Christianity in China

Christianity in China has a history going back to the Tang dynasty (8th century). Christianity in China comprises Protestants, Catholics, and a small number of Orthodox Christians. Although its lineage in China is not as ancient as the institutional religions of Taoism and Mahayana Buddhism and the social system and ideology of Confucianism, Christianity has existed in China since at least the seventh century and has gained influence over the past 200 years.[2][3]

In recent years, the number of Chinese Christians has increased significantly, particularly since the easing of restrictions on religious activity during economic reforms in the late 1970s.[4] In many parts of the People's Republic of China, the practice of religion continues to be tightly controlled by government authorities. Chinese over the age of 18 are only permitted to join officially sanctioned Christian groups registered with the government-affiliated Three-Self Patriotic Movement and Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association.[5] Official statistics show that the number of Protestants has increased to the tens of millions (from 700,000 in 1949) since the Communist Revolution. According to a survey published in 2010, there are now approximately 52 million Christians in China, including 40 million Protestants and 12 million Catholics.,[6] although some believe the actual numbers to be significantly higher. While no Protestant churches or meetings were sanctioned by the government during the Cultural Revolution, by 2006, there were over 50,000 Protestant churches and meeting places registered with the Chinese government.[7]

Much of this growth has occurred in informal networks referred to as "house churches," the proliferation of which began in the 1950s when many Chinese Catholics and Protestants began to reject state-controlled structures purported to represent them.[8] Members of such groups are now said to represent the "silent majority" of Chinese Christians and represent many diverse theological traditions.[9]

Terminology

There are various terms used for God in the Chinese language, the most prevalent being Shangdi (上帝, literally, "Highest Emperor"), used commonly by Protestants and also by non-Christians, and Tianzhu (天主, literally, "Lord of Heaven"), which is most commonly favoured by Catholics. Shen (神), also widely used by Chinese Protestants, defines the gods or generative powers of nature in Chinese traditional religions. Historically, Christians have also adopted a variety of terms from the Chinese classics as referents to God, for example Ruler (主宰) and Creator (造物主).

Terms for Christianity in Chinese include: "Protestantism" (Chinese: 基督教新教; pinyin: Jīdū jiào xīn jiào; lit. 'New Christ teaching'); "Catholicism" (Chinese: 天主教; pinyin: Tiānzhǔ jiào; lit. 'Lord of Heaven teaching'); and Eastern Orthodox Christians (Chinese: 東正教/东正教; pinyin: Dōng zhèng jiào; lit. 'Eastern Orthodox teaching'). The whole of Orthodox Christianity is named Zhèng jiào (正教). Christians in China are referred to as "Christ believers" (Chinese: 基督徒; pinyin: Jīdū tú) or "Christ teaching believers" (Chinese: 基督教徒; pinyin: Jīdū jiào tú).

Pre-modern history

Earliest documented period

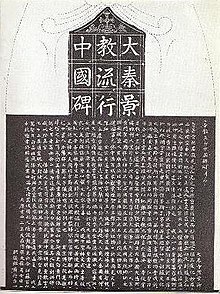

The first documentation of Christianity entering China was written on an 8th-century stone tablet known as the Nestorian Stele. It records that Christians reached the Tang dynasty capital Xian in 635 and were allowed to establish places of worship and to propagate their faith. The leader of the Christian travelers was Alopen.[10]

Some modern scholars question whether Nestorianism is the proper term for the Christianity that was practiced in China, since it did not adhere to what was preached by Nestorius. They instead prefer to refer to it as "Church of the East", a term which encompasses the various forms of early Christianity in Asia.[11]

In 845, at the height of the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, Emperor Wuzong decreed that Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism be banned, and their very considerable assets forfeited to the state.

In 986 a monk reported to the Patriarch of the East:

"Christianity is extinct in China; the native Christians have perished in one way or another; the church has been destroyed and there is only one Christian left in the land."[12]

Medieval period

The 13th century saw the Mongol-established Yuan Dynasty in China. Christianity was a major influence in the Mongol Empire, as several Mongol tribes were primarily Nestorian Christian, and many of the wives of Genghis Khan's descendants were strongly Christian. Contacts with Western Christianity also came in this time period, via envoys from the Papacy to the Mongol capital in Khanbaliq (Beijing).

Nestorianism was well established in China, as is attested by the monks Rabban Bar Sauma and Rabban Marcos, both of whom made a famous pilgrimage to the West, visiting many Nestorian communities along the way. Marcos was elected as Patriarch of the Church of the East, and Bar Sauma went as far as visiting the courts of Europe in 1287-1288, where he told Western monarchs about Christianity among the Mongols.

In 1289, Franciscan friars from Europe initiated mission work in China. For about a century they worked in parallel with the Nestorian Christians. The Franciscan mission collapsed in 1368, as the Ming Dynasty set out to eject all foreign influences.

The Chinese called Muslims, Jews, and Christians in ancient times by the same name, "Hui Hui" (Hwuy-hwuy). Crossworshipers (Christians) were called "Hwuy who abstain from animals without the cloven foot", Muslims were called "Hwuy who abstain from pork", Jews were called "Hwuy who extract the sinews". Hwuy-tsze (Hui zi) or Hwuy-hwuy (Hui Hui) is presently used almost exclusively for Muslims, but Jews were still called Lan Maou Hwuy tsze (Lan mao Hui zi) which means "Blue cap Hui zi". At Kaifeng, Jews were called "Teaou kin keaou "extract sinew religion". Jews and Muslims in China shared the same name for synagogue and mosque, which were both called "Tsing-chin sze" (Qingzhen si) "Temple of Purity and Truth", the name dated to the thirteenth century. The synagogue and mosques were also known as Le-pae sze (Libai si). A tablet indicated that Judaism was once known as "Yih-tsze-lo-nee-keaou" (israelitish religion) and synagogues known as Yih-tsze lo née leen (Israelitish Temple), but it faded out of use.[13]

It was also reported that competition with the Roman Catholic Church and Islam were also factors in causing Nestorian Christianity to disappear in China, with "controversies with the emissaries of.... Rome, and the "progress of Mohammedanism, sapped the foundations of their ancient churches."[14] The Roman Catholics also considered the Nestorians as heretical[15]

The Ming dynasty decreed that Manichaeism and Christianity were illegal and heterodox, to be wiped out from China, while Islam and Judaism were legal and fit Confucian ideology.[16] Buddhist Sects like White Lotus were also banned by the Ming.

Post-Reformation

By the 16th century, there is no reliable information about any practicing Christians remaining in China. Fairly soon after the establishment of the direct European maritime contact with China (1513), and the creation of the Society of Jesus (1540), at least some Chinese become involved with the Jesuit effort. As early as 1546, two Chinese boys became enrolled into the Jesuits' St. Paul's College in Goa, the capital of Portuguese India. It is one of these two Christian Chinese, known as Antonio, who accompanied St. Francis Xavier, a co-founder of the Society of Jesus, when he decided to start missionary work in China. However, Xavier was not able to find a way to enter the Chinese mainland, and died in 1552 on Shangchuan island off the coast of Guangdong.

It was the new regional manager ("Visitor") of the order, Alessandro Valignano, who, on his visit to Macau in 1578-1579 realized that Jesuits weren't going to get far in China without a sound grounding in the language and culture of the country. He founded St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau) and requested the Order's superiors in Goa to send a suitably talented person to Macau to start the study of Chinese.

In 1582, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, introducing Western science, mathematics, and astronomy. One of these missionaries was Matteo Ricci.

In the early 18th century, the Chinese Rites controversy, a dispute within the Roman Catholic Church, arose over whether Chinese folk religion rituals and offerings to their ancestors constituted idolatry. The Pope ultimately ruled against tolerating the continuation of these practices among Chinese Roman Catholic converts. Prior to this, the Jesuits had enjoyed considerable influence at court, but with the issuing of the papal bull, the emperor circulated edicts banning Christianity. The Catholic Church did not reverse this stance until 1939, after further investigation and a clarified ruling by Pope Pius XII.

17th to 18th centuries

Further waves of missionaries came to China in the Qing (or Manchu) dynasty (1644–1911) as a result of contact with foreign powers. Russian Orthodoxy was introduced in 1715 and Protestants began entering China in 1807.

The Qing dynasty Yongzheng emperor was firmly against Christian converts among his own Manchu people. He warned them that the Manchus must follow only the Manchu way of worshipping Heaven since different peoples worshipped Heaven differently.[17] Yongzheng stated: "The Lord of Heaven is Heaven itself. . . . In the empire we have a temple for honoring Heaven and sacrificing to Him. We Manchus have Tiao Tchin. The first day of every year we burn incense and paper to honor Heaven. We Manchus have our own particular rites for honoring Heaven; the Mongols, Chinese, Russians, and Europeans also have their own particular rites for honoring Heaven. I have never said that he [Urcen, a son of Sun] could not honor heaven but that everyone has his way of doing it. As a Manchu, Urcen should do it like us."[18]

Modern age

Missionary expansion (1807–1900)

140 years of Protestant missionary work began with Robert Morrison, arriving in Macau on 4 September 1807.[19] Morrison produced a Chinese translation of the Bible. He also compiled a Chinese dictionary for the use of Westerners. The Bible translation took twelve years and the compilation of the dictionary, sixteen years.

Under the "fundamental laws" of China, one section is titled "Wizards, Witches, and all Superstitions, prohibited." The Jiaqing Emperor in 1814 A.D. added a sixth clause in this section with reference to Christianity. It was modified in 1821 and printed in 1826 by the Daoguang Emperor. It sentenced Europeans to death for spreading Christianity among Han Chinese and Manchus (tartars). Christians who would not repent their conversion were sent to Muslim cities in Xinjiang, to be given as slaves to Muslim leaders and beys.[20] Some hoped that the Chinese government would discriminate between Protestantism and the Catholic Church, since the law was directed at Rome, but after Protestant missionaries in 1835-6 gave Christian books to Chinese, the Daoguang Emperor demanded to know who were the "traitorous natives in "Canton who had supplied them with books." The foreign missionaries were strangled or expelled by the Chinese.[21]

The pace of missionary activity increased considerably after the First Opium War in 1842. Christian missionaries and their schools, under the protection of the Western powers, went on to play a major role in the Westernization of China in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Liang Fa (梁發, Leung Fat in Cantonese) worked in a printing company in Guangzhou in 1810 and came to know Robert Morrison, who translated the Bible to Chinese and needed printing of the translation. When William Milne arrived at Guangzhou in 1813 and worked with Morrison on translation of the Bible, he also came to know Liang Fa. Liang was baptized by Milne in 1816. In 1821, Liang was ordained by Morrison, thus becoming a missionary of the London Missionary Society and the first Chinese Protestant minister and evangelist.

During the 1840s, Western missionaries spread Christianity rapidly through the coastal cities that were open to foreign trade; the bloody Taiping Rebellion was connected in its origins to the influence of some missionaries on the leader Hong Xiuquan, who has since been hailed as a heretic by most Christian groups, but as a proto-communist peasant militant by the Chinese Communist Party. The Taiping Rebellion was a large-scale revolt against the authority and forces of the Qing Government. It was conducted from 1850 to 1864 by an army and civil administration led by heterodox Christian convert Hong Xiuquan. He established the "Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace" with the capital Nanjing and attained control of significant parts of southern China, at its height ruling over about 30 million people. The theocratic and militaristic regime instituted several social reforms, including strict separation of the sexes, abolition of foot binding, land socialization, suppression of private trade, and the replacement of Confucianism, Buddhism and Chinese folk religion by a form of Christianity, holding that Hong Xiuquan was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. The Taiping rebellion was eventually put down by the Qing army aided by French and British forces. With an estimated death toll of between 20 and 30 million due to warfare and resulting starvation, this civil war ranks among history's deadliest conflicts. Mao Zedong viewed the Taiping as early heroic revolutionaries against a corrupt feudal system.[22]

Christians in China established the first modern clinics and hospitals,[23] and provided the first modern training for nurses. Both Roman Catholics and Protestants founded numerous educational institutions in China from the primary to the university level. Some of the most prominent Chinese universities began as religious-founded institutions. Missionaries worked to abolish practices such as foot binding,[24] and the unjust treatment of maidservants, as well as launching charitable work and distributing food to the poor. They also opposed the opium trade[3] and brought treatment to many who were addicted. Some of the early leaders of the Chinese Republic, such as Sun Yat-sen were converts to Christianity and were influenced by its teachings.[25]

By the early 1860s the Taiping movement was almost extinct, Protestant missions at the time were confined to five coastal cities. By the end of the century, however, the picture had vastly changed. Scores of new missionary societies had been organized, and several thousand missionaries were working in all parts of China. This transformation can be traced to the Unequal Treaties which forced the Chinese government to admit Western missionaries into the interior of the country, the excitement caused by the 1859 Awakening in Britain and the example of J. Hudson Taylor (1832–1905). Taylor (Plymouth Brethren (Open Brethren)) arrived in China in 1854. Historian Kenneth Scott Latourette wrote that "Hudson Taylor was, ...one of the greatest missionaries of all time, and ... one of the four or five most influential foreigners who came to China in the nineteenth century for any purpose...". The China Inland Mission was the largest mission agency in China and it is estimated that Taylor was responsible for more people being converted to Christianity than at any other time since Paul the Apostle brought Christian teaching to Europe. Out of the 8,500 Protestant missionaries that were at one time at work in China, 1000 of them were from the CIM.[19] It was Dixon Edward Hoste, the successor to Hudson Taylor, who originally expressed the self-governing principles of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, at the time he was articulating the goal of the China Inland Mission to establish an indigenous Chinese church that was free from foreign control.

It was not always this way. Back in the era of the emperors, there were charitable organizations for virtually every social service: burial of the dead, care of orphans, provision of food for the hungry. The wealthiest in every community—typically, the merchants—were expected to give food, medicine, clothing, and even cash to those in need. According to Caroline Reeves, a historian at Emmanuel College in Boston, that began to change with the arrival of American missionaries in the late 19th century. "One of the reasons they gave for being there was to help the poor Chinese," she says. "Because of that need to justify their existence in China, they downplayed China's own charity. That attitude, that denial of reality, is still very strong today."[citation needed]

By 1865 when the China Inland Mission began, there were already thirty different Protestant groups at work in China,[26] however the diversity of denominations represented did not equate to more missionaries on the field. In the seven provinces in which Protestant missionaries had already been working, there were an estimated 204 million people with only 91 workers, while there were eleven other provinces in inland China with a population estimated at 197 million, for whom absolutely nothing had been attempted.[27] Besides the London Missionary Society, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, there were missionaries affiliated with Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Episcopalians, and Wesleyans. Most missionaries came from England, the United States, Sweden, France, Germany, Switzerland, or the Netherlands.[28]

In addition to the publication and distribution of Christian literature and Bibles (see:Chinese Bible Translations), the Protestant Christian missionary movement in China furthered the dispersion of knowledge with other printed works of history and science. As the missionaries went to work among the Chinese, they established and developed schools and introduced the latest techniques in medicine[28] (see:Medical missions in China). The mission schools were viewed with some suspicion by the traditional Chinese teachers, but they differed from the norm by offering a basic education to poor Chinese, both boys and girls, who had no hope of learning at a school before the days of the Chinese Republic.[29]

The Boxer Uprising was in part a reaction against Christianity in China. Christianity was prevalent among bandits in Shandong, China. In 1895, the Manchu Yuxian, a magistrate in the province, acquired the help of the Big Swords Society in fighting against Bandits. The Big Swords practiced heterodox practices, however, they were not bandits and were not seen as bandits by Chinese authorities. The Big Swords relentlessly crushed the bandits, but the bandits converted to Catholic Christianity, because it made them legally immune to prosecution and under the protection of the foreigners. The Big Swords proceeded to attack the bandit Catholic churches and burn them.[30] Yuxian only executed several Big Sword leaders, but did not punish anyone else. More secret societies started emerging after this.[31]

In Pingyuan, the site of another insurrection and major religious disputes, the county magistrate noted that Chinese converts to Christianity were taking advantage of their bishop's power to file false lawsuits which, upon investigation, were found groundless.[32]

Popularity and indigenous growth (1900–1925)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

The Qing dynasty Imperial government permitted Christian missionaries to enter and proselytize in Tibetan lands, which weakened the control of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas, who refused to give allegiance to the Chinese. The Tibetan Lamas were alarmed and jealous of Catholic missionaries converting natives to Roman Catholicism. During the 1905 Tibetan Rebellion the Tibetan Buddhist Gelug Yellow Hat sect led a Tibetan revolt, with Tibetan tribesmen being led by Lamas to kill and attack Chinese officials, western Christian missionaries and native Christian converts, the revolt was aimed at expelling Christians and overthrowing Chinese rule. The Lamas responded to the Christian missionaries by massacring the missionaries and native converts to Christianity. The Lamas besieged Bat'ang, burning down the mission chapel, and killing two foreign missionaries, Père Mussot and Père Soulié. The Chinese Amban's Yamen was surrounded, the Chinese General, Wu Yi-chung, was shot dead in the Yamen by the Lama's forces. The Chinese Amban Feng and Commandant in Chief Li Chia-jui managed to escape by scattering Rupees (money) behind them, which the Tibetans proceeded to try to pick up. The Ambans reached Commandant Lo's place, but the 100 Tibetan troops serving under the Amban, armed with modern weaponry, mutinied when news of the revolt reached them. The Tibetan Lamas and their Tibetan followers besieged the Chinese Commandant Lo's palace along with local Christian converts. In the palace, they killed all Christian converts, both Chinese and Tibetan.[33]

Indigenous Christian evangelistic work started in China in the late 1800s. This work involved both the clergy and those that were not in the clergy. Dr. Man-Kai Wan, 尹文階 (1869–1927) was one of the first Chinese doctors of Western medicine in Hong Kong, the inaugural Chairman of the Hong Kong Chinese Medical Association 香 港 中 華 醫 學 會 (1920–1922, forerunner of Hong Kong Medical Association), and a secondary school classmate of Sun Yat-Sen (孫中山, 1866–1925, the leader of Kuomintang 中國國民黨, Chinese Nationalist Party) in The Government Central College (中央書院, currently known as Queen's College, Hong Kong皇仁書院) in Hong Kong. Wan and Sun graduated from secondary school together in 1886. Dr. Wan was also the Chairman of the Board of a Christian newspaper called “Great Light Newspaper” (大光報) that was distributed in Hong Kong and China. Dr. Sun, a Christian (baptized in Hong Kong by an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States), had written for this newspaper. The father-in-law of Dr. Wan was Fung-Chi Au (區鳳墀, 1847–1914), who was Sun’s teacher of Chinese literature, Secretary of the Hong Kong Department of Chinese Affairs (香港華民政務司署總書記), the manager of Kwong Wah Hospital (廣華醫院) for its 1911 opening, and an Elder of To Tsai Church (道濟會堂), which was founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888 and located at 75 Hollywood Road, Mid-levels (半山區), Hong Kong. Sun attended this church while he studied Medicine. Due to its growth, this church erected a large building in 1926 and was renamed Hop Yat Church (合一堂).

Following the 1910 World Missionary Conference in Glasgow, world mission leadership energetically promoted what they called "indigenization," that is, turning leadership over to local Christian leaders. The Chinese National YMCA was the first to do so. In the 1920s, a group of church leaders formed the National Christian Council to coordinate interdenominational activity. Among the leaders were the Cheng Jingyi, who had excitied the Glasgow Conference with his call for a non-denominational church, and David Z.T. Yui, of the Chinese YMCA. At this time the way was prepared for the Church of Christ in China, a unified, that is, non-denominational Church.[34]

Era of national and social change, the Japanese occupation (1925–1949)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2014) |

As a result of being separated due to World War II, Christian churches and organizations had their first experience with autonomy from the Western-guided structures of the missionary church organizations. Some scholars suggest this helped lay the foundation for the independent denominations and churches of the post-war period and the eventual development of the Three-Self Church and the CCPA.

After the end of the war, the Chinese Civil War began in earnest, which had an effect on the rebuilding and development of the churches after the close of Japanese occupation.

Communist rule

The People's Republic of China was established in October 1949 by the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong. Under Communist ideology, religion was discouraged by the state and Christian Missionaries left the country in what was described by Phyllis Thompson of the China Inland Mission as a "reluctant exodus", leaving the indigenous churches to do their own administration, support, and propagation of the faith. The Chinese Protestant church entered the communist era having made significant progress toward self-support and self-government. Though Chinese rulers had traditionally sought to regulate organized religion and the CPC would continue the practice, Chinese Christians had gained experience in the art of accommodation in order to protect its members. Significantly, while the Chinese Communist Party was hostile to religion in general, they did not seek to systematically destroy religion for the most part as long as the religious organizations were willing to submit to the direction of the Chinese state. Many Protestants were willing to accept such accommodation and were permitted to continue religious life in China under the name Three-Self Patriotic Movement. Catholics, on the other hand, with their allegiance to the Holy See, could not submit to the Chinese state as their Protestant counterparts did, notwithstanding the willingness of the Vatican to compromise in order to remain on Chinese mainland—the papal nuncio in China did not withdraw to Taiwan like other western diplomats, for example. Consequently, the Chinese state organized Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association that operates without connection to Vatican and the Catholics who continued to acknowledge the authority of the Pope were subject to persecution.

From 1966 to 1976 during the Cultural Revolution, the expression of religious life in China was effectively banned, including even the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. The growth of the Chinese house church movement during this period was a result of all Chinese Christian worship being driven underground for fear of persecution. To counter this growing trend of "unregistered meetings", in 1979 the government officially restored the Three-Self Patriotic Movement after thirteen years of non-existence,[19] and in 1980 the China Christian Council (CCC) was formed.

In 1993 there were 7 million members of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement with 11 million affiliated, as opposed to an estimated 18 million and 47 million "unregistered" Protestant Christians respectively. According to a survey done by China Partner (Founder Werner Burklin), there are now between 39-41 million Protestant Christians in China. The survey was done with 7.400 individuals in 2007-08 in all 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions except Tibet. Another survey done with 4.500 individuals by the East China Normal University in Shanghai came to the same result.

Persecution of Christians in China has been sporadic. The most severe times were during the Cultural Revolution. Believers were arrested and imprisoned and sometimes tortured for their faith.[35] Bibles were destroyed, churches and homes were looted, and Christians were subjected to humiliation.[35] Several thousand Christians were known to have been imprisoned between 1983-1993.[35] In 1992 the government began a campaign to shut down all of the unregistered meetings. However, government implementation of restrictions since then has varied widely between regions of China and in many areas there is greater religious liberty.[35] Independent churches and evangelical denominations have broadened the appeal of Protestantism, especially in rural China. Although outside observers thought that the Cultural Revolution had ended Christianity in China, Christianity in all its variety had taken root and possessed the strength to survive decades of hostility and persecution.

Catholic underground church in China, i.e. those who do not belong to the official Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, remains theoretically (and occasionally, in reality) subject to persecution today. In practice, however, the Vatican and the Chinese State have been, at least unofficially, accommodating each other for some time. While some bishops who joined the CPCA in its early years have been condemned and even excommunicated, the entire organization has never been declared schismatic by the Vatican and, at present, its bishops (many of whom sought and received papal approval after their appointment, even if they are strictly CPCA appointees) are even invited to church synods like other Catholic leaders. What is more, many underground clergy and laymen are also active in the CPCA as well. Still, there are periods of discomfort between Vatican and the CPCA: Pope Benedict XVI condemned CPCA leaders as "persons who are not ordained, and sometimes not even baptised", who "control and take decisions concerning important ecclesial questions, including the appointment of Bishops"; Chinese state indeed continues to appoint bishops and dictate CPCA policy (most notably on abortion and artificial contraception) without consulting the Vatican and punishes outspoken dissenters. In one notable case that drew international attention, Thaddeus Ma Daqin, the auxiliary bishop of Shanghai whom both the Vatican and Chinese state agreed as the successor to the elderly Aloysius Jin Luxian, the CPCA bishop of Shanghai (whom Vatican also recognized as the coadjutor bishop), was arrested and imprisoned after publicly resigning from his CPCA positions in 2012, which was considered a challenge to the state control over the Catholic Church in China.

Contemporary People's Republic of China

The current number of Christians in China is disputed. The most recent official census enumerated 4 million Roman Catholics and 10 million Protestants. Other studies have suggested that there are roughly 52 million Christians in China, of which 40 million are Protestants and 12 million are Catholics; these are seen as the most common and reliable figures.[36][37]

Official organizations

The Three-Self Patriotic Movement and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association are affiliated with the Chinese government and impose regulations on Christian gatherings, all of which are required to be registered under their auspices.

House churches

Many Christians hold meetings outside of the jurisdiction of these organizations. Such groups, usually known as house churches often avoid registration with the government and are illegal. While there has been continuous persecution of Chinese Christians throughout the twentieth century, particularly during the Cultural Revolution, there has been increasing tolerance of house churches since the late 1970s.

Orthodox Christianity

There are a small number of adherents of Russian Orthodoxy in northern China, predominantly in Harbin. The first mission was undertaken by Russians in the 17th century. Orthodox Christianity is also practiced by the small Russian ethnic minority in China. The Church operates relatively freely in Hong Kong (where the Ecumenical Patriarch has sent a metropolitan, Bishop Nikitas and the Russian Orthodox parish of St Peter and St Paul resumed its operation) and Taiwan (where archimandrite Jonah George Mourtos leads a mission church).

Religious practice

Officials from the Three-Self Church count around 20 million citizens worshipping in official churches. There are about 50,000 TS churches and 18 TS theological schools.

The Catholic Patriotic Association reports that 5.3 million persons worship in its churches. According to official sources, the government-sanctioned CPA has more than 70 bishops, nearly 3,000 priests and nuns, 6,000 churches and meeting places, and 12 seminaries. There are thought to be approximately 40 bishops operating "underground," some of whom are in prison or under house arrest. During the reporting period, at least three bishops were ordained with papal approval. In September 2007 the official media reported that Liu Bainian, CPA vice president, stated that the young bishops were to be selected to serve dioceses without bishops and to replace older bishops. Of the 97 dioceses in the country, 40 reportedly did not have an acting bishop in 2007, and more than 30 bishops were over 80 years of age.[38]

On August 30, 2010, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints revealed its on-going efforts to negotiate with the Chinese authorities to regularize its activities in China. The LDS Church has had expatriate members worshiping in China for a few decades previous to this, but with restrictions.[39]

Religious restrictions

The government restricts legal religious practice to government-sanctioned organizations and registered religious groups and places of worship, through the Three-Self Church and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. Government authorities limit proselytism, particularly by foreigners and unregistered religious groups, but permit proselytism in state-approved religious venues and private settings.[38]

In 2008, the Government's repression of religious freedom intensified in some areas. Unregistered Protestant religious groups in Beijing reported intensified harassment from government authorities in the lead up to the 2008 Summer Olympic Games. Media and China-based sources reported that municipal authorities in Beijing closed some house churches or asked them to stop meeting during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. During the reporting period, officials detained and interrogated several foreigners about their religious activities and in several cases alleged that the foreigners had engaged in "illegal religious activities" and cancelled their visas. Media reported that the total number of expatriates expelled by the government due to concerns about their religious activities exceeded one hundred.[38]

"Underground" Roman Catholic clergy faced repression, in large part due to their avowed loyalty to the Vatican, which the government accused of interfering in the country's internal affairs. The government continued to repress groups that it designated as "cults", which included several Christian groups.[38]

Demographics and geography

Although a number of factors—the vast Chinese population and the characteristic Chinese approach to religion among others—contribute to a difficulty to obtain empirical data on the number of Christians in China, a series of surveys and estimates have been conducted and published by different agencies.

- In 2000, the People's Republic of China government census enumerated 4 million Chinese Catholics and 10 million Protestants.[40] An older report enumerated 13 millions, or 1% of the population.[41] In the same period the Chinese Embassy reported a number of 10 million (0.75%).[42]

- In October 2007 two surveys were conducted to count the number of Christians in China. One of them was held by Protestant missionary Werner Burklin, the other one by Liu Zhongyu from East China Normal University in Shanghai. The surveys were conducted independently and during different periods, but they reached the same results.[36][37] According to these studies, there were approximately 54 million Christians in China, of whom 39 million were Protestants and 14 million were Catholics.[36][37][43]

- In a December 2011 report, The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life estimated over 67 million Christians in China.[44][45]

- A survey published in 2010 reported 33 million Christians, of which 30 million are Protestants and 3 million Catholics.[6]

A relatively large proportion of Christians are concentrated in south-eastern coastal provinces: Fujian, Zhejiang and Anhui, but also Henan hosts a significant number of Christians. Hebei has a concentration of Catholics and is also home to the town of Donglu, site of an alleged Marian apparition and pilgrimage center.

Gerda Wielander (2013) has noticed how estimates of the number of Christians in China that have been spread by Western media may be highly inflated.[48] Citing one of the aforementioned surveys, she says that the actual number of Christians is around 30 millions.[48] Missionary researcher Tony Lambert has highlighted that a groundless estimate of "one hundred million Chinese Christians" was already being spread by American Christian media in 1983, and has been furtherly exaggerated, through a chain of misquotations, in the 2000s.[49]

Hong Kong

Christianity has been practiced in Hong Kong since 1841. Of about 843,000 Christians in Hong Kong, most of them are Anglican or Roman Catholic.

Macau

Catholic missionaries were the first to arrive in Macau. In 1535, Portuguese traders obtained the rights to anchor ships in Macau's harbours and to carry out trading activities, though not the right to stay onshore.[50] Around 1552–1553, they obtained temporary permission to erect storage sheds onshore, in order to dry out goods drenched by sea water;[51] they soon built rudimentary stone houses around the area now called Nam Van. In 1576, Pope Gregory XIII established the Roman Catholic Diocese of Macau.[52] In 1583, the Portuguese in Macau were permitted to form a Senate to handle various issues concerning their social and economic affairs under strict supervision of the Chinese authority,[53] but there was no transfer of sovereignty.[54] Macau prospered as a port but was the target of repeated failed attempts[55] by the Dutch to conquer it in the 17th century.

Protestants record that Tsae A-Ko was the first known Chinese Protestant Christian.[56] He was baptized by Robert Morrison at Macau about 1814.

Shanxi

Christianity is a minority in Shanxi province, but there are more Catholics than Buddhists.[57] In the countryside there are a number of Catholic villages, for instance, Liuhecun is a village with a Catholic majority.[58] The province has a house church network with an estimated 50,000 adherents.[59] 10 leading figures have been sentenced in 2009.[59] The Shouters are present in the province.[60] The number of Protestants was 30,000 in 1949.[61] It is much larger now.[61] It has relatively large freedom.[58]

Historically, Catholicism entered the province in the early 1600s and Protestant missionaries arrived in the 1860s. During the Boxer Uprising, a wave of anti-foreign and anti-Christian violence killed thousands of Protestant and Catholic Christians and missionaries, mostly notoriously in the Taiyuan msssacre. Those killed in the province included 9000 Catholics, including three bishops (Gregor Grassi, Franz Fogolla and Antonin Fantosati).[62]

There are six Roman Catholic dioceses in Shanxi: Archdiocese of Taiyuan, Archdiocese of Datong, Archdiocese of Fenyang, Archdiocese of Hongdong, Archdiocese of Lu’an, Archdiocese of Shuozhou, and Archdiocese of Yuci.

Autonomous regions

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region

Tibet Autonomous Region

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

Predominantly Muslim, very few Uygur are known to be Christian. In 1904, George Hunter with the CIM opened the first mission station for CIM in Xinjiang. But already in 1883 the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden started mission in the area around Kashgar and built several missionary stations. By the 1930s there existed some churches among this people, but because of violent persecution the churches were destroyed and the believers were scattered.[63]

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

Though the Hui people live in nearly every part of China, they make up about 30% of the population of Ningxia. They are almost entirely Muslim and very few are Christian.

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region

Rapid church growth is reported to have taken place among the Zhuang people in the early 1990s.[35] Though still predominantly Buddhist and animistic, the region of Guangxi was first visited in 1877 by Protestant missionary Edward Fishe of the CIM. He died the same year.

International interest

In large, international cities such as Beijing,[64] foreign visitors have established Christian church communities which meet in public establishments such as hotels. These churches and fellowships, however, are typically restricted only to holders of non-Chinese passports.

American evangelist Billy Graham visited in China in 1988 with his wife, Ruth, and it was a homecoming for her since she had been born in China to missionary parents, L. Nelson Bell and his wife, Virginia.[65]

Since the 1980s, American officials visiting China have on multiple occasions visited Chinese churches, including President George W. Bush, who attended one of Beijing's five officially-recognized Protestant churches during a November 2005 Asia tour,[66] and the Kuanjie Protestant Church in 2008.[67][68] During an official visit to Beijing for the Beijing Olympic Games, Australian Prime Minister of Kevin Rudd with his wife Therese attended the Northern Cathedral, Beijing, for Sunday services in August 2008.[69] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice attended Palm Sunday services in Beijing in 2005.

During the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, three American Christian protesters were deported from China after a demonstration at Tiananmen Square,[70][71][72] and eight Dutch Christians were stopped after attempting to sing in chorus.[73] Pope Benedict XVI urged China to be open to Christianity, and said that he hoped the Olympic Games would offer an example of coexistence among people from different countries.[74]

See also

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

- Bibliography of Christianity in China

- Church of the East

- Jesuit China missions

- Xu Guangqi

- Chinese Rites controversy

- Protestant missions in China 1807–1953

- Historical Bibliography of the China Inland Mission

- Christianity in India

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in the People's Republic of China

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Chinese New Hymnal

- Chinese Union Version of the Bible

- List of Protestant theological seminaries in the People's Republic of China

- Religion in China

- Manchurian revival

References

- Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- Burgess, Alan (1957). The Small Woman. ISBN 1-56849-184-0.

- Gulick, Edward V. (1975). Peter Parker and the Opening of China. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 95, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1975).

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1929). A History of Christian Missions in China.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30780-8.

- Taylor, James Hudson (1868). China's Spiritual Need and Claims (Third Edition). London: James Nisbet.

- Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 13.

- Thompson, Phyllis. The Reluctant Exodus. 1979. Singapore: OMF Books.

- Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635-1800, (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 4 China), Edited by Nicolas Standaert, Brill: Leiden - Boston 2000, 964 pp., ISBN 978-9004114319

- Handbook of Christianity in China. Volume Two: 1800 - present. (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 4 China), Edited by R. G. Tiedemann, Brill: Leiden - Boston 2010), 1050 pp., ISBN 978-90-04-11430-2

- Gerda Wielander. Christian Values in Communist China. Routledge, 2013. ISBN 0415522234

Notes

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China, by Robert Samuel Maclay, a publication from 1861, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Missionary herald, Volume 17, by American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a publication from 1821, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Missionary herald, Volume 17, by American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a publication from 1821, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1, a publication from 1863, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General, a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113, by Making of America Project, a publication from 1914, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113, by Making of America Project, a publication from 1914, now in the public domain in the United States.

- ^ Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto, Canada. pp. 108–109

- ^ Daniel H. Bays. A New History of Christianity in China. (Chichester, West Sussex ; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, Blackwell Guides to Global Christianity, 2012). ISBN 9781405159548.

- ^ a b Austin, Alvyn (2007). China’s Millions: The China Inland Mission and Late Qing Society. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- ^ Aikman, David. Jesus in Beijing: How Christianity is Transforming China and Changing the Global Balance of Power. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing (2003), pp. 7-8.

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.165

- ^ a b 2010 Chinese Spiritual Life Survey conducted by Dr. Yang Fenggang, Purdue University’s Center on Religion and Chinese Society. Statistics published in: Katharina Wenzel-Teuber, David Strait. People’s Republic of China: Religions and Churches Statistical Overview 2011. Religions & Christianity in Today's China, Vol. II, 2012, No. 3, pp. 29-54, ISSN: 2192-9289.

- ^ Lambert, Tony. China's Christian Millions. Oxford: Monarch Books (2006), pp. 18-19.

- ^ Goossaert, Vincent and David A. Palmer. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (2011), pp. 380-387.

- ^ Hunter, Alan and Kim-Kwong Chan. Protestantism in Contemporary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1993), p. 178.

- ^ Ding, Wang (2006). "Remnants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval ages". Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Hofrichter, Peter L. (2006). "Preface". Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Keung. Ching Feng. p. 235.

- ^ Chinese and Japanese repository of facts and events in science, history and art, relating to Eastern Asia, Volume 1. s.n. 1863. p. 18. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 474. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ The Chinese repository, Volume 13. Printed for the proprietors. 1844. p. 475. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF). The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 15. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-8047-4684-2. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

In his indictment of Sunu and other Manchu nobles who had converted to Christianity, the Yongzheng emperor reminded the rest of the Manchu elite that each people had its own way of honoring Heaven and that it was incumbent upon Manchus to observe Manchu practice in this regard:

- ^ Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 0-8047-4684-2. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

The Lord of Heaven is Heaven itself. . . . In the empire we have a temple for honoring Heaven and sacrificing to Him. We Manchus have Tiao Tchin. The first day of every year we burn incense and paper to honor Heaven. We Manchus have our own particular rites for honoring Heaven; the Mongols, Chinese, Russians, and Europeans also have their own particular rites for honoring Heaven. I have never said that he [Urcen, a son of Sunu] could not honor heaven but that everyone has his way of doing it. As a Manchu, Urcen should do it like us.

- ^ a b c Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.164

- ^ Robert Samuel Maclay (1861). Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China. Carlton & Porter. p. 336. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Robert Samuel Maclay (1861). Life among the Chinese: with characteristic sketches and incidents of missionary operations and prospects in China. Carlton & Porter. p. 337. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ God's Chinese Son, Jonathan Spence, 1996

- ^ Gulick, Edward V. (1975). Peter Parker and the Opening of China. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 95, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1975)., pp. 561-562

- ^ Burgess, Alan (1957). The Small Woman. ISBN 1-56849-184-0., pp. 47

- ^ Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 13., p. 151-178

- ^ Spence (1991), p. 206

- ^ Taylor (1865),

- ^ a b Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30780-8., p. 206

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for modern China. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30780-8., p. 208

- ^ Paul A. Cohen (1997). History in three keys: the boxers as event, experience, and myth. Columbia University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-231-10651-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Paul A. Cohen (1997). History in three keys: the boxers as event, experience, and myth. Columbia University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-231-10651-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Lanxin Xiang (2003). The origins of the Boxer War: a multinational study. Psychology Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-7007-1563-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General (1904). East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4. Printed for H. M. Stationery Off., by Darling. p. 17. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daniel H. Bays. A New History of Christianity in China. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)., pp. 110-111.

- ^ a b c d e Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.168

- ^ a b c Mark Ellis: China Survey Reveals Fewer Christians than Some Evangelicals Want to Believe ASSIST News Service, October 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c Mark Ellis: New China survey reveals fewer Christians than most estimates Christian Examiner, November 2007.

- ^ a b c d See U.S. State Department "International Religious Freedom Report 2008"

- ^ "Church in Talks to "Regularize" Activities in China" (Press release). August 30, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ "China in Brief". china.org.cn. 2000-07-13. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Survey finds 300m China believers". BBC News. 2007-02-07. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ "China Refutes Distortions about Christianity (date unclear)". China-embassy.org. 2003-10-23. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "CIA - The World Factbook - China". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life: "Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population - Spotlight on China" December 19, 2011

- ^ The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life: "Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population - Appendix C: Methodology for China" December 19, 2011

- ^ Survey: Over 23 million Christians in China.

- ^ Survey: Over 23 million Christians in China.

- ^ a b Wieland, 2013. p. 3

- ^ Tony Lambert, Counting Christians in China: a cautionary report. International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 1/1/2003, p. 1

- ^ Fung, 5–6.

- ^ Fung, 7.

- ^ "The entry "Catholic" in Macau Encyclopedia" (in Chinese). Macau Foundation. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ <Historical figures of Macau> by CCTV.

- ^ "The entry "Macau history" in Macau Encyclopedia" (in Chinese). Macau Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ History of the Qing (清史稿)

- ^ Horne (1904), chapter 5

- ^ http://www.vnc.nl/popup.php?item=items%2Fsteden%2Ftaiyuan.php [dead link]

- ^ a b http://www.therecord.com.au/site/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1855&Itemid=28

- ^ a b http://www2.igfm.de/VR-China-Zehn-Hauskirchenleiter-zu-langen-Haftstrafen-und-Zwang.1372.0.html

- ^ http://www.chinapolitik.de/studien/china_analysis/china_geheimgesellschaften.pdf

- ^ a b http://www.prayforchina.com/province/Shaanxi.htm

- ^ http://www.kath-info.de/ragueneau.html

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick (2001). Operation World. London: Paternoster. p.167

- ^ "BICF". BICF. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Billy Graham: an appreciation: wherever one travels around the world, the names of three Baptists are immediately known and appreciated--Jimmy Carter, Billy Graham and Martin Luther King, Jr. One is a politician, one an evangelist, and the other was a civil rights leader. All of them have given Baptists and the Christian faith a good reputation. (Biography)". Baptist History and Heritage. June 22, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ View all comments that have been posted about this article. (2005-11-19). "Bush Attends Beijing Church, Promoting Religious Freedom". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "President Bush Visited Officially Staged Church Service; House Church Pastor Hua Huiqi Arrested and Escaped from Police Custody". China Aid. 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ "Bush visits controversial Beijing church". Beijing News. 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (2008-08-07). "Beijing police stop protest by U.S. Christians". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Schou, Solvej (2008-08-08). "Protesters describe removal from Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-08-08.[dead link]

- ^ Carlson, Mark (2008-08-07). "U.S. Demonstrators Taken From Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ "Three Protesters Dragged Away From Tiananmen Square". Epoch Times. 2008-08-07. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Petroff, Daniela (2008-08-07). "U.S. Demonstrators Taken From Tiananmen Square". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-08-08.[dead link]

Further reading

- General studies and guides

- Daniel H. Bays. A New History of Christianity in China. Chichester, West Sussex ; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 2012. ISBN 9781405159548.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Alan Hunter and Kim-Kwong Chan. Protestantism in Contemporary China. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Studies in Ideology and Religion, 1993). ISBN

- Richard Madsen. China's Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society. (Berkeley: University of California Press, Comparative Studies in Religion and Society, 1998). ISBN 0520213262.

- Nicolas Standaert. ed., Handbook of Christianity in China Volume One:635-1800. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, Handbook of Oriental Studies Section Four, China, 2001). ISBN 9004114319.

- Nicolas Standaert and R.G. Tiedemann. ed., Handbook of Christianity in China: Volume Two 1800-Present. Brill Academic, 2009). ISBN 9789004114302. Google Book

- Stephen Uhalley and Xiaoxin Wu. ed., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future. (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, East Gate Book, 2001). ISBN 0765606615. Google Book

- Thematic studies

- The Church of the Tang Dynasty, John Foster, SPCK, London, 1939

- The Lost Churches of China, Leonard M. Outerbridge, Westminster Press, Philadelphia, 1952

- Tsui, Ambrose Pui Ho (1992). The principle of hou: A source for Chinese Christian ethics (M.A. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

{{cite thesis}}: External link in|title= - The Story of Mary Liu, Edward Hunter, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1956

- Come Wind, Come Weather, Leslie Lyall, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1956

- Red Sky at Night, Leslie Lyall, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1961

- Christianity in China, George N. Patterson, World Books, London, 1969

- The Cross and the Lotus, Lee Shiu Keung, Christian Study Centre on Chinese Religion and Culture, Hong Kong, 1971

- Decision for China, Paul T. K. Shi, St John's University Press, N.Y., 1971

- The Jesus Family in China, D. Vaughan Rees, Paternoster Press, Exeter, 1973

- Christians and China, V. Hayward, Christian Journals Ltd, Belfast, 1974

- Nathan Sites: An Epic of the East, Sarah Moore Sites, Revell, New York, 1912

- The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, Jonathan D. Spence, New York, 1984

- Jesus in Beijing, David Aikman, Regnery Publishing Inc., Washington D.C., 2003

- China's Christian Millions (New Edition, Fully Revised and Updated) Lambert, Tony (2006)

- Counting Christians in China: a cautionary report.: An article from: International Bulletin of Missionary Research Lambert, Tony(2005)

- The Resurrection of the Chinese Church Lambert, Tony(1994)

- The Believing Heart, C.S. Song, Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999.

- Theology from the Womb of Asia, C.S. Song, Maryknoll: Orbis, 1986.

- Tell Us Our Names, C.S. Song, Maryknoll: Orbis, 1984

- Third Eye Theology, C.S. Song, Maryknoll: Orbis, 1979

- What Has Jerusalem to Do With Beijing? K. K. Yeo, Harrisburg: Trinity: 1998.

- William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary, Larry Clinton Thompson, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2009

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, "The Ricci 21st Century Roundtable on the History of Christianity in China." Includes Bibliographies (an unannotated listing); biographies of people who played a role in the history of Christianity in China, web links.

- Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity

- Timeline of Orthodoxy in China

- Asia Harvest: Map of the Distribution of Christians in China Map by Global Mapping International - retrieved February 9, 2012

- Tait Papers: <archival description of the papers of Ruth Tait>; National Library of Scotland. Mundus: gateway to missionary collections in the United Kingdom

- Young, George Armstrong: <archival description of the papers of George Armstrong Young>; Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World, University of Edinburgh. Mundus: gateway to missionary collections in the United Kingdom

- "Spotlight on China" Regional distribution of Christianity, Pew Research Religion and Public Life Project. See esp. Appendix C Methodology for China