Space station

A space station, also known as an orbital station or an orbital space station, is a spacecraft capable of supporting a human crew in orbit for an extended period of time that lacks major propulsion or landing systems. Stations must have docking ports to allow other spacecraft to dock to transfer crew and supplies.

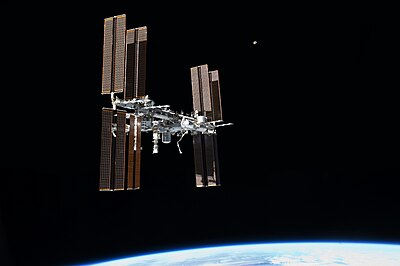

The purpose of maintaining an orbital outpost varies depending on the program. Space stations have most often been launched for scientific purposes, but military launches have also occurred. As of 2018[update], one fully operational and permanently inhabited space station is in low Earth orbit: the International Space Station (ISS), which is used to study the effects of long-term space flight on the human body as well as to provide a location to conduct a greater number and length of scientific studies than is possible on other space vehicles. China, India, Russia, and the U.S., as well as Bigelow Aerospace and Axiom Space, are all planning other stations for the coming decades.

History

The first mention of anything resembling a space station occurred in Edward Everett Hale's 1869 "The Brick Moon".[1] The first to give serious, scientifically grounded consideration to space stations were Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Hermann Oberth about two decades apart in the early 20th century.[2] In 1929 Herman Potočnik's The Problem of Space Travel was published, the first to envision a "rotating wheel" space station to create artificial gravity.[1] Conceptualized during the Second World War, the "sun gun" was a theoretical orbital weapon orbiting Earth at a height of 8,200 kilometres (5,100 mi). No further research was ever conducted.[3] In 1951, Wernher von Braun published a concept for a rotating wheel space station in Collier's Weekly, referencing Potočnik's idea. However, development of a rotating station was never begun in the 20th century.[2]

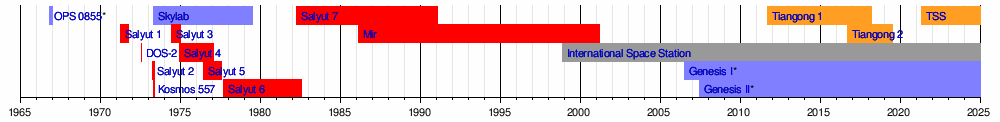

During the latter half of the 20th century, the Soviet Union developed and launched the world's first space station, Salyut 1.[4] The Almaz and Salyut series were eventually joined by Skylab, Mir, and Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2. The hardware developed during the initial Soviet efforts remains in use, with evolved variants a considerable part of the ISS space station orbiting today. Each crew member stays aboard the station for weeks or months, but rarely more than a year. Starting with the ill-fated flight of the Soyuz 11 crew to Salyut 1, all recent human spaceflight duration records have been set aboard space stations. The duration record for a single spaceflight is 437.75 days, set by Valeri Polyakov aboard Mir from 1994 to 1995. As of 2016[update], four cosmonauts have completed single missions of over a year, all aboard Mir. The last military-use space station was the Soviet Salyut 5, which was launched under the Almaz program and orbited between 1976 and 1977.[5]

Early monolithic stations (1971–1986)

Early stations were monolithic designs that were constructed and launched in one piece, generally containing all their supplies and experimental equipment. A crew would then be launched to join the station and perform research. After the supplies had been used up, the station was abandoned.[4]

The first space station was Salyut 1, which was launched by the Soviet Union on April 19, 1971. The earlier Soviet stations were all designated "Salyut", but among these there were two distinct types: civilian and military. The military stations, Salyut 2, Salyut 3, and Salyut 5, were also known as Almaz stations.[6]

The civilian stations Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 were built with two docking ports, which allowed a second crew to visit, bringing a new spacecraft with them; the Soyuz ferry could spend 90 days in space, at which point it needed to be replaced by a fresh Soyuz spacecraft.[7] This allowed for a crew to man the station continually. The American Skylab (1973-1979) was also equipped with two docking ports, like second-generation stations, but the extra port was never utilized. The presence of a second port on the new stations allowed Progress supply vehicles to be docked to the station, meaning that fresh supplies could be brought to aid long-duration missions. This concept was expanded on Salyut 7, which "hard docked" with a TKS tug shortly before it was abandoned; this served as a proof-of-concept for the use of modular space stations. The later Salyuts may reasonably be seen as a transition between the two groups.[6]

Mir (1986–2001)

Unlike previous stations, the Soviet space station Mir had a modular design; a core unit was launched, and additional modules, generally with a specific role, were later added to that. This method allows for greater flexibility in operation, as well as removing the need for a single immensely powerful launch vehicle. Modular stations are also designed from the outset to have their supplies provided by logistical support craft, which allows for a longer lifetime at the cost of requiring regular support launches.[8]

Modules are still being developed based on the design and capabilities of Mir.

Current

ISS (1998–present)

The ISS is divided into two main sections, the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the US Orbital Segment (USOS). The first module of the International Space Station, Zarya, was launched in 1998.[9]

The Russian Orbital Segment's "second-generation" modules were able to launch on Proton, fly to the correct orbit, and dock themselves without human intervention.[10] Connections are automatically made for power, data, gases, and propellants. The Russian autonomous approach allows the assembly of space stations prior to the launch of crew.

The Russian "second-generation" modules are able to be reconfigured to suit changing needs. As of 2009, RKK Energia was considering the removal and reuse of some modules of the ROS on the Orbital Piloted Assembly and Experiment Complex after the end of mission is reached for the ISS.[11] However, in September 2017 the head of Roscosmos said that the technical feasibility of separating the station to form OPSEK had been studied, and there were now no plans to separate the Russian segment from the ISS.[12]

In contract, the main USOS modules launched on the Space Shuttle and were attached to the ISS by crews during EVAs. Connections for electrical power, data, propulsion, and cooling fluids are also made at this time, resulting in a monolithic block of modules that is not designed for disassembly and must be deorbited as one mass.[13]

Tiangong program (2011–present)

China's first space laboratory, Tiangong-1 was launched in September 2011.[14] The uncrewed Shenzhou 8 then successfully performed an automatic rendezvous and docking in November 2011. The crewed Shenzhou 9 then docked with Tiangong-1 in June 2012, the crewed Shenzhou 10 in 2013. A second space laboratory Tiangong-2 was launched in September 2016, while a plan for Tiangong-3 was merged with Tiangong-2.[15]

In May 2017, China informed the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs that Tiangong-1's altitude was decaying and that it would soon reenter the atmosphere and break up.[15] The reentry was projected to occur in late March or early April 2018.[16] According to the China Manned Space Engineering Office, Tiangong-1 reentered over the South Pacific Ocean, northwest of Tahiti, on 2 April 2018 at 00:15 UTC.[17][18][19][20][21]

In July 2019 the China Manned Space Engineering Office announced that it was planning to deorbit Tiangong-2 in the near future, but no specific date was given.[22]

LOP-G (2019-current)

An international project intended to serve as a science platform and as a staging area for the lunar landings of NASA's Artemis program. The Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) started development during the now canceled Asteroid Redirect Mission. It was envisioned as a robotic, high performance solar electric spacecraft that would retrieve a multi-ton boulder from an asteroid and bring it to lunar orbit for study.[23] When ARM was cancelled, the concept was repurposed as the LOP-G propulsion system.[24][25] In May 2019, the PPE manufacturing contract was awarded.[26]

Planned projects

China: As of 2018, construction of the Chinese large modular space station was scheduled to begin in 2019 to receive crews by 2022.[27]

China: As of 2018, construction of the Chinese large modular space station was scheduled to begin in 2019 to receive crews by 2022.[27] U.S.: Bigelow Aerospace is developing the Bigelow Commercial Space Station using the B330 expandable spacecraft module and other modules. On 8 April 2016, a smaller scale Bigelow Expandable Activity Module was launched to the International Space Station to test expandable habitat technology in situ.[citation needed]

U.S.: Bigelow Aerospace is developing the Bigelow Commercial Space Station using the B330 expandable spacecraft module and other modules. On 8 April 2016, a smaller scale Bigelow Expandable Activity Module was launched to the International Space Station to test expandable habitat technology in situ.[citation needed] India: As of 2019, India is planning to begin flying the crewed Gaganyaan spacecraft by 2021.[28][29] The spacecraft is intended to be upgraded to perform rendezvous and docking after a first flight, with a 20 tonne space station intended to be built in the next 5–7 years.[30][31]

India: As of 2019, India is planning to begin flying the crewed Gaganyaan spacecraft by 2021.[28][29] The spacecraft is intended to be upgraded to perform rendezvous and docking after a first flight, with a 20 tonne space station intended to be built in the next 5–7 years.[30][31] U.S.: Starting in 2015, NASA was developing Deep Space Habitats (DSH) under the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) for Beyond Earth Orbit (BEO) spacestations and transfer vehicles.[32]

U.S.: Starting in 2015, NASA was developing Deep Space Habitats (DSH) under the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) for Beyond Earth Orbit (BEO) spacestations and transfer vehicles.[32] U.S.: NanoRacks, after finalizing its contract with NASA and winning NextSTEPs Phase II award, is now developing its concept Independence-1 (previously known as Ixion), which would be a wet workshop design to be tested in space.[citation needed]

U.S.: NanoRacks, after finalizing its contract with NASA and winning NextSTEPs Phase II award, is now developing its concept Independence-1 (previously known as Ixion), which would be a wet workshop design to be tested in space.[citation needed] Russia: Lunar Orbital Station

Russia: Lunar Orbital Station

Architecture

Two types of space stations have been flown: monolithic and modular. Monolithic stations consist of a single vehicle and are launched by one rocket. Modular stations consist of two or more separate vehicles that are launched independently and docked on orbit. Modular stations are currently preferred due to lower costs and greater flexibility. Both types can be refueled by cargo craft, such as Progress.[citation needed]

A space station is a complex vehicle that must incoporate many interrelated subsystems, including structure, electrical power, thermal control, attitude determination and control, orbital navigation and propulsion, automation and robotics, computing and communications, environmental and life support, crew facilities, and crew and cargo transportation. Stations must serve a useful role, which drives the capabilities required.[citation needed]

Habitability

The space station environment presents a variety of challenges to human habitability, including short-term problems such as the limited supplies of air, water and food and the need to manage waste heat, and long-term ones such as weightlessness and relatively high levels of ionizing radiation. These conditions can create long-term health problems for space-station inhabitants, including muscle atrophy, bone deterioration, balance disorders, eyesight disorders, and elevated risk of cancer.[33]

Future space habitats may attempt to address these issues, and could be designed for occupation beyond the weeks or months that current missions typically last. Possible solutions include the creation of artificial gravity by a rotating structure, the inclusion of radiation shielding, and the development of on-site agricultural ecosystems. Some designs might even accommodate large numbers of people, becoming essentially "cities in space" where people would reside semi-permanently. For now, no space station suitable for long-term human residence has ever been built, since the current launch costs for even a small station are not economically or politically viable.[34]

Environmental microbiology

Molds that develop aboard space stations can produce acids that degrade metal, glass and rubber. Despite an expanding array of molecular approaches for detecting microorganisms, rapid and robust means of assessing the differential viability of the microbial cells, as a function of phylogenetic lineage, remain elusive.[35]

List of space stations

The Soviet space stations came in two types, the civilian Durable Orbital Station (DOS), and the military Almaz stations.

Dates refer to periods when stations were inhabited by crews.

- Salyut space stations 1971–1986 (

Soviet Union) :

Soviet Union) :

- Salyut 1: 1971, 1 crew and 1 failed docking

- DOS-2: 1972, launch failure

- Salyut 2/Almaz: 1973, failed shortly after launch

- Kosmos 557: 1973, re-entered eleven days after launch

- Salyut 3/Almaz: 1974, 1 crew and 1 failed docking

- Salyut 4: 1975, 2 crews and 1 planned crew, failed to achieve orbit

- Salyut 5/Almaz: 1976–1977, 2 crews and 1 failed docking

- Salyut 6: 1977–1981, 16 crews (5 long duration, 11 short duration) and 1 failed docking

- Salyut 7: 1982–1986, 10 crews (6 long duration, 4 short duration) and 1 failed docking

- Skylab (

U.S.): 1973–1979, 3 crews

U.S.): 1973–1979, 3 crews - Mir (

Soviet Union/

Soviet Union/ Russia): 1986–2000, 28 long duration crews

Russia): 1986–2000, 28 long duration crews - International Space Station (ISS) (

Russia,

Russia,  United States,

United States,  EUR,

EUR,  Japan and

Japan and  Canada): 2000–ongoing, 60 Expedition crews (as of July 2019)

Canada): 2000–ongoing, 60 Expedition crews (as of July 2019) - Tiangong program (

China): 2011–ongoing

China): 2011–ongoing

- Tiangong-1: 2011–2018, 2 crews

- Tiangong-2: 2016–2019, 1 crew, 1 uncrewed resupply vessel

Canceled projects

U.S.: USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) project was an explicitly military project that was canceled in 1969, about a year before the first planned test flight.[citation needed]

U.S.: USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) project was an explicitly military project that was canceled in 1969, about a year before the first planned test flight.[citation needed] U.S.: Skylab B was manufactured as a backup article; due to the high costs of a Saturn launches and a desire by NASA to move entirely to STS operations it was never flown. The hull is on display at the National Air and Space Museum.

U.S.: Skylab B was manufactured as a backup article; due to the high costs of a Saturn launches and a desire by NASA to move entirely to STS operations it was never flown. The hull is on display at the National Air and Space Museum. Soviet Union: A number of additional Salyuts were produced, as backups or as flight articles for launches that were later canceled.[citation needed]

Soviet Union: A number of additional Salyuts were produced, as backups or as flight articles for launches that were later canceled.[citation needed] U.S.: Space Station Freedom program was under development for ten years, but was never launched, instead evolving into the International Space Station.[citation needed]

U.S.: Space Station Freedom program was under development for ten years, but was never launched, instead evolving into the International Space Station.[citation needed] Russia: The Soviet/Russian Mir-2 station was never fully constructed, but some modules, such as Zvezda, were used to build the International Space Station.

Russia: The Soviet/Russian Mir-2 station was never fully constructed, but some modules, such as Zvezda, were used to build the International Space Station.- The Industrial Space Facility was a station proposed in the 1980s. The project was canceled when Space Industries Incorporated was unable to secure funding from the United States government.[36]

European Union: The European Columbus project planned to launch a small space station serviced by the Hermes shuttle. It evolved into the ISS Columbus module.

European Union: The European Columbus project planned to launch a small space station serviced by the Hermes shuttle. It evolved into the ISS Columbus module. Isle of Man: Excalibur Almaz was developing a reusable space vehicle and a space station based on "Almaz" technology for flight in the early 2010s.[37] In March 2016, plans were announced to have the equipment converted into an educational exhibit, owing to lack of funds.[38]

Isle of Man: Excalibur Almaz was developing a reusable space vehicle and a space station based on "Almaz" technology for flight in the early 2010s.[37] In March 2016, plans were announced to have the equipment converted into an educational exhibit, owing to lack of funds.[38] U.S.: In December 2011 Boeing proposed an Exploration Gateway Platform to be constructed at the ISS and relocated via space tug to an Earth-Moon Lagrange point (EML-1 or 2). The purpose of the platform would be to serve as a propellant depot and to support lunar landing missions.[39]

U.S.: In December 2011 Boeing proposed an Exploration Gateway Platform to be constructed at the ISS and relocated via space tug to an Earth-Moon Lagrange point (EML-1 or 2). The purpose of the platform would be to serve as a propellant depot and to support lunar landing missions.[39]

See also

- List of space stations

- List of films featuring space stations

- Lunar outpost

- Martian outpost

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

References

- ^ a b Mann, Adam (January 25, 2012). "Strange Forgotten Space Station Concepts That Never Flew". Wired. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "The First Space Station". Boys' Life. September 1989. p. 20.

- ^ "Science: Sun Gun". Time. July 9, 1945.

- ^ a b Ivanovich, Grujica S. (2008). Salyut – The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73973-1. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Russian Space Stations (wikisource)

- ^ a b Chladek, Jay (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2292-2. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ D.S.F. Portree (1995). "Mir Hardware Heritage" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hall, R., ed. (2000). The History of Mir 1986–2000. British Interplanetary Society. ISBN 978-0-9506597-4-9.

- ^ "History and Timeline of the ISS". Center for the Advancement of Science in Space. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering" (PDF). Usu.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (22 May 2009). "Russia 'to save its ISS modules'". BBC News. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (25 September 2017). "International partners in no rush regarding future of ISS". SpaceNews. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Thomas Kelly; et al. (2000). Engineering Challenges to the Long-Term {{subst:lc:Operation}} of the International Space Station. National Academies Press. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-309-06938-0.

- ^ Barbosa, Rui. "China launches TianGong-1 to mark next human space flight milestone". NASASpaceflight.com.

- ^ a b Dickinson, David (10 November 2017). "China's Tiangong 1 Space Station to Burn Up". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Byrd, Deborah (March 7, 2018). "China's Tiangong-1 due for uncontrolled re-entry, soon". EarthSky. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "Tracking and Impact Prediction". Space-Track.Org. JFSCC/J3. 1 April 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ 18 Space Control Squadron. "18 SPCS on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

UPDATE: #JFSCC confirmed #Tiangong1 reentered the atmosphere over the southern Pacific Ocean at ~5:16 p.m. (PST) April 1. For details see http://www.space-track.org @US_Stratcom @usairforce @AFSpaceCC @30thSpaceWing @PeteAFB @SpaceTrackOrg

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ "Tiangong-1 reenters the atmosphere". cmse.gov.cn. China Manned Space. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Staff (1 April 2018). "Tiangong-1: Defunct China space lab comes down over South Pacific". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (1 April 2018). "China's Tiangong-1 Space Station Has Fallen Back to Earth Over the Pacific". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (12 July 2019). "China set to carry out controlled deorbiting of Tiangong-2 space lab". SpaceNews. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Greicius, Tony (2016-09-20). "JPL Seeks Robotic Spacecraft Development for Asteroid Redirect Mission". NASA. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ "NASA closing out Asteroid Redirect Mission". SpaceNews.com. 2017-06-14. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ "Asteroid Redirect Robotic Mission". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ Jeff Foust (May 23, 2019). "NASA selects Maxar to build first Gateway element". SpaceNews. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "China to begin construction of manned space station in 2019". Reuters. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "ISRO Looks Beyond Manned Mission; Gaganyaan Aims to Include Women".

- ^ "India eying an indigenous station in space". The Hindu Business Line. June 13, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- ^ "India's own space station to come up in 5–7 years: Isro chief – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- ^ "India Planning to Launch Its Own 'Small' Space Station Soon, Announces ISRO Chief K Sivan". www-news18-com.cdn.ampproject.org. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- ^ Doug Messier (August 11, 2016). "A Closer Look at NextSTEP-2 Deep Space Habitat Concepts". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (27 January 2014). "Beings Not Made for Space". New York Times. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Space Settlements: A Design Study". NASA. 1975. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Trudy E. Bell (2007). "Preventing "Sick" Spaceships".

- ^ Kaplan, David (August 25, 2007). "Space station idea was far-out at the time". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ "Excalibur-Almaz showcases space vehicles and space stations". SpaceRef. 6 June 2011.

- ^ Owen, Jonathan (11 March 2015). "Shooting for the Moon: time called on Isle of Man space race". The Independent. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Exploration Gateway Platform hosting Reusable Lunar Lander proposed". NASASpaceFlight.com. 2011-12-02. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

Bibliography

- Chladek, Jay (2017). Outposts on the Frontier: A Fifty-Year History of Space Stations. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2292-2.

- Haeuplik-Meusburger: Architecture for Astronauts – An Activity based Approach. Springer Praxis Books, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7091-0666-2.

- Grujica S. Ivanovich (July 7, 2008). Salyut: the first space station: triumph and tragedy. Praxis. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-387-73585-6.

- Neri Vela, Rodolfo (1990). Manned space stations" Their construction, operation and potential application. Paris: European Space Agency SP-1137. ISBN 978-92-9092-124-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)

External links

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Space Stations

- "Giant Doughnut Purposed as Space Station", Popular Science, October 1951, pp. 120–121; article on the subject of space exploration and a space station orbiting earth