Venlafaxine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 45% |

| Protein binding | 27% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 5 ± 2 hours (parent compound); 11 ± 2 hours (active metabolite) |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.122.418 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H27NO2 |

| Molar mass | 277.402 g/mol |

Venlafaxine hydrochloride is a prescription antidepressant first introduced by Wyeth in 1993. It belongs to class of antidepressants called serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI). As of August 2006, generic venlafaxine is available in the United States, and as of December 2006, generic venlafaxine is available in Canada. It was previously available only under the brand names Effexor and Effexor XR. It is also available in the UK under both names.

Trade names

Venlafaxine is marketed under the tradenames, Effexor®, Efectin®, Effexor XR®, Efectin ER® and Vandral Retard®

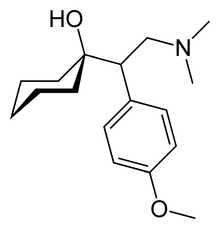

Description of compound

The chemical structure of venlafaxine is designated (R/S)-1-[2-(dimethylamino)-1-(4 methoxyphenyl)ethyl] cyclohexanol hydrochloride or (±)-1-[a [a- (dimethylamino)methyl] p-methoxybenzyl] cyclohexanol hydrochloride and it has the empirical formula of C17H27NO2. It is a white to off-white crystalline solid. Venlafaxine is structurally and pharmacologically related to the analgesic tramadol, but not to any of the conventional antidepressant drugs, including tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, MAOIs, or reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (RIMAs).[2]

Mechanism of action

Venlafaxine is a bicyclic antidepressant, and is usually categorized as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), but it has been referred to as a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor.[3][4] It works by blocking the transporter "reuptake" proteins for key neurotransmitters affecting mood, thereby leaving more active neurotransmitter in the synapse. The neurotransmitters affected are serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) Additionally, in high doses it weakly inhibits the reuptake of dopamine.[5]

Pharmacokinetics

Venlafaxine is well absorbed with at least 92% of an oral dose being absorbed into systemic circulation. Venlafaxine is extensively metabolized in the liver via the CYP2D6 isoenzyme to O-desmethylvenlafaxine, which is just as potent a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor as the parent compound, meaning that the differences in metabolism between extensive and poor metabolizers are not clinically important. Steady-state concentrations of venlafaxine and its metabolite are attained in the blood within 3 days. Therapeutic effects are usually achieved within 3 to 4 weeks. No accumulation of venlafaxine has been observed during chronic administration in healthy subjects. The primary route of excretion of venlafaxine and its metabolites is via the kidneys.[6] The half-life of venlafaxine is relatively short, therefore patients are directed to adhere to a strict medication routine, avoiding missing a dose. Even a single missed dose can result in the withdrawal symptoms.[7]

Indications

Approved

Venlafaxine is used primarily for the treatment of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder in adults only. It is also used for other general depressive disorders.[6]

Off-label / investigational uses

Many doctors are starting to prescribe venlafaxine "off label" for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy (in a similar manner to duloxetine) and migraine prophylaxis (in some people, however, venlafaxine can exacerbate or cause migraines). Studies have shown venlafaxine's effectiveness for these conditions.[8][9] It has also been found to reduce the severity of 'hot-flashes' in menopausal women.[10][11]

Substantial weight loss in patients with major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia has been noted, but the manufacturer does not recommend use as an anorectic either alone or in combination with phentermine or other amphetamine-like drugs.[6]

Venlafaxine is not approved for the treatment of depressive phases of bipolar disorder; this has some potential danger as venlafaxine can induce mania, mixed states, rapid cycling and/or psychosis in some bipolar patients, particularly if they are not also being treated with a mood stabilizer.[6] Venlafaxine is perhaps one of the most likely of all modern antidepressants to trigger manic and hypomanic states.

Contraindications

Venlafaxine is not recommended in patients hypersensitive to venlafaxine. It should never be used in conjunction with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), due to the potential to develop a potentially deadly condition known as serotonin syndrome. Caution should also be used in those with a seizure disorder. Venlafaxine is not approved for use in children or adolescents.[6] However, Wyeth does provide information on precautions if venlafaxine is prescribed to this age group for the treatment of non-approved conditions. Studies in these age groups have not established its efficacy or safety.[12]

Pregnancy, labor and delivery

There are no adequate and well controlled studies with venlafaxine in pregnant women. Therefore, venlafaxine should only be used during pregnancy if clearly needed.[6] Prospective studies have not shown any statistically significant congenital malformations.[13] There have, however, been some reports of effects on new born infants.[14] In view of the possibility of severe discontinuation syndrome and the difficulties this presents, use of venlafaxine for pregnant women is not generally indicated.[citation needed]

Dose range

Prescribed dosages are typically in the range of 75 to 225 mg per day, but higher dosages are sometimes used for the treatment of severe or treatment-resistant depression. Venlafaxine is sometimes prescribed in 37.5 mg per day dosages in patients with anxiety. Low doses only work on the serotonin reuptake mechanism (presumed defective in those with anxiety) therefore avoiding the anxiety inducing effects of norepinephrine reuptake experienced at higher doses. Because of its relatively short half-life of 5 hours, venlafaxine should be administered in divided dosages throughout the day. The extended release version (largely manufactured on spheronization equipment) eliminates this problem and has largely replaced the original in use.

Available forms

Effexor is distributed in pentagon-shaped peach-colored tablets of 25 mg, 37.5 mg, 50 mg, 75 mg, and 100 mg. There is also an extended-release version distributed in capsules of 37.5 mg (gray/peach), 75 mg (peach), and 150 mg (brownish red).

Venlafaxine Extended Release (XR)

Venlafaxine extended release is chemically the same as normal venlafaxine. The extended release version (sometimes referred to as controlled release) controls the release of the drug into the gastrointestinal tract over a longer period of time than normal venlafaxine. This results in a lower peak plasma concentration. Studies have shown that the extended release formula has a lower incidence of patients suffering from nausea as a side effect resulting in a lower number of patients stopping their treatment due to nausea.[15]

Effectiveness

Venlafaxine is an effective anti-depressant for many persons; however, it seems to be especially effective for those with treatment-resistant depression. Some of these persons have taken two or more antidepressants prior to venlafaxine with no relief. Patients suffering with severe long-term depression typically respond better to venlafaxine than other drugs. However, venlafaxine has been reported to be more difficult to discontinue than other anti-depressants. In addition, a September 2004 Consumer Reports study ranked venlafaxine as the most effective among six commonly prescribed antidepressants. Like most psychiatric medications, however, the results of such studies alone should not be relied upon by potential patients, as responses to psychiatric medications can vary significantly from individual to individual.

Adverse effects

As with most antidepressants, lack of sexual desire is a common side effect. Venlafaxine can raise blood pressure at high doses, so it is usually not the drug of choice for persons with hypertension.

It has a higher rate of treatment emergent mania than many modern antidepressants, and many people find it to be a more activating medication than other antidepressants. Paradoxically, some users find it highly sedating and find that it must be taken in the evening.

Suicide Ideation/Risk

A Black Box Warning has been issued with Effexor and with other SSRI and SNRI anti-depressants advising of risk of suicide. Thoughts of suicide (suicide ideation) as potential risk of suicide as shown in studies by Wyeth and reported on their datasheet for Effexor were twice that of placebo (4% compared to 2%, however, no suicides occurred in these trials).[6] The black box warnings advise physicians to carefully monitor patients for suicide risk at start of usage and whenever the dosage is changed. There is an additional risk if a physician misinterprets patient expression of adverse effects such as panic or akathisia as symptoms of worsening depression rather than effects of the medication and increases dose. Assessment of patient history and comorbid risk factors such as drug abuse are recommended when evaluating the safety of venlafaxine for individual patients. These cautions are emphasized in Wyeth's information sheet with special precautions if prescribed to children. The extent of this effect and the actual risk are not known as studies may exclude individuals with higher risk.

In the UK, one study evaluated whether risk factors for suicide were more prevalent among patients prescribed venlafaxine than patients prescribed other antidepressants. Results showed patients prescribed venlafaxine were more likely to have attempted suicide in the previous year, although it was concluded that venlafaxine had been selectively prescribed to a patient population with a higher burden of suicide risk factors to begin with, and that this might have led to a higher future risk of suicide independent of any drug effect. Studies with baseline data are required to determine the actual risk with venlafaxine.[16]

Several patients have reported acute relapse into depression upon withdrawal, along with a strong sensation of "electric shocks in the brain".[17]

Serotonin Syndrome

Another risk is Serotonin syndrome. This is a rare, however serious side effect that can be caused by interactions with other Central Nervous System depressant drugs and is potentially fatal.[18] This risk necessitates clear information to patients and proper medical history. For example, the drug abuse by at risk patients of certain non-prescription drugs can cause this serious effect and emphasizes the importance of good medical history sharing between General Practitioners and Psychiatrists as both may prescribe Venlafaxine. Involvement of family in awareness of risk factors is highlighted in Wyeth information sheets on Effexor.

Common side effects

- Nausea

- Ongoing Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Insomnia

- Vertigo

- Dry mouth

- Sexual dysfunction

- Sweating

- Vivid dreams

- Increased blood pressure

- Electric shock-like sensations also called "Brain shivers"

- Increased anxiety at the start of treatment

- Akathisia (Agitation)

Less common to rare side-effects

- Cardiac arrhythmia

- Increased serum cholesterol

- Gas or stomach pain

- Abnormal vision

- Nervousness, agitation or increased anxiety akathisia

- Panic Attacks

- Depressed feelings

- Suicidal thoughts suicidal ideation

- Confusion

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Loss of appetite

- Constipation

- Tremor

- Drowsiness

- Allergic skin reactions

- External bleeding

- Serious bone marrow damage (thrombocytopenia, agranulocytosis)

- Hepatitis

- Pancreatitis

- Seizure

- Tardive dyskinesia

- Difficulty swallowing

- Psychosis

- Hair Loss

- Hostility

- Activation of mania/hypomania.

- Weight Loss (of concern when treating anorexic patients)

- Weight gain (effect not clear, but of concern when treating young women who may have Body Dysmorphic Disorder).

- Homicidal Thoughts Homicidal Ideations

- Aggression

- Depersonalization

- Psychosis

Dose dependency of adverse events

A comparison of adverse event rates in a fixed-dose study comparing venlafaxine 75, 225, and 375 mg/day with placebo revealed a dose dependency for some of the more common adverse events associated with venlafaxine use. The rule for including events was to enumerate those that occurred at an incidence of 5% or more for at least one of the venlafaxine groups and for which the incidence was at least twice the placebo incidence for at least one venlafaxine group. Tests for potential dose relationships for these events (Cochran-Armitage Test, with a criterion of exact 2-sided p-value <= 0.05) suggested a dose-dependency for several adverse events in this list, including chills, hypertension, anorexia, nausea, agitation, dizziness, somnolence, tremor, yawning, sweating, and abnormal ejaculation.[6]

Physical and Psychological Dependency

In vitro studies revealed that venlafaxine has virtually no affinity for opiate, benzodiazepine, phencyclidine (PCP), or N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors. It has no significant CNS stimulant activity in rodents. In primate drug discrimination studies, venlafaxine showed no significant stimulant or depressant abuse liability.[6]

Notwithstanding these in-vitro and non-human research findings, some patients using venlafaxine may become dependent on this drug. This is especially noted if a patient misses a dose, but can also occur when reduction of dosage is done with a doctor's care. This may result in experiencing withdrawal symptoms described as severe discontinuation syndrome. The high risk of withdrawal symptoms may reflect venlafaxines short half-life.[19] Missing even a single dose can induce discontinuation effects in some patients.[7] Discontinuation is similar in nature to those of SSRIs such as Paroxetine (Paxil® or Seroxat®). Sudden discontinuation of venlafaxine has a high risk of causing potentially severe withdrawal symptoms.[20]

As the drug has direct impact on mood (i.e. anti-depressant), many users who have suffered the effects of attempted withdrawal from this drug define their dependency on the drug also as being addicted.[19] Although many other drugs can cause withdrawal symptoms which are not associated with addiction or dependence, for example, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, nitrates, diuretics, centrally acting antihypertensives, sympathomimetics, heparin, tamoxifen, dopaminergic agents, antipsychotics, and lithium,[19] addiction or dependence is a more common effect described for drugs that (are thought to, or may) improve mental well-being.[21] An internet petition of effexor users and family members with more than 12,000 signatories describes the impact of discontinuation of this drug. It is therefore important that prescribing doctors explain the details of this drug to patients with care.

- Brain shivers, also known as "the electric brain thing", "battery head", "brain zaps", "Blips", or "brain spasms", are a rare but notorious withdrawal symptom of certain antidepressants and have been seen with discontinuation of most SSRI antidepressants but specifically in sertraline, veneflaxine, paroxetine and duloxetine. Paresthesia and "electric shock sensations" are clinical terms used to describe this symptom. The brain shiver effect appears to be almost unique to those antidepressant chemicals that have an extremely short half-life in the body; that is, they are quick to disappear completely. This attribute of abruptness leaves the brain a relatively short time to adapt to a major neurochemical change when you stop taking the medication, and the symptoms may be caused by the brain's readjustment. There is no evidence that the shivers present any danger to the patient experiencing them.

Overdose

Most patients overdosing with venlafaxine develop only mild symptoms. However, severe toxicity is reported with the most common symptoms being CNS depression, serotonin toxicity, seizure, or cardiac conduction abnormalities.[22] Venlafaxines toxicity appears to be higher than other SSRIs, with a fatal toxic dose closer to that of the tricyclic antidepressants than the SSRIs. Doses of 900 mg or more are likely to cause moderate toxicity.[2] Deaths have been reported following large doses.[23][24]

On May 31st 2006, The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHPRA) UK has concluded its review into all the latest safety evidence relating to venlafaxine particularly looked at the risks associated with overdose. The advice are, the need for specialist supervision in those severely depressed or hospitalised patients who need doses 300mg or more; cardiac contra-indications are more targeted towards high risk groups; patients with uncontrolled hypertension should not take venlafaxine, and blood pressure monitoring is recommended for all patients; and updated advice on possible drug interactions. [25]

On October 25, 2006 Wyeth and the FDA notified healthcare professionals of revisions to the OVERDOSAGE/Human Experience section of the prescribing information for Effexor (venlafaxine), indicated for treatment of major depressive disorder. In postmarketing experience, there have been reports of overdose with venlafaxine, occurring predominantly in combination with alcohol and/or other drugs. Published retrospective studies report that venlafaxine overdosage may be associated with an increased risk of fatal outcome compared to that observed with SSRI antidepressant products, but lower than that for tricyclic antidepressants. Healthcare professionals are advised to prescribe Effexor and Effexor XR in the smallest quantity of capsules consistent with good patient management to reduce the risk of overdose.

Management of Overdosage

There is no specific antidote for venlafaxine and management is generally supportive, providing treatment for the immediate symptoms. Administration of activated charcoal can prevent absorption of the drug. Monitoring of cardiac rhythm and vital signs is indicated. Seizures are managed with benzodiazepines or other anti-convulsants. Forced diuresis, hemodialysis, exchange transfusion, or hemoperfusion are unlikely to be of benefit in hastening the removal of venlafaxine, due to the drug's high volume of distribution.[26]

Footnotes

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b Whyte I, Dawson A, Buckley N (2003). "Relative toxicity of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in overdose compared to tricyclic antidepressants". QJM. 96 (5): 369–74. PMID 12702786.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [No Authors listed]. "Acute Effectiveness of Additional Drugs to the Standard Treatment of Depression". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 23 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Goeringer K, McIntyre I, Drummer O (2001). "Postmortem tissue concentrations of venlafaxine". Forensic Sci Int. 121 (1–2): 70–5. PMID 11516890.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wellington K, Perry C (2001). "Venlafaxine extended-release: a review of its use in the management of major depression". CNS Drugs. 15 (8): 643–69. PMID 11524036.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Effexor Medicines Data Sheet". Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2006. Retrieved 17 September.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Parker G, Blennerhassett J (1998). "Withdrawal reactions associated with venlafaxine". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 32 (2): 291–4. PMID 9588310.

- ^ Rowbotham M, Goli V, Kunz N, Lei D (2004). "Venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Pain. 110 (3): 697–706. PMID 15288411.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ozyalcin S, Talu G, Kiziltan E, Yucel B, Ertas M, Disci R (2005). "The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine". Headache. 45 (2): 144–52. PMID 15705120.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayo Clinic staff (2005). "Beyond hormone therapy: Other medicines may help". Hot flashes: Ease the discomfort of menopause. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 19 August.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Schober C, Ansani N (2003). "Venlafaxine hydrochloride for the treatment of hot flashes". Ann Pharmacother. 37 (11): 1703–7. PMID 14565812.

- ^ Courtney D (2004). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and venlafaxine use in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: a systematic review of published randomized controlled trials". Can J Psychiatry. 49 (8): 557–63. PMID 15453105.

- ^ Gentile S (2005). "The safety of newer antidepressants in pregnancy and breastfeeding". Drug Saf. 28 (2): 137–52. PMID 15691224.

- ^ de Moor R, Mourad L, ter Haar J, Egberts A (2003). "[Withdrawal symptoms in a neonate following exposure to venlafaxine during pregnancy]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 147 (28): 1370–2. PMID 12892015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeVane CL. (2003). "Immediate-release versus controlled-release formulations: pharmacokinetics of newer antidepressants in relation to nausea". J Clin Psychiatry. 64 (Suppl 18): 14–9. PMID 14700450.

- ^ Mines D, Hill D, Yu H, Novelli L (2005). "Prevalence of risk factors for suicide in patients prescribed venlafaxine, fluoxetine, and citalopram". Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 14 (6): 367–72. PMID 15883980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ my therapy discussion

- ^ Adan-Manes J, Novalbos J, López-Rodríguez R, Ayuso-Mateos J, Abad-Santos F (2006). "Lithium and venlafaxine interaction: a case of serotonin syndrome". J Clin Pharm Ther. 31 (4): 397–400. PMID 16882112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Haddad P (2001). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes". Drug Saf. 24 (3): 183–97. PMID 11347722.

- ^ Fava M, Mulroy R, Alpert J, Nierenberg A, Rosenbaum J (1997). "Emergence of adverse events following discontinuation of treatment with extended-release venlafaxine". Am J Psychiatry. 154 (12): 1760–2. PMID 9396960.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Double D (1997). "Prescribing antidepressants in general practice. People may become psychologically dependent on antidepressants". BMJ. 314 (7083): 829. PMID 9081020.

- ^ Blythe D, Hackett L (1999). "Cardiovascular and neurological toxicity of venlafaxine". Hum Exp Toxicol. 18 (5): 309–13. PMID 10372752.

- ^ Mazur J, Doty J, Krygiel A (2003). "Fatality related to a 30-g venlafaxine overdose". Pharmacotherapy. 23 (12): 1668–72. PMID 14695048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banham N (1998). "Fatal venlafaxine overdose". Med J Aust. 169 (8): 445, 448. PMID 9830400.

- ^ MHRA UK (May 31st 2006). "Updated product information for venlafaxine". Safeguarding public health.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Hanekamp B, Zijlstra J, Tulleken J, Ligtenberg J, van der Werf T, Hofstra L (2005). "Serotonin syndrome and rhabdomyolysis in venlafaxine poisoning: a case report". Neth J Med. 63 (8): 316–8. PMID 16186642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Drug information

- U.S. Federal Drug Administration information on Effexor

- Efexor patient information leaflet Efexor patient information leaflet

- Effexor XR® prescribing information for healthcare professionals (pdf) (USA only)

- Detailed Patient/Parent Information on Effexor exellent

Industry pages

- The Offical website of Effexor XR The Official website of Effexor XR

Patient experiences

- Effexor petition by users detailing severe discontinuation effects and concerns

- Effexor Side Effects Patient comments.

Chemical data