Jazz

Template:Jazzbox Jazz is a musical art form that originated in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States around the start of the 20th century. Jazz uses blue notes, syncopation, swing, call and response, polyrhythms, and improvisation, and blends African American musical styles with Western music technique and theory.

Overview

Jazz has roots in the combination of West African and Western music traditions, including spirituals, blues and ragtime, stemming from West Africa, western Sahel, and New England's religious hymns, hillbilly music, and European military band music. After originating in African American communities near the beginning of the 20th century, jazz styles spread in the 1920s, influencing other musical styles. The origins of the word jazz are uncertain. The word is rooted in American slang, and various derivations have been suggested. For the origin and history of the word jazz, see Origin of the word jazz.

Jazz is rooted in the blues, the folk music of former enslaved Africans in the U.S. South and their descendants, which is influenced by West African cultural and musical traditions that evolved as black musicians migrated to the cities. Jazz musician Wynton Marsalis states that "Jazz is something Negroes invented...the nobility of the race put into sound ... jazz has all the elements, from the spare and penetrating to the complex and enveloping."[1]

The instruments used in marching bands and dance band music at the turn of century became the basic instruments of jazz: brass, reeds, and drums, using the Western 12-tone scale. A "...black musical spirit (involving rhythm and melody) was bursting out of the confines of European musical tradition [of the marching bands], even though the performers were using European styled instruments."[2]

Small bands of black musicians, mostly self taught, who led funeral processions in New Orleans played a seminal role in the articulation and dissemination of early jazz, traveling throughout black communities in the Deep South and to northern cities.

The postbellum network of black-established schools, as well as civic societies and widening mainstream opportunities for education, produced more formally trained African-American musicians. Lorenzo Tio and Scott Joplin were schooled in classical European musical forms. Joplin, the son of a former slave and a free-born woman of color, was largely self-taught until age 11, when he received lessons in the fundamentals of music theory. Black musicians with formal music skills helped to preserve and disseminate the essentially improvisational musical styles of jazz.

Improvisation

Jazz as a genre is often difficult to define, but improvisation is a key element of the form. Improvisation has been an essential element in African and African-American music since early forms of the music developed, and is closely related to the use of call and response in West African and African-American cultural expression.

The form of improvisation has changed over time. Early folk blues music often was based around a call and response pattern, and improvisation would factor in the lyrics, the melody, or both. In Dixieland jazz, musicians take turns playing the melody while the others improvise countermelodies. In contrast to the classical form, where performers try to play the piece exactly as the author envisioned it, the goal in jazz is often to create a new interpretation, changing the melody, harmonies, even the time signature. If classical music is the composer's medium, jazz is able to stand up for the rights of the performer too, to 'adroitly weigh the respective claims of the composer and the improviser'.[3]

By the Swing era, big bands played using arranged sheet music, but individual soloists would perform improvised solos within these compositions. In bebop, however, the focus shifted from arranging to improvisation over the form; musicians paid less attention to the composed melody, or "head," which was played at the beginning and the end of the tune's performance with improvised sections in between.

As previously noted, later styles of jazz, such as modal jazz, abandoned the strict notion of a chord progression, allowing the individual musicians to improvise more freely within the context of a given scale or mode (e.g., So What on the Miles Davis album Kind of Blue). The avant-garde and free jazz idioms permit, even call for, abandoning chords, scales, and rhythmic meters.

When a pianist, guitarist or other chord-playing instrumentalist improvises an accompaniment while a soloist is playing, it is called comping (a contraction of the word "accompanying"). "Vamping" is a mode of comping that is usually restricted to a few repeating chords or bars, as opposed to comping on the chord structure of the entire composition. Most often, vamping is used as a simple way to extend the very beginning or end of a piece, or to set up a segue.

In some modern jazz compositions where the underlying chords of the composition are particularly complex or fast moving, the composer or performer may create a set of "blowing changes," which is a simplified set of chords better suited for comping and solo improvisation.

History

1800s

African American music traditions had already been a part of mainstream popular music in the United States for generations, going back to the 19th century minstrel show tunes and the melodies of Stephen Foster. Public dance halls, clubs, and tea rooms opened in the cities. Black dances inspired by African dance moves, like the shimmy, turkey trot, buzzard lope, chicken scratch, monkey glide, and the bunny hug eventually were adopted by a white public.

The cake walk, developed by slaves as a send-up of formal dress balls, became popular. White audiences saw these dances in vaudeville shows. The popular dance music of the time were blues-ragtime styles. Tin Pan Alley composers like Irving Berlin incorporated ragtime influences into their compositions.

Buddy Bolden is generally considered to be the first bandleader to play the improvised music which became known as Jazz. His band started playing around 1895 in New Orleans parades and dances. Although no recordings remain of his music, here is a link where you can hear Jelly Roll Morton's memory of Bolden's theme song, as well as obtain references on Bolden. "Charles "Buddy" Bolden".

1910s

Ragtime

Main article: Ragtime

Rhythms brought from a musical heritage in Africa were incorporated into Cakewalks, Coon Songs and the music of "Jig Bands" which eventually evolved into Ragtime, c.1895 (timeline). The first Ragtime composition was published by Ben Harney. The music, vitalized by the opposing rhythms common to African dance, was vibrant, enthusiastic and often extemporaneous.

Notably the antecedent to Jazz, early Ragtime music was in the format of marches, waltzes and other traditional song forms but the consistent characteristic was syncopation. Syncopated notes and rhythms became so popular with the public that sheet music publishers included the word "syncopated" in advertising. In 1899, a classically trained young pianist from Missouri named Scott Joplin published the first of many Ragtime compositions that would come to shape the music of a nation.

Dixieland/New Orleans Jazz

Main article: Dixieland

A number of regional styles contributed to the development of jazz. In the New Orleans, Louisiana area an early style of jazz called "Dixieland" developed. New Orleans had long been a regional music center. In addition to the slave population, New Orleans also had North America's largest community of free people of color. The New Orleans style used more intricate rhythmic improvisation than ragtime, and incorporated "blues" style elements including "bent" and "blue" notes, and using the European instruments in novel ways.

Key figures in the development of the new style were trumpeter Buddy Bolden and his band, who arranged blues tunes for brass instruments and improvised; Freddie Keppard, a Creole who was influenced by Bolden; Joe Oliver, whose style was bluesier than Bolden's; Kid Ory, a trombonist who refined the style; and Papa Jack Laine, who led a multi-ethnic band.

Other regional styles

Meanwhile, other regional styles were developing which would influence the development of jazz.

- In 1891 in Charleston, South Carolina, Reverend Daniel J. Jenkins, an African-American minister, established the Jenkins Orphanage, which included a variety of orphanage bands. The orphanage bands were trained to perform popular and religious music, and members such as William "Cat" Anderson, Gus Aiken, and Jabbo Smith went on to play with jazz bandleaders like Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton and Count Basie.

- In the northeastern United States, a "hot" style of playing ragtime developed, characterized by rollicking rhythms, without the bluesy influence of the southern styles. The music had collective improvised solos, around a melodic structure, that ideally built to a climax, supported by a rhythm section of drums, bass, banjo or guitar. The solo piano version of the northeast style was typified by Eubie Blake. "Stride" piano playing, in which the right hand plays the melody, while the left hand provides the rhythm and bassline, was developed by James P. Johnson. Johnson influenced later pianists like Fats Waller and Willie Smith. Recordings spread the "Hot" new sound across the country. James Reese Europe was a prominent orchestra leader. Tim Brymn performed with a northeastern "hot" style.

- In Chicago in the early 1910s, saxophones vigorously "ragged" a melody over a dance band rhythm section, blending New Orleans styles and creating a new "Chicago Jazz" sound. Chicago was the breeding ground for many young, inventive players. Characterized by harmonic, inovative arrangements and a high technical ability of the players, Chicago Style Jazz significantly furthered the improvised music of its day. Contributions from dynamic players like Benny Goodman, Bud Freeman and Eddie Condon along with the creative grooves of Gene Krupa, helped to pioneer Jazz music from its infancy and inspire those who followed.

- Along the Mississippi from Memphis, Tennessee to St. Louis, Missouri, the "Father of the Blues," W.C. Handy popularized a less improvisation-based approach, in which improvisation was limited to short "fills" between phrases.

1920s

With Prohibition, the constitutional amendment that forbade the sale of alcoholic beverages, speakeasies emerged as nightlife settings, and many early jazz artists played in them. The inventions of the phonograph record and of radio helped the proliferation of jazz as well. Radio stations helped to popularize Jazz, which became associated with sophistication and decadence that helped to earn the era the nickname of the "Jazz Age." In the early 1920s, popular music was still a mixture of things: current dance songs, novelty songs, and show tunes.

Key figures of the decade

Paul Whiteman, the self-proclaimed "King of Jazz," was a popular bandleader of the 1920s who hired Bix Beiderbecke and other white jazz musicians and combined jazz with elaborate orchestrations. Whiteman commissioned Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which was debuted by Whiteman's Orchestra. Ted Lewis was another popular bandleader. Some of the other bandleaders included: Harry Reser, Leo Reisman, Abe Lyman, Nat Shilkret, George Olsen, Ben Bernie, Bob Haring, Ben Selvin, Earl Burtnett, Gus Arnheim, Rudy Vallee, Jean Goldkette, Isham Jones, Roger Wolfe Kahn, Sam Lanin, Vincent Lopez, Ben Pollack and Fred Waring.

1930s

Swing

The 1930s belonged to Swing. While the solo became more important in jazz, popular bands became larger in size. During that classic era, most of the Jazz groups were Big Bands. The Big bands such as Benny Goodman's Orchestra were highly jazz oriented, while others (such as Glenn Miller's) left less space for improvisation. Key figures in developing the big jazz band were arrangers and bandleaders Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman and Duke Ellington. Swing was also dance music, which served as its immediate connection to the people. Although it was a collective sound, swing also offered individual musicians a chance to improvise melodic, thematic solos which could at times be very complex.

Over time, social strictures regarding racial segregation began to relax, and white bandleaders began to recruit black musicians. In the mid-1930s, Benny Goodman hired pianist Teddy Wilson, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, and guitarist Charlie Christian to join small groups. During this period, swing and big band music were very popular.

The influence of Louis Armstrong can be seen in bandleaders like Cab Calloway, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and vocalists like Bing Crosby, who were influenced by Armstrong's style of improvising. The style further spread to vocalists such as Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday; later, Frank Sinatra and Sarah Vaughan, among others, would jump on the scat bandwagon.

An early 1940s style known as "jumping the blues" or jump music used small combos, up-tempo music, and blues chord progressions. Jump blues drew on boogie-woogie from the 1930s, with the rhythm section playing "eight to the bar," (eight beats per measure instead of four). Big Joe Turner became a boogie-woogie star in the 1940s, and then in the 1950s was an early rock and roll musician. (Also see saxophonist Louis Jordan).

The mid 1990's saw a revival of Swing music fueled by the retro trends in dance. Once again young couples across America and Europe jitter-bugged to the swing'n sounds of Big Band music, often played by much smaller ensembles.

Kansas City Jazz

Main article: Kansas City Jazz

Kansas City Jazz in the 1930s marked the transition from big bands to the bebop influence of the 1940s. During the Depression and Prohibition eras, the Kansas City Jazz scene thrived as a mecca for the modern sounds of late 1920s and 30s. Characterized by soulful and bluesy stylings of Big Band and small ensemble Swing, arrangements often showcased highly energetic solos played to "speakeasy" audiences. Alto sax pioneer Charlie Parker hailed from Kansas City.Tom Pendergast encouraged the development of night clubs featuring musical improvisation. In 1936, the Kansas city era waned when producer John H. Hammond began sending Kansas City acts to New York City.

European Jazz

Outside of the United States the beginnings of a distinctly European jazz started emerging. At first this came mostly in France with the Quintette du Hot Club de France being among the first non-US bands of significance to jazz history. The playing of Django Reinhardt in particular would be important to the rise of gypsy jazz, which is one of the earliest genres to start outside the US.

Gypsy Jazz

Originated by Belgian guitarist Django Reinhardt, Gypsy Jazz is an unlikely mix of 1930s American swing, French dance hall "musette" and the folk strains of Eastern Europe. Also known as Jazz Manouche, it has a languid, seductive feel characterized by quirky cadences and driving rhythms. The main instruments are steel stringed guitar (particularly those of the Selmer Maccaferri line), violin, and upright bass. Solos pass from one player to another as the other guitars assume the rhythm. While primarily a nostalgic style set in European bars and small venues, Gypsy Jazz is appreciated world wide, and continues to thrive and grow in the music of artists such as Biréli Lagrène.

1940s

Bebop

In the mid-1940s with bebop performers such as saxophonist Charlie "Yardbird" Parker, pianist Bud Powell and trumpeter John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie helped to shift jazz from danceable pop music to more challenging "musician's music." Differing greatly from Swing, Bebop divorced itself early-on from dance music, establishing itself as art form but severing its potential commercial value. Other bop musicians included pianist Thelonious Monk, drummer Kenny "Klook-Mop" Clarke, trumpeters Clifford Brown and Fats Navarro, saxophonists Wardell Gray and Sonny Stitt, bassist Ray Brown, and drummer Max Roach, and vocalist Betty Carter.

The beboppers borrowed from the innovations of key earlier musicians – in particular, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and Art Tatum – and carried their ideas several steps further, introducing new forms of chromaticism and dissonance into jazz. Where many earlier styles of jazz improvisation kept close to the basic key and melodic line of the piece, bebop soloists engaged in a more abstracted form of chord-based improvisation. This often involved the use of "passing" (i.e. additional) chords, "substitute" chords, and altered chords which stepped outside of the basic key of the piece. Notes usually thought of as temporary dissonances in earlier jazz were used by the boppers as key melody notes – for instance, the flattened fifth (or augmented fourth) of the scale. The style of drumming shifted too, from the earlier four-to-the-bar bass-drum pulse to a more elusive and explosive style where the ride cymbal was used to keep time while the snares and bass drum were used for unpredictable accents.

These divergences from the jazz mainstream of the time initially met with a divided, sometimes hostile response among fans and fellow musicians. (Louis Armstrong, for instance, condemned bebop as "Chinese music.") But it was not long before bebop's influence was felt throughout jazz: older big-band leaders like Woody Herman (extensively) and Benny Goodman (briefly) experimented with the style, for instance. By the 1950s bebop had become an accepted part of the jazz vocabulary, and it has gradually over the years come to form the bedrock of modern jazz practice. While contemporary jazz musicians will study jazz from the 1920s and 1930s, they rarely attempt to duplicate those styles exactly (unless they are playing in a repertory band or trad jazz outfit); but all young jazz musicians are expected to learn bebop repertoire and style thoroughly.

1950s

Free jazz and avant-garde jazz

Main articles: Free jazz, Avant-garde jazz, European free jazz

Free jazz and avant-garde jazz, are two partially overlapping subgenres that, while rooted in bebop, typically use less compositional material and allow performers more latitude. Free jazz uses implied or loose harmony and tempo, which was deemed controversial when this approach was first developed.

Early performances of these styles go back as early as the late 40s and early 50s: Lennie Tristano's Intuition and Digression (1949) and Descent into the Maelstrom (1953) are often credited as anticipations of the later free jazz movement, though they seem not to have had a direct influence on it. The first major stirrings of what free jazz came in the 1950s, with the early work of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. In the 1960s, performers included John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, Makanda Ken McIntyre, Pharoah Sanders, Sam Rivers, Leroy Jenkins, Don Pullen, Dewey Redman and others. Peter Brötzmann, Ken Vandermark,Chefa Alonso, William Parker, Derek Bailey and Evan Parker are leading contemporary free jazz musicians, and musicians such as Coleman, Taylor and Sanders continue to play in this style. Keith Jarrett has been prominent in defending free jazz from criticism by traditionalists in recent years.

Vocalese

The art of composing a lyric and singing it in the same manner as the recorded instrumental solos. Coined by Jazz critic Leonard Feather, Vocalese reached its highest point from 1957-62. Performers may solo or sing in ensemble, supported by small group or orchestra. Bop in nature, Vocalese rarely ventured into other Jazz styles and never brought commercial success to its performers until recent years. Among those known for writing and performing vocalese lyric are Eddie Jefferson and Jon Hendricks.

Mainstream

After the end of the Big Band era, as these large ensembles broke into smaller groups, Swing music continued to be played. Some of Swing's finest players could be heard at their best in jam sessions of the 1950s where chordal improvisation now would take significance over melodic embellishment. Re-emerging as a loose Jazz style in the late '70s and '80s, Mainstream Jazz picked up influences from Cool jazz, Classical jazz and Hard bop. The terms Modern Mainstream or Post-bop are used for almost any Jazz style that cannot be closely associated with historical styles of Jazz music.

Cool Jazz

Evolving directly from Bop in the late 1940s and 1950s, Cool jazz's smoothed out mixture of Bop and Swing tones were again harmonic and dynamics were now softened. The ensemble arrangement had regained importance. Cool became nationwide by the end of the 1950s, with significant contributions from East Coast musicians and composers.

Hard Bop

An extension of Bebop that was somewhat interrupted by the Cool sounds of West Coast Jazz, Hard Bop melodies tend to be more "soulful" than Bebop, borrowing at times from Rhythm & Blues and even Gospel themes. The rhythm section is sophisticated and more diverse than the Bop of the 1940s. Pianist Horace Silver is known for his Hard Bop innovations.

1960s

Latin jazz

Main article: Latin jazz

Latin jazz has two main varieties: Afro-Cuban and Brazilian jazz. Afro-Cuban jazz was played in the U.S. directly after the bebop period, while Brazilian jazz became more popular in the 1960s and 1970s.

Afro-Cuban jazz began as a movement in the mid-'50s. Notable bebop musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Taylor started Afro-Cuban bands at that time. Gillespie's work was mostly with big bands of this genre. The music was influenced by such Cuban and Puerto Rican musicians as Xavier Cugat, Tito Puente, Mario Bauza, Chano Pozo, and much later, Arturo Sandoval.

Brazilian jazz is synonymous with bossa nova, a Brazilian popular style which is derived from samba with influences from jazz as well as other 20th-century classical and popular music. Bossa is generally moderately paced, played around 120 beats per minute with straight, rather than swing, eighth notes, and difficult polyrhythms. A blend of West Coast Cool, European classical harmonies and seductive Brazilian samba rhythms, Bossa Nova or more correctly "Brazilian Jazz," reached the United States in 1962. The subtle but hypnotic acoustic guitar rhythms accent simple melodies sung in either (or both) Portuguese or English. Pioneered by Brazilians' Joao Gilberto and Antonio Carlos Jobim, this alternative to the 60's Hard Bop and Free Jazz styles, gained popular exposure by West Coast players like guitarist Charlie Byrd & saxophonist Stan Getz.

The best-known bossa nova compositions have become jazz standards. The related term jazz-samba essentially describes an adaptation of bossa nova compositions to the jazz idiom by American performers such as Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd, and usually played at 120 beats per minute or faster. Samba itself is actually not jazz but, being derived from older Afro-Brazilian music, it shares some common characteristics.

Jazz fusion

Main article: Jazz fusion

In the late 1960s, the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was developed. Although jazz purists protested the blend of jazz and rock, some of jazz' significant innovators crossed over from the contemporary hardbop scene into fusion. Jazz fusion music often uses mixed meters, odd time signatures, syncopation, and complex chords and harmonies, and fusion includes a number of electric instruments, such as the electric guitar, electric bass, electric piano, and later, in the 1980s, synthesizer keyboards.

Notable performers of the late 1960s and 1970s jazz and fusion scene included Miles Davis, keyboardists Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock, drummer Tony Williams,guitarists Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin, Frank Zappa, Al Di Meola, jazz violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, Sun Ra, Narada Michael Walden, Wayne Shorter, and bassist-composer Jaco Pastorius.

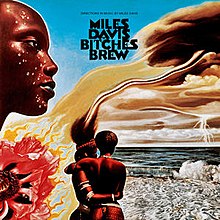

Miles Davis recorded the fusion albums In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew in 1968 and 1969. Chick Corea performed and recorded with his Return to Forever band. Ex- Miles Davis drummer Tony Williams had a band called Lifetime with Allan Holdsworth and Larry Young among others. Herbie Hancock had a funk-infused band called Headhunters band. Guitarist Larry Coryell had a band called the Eleventh House, and John McLaughlin played with a band called the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Josef Zawinul and Wayne Shorter joined forces to launch Weather Report which was the longest lasting Fusion Group and perhaps the most successful. UK band Soft Machine influenced the development of fusion in the UK.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, jazz fusion gradually turned into a lighter commercial form called pop fusion or "smooth jazz" (see paragraph below). Although pop fusion and smooth jazz were commercially successful and garnered significant radio airplay, this lighter form of fusion moved away from the style's original innovations. In the 1990s and 2000s, some fusion bands and performers such as Tribal Tech continued to develop and innovate within the genre.

Modal

Main article: Modal jazz

As smaller ensemble soloists became increasingly hungry for new improvisational directives, some players sought to venture beyond Western adaptation of major and minor scales. Drawing from medieval church modes, which used altered intervals between common tones, players found new inspiration. Soloists could now free themselves from the restrictions of dominant keys and shift the tonal centers to form new harmonics within their playing. This became especially useful with pianists and guitarists, as well as trumpet and sax players. Pianist Bill Evans is noted for his Modal approach.

Soul Jazz

Derived from hard bop, soul jazz was one of the most popular jazz styles of the 1960s, in terms of record sales. Improvising to chord progressions as with Bop, the soloist strives to create an exciting performance. The ensemble of musicians concentrate on a rhythmic "groove" centered around a strong bassline. Horace Silver had a large influence on the soul jazz style, with his songs that used funky and often Gospel-based piano vamps. Soul jazz ensembles usually gave a prominent role to the Hammond organ, and some groups, such as 1960s organ trios, were centered around the Hammond's sound.

1970s

The stylistic diversity of jazz has shown no sign of diminishing, absorbing influences from such disparate sources as world music, avant garde classical music, and a range of rock and pop musics.

Beginning in the 1970s with such artists as Keith Jarrett, Paul Bley, the Pat Metheny Group, Jan Garbarek, Ralph Towner, and Eberhard Weber, the ECM record label established a new chamber-music aesthetic, featuring mainly acoustic instruments, and incorporating elements of world music and folk music. This is sometimes referred to as "European" or "Nordic" jazz, despite some of the leading players being American.

1980s

In the 1980s, the jazz community shrunk dramatically and split. A mainly older audience retained an interest in traditional and "straight-ahead" jazz styles. Wynton Marsalis strove to create music within what he believed was the tradition, creating extensions of small and large forms initially pioneered by such artists as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Marsalis's work has influenced a wide range of musicians who have been dubbed the "Young Lions"; but it also attracted much criticism from musicians, critics and fans who found his definition of jazz too narrow, or who found his own recreations of earlier styles unconvincing.

Smooth jazz

In the 1980s, drumming became much louder and more active in jazz music. The tones of saxophones were rougher and the bass lines were more invasive. However, when jazz reached the 1990s this harsh type of music was replaced by a refined and quiet style. This style was referred to as “smooth jazz,” “cool jazz,” "contemporary jazz," or "c-jazz" for short. Some think these names are ambiguous because this so-called “smooth jazz” or “cool jazz” was no smoother than the ballads during the swing era, and it was also totally different than the “cool jazz” of the 1950s. When this music was played, instead of the improvised solos being adventuresome they were actually very stylized. For instance, the saxophone improvisations by Kenny G were considered "light fusion." His music became popular because it was basically background music with a beat meaning that people could ignore it just as well as they could listen to it. Some musicians gave this music the name "fuzak" (cf. muzak) because it was a soft, pleasant fusion of jazz and rock. By the late 1990s smooth jazz became very popular and was receiving a lot of radio exposure. Some of the most famous saxophonists of this style were Grover Washington, Jr., Kenny G and Najee and of course they had many imitators. Kenny G’s sales alone reached the millions from 1986 to 1995. Some musicians thought of jazz as just a decorative type of music instead of being substantial. However, Kenny G’s music and smooth jazz in general defined a large segment of jazz during the 1980s and 1990s. Not only is smooth jazz played on the radio and in jazz clubs, it is also played in airports, banks, offices, auditoriums and arenas (Gridley).

Gridley, Mark C. Concise Guide to Jazz: Fourth Edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education. 2004.

Acid Jazz and Nu Jazz

Styles as acid jazz which contains elements of 1970s disco, acid swing which combines 1940s style big-band sounds with faster, more aggressive rock-influenced drums and electric guitar, and nu jazz which combines elements of jazz and modern forms of electronic dance music.

Exponents of the "acid jazz" style which was initially UK-based included the Brand New Heavies, Jamiroquai, James Taylor Quartet, Young Disciples, Incognito and Corduroy. This was a natural outgrowth of the Rare Groove scene in the UK that had begun as an alternative to the prevalent Acid House parties of the 1980s. Halfway between the driving beat of house music and the Soul Jazz and Funk related sounds of Rare Grove was Acid Jazz. In the United States, acid jazz groups included the Groove Collective, Soulive, and Solsonics. In a more pop or smooth jazz context, jazz enjoyed a resurgence in the 1980s with such bands as Pigbag, Matt Bianco and Curiosity Killed the Cat achieving chart hits in Britain. Sade Adu became the definitive voice of smooth jazz. Improvisation is also largely ignored giving argument whether the term "Jazz" can truly apply.

Funk-based improvisation

Jean-Paul Bourelly and M-Base argue that rhythm is the key for further progress in the music; they believe that the rhythmic innovations of James Brown and other Funk pioneers can provide an effective rhythmic base for spontaneous composition.

These musicians playing over a funk groove and extend the rhythmic ideas in a way analogous to what had been done with harmony in previous decades, an approach M-Base calls Rhythmic Harmony.

Jazz rap

The late 80s saw a development of a fusion between jazz and hip-hop, called Jazz rap. Though some claim the proto-hip hop, jazzy poet Gil Scott-Heron the beginning of jazz rap, the genre arose in 1988 with the release of the debut singles by Gang Starr ("Words I Manifest," which samples Charlie Parker) and Stetsasonic ("Talkin' All That Jazz," which samples Lonnie Liston Smith). One year later, Gang Starr's debut LP, No More Mr. Nice Guy and their work on the soundtrack to Mo' Better Blues, and De La Soul's debut 3 Feet High and Rising have proven remarkably influential in the genre's development. De La Soul's cohorts in the Native Tongues Posse also released important jazzy albums, including the Jungle Brothers' debut Straight Out the Jungle (1988, 1988 in music) and A Tribe Called Quest's debut, People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990, 1990 in music). Guru continued the jazz rap trend with the critically acclaimed Jazzmatazz series beginning in 1993, in which modern day jazz musicians were brought into the studio.

1990s

Electronica

With the rise in popularity of various forms of electronic music during the late 1980s and 1990s, some artists have attempted a fusion of jazz with more of the experimental leanings of electronica (particularly IDM and Drum and bass) with various degrees of success. This has been variously dubbed "future jazz," "jazz-house," "nu jazz," or "Junglebop." It is often not considered to be jazz because although it is influenced by jazz, improvisation is largely absent.

The more experimental and improvisational end of the spectrum includes Scandinavian artists such as pianist Bugge Wesseltoft, trumpeter Nils Petter Molvær (both of whom began their careers on the ECM record label), the trio Wibutee, and Django Bates, all of whom have gained respect as instrumentalists in more traditional jazz circles.

The Cinematic Orchestra from the UK and Julien Lourau from France have also received praise in this area. Toward the more pop or pure dance music end of the spectrum of nu jazz are such proponents as St Germain and Jazzanova, who incorporate some live jazz playing with more metronomic house beats. Aphex Twin, Björk, Amon Tobin and Portishead are also notable as avant-garde electronica artists.

2000s

In the 2000s, "jazz" hit the pop charts and blended with contemporary Urban music through the work of neo-soul artists like Norah Jones, Jill Scott, India.Arie, Jamie Cullum, Erykah Badu, Amy Winehouse and Diana Krall and the jazz advocacy of performers who are also music educators (such as Jools Holland, Courtney Pine and Peter Cincotti). A debate has arisen as to whether the music of these performers can be called jazz or not (see below). Also pop singer Christina Aguilera recorded a jazz-based album titled Back to Basics and released it in 2006.

Debates over definition of "jazz"

As the term "jazz" has long been used for a wide variety of styles, a comprehensive definition including all varieties is elusive. While some enthusiasts of certain types of jazz have argued for narrower definitions which exclude many other types of music also commonly known as jazz, jazz musicians themselves are often reluctant to define the music they play. Duke Ellington summed it up by saying, "It's all music." Some critics have even stated that Duke Ellington's music was not in fact jazz, as by its very definition, according to them, jazz cannot be orchestrated.

There have long been debates in the jazz community over the boundaries or definition of “jazz.” In the mid-1930s, New Orleans jazz lovers criticized the "innovations" of the swing era as being contrary to the collective improvisation they saw as essential to "true" jazz. From the 1940s and 1960s, traditional jazz enthusiasts and Hard Bop criticized each other, often arguing that the other style was somehow not "real" jazz. Although alteration or transformation of jazz by new influences has been initially criticized as “radical” or a “debasement,” Andrew Gilbert argues that jazz has the “ability to absorb and transform influences” from diverse musical styles[4].

Commercially-oriented or popular music-influenced forms of jazz have long been criticized. Traditional jazz enthusiasts have dismissed the 1970s jazz fusion era as a period of commercial debasement. However, according to Bruce Johnson, jazz music has always had a "tension between jazz as a commercial music and an art form" [5].

Gilbert notes that as the notion of a canon of traditional jazz is developing, the “achievements of the past” may be become “...privileged over the idiosyncratic creativity...” and innovation of current artists. Village Voice jazz critic Gary Giddins argues that as the creation and dissemination of jazz is becoming increasingly institutionalized and dominated by major entertainment firms, jazz is facing a "...perilous future of respectability and disinterested acceptance." David Ake warns that the creation of “norms” in jazz and the establishment of a “jazz tradition” may exclude or sideline other newer, avant-garde forms of jazz[5].

One way to get around the definitional problems is to define the term “jazz” more broadly. According to Krin Gabbard “jazz is a construct” or category that, while artificial, still is useful to designate “a number of musics with enough in common part of a coherent tradition”. Travis Jackson also defines jazz in a broader way by stating that it is music that includes qualities such as “ 'swinging', improvising, group interaction, developing an 'individual voice', and being 'open' to different musical possibilities”[5].

Where to draw the boundaries of "jazz" is the subject of debate among music critics, scholars, and fans. A debate the musicians themselves very rarely bother to enter.

For example:

- Music that is a mixture of jazz and pop music, such as the recent albums of Jamie Cullum, is sometimes called "jazz."

- James Blunt and Joss Stone have been called "jazz" performers by radio DJ's, and record label promoters.

- Jazz festivals are increasingly programming a wide range of genres, including world beat music, folk, electronica, and hip-hop. This trend may lead to the perception that all of the performers at a festival are jazz artists – including artists from non-jazz genres.

See also

Template:Sample box start Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end Template:Sample box end

- List of jazz musicians

- List of jazz album [1]

- American Jazz Museum

- Cool (aesthetic)

- European free jazz

- Jazz poetry

- Jazz standard

- Jazzpar Prize

- Swing (genre)

- Thirty-two-bar form

- List of jazz pieces

- Music of the United States

Sources

- Burns, Ken & Geoffrey C. Ward. Jazz - A History of America's Music. Alfred A. Knopf, NY USA. 2000. or: The Jazz Film Project, Inc.

- Porter, Eric. What is this thing called Jazz? African American Musicians as Artists, Critics and Activists. University of California Press, Ltd. London, England. 2002.

- Szwed, John F. Jazz 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Jazz.

- The History of Jazz. Thomson-Gale Books.

- Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904-1930. Oxford University Press, Inc.

References

- ^ http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1077/is_n1_v46/ai_9019534

- ^ "North by South, from Charleston to Harlem," a project of the National Endowment for the Humanities

- ^ Gary Giddins, Visions of Jazz: The First Century (Oxford Universoty Press, 1998) p.70

- ^ In "Jazz Inc." by Andrew Gilbert, Metro Times, December 23 1998

- ^ a b c In Review of The Cambridge Companion to Jazz by Peter Elsdon, FZMw (Frankfurt Journal of Musicology) No. 6, 2003