Cumans

This article possibly contains original research. (December 2012) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2012) |

The Cumans (Turkish: kuman / plural kumanlar[1] Template:Lang-hu;[2] Template:Lang-gr;[3] Template:Lang-ro, Template:Lang-pl, Template:Lang-ru, Polovtsy; Template:Lang-uk, Polovtsi; Template:Lang-bg, Czech: Plavci, Georgian: ყივჩაყი, ყიფჩაღი, German: Falones, Phalagi, Valvi, Valewen, Valani) were a Turkic[2][4][5][6] nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman-Kipchak confederation. After the Mongol invasion (1237), many sought asylum in Hungary[7] and, subsequently, Bulgaria. Other researchers state that the Cumans were welcomed to Hungary before the Mongol invasion.[8] Cumans had also settled in Bulgaria before the Mongol invasion.[citation needed]

Related to the Pecheneg,[9] they inhabited a shifting area north of the Black Sea and along the Volga River known as Cumania, where the Cuman-Kipchaks meddled in the politics of the Caucasus and Khwarezm.[10] Many eventually settled to the west of the Black Sea, influencing the politics of Kievan Rus', the Golden Horde, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Moldavia, Georgia and Wallachia. Cuman and Kipchak tribes joined politically to create the Cuman-Kipchak confederation.[11] The Cuman language is attested in some medieval documents and is the best-known of the early Turkic languages.[12] The Codex Cumanicus was a linguistic manual which was written to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cuman people.

The Cumans were nomadic warriors of the Eurasian steppe who exerted an enduring impact on the medieval Balkans. The basic instrument of Cuman political success was military force, which dominated each of the warring Balkan factions. Groups of the Cumans settled and mingled with the local population in regions of the Balkans. Arguments have been brought forward which state that the name of three successive Bulgarian dynasties (Asenids, Terterids, and Shishmanids) and the founding Wallachian dynasty (Basarabids) are of Cuman origin.[11][13] But, in the cases of the Basarab and Asenid dynasties, medieval documents refer to them as Vlach (Romanian) dynasties.[14][15][16] They played an active role in Byzantium, Hungary, and Serbia, with Cuman immigrants being integrated into each country's elite.

The Cumans were called Folban and Vallani/Valwe by Germans, Kun (Qoun) by the Hungarians, and Polovtsy/Polovec (from Old East Slavic "половъ" — yellow) by the Russians — all meaning "blond". It is difficult to know which group historians were referring to when they used the name Kipchak, as they could refer to the Cumans only, the Kipchaks only, or to both together. The two nations joined and lived together (and possibly exchanged weaponry, culture and fused languages). This confederation and their living together may have made it difficult for historians to write exclusively about either nation. Some of the clans of the Cuman-Kipchaks were the Terteroba, Burdjogli, Toksoba, Etioba/Ietioba, Kay, Itogli, Kochoba (meaning Ram Clan), Urosoba, El'Borili, Kangarogli, Andjogli, Durut, Djartan, Karabirkli, Kotan/Hotan, Kulabaogli, Olelric, Altunopa and the Olberli.

Etymology

The Cumans' name in Russian and German means "yellow", in reference to the color of the Cumans' hair.[17] The Ukrainian word Polovtsy (Пóловці) means "blond", since the old Ukrainian word polovo means "straw". Kuman means "pale yellow" in Turkic. Some authors put forward the idea that the name Polovtsy referred to "men of the field, or of the steppe" (from the Ukrainian word pole: open ground, field), not to be confused with polyane (cf. Greek polis: city). In Slavic languages the word 'polyane' literally means "open ground, field". According to O. Suleymenov polovtsy came from a word for "blue-eyed", since the Serbo-Croatian word plav means "blue":[18] the Eastern Slavic equivalent would take the regular form *polov.

History

The Cumans originally lived east of the large bend of the Yellow River in China.[19] They entered the grassland of Eastern Europe in the 11th century, from where they continued to assault the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary, and Kievan Rus'. The vast territory of the Cuman-Kipchak realm consisted of loosely connected tribal units who were the dominant military force but were never politically united by a strong central power. There was no state or empire of Cumania. Rather, different groups under independent rulers, or khans, acted on their own initiative, often meddling in the political life of the surrounding states. Cumans interacted with the Rus' principalities; with Bulgaria, Byzantium, and the Wallachian states in the Balkans; with Armenia and Georgia (see Kipchaks in Georgia) in the Caucasus; and with the Khwarezm in Central Asia, having created a powerful caste of warriors, the Mamluks and the Mamluk Sultanate. The Cumans were also active in commerce with traders from Central Asia to Venice.[20]

The Cumans first encountered the Rus' in 1055, which resulted in a peace agreement. In 1061, however, the Cumans invaded and devastated the Rus' Pereiaslav principality.[21] In 1068 at the Alta River, the Cumans defeated the armies of the three sons of Yaroslav the Wise — Iziaslav Yaroslavych, Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych, and Vsevolod Yaroslavych. After the Cuman victory, they repeatedly invaded Ukraine, devastating the land and taking captives, who became either slaves or were sold at markets in the south. The most vulnerable regions were the principalities of Pereiasla, Novhorod-Siverskyi, and Chernihiv.[21]

The Cumans initially managed to defeat the Great Prince Vladimir Monomakh of Kievan Rus in 1093 at the Battle of the Stugna River, but they were defeated later by the combined forces of Russian principalities led by Monomakh and forced out of the Rus borders to Caucasus. Many Cumans at that time resettled in Georgia where they achieved prominent positions and helped Georgians to stop the advance of Seljuk Turks. After the death of warlike Monomakh in 1125, Cumans returned to the steppe along the Rus borders.

In the Balkans, the Cumans were in contact with all of the statal entities of that time, fighting with the Kingdom of Hungary, allied with the Bulgarians and Vlachs against the Byzantine Empire, and involved in the politics of the fresh Vlach states. A notable Cuman leader in Europe, Thocomer (Toq-tämir, meaning ‘hardened steel’) was possibly the first to unite the Romanian (Vlach) states from the west and the east of the Olt River. Thocomer's son Basarab[22] ("Father king"[13] in the Cuman language) is considered the first ruler of the united and independent kingdom of Wallachia. This interpretation corresponds with the general view of the situation of Romania in the 11th century, with the natives living in collections of village communities united in small confederacies, and with powerful chiefs competing to create small kingdoms. Some of these Romanian chiefs paid tribute to the militarily dominant nomadic tribes that surrounded them.

In 1089, Ladislaus I of Hungary defeated the Cumans after they attacked the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1091, the Pechenegs, a semi-nomadic Turkic people of the prairies of southwestern Eurasia, were decisively defeated as an independent force at the Battle of Levounion by the combined forces of a Byzantine army under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and a Cuman army under Togortok and Bunaq. Attacked again in 1094 by the Cumans, many Pechenegs were again slain. The remnants of the Pechenegs fled to Hungary, as the Cumans themselves would do a few decades later: Fearing the Mongol invasion, they asked asylum from Béla IV of Hungary in 1229.

In alliance with the Bulgarians and Vlachs[23][24] during the Vlach-Bulgar Rebellion by brothers Asen and Peter of Tarnovo, the Cumans are believed to have played a significant role in the rebellion's final victory over Byzantium and the restoration of Bulgaria's independence in 1185.[25] Istvan Vassary states that without the active participation of the Cumans, the Vlakho-Bulgarian rebels could never have gained the upper hand over the Byzantines, and ultimately without the military support of the Cumans, the process of Bulgarian restoration could never have been realised.[11] The Cuman participation in the creation of the Second Bulgarian Empire in 1185 and thereafter brought about basic changes in the political and ethnic sphere of Bulgaria and the Balkans.[11] The Cumans were allies in the Bulgarian-Latin Wars with emperor Kaloyan of Bulgaria, who was descended from the Cumans.

Like most other peoples of medieval Eastern Europe, they put up resistance against the relentlessly advancing Mongols, led by Jebe and Subutai. The Mongols crossed the Caucasus mountains in pursuit of Muhammad II, the shah of Khwarazm, and met and defeated the Cumans in Subcaucasia in 1220. The Cuman khans Danylo Kobiakovych and Yurii Konchakovych died in battle, while the other Cumans, commanded by Koten, managed to get aid from the Rus’ princes.[21]

As the Mongols were approaching Russia, Khan Koten fled to the court of his son-in-law, Prince Mstislav the Bold of Galich. He warned Mstislav: "Today the Mongols have taken our land and tomorrow they will take yours." However, the Cumans were ignored for almost a year as the Rus had suffered from Cuman raids for decades. But when news reached Kiev that the Mongols were marching along the Dniester River, the Rus responded. Mstislav gathered an alliance of the Kievan Rus' princes including Mstislav III of Kiev and Prince Yuri II of Vladimir-Suzdal, who promised support with Khan Koten's Cumans. The Rus princes then began mustering their armies and going towards the rendezvous point. The army of the alliance of the Rus and Cumans numbered around 80,000. The battle took place near Kalka River (Battle of Kalka River). Due to confusion from mistakes from the Rus and Cumans, the battle was lost — the Cumans and Rus were defeated (1223). The Cumans were allied in this battle with Wallach warriors named Brodnics, led by Ploscanea.[citation needed] Brodnics territory was in the lower parts of Prut river in today Romania and Moldova. The Cumans were finally crushed in 1238.

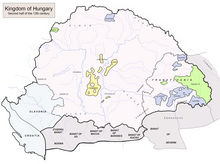

During the second Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe in 1237 the Cumans were defeated again. After the defeat some Cuman tribes followed Koten to Hungary and Bulgaria, where they became part of the local population; they were integrated into the élite and became nobles and rulers. In Hungary Cumans created two regions named Cumania (Kunság in Hungarian): Greater Cumania (Nagykunság) and Little Cumania (Kiskunság), both in the Great Hungarian Plain. The Hungarian king, in return for their military service, invited the Cumans to settle in areas of the Great Plain between the Danube and the Theiss Rivers (today's Great Cumania and Little Cumania); this region had become almost uninhabited after the Mongol raids of 1241-1242.[26] The Cumanians lived there until their settlements were destroyed during the Turkish wars (16th and 17th centuries).[27] At the beginning of the 18th century the Cumanian territories were resettled by their Hungarian-speaking descendants of the Cumans.[28] In the middle of the 18th century they got their status by becoming free farmers and no longer serfs.[8][29] Here, the Cumans maintained their autonomy, language and some ethnic customs well into the modern era. According to Pálóczi's estimation originally 70-80,000 Cumans settled in Hungary.[30] The Cumans were in every way different to the local population of Hungary — their appearance, attire and hairstyle set them apart. In Hungary, the Cumans were exempt from jurisdiction of country officials; the Cumans had their own representatives. The Cumans also participated in some of the early general assemblies of Hungary, the precursors of its parliament. At the time of Elizabeth the Cuman, queen of Hungary, gifts of precious clothes, land and other objects were given to the Cumans with the intent to ensure their support. By the 15th century, all the Cumans were permanently settled in Hungary, in villages whose structure corresponded to that of the local population, and were Christianized. The Cumans did not always ally to the Hungarian kings; they assassinated Laszlo IV. The royal and ecclesiastical authorities incorporated, rather than excluded, the Cumans. The Cumans in Hungary served as light cavalry in the royal army, as an obligation since they were granted asylum. Being very fierce and capable warriors (as noted by Istvan Vassary), the king lead them in numerous expeditions against neighbouring countries; most notably they played an important part in the battle of Rudolf of Habsburg and Ottokar II of Bohemia (1278) — King Laszlo IV and the Cumans were on Rudolf's side. Laszlo IV was particularly fond of the Cumans and abandoned Hungarian culture and dress for Cuman culture, dress and hairstyle (he spent much time with them).[31] Although they were defeated by the Mongols, the cultural heritage of the Cumans that remained in the Rus steppe (those who did not move to Hungary and Bulgaria) was transferred on to the Mongols. The Mongol élite adopted a lot of the traits, customs and language from the Cumans and Kipchaks; the Cumans, Kipchaks and Mongols finally became assimilated through intermarriage and became the Golden Horde. The Cumans, with the Turko-Mongols, adopted Islam, in the second half of the 13th and the first half of the 14th century.[21]

In 1229, they had asked for asylum from King Béla IV of Hungary, who in 1238 finally offered refuge to the remainder of the Cuman people under their leader Kuthen (Hungarians spelled his name Kötöny). Kuthen in turn vowed to convert his 40,000 families to Christianity. King Béla hoped to use the new subjects as auxiliary troops against the Mongols, who were already threatening Hungary. The king assigned parts of central Hungary to the Cuman tribes. A tense situation erupted when Mongol troops burst into Hungary. The Hungarians, frustrated by their own helplessness, took revenge on the Cumans, whom they accused of being Mongol spies. After a bloody fight, the Hungarians killed Kuthen and his bodyguards, and the remaining Cumans fled to the Balkans, pillaging and destroying many Hungarian villages in the way. After the Mongol invasion Béla IV of Hungary recalled the Cumans to Hungary to populate settlements devastated by war. The nomads subsequently settled throughout the Great Hungarian Plain. During the following centuries the Cumans in Hungary were granted rights, the extent of which depended on the prevailing political situation. Some of these rights survived until the end of the 19th century, although the Cumans had long since assimilated with Hungarians.

Istvan Vassary states that after the Mongol conquest, "A large-scale westward migration of the Cumans began. In the summer of 1237 the first wave of this Cuman exodus appeared in Bulgaria. The Cumans crossed the Danube, and this time Ivan Asen II could not tame them, as he had often been able to do earlier; the only possibility left for him was to let them march through Bulgaria in a southerly direction. They proceeded through Thrace as far as Hadrianoupolis and Didymotoichon, plundering and pillaging the towns and the countryside, just as before. The whole of Thrace became, as Akropolites put it, a ‘Scythian desert’".[32]

The pontic Cumania (Latin term for Deshti-Kipchak, not the Cumania in modern-day Romania and Moldova) ceased to exist in the middle of the 13th century, when the Great Mongol Invasion of Europe occurred. In 1223, Genghis Khan defeated the Cumans and their Russian allies at the Battle of Kalka River (in modern Ukraine). The final blow came in 1241, when the Cuman confederacy ceased to exist as a political entity, with the remaining Cuman tribes being dispersed, either becoming subjects and mixing with their Tatar-Mongol conquerors as part of what was to be known as the Nogai Horde or fleeing to the west, to the Byzantine Empire, the Second Bulgarian Empire, and the Kingdom of Hungary, where they became kings and nobles with many privileges.

Cumans had served as mercenaries in the armies of the Byzantine Empire from the end of the 11th century and were one of the most important elements of the Byzantine army until the mid-14th century. They served as horse-archers and those in the central army were collectively called Skythikoi. In 1241, the Byzantines settled 10,000 Cumans in Thrace and Anatolia where they became hellenized. A Greek-speaking Cuman even became Megas Domestikos (Commander-in-Chief of the Army) under Emperor Andronikos II.[33]

The Cumans who remained scattered in the prairie of what is now southwest Russia joined the Golden Horde khanate, and their descendants became assimilated with local Tatar populations.

The Cumans who remained east and south of the Carpathian Mountains established a county named Cumania, in an area consisting parts of Moldavia and Walachia. The Hungarian kings claimed supremacy on the territory of Cumania, among the nine titles of the Hungarian kings of the Árpád and Anjou dynasties were rex Cumaniae.

The Cuman influence in Wallachia and Moldavia was very strong, according to some historians who claim that the earliest Wallachian rulers bore supposedly Cuman names[34] (e.g., Tihomir and Bassarab). This hypothesis is though disputed (Tihomir sounding like a Slavic given name), while the toponymy of the most densely populated regions of Romanian settlement shows strong evidence of Cuman placenames.[34] In lack of convincing archaeological evidence of a Cuman civilisation, it appears the Cumans were a minority in the local population, but they made up part of the ruling élite in Wallachia. As in the case of Bulgaria, they were assimilated by the majority, the present-day Romanians.

Basarab I, son of the Wallachian prince Thocomerius of Wallachia obtained independence from Hungary at the beginning of the 14th century. The name Basarab is considered by some authors as being of Cuman origin, and meaning "Father King".

It is generally believed by Bulgarian historians that the Bulgarian mediaеval dynasties Asen, Shishman and Terter were Cumanian.

The Caucasian mummies found in China a while ago could have been Cumans, as it is stated that the Cumans originally came from eastern China before migrating to Europe.[11]

Codex Cumanicus

The Codex Cumanicus was a linguistic manual for the Cuman language of the Middle Ages, designed to help Catholic missionaries communicate with the Cumans. It is currently housed in the Library of St. Mark, in Venice (Cod. Mar. Lat. DXLIX). Some parts from the Codex's Pater Noster are shown below:

Atamız kim köktesiñ. Alğışlı bolsun seniñ atıñ, kelsin seniñ xanlığıñ, bolsun seniñ tilemekiñ – neçikkim kökte, alay [da] yerde. Kündeki ötmegimizni bizge bugün bergil. Dağı yazuqlarımıznı bizge boşatqıl – neçik biz boşatırbiz bizge yaman etkenlerge. Dağı yekniñ sınamaqına bizni quurmağıl. Basa barça yamandan bizni qutxarğıl. Amen!

In English, the text is: Our Father which art in heaven. Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins as we forgive those who have done us evil. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.

In Modern Turkish, the text is:

Atamız sen göktesin. Alkışlı olsun senin adın, gelsin senin hanlığın, olsun senin dileğin– nasıl ki gökte, ve yerde. Gündelik ekmeğimizi bize bugün ver. Ve de yazıklarımızdan (suçlarımızdan) bizi bağışla– nasıl biz bağışlarız bize yaman (kötülük) edenleri. Ve de şeytanın sınamasından bizi koru. Tüm yamandan (kötülükten) bizi kurtar. Amin!

Cuman prayer:

| Cuman Language | Modern Turkish | English |

|---|---|---|

|

Bizim atamız kim-szing kökte |

Bizim atamız ki sensin gökte |

Our father who is in the sky |

Their language, known from a 13th-century trilingual Cumanian-Latin-Persian dictionary, was a form of Turkish and was, until the 14th century, a lingua franca over much of the Eurasian steppes.[35][36]

Culture

Despite their historical status, the ethnic origins of the Cumanians are uncertain, although their anthropological characteristics suggests that their geographical origin might be in Inner-Asia, South-Siberia.[8][37][38] Robert de Clari described Cumans as nomadic warriors, who did not use houses or farm, but rather lived in tents, and ate milk, cheese and meat. The horses had a sack for feeding attached to the bridle, and in a day and a night they can ride seven days of walking (Mansio), they go on campaign without any baggage, and when they return they take everything they can carry; they wear sheepskin and were armed with composite bows and arrows. They pray to the first animal they see in the morning.[39][40] The Cumans, like the Bulgars, were known to drink blood from their horse (they would cut a vein) when they ran out of water and were far from an available source. Another interesting feature of the Cumans was their elaborate masks which they used in battle — they were shaped like and worn over the face.

A typical feature were mustaches. The traditional Cuman costume consisted of trousers and a caftan, each fastened by a belt. The men shaved the top of their head, while the rest of the hair was plaited into several braids. The Cumans commonly wore pointed hats.[31]

The main activity of the Cumans was animal husbandry. They raised horses, sheep, goats, camels, and cattle. In summer they moved north with their herds; in winter, south. Some of the Cumans led a semi-settled life and took part in trading and farming. They mainly sold and exported animals, mostly horses, and animal products. The Cumans also played the role of middlemen in the trade between Byzantium and the East, which passed through the Cuman-controlled ports of Surozh, Oziv, and Saksyn. Several land routes between Europe and the Near East ran through Cuman territories: the Zaloznyi, the Solianyi, and the Varangian. Cuman towns — Sharukan, Suhrov, and Balin — appeared in the Donets River Basin; they were inhabited, however, by other peoples besides the Cumans. Rock figures called stone babas, which are found throughout southern Ukraine, were closely connected with the Cuman religious cult of shamanism. The Cumans tolerated all religions, and Islam and Christianity spread quickly among them. As they were close to the Kyivan Rus’ principalities, the Cuman khans and important families began to Slavicize their names, for example, Yaroslav Tomzakovych, Hlib Tyriievych, Yurii Konchakovych, and Danylo Kobiakovych. Ukrainian princely families were often connected by marriage with Cuman khans; this lessened wars and conflicts. Sometimes the princes and khans waged joint campaigns; for example, in 1221 they attacked the trading town of Sudak on the Black Sea, which was held by the Seljuk Turks and which interfered with Rus’-Cuman trade.[21]

Niketas Choniates, while describing a battle in the vicinity of Beroe in the late 12th century, gave an interesting description of the nomadic battle techniques of the Cumans:

"They [i.e., the Cumans] fought in their habitual manner, learnt from their fathers. They would attack, shoot their arrows and begin to fight with spears. Before long they would turn their attack into flight and induce their enemy to pursue them. Then they would show their faces instead of their backs, like birds cutting through the air, and would fight face to face with their assailants and struggle even more bravely. This they would do several times, and when they gained the upper hand over the Romans [Byzantines], they would stop turning back again. Then they would draw their swords, release an appalling roar, and fall upon the Romans quicker than a thought. They would seize and massacre those who fought bravely and those who behaved cowardly alike."[41]

Religion

It is alleged that the Cumans practiced Tengrinism. Their belief system comprised animistic and shamanistic elements; they celebrated the cult of ancestors and provided the dead with objects whose lavishness paralleled the recipient's social rank. The Cumans buried the elite with their horses (like the Bulgars). Cuman divination practices used animals, especially the wolf and dog. Cumans had shamans who communicated with the spirit world — they were consulted for questions of outcomes.[31] The Cumans in Christian territories were baptised in 1227 by Róbert Archbishop of Esztergom in a mass baptism in Moldavia on the orders of Bortz Khan, who swore allegiance to King Andrew II of Hungary.[42]

Polovetian leaders (Khan) (Ruthenian chronicles)

- Iskal or Eskel (possibly a self-name of a bolgharic tribe (Nushibi)) who were mentioned by Ahmad ibn Fadlan after visiting Volga region in 921-922. They also were mentioned by Abu Saʿīd Gardēzī in his Zayn al-Akhbār. According to Bernhard Karlgren, Eskels became the Hungarian people Székelys. Yury Zuev thought that Iskal who is mentioned in the Laurentian Codex about the first military encounter of Cumans against the Ruthenians on February 2, 1061, is personification of a tribal name.

- Sharukan, grand father of Konchak. Another Polovetian khan who was victorious against the Ruthenian army of Yaroslavichi at the Alta river (Battle of the Alta River). According to the Novgorod First Chronicle Sharukan was taken as prisoner by Svyatoslav II of Kiev in 1068, while no such information is provided in the Laurentian Codex. In May of 1107 along with Bonyak, Sharukan raided couple of Ruthenian cities (Pereyaslav and Lubny), however already in August of the same year the collective Ruthenian army led by Svyatoslav carried out a devastating defeat to the Cuman Horde forcing Sharukan to flee.

- Bonyak,[43] Polovetian khan who actively was involved in civil conflicts of Ruthenia. He had a brother Taz who perished at the battle on the Sula River in 1107. Bonyak was last mentioned in 1167 when he was defeated by Oleg of Siveria. Bonyak was a leader of Cuman tribe Burchevichi that resided in steppes of the East Ukraine between modern cities of Zaporizhia and Donetsk.

- Tugorkan (1028-1096) was mentioned in essays of the Byzantine Empress Anna Komnene along with his compatriot Bonyak. He perished with his son at the battle on the Trubizh River against the Ruthenian army.

- Syrchan, a son of Sharukan. He was a leader of Cuman tribe that lived on the right banks of Siversky Donets. Chronicles mentioned that Syrchan sent out a singer Orev to Georgia after his brother Atrak. Syrchan was mentioned in the poem of Apollon Maykov (1821-1897) "Eshman".

- Atrak, a son of Sharukan and a brother of Syrchan. In 1111 along with his brother withdrew to Lower Don region after loosing a battle against the Ruthenians. There Atrak's horde joined the local Alans. In 1117 his army sacked Sarkel forcing the local Pechenegs and Torkils to flee to Ruthenia. Around the same time Atrak invaded the Northern Caucasus where he entered into conflict with local Circasians pushing them beyond the Kuban River. The conflict was settled by a Georgian King David IV of Georgia who offered a military service to Atrak against Seljuks in 1118. David also married the daughter of Atrak Gurandukht. After withdrawal of Atrak away from the Don region, the Alan's duchy in East Ukraine was liquidated in 1116-17. Atrak returned after the death of Vladimir Monomakh in 1125.

Legacy

While the Cumans were gradually absorbed into eastern European populations, their trace can still be found in placenames as widespread as the city of Kumanovo in the northeastern Republic of Macedonia; a Slavic village named Kumanichevo in the Kostur (Kastoria) district of Greece, which was changed to Lithia after Greece obtained this territory in the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest; Comăneşti in Romania; a village of Kumane in Serbia; Comana in Dobrogea (also Romania); the small village of Kumanite in Bulgaria; and Debrecen in Hungary.

As the Mongols pushed westward and devastated their state, most of the Cumans fled to the Bulgarian Empire as they were major military allies. The Bulgarian Tsar Ivan-Asen II (who was descended from Cumans)[citation needed] settled them in the southern parts of the country, bordering the Latin Empire and the Thessallonikan Despotate.[citation needed] Those territories are in present-day Turkish Europe, Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia.[citation needed]

The Cumans also settled in Hungary and had their own self-government in a territory that bore their name, Kunság, that survived until the 19th century. Two regions — Little Cumania and Greater Cumania — exist in Hungary. The name of the Cumans (Kun) is preserved in county names such as Bács-Kiskun and Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok and town names such as Kiskunhalas, Kunszentmiklós. The municipality of Kuman in the Fier District, Fier County, southwestern Albania is a legacy of the Cumans.

The Cumans were organized into four tribes in Hungary: Kolbasz/Olas in upper Cumania around Karcag and the other three in lower Cumania.

Unfortunately, the Cuman language disappeared from Hungary in the 17th or 18th century (1770?), possibly following the Turkish occupation. Their 19th-century biographer, Gyárfás István, in 1870 was of the opinion that they originally spoke Hungarian, together with the Iazyges population. Despite this mistake, he has the best overview on the subject[citation needed] concerning details of material used.

In addition, toponyms of Cuman language origin can be found in some Romanian counties of Vaslui and Galaţi, including the names of both counties.

When some of the Cumans moved to Hungary, they brought with them their Komondor dogs, which have become one of the national dogs of Hungary.

In the countries where the Cumans were assimilated, family surnames derived from the words for "Cuman" (such as coman or kun, "kuman") are not uncommon. Traces of the Cumans are the Bulgarian surnames Kunev or Kumanov (feminine Kuneva, Kumanova), its Macedonian variants Kunevski, Kumanovski (feminine Kumanovska), and the widespread Hungarian surname Kun. The names "Coman" in Romania and its derivatives, however, do not appear to have any connection to the medieval Cumans, as it was unrecorded until very recent times and the places with the highest frequency of such names has not produced any archaeological evidence of Cuman settlement.[44]

In the Hungarian village of Csengele, on the borders of what is still called Kiskunsag, Little Cumania, an archeological excavation in 1975 revealed the ruins of a medieval church with 38 burials. Several burials had all the characteristics of a Cumanian group: richly jeweled, non-Hungarian, and definitely Cumanian-type costumes; the 12-spiked mace as a weapon; bone girdles; and associated pig bones.[45] In view of the cultural objects and the historical data, the archeologists concluded that the burials were indeed Cumanian and mid-13th century; hence some of the early settlers in Hungary were from that ethnic group. In 1999 the grave of a high-status Cumanian from the same period was discovered about 50 m from the church of Csengele; this was the first anthropologically authenticated grave of a Cumanian chieftain in Hungary,[26] and the contents are consistent with the ethnic identity of the excavated remains from the church burials. A separated area of the chieftain grave contained a complete skeleton of a horse.[8]

A genetic study was done on Cuman burials within Hungary and it was determined that they had substantially more western Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages.[46] In a 2005 study by Erika Bogacsi-Szabo et al. of the mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) of the Cuman nomad population that migrated into the Carpathian basin during the 13th century, six haplogroups were revealed.

"One of these haplogroups belongs to the M lineage (haplogroup D) and is characteristic of Eastern Asia, but this is the second most frequent haplogroup in southern Siberia too. All the other haplogroups (H, V, U, U3, and JT) are West Eurasian, belonging to the N macrohaplogroup. Out of the eleven remains, four samples belonged to haplogroup H, two to haplogroup U, two to haplogroup V, and one each to the JT, U3, and D haplogroups. In comparison to the Cumans, modern Hungarian samples represent 15 haplogroups. All but one is a West Eurasian haplogroup [the remaining one is East Asian (haplogroup F)], but all belong to the N lineage. Four haplogroups (H, V, U*, JT), present in the ancient samples, can also be found in the modern Hungarians, but only for haplogroups H and V were identical haplotypes found. Haplogroups U3 and D occur exclusively in the ancient group, and 11 haplogroups (HV, U4, U5, K, J, J1a, T, T1, T2, W, and F) occur only in the modern Hungarian population. Haplogroup frequency in the modern Hungarian population is similar to other European populations, although haplogroup F is almost absent in continental Europe; therefore the presence of this haplogroup in the modern Hungarian population can reflect some past contribution."[47] "The results suggested that the Cumanians, as seen in the excavation at Csengele, were far from genetic homogeneity. Nevertheless, the grave artifacts are typical of the Cumanian steppe culture; and five of the six skeletons that were complete enough for anthropometric analysis appeared Asian rather than European (Horváth 1978, 2001), including two from the mitochondrial haplogroup H, which is typically European. It is interesting that the only skeleton for which anthropological examination indicated a partly European ancestry was that of the chieftain, whose haplotype is most frequently found in the Balkans."[47]

The study concluded that the mitochondrial motifs of Cumans from Csengele show the genetic admixtures with other populations rather than the ultimate genetic origins of the founders of Cuman culture. So the maternal lineages of a large part of the group would reflect the maternal lineage of those populations that had geographic connection with the Cumans during their migrations. Nevertheless, the Asian mitochondrial haplotype in Cu26 may still reflect the origins of the Cumans of Csengele. Considering genetic distances, Cumans ( of Csengele) are nearest to the Finnish, Komi and Turkish populations.[48]

The Cumans appear in Rus culture in The Tale of Igor's Campaign and are the Rus' military enemies in Alexander Borodin's opera Prince Igor, which features a set of Polovtsian Dances.

The name Cuman is the name of several villages in Turkey, such as Kumanlar, including the Black Sea region.

Gallery

-

"Baba" 11th century, Luhansk

-

"Baba" 11th century, Luhansk

-

"Baba" 11th century, Luhansk

-

"Baba" 11th century, Luhansk

-

"Baba" 11th century, Luhansk

-

Cuman, 12th century Hermitage Museum

-

"Baba" at the Open Air Museum, Prelesne

-

Chormukhinsk Madonna, Luhansk

-

Cuman Stone statue "baba"

-

Cuman Stone statue "baba"

-

Ladislas IV of Hungary, 14th century

-

Ladislaus IV of Hungary (the Cuman)

-

Elizabeth the Cuman mediaeval seal

-

Kunkereszt ("Cuman cross") in Belez, periphery of Magyarcsanád, Hungary

-

Cuman stone statues "babas"

-

Cuman prairie art, as exhibited in Dnipropetrovsk

-

Cumans in Hungary

-

Cuman burial mound in Hungary

Famous or notable Cumans, or people of Cuman descent, in history

This article possibly contains original research. (December 2012) |

- Qutb-ud-din Aibak - founder of the Delhi sultanate

- Khan Boniak (Maniak), chieftain during time of Sharukan. He was called "the Mangy" by Russians. He led the invasions on Kievan Rus'. In 1096 Boniak attacked Kiev, plundered the Kiev Monastery of the Caves, and burned down the prince's palace in Berestovo

- Khan Köten (or Sutoiovych), Mstyslav Mstyslavych's father-in-law, fought in the war against the Mongols (allied with the Russians); led 40000 "huts" (families) to Hungary, to escape from the Mongols, where he was later assassinated. The Cumans then emigrated to the Second Bulgarian Empire. Some of the Cumans were later called back to Hungary. He was possibly the most notable of Cumans (together with Baibars). Allegedly descended from the Cuman Terteroba clan. He ws the person who rallied the Rus (allied with the Cumans) against the Mongols

- Khan Konchak (Konchek, Kumcheg - meaning 'trousers'), a chieftain, daughter married Igor's son Prince Vladimir of Putivl; was involved in wars and raids with the Russians (Prince Igor), along the Ros River, where the Cumans attacked towns belonging to the Olgovichi (the ruling dynasty of Chernigov)

- Atraga, Dagestan, he led a tribe of 40000 to Georgia (could have been either a Kipchak or Cuman,or mixed, its uncertain)

- Sultan Baibars ("white bigcat-Siberian Tiger"/"leopard" in Turkic), Mamluke Empire,founder of the Bahri dynasty; he was one of the commanders of the forces which inflicted a devastating defeat on the Seventh Crusade of King Louis IX of France and he led the vanguard of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260; he was possibly the most famous Cuman (but cf. Vlad the Impaler, infraa)

- Qutuz, Sultan of Egypt (Mamluke Empire); uncertainty whether he was a Cuman or Kipchak, or mixed

- Elizabeth the Cuman

- Ladislaus IV of Hungary

- Mary of Hungary, Queen of Naples

- Anna of Hungary (1260–1281), daughter of Elizabeth the Cuman

- Elizabeth of Sicily, Queen of Hungary (Trouble with Cumans)

- Elizabeth of Hungary, Queen of Serbia was one of the older children of King Stephen V of Hungary and his wife Elizabeth the Cuman

- John Hunyadi had supposedly Tatar-Cuman origin, because his ancestors had Tartar-Cuman names

- Michael IX Palaiologos (17 April 1277 – 12 October 1320), son of Anna of Hungary

- Tsar Ivan Asen I of the Second Bulgarian Empire, established the Second Bulgarian Empire, with the help of his Cuman allies. First emperor of the new empire. The Asen dynasty is of Cuman origin,[citation needed] as well as the Terter dynasty/clan(which Kuthen was part of) and the Shishman dynasty

- Boril of Bulgaria (Boril Kaliman), 1207–1218, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Teodor I Peter IV, 1186–1197, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Ivan Asen II of the Second Bulgarian Empire, 1218–1241 [citation needed]

- Tsar Ivan Stephen Shishman, of the Second Bulgarian Empire, son of Michael III Shishman (confusion whether the name Shishman is Cuman or Bulgarian in origin) [citation needed]

- Tsar Kaloyan, Second Bulgarian Empire, defeated the crusaders with the help of his Cumans, captured Baldwin[citation needed]

- Tsar Kaliman I of Bulgaria (Kaliman Asen) of the Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Constantine Tikh of Bulgaria, 1257–1277 [citation needed]

- Tsar Michael Asen I of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Michael Asen II of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Michael Asen III of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Michael Asen IV оf Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Kaliman Asen II of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Mitso Asen of the Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar Ivan Asen III of the Second Bulgarian Empire [citation needed]

- Tsar George Terter I of the Second Bulgarian Empire, descended from the Cuman Terteroba clan

- Tsar George Terter II of the Second Bulgarian Empire, descended from the Cuman Terteroba clan

- TsarMichael III Shishman of the Second Bulgarian Empire (confusion whether the name Shishman is Cuman or Bulgarian in origin)

- Tsar Theodore Svetoslav of the Second Bulgarian Empire, son of George Terter I

- Tsar Ivan Alexander of the Second Bulgarian Empire, descended of the Asen, Terter and Shishman dynasties. Was Tsar during the second golden age of Bulgaria (naphew of Michael Shishman)

- Ivan Shishman of Bulgaria (b. 1350/1351, ruled 1371–1395 in Tarnovo)

- Tsar Ivan Shishman of the Second Bulgarian Empire. fourth son of Ivan Alexander

- Tsar Ivan Stratsimir of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire

- Tsar Boril of Bulgaria, Second Bulgarian Empire, descended from Cumans through the Asen dynasty of Bulgaria - of Cuman origin

- Constantine II, 1396–1422, spent most of his life in exile. Most historians do not include him in the list of the Bulgarian monarchs

- Ivan Sratsimir of Bulgaria (b. 1324/1325, ruled 1356–1397 in Vidin)

- Belaur of Vidin, 1336 (Shishman dynasty)

- Constantine II of Bulgaria (b. early 1370s, ruled 1397–1422 in Vidin and in exile)

- Darman and Kudelin - Bulgarians of Cuman origin

- Queen Dorothea of Bosnia

- Shishman of Vidin

- Lady Calinica

- Nicholas Alexander of Wallachia

- Thocomerius/Tihomir of Wallachia, father of Basarab. The Hungarian László Rásonyi derives the name from a well-known Cuman and Tatar name, Toq-tämir (‘hardened steel’)

- Every ruler from the Wallachian House of Dănești, which was one of the two main lineages of the Wallachian noble family House of Basarab. They were descended from Dan I of Wallachia. The other lineage of the Basarabs is the House of Drăculești

- The House of Drăculeşti were one of two major rival lines of Wallachian voivodes of the House of Basarab, the other being the Dăneşti. The following rulers of the House of Drăculeşti are of Cuman descent:

- Vlad II Dracul 1436–1442, 1443–1447; son of Mircea cel Bătrân

- Mircea II 1442; son of Vlad II

- Vlad III Drăculea, "Vlad the Impaler", "Dracula" 1448, 1456–1462, 1476; son of Vlad II

- Radu cel Frumos 1462–1473, 1474; son of Vlad II

- Vlad Călugărul 1481, 1482–1495; son of Vlad II

- Radu cel Mare 1495–1508; son of Vlad Călugărul

- Mihnea cel Rău 1508–1509; son of Vlad III

- Mircea III Dracul 1510; son of Mihnea cel Rău

- Vlad cel Tânăr 1510–1512; son of Vlad Călugărul

- Radu de la Afumaţi 1522–1523, 1524, 1524–1525, 1525–1529; son of Radu cel Mare

- Radu Bădica 1523–1524; son of Radu cel Mare

- Vlad Înecatul 1530–1532; son of Vlad cel Tânăr

- Vlad Vintilă de la Slatina 1532–1534, 1534–1535; son of Radu cel Mare

- Radu Paisie 1534, 1535–1545; son of Radu cel Mare

- Mircea the Shepherd 1545–1552, 1553–1554, 1558–1559; son of Radu cel Mare

- Pătraşcu cel Bun 1554–1558; son of Radu Paisie

- Petru cel Tânăr 1559–1568; son of Mircea the Shepherd

- Alexandru II Mircea 1568–1574, 1574–1577; son of Mircea III Dracul

- Vintilă 1574; son of Pătraşcu cel Bun

- Mihnea Turcitul 1577–1583, 1585–1591; son of Alexandru II Mircea

- Petru Cercel 1583–1585; son of Pătraşcu cel Bun

- Mihai Viteazul 1593–1600; possibly a son of Pătraşcu cel Bun

See also

- Cumania

- The Cuman Tsaritsa of Bulgaria

- Kumandins - a branch of the Cumans that still exists up to this day, in Siberia

- Delhi Sultanate - Qutb ad-Din Aibeg, founder of the Delhi sultanate, was a Cuman; redeemed from slavery by Afghan shakh Mahmud Ghuri, he became his governor in Delhi and proclaimed independence after the death of his patron.

- Igor Svyatoslavich

- Kipchak

- Nomad

- Kumyks

- Crimean Tatars

- Pechenegs

- Komnenos dynasty

- Komnina (Kozani), Greece

- Turkic peoples

- Turkic languages

- Battle of the Kalka River

- Mongol invasion of Rus

- Tatar invasions

- Crimean Karaites, an ethnic group possibly with Cuman origins

- Battle of the Stugna River

- Battle of Levounion

- Köten

- List of Tatar and Mongol raids against Rus'

- Mongol invasion of Europe

- History of Romania

- Crimean Karaites, an ethnic group with possible Cuman origins

- Kunság

- Bács-Kiskun County

- Kaloyan

- Cuman language

- Crimean Tatar language - possibly similar to the Cuman language

- Baibars

- Béla IV of Hungary

- Romania in the Early Middle Ages

- Stephen V of Hungary

- Foundation of Wallachia

- Battle of Adrianople (1205)

- Kunság

- Constantine Euphorbenos Katakalon

- Terter dynasty

- Basarab I of Wallachia

- Origin of the Romanians

- Anna of Hungary (1260–1281)

- Yaropolk II of Kiev

- Darman and Kudelin - Bulgarians of Cuman origin

- Elizabeth of Sicily, Queen of Hungary (Trouble with Cumans)

- Elizabeth of Hungary, Queen of Serbia -one of the older children of King Stephen V of Hungary and his wife Elizabeth the Cuman

- John Hunyadi - He had supposedly Tatar-Cuman origin, because his ancestors had Tartar-Cuman names

- Kumani Supporters Ultras group from Macedonia

- Shishman of Vidin (Shishman dynasty of the Second Bulgarian Empire is most probably of Cuman origin)

- Roman the Great - he waged two successful campaigns against the Cumans

- Ladislaus IV of Hungary - he was also known as King Ladislas the Cuman, son of Elizabeth the Cuman

- History of Transylvania

- Asen dynasty - dynasty of the Second Bulgarian Empire of Cuman origin

Notes

- ^ Loewenthal, Rudolf (1957). The Turkic Languages and Literatures of Central Asia: A Bibliography. Mouton. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Cuman

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, p. 563

- ^ Robert Lee Wolff: "The 'Second Bulgarian Empire.' Its Origin and History to 1204" Speculum, Volume 24, Issue 2 (April 1949), 179; "Thereafter, the influx of Pechenegs and Cumans turned Bulgaria into a battleground between Byzantium and these Turkish tribes..."

- ^ Bartusis, Mark C., The Late Byzantine Army: Arms and Society, 1204-1453, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 26; "Around 1239 a large group of Cumans--a Turkic people of the steppes...."

- ^ Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic nomads north of the Danube Delta from the tenth to the mid-thirteenth century. Leiden: Brill. p. 116.

- ^ "Cuman (people)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ a b c d http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-5359391/Mitochondrial-DNA-of-ancient-Cumanians.html

- ^ "Cumans". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ Cumans and Tatars, pg 7

- ^ a b c d e István Vásáry (2005) Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press. Cite error: The named reference "István Vásáry 2005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads, p. 186.

- ^ a b Laurențiu Rădvan, At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities, BRILL, 2010, p. 129

- ^ For example: "Bazarab infidelis Olahus noster", "Basarab Olacus et filii eiusdem", "Bazarab filium Thocomerius scismaticum olachis nostris". http://www.arcanum.hu/mol/lpext.dll/fejer/152e/153a/1654?fn=document-frame.htm&f=templates&2.0

- ^ István Vásáry (2005) Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press, p. 40: "No serious argument can be put forward in support of the Assenids' Bulgarian or Russian origin. Moreover, a Cuman name by itself cannot prove that its bearer was undoubtedly Cuman. Asen's Turkic name must be reconciled with the fact that the sources unanimously testify to his being Vlach."

- ^ Stephenson, Paul. Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ^ David Nicolle, Angus McBride, Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568, Osprey Publishing, 1988, p. 43

- ^ Ignjatić, Zdravko (2005). ESSE English-Serbian Serbian-English Dictionary and Grammar. Belgrade, Serbia: Institute for Foreign Languages. p. 1033. ISBN 867147122-5.

- ^ István Vásáry (2005) Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press, p. 6

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c d e http://encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkPath=pages\C\U\Cumans.htm

- ^ Matila Costiescu Ghyka, A documented chronology of Roumanian history from pre-historic times to the present day, B. H. Blackwell, ltd., 1941, p. 57

- ^ The meaning of "Vlach" in this case was the subject of fierce dispute in the late 19th and 20th centuries (see also Kaloyan of Bulgaria).

- ^ As mention in the Robert de Clari Chronicle

- ^ In his History of the Byzantine Empire (ISBN 978-0-299-80925-6, 1935), Russian historian A. A. Vasiliev concluded in this matter "The liberating movement of the second half of the 12th century in the Balkans was originated and vigorously prosecuted by the Wallachians, ancestors of the Romanians of today; it was joined by the Bulgarians, and to some extent by the Cumans from beyond the Danube "

- ^ a b Horvath 2001

- ^ Szakaly 2000.

- ^ Meszaros 2000.

- ^ Lango 2000a.

- ^ Nóra Berend, At the gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims, and "pagans" in medieval Hungary, c. 1000 - c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 72

- ^ a b c Linehan, Peter; Nelson, Janet Laughland, eds. (2003). The medieval world. Routledge Worlds Series. Vol. 10. Routledge. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-415-30234-0.

- ^ István Vásáry, Cumans and Tatars Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans 1185-1365, Cambridge University Press, 2005, pg 81.

- ^ Byzantine Armies AD 1118-1461, p.23, Ian Heath, 1995, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85532-347-6

- ^ a b Martyn C. Rady, Nobility, Land and Service in Medieval Hungary, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 90

- ^ Yule and Cordier 1916

- ^ http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-5359391/Mitochondrial-DNA-of-ancient-Cumanians.html.

- ^ Paloczi Horvath 1998, 2001.

- ^ http://doktori.bibl.u-szeged.hu/430/2/tz_en3387.pdf

- ^ As mentioned in Robert de Clari's chronicle.

- ^ Ovidiu Pecican Troia Venetia Roma

- ^ István Vásáry, Cumans and Tatars Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans 1185-1365, Cambridge University Press, 2005, 55-56.

- ^ Horváth (1989), p. 48.

- ^ Bonyak at the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ^ Spinei, Victor. The Cuman Bishopric - Genesis and Evolution. in The Other Europe: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars and Cumans. Edited by Florin Curta and Roman Kovalev. Brill Publishing. 2008. p. 64

- ^ Horvath 1978; Kovacs 1971; Sandor 1959.

- ^ "Mitochondrial DNA of ancient Cumanians: culturally Asian steppe nomadic immigrants with substantially more western Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages". Hum. Biol. 77 (5): 639–62. 2005. PMID 16596944.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Mitochondrial DNA of Ancient Cumanians: Culturally Asian Steppe Nomadic Immigrants with Substantially More Western Eurasian Mitochondrial DNA Lineages". Human Biology: pp. 639–662. 2005. http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/human_biology/v077/77.5szabo.html.

- ^ [doktori.bibl.u-szeged.hu/430/2/tz_en3387.pdf

Further reading

- Template:Ru icon Golubovsky Peter V. (1884) Pechenegs, Torks and Cumans before the invasion of the Tatars. History of the South Russian steppes in the 9th-13th Centuries (Печенеги, Торки и Половцы до нашествия татар. История южно-русских степей IX—XIII вв.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format.

- Template:Ru icon Golubovsky Peter V. (1889) Cumans in Hungary. Historical essay (Половцы в Венгрии. Исторический очерк) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format.

- István Vásáry (2005) "Cumans and Tatars", Cambridge University Press.

- Gyárfás István: A Jászkunok Története

- Györffy György: A Codex Cumanicus mai kérdései

- Györffy György: A magyarság keleti elemei

- Hunfalvy: Etnographia

- Perfecky (translator): Galician-Volhynian Chronicle