Bridgeport, Connecticut, Centennial half dollar

| Bridgeport, Connecticut, Centennial half dollar | |

|---|---|

Fruits of four different cultivars. Left to right: plantain, red banana, apple banana, and Cavendish banana | |

| Source plant(s) | Musa |

| Part(s) of plant | Fruit |

| Uses | Food |

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry[1] – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus Musa. In some countries, cooking bananas are called plantains, distinguishing them from dessert bananas. The fruit is variable in size, color, and firmness, but is usually elongated and curved, with soft flesh rich in starch covered with a peel, which may have a variety of colors when ripe. The fruits grow upward in clusters near the top of the plant. Almost all modern edible seedless (parthenocarp) cultivated bananas come from two wild species – Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana, or hybrids of them.

Musa species are native to tropical Indomalaya and Australia; they were probably domesticated in New Guinea. They are grown in 135 countries, primarily for their fruit, and to a lesser extent to make banana paper and textiles, while some are grown as ornamental plants. The world's largest producers of bananas in 2022 were India and China, which together accounted for approximately 26% of total production. Bananas are eaten raw or cooked in recipes varying from curries to banana chips, fritters, fruit preserves, or simply baked or steamed.

Worldwide, there is no sharp distinction between dessert "bananas" and cooking "plantains": this works well enough in the Americas and Europe, but it breaks down in Southeast Asia where many more kinds of bananas are grown and eaten. The term "banana" is applied also to other members of the genus Musa, such as the scarlet banana (Musa coccinea), the pink banana (Musa velutina), and the Fe'i bananas. Members of the genus Ensete, such as the snow banana (Ensete glaucum) and the economically important false banana (Ensete ventricosum) of Africa are sometimes included. Both genera are in the banana family, Musaceae.

Banana plantations are subject to damage by parasitic nematodes and insect pests, and to fungal and bacterial diseases, one of the most serious being Panama disease which is caused by a Fusarium fungus. This and black sigatoka threaten the production of Cavendish bananas, the main kind eaten in the Western world, which is a triploid Musa acuminata. Plant breeders are seeking new varieties, but these are difficult to breed given that commercial varieties are seedless. To enable future breeding, banana germplasm is conserved in multiple gene banks around the world.

Description

The banana plant is the largest herbaceous flowering plant.[2] All the above-ground parts of a banana plant grow from a structure called a corm.[3] Plants are normally tall and fairly sturdy with a treelike appearance, but what appears to be a trunk is actually a pseudostem composed of multiple leaf-stalks (petioles). Bananas grow in a wide variety of soils, as long as it is at least 60 centimetres (2.0 ft) deep, has good drainage and is not compacted.[4] They are among the fastest growing of all plants, with daily surface growth rates recorded from 1.4 square metres (15 sq ft) to 1.6 square metres (17 sq ft).[5][6]

The leaves of banana plants are composed of a stalk (petiole) and a blade (lamina). The base of the petiole widens to form a sheath; the tightly packed sheaths make up the pseudostem, which is all that supports the plant. The edges of the sheath meet when it is first produced, making it tubular. As new growth occurs in the centre of the pseudostem, the edges are forced apart.[3] Cultivated banana plants vary in height depending on the variety and growing conditions. Most are around 5 m (16 ft) tall, with a range from 'Dwarf Cavendish' plants at around 3 m (10 ft) to 'Gros Michel' at 7 m (23 ft) or more.[7] Leaves are spirally arranged and may grow 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) long and 60 cm (2.0 ft) wide.[1] When a banana plant is mature, the corm stops producing new leaves and begins to form a flower spike or inflorescence. A stem develops which grows up inside the pseudostem, carrying the immature inflorescence until eventually it emerges at the top.[3] Each pseudostem normally produces a single inflorescence, also known as the "banana heart". After fruiting, the pseudostem dies, but offshoots will normally have developed from the base, so that the plant as a whole is perennial.[8] The inflorescence contains many petal-like bracts between rows of flowers. The female flowers (which can develop into fruit) appear in rows further up the stem (closer to the leaves) from the rows of male flowers. The ovary is inferior, meaning that the tiny petals and other flower parts appear at the tip of the ovary.[9]

The banana fruits develop from the banana heart, in a large hanging cluster called a bunch, made up of around 9 tiers called hands, with up to 20 fruits to a hand. A bunch can weigh 22–65 kilograms (49–143 lb).[10]

The fruit has been described as a "leathery berry".[11] There is a protective outer layer (a peel or skin) with numerous long, thin strings (Vascular bundles), which run lengthwise between the skin and the edible inner portion. The inner part of the common yellow dessert variety can be split lengthwise into three sections that correspond to the inner portions of the three carpels by manually deforming the unopened fruit.[12] In cultivated varieties, the seeds are diminished nearly to non-existence; their remnants are tiny black specks inside the fruit.[13]

-

A corm, about 25 cm (10 in) across

-

Young plant

-

Female flowers have petals at the tip of the ovary

-

'Tree' showing fruit and inflorescence

-

Single row planting

-

Inflorescence, partially opened

Evolution

Phylogeny

A 2011 phylogenomic analysis using nuclear genes indicates the phylogeny of some representatives of the Musaceae family. Major edible kinds of banana are shown in boldface.[14]

| Musaceae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ‡ Many cultivated bananas are hybrids of M. acuminata x M. balbisiana (not shown in tree).[15]

Work by Li and colleagues in 2024 identifies three subspecies of M. acuminata, namely sspp. banksii, malaccensis, and zebrina, as contributing substantially to the Ban, Dh, and Ze subgenomes of triploid cultivated bananas respectively.[16]

Taxonomy

The genus Musa was created by Carl Linnaeus in 1753.[17] The name may be derived from Antonius Musa, physician to the Emperor Augustus, or Linnaeus may have adapted the Arabic word for banana, mauz.[18] The ultimate origin of musa may be in the Trans–New Guinea languages, which have words similar to "#muku"; from there the name was borrowed into the Austronesian languages and across Asia, accompanying the cultivation of the banana as it was brought to new areas, via the Dravidian languages of India, into Arabic as a Wanderwort.[19] The word "banana" is thought to be of West African origin, possibly from the Wolof word banaana, and passed into English via Spanish or Portuguese.[20]

Musa is the type genus in the family Musaceae. The APG III system assigns Musaceae to the order Zingiberales, part of the commelinid clade of the monocotyledonous flowering plants. Some 70 species of Musa were recognized by the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families as of January 2013[update];[17] several produce edible fruit, while others are cultivated as ornamentals.[21]

The classification of cultivated bananas has long been a problematic issue for taxonomists. Linnaeus originally placed bananas into two species based only on their uses as food: Musa sapientum for dessert bananas and Musa paradisiaca for plantains. More species names were added, but this approach proved to be inadequate for the number of cultivars in the primary center of diversity of the genus, Southeast Asia. Many of these cultivars were given names that were later discovered to be synonyms.[22]

In a series of papers published from 1947 onwards, Ernest Cheesman showed that Linnaeus's Musa sapientum and Musa paradisiaca were cultivars and descendants of two wild seed-producing species, Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana, both first described by Luigi Aloysius Colla.[23] Cheesman recommended the abolition of Linnaeus's species in favor of reclassifying bananas according to three morphologically distinct groups of cultivars – those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa balbisiana, those primarily exhibiting the botanical characteristics of Musa acuminata, and those with characteristics of both.[22] Researchers Norman Simmonds and Ken Shepherd proposed a genome-based nomenclature system in 1955. This system eliminated almost all the difficulties and inconsistencies of the earlier classification of bananas based on assigning scientific names to cultivated varieties. Despite this, the original names are still recognized by some authorities, leading to confusion.[23][24]

The accepted scientific names for most groups of cultivated bananas are Musa acuminata Colla and Musa balbisiana Colla for the ancestral species, and Musa × paradisiaca L. for the hybrid of the two.[15]

Informal classification

In regions such as North America and Europe, Musa fruits offered for sale can be divided into small sweet "bananas" eaten raw when ripe as a dessert, and large starchy "plantains" or cooking bananas, which do not have to be ripe. Linnaeus made this distinction when naming two "species" of Musa.[25] Members of the "plantain subgroup" of banana cultivars, most important as food in West Africa and Latin America, correspond to this description, having long pointed fruit. They are described by Ploetz et al. as "true" plantains, distinct from other cooking bananas.[26]

The cooking bananas of East Africa however belong to a different group, the East African Highland bananas.[7] Further, small farmers in Colombia grow a much wider range of cultivars than large commercial plantations do,[27] and in Southeast Asia—the center of diversity for bananas, both wild and cultivated—the distinction between "bananas" and "plantains" does not work. Many bananas are used both raw and cooked. There are starchy cooking bananas which are smaller than those eaten raw. The range of colors, sizes and shapes is far wider than in those grown or sold in Africa, Europe or the Americas.[25] Southeast Asian languages do not make the distinction between "bananas" and "plantains" that is made in English. Thus both Cavendish dessert bananas and Saba cooking bananas are called pisang in Malaysia and Indonesia, kluai in Thailand and chuối in Vietnam.[28] Fe'i bananas, grown and eaten in the islands of the Pacific, are derived from a different wild species. Most Fe'i bananas are cooked, but Karat bananas, which are short and squat with bright red skins, are eaten raw.[29]

History

Domestication

The earliest domestication of bananas (Musa spp.) was from naturally occurring parthenocarpic (seedless) individuals of Musa banksii in New Guinea.[30] These were cultivated by Papuans before the arrival of Austronesian-speakers. Numerous phytoliths of bananas have been recovered from the Kuk Swamp archaeological site and dated to around 10,000 to 6,500 BP.[31][32] Foraging humans in this area began domestication in the late Pleistocene using transplantation and early cultivation methods.[33][34] By the early to middle of the Holocene the process was complete.[34][33] From New Guinea, cultivated bananas spread westward into Island Southeast Asia through proximity (not migrations). They hybridized with other (possibly independently domesticated) subspecies of Musa acuminata as well as M. balbisiana in the Philippines, northern New Guinea, and possibly Halmahera. These hybridization events produced the triploid cultivars of bananas commonly grown today.[31]

Spread

From Island Southeast Asia, bananas became part of the staple domesticated crops of Austronesian peoples and were spread during their voyages and ancient maritime trading routes into Oceania, East Africa, South Asia, and Indochina.[31][32]

These ancient introductions resulted in the banana subgroup now known as the true plantains, which include the East African Highland bananas and the Pacific plantains (the Iholena and Maoli-Popo'ulu subgroups). East African Highland bananas originated from banana populations introduced to Madagascar probably from the region between Java, Borneo, and New Guinea; while Pacific plantains were introduced to the Pacific Islands from either eastern New Guinea or the Bismarck Archipelago.[31]

Phytolith discoveries in Cameroon dating to the first millennium BCE[35] triggered an as yet unresolved debate about the date of first cultivation in Africa. There is linguistic evidence that bananas were known in East Africa or Madagascar around that time.[36] The earliest prior evidence indicates that cultivation dates to no earlier than the late 6th century CE.[37] It is likely, however, that bananas were brought at least to Madagascar if not to the East African coast during the phase of Malagasy colonization of the island from South East Asia c. 400 CE.[38] Glucanase and two other proteins specific to bananas were found in dental calculus from the early Iron Age (12th century BCE) Philistines in Tel Erani in the southern Levant.[39]

Another wave of introductions later spread bananas to other parts of tropical Asia, particularly Indochina and the Indian subcontinent.[31] However, there is evidence that bananas were known to the Indus Valley civilisation from phytoliths recovered from the Kot Diji archaeological site in Pakistan. This may indicate very early dispersal of bananas by Austronesian traders by sea from as early as 2000 BCE, or they may have come from local wild Musa species used for fiber or as ornamentals, not food.[32] Southeast Asia remains the region of primary diversity of the banana. Areas of secondary diversity are found in Africa, indicating a long history of banana cultivation there.[40]

Arab Agricultural Revolution

The banana may have been present in isolated locations elsewhere in the Middle East on the eve of Islam. The spread of Islam was followed by far-reaching diffusion. There are numerous references to it in Islamic texts (such as poems and hadiths) beginning in the 9th century. By the 10th century the banana appears in texts from Palestine and Egypt. From there it diffused into North Africa and Muslim Iberia during the Arab Agricultural Revolution.[41][42] An article on banana tree cultivation is included in Ibn al-'Awwam's 12th-century agricultural work, Kitāb al-Filāḥa (Book on Agriculture).[43] During the Middle Ages, bananas from Granada were considered among the best in the Arab world.[42] Bananas were certainly grown in the Christian Kingdom of Cyprus by the late medieval period. Writing in 1458, the Italian traveller and writer Gabriele Capodilista wrote favourably of the extensive farm produce of the estates at Episkopi, near modern-day Limassol, including the region's banana plantations.[44]

Columbian exchange

Bananas were encountered by European explorers during the Magellan expedition in 1521, in both Guam and the Philippines. Lacking a name for the fruit, the ship's historian Antonio Pigafetta described them as "figs more than one palm long."[45][46]: 130, 132 Bananas were introduced to South America by Portuguese sailors who brought them from West Africa in the 16th century.[47] Southeast Asian banana cultivars, as well as abaca grown for fibers, were introduced to North and Central America by the Spanish from the Philippines, via the Manila galleons.[48] Many wild banana species and cultivars exist in India, China, and Southeast Asia.[49]

-

Original native ranges of the ancestors of modern edible bananas. Musa acuminata (green), Musa balbisiana (orange)[50]

-

Fruits of wild-type bananas have numerous large, hard seeds.

-

Actual and probable diffusion of bananas during the Arab Agricultural Revolution (700–1500 CE)[42]

-

Illustration of fruit and plant from Acta Eruditorum, 1734

Plantation cultivation

In the 15th and 16th centuries, Portuguese colonists started banana plantations in the Atlantic Islands, Brazil, and western Africa.[52] North Americans began consuming bananas on a small scale at very high prices shortly after the Civil War, though it was only in the 1880s that the food became more widespread.[53] As late as the Victorian Era, bananas were not widely known in Europe, although they were available.[52] The earliest modern plantations originated in Jamaica and the related Western Caribbean Zone, including most of Central America. It involved the combination of modern transportation networks of steamships and railroads with the development of refrigeration that allowed more time between harvesting and ripening. North American shippers like Lorenzo Dow Baker and Andrew Preston, the founders of the Boston Fruit Company started this process in the 1870s, but railroad builders like Minor C. Keith participated, culminating in the multi-national giant corporations like Chiquita and Dole.[53] These companies were monopolistic, vertically integrated (controlling growing, processing, shipping and marketing) and usually used political manipulation to build enclave economies (internally self-sufficient, virtually tax exempt, and export-oriented, contributing little to the host economy). Their political maneuvers, which gave rise to the term banana republic for states such as Honduras and Guatemala, included working with local elites and their rivalries to influence politics or playing the international interests of the United States, especially during the Cold War, to keep the political climate favorable to their interests.[54] In the modern United States, Hawaii is by far the largest banana producer, followed by Florida.[55]

Peasant cultivation

The vast majority of the world's bananas are cultivated for family consumption or for sale on local markets. India is the world leader in this sort of production, but many other Asian and African countries where climate and soil conditions allow cultivation also host large populations of banana growers who sell at least some of their crop.[56] Peasants with smallholdings of 1 to 2 acres in the Caribbean produce bananas for the world market, often alongside other crops.[57]

Modern cultivation

Bananas are propagated asexually from offshoots. The plant is allowed to produce two shoots at a time; a larger one for immediate fruiting and a smaller "sucker" or "follower" to produce fruit in 6–8 months.[8] As a non-seasonal crop, bananas are available fresh year-round.[58] They are grown in some 135 countries.[59]

Cavendish

In global commerce in 2009, by far the most important cultivars belonged to the triploid Musa acuminata AAA group of Cavendish group bananas.[60] It is unclear if any existing cultivar can replace Cavendish bananas, so various hybridisation and genetic engineering programs are attempting to create a disease-resistant, mass-market banana. One such strain that has emerged is the Taiwanese Cavendish or Formosana.[61]

Ripening

Export bananas are picked green, and ripened in special rooms upon arrival in the destination country. These rooms are air-tight and filled with ethylene gas to induce ripening. This mimics the normal production of this gas as a ripening hormone.[62][63] Ethylene stimulates the formation of amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch into sugar, influencing the taste. Ethylene signals the production of pectinase, an enzyme which breaks down the pectin between the cells of the banana, causing the banana to soften as it ripens.[62][63] The vivid yellow color consumers normally associate with supermarket bananas is caused by ripening around 18 °C (64 °F), and does not occur in Cavendish bananas ripened in tropical temperatures (over 27 °C (81 °F)).[64]

Storage and transport

Bananas are transported over long distances from the tropics to world markets.[65] To obtain maximum shelf life, harvest comes before the fruit is mature. The fruit requires careful handling, rapid transport to ports, cooling, and refrigerated shipping. The goal is to prevent the bananas from producing their natural ripening agent, ethylene. This technology allows storage and transport for 3–4 weeks at 13 °C (55 °F). On arrival, bananas are held at about 17 °C (63 °F) and treated with a low concentration of ethylene. After a few days, the fruit begins to ripen and is distributed for final sale. Ripe bananas can be held for a few days at home. If bananas are too green, they can be put in a brown paper bag with an apple or tomato overnight to speed up the ripening process.[66]

Sustainability

The excessive use of fertilizers contributes greatly to eutrophication in streams and lakes, and harms aquatic life after algal blooms deprive fish of oxygen. It has been theorized that destruction of 60% of coral reefs along the coasts of Costa Rica is partially from sediments from banana plantations. Another issue is the deforestation associated with expanding banana production. As monocultures rapidly deplete soil nutrients plantations expand to areas with rich soils and cut down forests, which also affects soil erosion and degradation, and increases frequency of flooding. The World Wildlife Fund stated that banana production produced more waste than any other agricultural sector, with discarded banana plants, bags used to cover the bananas, strings to tie them, and containers for transport.[67]

Voluntary sustainability standards such as Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade are being used to address some of these issues. Bananas production certified in this way grew rapidly at the start of the 21st century to represent 36% of banana exports by 2016.[68]

Breeding

Mutation breeding can be used in this crop. Aneuploidy is a source of significant variation in allotriploid varieties. For one example, it can be a source of TR4 resistance. Lab protocols have been devised to screen for such aberrations and for possible resulting disease resistances.[69] Wild Musa spp. provide useful resistance genetics, and are vital to breeding for TR4 resistance, as shown in introgressed resistance from wild relatives.[70]

The Honduran Foundation for Agricultural Research attempted to exploit the rare cases of seed production to create disease-resistant varieties by conventional breeding; 30,000 commercial banana plants were hand-pollinated with pollen from wild fertile Asian fruit, producing 400 tonnes, which contained about fifteen seeds, of which four or five germinated. Further breeding with wild bananas yielded a new seedless variety resistant to both black Sigatoka and Panama disease.[71]

Production and export

World

| Bananas | Plantains | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 34.5 | 34.5 | ||

| 11.8 | 11.8 | ||

| 10.4 | 10.4 | ||

| 9.2 | 9.2 | ||

| 5.9 | 3.1 | 9.0 | |

| 8.0 | 8.0 | ||

| 6.1 | 0.9 | 6.9 | |

| 6.9 | 6.9 | ||

| 0.8 | 4.9 | 5.7 | |

| 0.9 | 4.7 | 5.5 | |

| 2.5 | 2.5 | 5.0 | |

| 4.8 | 0.3 | 5.0 | |

| 0.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 | |

| 4.6 | 4.6 | ||

| 3.5 | 0.6 | 4.1 | |

| 2.2 | 0.9 | 3.1 | |

| 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.6 | |

| 0.5 | 2.1 | 2.6 | |

| 2.6 | 2.6 | ||

| 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.5 | |

| 2.5 | 2.5 | ||

| 2.4 | 2.4 | ||

| World | 135.1 | 44.2 | 179.3 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[72] Note: Some countries distinguish between bananas and plantains, but four of the top six producers do not, thus necessitating comparisons using the total for bananas and plantains combined. | |||

Bananas are exported in larger volume and to a larger value than any other fruit.[61] In 2022, world production of bananas and plantains combined was 179 million tonnes, led by India and China with a combined total of 26% of global production. Other major producers were Uganda, Indonesia, the Philippines, Nigeria and Ecuador.[72] As reported for 2013, total world exports were 20 million tonnes of bananas and 859,000 tonnes of plantains.[73] Ecuador and the Philippines were the leading exporters with 5.4 and 3.3 million tonnes, respectively, and the Dominican Republic was the leading exporter of plantains with 210,350 tonnes.[73]

Developing countries

Bananas and plantains are a major staple food crop for millions of people in developing countries. In many tropical countries, the main cultivars produce green (unripe) bananas used for cooking. Most producers are small-scale farmers either for home consumption or local markets. Because bananas and plantains produce fruit year-round, they provide a valuable food source during the hunger season between harvests of other crops. Bananas and plantains are thus important for global food security.[74]

Pests

Nematodes

Banana roots are subject to damage from multiple species of parasitic nematodes. Radopholus similis causes nematode root rot, the most serious nematode disease of bananas in economic terms.[75] Root-knot is the result of infection by species of Meloidogyne,[76] while root-lesion is caused by species of Pratylenchus,[77] and spiral nematode root damage is the result of infection by Helicotylenchus species.[78]

Insects

Among the main insect pests of banana cultivation are two beetles that cause substantial economic losses, the banana borer Cosmopolites sordidus and the banana stem weevil Odoiporus longicollis. Other significant pests include aphids and scarring beetles.[79]

Diseases

Although in no danger of outright extinction, bananas of the Cavendish group, which dominate the global market, are under threat. Its predecessor 'Gros Michel', discovered in the 1820s, was similarly dominant but had to be replaced after widespread infections of Panama Disease. Monocropping of Cavendish similarly leaves it susceptible to disease and so threatens both commercial cultivation and small-scale subsistence farming.[80][81] Within the data gathered from the genes of hundreds of bananas, the botanist Julie Sardos has found several wild banana ancestors currently unknown to scientists, whose genes could provide a means of defense against banana crop diseases.[82]

Some commentators have remarked that those variants which could replace what much of the world considers a "typical banana" are so different that most people would not consider them the same fruit, and blame the decline of the banana on monogenetic cultivation driven by short-term commercial motives.[54] Overall, fungal diseases are disproportionately important to small island developing states.[83]

Panama disease

Panama disease is caused by a Fusarium soil fungus, which enters the plants through the roots and travels with water into the trunk and leaves, producing gels and gums that cut off the flow of water and nutrients, causing the plant to wilt, and exposing the rest of the plant to lethal amounts of sunlight. Prior to 1960, almost all commercial banana production centered on the Gros Michel cultivar, which was highly susceptible.[84] Cavendish was chosen as the replacement for Gros Michel because, among resistant cultivars, it produces the highest quality fruit. However, more care is required for shipping the Cavendish,[85] and its quality compared to Gros Michel is debated.[86]

Fusarium wilt TR4

Fusarium wilt TR4, a reinvigorated strain of Panama disease, was discovered in 1993. This virulent form of Fusarium wilt has destroyed Cavendish plantations in several southeast Asian countries and spread to Australia and India.[87] As the soil-based fungi can easily be carried on boots, clothing, or tools, the wilt spread to the Americas despite years of preventive efforts.[87] Without genetic diversity, Cavendish is highly susceptible to TR4, and the disease endangers its commercial production worldwide.[88] The only known defense to TR4 is genetic resistance.[87] This is conferred either by RGA2, a gene isolated from a TR4-resistant diploid banana, or by the nematode-derived Ced9.[89][90] This may be achieved by genetic modification.[89][90] Experts state the need to enrich banana biodiversity by producing diverse new banana varieties, not just having a focus on the Cavendish.[87]

Black sigatoka

Black sigatoka is a fungal leaf spot disease first observed in Fiji in 1963 or 1964. It is caused by the ascomycete Mycosphaerella fijiensis. The disease, also called black leaf streak, has spread to banana plantations throughout the tropics from infected banana leaves used as packing material. It affects all main cultivars of bananas and plantains (including the Cavendish cultivars[91]), impeding photosynthesis by blackening parts of the leaves, eventually killing the entire leaf. Starved for energy, fruit production falls by 50% or more, and the bananas that do grow ripen prematurely, making them unsuitable for export. The fungus has shown ever-increasing resistance to treatment, with the current expense for treating 1 hectare (2.5 acres) exceeding US$1,000 per year; spraying with fungicides may be required as often as 50 times a year. In addition to the expense, there is the question of how long intensive spraying can be environmentally justified.[92][93]

Banana bunchy top virus

Banana bunchy top virus (BBTV) is a plant virus of the genus Babuvirus, family Nanonviridae affecting Musa spp. (including banana, abaca, plantain and ornamental bananas) and Ensete spp. in the family Musaceae.[94] Banana bunchy top disease (BBTD) symptoms include dark green streaks of variable length in leaf veins, midribs and petioles. Leaves become short and stunted as the disease progresses, becoming 'bunched' at the apex of the plant. Infected plants may produce no fruit or the fruit bunch may not emerge from the pseudostem.[95] The virus is transmitted by the banana aphid Pentalonia nigronervosa and is widespread in Southeast Asia, Asia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Oceania and parts of Africa. There is no cure for BBTD, but it can be effectively controlled by the eradication of diseased plants and the use of virus-free planting material.[96] No resistant cultivars have been found, but varietal differences in susceptibility have been reported. The commercially important Cavendish subgroup is severely affected.[95]

Banana bacterial wilt

Banana bacterial wilt (BBW) is a bacterial disease caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum.[97] First identified on a close relative of bananas, Ensete ventricosum, in Ethiopia in the 1960s,[98] BBW occurred in Uganda in 2001 affecting all banana cultivars. Since then BBW has been diagnosed in Central and East Africa including the banana growing regions of Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Burundi, and Uganda.[99]

Conservation of genetic diversity

Given the narrow range of genetic diversity present in bananas and the many threats via biotic (pests and diseases) and abiotic threats (such as drought) stress, conservation of the full spectrum of banana genetic resources is ongoing.[100] In 2024, the economist Pascal Liu of the FAO described the impact of global warming as an "enormous threat" to the world supply of bananas.[101]

Banana germplasm is conserved in many national and regional gene banks, and at the world's largest banana collection, the International Musa Germplasm Transit Centre, managed by Bioversity International and hosted at KU Leuven in Belgium.[102] Musa cultivars are usually seedless, and options for their long-term conservation are constrained by the vegetative nature of the plant's reproductive system. Consequently, they are conserved by three main methods: in vivo (planted in field collections), in vitro (as plantlets in test tubes within a controlled environment), and by cryopreservation (meristems conserved in liquid nitrogen at −196 °C).[100]

Genes from wild banana species are conserved as DNA and as cryopreserved pollen[100] and banana seeds from wild species are also conserved, although less commonly, as they are difficult to regenerate. In addition, bananas and their crop wild relatives are conserved in situ (in wild natural habitats where they evolved and continue to do so). Diversity is also conserved in farmers' fields where continuous cultivation, adaptation and improvement of cultivars is often carried out by small-scale farmers growing traditional local cultivars.[103]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 371 kJ (89 kcal) |

22.84 g | |

| Sugars | 12.23 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.6 g |

0.33 g | |

1.09 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3% 0.031 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 6% 0.073 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.665 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 7% 0.334 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 24% 0.4 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 5% 20 μg |

| Choline | 2% 9.8 mg |

| Vitamin C | 10% 8.7 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron | 1% 0.26 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 27 mg |

| Manganese | 12% 0.27 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 22 mg |

| Potassium | 12% 358 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.15 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 74.91 g |

Link to USDA Database entry

values are for edible portion | |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[104] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[105] | |

A raw banana (not including the peel) is 75% water, 23% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat. A reference amount of 100 grams (3.5 oz) supplies 89 calories, 31% of the Daily Value of vitamin B6, and moderate amounts of vitamin C, manganese, potassium, and dietary fiber, with no other micronutrients in significant content (table).

Although bananas are commonly thought to contain exceptional potassium content,[106][107] their actual potassium content is not high per typical food serving, having only 12% of the Daily Value for potassium (considered a moderate level of the DV; table). The potassium-content ranking for bananas among fruits, vegetables, legumes, and many other foods is relatively medium.[108][109]

Individuals with a latex allergy may experience a reaction to bananas.[110]

Uses

Culinary

Fruit

Bananas are a staple starch for many tropical populations. Depending upon cultivar and ripeness, the flesh can vary in taste from starchy to sweet, and texture from firm to mushy. Both the skin and inner part can be eaten raw or cooked. The primary component of the aroma of fresh bananas is isoamyl acetate (also known as banana oil), which, along with several other compounds such as butyl acetate and isobutyl acetate, is a significant contributor to banana flavor.[111]

Plantains are eaten cooked, such as made into fritters.[112] Pisang goreng, bananas fried with batter is a popular street food in Southeast Asia.[113] Bananas feature in Philippine cuisine, with desserts like maruya banana fritters.[114] Bananas can be made into fruit preserves.[115] Banana chips are a snack produced from sliced and fried bananas, such as in Kerala.[116] Dried bananas are ground to make banana flour.[117]

-

Banana curry with lemon, Andhra Pradesh, India

-

Pisang goreng fried banana in batter, a popular snack in Indonesia

-

Banana in sweet gravy, known as pengat pisang in Malaysia

Flowers

Banana flowers (also called "banana hearts" or "banana blossoms") are used as a vegetable[118] in South Asian and Southeast Asian cuisine. The flavor resembles that of artichoke. As with artichokes, both the fleshy part of the bracts and the heart are edible.[119]

-

Banana flowers and leaves on sale in Thailand

-

Kilawin na pusô ng saging, a Filipino dish of banana flowers

Leaf

Banana leaves are large, flexible, and waterproof. While generally too tough to actually be eaten, they are often used as ecologically friendly disposable food containers or as "plates" in South Asia and several Southeast Asian countries.[120] In Indonesian cuisine, banana leaf is employed in cooking methods like pepes and botok; banana leaf packages containing food ingredients and spices are cooked in steam or in boiled water, or are grilled on charcoal. Certain types of tamales are wrapped in banana leaves instead of corn husks.[121]

When used so for steaming or grilling, the banana leaves protect the food ingredients from burning and add a subtle sweet flavor.[1] In South India, it is customary to serve traditional food on a banana leaf.[122] In Tamil Nadu (India), dried banana leaves are used as to pack food and to make cups to hold liquid food items.[123]

-

Banana leaf as disposable plate for chicken satay in Java

-

Nicaraguan Nacatamales, in banana leaves, ready to be steamed

Trunk

The tender core of the banana plant's trunk is also used in South Asian and Southeast Asian cuisine. Examples include the Burmese dish mohinga, and the Filipino dishes inubaran and kadyos, manok, kag ubad.[124][125]

-

Kaeng yuak, a northern Thai curry of the core of the banana plant

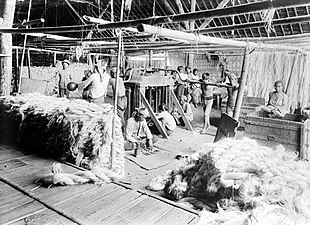

Paper and textiles

Banana fiber harvested from the pseudostems and leaves has been used for textiles in Asia since at least the 13th century. Both fruit-bearing and fibrous banana species have been used.[126] In the Japanese system Kijōka-bashōfu, leaves and shoots are cut from the plant periodically to ensure softness. Harvested shoots are first boiled in lye to prepare fibers for yarn-making. These banana shoots produce fibers of varying degrees of softness, yielding yarns and textiles with differing qualities for specific uses. For example, the outermost fibers of the shoots are the coarsest, and are suitable for tablecloths, while the softest innermost fibers are desirable for kimono and kamishimo. This traditional Japanese cloth-making process requires many steps, all performed by hand.[127] Banana paper can be made either from the bark of the banana plant, mainly for artistic purposes, or from the fibers of the stem and non-usable fruits. The paper may be hand-made or industrially processed.[128]

-

Packing Manila hemp (Musa textilis) into bales, Java

-

Weaving looms processing Manila hemp fabric

-

A modern Manila hemp bag by the fashion company QWSTION

Other uses

The large leaves of bananas may also be used as umbrellas.[1]

Banana peel may have capability to extract heavy metal contamination from river water, similar to other purification materials.[129][130] Waste bananas can be used to feed livestock.[131]

As with all living things, potassium-containing bananas emit radioactivity at low levels occurring naturally from the potassium-40 (K-40) isotope.[132] The banana equivalent dose of radiation was developed in 1995 as a simple teaching-tool to educate the public about the natural, small amount of K-40 radiation occurring in everyone and in common foods.[133][106]

Cultural roles

Arts

The Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō is named after the Japanese word 芭蕉 (Bashō) for the Japanese banana. The Bashō planted in his garden by a grateful student became a source of inspiration to his poetry, as well as a symbol of his life and home.[134]

The song "Yes! We Have No Bananas" was written by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn and originally released in 1923; for many decades, it was the best-selling sheet music in history. Since then the song has been rerecorded several times and has been particularly popular during banana shortages.[135][136]

A person slipping on a banana peel has been a staple of physical comedy for generations. An American comedy recording from 1910 features a popular character of the time, "Uncle Josh", claiming to describe his own such incident.[137]

The cover artwork for the debut album of The Velvet Underground features a banana made by Andy Warhol. On the original vinyl LP version, the design allowed the listener to "peel" this banana to find a pink, peeled phallic banana on the inside.[138]

Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan created a concept art piece titled Comedian[139] involving taping a banana to a wall using silver duct tape. The piece was exhibited briefly at the Art Basel in Miami before being removed from the exhibition and eaten without permission in another artistic stunt titled Hungry Artist by New York artist David Datuna.[140]

Religion and folklore

In India, bananas serve a prominent part in many festivals and occasions of Hindus. In South Indian weddings, particularly Tamil weddings, banana trees are tied in pairs to form an arch as a blessing to the couple for a long-lasting, useful life.[141][142]

In Thailand, it is believed that a certain type of banana plant may be inhabited by a spirit, Nang Tani, a type of ghost related to trees and similar plants that manifests itself as a young woman.[143] Often people tie a length of colored satin cloth around the pseudostem of the banana plants.[144]

In Malay folklore, the ghost known as Pontianak is associated with banana plants (pokok pisang), and its spirit is said to reside in them during the day.[145]

See also

- Banana (slur), the use of the word and actual fruit as an insult

- Corporación Bananera Nacional

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

- Orange, another fruit exported and consumed in large quantities

- United Brands Company v Commission of the European Communities

References

- ^ a b c d Morton, Julia F. (2013). "Banana". Fruits of warm climates. Echo Point Books & Media. pp. 29–46. ISBN 978-1-62654-976-0. OCLC 861735500. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009 – via www.hort.purdue.edu.

- ^ Picq, Claudine; INIBAP, eds. (2000). Bananas (PDF) (English ed.). Montpellier: International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantains/International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. ISBN 978-2-910810-37-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b c Stover & Simmonds 1987, pp. 5–17.

- ^ Stover & Simmonds 1987, p. 212.

- ^ Verrill, A. Hyatt (1939). Wonder Plants and Plant Wonders. New York: Appleton-Century Company. p. 49 (photo with caption).

- ^ Flindt, Rainer (2006). Amazing Numbers in Biology. Berlin: Springer Verlag. p. 149.

- ^ a b Ploetz et al. 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b Stover & Simmonds 1987, pp. 244–247.

- ^ Office of the Gene Technology Regulator 2008.

- ^ "Banana plant". Britannica. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Smith, James P. (1977). Vascular Plant Families. Eureka, California: Mad River Press. ISBN 978-0-916422-07-3.

- ^ Warkentin, Jon (2004). "How to make a Banana Split". University of Manitoba. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ Simmonds, N.W. (1962). "Where our bananas come from". New Scientist. 16 (307): 36–39. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ^ Christelová, Pavla; Valárik, Miroslav; Hřibová, Eva; De Langhe, Edmond; Doležel, Jaroslav (2011). "A multi gene sequence-based phylogeny of the Musaceae (banana) family". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (1): 103. Bibcode:2011BMCEE..11..103C. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-103. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3102628. PMID 21496296.

- ^ a b "Musa paradisiaca". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Li, Xiuxiu; Yu, Sheng; Cheng, Zhihao; Chang, Xiaojun; Yun, Yingzi; Jiang, Mengwei; et al. (2024). "Origin and evolution of the triploid cultivated banana genome". Nature Genetics. 56 (1): 136–142. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01589-3. hdl:1854/LU-01HHJ2ZMPK1880RM96GMJWM4SQ. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 38082204.

- ^ a b Search for "Musa", "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Hyam, R.; Pankhurst, R.J. (1995). Plants and their names : a concise dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-19-866189-4.

- ^ Schapper, Antoinette (2017). "Farming and the Trans-New Guinea family". In Robbeets, Martine; Savelyev, Alexander (eds.). Language dispersal beyond farming (PDF). John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 155–181. ISBN 978-90-272-1255-9. which (p. 169) cites Blench, Roger (2016). "Things your classics master never told you: a borrowing from Trans New Guinea languages into Latin". Academia.edu.

- ^ "Banana". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Bailey, Liberty Hyde (1916). The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. Macmillan. pp. 2076–2079. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Valmayor et al. 2000.

- ^ a b Constantine, D.R. "Musa paradisiaca". Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Porcher, Michel H. (July 19, 2002). "Sorting Musa names". The University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on March 2, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Valmayor et al. 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Ploetz et al. 2007, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Gibert, Olivier; Dufour, Dominique; Giraldo, Andrés; Sánchez, Teresa; Reynes, Max; Pain, Jean-Pierre; González, Alonso; Fernández, Alejandro; Díaz, Alberto (2009). "Differentiation between Cooking Bananas and Dessert Bananas. 1. Morphological and Compositional Characterization of Cultivated Colombian Musaceae (Musa sp.) in Relation to Consumer Preferences". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (17): 7857–7869. doi:10.1021/jf901788x. PMID 19691321.

- ^ Valmayor et al. 2000, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Englberger, Lois (2003). "Carotenoid-rich bananas in Micronesia" (PDF). InfoMusa. 12 (2): 2–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Nelson, Ploetz & Kepler 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Denham, Tim (October 2011). "Early Agriculture and Plant Domestication in New Guinea and Island Southeast Asia". Current Anthropology. 52 (S4): S379–S395. doi:10.1086/658682. hdl:1885/75070. S2CID 36818517.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Dorian Q.; Boivin, Nicole; Hoogervorst, Tom; Allaby, Robin (January 2, 2015). "Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals". Antiquity. 85 (328): 544–558. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067934.

- ^ a b Roberts, Patrick; Hunt, Chris; Arroyo-Kalin, Manuel; Evans, Damian; Boivin, Nicole (2017-08-03). "The deep human prehistory of global tropical forests and its relevance for modern conservation" (PDF). Nature Plants. 3 (8). Nature Portfolio: 17093. doi:10.1038/nplants.2017.93. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 28770823. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ a b Harris, David R.; Hillman, Gordon C., eds. (1989). Foraging and Farming — The Evolution of Plant Exploitation. London: Routledge. p. 766. doi:10.4324/9781315746425. ISBN 978-1315746425. S2CID 140588504.

- ^ Mbida, V.M.; Van Neer, W.; Doutrelepont, H.; Vrydaghs, L. (2000). "Evidence for banana cultivation and animal husbandry during the first millennium BCE in the forest of southern Cameroon" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (2): 151–162. Bibcode:2000JArSc..27..151M. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0447. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Zeller, Friedrich J. (2005). "Herkunft, Diversität und Züchtung der Banane und kultivierter Zitrusarten (Origin, diversity and breeding of banana and cultivated citrus)" (PDF). Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, Supplement 81 (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Lejju, B. Julius; Robertshaw, Peter; Taylor, David (2005). "Africa's earliest bananas?" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 33: 102–113. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.06.015. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2007.

- ^ Randrianja, Solofo; Ellis, Stephen (2009). Madagascar: A Short History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-947-1.

- ^ Scott, Ashley; et al. (Jan 12, 2021). "Exotic foods reveal contact between South Asia and the Near East during the second millennium BCE". PNAS. 118 (2): e2014956117. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11814956S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2014956117. PMC 7812755. PMID 33419922.

- ^ Ploetz et al. 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Watson, Andrew M. (1974). "The Arab Agricultural Revolution and Its Diffusion, 700–1100". The Journal of Economic History. 34 (1): 8–35. doi:10.1017/S0022050700079602. JSTOR 2116954. S2CID 154359726.

- ^ a b c Watson, Andrew (1983). "Part 1. The chronology of diffusion: 8. Banana, plantain". Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24711-5.

- ^ Ibn al-'Awwam, Yahya (1864). Le livre de l'agriculture d'Ibn-al-Awam (kitab-al-felahah) (in French). Translated by J.-J. Clement-Mullet. Paris: A. Francke Verlag. pp. 368–370 (ch. 7 - Article 48). OCLC 780050566. (pp. 368-370 (Article XLVIII)

- ^ Jennings, Ronald (1992). Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640. New York: NYU Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8147-4181-8.

- ^ Amano, Noel; Bankoff, Greg; Findley, David Max; Barretto-Tesoro, Grace; Roberts, Patrick (February 2021). "Archaeological and historical insights into the ecological impacts of pre-colonial and colonial introductions into the Philippine Archipelago". The Holocene. 31 (2): 313–330. Bibcode:2021Holoc..31..313A. doi:10.1177/0959683620941152. hdl:21.11116/0000-0006-CB04-1. S2CID 225586504.

- ^ Nowell, C. E. (1962). "Antonio Pigafetta's account". Magellan's Voyage Around the World. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015008001532. OCLC 347382.

- ^ Gibson, Arthur C. "Bananas and plantains". UCLA. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Guzmán-Rivas, Pablo (1960). "Geographic Influences of the Galleon Trade on New Spain". Revista Geográfica. 27 (53): 5–81. ISSN 0031-0581. JSTOR 41888470.

- ^ Peed, Mike (January 10, 2011). "We Have No Bananas: Can Scientists Defeat a Devastating Blight?". The New Yorker. pp. 28–34. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ de Langhe, Edmond; de Maret, Pierre (2004). "Tracking the banana: its significance in early agriculture". In Hather, Jon G. (ed.). The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change. Routledge. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-203-20338-5. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Geoff (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ a b "Phora Ltd. – History of Banana". Phora-sotoby.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Koeppel, Dan (2008). Banana: The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World. New York: Hudson Street Press. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-0-452-29008-2.

- ^ a b "Big-business greed killing the banana – Independent". The New Zealand Herald. May 24, 2008. p. A19.

- ^ "Banana Market". University of Florida, IFAS Extension. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Office of the Gene Technology Regulator 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Clegg, Peter "The Development of the Windward Islands Banana Export Trade: Commercial Opportunity and Colonial Necessity," Society for Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers 1 (2000).

- ^ "How bananas are grown". Banana Link. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ "Where bananas are grown". ProMusa. 2013. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ "Apples and oranges are the top U.S. fruit choices". USDA Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ a b Gittleson, Kim (February 1, 2018). "Battling to save the world's bananas". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Fruit Ripening". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Ethylene Process". Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Ding, Phebe; Ahmad, S.H.; Razak, A.R.A.; Shaari, N.; Mohamed, M.T.M. (2007). "Plastid ultrastructure, chlorophyll contents, and colour expression during ripening of Cavendish banana (Musa acuminata 'Williams') at 17°C and 27°C" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 35 (2): 201–210. Bibcode:2007NZJCH..35..201D. doi:10.1080/01140670709510186. S2CID 83844509. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Arias, Pedro (2003). The World Banana Economy, 1985-2002. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 978-9251050576.

- ^ "How to Ripen Bananas". Chiquita. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ Cohen, Rebecca (2009-06-12). "Global issues for breakfast: The banana industry and its problems FAQ (Cohen mix)". SCQ. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- ^ Voora, V.; Larrea, C.; Bermudez, S. (2020). Global Market Report: Bananas. State of Sustainability Initiatives (Report).

- ^ Jankowicz-Cieslak, Joanna; Ingelbrecht, Ivan (2022). Jankowicz-Cieslak, Joanna; Ingelbrecht, Ivan L. (eds.). Efficient Screening Techniques to Identify Mutants with TR4 Resistance in Banana : Protocols. Berlin: Plant Breeding and Genetics Laboratory, Joint FAO/IAEA Centre of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, International Atomic Energy Agency, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 142. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-64915-2. ISBN 978-3-662-64914-5. OCLC 1323245754. S2CID 249207968.

- ^ Ismaila, Abubakar Abubakar; Ahmad, Khairulmazmi; Siddique, Yasmeen; et al. (2023). "Fusarium wilt of banana: Current update and sustainable disease control using classical and essential oils approaches". Horticultural Plant Journal. 9 (1). Elsevier: 1–28. Bibcode:2023HorPJ...9....1I. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2022.02.004. S2CID 247265619. Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences via KeAi Communications Co. Ltd. – Chinese Society for Horticultural Science and Institute of Vegetables and Flowers.

- ^ Pearce, Fred (18 January 2003). "Going bananas" (PDF). New Scientist. 177 (2378): 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-17.

- ^ a b "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Banana and plantain exports in 2013, Crops and livestock products/Regions/World list/Export quantity (pick lists)". Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2017. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ d'Hont, A.; Denoeud, F.; Aury, J. M.; Baurens, F. C.; Carreel, F.; Garsmeur, O.; et al. (2012). "The banana (Musa acuminata) genome and the evolution of monocotyledonous plants". Nature. 488 (7410): 213–217. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..213D. doi:10.1038/nature11241. PMID 22801500.

- ^ Sekora, N. S. and W. T. Crow. Burrowing nematode, Radopholus similis. EENY-542. University of Florida IFAS. 2012.

- ^ Jonathan, E. I.; Rajendran, G. (2000). "Pathogenic effect of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita on banana, Musa sp". Indian Journal of Nematology. 30 (1): 13–15.

- ^ Nyang’au, Douglas; Atandi, Janet; Cortada, Laura; Nchore, Shem; Mwangi, Maina; Coyne, Danny (2021-08-30). "Diversity of nematodes on banana (Musa spp.) in Kenya linked to altitude and with a focus on the pathogenicity of Pratylenchus goodeyi". Nematology. 24 (2): 137–147. doi:10.1163/15685411-bja10119. hdl:1854/LU-8735041. ISSN 1388-5545.

- ^ Zuckerman, B.M.; Strich-Hariri, D. (1963). "The life stages of Helicotylenchus multicinctus (Cobb) in banana roots". Nematology. 9 (3). E.J. Brill: 347–353. doi:10.1163/187529263x00872.

- ^ a b Padmanaban, B. (2018). "Pests of Banana". Pests and Their Management. Singapore: Springer Singapore. pp. 441–455. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8687-8_13. ISBN 978-981-10-8686-1.

- ^ "A future with no bananas?". New Scientist. May 13, 2006. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ^ Montpellier, Emile Frison (February 8, 2003). "Rescuing the banana". New Scientist. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2006.

- ^ Whang, Oliver (2022-10-17). "The Search Is on for Mysterious Banana Ancestors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ Thomas, Adelle; Baptiste, April; Martyr-Koller, Rosanne; Pringle, Patrick; Rhiney, Kevon (2020-10-17). "Climate Change and Small Island Developing States". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1). Annual Reviews: 1–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083355. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ Barker, C.L. (November 2008). "Conservation: Peeling Away". National Geographic Magazine.

- ^ Frost, Natasha (February 28, 2018). "A Quest for the Gros Michel, the Great Banana of Yesteryear". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Lessard, William (1992). The Complete Book of Bananas. W.O. Lessard. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0963316103.

- ^ a b c d Karp, Myles (August 12, 2019). "The banana is one step closer to disappearing". National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ "Risk assessment of Eastern African Highland Bananas and Plantains against TR4" (PDF). International Banana Symposium. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Dale, James; James, Anthony; Paul, Jean-Yves; et al. (November 14, 2017). "Transgenic Cavendish bananas with resistance to Fusarium wilt tropical race 4". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1496. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1496D. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01670-6. PMC 5684404. PMID 29133817.

- ^ a b "Researchers Develop Cavendish Bananas Resistant to Panama Disease". ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications) Crop Biotech Update. 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ Holmes, Bob (April 20, 2013). "Go Bananas". New Scientist. 218 (2913): 9–41. (Also at Holmes, Bob (April 20, 2013). "Nana from heaven? How our favourite fruit came to be". New Scientist. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.)

- ^ Marín, D. H.; Romero, R. A.; Guzmán, M.; Sutton, T. B. (2003). "Black sigatoka: An increasing threat to banana cultivation". Plant Disease. 87 (3). American Phytopathological Society (APS): 208–222. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.3.208. PMID 30812750.

- ^ "Mycosphaerella fijiensis v2.0". Joint Genome Institute, U.S. Department of Energy. 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ National Biological Information Infrastructure & IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group. Banana Bunchy Top Virus Archived April 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Global Invasive Species Database. N.p., July 6, 2005.

- ^ a b Thomas, JE (ed). 2015. MusaNet Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Musa Germplasm Archived September 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. 3rd edition. MusaLit, Bioversity International, Rome

- ^ Thomas, J.E.; Iskra-Caruana, M-L.; Jones, D.R. (1994). "Musa Disease Fact Sheet N° 4. Banana Bunchy Top Disease" (PDF). INIBAP. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Tushemereirwe, W.; Kangire, A.; Ssekiwoko, F.; Offord, L.C.; Crozier, J.; Boa, E.; Rutherford, M.; Smith, J.J. (2004). "First report of Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum on banana in Uganda". Plant Pathology. 53 (6): 802. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2004.01090.x.

- ^ Bradbury, J.F.; Yiguro, D. (1968). "Bacterial wilt of Enset (Ensete ventricosa) incited by Xanthomonas musacearum". Phytopathology. 58: 111–112.

- ^ Mwangi, M.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Ragama, P.; Tushemereirwe, R.K. (2007). "Assessment of banana planting practices and cultivar tolerance in relation to management of soilborne Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum". Crop Protection. 26 (8): 1203–1208. Bibcode:2007CrPro..26.1203M. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2006.10.017.

- ^ a b c "Banana". Genebank Platform. 2018. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (12 March 2024). "Banana prices to go up as temperatures rise, says expert". BBC News. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "International Musa Germplasm Transit Centre". Bioversity International. 2018. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "Global Strategy for the Conservation and Use of Musa Genetic Resources (B. Laliberté, compiler)". Montpellier, France: Bioversity International. 2016.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ a b Edwards, Gordon (2019). "About radioactive bananas" (PDF). Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Kraft, S. (August 4, 2011). "Bananas! Eating Healthy Will Cost You; Potassium Alone $380 Per Year". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ "Ranking of potassium content per 100 grams in common foods ("Foundation" only for search filter)". FoodData Central, United States Department of Agriculture. 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ "What you need to know about potassium". EatRight Ontario, Dietitians of Canada. 2019. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, J.S.; Erkek, E. (2004). "Latex allergy: diagnosis and management". Dermatologic Therapy. 17 (4): 289–301. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04024.x. PMID 15327474. S2CID 24748498.

- ^ Mui, Winnie W. Y.; Durance, Timothy D.; Scaman, Christine H. (2002). "Flavor and Texture of Banana Chips Dried by Combinations of Hot Air, Vacuum, and Microwave Processing". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 50 (7): 1883–1889. doi:10.1021/jf011218n. PMID 11902928. "Isoamyl acetate (9.6%) imparts the characteristic aroma typical of fresh bananas (13, 17−20), while butyl acetate (8.1%) and isobutyl acetate (1.4%) are considered to be character impact compounds of banana flavor."

- ^ Williams, Patrick. "Roast bream with fried plantain fritters and coconut sauce". BBC. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Kraig, Bruce; Sen, Colleen Taylor (2013). Street Food around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-59884-955-4.

- ^ Tsao, Kimberley (15 February 2023). "Turon, maruya, bitso-bitso and banana cue make it to Taste Atlas's list of 100 most popular deep-fried desserts in the world". GMA News. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Aimi Azira, S.; Wan Zunairah, W.I.; Nor Afizah, M.; M.A.R., Nor-Khaizura; S., Radhiah; M.R., Ismail Fitry; Z.A., Nur Hanani (2021-09-10). "Prevention of browning reaction in banana jam during storage by physical and chemical treatments". Food Research. 5 (5): 55–62. doi:10.26656/fr.2017.5(5).046.

- ^ Pereira, Ignatius (April 13, 2013). "The taste of Kerala". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Coghlan, Lea (May 13, 2014). "Business goes bananas". Queensland Country Life.

- ^ Solomon, C (1998). Encyclopedia of Asian Food (Periplus ed.). Australia: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85561-688-5. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ Watson, Molly (21 June 2022). "Banana Flowers". The Spruce Eats. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. See also the link on that page for Banana Flower Salad.

- ^ Nace, Trevor (March 25, 2019). "Thailand Supermarket Ditches Plastic Packaging For Banana Leaves". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Banana leaves transform texture of chicken tamales". The San Diego Union-Tribune. December 7, 2022.

- ^ Grover, Neha (27 December 2022). "Why South Indians Eat On Banana Leaves - Health Benefits And More". NDTV. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Kora, Aruna Jyothi (2019). "Leaves as dining plates, food wraps and food packing material: Importance of renewable resources in Indian culture". Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 43 (1). doi:10.1186/s42269-019-0231-6. ISSN 2522-8307.

- ^ Polistico, Edgie (2017). "Inubaran". Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary. Anvil Publishing. ISBN 9786214200870.

- ^ Polistico, Edgie (2017). "Kadyos, Manok, Kag Ubad". Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary. Anvil Publishing. ISBN 9786214200870.

- ^ Hendrickx, Katrien (2007). The Origins of Banana-fibre Cloth in the Ryukyus, Japan. Leuven University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-9058676146. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Traditional Crafts of Japan – Kijoka Banana Fiber Cloth". Association for the Promotion of Traditional Craft Industries. Archived from the original on November 4, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ Gupta, K. M. (November 13, 2014). Engineering Materials: Research, Applications and Advances. CRC Press. ISBN 9781482257984. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018.

- ^ Minard, Anne (March 11, 2011). "Is That a Banana in Your Water?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 26, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Castro, Renata S. D.; Caetano, LaéRcio; Ferreira, Guilherme; Padilha, Pedro M.; Saeki, Margarida J.; Zara, Luiz F.; Martines, Marco Antonio U.; Castro, Gustavo R. (2011). "Banana Peel Applied to the Solid Phase Extraction of Copper and Lead from River Water: Preconcentration of Metal Ions with a Fruit Waste". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 50 (6): 3446–3451. doi:10.1021/ie101499e. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Archimède, H.; Renaudeau, D.; Lessire, M. (2016). "Banana fruits". Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2018. Last updated on March 25, 2016, 10:36

- ^ Frame, Paul (January 20, 2009). "General information about K-40". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Mansfield, Gary (March 7, 1995). "Banana equivalent dose". Internal Dosimetry, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, University of California. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Shirane, Haruo (1998). Traces of Dreams: Landscape, Cultural Memory, and the Poetry of Bashō. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8047-3099-0.

- ^ Shaw, Arnold (1987). ""Yes! We have No Bananas"/"Charleston" (1923)". The Jazz Age: Popular Music in 1920s. Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780195060829. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017.

- ^ Dan Koeppel (2005). "Can This Fruit Be Saved?". Popular Science. 267 (2): 60–70. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017.

- ^ Stewart, Cal. "Collected Works of Cal Stewart part 2". Uncle Josh in a Department Store (1910). The Internet Archive. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ Bill DeMain (December 11, 2011). "The Stories Behind 11 Classic Album Covers". mental_floss. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ O'Neil, Luke (2019-12-06). "One banana, what could it cost? $120,000 – if it's art". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (2019-12-08). "Banana Splits: Spoiled by Its Own Success, the $120,000 Fruit Is Gone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ "Banana trees in weddings". Indian Mirror. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "Legends, myths and folklore of the banana tree in India - its use in traditional culture". EarthstOriez. May 2, 2017. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "Banana Tree Prai Lady Ghost". Thailand-amulets.net. March 19, 2012. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Spirits". Thaiworldview.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ "Pontianak- South East Asian Vampire". Castleofspirits.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

Bibliography

- Nelson, S.C.; Ploetz, R.C.; Kepler, A.K. (2006). "Musa species (bananas and plantains)" (PDF). In Elevitch, C.R (ed.). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Hōlualoa, Hawai'i: Permanent Agriculture Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (2008). The Biology of Musa L. (banana) (PDF). Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- Ploetz, R.C.; Kepler, A.K.; Daniells, J.; Nelson, S.C. (2007). "Banana and Plantain: An Overview with Emphasis on Pacific Island Cultivars" (PDF). In Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Hōlualoa, Hawai'i: Permanent Agriculture Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- Stover, R.H.; Simmonds, N.W. (1987). Bananas (3rd ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-46357-8.

- Valmayor, Ramón V.; Jamaluddin, S.H.; Silayoi, B.; Kusumo, S.; Danh, L.D.; Pascua, O.C.; Espino, R.R.C. (2000). Banana cultivar names and synonyms in Southeast Asia (PDF). Los Baños, Philippines: International Network for Improvement of Banana and Plantain – Asia and the Pacific Office. ISBN 978-971-91751-2-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

External links

- Bananas

- Berries

- Fruits originating in Asia

- Fiber plants

- Staple foods

- Tropical agriculture

- Tropical fruit

- Edible fruits

- Austronesian agriculture

- 1936 establishments in the United States

- Birds on coins

- Currencies introduced in 1936

- Early United States commemorative coins

- Fifty-cent coins

- History of Bridgeport, Connecticut

- United States silver coins

![Original native ranges of the ancestors of modern edible bananas. Musa acuminata (green), Musa balbisiana (orange)[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Banana_ancestors_%28Musa_acuminata_and_Musa_balbisiana%29_original_range.png/250px-Banana_ancestors_%28Musa_acuminata_and_Musa_balbisiana%29_original_range.png)

![Chronological dispersal of Austronesian peoples across the Indo-Pacific[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/Chronological_dispersal_of_Austronesian_people_across_the_Pacific_%28per_Benton_et_al%2C_2012%2C_adapted_from_Bellwood%2C_2011%29.png/250px-Chronological_dispersal_of_Austronesian_people_across_the_Pacific_%28per_Benton_et_al%2C_2012%2C_adapted_from_Bellwood%2C_2011%29.png)