Georgian scripts

| Georgian alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 430 to present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Georgian and other Kartvelian languages |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Geor (240), Georgian (Mkhedruli and Mtavruli) Geok (241, Georgian scripts#Nuskhuri) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Georgian |

| U+10A0–U+10FF, U+2D00–U+2D2F | |

Template:Contains Georgian text

The Georgian alphabet is a graphically independent and unique alphabet used to write the Georgian language. It is a phonemic orthography and the modern alphabet has 33 letters.

The Georgian script can also be used to write other Kartvelian languages (Mingrelian, Svan, sometimes Laz), and occasionally other languages of the Caucasus such as Ossetian and Abkhaz during the 1940s.[1] Historically Ingush,[2] Chechen[3] and Avar languages[4][5] were written in the Georgian script, later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.

The Georgian word ანბანი (anbani) meaning "alphabet" is derived from the names of the first two letters of the three Georgian alphabets, which, although they look very different from one another, share the same alphabetic order and letter names. The alphabets can be seen mixed in some context, although Georgian is formally unicameral meaning there is normally no distinction between upper and lower case in any of the alphabets.

Origins

The origins of the Georgian alphabet are poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script, and the main influences on that process. The oldest uncontested example of Georgian writing is an inscription in the Asomtavruli script dated 430 AD, in a church in Bethlehem, Palestine. The oldest example of the script being used in Georgia is found in the church of Bolnisi Sioni, dated 494 AD.[6][7]

The scholarly consensus points to the Georgian alphabet being created in the early 5th century.[6] The first version of the alphabet attested is the Asomtavruli script; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian alphabet to the process of christianisation of the Georgian-speaking lands, that is Lazica (or Colchis) in the west, Kartli (or Iberia) in the east.[7] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bethlehem inscription of 430. It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[8]

A point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. Armenian tradition holds Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, to have also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[9] and has been widely quoted in Western academic sources,[10][11] but has been criticized by scholars, both Georgian[12] and Western,[8] who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation. Other scholars quote Koryun's claims without taking a stance on its validity.[13][14] Many agree, however, that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[15][16]

A competing Georgian tradition, first attested in medieval chronicles such as the Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[8] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaelogical confirmation has been found.[10][15][8] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternate interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglotography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[17]

Another scientific controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic writing systems such as Aramaic.[17] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[8][18] Some scholars have also suggested as a possible inspiration for particular letters certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers.[6]

Asomtavruli

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული), also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) is a historical, monumental and oldest form of the Georgian alphabet. Asomtavruli (ასომთავრული, "capital letters") derives from aso (ასო, "letter, type") and mtavari (მთავარი, "main, chief, principal, head"). Mrgvlovani (მრგვლოვანი, "rounded") is related to the word mrgvali (მრგვალი, "round"). Despite its common Georgian name, this rounded alphabet was originally purely unicameral, just like the modern Georgian alphabet. Examples of the earliest Asomtavruli scripts found in Nekresi are still preserved in the Georgian National Museum.

| Asomtavruli letters | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⴀ | Ⴁ | Ⴂ | Ⴃ | Ⴄ | Ⴅ | Ⴆ | Ⴡ | Ⴇ | Ⴈ | Ⴉ | Ⴊ | Ⴋ | Ⴌ |

| Ⴢ | Ⴍ | Ⴎ | Ⴏ | Ⴐ | Ⴑ | Ⴒ | Ⴣ | ႭჃ, Ⴓ | Ⴔ | Ⴕ | Ⴖ | Ⴗ | Ⴘ |

| Ⴙ | Ⴚ | Ⴛ | Ⴜ | Ⴝ | Ⴞ | Ⴤ | Ⴟ | Ⴠ | Ⴥ | ||||

| Some fonts for modern Georgian do not show the actual Asomtavruli forms for these letters, but instead show taller ("capitalized") variants of the modern Mkhedruli alphabet (see below). | |||||||||||||

This unicameral alphabet is still used today in some section headings and book titles, and sometimes used in a pseudo-bicameral way by varying the glyph sizes for creating capitals. Since it is no longer used for writing Georgian, it has also been reused in a creative way for writing capital letters, along with letters of one of the two other Georgian alphabets.

Incidentally, a unique local form of Aramaic writing known as Armazuli (არმაზული დამწერლობა, armazuli damts'erloba, i.e. the "Armazian script", derived from the name of the god Armazi) existed before that, as demonstrated by the 1940s discovery of a bilingual Greco-Aramaic inscription at Mtskheta, Georgia. It is conceivable that local pre-Christian records did exist, but were subsequently destroyed by zealous Christians. Therefore, many found more palatable the idea that the medieval Georgian chronicles crediting Parnavaz with the creation of Georgian writing actually refer to the introduction of a local form of written Aramaic during his reign.[19]

Asomtavruli is used by Georgian Orthodox Church.

-

Asomtavruli of Ishkhani.

-

Asomtavruli of Doliskana.

-

Asomtavruli of Barakoni.

-

Asomtavruli of Gudarekhi.

-

Asomtavruli of Kobayr monastery.

Nuskhuri

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური) ("minuscule, lowercase") is the ecclesiastical alphabet which first appeared in the 9th century. It was mostly used in hagiography. Nuskhuri is related to the word nuskha (ნუსხა "inventory, schedule").

| Nuskhuri letters | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⴀ | ⴁ | ⴂ | ⴃ | ⴄ | ⴅ | ⴆ | ⴡ | ⴇ | ⴈ | ⴉ | ⴊ | ⴋ | ⴌ |

| ⴢ | ⴍ | ⴎ | ⴏ | ⴐ | ⴑ | ⴒ | ⴣ | ⴍⴣ, ⴓ | ⴔ | ⴕ | ⴖ | ⴗ | ⴘ |

| ⴙ | ⴚ | ⴛ | ⴜ | ⴝ | ⴞ | ⴤ | ⴟ | ⴠ | ⴥ | ||||

The forms of the Khutsuri letters may have been derived from the northern Arsacid variant of the Pahlavi (or Middle Iranian) script, which itself was derived from the older Aramaic, although the direction of writing (from left to right), the use of separate symbols for the vowel sounds, the numerical values assigned to the letters in earlier times, and the order of the letters all point to significant Greek influence on the script.[20] However, the Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze argues that the forms of the letters are freely invented in imitation of the Greek model rather than directly based upon earlier forms of the Aramaic alphabet, even though the Georgian phonological inventory is very different from Greek. Like the monumental Asomtavruli alphabet, this squared alphabet was initially purely unicameral. However, it has also been used along with the Asomtavruli alphabet (serving as capital letters in religious manuscripts) to form the Khutsuri (ხუცური "ecclesiastical") bicameral style that is still used sometimes today. Nuskhuri is used by Georgian Orthodox Church.

-

Nuskhuri of Ioane-Zosime.

-

Nuskhuri of Tbeti.

-

Nuskhuri of the 11th century.

-

Nuskhuri of Mokvi.

Mkhedruli

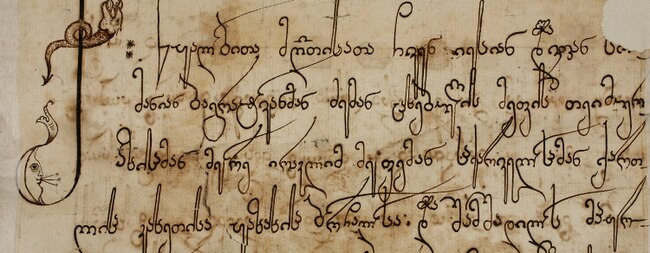

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული) ("cavalry" or "military") is the modern Georgian alphabet which first appeared in the 10th century. It was used for non-religious purposes up until the 19th century, when it completely replaced the Khutsuri style (that used the two previous alphabets). Mkhedruli is related to the word mkhedari (მხედარი, "horseman", "knight", or "warrior"); Khutsuri is related to the term khutsesi (ხუცესი, "elder" or "priest").

| Mkhedruli letters | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ა | ბ | გ | დ | ე | ვ | ზ | ჱ | თ | ი | კ | ლ | მ | ნ | |

| ჲ | ო | პ | ჟ | რ | ს | ტ | ჳ | უ | ფ | ქ | ღ | ყ | შ | |

| ჩ | ც | ძ | წ | ჭ | ხ | ჴ | ჯ | ჰ | ჵ | ჶ | ჷ | ჺ | ჸ | ჹ |

Like the two other alphabets, the Mkhedruli alphabet is purely unicameral. However, certain modern writers have experimented with using Asomtavruli letters as capitals, similarly to Khutsuri script style. In some cases, this may be a conflation with the religious Khutsuri style rather than the result of a creative design choice. Georgians often consider this bicameral use of Mkhedruli an error because some Mkhedruli letters lack equivalents in the other alphabets. Others use the Mkhedruli alphabet alone in a pseudo-bicameral way, adapting letter sizes to create capital letters, known as Mtavruli for titles and headings. Mtavruli (მთავრული) means "titlecase" and is an appropriate tribute to the older Asomtavruli.

-

Mkhedruli of King Bagrat IV of Georgia.

-

Mkhedruli of King George II of Georgia.

-

Mkhedruli of King David IV of Georgia.

-

Mkhedruli of Queen Tamar of Georgia.

-

Mkhedruli of King George IV of Georgia.

-

Mkhedruli of King George V of Georgia.

Other forms of some Mkhedruli letters

Some mkhedruli letters have alternative written forms.

- Different form of letter დ

- Different form of letter ლ

- Different form of letter ჯ

- Different form of letter რ

- Different form of letter ო

- Different form of letter წ

Obsolete letters

8 of the 41 Mkhedruli letters (shaded above) are now obsolete. Five of these, ⟨ჱ⟩ (he), ⟨ჲ⟩ (hie), ⟨ჳ⟩ (vie), ⟨ჴ⟩ (qar), and ⟨ჵ⟩ (hoe) were used in Old Georgian. These letters were discarded by the Society for the Spreading of Literacy Among Georgians, founded by Ilia Chavchavadze in 1879, and were either dropped entirely or replaced by the sounds they had become. The last three, ⟨ჶ⟩ (fi), ⟨ჷ⟩ (shva), and ⟨ჸ⟩ (elifi), were later additions to the Georgian alphabet used to represent sounds not present in Georgian proper, and are used to write other languages in the region. Also obsolete in modern Georgian is a variant of the letter ⟨უ⟩ (un), differentiated using a diacritic: ⟨უ̌⟩ or ⟨უ̂⟩.

- ⟨ჱ⟩ (he), sometimes called "ei" or "e-merve" ("eighth e"). As in Ancient Greek (Ηη, Ͱͱ, ēta), it holds the eighth place in the Georgian alphabet. The name and shapes of the letter in Asomtavruli ⟨Ⴡ⟩ and Nuskhuri ⟨ⴡ⟩ also resemble Greek's tack-shaped archaic consonantal heta. In old Georgian, he was interchangeable with the digraph ⟨ეჲ⟩. It represented [ei] or [ej].

- ⟨ჲ⟩ (hie), also called iot'a, often marked Georgian nouns in the nominative case. In Old Georgian, it represented [i] or [j].

- ⟨ჳ⟩ (vie) represented the diphthong [ui] or [uj]. It holds the same position and numerical value as Ancient Greek's Υυ upsilon, which its Asomtavruli ⟨Ⴣ⟩ and Nuskhuri ⟨ⴣ⟩ versions resemble. Its modern pronunciation is usually like ⟨უ⟩ [u] or ⟨ი⟩ [i].

- ⟨ჴ⟩ (qar, har) represented [q] or [qʰ], the non-ejective counterpart to ⟨ყ⟩ (q'ar) above. Although this consonant is still distinguished in Svan, its modern pronunciation in Georgian is identical to ⟨ხ⟩ [χ].

- ⟨ჵ⟩ (hoe), also called oh, represented a long ⟨ო⟩, [oː].

- ⟨ჶ⟩ (fi) was borrowed to represent the phoneme /f/ in loanwords from Latin and Greek such as ჶილოსოჶია (filosofia, 'philosophy'). Its name and shape derive from Greek. Its modern usage is a feature of Ossetic and Laz when written in the Georgian alphabet. In modern Georgian, ⟨ფ⟩ par replaces fi.

- ⟨ჷ⟩ (shva), also called yn, represents the mid central vowel [ə]. It appears in written Mingrelian, Laz, and Svan.

- ⟨ჸ⟩ (elifi) represents the glottal stop [ʔ]. Its name and pronunciation derive from Aramaic. It is used in written Mingrelian and rarely in Laz.

- ⟨უ̌⟩ or ⟨უ̂⟩ (un-brjgu) represented a short [u] in Old Georgian. It is still differentiated in Svan, Mingrelian, and Laz. In modern Georgian, it becomes ⟨ვ⟩ vin.

Ligatures and abbreviations

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Writing in Asomtavruli is often highly stylized. Since the time of Vakhtang I of Iberia in the 5th century, writers readily formed ligatures, intertwined letters, and placed letters within letters. The first ligature below was a feature of 6th-century Sassanid period currency. The second and third examples come from the arch of the David Gareja Monastery, pictured above. Ligatures flourished during the Middle Ages and could represent up to three letters.

Nuskhuri, like Asomtavruli is also often highly stylized. Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla. Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.[21] Some common examples include romeli, "which" (![]() , r~i) and Ieso Krist'e, "Jesus Christ" (

, r~i) and Ieso Krist'e, "Jesus Christ" (![]() , I~ui K~e).

, I~ui K~e).

In the 11th to 17th centuries, Mkhedruli also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adhesion to a complex system. For example, ⟨დ⟩ don and ⟨ა⟩ an make "da": ![]() .

.

In the older Asomtavruli, the sound /u/ was represented by the digraph ⟨ႭჃ⟩ or as ⟨Ⴓ⟩, a modified ⟨Ⴍ⟩. Nuskhuri saw the combination of the digraph ⟨ⴍⴣ⟩ into a ligature, ⟨ⴓ⟩ (cf. Greek ου, Cyrillic Ѹ/Ꙋ). However, Mkhedruli normally uses only ⟨უ⟩ as opposed to a digraph or ligature, and uses ⟨უ⟩ instead of obsolete ⟨ჳ⟩ (above) to represent the value 400.

| Asomtavruli ⟨Ⴂ⟩ gan and ⟨Ⴌ⟩ nar form a ligature.[8] | The word da (⟨ႣႠ⟩, "and") in Asomtavruli. | The word ars (⟨ႠႰႱ⟩, "be; is") in Asomtavruli. | Development of the letter un from a digraph through the three alphabets. |

Punctuation

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

Calligraphy

Georgian calligraphy is a centuries-old tradition of artistic writing of the Georgian language in its three Georgian alphabets.

Summary

This table lists the three alphabets in parallel columns, including the letters that are now obsolete (shown with a blue background). "National" is the transliteration system used by the Georgian government, while "Laz" is the system used in northeastern Turkey for the Laz language. The table also shows the traditional numeric values of the letters.[22]

| Letters | Unicode (mkhedruli) |

Name | IPA | Transcriptions | Numeric value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asomtavruli | nuskhuri | mkhedruli | National | ISO 9984 | BGN | Laz | ||||

| Ⴀ | ⴀ | ა | U+10D0 | an | /ɑ/ | A a | A a | A a | A a | 1 |

| Ⴁ | ⴁ | ბ | U+10D1 | ban | b | B b | B b | B b | B b | 2 |

| Ⴂ | ⴂ | გ | U+10D2 | gan | ɡ | G g | G g | G g | G g | 3 |

| Ⴃ | ⴃ | დ | U+10D3 | don | d | D d | D d | D d | D d | 4 |

| Ⴄ | ⴄ | ე | U+10D4 | en | ɛ | E e | E e | E e | E e | 5 |

| Ⴅ | ⴅ | ვ | U+10D5 | vin | v | V v | V v | V v | V v | 6 |

| Ⴆ | ⴆ | ზ | U+10D6 | zen | z | Z z | Z z | Z z | Z z | 7 |

| Ⴡ | ⴡ | ჱ | U+10F1 | he | Error using {{IPA symbol}}: "eɪ" not found in list | - | - | - | - | 8 |

| Ⴇ | ⴇ | თ | U+10D7 | tan | tʰ | T t | T' t' | T' t' | T t | 9 |

| Ⴈ | ⴈ | ი | U+10D8 | in | i | I i | I i | I i | I i | 10 |

| Ⴉ | ⴉ | კ | U+10D9 | k'an | kʼ | K' k' | K k | K k | K' k' | 20 |

| Ⴊ | ⴊ | ლ | U+10DA | las | l | L l | L l | L l | L l | 30 |

| Ⴋ | ⴋ | მ | U+10DB | man | m | M m | M m | M m | M m | 40 |

| Ⴌ | ⴌ | ნ | U+10DC | nar | n | N n | N n | N n | N n | 50 |

| Ⴢ | ⴢ | ჲ | U+10F2 | hie | i, j | - | - | - | - | 60 |

| Ⴍ | ⴍ | ო | U+10DD | on | ɔ | O o | O o | O o | O o | 70 |

| Ⴎ | ⴎ | პ | U+10DE | p'ar | pʼ | P' p' | P p | P p | P' p' | 80 |

| Ⴏ | ⴏ | ჟ | U+10DF | zhan | ʒ | Zh zh | Ž ž | Zh zh | J j | 90 |

| Ⴐ | ⴐ | რ | U+10E0 | rae | r | R r | R r | R r | R r | 100 |

| Ⴑ | ⴑ | ს | U+10E1 | san | s | S s | S s | S s | S s | 200 |

| Ⴒ | ⴒ | ტ | U+10E2 | t'ar | tʼ | T' t' | T t | T t | T' t' | 300 |

| Ⴣ | ⴣ | ჳ | U+10F3 | vie | /uɪ/ | - | - | - | - | 400* |

| Ⴓ | ⴓ | უ | U+10E3 | un | u | U u | U u | U u | U u | 400* |

| Ⴔ | ⴔ | ფ | U+10E4 | par | pʰ | P p | P' p' | P' p' | P p | 500 |

| Ⴕ | ⴕ | ქ | U+10E5 | kan | kʰ | K k | K' k' | K' k' | K k | 600 |

| Ⴖ | ⴖ | ღ | U+10E6 | ghan | ɣ | Gh gh | Ḡ ḡ | Gh gh | Ğ ğ | 700 |

| Ⴗ | ⴗ | ყ | U+10E7 | q'ar | qʼ | Q' q' | Q q | Q q | Q q | 800 |

| Ⴘ | ⴘ | შ | U+10E8 | shin | ʃ | Sh sh | Š š | Sh sh | Ş ş | 900 |

| Ⴙ | ⴙ | ჩ | U+10E9 | chin | tʃ[23] | Ch ch | Č' č' | Ch' ch' | Ç ç | 1000 |

| Ⴚ | ⴚ | ც | U+10EA | tsan | ts[23] | Ts ts | C' c' | Ts' ts' | Ts ts | 2000 |

| Ⴛ | ⴛ | ძ | U+10EB | dzil | dz | Dz dz | J j | Dz dz | Ž ž | 3000 |

| Ⴜ | ⴜ | წ | U+10EC | ts'il | tsʼ | Ts' ts' | C c | Ts ts | Ts' ts' | 4000 |

| Ⴝ | ⴝ | ჭ | U+10ED | ch'ar | tʃʼ | Ch' ch' | Č č | Ch ch | Ç' ç' | 5000 |

| Ⴞ | ⴞ | ხ | U+10EE | khan | x | Kh kh | X x | Kh kh | X x | 6000 |

| Ⴤ | ⴤ | ჴ | U+10F4 | qar, har | q, qʰ | - | - | - | - | 7000 |

| Ⴟ | ⴟ | ჯ | U+10EF | jan | dʒ | J j | J̌ ǰ | J j | C c | 8000 |

| Ⴠ | ⴠ | ჰ | U+10F0 | hae | h | H h | H h | H h | H h | 9000 |

| Ⴥ | ⴥ | ჵ | U+10F5 | hoe | oː | - | - | - | - | 10000 |

| (none) | (none) | ჶ | U+10F6 | fi | f | ? | ? | ? | ? | (none) |

* ჳ and უ have the same numeric value (400).

Unicode

The Georgian alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

History

In Unicode version 1.0 the U+10A0 ... U+10CF range of the Georgian block represented Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri). With the release of version 4.1 in March, 2005 Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri were "disunified". The U+10A0 ... U+10CF range of the Georgian block now represents Asomtavruli and the Georgian Supplement block represents Nuskhuri.

Blocks

The Unicode block for Georgian is U+10A0 ... U+10FF. Mkhedruli (modern Georgian) occupies the U+10D0 ... U+10FF range and Asomtavruli occupies the U+10A0 ... U+10CF range.

The Unicode block for Georgian Supplement is U+2D00 ... U+2D2F and it represents Nuskhuri.

| Georgian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10Ax | Ⴀ | Ⴁ | Ⴂ | Ⴃ | Ⴄ | Ⴅ | Ⴆ | Ⴇ | Ⴈ | Ⴉ | Ⴊ | Ⴋ | Ⴌ | Ⴍ | Ⴎ | Ⴏ |

| U+10Bx | Ⴐ | Ⴑ | Ⴒ | Ⴓ | Ⴔ | Ⴕ | Ⴖ | Ⴗ | Ⴘ | Ⴙ | Ⴚ | Ⴛ | Ⴜ | Ⴝ | Ⴞ | Ⴟ |

| U+10Cx | Ⴠ | Ⴡ | Ⴢ | Ⴣ | Ⴤ | Ⴥ | Ⴧ | Ⴭ | ||||||||

| U+10Dx | ა | ბ | გ | დ | ე | ვ | ზ | თ | ი | კ | ლ | მ | ნ | ო | პ | ჟ |

| U+10Ex | რ | ს | ტ | უ | ფ | ქ | ღ | ყ | შ | ჩ | ც | ძ | წ | ჭ | ხ | ჯ |

| U+10Fx | ჰ | ჱ | ჲ | ჳ | ჴ | ჵ | ჶ | ჷ | ჸ | ჹ | ჺ | ჻ | ჼ | ჽ | ჾ | ჿ |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Georgian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D0x | ⴀ | ⴁ | ⴂ | ⴃ | ⴄ | ⴅ | ⴆ | ⴇ | ⴈ | ⴉ | ⴊ | ⴋ | ⴌ | ⴍ | ⴎ | ⴏ |

| U+2D1x | ⴐ | ⴑ | ⴒ | ⴓ | ⴔ | ⴕ | ⴖ | ⴗ | ⴘ | ⴙ | ⴚ | ⴛ | ⴜ | ⴝ | ⴞ | ⴟ |

| U+2D2x | ⴠ | ⴡ | ⴢ | ⴣ | ⴤ | ⴥ | ⴧ | ⴭ | ||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

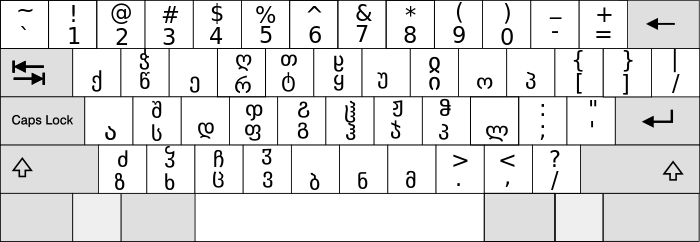

Keyboard layout

Most keyboards in Georgia are fitted with both Latin and Georgian letters.

Below is the Georgian QWERTY keyboard. While Georgian has no capital letters, because it has 33 letters and English has only 26, using the shift key is necessary to write Georgian.

Gallery

-

Georgian Asomtavruli and Mkhedruli inscriptions at Urbnisi.

-

Stylized Georgian letters of Asomtavruli script, 13th century

-

Georgian letter უ

-

Georgian letter ფ

-

Georgian Mkhedruli alphabet

-

Fragment from Zaza Panaskerteli's treatise on medicine

-

Sample of Georgian calligraphy

-

Georgian inscriptions from the Kobair Monastery

-

Inscrption from Mtskheta

-

Georgian Mkhedruli alphabet

-

An inscription in Mkhedruli at the Motsameta monastery, dating to ჩყმვ meaning 1846.

-

Georgian road signs in Georgian Mkhedruli and Latin alphabets.

-

Georgian inscriptions in Church of the Visitation of Israel.

-

Georgian Mkhedruli inscriptions.

-

Georgian Mkhedruli inscriptions at Tsalenjikha Cathedral.

-

Georgian Mkhedruli inscriptions

See also

- Georgian Braille

- Georgian calligraphy

- Old Georgian language

- Georgian calendar

- Georgian numerals

- Georgian national system of romanization

References

- ^ Georgian alphabet (Mkhedruli), Omniglot.com, retrieved 2009-04-22

- ^ Язык, история и культура вайнахов, И. Ю Алироев p85

- ^ Чеченский язык, И. Ю. Алироев, p24

- ^ Грузинско-дагестанские языковые контакты, Маджид Шарипович Халилов p29

- ^ История аварцев, М. Г Магомедов p150

- ^ a b c Harald Haarmann (2012). "Ethnic Conflict and standardisation in the Caucasus". In Matthias Hüning, Ulrike Vogl, Olivier Moliner (ed.). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b B. G. Hewitt (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Seibt, Werner. "The Creation of the Caucasian Alphabets as Phenomenon of Cultural History". Cite error: The named reference "Lig1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Koryun's Life of Mashtots

- ^ a b Donald Rayfield The Literature of Georgia: A History (Caucasus World). RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1163-5. P. 19. "The Georgian alphabet seems unlikely to have a pre-Christian origin, for the major archaeological monument of the 1st century 4IX the bilingual Armazi gravestone commemorating Serafua, daughter of the Georgian viceroy of Mtskheta, is inscribed in Greek and Aramaic only. It has been believed, and not only in Armenia, that all the Caucasian alphabets — Armenian, Georgian and Caucaso-Albanian — were invented in the 4th century by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots.<...> The Georgian chronicles The Life of Kartli - assert that a Georgian script was invented two centuries before Christ, an assertion unsupported by archaeology. There is a possibility that the Georgians, like many minor nations of the area, wrote in a foreign language — Persian, Aramaic, or Greek — and translated back as they read."

- ^ Glen Warren Bowersock, Peter Robert Lamont Brown, Oleg Grabar. Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-674-51173-5. P. 289. James R. Russell. Alphabets. "Mastoc' was a charismatic visionary who accomplished his task at a time when Armenia stood in danger of losing both its national identity, through partition, and its newly acquired Christian faith, through Sassanian pressure and reversion to paganism. By preaching in Armenian, he was able to undermine and co-opt the discourse founded in native tradition, and to create a counterweight against both Byzantine and Syriac cultural hegemony in the church. Mastoc' also created the Georgian and Caucasian-Albanian alphabets, based on the Armenian model."

- ^ Georgian: ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, გვ. 205-208, 240-245

- ^ Robert W. Thomson. Rewriting Caucasian history: the medieval Armenian adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles : the original Georgian texts and the Armenian adaptation. Clarendon Press, Oxford. p. xxii-xxiii. ISBN 0198263732.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Stephen H. Rapp. Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers, 2003. ISBN 90-429-1318-5. P. 450. "There is also the claim advanced by Koriwn in his saintly biography of Mashtoc' (Mesrop) that the Georgian script had been invented at the direction of Mashtoc'. Yet it is within the realm of possibility that this tradition, repeated by many later Armenian historians, may not have been part of the original fifth-century text at all but added after 607. Significantly, all of the extant MSS containing The Life of Mashtoc* were copied centuries after the split. Consequently, scribal manipulation reflecting post-schism (especially anti-Georgian) attitudes potentially contaminates all MSS copied after that time. It is therefore conceivable, though not yet proven, that valuable information about Georgia trans¬mitted by pre-schism Armenian texts was excised by later, post-schism individuals."

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Rapp2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Greppin, John A.C.: Some comments on the origin of the Georgian alphabet. — Bazmavep 139, 1981, 449-456

- ^ a b Nino Kemertelidze (1999). "The Origin of Kartuli (Georgian) Writing (Alphabet)". In David Cram, Andrew R. Linn, Elke Nowak (ed.). History of Linguistics 1996: Volume 1: Traditions in Linguistics Worldwide. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-90-272-8382-5. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Mzekala Shanidze (2000). "Greek influence in Georgian linguistics". In Sylvain Auroux; et al. (eds.). History of the Language Sciences / Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften / Histoire des sciences du langage. 1. Teilband. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 444–. ISBN 978-3-11-019400-5. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - ^ Stephen H. Rapp. Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers, 2003. ISBN 90-429-1318-5. P. 19. "Moreover, all surviving MSS written in Georgian postdate K'art'li's 4th-century conversion to Christianity. Not a shred of dated evidence has come to light confirming the invention of a Georgian alphabet by King P'arnavaz in the 3rd century ВС as is fabulously attested in the first text of K'C'<...> Cf. Chilashvili's "Nekresi" for the claim that a Geo. asomt'avruli burial inscription from Nekresi commemorates a Zoroastrian who died in the 1st/2nd century AD. Archaeological evidence confirms that a Zoroastrian temple once stood at Nekresi, but the date of the supposed grave marker is hopelessly circumstantial. Chilashvili reasons, on the basis of the 1st-/2nd-century date, that P'amavaz likely created the script in order to translate the Avesta (i.e.. sacred Zoroastrian writings) into Geo., thus turning on its head the argument that the Georgian script was deliberately fashioned by Christians in order to disseminate the New Testament. Though I accept eastern Georgia's intimate connection to Iran, I cannot support Chilashvili's dubious hypothesis. I find more palatable the idea that K'C actually refers to the introduction of a local form of written Aramaic during the reign of P'amavaz: Ceret'eli. "Aramaic," p. 243."

- ^ Armazi

- ^ Shanidze, Akaki (2003), ქართული ენა (in Georgian), Tbilisi, ISBN 1-4020-1440-6

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Aronson (1990), pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Aronson (1990) depicts the two affricates as aspirated, though other scholars, like Shosted & Chikovani (2006) describe them as voiceless.

Bibliography

- Aronson, Howard I. (1990), Georgian: a reading grammar (second ed.), Columbus, OH: Slavica

- Shosted, Ryan K.; Chikovani, Vakhtang (2006), "Standard Georgian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (2): 255–264, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002659