p. 22. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ a b Senate, New York (State) Legislature (January 1, 1917). Documents of the Senate of the State of New York.

- ^ "Annual report — 1916-1917" (Document). Interborough Rapid Transit Company. December 12, 2013. hdl:2027/mdp.39015016416920.

- ^ "New Subway Link" (PDF). New York Times. November 5, 1916. p. XX4. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Annual report — 1916-1917" (Document). Interborough Rapid Transit Company. December 12, 2013. hdl:2027/mdp.39015016416920.

- ^ Cunningham, Joseph; DeHart, Leonard O. (1993). A History of the New York City Subway System. J. Schmidt, R. Giglio, and K. Lang. p. 48.

- ^ "Transit Service on Corona Extension of Dual Subway System Opened to the Public" (PDF). New York Times. April 22, 1917. p. RE1. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "To Celebrate Corona Line Opening" (PDF). The New York Times. April 20, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ "First Trains to be Run on Flushing Tube Line Oct. 13: Shuttle Operation Ordered to 111th Street Station on New Extension". Newspapers.com. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 5, 1925. p. 8. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ Poor's...1925. 1925. p. 523.

- ^ "Corona Subway Extended" (PDF). New York Times. May 8, 1927. p. 26. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Annual Report. J.B. Lyon Company. 1927.

- ^ "Flushing to Celebrate" (PDF). New York Times. May 13, 1927. p. 8. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Dual Queens Celebration" (PDF). New York Times. May 15, 1927. p. 3. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Fifth Av. Station of Subway Opened" (PDF). New York Times. March 23, 1926. p. 29. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Annual Report For the Year Ended June 20, 1925. Interborough Rapid Transit Company. 1925.

- ^ "New Queens Subway Opened to Times Sq" (PDF). New York Times. March 15, 1927. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Flushing Rejoices as Subway Opens – Service by B.M.T. and I.R.T. Begins as Soon as Official Train Makes First Run – Hope of 25 Years Realized – Pageant of Transportation Led by Indian and His Pony Marks the Celebration – Hedley Talks of Fare Rise – Transit Modes Depicted" (PDF). The New York Times. January 22, 1928. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Korman, Joseph (December 29, 2016). "Line Names". www.thejoekorner.com. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ "Fast Subway Service to Fair Is Opened" (PDF). New York Times. April 25, 1939. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "First Flushing Express Train Runs Monday". New York Daily News. April 20, 1939. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "DIRECT SUBWAY RUNS TO FLUSHING, ASTORIA" (PDF). The New York Times. October 15, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (November 20, 1949). "TRANSIT PLATFORMS ON LINES IN QUEENS TO BE LENGTHENED; $3,850,000 Program Outlined for Next Year to Care for Borough's Rapid Growth NEW LINKS ARE TO BE BUILT 400 More Buses to Roll Also -- Bulk of Work to Be on Corona-Flushing Route TRANSIT PROGRAM IN QUEENS OUTLINED". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Ingalls, Leonard (August 28, 1953). "2 Subway Lines to Add Cars, Another to Speed Up Service; 3 SUBWAYS TO GET IMPROVED SERVICE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Annual Report — 1962–1963. New York City Transit Authority. 1963.

- ^ a b "TA to Show Fair Train". Long Island Star – Journal. August 31, 1963. Retrieved August 30, 2016 – via Fulton History.

- ^ a b Sparberg, Andrew J. (2014). From a Nickel to a Token: The Journey from Board of Transportation to MTA. Empire State Editions. ISBN 9780823261932.

- ^ "2 I.R.T. Expresses to Cut Flushing–Times Sq. Run" (PDF). New York Times. March 10, 1953. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ "IRT-Flushing Will Add Fourth Super-Express". Long Island Star-Journal. Fultonhistory.com. August 6, 1955. p. 13. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Linder, Bernard (December 1964). "Service Change". New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association.

- ^ "I. R. T. SERVICE REDUCED; Week-End Changes Made on West Side Local, Flushing Lines" (PDF). New York Times. April 3, 1954. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "R17s to the Flushing Line". New York Division Bulletin. 5 (6). Electric Railroaders' Association: M-8. December 1962 – via Issu.

- ^ Slagle, Alton (December 2, 1990). "More delays ahead for No. 7 line". New York Daily News. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Memorandum: Flushing Line project" (PDF). laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. New York City Office of the Mayor. May 28, 1985. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c d "#7 Flushing Line Express Service" (PDF). laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. New York City Transit Authority. May 4, 1989. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Chittum, Samme (September 25, 1989). "Riders are expressive about No. 7: Elimination of 61st St. stop blasted for creating havoc". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Lubrano, Alfred (August 23, 1989). "Take No. 7 train, if you can". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Siegel, Joel (July 29, 1989). "2 train changes get OK". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Announcing #7 Express Service. Starting Monday, August 21". New York Daily News. August 20, 1989. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Annual Report on ... Rapid Routes Schedules and Service Planning. New York City Transit Authority. 1989.

- ^ "Attention 7 Customers". New York Daily News. February 7, 1992. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Pérez-Peńa, Richard (October 9, 1995). "Along the Subway, a Feat in Concrete". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ "April 1993 Map Information". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. April 1993. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "The repairs we're making on the 7 line will take some time. Like 3-4 minutes per trip if you ride the express". New York Daily News. April 2, 1993. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "7 Express service is being restored between 61 Street/Woodside and Queensboro Plaza". New York Daily News. March 28, 1997. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (February 16, 1997). "On the No. 7 Subway Line in Queens, It's an Underground United Nations". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Emma G. Fitzsimmons (March 24, 2015). "More Delays for No. 7 Subway Line Extension". New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "New 34 St-Hudson Yards 7 Station Opens". Building for the Future. New York, New York: Metropolitan Transit Authority. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

The new station opened September 13, 2015

- ^ "MTA's 7 Line Extension Project Pushed Back Six Months". NY1. June 5, 2012. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cuozzo, Steve (June 5, 2012). "No. 7 train 6 mos. late". New York Post. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "MTA Opens Second Entrance at 34 St-Hudson Yards 7 Station". www.mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 1, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ NYC Subway Line May Continue Into N.J.

- ^ "Mayor Bloomberg wants to extend 7 line to New Jersey". ABC7 New York.

- ^ "Bloomberg". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ "MTA chief: No. 7 line won't be extended to NJ". NY Daily News. New York. April 3, 2012.

- ^ "Port Authority study will consider 7 train extension to New Jersey". Curbed NY. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "7 train extension to NJ is among long-term solutions being studied to address commuter hell | 6sqft". 6sqft. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Cross-Hudson study options include 7 line extension into NJ". am New York. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "7 Train To Secaucus Idea Resurrected". Secaucus, NJ Patch. March 1, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Proposal to extend 7 train into New Jersey revived". Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c MTA's Q&A on Capital Program 2010-2014 Archived March 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting April 2018" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Nessen, S. (November 27, 2018). "New Signals Fully Installed on 7 Line, but When Will Riders See Improvements?". Gothamist. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Sansone, Gene (2004). New York Subways. JHU Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8018-7922-1.

- ^ "R17s to the Flushing Line". New York Division Bulletin. 5 (6). Electric Railroaders' Association: M-8. December 1962 – via Issu.

- ^ Annual Report 1964–1965. New York City Transit Authority. 1965.

- ^ Luo, Michael (November 4, 2003). "Let Go, Straphangers. The Ride Is Over". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ Donohue, Pete (April 1, 2008). "On No. 7 trains, red diamond means express, a green circle for local". NY Daily News. New York. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Rubinstein, Dana (September 5, 2012). "M.T.A. to upgrade 7 line by trading old cars to Lexington Avenue". Capital New York. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ http://library.rpa.org/pdf/RPA-Moving-Forward.pdf Page 47

- ^ Mann, Ted (November 18, 2013). "MTA Tests New Subway Trains on Flushing Line". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "MTA - news - New Subway Cars Being Put to the Test". mta.info.

- ^ "The International Express: Around the World on the 7 Train". Queens Tribune. Archived from the original on January 22, 2003. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cohen, Billie (January 14, 2008). "No. 7 Train From Flushing-Main Street to Times Square". The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ "First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, U.S. Transportation Secretary Slater Announce 16 National Millennium Trails". White House Millennium Council. June 26, 1999. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "The No. 7 'International Express' Rolls Into History". Queens Courier. July 8, 1999. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ "Subway Service Guide" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ "The MTA Is Your Ride to All Yankees and Mets Home Games". www.mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "Mets-Willets Point Station: Accessibility on game days and special events only". New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See also: The #7 Train: An Immigrant Journey at IMDb

- ^ "At Full Blast Shooting outrageously from the lip, Braves closer John Rocker bangs away at his favorite targets: the Mets, their fans, their city and just about everyone in it". Vault. December 27, 1999. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|