Little Richard

Little Richard | |

|---|---|

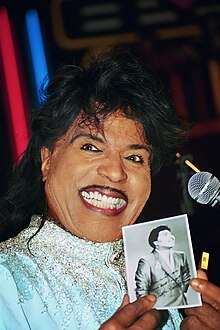

Little Richard in 2007 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Richard Wayne Penniman |

| Born | December 5, 1932 Macon, Georgia, US |

| Genres | Rock and roll, rhythm and blues, gospel, soul |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, pianist |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, piano |

| Years active | 1947–2013[1] |

| Labels | RCA Victor, Peacock, Specialty, End, Ronnex, London, Goldisc Records, Little Star Records, Mercury, Atlantic, Vee-Jay, Modern, Okeh, Brunswick, Reprise, K-Tel, Warner Bros., Disney |

Richard Wayne Penniman (born December 5, 1932),[2] known as Little Richard, is a retired American musician, singer and songwriter.

An influential figure in popular music and culture for seven decades, Penniman's most celebrated work dates from the mid-1950s, when his dynamic music and charismatic showmanship laid the foundation for rock and roll. His music also played a key role in the formation of other popular music genres, including soul and funk. Penniman influenced numerous singers and musicians across musical genres from rock to hip hop; his music helped shape rhythm and blues for generations to come, and his performances and headline-making thrust his career right into the mix of American popular music.

Penniman has been honored by many institutions. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as part of its first group of inductees in 1986. He was also inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. He is the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. Little Richard's "Tutti Frutti" (1955) was included in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2010, which stated that his "unique vocalizing over the irresistible beat announced a new era in music."

In 2015, the National Museum of African American Music[3] honored Little Richard with a Rhapsody & Rhythm Award for his pivotal role in the formation of popular music genres and in helping to shatter the color line[clarification needed] on the music charts, changing American culture significantly.

Early life

Little Richard was born Richard Wayne Penniman on December 5, 1932, in Macon, Georgia. He was the third of twelve children of Leva Mae (née Stewart) and Charles "Bud" Penniman. His father was a church deacon who sold bootlegged moonshine on the side and owned a nightclub, the Tip In Inn.[4][5] His mother was a member of Macon's New Hope Baptist Church.[6] Initially, Penniman's first name was supposed to have been "Ricardo" but an error resulted in "Richard" instead.[4][7] The Penniman children were raised in a neighborhood of Macon called Pleasant Hill.[6] In childhood, he was nicknamed "Lil' Richard" by his family, because of his small and skinny frame. A mischievous child who played pranks on neighbors, Penniman began singing in church at a young age.[8][9] Possibly as a result of complications at birth, Penniman had a slight deformity that left one of his legs shorter than the other. This produced an unusual gait; he was mocked for his allegedly effeminate appearance.[10]

Penniman's family was very religious, joining various A.M.E., Baptist and Pentecostal churches, with some family members becoming ministers. Penniman enjoyed the Pentecostal churches the most, because of their charismatic worship and live music.[11] He later recalled that people in his neighborhood during segregation sang gospel songs throughout the day to keep a positive outlook, because "there was so much poverty, so much prejudice in those days".[12] He had observed that people sang "to feel their connection with God" and to wash their trials and burdens away.[13] Gifted with a loud singing voice, Penniman recalled that he was "always changing the key upwards" and that they once stopped him from singing in church for "screaming and hollering" so loud, earning him the nickname "War Hawk".[14] As a child, Penniman would "beat on the steps of the house, and on tin cans and pots and pans, or whatever", while singing, annoying neighbors.[15]

Penniman's initial musical influences were gospel performers such as Brother Joe May, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Mahalia Jackson and Marion Williams. May, who as a singing evangelist was known as "the Thunderbolt of the Middle West" because of his phenomenal range and vocal power, inspired the boy to become a preacher.[16][17] Penniman attended Macon's Hudson High School,[18] where he was a below-average student. Penniman eventually learned to play alto saxophone joining his school's marching band while in fifth grade.[15] While in high school, Penniman obtained a part-time job at Macon City Auditorium for local secular and gospel concert promoter Clint Brantley. Penniman sold Coca-Cola to crowds during concerts of star performers of the day such as Cab Calloway, Lucky Millinder and his favorite singer, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.[19]

Music career

Beginnings (1947–1955)

In October 1947, 14-year-old Penniman performed with Tharpe at the Macon City Auditorium. After the show Tharpe paid him, inspiring him to become a professional performer.[19][20] However, Penniman said he was inspired to play the piano after he heard Ike Turner's piano intro on "Rocket 88."[21] In 1949, he began performing in Doctor Nubillo's traveling show. Penniman was inspired to wear turbans and capes in his career by Nubillo, who also "carried a black stick and exhibited something he called 'the devil's child' - the dried-up body of a baby with claw feet like a bird and horns on its head." Nubillo told Penniman he was "gonna be famous" but that he would have to "go where the grass is greener."[22]

Before entering the tenth grade, Penniman left his family home and joined Dr. Hudson's Medicine Show in 1949, performing Louis Jordan's "Caldonia".[22] Penniman recalled the song was the first secular R&B song he learned, since his family had strict rules against playing R&B music, which they considered "devil music."[23] Penniman also performed in drag during this time, performing under the name "Princess LaVonne".[24] In 1950, Penniman joined his first musical band, Buster Brown's Orchestra, where Brown gave him the name Little Richard.[25] Performing in the minstrel show circuit, Penniman, in and out of drag, performed for various vaudeville acts such as Sugarfoot Sam from Alabam, the Tidy Jolly Steppers, the King Brothers Circus and Broadway Follies.[26] Having settled in Atlanta, Georgia at this point, Penniman began listening to rhythm and blues and frequented Atlanta clubs, including the Harlem Theater and the Royal Peacock where he saw performers such as Roy Brown and Billy Wright onstage. Penniman was further influenced by Brown's and Wright's flashy style of showmanship and was even more influenced by Wright's flamboyant persona and showmanship. Inspired by Brown and Wright, Penniman decided to become a rhythm and blues singer and after befriending Wright, began to learn how to be an entertainer from him, and began adapting a pompadour hairdo similar to Wright's, as well as styling a pencil mustache, using Wright's brand of facial pancake makeup and wearing flashier clothes.[27]

Impressed by his singing voice, Wright put him in contact with Zenas Sears, a local deejay. Sears recorded Penniman at his station, backed by Wright's band. The recordings led to a contract that year with RCA Victor.[28] Penniman recorded a total of eight sides for RCA Victor, including the blues ballad, "Every Hour," which became his first single and a hit in Georgia.[28] The release of "Every Hour" improved his relationship with his father, who began regularly playing the song on his nightclub jukebox.[28] Shortly after the release of "Every Hour", Penniman was hired to front Perry Welch and His Orchestra and played at clubs and army bases for $100 a week.[29] After a year with RCA Victor, Penniman left the label in February 1952 after his records there failed to become national hits. That same month, Penniman's father Bud was killed after a confrontation outside his club. Penniman continued to perform during this time and Clint Brantley agreed to manage Penniman's career. Moving to Houston, he formed a band called the Tempo Toppers, performing as part of blues package tours in Southern clubs such as Club Tijuana in New Orleans and Club Matinee in Houston. Penniman signed with Don Robey's Peacock Records in February 1953, recording eight sides, including four with Johnny Otis and his band that were unreleased at the time.[30] Like his venture with RCA Victor, none of Penniman's Peacock singles charted despite Penniman's growing reputation for his high energy antics onstage.[31] Penniman began complaining of monetary issues with Robey, resulting in Penniman getting knocked out by Robey during a scuffle. Disillusioned by the record business, Penniman returned to Macon in 1954 and, struggling with poverty, settled for work as a dishwasher for Greyhound Lines. That year, he disbanded the Tempo Toppers and formed a harder-driving rhythm and blues band, the Upsetters, which included drummer Charles Connor and saxophonist Wilbert "Lee Diamond" Smith and toured under Brantley's management.[32][33][34] The band supported R&B singer Christine Kittrell on some recordings, then began to tour successfully, even without a bass guitarist, forcing drummer Connor to thump "real hard" on his bass drum in order to get a "bass fiddle effect."[32] Around this time, Penniman signed a contract to tour with fellow R&B singer Little Johnny Taylor.

At the suggestion of Lloyd Price, Penniman sent a demo to Price's label, Specialty Records, in February 1955. Months passed before Penniman got a call from the label.[35] Finally in September of that year, Specialty owner Art Rupe loaned Penniman money to buy out of his Peacock contract and set him to work with producer Robert "Bumps" Blackwell.[36] Upon hearing Penniman's demo, Blackwell felt Penniman was Specialty's answer to Ray Charles, however, Penniman told him he preferred the sound of Fats Domino. Blackwell sent him to New Orleans where he recorded at Cosimo Matassa's J&M Studios, recording there with several of Domino's session musicians, including drummer Earl Palmer and saxophonist Lee Allen.[37] Initially, Penniman's recordings that month failed to produce much inspiration or interest. Frustrated, Blackwell and Penniman went to relax at the Dew Drop Inn nightclub. According to Blackwell, Penniman then launched into a risqué dirty blues he titled "Tutti Frutti". Blackwell said he felt the song had hit potential and hired songwriter Dorothy LaBostrie to replace some of Little Richard's sexual lyrics with less controversial words.[38][39] Recorded in three takes in September 1955, "Tutti Frutti" was released as a single that November.[40]

Initial success and conversion (1955–1962)

A lot of songs I sang to crowds first to watch their reaction. That's how I knew they'd hit.

—Little Richard[41]

"Tutti Frutti" became an instant hit, reaching No. 2 on Billboard magazine's Rhythm and Blues Best-Sellers chart and crossing over to the pop charts in both the United States and overseas in the United Kingdom. It reached No. 21 on the Billboard Top 100 in America and No. 29 on the British singles chart, eventually selling a million copies.[31][42]

Penniman's next hit single, "Long Tall Sally" (1956), hit number one on the R&B chart and number 13 on the Top 100 while reaching the top ten in Britain. Like "Tutti Frutti", it sold over a million copies. Following his success, Little Richard built up his backup band, The Upsetters, with the addition of saxophonists Clifford "Gene" Burks and leader Grady Gaines, bassist Olsie "Baysee" Robinson and guitarist Nathaniel "Buster" Douglas.[43] Penniman began performing on package tours across the United States. Art Rupe described the differences between Penniman and a similar hitmaker of the early rock and roll period by stating that, while "the similarities between Little Richard and Fats Domino for recording purposes were close", Penniman would sometimes stand up at the piano while he was recording and that onstage, where Domino was "plodding, very slow", Penniman was "very dynamic, completely uninhibited, unpredictable, wild. So the band took on the ambience of the vocalist."[44]

Penniman's performances, like most early rock and roll shows, resulted in integrated audience reaction during an era where public places were divided into "white" and "colored" domains. In these package tours, Penniman and other artists such as Fats Domino and Chuck Berry would enable audiences of both races to enter the building, albeit still segregated (e.g. blacks on the balcony and whites on the main floor). As his bandleader at the time, H.B. Barnum, explained, Penniman's performances enabled audiences to come together to dance.[45] Despite broadcasts on TV from local supremacist groups such as the North Alabama White Citizens Council warning that rock and roll "brings the races together," Penniman's popularity was helping to shatter the myth that black performers could not successfully perform at "white-only venues," especially in the South where racism was most overt.[46] Penniman's high-energy antics included lifting his leg while playing the piano, climbing on top of his piano, running on and off the stage and throwing his souvenirs to the audience.[47] Penniman also began using capes and suits studded with multi-colored precious stones and sequins. Penniman said he began to be more flamboyant onstage so no one would think he was "after the white girls".[48]

Penniman claims that a show at Baltimore's Royal Theatre in June 1956 led to women throwing their undergarments onstage at him, resulting in other female fans repeating the action, saying it was "the first time" that had happened to any artist.[49] Penniman's show would stop several times that night due to fans being restrained from jumping off the balcony and then rushing to the stage to touch Penniman. Overall, Penniman would produce seven singles in the United States alone in 1956, with five of them also charting in the UK, including "Slippin' and Slidin'", "Rip It Up", "Ready Teddy", "The Girl Can't Help It" and "Lucille". Immediately after releasing "Tutti Frutti", which was then protocol for the industry, "safer" white recording artists such as Pat Boone re-recorded the song, sending the song to the top twenty of the charts, several positions higher than Penniman's. At the same time, fellow rock and roll peers such as Elvis Presley and Bill Haley also recorded Penniman's songs later in the year. Befriending Alan Freed, Freed eventually put him in his "rock and roll" movies such as Don't Knock the Rock and Mister Rock and Roll. In 1957, Penniman was giving a larger singing role in the film, The Girl Can't Help It.[50] That year, he scored more hit success with songs such as "Jenny, Jenny" and "Keep A-Knockin'" the latter becoming his first top ten single on the Billboard Top 100. By the time he left Specialty in 1959, Penniman had scored a total of nine top 40 pop singles and seventeen top 40 R&B singles.[51][52]

Penniman performed at the famed twelfth Cavalcade of Jazz held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on September 2, 1956. Also performing that day were Dinah Washington, The Mel Williams Dots, Julie Stevens, Chuck Higgin's Orchestra, Bo Rhambo, Willie Hayden & Five Black Birds, The Premiers, Gerald Wilson and His 20-Pc. Recording Orchestra and Jerry Gray and his Orchestra.[53][54]

Shortly after the release of "Tutti Frutti", Penniman relocated to Los Angeles. After achieving success as a recording artist and live performer, Penniman settled at a wealthy, formerly predominantly white neighborhood, living close to black celebrities such as boxer Joe Louis.[55] Penniman's first album, Here's Little Richard, was released by Specialty in May 1957 and peaked at number thirteen on the Billboard Top LPs chart. Similar to most albums released during that era, the album featured six released singles and "filler" tracks.[56] In early 1958, Specialty released his second album, Little Richard, which didn't chart. In October 1957, Penniman embarked on a package tour in Australia with Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran. During the middle of the tour, he shocked the public by announcing he was following a life in the ministry.[57] Penniman would claim in his autobiography that during a flight from Melbourne to Sydney that his plane was experiencing some difficulty and he claimed to have seen the plane's red hot engines and felt angels were "holding it up".[58] At the end of his Sydney performance, Penniman saw a bright red fireball flying across the sky above him and claimed he was "deeply shaken".[58] Though it was eventually told to him that it was the launching of the first artificial Earth satellite Sputnik 1, Penniman claimed he took it as a "sign from God" to repent from performing secular music and his wild lifestyle at the time.[57]

Returning to the States ten days earlier than expected, Penniman read news of his original flight having crashed into the Pacific Ocean as a further sign to "do as God wanted".[59] After a "farewell performance" at the Apollo Theater and a "final" recording session with Specialty later that month, Penniman enrolled at Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama, to study theology.[60][61] Despite his claims of spiritual rebirth, Penniman admitted his reasons for leaving were more monetary. During his tenure at Specialty, despite earning millions for the label, Penniman complained that he did not know the label had cut the percentage of royalties he was to earn for his recordings.[62] Specialty continued to release Penniman recordings, including "Good Golly, Miss Molly" and his version of “Kansas City”, until 1960. Finally ending his contract with the label, Penniman agreed to relinquish any royalties for his material.[63] In 1958, Penniman formed the Little Richard Evangelistic Team, traveling across the country to preach.[64] A month after his conversion, Penniman met Ernestine Harvin, a secretary from Washington, D.C., and the couple married on July 11, 1959.[65] Penniman ventured into gospel music, first recording for End Records, before signing with Mercury Records in 1961, where he eventually released King of the Gospel Singers, in 1962, produced by Quincy Jones, who later remarked that Penniman's vocals impressed him more than any other vocalist he had worked with.[66] His childhood heroine, Mahalia Jackson, wrote in the liner notes of the album that Penniman "sang gospel the way it should be sung".[67] While Penniman was no longer charting in the US, some of his gospel songs such as "He's Not Just a Soldier" and "He Got What He Wanted", reached the pop charts in the US and the UK. [68]

Return to secular music (1962–1979)

I heard so much about the audience reaction, I thought there must be some exaggeration. But it was all true. He drove the whole house into a complete frenzy ... I couldn't believe the power of Little Richard onstage. He was amazing.

—Mick Jagger[69]

In 1962, concert promoter Don Arden persuaded Little Richard to tour Europe after telling him his records were still selling well there. With fellow rock singer Sam Cooke as an opening act, Penniman, who featured a teenage Billy Preston in his gospel band, figured it was a gospel tour and, after Cooke's delayed arrival forced him to cancel his show on the opening date, performed only gospel material on the show, leading to boos from the audience expecting Penniman to sing his rock and roll hits. The following night, Penniman viewed Cooke's well received performance. Bringing back his competitive drive, Penniman and Preston warmed up in darkness before launching into "Long Tall Sally", resulting in frenetic, hysterical responses from the audience. A show at Mansfield's Granada Theatre ended early after fans rushed the stage.[70] Hearing of Penniman's shows, Brian Epstein, manager of The Beatles, asked Don Arden to allow his band to open for Penniman on some tour dates, to which he agreed. The first show for which the Beatles opened was at New Brighton's Tower Ballroom that October.[71] The following month they, along with Swedish singer Jerry Williams and his band The Violents,[72] opened for Little Richard at the Star-Club in Hamburg.[73] During this time, Little Richard advised the group on how to perform his songs and taught Paul McCartney his distinctive vocalizations.[73] Back in the US, Little Richard recorded six rock and roll songs with the Upsetters for Little Star Records, under the name "World Famous Upsetters", hoping this would keep his options open in maintaining his position as a minister.

In the fall of 1963, Penniman was called by a concert promoter to rescue a sagging tour featuring The Everly Brothers, Bo Diddley and The Rolling Stones. Penniman agreed and helped to save the tour from flopping. At the end of that tour, Penniman was given his own TV special for Granada Television titled The Little Richard Spectacular. The special became a ratings hit and after 60,000 fan letters, was rebroadcast twice.[74] In 1964, now openly re-embracing rock and roll again, Penniman released "Bama Lama Bama Loo" on Specialty Records. Due to his UK exposure, the song reached the top twenty there but only climbed to number 82 in his native country.[75] Later in the year, he signed with Vee-Jay Records, then on its dying legs, to release his "comeback" album, Little Richard Is Back. Due to the arrival of the Beatles and other British bands as well as the rise of soul labels such as Motown and Stax Records and the popularity of James Brown, Penniman's new releases were not well promoted or well received by radio stations . In November, 1964, Jimi Hendrix joined Penniman's Upsetters band as a full member.[76][77] In the Spring of 1965, Penniman took Hendrix and Billy Preston to a New York studio where they recorded the Don Covay soul ballad, "I Don't Know What You've Got (But It's Got Me)", which became a number 12 R&B hit.[78][nb 1]

Hendrix and Penniman clashed over the spotlight, Hendrix's tardiness, wardrobe and Hendrix's stage antics. Hendrix also complained over not being properly paid by Penniman. In July 1965, Richard's Brother Charles fired Jimi [This is possibly incorrect. Jimi wrote to his father, Al Hendrix, that he quit Little Richard over money problems - he was owned 1,000 dollars.] Hendrix's then rejoined The Isley Brothers' band, the IB Specials.[80] Penniman later signed with Modern Records, releasing a modest charter, "Do You Feel It?" before leaving for Okeh Records in early 1966. Two poorly produced albums were released over time, first a live album, cut at the Domino, in Atlanta, Georgia. Okeh paired Penniman with his old friend, Larry Williams, who produced two albums on Penniman, including the studio release, The Explosive Little Richard, which produced the modest charters "Poor Dog" and "Commandments of Love". His second Okeh album, Little Richard's Greatest Hits Recorded Live!, returned him to the album charts.[81][82][83] In 1967, Penniman signed with Brunswick Records but after clashing with the label over musical direction, he left the label that same year.

Penniman felt that producers on his labels worked in not promoting his records during this period. Later, he claimed they kept trying to push him to records similar to Motown and felt he wasn't treated with appropriate respect.[84] Little Richard often performed in dingy clubs and lounges with little support from his label. While Penniman managed to perform in huge venues overseas such as England and France, Penniman was forced to perform in the Chitlin' Circuit. Penniman's flamboyant look, while a hit during the 1950s, failed to help his labels to promote him to more conservative black record buyers.[85] Penniman later claimed that his decision to "backslide" from his ministry, led religious clergymen to protest his new recordings.[86] Making matters worse, Penniman said, was his insistence on performing in front of integrated audiences at the time of the black liberation movement shortly after the Watts riots and the formation of the Black Panthers prevented many black radio disk jockeys in certain areas of the country, including Los Angeles, to play his music.[87] Now acting as his manager, Larry Williams convinced Penniman to focus on his live shows. By 1968, he had ditched the Upsetters for his new backup band, the Crown Jewels, performing on the Canadian TV show, "Where It's At". Penniman was also featured on the Monkees TV special 33⅓ Revolutions per Monkee in April 1969. Williams booked Penniman shows in Las Vegas casinos and resorts, leading Penniman to adapt a wilder flamboyant and androgynous look, inspired by the success of his former backing guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Penniman was soon booked at rock festivals such as the Atlantic City Pop Festival where he stole the show from headliner Janis Joplin. Penniman produced a similar show stealer at the Toronto Pop Festival with John Lennon as the headliner. These successes brought Little Richard to talk shows such as the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and the Dick Cavett Show, making him a major celebrity again.[88]

Responding to his reputation as a successful concert performer, Reprise Records signed Penniman in 1970 where he released the album, The Rill Thing, with the philosophical single, "Freedom Blues", becoming his biggest charted single in years. In May 1970, Penniman made the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. Despite the success of "Freedom Blues", none of Penniman's other Reprise singles charted with the exception of "Greenwood, Mississippi", a swamp rock original by guitar hero, Travis Wammack, who incidentally played on the track. It charted only briefly on the Billboard Hot 100 and Cash Box pop chart, also on the Billboard Country charts; made a strong showing on WWRL in New York, before disappearing. Penniman became a featured guest instrumentalist and vocalist on recordings by acts such as Delaney and Bonnie, Joey Covington and Joe Walsh and was prominently featured on Canned Heat's 1972 hit single, "Rockin' with the King". To keep up with his finances and bookings, Penniman and three of his brothers formed a management company, Bud Hole Incorporated.[89] By 1972, Penniman had entered the rock and roll revival circuit, and that year, he co-headlined the London Rock and Roll Show at Wembley Stadium with fellow peer Chuck Berry where he'd come onstage and announce himself "the king of rock and roll", fittingly also the title of his 1971 album with Reprise and told the packed audience there to "let it all hang out"; Penniman however was booed during the show when he climbed on top of his piano and stopped singing; he also seemed to ignore much of the crowd. To make matters worse, he showed up with just five musicians, and struggled through low lighting and bad microphones. When the concert film documenting the show came out, his performance was considered generally strong, though his fans noticed a drop in energy and vocal artistry. Two songs he performed did not make the final cut of the film. The following year, he recorded a charting soul ballad, "In the Middle of the Night", released with proceeds donated to victims of tornadoes that had caused damage in 12 states.[90] In 1976, Penniman re-recorded eighteen of his classic rock and roll hits in Nashville for K-Tel Records, in high tech stereo recreations, with a single featuring live versions of "Good Golly Miss Molly" and "Rip It Up" reaching the UK singles chart.[91] Penniman's performances began to take a toll by 1973, however, suffering from voice problems and quirky marathon renditions. Penniman later admitted that he was heavily addicted to drugs and alcohol at the time. By 1977, worn out from years of abuse and wild partying as well as a string of personal tragedies, Penniman quit rock and roll again and returned to evangelism, releasing one gospel album, God's Beautiful City, in 1979.[92]

Comeback (1984–1999)

In 1984, Penniman filed a $112 million lawsuit against Specialty Records; Art Rupe and his publishing company, Venice Music; and ATV Music for not paying royalties to him after he left the label in 1959.[93] The suit was settled out of court in 1986.[94] According to some reports, Michael Jackson allegedly gave him monetary compensation for his work when he co-owned (with Sony-ATV) songs by the Beatles and Little Richard.[95] In 1985, Charles White released the singer's authorized biography, Quasar of Rock: The Life and Times of Little Richard, which returned Penniman to the spotlight.[96] Penniman returned to show business in what Rolling Stone would refer to as a "formidable comeback" following the book's release.[96]

Reconciling his roles as evangelist and rock and roll musician for the first time, Penniman stated that the genre could be used for good or evil.[97] After accepting a role in the film Down and Out in Beverly Hills, Little Richard and Billy Preston penned the faith-based rock and roll song "Great Gosh A'Mighty" for its soundtrack.[97] Little Richard won critical acclaim for his film role, and the song found success on the American and British charts.[97] The hit led to the release of the album Lifetime Friend (1986) on Warner Bros. Records, with songs deemed "messages in rhythm", including a gospel rap track.[98] In addition to a version of "Great Gosh A'Mighty", cut in England, the album featured two singles that charted in the UK, "Somebody's Comin'" and "Operator". Penniman spent much of the rest of the decade as a guest on TV shows and appearing in films, winning new fans with what was referred to as his "unique comedic timing".[99] In 1989, Penniman provided rhythmic preaching and background vocals on the extended live version of the U2–B.B. King hit "When Love Comes to Town". That same year, Little Richard returned to singing his classic hits following a performance of "Lucille" at an AIDS benefit concert.[100]

In 1990, Penniman contributed a spoken-word rap on Living Colour's hit song, "Elvis Is Dead", from their album Time's Up. [101][102] That same year he appeared in a cameo for the music video of Cinderella's "Shelter Me". The following year, he was one of the featured performers on the hit single and video "Voices That Care" that was produced to help boost the morale of US troops involved in Operation Desert Storm. He also recorded a rock and roll version of "The Itsy Bitsy Spider" that year that led to a deal with Disney Records, resulting in the release of a hit 1992 children's album, Shake It All About.

In 1994, Penniman sang the theme song to the award-winning PBS Kids and TLC animated television series The Magic School Bus based on the book series created by Joanna Cole and Bruce Degen and published by Scholastic Corporation. He also opened Wrestlemania X from Madison Square Garden on March 20 that year miming to his re worked rendition of "America the Beautiful".

Throughout the 1990s, Penniman performed around the world and appeared on TV, film, and tracks with other artists, including Jon Bon Jovi, Elton John and Solomon Burke. In 1992 he released his final album, Little Richard Meets Masayoshi Takanaka featuring members of Richard's then current touring band.[103]

Later years (2000–present)

In 2000, Penniman's life was dramatized for the biographical film Little Richard, which focused on his early years, including his heyday, his religious conversion and his return to secular music in the early 1960s. Penniman was played by Leon, who earned an NAACP Image Award nomination for his performance in this role. In 2002, Penniman contributed to the Johnny Cash tribute album, Kindred Spirits: A Tribute to the Songs of Johnny Cash. In 2004-2005, he released two sets of unreleased and rare cuts, from the Okeh label 1966/67 and the Reprise label 1970/72. Included was the full “Southern Child” album, produced and composed mostly by Richard, scheduled for release in 1972, but shelved. 2006, Little Richard was featured in a popular advertisement for the GEICO brand.[104] A 2005 recording of his duet vocals with Jerry Lee Lewis on a cover of the Beatles' "I Saw Her Standing There" was included on Lewis's 2006 album, Last Man Standing. The same year, Penniman was a guest judge on the TV series Celebrity Duets. Penniman and Lewis performed alongside John Fogerty at the 2008 Grammy Awards in a tribute to the two artists considered to be cornerstones of rock and roll by the NARAS. That same year, Penniman appeared on radio host Don Imus' benefit album for sick children, The Imus Ranch Record.[105] In June 2010, Little Richard recorded a gospel track for an upcoming tribute album to songwriting legend Dottie Rambo. In 2009, Penniman was Inducted into The Louisiana Music Hall Of Fame in a concert in New Orleans, attended by Fats Domino.

Throughout the first decade of the new millennium, Penniman kept up a stringent touring schedule, performing primarily in the United States and Europe. However, sciatic nerve pain in his left leg and then replacement of the involved hip began affecting the frequency of his performances by 2010. Despite his health problems, Penniman continued to perform to receptive audiences and critics. Rolling Stone reported that at a performance at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C., in June 2012, Penniman was "still full of fire, still a master showman, his voice still loaded with deep gospel and raunchy power."[106] Little Richard performed a full 90-minute show at the Pensacola Interstate Fair in Pensacola, Florida, in October 2012, at the age of 79, and headlined at the Orleans Hotel in Las Vegas during Viva Las Vegas Rockabilly Weekend in March 2013.[107][108] In September 2013, Rolling Stone published an interview with Penniman who admitted that he would be retiring from performing. "I am done, in a sense, because I don't feel like doing anything right now." He told in the magazine adding, "I think my legacy should be that when I started in showbusiness there wasn't no such thing as rock'n'roll. When I started with 'Tutti Frutti', that's when rock really started rocking." [109]

In 2014, actor Brandon Mychal Smith received critical acclaim for his portrayal of Penniman in the James Brown biographical drama film Get on Up.[110][111][112] Mick Jagger co-produced the motion picture.[113][114] In June 2015, Penniman appeared before a paying audience, clad in sparkly boots and a brightly colored jacket at the Wildhorse Saloon in Nashville to receive the Rhapsody & Rhythm Award from and raise funds for the National Museum of African American Music. It was reported that he charmed the crowd by reminiscing about his early days working in Nashville nightclubs.[115][116] In May 2016, the National Museum of African American Music issued a press release indicating that Penniman was one of the key artists and music industry leaders that attended its 3rd annual Celebration of Legends Luncheon in Nashville honoring Shirley Caesar, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff with Rhapsody & Rhythm Awards.[117] In 2016, a new CD was released on Hitman Records, California (I'm Comin') with released and previously unreleased material from the 1970s, including an a cappella version of his 1975 single release, "Try To Help Your Brother". On September 6, 2017, Penniman participated in a long television interview, for the Christian Three Angels Broadcasting Network, dressed conservatively and unrecognizable from his stage persona.[citation needed]

Personal life

Relationships and family

Around 1956, Penniman became involved with Audrey Robinson, a 16-year-old college student, originally from Savannah, Georgia.[100][118] Penniman and Robinson quickly got acquainted despite Robinson not being a fan of rock and roll music. Penniman claimed in his 1984 autobiography that he invited other men to have sexual encounters with her in groups and claimed to have once invited Buddy Holly to have sex with her; Robinson denied those claims.[100][119] Penniman proposed marriage to Robinson shortly before he converted but Robinson refused. Robinson later became known under the name Lee Angel and became a stripper and socialite.[120] She reconnected with Penniman in the 1960s though Robinson left him again after Penniman's drug abuse worsened, before reuniting for good in the 1980s.[100] Robinson was interviewed for Penniman's 1985 BBC documentary on the South Bank Show and denied Penniman's claims as they went back and forth. According to Robinson, Penniman would use her to buy food in white-only fast food stores as he could not enter any due to the color of his skin. Robinson was black, but had a very light complexion.

Penniman met his only wife, Ernestine Harvin, at an evangelical rally in October 1957. They began dating that year and wed on July 12, 1959, in California. According to Harvin, she and Little Richard initially enjoyed a happy marriage with "normal" sexual relations. Harvin claimed when the marriage ended in divorce in 1964, it was due to her husband's celebrity status, noting that it had made life difficult for her. Penniman would claim the marriage fell apart due to his being a neglectful husband and his sexuality.[121] Both Robinson and Harvin denied Penniman's claims that he was gay and Penniman believed they did not know it because he was "such a pumper in those days".[121] During the marriage, Penniman and Harvin adopted a one-year-old boy, Danny Jones, from a late church associate.[100] Little Richard and his son remain close, with Jones often acting as one of his bodyguards.[122] Ernestine later married Mcdonald Campbell in Santa Barbara, California, on March 23, 1975.

Sexuality

Penniman said in 1984 that he played with just girls as a child and was subjected to homophobic jokes and ridicule because of his manner of walk and talk.[123] His father brutally punished him whenever he caught his son wearing his mother's makeup and clothing [124] The singer claimed to have been sexually involved with both sexes as a teenager.[125] Because of his effeminate mannerisms, his father kicked him out of their family home at 15.[5] In 1985, on The South Bank Show, Penniman explained, "my daddy put me out of the house. He said he wanted seven boys, and I had spoiled it, because I was gay."[100]

Penniman first got involved in voyeurism in his early twenties, when a female friend would drive him around and pick up men who would allow him to watch them have sex in the backseat of cars. Penniman's activity caught the attention of Macon police in 1955 and he was arrested after a gas station attendant in Macon reported sexual activity in a car Penniman was occupying with a heterosexual couple. Cited on a sexual misconduct charge, he spent three days in jail and was temporarily banned from performing in Macon, Georgia.[126]

In the early 1950s, he became acquainted with openly gay musician Billy Wright, who helped in establishing Penniman's look, advising him to use pancake makeup on his face and wear his hair in a long-haired pompadour style similar to his.[27] As Penniman got used to the makeup, he ordered his band, the Upsetters, to wear the makeup too, to gain entry into predominantly white venues during performances, later stating, "I wore the make-up so that white men wouldn't think I was after the white girls. It made things easier for me, plus it was colorful too."[127] In 2000, Richard told Jet magazine, "I figure if being called a sissy would make me famous, let them say what they want to."[128] Penniman's look, however, still attracted female audiences, who would send him naked photos and their phone numbers.[129][130] Groupies began throwing undergarments at Penniman during performances.

During Penniman's heyday, his obsession with voyeurism carried on with his girlfriend Audrey Robinson. Penniman later wrote that Robinson would have sex with men while she sexually stimulated Penniman.[129] Despite claiming to be born again after leaving rock and roll for the church in 1957, Penniman left Oakwood College after exposing himself to a male student. After the incident was reported to the student's father, Penniman withdrew from the college.[131] In 1962, Penniman was arrested for spying on men urinating in toilets at a Trailways bus station in Long Beach, California.[132] Audrey Robinson disputed Penniman's claims of homosexuality in 1985. After re-embracing rock and roll in the mid-1960s, he began participating in orgies and continued to be a voyeur. In his 1984 book, while demeaning homosexuality as "unnatural" and "contagious", he told Charles White he was "omnisexual".[100] In 1995, Little Richard told Penthouse that he always knew he was gay, saying "I've been gay all my life".[100] In 2007, Mojo Magazine referred to Little Richard as "bisexual".[133] In October 2017, Penniman once again denounced homosexuality in an interview with Three Angels Broadcasting Network, calling homosexual and transgender identity "unnatural affection" that goes against "the way God wants you to live".[134]

Drug use

During his initial heyday in the 1950s rock and roll scene, Penniman was a teetotaler abstaining from alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs. Penniman often fined bandmates for drug and alcohol use during this era. By the mid-1960s, however, Penniman began drinking heavy amounts of alcohol and smoking cigarettes and marijuana.[135] By 1972, he had developed an addiction to cocaine. He later lamented during that period, "They should have called me Lil Cocaine, I was sniffing so much of that stuff!"[136] By 1975, he had developed addictions to both heroin and PCP, otherwise known as "angel dust". His drug and alcohol use began to affect his professional career and personal life. "I lost my reasoning," he would later recall.[137]

He said of his cocaine addiction that he did whatever he could to use cocaine.[138] Penniman admitted that his addictions to cocaine, PCP and heroin were costing him as much as $1,000 a day.[139] In 1977, longtime friend Larry Williams once showed up with a gun and threatened to kill him for failing to pay his drug debt. Penniman later mentioned that this was the most fearful moment of his life because Williams's own drug addiction made him wildly unpredictable. Penniman did, however, also acknowledge that he and Williams were "very close friends" and when reminiscing of the drug-fueled clash, he recalled thinking "I knew he loved me – I hoped he did!"[140] Within that same year, Penniman had several devastating personal experiences, including his brother Tony's death of a heart attack, the accidental shooting of his nephew that he loved like a son, and the murder of two close personal friends – one a valet at "the heroin man's house."[139] The combination of these experiences convinced the singer to give up drugs including alcohol, along with rock and roll, and return to the ministry.[141]

Religion

Penniman's family had deep evangelical (Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME)) Christian roots, including two uncles and a grandfather who were preachers.[14] He also took part in Macon's Pentecostal churches, which were his favorites mainly due to their music, charismatic praise, dancing in the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues.[11] At age 10, influenced by Pentecostalism, Little Richard would go around saying he was a faith healer, singing gospel music to people who were feeling sick and touching them. He later recalled that they would often indicate that they felt better after he prayed for them and would sometimes give him money.[11] Little Richard had aspirations of being a preacher due to the influence of singing evangelist Brother Joe May.[14]

After he was born again in 1957, Penniman enrolled at Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama, a mostly black Seventh-day Adventist college, to study theology. Little Richard returned to secular music in the early 1960s.[142] He was eventually ordained a minister in 1970 and resumed evangelical activities in 1977. Penniman represented Memorial Bibles International and sold their Black Heritage Bible, which highlighted the Book's many black characters. As a preacher, he evangelized in small churches and packed auditoriums of 20,000 or more. His preaching focused on uniting the races and bringing lost souls to repentance through God's love.[143] In 1984, Penniman's mother, Leva Mae, died following a period of illness. Only a few months prior to her death, Penniman promised her that he would remain a Christian.[97]

During the 1980s and 1990s, Penniman officiated at celebrity weddings. In 2006, Little Richard wedded twenty couples who won a contest in one ceremony.[144] The musician used his experience and knowledge as a minister and elder statesman of rock and roll to preach at funerals of musical friends such as Wilson Pickett and Ike Turner.[145] At a benefit concert in 2009 to raise funds to help rebuild children's playgrounds destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, Penniman asked guest of honor Fats Domino to pray with him and others. His assistants handed out inspirational booklets at the concert, which was a common practice at Penniman's shows.[146] Penniman told a Howard Theatre, Washington, D.C. audience in June 2012, "I know this is not Church, but get close to the Lord. The world is getting close to the end. Get close to the Lord."[106] In 2013, Penniman elaborated on his spiritual philosophies, stating "God talked to me the other night. He said He's getting ready to come. The world's getting ready to end and He's coming, wrapped in flames of fire with a rainbow around his throne." Rolling Stone reported his apocalyptic prophesies generated snickers from some audience members as well as cheers of support. Penniman responded to the laughter by stating: "When I talk to you about [Jesus], I'm not playing. I'm almost 81 years old. Without God, I wouldn't be here."[147]

In 2017, he came back to the Seventh-day Adventist Church and was rebaptized. 3ABN interviewed Penniman, and later he shared his personal testimony at 3ABN Fall Camp Meeting 2017.[148][149][150]

Health problems

In October 1985, Penniman returned to the United States from England, where he had finished recording his album Lifetime Friend, to film a guest spot on the show, Miami Vice. Following the taping, he accidentally crashed his sports car into a telephone pole in West Hollywood, California. He suffered a broken right leg, broken ribs and head and facial injuries.[151] His recovery from the accident took several months.[151] His accident prevented him from being able to attend the inaugural Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony in January 1986 where he was one of several inductees. He instead supplied a recorded message.[81]

In 2007, Little Richard began having problems walking due to sciatica in his left leg, requiring him to use crutches.[152][153] In November 2009, he entered a hospital to have replacement surgery on his left hip. Despite returning to performance the following year, Penniman's problems with his hip continued and he has since been brought onstage by wheelchair. He has told fans that his surgery has his hip "breaking inside" and refuses to have further work on it.[citation needed] On September 30, 2013, he revealed to CeeLo Green at a Recording Academy fundraiser that he had suffered a heart attack at his home the week prior and stated he used aspirin and had his son turn the air conditioner on, which his doctor confirmed had saved his life. Little Richard stated, "Jesus had something for me. He brought me through".[147]

On April 28, 2016, Little Richard's friend, Bootsy Collins, stated on his Facebook page that, "he is not in the best of health so I ask all the Funkateers to lift him up." Reports subsequently began being published on the internet stating that Little Richard was in grave health and that his family were gathering at his bedside. On May 3, 2016, Rolling Stone reported that Little Richard and his lawyer provided a health information update in which Richard stated, "not only is my family not gathering around me because I'm ill, but I'm still singing. I don't perform like I used to, but I have my singing voice, I walk around, I had hip surgery a while ago but I'm healthy.'" His lawyer also reported: "He's 83. I don't know how many 83-year-olds still get up and rock it out every week, but in light of the rumors, I wanted to tell you that he's vivacious and conversant about a ton of different things and he's still very active in a daily routine."[154] Penniman is now wheelchair bound after his failed hip surgery and after injuries from a fall.[citation needed]

Legacy

Music

He claims to be "the architect of rock and roll", and history would seem to bear out Little Richard's boast. More than any other performer – save, perhaps, Elvis Presley, Little Richard blew the lid off the Fifties, laying the foundation for rock and roll with his explosive music and charismatic persona. On record, he made spine-tingling rock and roll. His frantically charged piano playing and raspy, shouted vocals on such classics as "Tutti Frutti", "Long Tall Sally" and "Good Golly, Miss Molly" defined the dynamic sound of rock and roll.

—Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[81]

Penniman's music and performance style had a pivotal effect on the shape of the sound and style of popular music genres of the 20th century.[31][39][155] As a rock and roll pioneer, Penniman embodied its spirit more flamboyantly than any other performer.[156] Penniman's raspy shouting style gave the genre one of its most identifiable and influential vocal sounds and his fusion of boogie-woogie, New Orleans R&B and gospel music blazed its rhythmic trail.[156][157]

Combining elements of boogie, gospel, and blues, Little Richard introduced several of rock music's most characteristic musical features, including its loud volume and vocal style emphasizing power, and its distinctive beat and rhythm. He departed from boogie-woogie's shuffle rhythm and introduced a new distinctive rock beat, where the beat division is even at all tempos. He reinforced the new rock rhythm with a two-handed approach, playing patterns with his right hand, with the rhythm typically popping out in the piano's high register. His new rhythm, which he introduced with "Tutti Frutti" (1955), became the basis for the standard rock beat, which was later consolidated by Chuck Berry.[158] "Lucille" (1957) foreshadowed the rhythmic feel of 1960s classic rock in several ways, including its heavy bassline, slower tempo, strong rock beat played by the entire band, and verse–chorus form similar to blues.[159]

Penniman's voice was able to generate croons, wails, and screams unprecedented in popular music.[31] He was cited by two of soul music's pioneers, Otis Redding and Sam Cooke, as contributing to that genre's early development. Redding stated that most of his music was patterned after Penniman's, referring to his 1953 recording "Directly From My Heart To You" as the personification of soul, and that he had "done a lot for [him] and [his] soul brothers in the music business."[160] Cooke said in 1962 that Penniman had done "so much for our music".[161] Cooke had a top 40 hit in 1963 with his cover of Penniman's 1956 hit "Send Me Some Loving".[162]

James Brown and others credited Little Richard and his mid-1950s backing band, The Upsetters, with having been the first to put the funk in the rock beat. This innovation sparked the transition from 1950s rock and roll to 1960s funk[163][164][165]

Penniman's hits of the mid-1950s, such as "Tutti Frutti", "Long Tall Sally", "Keep A-Knockin'" and "Good Golly Miss Molly", were generally characterized by playful lyrics with sexually suggestive connotations.[31] AllMusic writer Richie Unterberger stated that Little Richard "merged the fire of gospel with New Orleans R&B, pounding the piano and wailing with gleeful abandon", and that while "other R&B greats of the early 1950s had been moving in a similar direction, none of them matched the sheer electricity of Richard's vocals. With his high-speed deliveries, ecstatic trills, and the overjoyed force of personality in his singing, he was crucial in upping the voltage from high-powered R&B into the similar, yet different, guise of rock and roll."[39] Due to his innovative music and style, he's often widely acknowledged as the "architect of rock and roll".[81]

Ray Charles introduced him at a concert in 1988 as "a man that started a kind of music that set the pace for a lot of what's happening today."[166] Rock and roll pioneer Bo Diddley called Penniman "one of a kind" and "a show business genius" that "influenced so many in the music business".[161] Penniman's contemporaries, including Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Bill Haley, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Everly Brothers, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, all recorded covers of his works.[167] Taken by his music and style, and personally covering four of Little Richard's tunes on his own two breakthrough albums in 1956, Presley told Little Richard in 1969 that his music was an inspiration to him and that he was "the greatest".[168] Pat Boone noted in 1984, "no one person has been more imitated than Little Richard".[160] As they wrote about him for their Man of the Year – Legend category in 2010, GQ magazine stated that Little Richard "is, without question, the boldest and most influential of the founding fathers of rock'n'roll".[100] R&B pioneer Johnny Otis stated that "Little Richard is twice as valid artistically and important historically as Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones put together."[161]

Society

In addition to his musical style, Penniman was cited as one of the first crossover black artists, reaching audiences of all races. His music and concerts broke the color line,[169] drawing blacks and whites together despite attempts to sustain segregation. As H.B. Barnum explained in Quasar of Rock, Little Richard "opened the door. He brought the races together." [170] Barnum described Little Richard's music as not being "boy-meets-girl-girl-meets-boy things, they were fun records, all fun. And they had a lot to say sociologically in our country and the world."[48] Barnum also stated that Penniman's "charisma was a whole new thing to the music business", explaining that "he would burst onto the stage from anywhere, and you wouldn't be able to hear anything but the roar of the audience. He might come out and walk on the piano. He might go out into the audience." Barnum also stated that Penniman was innovative in that he would wear colorful capes, blouse shirts, makeup and suits studded with multi-colored precious stones and sequins, and that he also brought flickering stage lighting from his show business experience into performance venues where rock and roll artists performed.[171] In 2015, the National Museum of African American Music honored Penniman for helping to shatter the color line on the music charts changing American culture forever.[116][169]

"Little Richard was always my main man. How hard must it have been for him: gay, black and singing in the South? But his records are a joyous good time from beginning to end." – Lemmy, Motörhead[172]

Influence

Penniman influenced generations of performers across musical genres.[50] James Brown and Otis Redding both idolized him.[160][173] Brown allegedly came up with the Famous Flames debut hit, "Please, Please, Please", after Richard had written the words on a napkin.[174][175] Redding started his professional career with Little Richard's band, The Upsetters.[176] He first entered a talent show performing Penniman's "Heeby Jeebies", winning for 15 consecutive weeks.[177] Ike Turner claimed most of Tina Turner's early vocal delivery was based on Little Richard, something Penniman himself reiterated in the introduction of Turner's biography, Takin' Back My Name.[178] Bob Dylan first performed covers of Penniman's songs on piano in high school with his rock and roll group, the Golden Chords; in 1959 when leaving school, he wrote in his yearbook under "Ambition": "to join Little Richard".[179] Jimi Hendrix was influenced in appearance (clothing and hairstyle/mustache) and sound by Penniman. He was quoted in 1966 saying, "I want to do with my guitar what Little Richard does with his voice."[180] Others influenced by Penniman early on in their lives included Bob Seger and John Fogerty.[181][182] Michael Jackson admitted that Penniman had been a huge influence on him prior to the release of Off the Wall.[183] Rock critics noted similarities between Prince's androgynous look, music and vocal style to Little Richard's.[184][185][186]

The origins of Cliff Richard's name change from Harry Webb was seen as a partial tribute to his musical hero Little Richard and singer Rick Richards.[187] Several members of The Beatles were heavily influenced by Penniman, including Paul McCartney and George Harrison. McCartney idolized him in school and later used his recordings as inspiration for his uptempo rockers, such as "I'm Down.".[188][incomplete short citation][189] "Long Tall Sally" was the first song McCartney performed in public.[190] McCartney would later state, "I could do Little Richard's voice, which is a wild, hoarse, screaming thing. It's like an out-of-body experience. You have to leave your current sensibilities and go about a foot above your head to sing it."[191] During the Beatles' Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, Harrison commented, "thank you all very much, especially the rock 'n' rollers, an' Little Richard there, if it wasn't for (gesturing to Little Richard), it was all his fault, really."[192] Upon hearing "Long Tall Sally" in 1956, John Lennon later commented that he was so impressed that he "couldn't speak".[193] Rolling Stones members Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were also profoundly influenced by Little Richard, with Jagger citing him as his introduction to R&B music and referring to him as "the originator and my first idol".[69] Penniman was an early vocal influence on Rod Stewart.[194] David Bowie called Little Richard his "inspiration" stating upon listening to "Tutti Frutti" that he "heard God".[195][196]

After opening for him with his band Bluesology, pianist Reginald Dwight was inspired to be a "rock and roll piano player", later changing his name to Elton John.[197] Farrokh Bulsara performed covers of Little Richard's songs as a teen, before finding fame as Freddie Mercury, frontman for Queen.[198] Lou Reed referred to Penniman as his "rock and roll hero", deriving inspiration from "the soulful, primal force" of the sound Penniman and his saxophonist made on "Long Tall Sally." Reed later stated, "I don't know why and I don't care, but I wanted to go to wherever that sound was and make a life."[199] Patti Smith said, "To me, Little Richard was a person that was able to focus a certain physical, anarchistic, and spiritual energy into a form which we call rock 'n' roll ... I understood it as something that had to do with my future. When I was a little girl, Santa Claus didn't turn me on. Easter Bunny didn't turn me on. God turned me on. Little Richard turned me on."[200] The music of Deep Purple and Motörhead was also heavily influenced by Little Richard, as well as that of AC/DC.[201][202] The latter's early lead vocalist and co-songwriter Bon Scott idolized Little Richard and aspired to sing like him, its lead guitarist and co-songwriter Angus Young was first inspired to play guitar after listening to Penniman's music, and rhythm guitarist and co-writer Malcolm Young derived his signature sound from playing his guitar like Penniman's piano.[203][204][205][206][201][202] Later performers such as Mystikal, André "André 3000" Benjamin of Outkast and Bruno Mars were cited by critics as having emulated Penniman's style in their own works. Mystikal's rap vocal delivery was compared to Penniman's.[207] André 3000's vocals in Outkast's hit, "Hey Ya!", were compared to an "indie rock Little Richard".[208] Bruno Mars admitted Little Richard was one of his earliest influences.[209] Mars' song, "Runaway Baby" from his album, Doo-Wops & Hooligans was cited by The New York Times as "channeling Little Richard".[210] Prior to his passing in 2017, Audioslave's and Soundgarden's frontman Chris Cornell traced his musical influences back to Penniman via The Beatles.[211]

Awards and honors

Penniman received the Cashbox Triple Crown Award for "Long Tall Sally" in 1956.[212] In 1984, he was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. He was inducted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, being a member of the initial class of inductees chosen for that honor.[81] In 1990, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1994.[213] In 1993, he received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[214] In 1997, he was given the American Music Award of Merit.[215] In 2002, along with Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, Little Richard was honored as one of the first group of BMI icons at the 50th Annual BMI Pop Awards.[216] That same year, he was inducted into the NAACP Image Award Hall of Fame.[217] A year later, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2006, he was inducted into the Apollo Theater Hall of Fame.[218] Four years afterwards, he received a plaque on the theater's Walk of Fame.[219] In 2008, he received a star at Nashville's Music City Walk of Fame.[220] In 2009, he was inducted to the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.[221] The UK issue of GQ named him its Man of the Year in its Legend category in 2010.[100]

Penniman appeared in person to receive an honorary degree from his hometown's Mercer University on May 11, 2013.[222] The day before the doctorate of humanities degree was to be bestowed upon him, the mayor of Macon announced that one of Little Richard's childhood homes, an historic site, will be moved to a rejuvenated section of that city's Pleasant Hill district. It will be restored and named the Little Richard Penniman – Pleasant Hill Resource House, a meeting place where local history and artifacts will be displayed as provided by residents.[223][224][225] Penniman was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame on May 7, 2015.[226] On June 6, 2015, Penniman was inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Music Hall of Fame[227] On June 19, 2015, the National Museum of African American Music honored Penniman with the Rhapsody & Rhythm Award for his key role in the formation of popular music genres, influencing singers and musicians across genres from Rock to Hip-Hop, and helping to shatter the color line on the music charts changing American culture forever.[116][169]

In 2010, Time Magazine listed Here's Little Richard as one of the 100 Greatest and Most Influential Albums of All Time.[56] Included in numerous Rolling Stone listed his Here's Little Richard at number fifty on the magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[228] He was ranked eighth on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[229] Rolling Stone listed three of Little Richard's recordings, "The Girl Can't Help It", "Long Tall Sally" and "Tutti Frutti", on their 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[230] Two of the latter songs and "Good Golly, Miss Molly" were listed on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.[231] The Grammy Hall of Fame inducted several of Little Richard's recordings including "Tutti Frutti", "Lucille", "Long Tall Sally" and Here's Little Richard.[232] In 2007, an eclectic panel of renowned recording artists voted "Tutti Frutti" number one on Mojo's The Top 100 Records That Changed The World, hailing the recording as "the sound of the birth of rock and roll."[233][234] In April 2012, Rolling Stone magazine declared that the song "still has the most inspired rock lyric on record."[235] The same recording was inducted to the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry in 2010, with the library claiming the "unique vocalizing over the irresistible beat announced a new era in music".[236]

In early 2019, Maggie Gonzalez, a resident of Macon, Georgia, began an online campaign proposing that a statue of Little Richard be erected in downtown Macon, taking the place of a Confederate memorial that currently occupies the space. Georgia law forbids the tearing down of Confederate statues, though they can be relocated; Gonzalez has proposed that it could be moved to nearby Rose Hill Cemetery.[237]

Discography

- Studio albums

- Here's Little Richard (1957)

- Little Richard (1958)

- The Fabulous Little Richard (1958)

- Pray Along with Little Richard (1960)

- Pray Along with Little Richard (Vol 2) (1960)

- The King of the Gospel Singers (1962)

- Little Richard Is Back (And There's A Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On!) (1964)

- Little Richard's Greatest Hits (1965)

- The Incredible Little Richard Sings His Greatest Hits - Live! (1967)

- The Wild and Frantic Little Richard (1967)

- The Explosive Little Richard (1967)

- Little Richard's Greatest Hits: Recorded Live! (1967)

- The Rill Thing (1970)

- Mr. Big (1971)

- The King of Rock and Roll (1971)

- Friends from the Beginning – Little Richard and Jimi Hendrix (1972)

- Southern Child (1972) unreleased

- Second Coming (1972)

- Right Now! (1974)

- Talkin' 'bout Soul (1974)

- Little Richard Live (1976)

- God's Beautiful City (1979)

- Lifetime Friend (1986)

- Shake It All About (1992)

- Little Richard Meets Masayoshi Takanaka (1992)

Filmography

- The Girl Can't Help It[238] (1956), lip-syncing the title number (different version from record), "Ready Teddy" and "She's Got It"

- Don't Knock the Rock[238] (1956), lip-syncing "Long Tall Sally" and "Tutti Frutti"

- Mister Rock and Roll[238] (1957), lip-syncing "Lucille" and "Keep A-Knockin'", on original prints

- Catalina Caper[238] (aka Never Steal Anything Wet, 1967), Richard lip-syncs an original tune, "Scuba Party", still unreleased on record by 2019.

- Little Richard: Live at the Toronto Peace Festival[238] (1969) – released on DVD in 2009 by Shout! Factory

- The London Rock & Roll Show [238](1973), performing "Lucille", "Rip It Up", "Good Golly Miss Molly", "Tutti Frutti", "I Believe" [a capella, a few lines], and "Jenny Jenny"

- Jimi Hendrix[238] (1973)

- Down and Out in Beverly Hills[238] (1986), co-starred as Orvis Goodnight and performed the production number, "Great Gosh A-Mighty"

- Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll TV Documentary (1987)

- Goddess of Love Made For TV Movie (1988)

- Purple People Eater[238] (1988)

- Scenes from the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills (1989) (uncredited)

- Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventures (1990) (voice)

- Mother Goose Rock 'n' Rhyme (1990)

- Columbo - S10E3 "Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star" (1991) (Cameo)

- The Naked Truth[238] (1992)

- Sunset Heat[238] (aka Midnight Heat) (1992)

- James Brown: The Man, The Message, The Music TV Documentary (1992)

- "Martin" as the exterminator (1992)

- The Pickle[238] (1993)

- Last Action Hero[238] (1993)

- Full House (1994) (Cameo) - Episode: Too Little Richard Too Late

- Baywatch[238] (1995) as Maurice in Episode: The Runaways

- The Drew Carey Show (1997) (cameo) - Episode: Drewstock

- Why Do Fools Fall in Love (1998)

- Mystery Alaska (1999)

- The Trumpet of the Swan (2001) (voice)

- The Simpsons (2002) (voice)

Let the Good Times Roll (1973) featured performances and behind-the-scenes candid footage of Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Fats Domino, Bill Haley, the Five Satins, the Shirelles, Chubby Checker, and Danny and the Juniors.[239]

Notes

Citations

- ^ "Little Richard se retira a los 80 años" [Little Richard retires at 80]. Europa Press (in Spanish). September 3, 2013.

- ^ Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues - A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers. p. 275. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- ^ "2015 My Music Matters: A Celebration of Legends Luncheon". National Museum of African American Music. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Kirby 2009, p. 30.

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 21. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 3. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 4–5. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Otfinoski 2010, p. 144.

- ^ White 2003, p. 7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 6. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b c White 2003, pp. 16–17. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 7–9. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b c White 2003, p. 16. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 18. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 15–17. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Ryan 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Seibert, David. "Ballard-Hudson Senior High School". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 17. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Lauterbach 2011, p. 152.

- ^ Turner, Ike. (1999). Takin' Back My Name: The Confessions of Ike Turner. Cawthorne, Nigel. London: Virgin. pp. xi. ISBN 1852278501. OCLC 43321298.

- ^ a b White 2003, pp. 21–22. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 22: "It was the only song I knew that wasn't a church song". sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 22–25. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 22–23. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 24–25. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 25. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b c White 2003, p. 28. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 29. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 36–38. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b c d e Langdon C. Winner. "Little Richard (American musician)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ a b White 2003, pp. 38–39. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ "Grady Gaines". Allmusic. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ Jonny Whiteside, "Charles Connor: The Rock and Roll Original", LA Weekly, May 14, 2014.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 40–41. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Nite 1982, p. 390.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 44–47. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 55–56. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b c "Little Richard". Allmusic. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ White 2003, p. 264. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Du Noyer 2003, p. 14.

- ^ "Show 6 – Hail, Hail, Rock 'n' Roll: The rock revolution gets underway". Digital.library.unt.edu. March 16, 1969. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ White 2003, p. 58. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 74–75. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Pegg 2002, p. 50: "Although they still had the audiences together in the building, they were there together. And most times, before the end of the night, they would be all mixed together".

- ^ White 2003, pp. 82–83. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Bayles 1996, p. 133: "He'd be on the stage, he'd be off the stage, he'd be jumping and yelling, screaming, whipping the audience on ...".

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 70. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 66. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b Myers, Marc (October 10, 2010). "Little Richard, The First". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ White 2003, p. 241. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 264–265. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ “12th Annual Cavalcade of Jazz starring Little Richard” Los Angeles Sentinel Aug. 9, 1956.

- ^ “Stars Galore Set for Sept. Jazz Festival” Article The California Eagle Aug. 23, 1956.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 82. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b Light, Alan (January 27, 2010). "Here's Little Richard | All-TIME 100 Albums | TIME.com". Entertainment.time.com. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b White 2003, pp. 89–92. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 91. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 92. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 95. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Miller 1996, p. 248.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 88–89. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 95–97. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 94–95. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 97. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 102: "Richard had such a unique voice and style that no one has ever matched it – even to this day". sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 103: "He sang gospel the way it should be sung. He had that primitive beat and sound that came so naturally ... the soul in his singing was not faked. It was real". sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 267. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ a b White 2003, p. 119. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 112. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Steen, Håkan (March 26, 2018). "Håkan Steen: Tack så mycket för liret "Jerka"" [Håkan Steen: Thanks so much for the jive "Jenka"]. Aftonbladet. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Harry 2000, p. 600.

- ^ White 2003, p. 121. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 248. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Havers, Richard; Evans, Richard (2010). The Golden Age of Rock 'N' Roll. Chartwell Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-0785826255.

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 12: Hendrix recording with Little Richard; Shadwick 2003, pp. 56–57: "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)" recorded in New York City.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 56–60.

- ^ a b c d e "Little Richard". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 1986. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 253–255. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 268–269. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ "Religion and Rock and Roll", Joel Martin Show, WBAB 102.3 FM, NY. Guests: Harry Hepcat and Little Richard, August 16, 1981.

- ^ Gulla 2008, p. 41.

- ^ White 2003, p. 132. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 133. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Gulla 2008, pp. 41–42.

- ^ White 2003, p. 168. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ "New York Beat". Jet. Vol. 44, no. 15. July 5, 1973. p. 62.

- ^ Betts, Graham (2004). Complete UK Hit Singles 1952–2004 (1st ed.). London: Collins. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-00-717931-2.

- ^ White 2003, p. 201. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Ocala Star-Banner 1984, p. 2.

- ^ "Inside Track". Billboard. Vol. 98, no. 20. May 17, 1986. p. 84.

- ^ "Michael Jackson's mom played role in business – Entertainment – Celebrities". August 5, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Rolling Stone 2013.

- ^ a b c d White 2003, p. 221. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, p. 273. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ Little Richard at IMDb

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chalmers 2012.

- ^ Mahon 2004, p. 151.

- ^ Rodman 1996, p. 46.

- ^ "Little Richard denies claims of poor health". Guardian. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Unlikely Titan of Advertising". CBS News. February 14, 2007.

- ^ "Singers Aid a Charity and The Man Who Runs It". September 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Patrick Doyle (June 17, 2012). "Little Richard Tears Through Raucous Set in Washington, D.C. | Music News". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ "Little Richard in concert". GoPensacola.com. October 28, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Photos: Little Richard headlines at Viva Las Vegas Rockabilly Weekend at The Orleans". Las Vegas Sun. April 1, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ [1]

- ^ David Blaustein (August 1, 2014). "Will 'Get On Up' Make You Stand Up and Cheer?". ABC News.

- ^ Mark McCarver (August 1, 2014). "James Brown's biopic 'Get On Up' takes huge risks with mixed results". Baltimore Post-Examiner.

- ^ "These Are The Best Parts Of 'Get On Up'". The Huffington Post. August 1, 2014.

- ^ "Get on Up (2014)". IMDb. August 1, 2014.

- ^ Annette Witheridge (August 2, 2014). "My mate the sex machine: Mick Jagger on his movie about his 'inspiration' James Brown". Mirror.

- ^ "Nashville's African American Music Museum To Honor Little Richard, CeCe Winans : MusicRow – Nashville's Music Industry Publication – News, Songs From Music City". Musicrow.com. June 17, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Juli Thanki (June 19, 2015). "Little Richard, Cece Winans, more honored in Nashville". The Tennessean. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "NMAAM Hosted Successful 2016 My Music Matters™: A Celebration of Legends Luncheon". National Museum of African American Music. May 11, 2016. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ White 2003, pp. 70–74. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 84–85. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)

- ^ White 2003, pp. 99–101. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWhite2003 (help)