Royal Navy

|

| His Majesty's Naval Service of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

|

| History and future |

| Ships |

| Personnel |

| Auxiliary services |

The Royal Navy of the United Kingdom is the oldest of the British armed services (and is therefore the Senior Service). From the early 18th century to the middle of the 20th century, it was the largest and most powerful navy in the world, playing a key part in establishing the British Empire as the dominant power of the 19th and early 20th centuries. In World War II, the Royal Navy operated almost 900 ships. During the Cold War, it was transformed into a primarily anti-submarine force, hunting for Soviet submarines, mostly active in the GIUK gap. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, its role for the 21st century has returned to focus on global expeditionary operations.

The Royal Navy is the second-largest navy in NATO in terms of the combined displacement of its fleet.[1] There are currently 91 commissioned ships in the Royal Navy, including aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, mine counter-measures and patrol vessels. There are also the support vessels of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. The Royal Navy's ability to project power globally is considered second only to the United States Navy.[2][3]

The Royal Navy is a constituent component of the Naval Service, which also comprises the Royal Marines, Royal Fleet Auxiliary, Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Marines Reserve. The Naval Service had 38,710 regular personnel as of November 2006.

Role

The role of the Royal Navy (RN) is to protect British interests at home and abroad, executing the foreign and defence policies of Her Majesty's Government through the exercise of military effect, diplomatic activities and other activities in support of these objectives. The RN is also a key element of the UK contribution to NATO, with a number of assets allocated to NATO tasks at any time. These objectives are delivered via a number of core capabilities:

- Maintenance of the UK Nuclear Deterrent through a policy of Continuous at Sea Deterrence.

- Provision of two medium scale maritime task groups with organic air assets.

- Delivery of the UK Commando force.

- Contribution of assets to Joint Force Harrier.

- Contribution of assets to the Joint Helicopter Command.

- Maintenance of standing patrol commitments.

- Provision of Mine Counter Measures capability to UK and allied commitments.

- Provision of Hydrographic and meteorological services deployable worldwide.

- Protection of the UK and EU's Exclusive Economic Zone.

Command, Control and Organisation

The Royal Navy is established under the Royal Prerogative, hence members of the Navy (unlike the British Army and Royal Air Force) have never been required to take the oath of allegiance to the Sovereign. The head of the Royal Navy is the Lord High Admiral, a position which has been held by the Sovereign since 1964 (the Sovereign is the overall head of the Armed Forces).

The professional head of the service is the First Sea Lord, who is a member of the Defence Council and of the Admiralty Board, which undertakes the management as delegated by the Defence Council. The Navy Board, a sub-committee of the Admiralty Board, is responsible for the running of the Naval Service. These are all based in Ministry of Defence Main Building in London, where the First Sea Lord is supported by the Naval Staff Department.

Full command of all deployable fleet units, including the Royal Marines and the Fleet Auxiliary, is delegated to Commander-in-Chief Fleet (CINCFLEET), with a Command Headquarters at HMS Excellent in Portsmouth and an Operational Headquarters at Northwood, Middlesex, co-located with the Permanent Joint Headquarters and a NATO Regional Command, Allied Maritime Component Command Northwood. CINCFLEET is also Commander AMCCN.

CINC is supported by:

- Second Sea Lord, based in HMS Excellent, Principal Personnel Officer for the Naval Service. Also Rear Admiral Fleet Air Arm.

- Deputy CINC, based in HMS Excellent, who commands the HQ.

- Commander Operations, based at Northwood, responsible for operational command of RN assets. Also Rear Admiral Submarines and Commander Submarine Allied Forces North (NATO).

- Commander UK Maritime Forces, the deployable Force Commander responsible for the Maritime Battle Staffs; UK Task Group, UK Amphibious Task Group, UK Maritime Component Command.

- Commander UK Amphibious Force / Commandant General Royal Marines.

The three Naval Bases - Portsmouth, Clyde and Devonport - each host a Flotilla Command under a Commodore, or in the case of Faslane a Captain, responsible for the provision of Operational Capability using the ships and submarines within the flotilla. 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines is similarly commanded by a Brigadier and based in Plymouth.

The purpose of CINCFLEET is to provide ships and submarines and commando forces at readiness to conduct military and diplomatic tasks as required by the UK government, including the recruitment and training of personnel.

Significant numbers of naval personnel are employed within the Ministry of Defence, Defence Logistics Organisation, Defence Procurement Agency and on exchange with the Army and Royal Air Force. Small numbers are also on exchange within other government departments.

In earlier times the office of Lord High Admiral was delegated to a naval officer. The office later came to be frequently put into commission, during which time the Royal Navy was run by a board headed by the First Lord of the Admiralty. In 1964 the functions of the Admiralty were transferred to the Secretary of State for Defence and the Defence Council of the United Kingdom. Since then, the historic title of Lord High Admiral has been restored to the Sovereign.

As of January 2007, the following persons were in office:

- Lord High Admiral: Queen Elizabeth II.

- First Sea Lord: Admiral Sir Jonathon Band

- Commander-in-Chief Fleet: Admiral Sir James Burnell-Nugent

History of the Commanders-in-Chief

Historically, the Royal Navy has usually been split into several commands, each with a Commander-in-Chief, e.g. Commander-in-Chief Plymouth, Commander-in-Chief China Station, etc. There now remain only two Commanders-in-Chief, Commander-in-Chief Fleet and Commander-in-Chief Naval Home Command.

In 1971, with the withdrawal from Singapore, the Far East and Western fleets of the Royal Navy were unified under the Commander-in-Chief Fleet (CINCFLEET), initially based in HMS Warrior, a land base in Northwood, Middlesex. This continued the trend of shore-basing the home naval command that had started in 1960 when the Home Fleet command was transferred ashore. The majority of the staff have transferred to a new facility in HMS Excellent.

The Commander-in-Chief Naval Home Command (CINCNAVHOME) has traditionally also been known as the Second Sea Lord (2SL) and is responsible for the shore-based establishments and manpower of the Royal Navy, and is based in Portsmouth. The Second Sea Lord and his staff were resident in Victory Building, Portsmouth Dockyard, and he formally flies his flag aboard HMS Victory.

In 2006 the staffs of CINCFLEET and 2SL merged, with the majority of 2SL's staff joining the CINCFLEET staff in Excellent.

Titles and naming

Of the Royal Navy

The British Royal Navy is commonly referred to as the "Royal Navy" both in the United Kingdom and other countries. Navies of Commonwealth of Nations countries where the British monarch is also head of state also include their national name e.g. Royal Australian Navy. Some navies of other monarchies, such as the Koninklijke Marine (Royal Netherlands Navy) and Kungliga Flottan (Royal Swedish Navy), are also called "Royal Navy" in their own language.

Of ships

Royal Navy ships in commission are prefixed with Her Majesty's Ship (His Majesty's Ship), abbreviated to HMS, e.g., HMS Ark Royal. Submarines are styled HM Submarine, similarly HMS. Names are allocated to ships and submarines by a naming committee within the MOD and given by class, with the names of ships within a class often being thematic (e.g.. the Type 23 class are named after British Dukes) or traditional (e.g., the Invincible class all carry the names of famous historic aircraft carriers). Names are frequently re-used offering a new ship the rich heritage, battle honours and traditions of her predecessors.

As well as a name each ship, and submarine, of the Royal Navy and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary is given a pennant number which in part denotes its role.

History

It has been suggested that this article be merged into History of the Royal Navy. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2007. |

(all headings after 1603 and the Union of the Crowns apply to the United Kingdom)

The Royal Navy has historically played a central role in the defence and wars of England, Great Britain and later the United Kingdom. As Britain is an island, invasion requires an enemy to cross the sea; in bellicose times Britain is reasonably safe from invasion only with naval superiority over all possible combinations of enemies. Moreover, a large navy was vital in maintaining the security of supply and communication with the Empire.

England - Saxon navy (c. 800–1066)

England's first navy was established in the 9th century by Alfred the Great but, despite inflicting a significant defeat on the Vikings in the Wantsum Channel at Plucks Gutter near to Stourmouth, Kent, it fell into disrepair. It was revived by King Athelstan and at the time of his victory at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, the English navy had a strength of approximately 400 ships. When the Norman invasion was imminent, King Harold had trusted to his navy to prevent William the Conqueror's invasion fleet from crossing the Channel. However, not long before the invasion the fleet was damaged in a storm and driven into harbour, and the Normans were able to cross unopposed and defeat Harold at the Battle of Hastings.

England - Norman and pre-Tudor Medieval

The Norman kings created a naval force in 1155, or adapted a force which already existed, with ships provided by the Cinque Ports alliance. The Normans are believed to have established the post of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

During the Hundred Years' War, the French fleet was initially stronger than the English fleet, but was almost completely destroyed at the Battle of Sluys in 1340. Much later the English navy suffered disastrous defeats off La Rochelle in 1372 and 1419 to Franco - Castilian fleets, and English ports were ravaged by fleets commanded by Jean de Vienne and Fernando Sánchez de Tovar. However, the French monarchs from 1380 forgot the strategic importance of naval power, and in failing to allocate sufficient resources to their navy, let what had been gained at sea slip back into English hands.

King John had a fleet of 500 sails. In the mid-fourteenth century Edward III's navy had some 712 ships. There then followed a period of decline.

England - The Tudors and the Royal Navy

see also: Henry VIII

The first reformation and major expansion of the Navy Royal, as it was then known, occurred in the 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII, whose ships Henri Grâce a Dieu ("Great Harry") and Mary Rose engaged the French navy in the battle of the Solent in 1545. By the time of Henry's death in 1547 his fleet had grown to 58 vessels.

In 1588 the Spanish Empire, at the time Europe's superpower and the leading naval power of the 16th century, threatened England with invasion and the Spanish Armada set sail to enforce Spain's dominance over the English Channel and transport troops from the Spanish Netherlands to England. The Spanish plan failed due to maladministration, logistical errors, English harrying, blocking actions by the Dutch, and bad weather. However, the bungled Drake-Norris Expedition of 1589 saw the tide of war turn against the Royal Navy. Under the reign of Elizabeth I England raided Spain's ports and Spanish ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean, but suffered a series of defeats to a reformed Spanish navy.

1692–1707

A permanent Naval Service did not exist until the mid 17th century, when the Fleet Royal was taken under Parliamentary control following the defeat of Charles I in the English Civil War. This second reformation of the navy was carried out under 'General-at-Sea' (equivalent to Admiral) Robert Blake during Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth. (Unlike the Royal Navy, the land forces are descended from a variety of different sources, including both royalist and Parliamentary forces.)

After defeats in the second and third Anglo-Dutch wars the Royal Navy gradually developed into the strongest navy in the world. From 1692 the Dutch navy was placed under the command of the Royal Navy's admirals (though not incorporated into it) by order of William III following the Glorious Revolution.

1707–1812 The Royal Navy becomes the British navy

In 1707, the Kingdom of England united with the Kingdom of Scotland to create the Kingdom of Great Britain. The Royal Navy absorbed the Royal Scots Navy per the Acts of Union. The early 18th century saw the Royal Navy with more ships than other navies, although it suffered severe financial problems throughout this period, and was heavily in debt, which affected its operations and administration. During the 18th century the government developed improved means of financing the Royal Navy through bonds. With improved cash flow, the Royal Navy began to develop the strategic ability to counter the movements of other countries' naval forces by the means of blockades, supported by more resources, the gradual development of superior naval tactics and strategy, and consistently high morale. This eventually led to almost uncontested power over the world's oceans from 1805 to 1914, when it came to be said that "Britannia ruled the waves".

The Napoleonic Wars and Trafalgar

The Napoleonic Wars saw the Royal Navy reach a peak of efficiency, dominating the navies of all Britain's adversaries. The height of the Navy's achievements came on 21 October 1805 at the Battle of Trafalgar where a numerically smaller but more experienced British fleet under the command of Admiral Lord Nelson decisively defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet.

The victory at Trafalgar consolidated the United Kingdom's advantage over other European maritime powers. By concentrating its military resources in the navy it could both defend itself and project its power across the oceans as well as threaten rivals' ocean trading routes. Britain therefore needed to maintain only a relatively small, highly mobile, professional army that sailed to where it was needed, and was supported by the navy with bombardment, movement, supplies and reinforcement. The Navy could cut off enemies' sea-borne supplies, as with Napoleon's army in Egypt. Other major European powers had to divide their resources between large navies, large armies, and fortifications to defend their land frontiers. The domination of the sea therefore allowed Britain to rapidly build its empire after the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) and throughout the 19th century, giving it enormous military, political and commercial advantages.

Unlike the navy of pre-revolutionary France, the highest commands of the Royal Navy were open to all within its ranks showing talent. This greatly increased the number of talented men available, although there was always a bias towards the upper class. The French revolution's anti-aristocratic purges caused the loss of most of the French navy's experienced commanders, increasing the Royal Navy's advantage over France.

During wartime, ships were often manned by means of Impressment, where experienced seamen could be required to move from merchant ships to naval vessels, and (from 1795) by the Quota System, where each county was required to supply a certain number of volunteers.

The conditions of service for ordinary seamen, while poor by modern standards, were better than many other kinds of work at the time. However, inflation during the late 18th century eroded the real value of seamen's pay, while at the same time, the war caused an increase in pay for merchant ships. Naval pay also often ran years in arrears, and shore leave decreased as ships needed to spend less time in port with better provisioning and health care, and copper bottoms (which delayed fouling). Discontent over these issues eventually resulted in serious mutinies in 1797 when the crews of the Spithead and Nore fleets refused to obey their officers and some captains were sent ashore. This resulted in the short-lived "Floating Republic" which at Spithead was quelled by promising improvements in conditions, but at the Nore resulted in the hanging of 29 mutineers. It is worth noting that neither of the mutinies included flogging or impressment in their list of grievances, and in fact, the mutineers continued the practice of flogging themselves to preserve discipline.

Napoleon acted to counter Britain's maritime supremacy and economic power, closing European ports to British trade. He also authorised many privateers, operating from French territories in the West Indies, placing great pressure on British mercantile shipping in the western hemisphere. The Royal Navy was too hard-pressed in European waters to release significant forces to combat the privateers, and its large ships of the line were not very effective at seeking out and running down fast and manoueverable privateers which operated as widely spread single ships or small groups. The Royal Navy reacted by commissioning small warships, of traditional Bermuda design. The first three ordered from Bermudian builders, HMS Dasher, HMS Driver and HMS Hunter, were sloops of 200 tons, armed with twelve 24-pounder guns. A great many more ships of this type were ordered, or bought from trade, primarily for use as couriers. The most notable was HMS Pickle, the former Bermudian merchantman that carried news of victory back from Trafalgar.

In the years following the battle of Trafalgar there was increasing tension at sea between the Britain and the United States. American traders took advantage of their country's neutrality to trade with both the French-controlled parts of Europe and Britain. Both France and Britain tried to prevent each other's trade, but only the Royal Navy was in a position to enforce a blockade. Another irritant was the suspected presence of British deserters aboard US merchant and naval vessels. Royal Navy ships often attempted to recover these deserters. In one notorious instance in 1807, otherwise known as the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, HMS Leopard fired on USS Chesapeake causing significant casualties before boarding and seizing suspected British deserters.

American War of 1812–1815

In 1812, while the Napoleonic wars continued, the United States declared war on the United Kingdom and invaded Canada. At sea, the American War of 1812 was characterised by single-ship actions between small ships, and disruption of merchant shipping. The Royal Navy struggled to build as many ships as it could, generally sacrificing on the size and armament of vessels, and struggled harder to find adequate personnel, trained or barely-trained to crew them. Royal Naval vessels were often under-manned, without sufficient men to fire a full broadside. Many of the men crewing Royal Naval vessels were rated only as landsmen, and many of those rated as seamen were impressed (conscripted), with resultingly poor morale. The US Navy couldn't begin to equal the Royal Navy in number of vessels, and had concentrated in building a handful of better-designed frigates. These were larger, heavier and better-armed (both in terms of number of guns, and in the range to which the guns could fire) than their British counterparts, and were handled well by larger volunteer crews (where the Royal Navy was hindered by a relative shortage of trained seamen, the US Navy was not large enough to make full use of the large number of American merchant seamen put out of work, even before the war, by the Embargo Act). As a result, a number of British ships were defeated and, mid-way through the war, the Admiralty issued the order not to engage American frigates individually. There were also significant losses of merchant shipping to American privateers, a total of 1,300 vessels;[4][5] however, the Royal Navy, operating from its new base and dockyard, off the US Atlantic Seaboard in Bermuda, gradually reinforced the blockade of the American coast, virtually halting all trade by sea, capturing many merchant ships, and forcing the US navy frigates to stay in harbour or risk being captured. Despite successful American claims for damage having been pressed in British courts against British privateers several years before, the War was probably the last occasion on which the Royal Navy made considerable reliance on privateers to boost Britain's maritime power. In Bermuda, privateering had thrived until the build-up of the regular Royal Naval establishment, which began in 1795, reduced the Admiralty's reliance on privateers in the Western Atlantic. During the American War of 1812, however, Bermudian privateers captured 298 enemy ships (the total captures by all British naval and privateering vessels between the Great Lakes and the West Indies was 1,593 vessels).

By this time, the Royal Navy had begun building a naval base and dockyard in Bermuda, which replaced Newfoundland as the winter location of the Admiralty. The Royal Navy had begun development after American independence had deprived it of bases on most of the North American seaboard. In time Bermuda became the headquarters for Royal Naval operations in the waters of southern North America and the West Indies. During the War of 1812 the Royal Navy's blockade of the US Atlantic ports was coordinated from Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The blockade kept most of the American navy trapped in port. The Royal Navy also occupied coastal islands, encouraging American slaves to defect. Units of Royal Marines were raised from these freed slaves. After British victory in the Peninsular War, part of Wellington's Light Division was released for service in North America. This 2,500-man force, composed of detachments from the 4, 21, 44, and 85 Regiments with some elements of artillery and sappers and commanded by Major-General Ross, arrived in Bermuda in 1814 aboard a fleet composed of the 74-gun HMS Royal Oak, three frigates, three sloops and ten other vessels. The combined force was to launch raids on the coastlines of Maryland and Virginia, with the aim of drawing US forces away from the Canadian border. In response to American actions at Lake Erie, however, Sir George Prevost requested a punitive expedition which would 'deter the enemy from a repetition of such outrages'. The British force arrived at the Patuxent on 17 August and landed the soldiers within 36 miles of Washington DC. Led by Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, the British force drove the US government out of Washington, DC. Ross shied from the idea of burning the City, but Cockburn and others set it alight. Buildings burned included the US Capitol and the US President's Mansion.

Between 1793 and 1815 the Royal Navy lost 344 vessels due to non-combat causes: 75 by foundering, 254 shipwrecked and 15 from accidental burnings or explosions. In the same period it lost 103,660 seamen: 84,440 by disease and accidents, 12,680 by shipwreck or foundering, and 6,540 by enemy action.

1815–1914

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the regular seamen of the Royal Navy saw considerable changes. Impressment and the Quota System were both abolished, leading to an all-volunteer navy. At the same time, the Admiralty introduced new regulations on punishment, banning starting (the striking of men by officers to hurry them along) and placing severe restrictions on the practice of flogging, and pay and shore leave became more regular.

During the 19th century the Royal Navy enforced a ban on the slave trade, acted to suppress piracy, and continued to map the world. To this day, Admiralty charts are maintained by the Royal Navy.

Royal Navy vessels on surveying missions carried out extensive scientific work. Charles Darwin travelled around the world on HMS Beagle, making scientific observations which led him to the theory of evolution.

During the latter half of the 19th century, ships of the Royal Navy were used for what has ironically been called 'gunboat diplomacy'. Large, heavily armed boats with shallow draught were employed in coastal areas in the far reaches of the Empire, to demonstrate Britain's power to local populations and rulers, and to intervene where the UK's perceived interests were at stake.

By the end of the 19th century the Royal Navy, despite being the largest in the world, was not as powerful as it seemed to be. It was a collection of new, powerful steam pre-Dreadnoughts such as the Royal Sovereign Class, older steam ironclad vessels, and sailing ships several decades old. First Lord of the Admiralty Jackie Fisher retired, scrapped, or placed into reserve many of the older vessels, making funds and manpower available for newer ships. He was also the main force behind the development of HMS Dreadnought, the first all-big-gun ship and one of the most influential ships in naval history. At one stroke, this ship rendered all other battleships then existing obsolete, and started an arms race in which Great Britain had a lead over all others. Fisher was also a proponent of submarines, and bought a few based on John Holland's design from Vickers.

Admiral Percy Scott introduced new gunnery training programs and a central fire control station, greatly improving accuracy and ship effectiveness in battle. Wireless telegraphs were introduced onto flagships, and the Parsons Turbine and experiments with oil as fuel led to greatly increased range and speed.

1914–1945

During the two World Wars the Royal Navy played a vital role in keeping the United Kingdom supplied with food, arms and raw materials and in defeating the German campaigns of unrestricted submarine warfare in the first and second battles of the Atlantic.

During the First World War the majority of the Royal Navy's strength was deployed at home in the Grand Fleet in an effort to blockade Germany and to draw the Hochseeflotte (the German "High Seas Fleet") in to an engagement where a decisive victory could be gained. Although there was no decisive battle, the Royal Navy and the Kaiserliche Marine fought many engagements: the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the Battle of Coronel, the Battle of the Falkland Islands, the Battle of Dogger Bank and the Battle of Jutland. This last was the best-known battle. The Royal Navy suffered heavier losses, but succeeded in its strategic goal: the Hocheseeflotte never again put to sea.

The Royal Navy was also heavily committed in the Dardanelles Campaign against the Ottoman Empire. During the war, the Navy contributed the Royal Naval Division to the land forces of the New Army.

In the inter-war period the Royal Navy was stripped of much of its power. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 imposed limits on individual ship tonnage and gun calibre, as well as total tonnage of the navy. The treaty, together with the deplorable financial conditions during the immediate post-war period and the Great Depression, forced the Admiralty to scrap all capital ships from the Great War with a gun calibre under 15 inches and to cancel plans for new construction. Three planned units of the G3 Hood class of battlecruiser and the N3 class of 16-inch battlecruisers and 18-inch battleships were cancelled. Also under the treaty, three "large light cruisers"—Glorious, Courageous and Furious—were converted to aircraft carriers. New additions to the fleet were therefore minimal during the 1920s, the only major new vessels being two Nelson class battleships and fifteen County and York class heavy cruisers.

The London Naval Treaty of 1930 deferred new capital ship construction until 1937 and reiterated construction limits on cruisers, destroyers and submarines. As international tensions increased in the mid-1930s the Second London Naval Treaty of 1935 failed to halt the development of a naval arms race and by 1938 treaty limits were effectively ignored. The re-armament of the Royal Navy was well under way by this point however, with the 1936 King George V class of 1936, limited to 35,000 tons and 14-inch armament, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, and the Illustrious class carriers, the Town and Crown Colony classes of light cruiser and the Tribal class destroyers. In addition to new construction, several existing old battleships, battlecruisers and heavy cruisers were reconstructed, and anti-aircraft weaponry reinforced.

As a result, the Royal Navy entered the Second World War as a heterogeneous force of World War I veterans, inter-war ships limited by close adherence to treaty restrictions and later unrestricted designs. It remained a powerful force, though smaller and relatively older than it was during World War I.

During the early phases of World War II, the Royal Navy provided critical, if depressing, cover during British evacuations from Dunkirk and Crete. In the latter operation Admiral Cunningham ran great risks to extract the Army, and saved many men to fight another day. The prestige of the Navy suffered severe blows when the battlecruiser Hood was sunk by the German battleship Bismarck, and the Repulse and Prince of Wales were sunk by Japanese air attack. The Bismarck was sunk a few days later, though public pride in the Royal Navy was severely damaged as a result of the loss of mighty Hood.

The Royal Navy was also vital in guarding the sea lanes that enabled British forces to fight in remote parts of the world such as North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Far East. From 1942, responsibility for the protection of Atlantic convoys was divided between the various allied navies: the Royal Navy being responsible for much of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. Suppression of the U-boat threat was an essential requirement for the invasion of northern Europe: the necessary armies could not otherwise be transported and resupplied. During this period the Royal Navy acquired many relatively cheap and quickly-built escort vessels.

Naval supremacy was vital to the amphibious operations carried out, such as the invasions of Northwest Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. During the war however, it became clear that aircraft carriers were the new capital ship of naval warfare, and that Britain's former naval superiority in terms of battleships had become irrelevant. Britain was an early innovator in aircraft carrier design, in place of the now obsolete and vulnerable battleship, although the Royal Navy was now dwarfed by its ally, the United States Navy.

The successful invasion of Europe reduced the European role of the navy to escorting convoys and providing fire support for troops near the coast as at Walcheren, during the battle of the Scheldt. Despite opposition from the U.S. naval chief, Admiral Ernest King, the Royal Navy sent a large task force to the Pacific (British Pacific Fleet). This required the use of wholly different techniques, requiring a substantial fleet support train, resupply at sea and an emphasis on naval air power and defence. It remains the largest foreign deployment of the Royal Navy.

Deployment

At the start of World War II, Britain's global commitments were reflected in the Navy's deployment. Its first task remained the protection of trade, since Britain was heavily dependent upon imports of food and raw materials, and the global Empire was also interdependent.

The navy's assets were allocated between various Fleets and Stations[6]

| Home Fleet | home waters, ie, north-east Atlantic, North Sea, English Channel (sub-divided into commands and sub-commands) |

| Mediterranean Fleet | Mediterranean Sea |

| South Atlantic and Africa Station | south Atlantic and South African region |

| America and West Indies Station | western north Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, eastern Pacific |

| East Indies Station | Indian Ocean (excluding South Atlantic and Africa Station, Australian waters and waters adjacent to Dutch East Indies) |

| China Station | north west Pacific and waters around Dutch East Indies |

The Cold War

After World War II, the decline of the British Empire and the economic hardships in Britain at the time forced the reduction in the size and capability of the Royal Navy. The increasingly powerful U.S. Navy took on the former role of the Royal Navy as a means of keeping peace around the world. However, the threat of the Soviet Union and British commitments throughout the world created a new role for the Navy. In the 1960s, the Royal Navy received its first nuclear weapons and was later to become responsible for the maintenance of the UK's nuclear deterrent. In the latter stages of the Cold War, the Royal Navy was reconfigured with three anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft carriers and a force of small frigates and destroyers. Its purpose was to search for and destroy Soviet submarines in the North Atlantic.

Operations since 1982

The most important operation conducted predominantly by the Royal Navy after the Second World War was the defeat in 1982 of Argentina in the Falkland Islands War. Despite losing four naval ships and other civilian and RFA ships the Royal Navy proved it was still able to fight a battle 8,345 miles (12,800 km) from Great Britain. HMS Conqueror is the only nuclear-powered submarine to have engaged an enemy ship with torpedoes, sinking the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano. The war also underlined the importance of aircraft carriers and submarines and exposed the service's late 20th century dependence on chartered merchant vessels.

The Royal Navy also took part in the Gulf War, the Kosovo conflict, the Afghanistan Campaign, and the 2003 Iraq War, the last of which saw RN warships bombard positions in support of the Al Faw Peninsula landings by Royal Marines. Also during that war, HM submarines Splendid and Turbulent launched a number of Tomahawk cruise missiles at targets in Iraq.

In August 2005 the Royal Navy rescued seven Russians stranded in a submarine off the Kamchatka peninsula. Using its Scorpio 45, a remote-controlled mini-sub, the submarine was freed from the fishing nets and cables that had held the Russian submarine for three days.

The Royal Navy has deployed a number of Naval Task Groups to the Far East including "NTG 03" in 2003, HM ships Exeter, Echo, RFAs Diligence and Grey Rover in 2004 and HMS Liverpool and RFA Grey Rover in 2005.

Composition of the Fleet since 1960

|

|

| Year[7] | Submarines | Carriers | Assault Ships | Surface Combatants | Mine Counter Measure Vessels | Patrol Ships and Craft | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | SSBN | SSN | SS & SSK | Total | CV | CV(L) | Total | Cruisers | Destroyers | Frigates | |||||

| 1960 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 145 | 6 | 55 | 84 | 202 | ||

| 1965 | 47 | 0 | 1 | 46 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 117 | 5 | 36 | 76 | 170 | ||

| 1970 | 42 | 4 | 3 | 35 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 97 | 4 | 19 | 74 | 146 | ||

| 1975 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 72 | 2 | 10 | 60 | 43 | 14 | 166 |

| 1980 | 32 | 4 | 11 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 13 | 53 | 36 | 22 | 162 |

| 1985 | 33 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 56 | 0 | 15 | 41 | 45 | 32 | 172 |

| 1990 | 31 | 4 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 49 | 0 | 14 | 35 | 41 | 34 | 160 |

| 1995 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 35 | 0 | 12 | 23 | 18 | 32 | 106 |

| 2000 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 32 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 98 |

| 2005 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 28 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 16 | 26 | 90 |

| 2006 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 25 | 0 | 8 | 17 | 16 | 22 | 82 |

The Royal Navy today

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Royal Navy was a force designed for the Cold War with a focus on blue water anti-submarine warfare. Its purpose was to search for and destroy Soviet submarines in the North Atlantic, and to operate the nuclear deterrent submarine force. However, the Falklands War proved a need for the Royal Navy to regain an expeditionary and littoral capability which, with its resources and structure at the time, would prove difficult.

UK foreign policy after the end of the Cold War has given rise to a number of operations which have required an aircraft carrier to be deployed globally such as the Adriatic, Peace Support Operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, Sierra Leone, the Persian Gulf. Destroyers and frigates have been deployed against piracy in the Malacca Straits and Horn of Africa. Consequently in the 1990s the navy began a series of projects to modernise the fleet and convert it from a North Atlantic-based anti-submarine force to an expeditionary force.[8]

Current deployments

The Royal Navy is currently deployed in many areas of the world, including a number of standing Royal Navy deployments.

Home tasks

- Fleet Flagship HMS Ark Royal

- Fleet Amphibious Flagship HMS Albion

- Fleet Rapid Reaction Units HMS Kent, HMS Lancaster

- Fishery Protection Squadron HMS Mersey, HMS Severn, HMS Tyne

Mediterranean/European tasks

- UK On Call Mine Countermeasures Force Task Group (Orion '07) HMS Atherstone, HMS Hurworth, HMS Shoreham, HMS Walney, RFA Cardigan Bay

- Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 (SNMG2) HMS Montrose

- Standing NATO Mine Counter Measures Group 1 (SNMCMG1) HMS Brocklesby

- Cyprus Squadron HMS Dasher, HMS Pursuer

- Gibraltar Squadron HMS Sabre, HMS Scimitar

North Atlantic tasks

- Atlantic Patrol Task (North) – APT(N) HMS Ocean, RFA Wave Ruler

- Survey Vessel HMS Scott

South Atlantic tasks

- Atlantic Patrol Task (South) HMS Edinburgh, RFA Gold Rover

- Falkland Islands Patrol Vessel HMS Dumbarton Castle

Middle East tasks

- Gulf Patrol Ship HMS Cornwall, RFA Sir Bedivere

- Arabian Sea and Horn of Africa HMS Richmond

- Aintree Deployment HMS Blyth, HMS Ramsey

- Gulf Ready Tanker RFA Bayleaf

- Survey Vessel HMS Enterprise

Far East tasks

- Far East Guardship HMS Monmouth

Special Forces

The Royal Navy provides the Special Boat Service (SBS), one of the three Special Forces units within the United Kingdom Special Forces group.

The SBS is a naval Special Forces unit and is an independent part of the Royal Marines. It is made up of 4 operational squadrons and an SBS Reserve (SBS(R)), and is based at Royal Marines Poole, in Poole, Dorset.

It has roles in naval special operations such as combat swimmer missions, small boat operations, amphibious raids and Maritime Counter-Terrorism. As a Special Forces unit, its role is not limited to water-borne operations. It also conducts operations on land, either as the Special Forces element of 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines, or separately.

The SBS Reserve provides individual members of the Royal Marines Reserve to serve alongside the regular SBS.

Custom and tradition

Heraldry

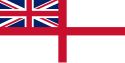

Commissioned ships and submarines wear the White Ensign at the stern whilst alongside during daylight hours and at the main-mast whilst under way. When alongside, the Union Jack (as distinct from the Union Flag, often referred to as the Union Jack) is flown from the jackstaff at the stem, and can only be flown under way either to signal a court-martial is in progress or to indicate the presence of an Admiral of the Fleet on-board (including the Lord High Admiral, the Monarch).[9]

Fleet reviews

The Fleet Review is an irregular tradition of assembling the fleet before the monarch. For example, at the most recent Review on 28 June 2005 to mark the bi-centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar, 167 ships of the RN, and 30 other nations, were present.

Service nicknames

Nicknames for the service include "The Andrew" (of uncertain origin, possibly after a zealous press ganger[10][11]) and "The Senior Service".[12][13] It has also been referred to as the "Grey Funnel Line" in joking comparison with the commercial Blue Funnel Line.

Naval salute

Originally subordinates would uncover (remove their headgear) to a superior. In a book called New Art of War, printed in 1740, it is stated that;

- When the King or Captain General is being saluted each Officer is to time his salute so as to pull off his hat when the person he salutes is almost opposite him.

Queen Victoria instituted the hand salute in the Navy to replace uncovering when she sent for certain officers and men to Osborne House to thank them for rendering help to a distressed German ship, and did not like to see men in uniform standing uncovered.[citation needed]

The personal salute with the hand is borrowed from the military salute of the Army, and there are various theories concerning its origin. There is the traditional theory that it has been the custom from time immemorial for a junior to uncover to a superior, and even today men on Captain's Defaulters remove their hats. In this theory, the naval salute is merely the first motion of removing one's head dress. It was officially introduced into the Navy in 1890, but during the First World War a large number of old retired officers were in the habit of doffing their head gear instead of saluting, this, of course, being the method to which they were accustomed.

Another theory holds that in the age of sail, hemp ropes were preserved in tar, causing the sailor's hands to become stained. It would have been a discourtesy to show the dirty palm to one's superior, therefore the naval salute differs from the military salute in that it has the palm turned down, rather than outwards.[14] The Royal Marines, with their military origin, use the military rather than the naval salute.

Affiliation

Ships will engage in a number of affiliations with cities, e.g. HMS Newcastle with Newcastle upon Tyne, elements of the other forces, e.g. HMS Illustrious with 30 Signal Regiment, schools, cadet units and charities. Every sea cadet unit in the UK has an affiliated ship, with the exception of Yeovil unit which, due to their location on RNAS Yeovilton, are affiliated with 848 Helicopter Squadron.

Naval slang

The RN has evolved a rich volume of slang, known as "Jack-speak". Nowadays the British sailor is usually "Jack" (or "Jenny") rather than the more historical "Jack Tar", which is an allusion to either the former requirement to tar long hair or the tar-stained hands of sailors. Nicknames for a British sailor, applied by others, include "Matelot" (pronounced matlow), derived from French or "Limey".[12] Royal Marines are fondly known as "Bootnecks" or often just as "Royals".[12]

Uckers and Ucker

Uckers is a four player board game similar to Ludo that is traditionally played in the Royal Navy. It is fiercely competitive and rules differ between ships and stations (and between other services). Ucker, pronounced you-ker, is a card game also played on board ships and in naval establishments. It is similar to Trumps, is highly competitive and extremely difficult to learn.

The Royal Navy in fiction

- The Napoleonic campaigns of the navy have been the subject of many novels including Patrick O'Brian's series featuring Jack Aubrey, C.S. Forester's Horatio Hornblower, Dudley Pope's Ramage and Alexander Kent's Richard Bolitho.

- Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe series though primarily involving the Peninsular War of the time, includes several novels involving Richard Sharpe at sea with the Navy.

- Alexander Kent is a pen name of Douglas Reeman who, under his birth name, has written many novels featuring the Royal Navy in the two World Wars.

- Noel Coward directed and starred in his own film In Which We Serve, which tells the story of the crew of the fictional HMS Torrin during World War II. It was intended as a propaganda film and was released in 1942. Coward starred as the ship's captain, with supporting roles from John Mills and Richard Attenborough.

- Other well known novels include Alistair MacLean's HMS Ulysses, Nicholas Monsarrat's The Cruel Sea, and C.S. Forester's The Ship, all set during World War II.

- The Royal Navy has also been the subject of an acclaimed 1970s BBC television drama series, Warship.

- The fictional spy James Bond is 'officially' a commander in the Royal Navy.

- The Royal Navy features in the blockbuster movie trilogy Pirates of the Caribbean.

Royal Navy timeline and battles

Famous sailors of the Royal Navy

Famous People who Served in the Royal Navy

- Alec Guinness, actor, served during World War II, initially as a rating but later commissioned.

- Ralph Richardson, actor, served as a Lieutenant-Commander during World War II.

- Sir Laurence Olivier, actor, served in the Fleet Air Arm during World War II, rasing to the rank of Lieutenant.

- Harry H. Corbett, actor, famous for Steptoe and Son, served in the Royal Marines during later part of World War II.

- Peter O'Toole, actor, served as a Radioman during his National Service.

- Sean Connery, actor, served in the Royal Navy during his National Service.

- Sir Ludovic Kennedy, journalist, broadcaster and author served in the Royal Navy during World War II.

- Prince Albert of York, later George VI of the United Kingdom, served as midshipman during World War I.

- William Golding, Novelist, Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, served as a Lieutenant and was present at the sinking of the Bismarck

Famous ships of the Royal Navy

For a full list, see List of Royal Navy ship names

- Mary Rose — sank in 1545 off Portsmouth

- Golden Hind — flagship of Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation and raid on Spanish shipping.

- Ark Royal — flagship of English Fleet against the Spanish Armada. As of 2005, the current Ark Royal is an Invincible-class aircraft carrier that saw action in the 2003 Iraq conflict

- Revenge — actively engaged Spanish Armada; later became the subject of a poem by Lord Tennyson detailing her heroic fight against a large Spanish force in 1591.

- Bounty — scene of the famous mutiny.

- Victory — Nelson's flagship. This ship is still officially in service and is the world's oldest commissioned warship and the flagship of the Second Sea Lord

- Beagle — carried Charles Darwin on his voyage.

- Warrior — Britain's first iron hulled, armoured battleship

- Dreadnought — first "all big-gun" battleship

- Warspite — fought at Jutland and through the Second World War

- Hood — battlecruiser destroyed by the Bismarck

- Vanguard — last battleship built for the Royal Navy & also ran aground in Portsmouth Harbour

- Dreadnought — first British nuclear-powered submarine

- Resolution — first British strategic ballistic missile submarine

- Invincible — light aircraft carrier

- Intrepid — end of the Falklands War signed aboard

- Conqueror — The first, and so far only, nuclear powered submarine to sink an enemy ship.

See also

References

- ^ "Chapter II: REGIONAL OVERVIEW AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF KEY ALLIES: Contributions of Selected NATO Allies". Allied Contributions to the Common Defense: A Report to the United States Congress by the Secretary of Defense. United States Department of Defense. March 2001. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ^ Royal Navy website

- ^ Henry Jackson Society website

- ^ Website of the American Merchant Marine at War

- ^ USN website

- ^ Royal Navy in World War 2

- ^ a b c Created from data in UK defence statistics + Conways All the World's Fighting Ships 1947–1995

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/newspapers/sunday_times/britain/article1265414.ece

- ^ Flags of the World: Use of the Union Jack at Sea

- ^ Admiralty Manual of Seamanship, 1964, HMSO.

- ^ http://www.nmm.ac.uk/server/show/conWebDoc.17840 National Maritime Museum

- ^ a b c Jackspeak, Rick Jolly, Maritime Books Dec 2000, ISBN 0-9514305-2-1

- ^ http://www.royal-navy.mod.uk/server/show/nav.3804 Naval Slang

- ^ http://www.raf.mod.uk/info/faqs_1.html#salute Royal Air Force FAQs; salutes

External links

- Official Website of the Royal Navy

- The Navy List 2006 - list of all serving officers.

- Sea Your History Website from the Royal Naval Museum - Discover detailed information about the Royal Navy in the 20th Century.

- Navy News - Royal Navy Newspaper

- UK Military News & Information Portal

- The Marine Society College of the Sea

- The service registers of Royal Naval Seamen 1873 - 1923

- Royal Navy in World War 1, Campaigns, Battles, Warship losses

- Royal Navy in World War 2, Campaigns, Battles, Warship losses

- Royal and Dominion Navies, Victoria Cross at Sea, 1940-45

- A free to use forum and information site for potential, current and ex Royal Marines