Occupy Wall Street

| Occupy Wall Street | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Occupy movement | |

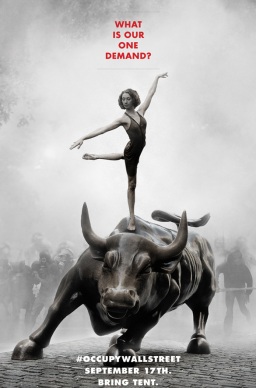

Adbusters poster promoting the start date of the occupation, September 17, 2011. | |

| Date | September 17, 2011 – ongoing (12 years, 8 months and 5 days) |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Wealth inequality, Corporate influence of government, Populism, (in support of) Social Democracy, inter alia. |

| Methods | |

| Status | Ongoing |

| Number | |

| Zuccotti Park

Other activity in NYC:

| |

Occupy Wall Street is the original protest that began the worldwide movement beginning September 17, 2011 in Zuccotti Park, located in New York City's Wall Street financial district, initiated by the Canadian activist group Adbusters. The protests are against social and economic inequality, high unemployment, greed, as well as corruption and the undue influence of corporations on government—particularly from the financial services sector. The protesters' slogan We are the 99% refers to the growing income and wealth inequality in the U.S. between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the population. The protests in New York City have sparked similar Occupy protests and movements around the world.

Overview

Origin

In a blog post from July 13, 2011, the Canadian-based Adbusters Media Foundation, best known for its advertisement-free, anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters, proposed a peaceful occupation of Wall Street to protest corporate influence on democracy, the absence of legal repercussions for those behind the recent global financial crisis, and a growing disparity in wealth.[5][6] They sought to combine the symbolic location of the 2011 protests in Tahrir Square with the consensus decision making of the 2011 Spanish protests.[7] Adbusters' senior editor, Micah White, said they had suggested the protest via their email list and it "was spontaneously taken up by all the people of the world.”[6] Adbusters' website said that from their "one simple demand, a presidential commission to separate money from politics," they would "start setting the agenda for a new America."[8] They promoted the protest with a poster featuring a dancer atop Wall Street's iconic Charging Bull statue.[9][10]

The internet group Anonymous encouraged its readers to take part in the protests, calling for protesters to "flood lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street for a few months."[11][12] Other groups began to join in the organization of the protest, including the U.S. Day of Rage[13] and the NYC General Assembly, which became the governing body of Occupy Wall Street.[14] The protest itself began on September 17; a Facebook page for the demonstrations began two days later on September 19 featuring a YouTube video of earlier events. By mid-October, Facebook listed 125 Occupy-related pages, and roughly one in every 500 hashtags used on Twitter—all over the world—was the movement's own #OWS.[15]

Adbusters' Kalle Lasn, when asked why it took three years after the implosion of Lehman Brothers for people to begin protesting, said that after the election of President Barack Obama there was a feeling among the young that he would pass laws to regulate the banking system and "take these financial fraudsters and bring them to justice." However, as time passed, "the feeling that he's a bit of a gutless wonder slowly crept in" and they lost their hope that his election would result in change.[16]

Zuccotti Park, the site of the occupation, was chosen because it was private property and police could not legally force protesters to leave without being requested to do so by the property owner.[17] At a press conference held on the same day as the protests began, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg explained, "people have a right to protest, and if they want to protest, we'll be happy to make sure they have locations to do it."[14] Writing for CNN, Sonia Katyal and Eduardo Peñalver said that "a straight line runs from the 1930s sit-down strikes in Flint, Michigan, to the 1960 lunch-counter sit-ins to the occupation of Alcatraz by Native American activists in 1969 to Occupy Wall Street. Occupations employ physical possession to communicate intense dissent, exhibited by a willingness to break the law and to suffer the -- occasionally violent -- consequences."[18]

More immediate prototypes for Occupy Wall Street are the British student protests of 2010, Greece and Spain's anti-austerity protests of the "indignados" (indignants), as well as the Middle East's Arab Spring protests. These antecedents have in common with Occupy Wall Street a reliance on social media and electronic messaging to circumvent the authorities, as well as the feeling that financial institutions, corporations, and the political elite have been malfeasant in their behavior toward youth and the middle class.[19][20] Occupy Wall Street, in turn, gave rise to the Occupy movement in the United States and around the world.[21][22][23]

The 99%

The phrase "The 99%" is a political slogan of "Occupy" protesters.[30] It was originally launched as a Tumblr blog page in late August 2011.[31][32] It refers to the vast concentration of wealth among the top 1% of income earners compared to the other 99 percent, and indicates that most people are paying the price for the mistakes of a tiny minority.[19][33] Paul Taylor, executive vice president of the Pew Research Center told NPR that the slogan is "arguably the most successful slogan since 'Hell no, we won't go,' going back to the Vietnam era." According to Taylor, majorities of Democrats, independents and Republicans see the income gap as a cause of friction in the United States.[34]

The top 1 percent of income earners have more than doubled their income over the last thirty years according to a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report.[35] The report was released just as concerns of the Occupy Wall Street movement were beginning to enter the national political debate.[36] According to the CBO, between 1979 and 2007 the incomes of the top 1% of Americans grew by an average of 275%. During the same time period, the 60% of Americans in the middle of the income scale saw their income rise by 40%. Since 1979 the average pre-tax income for the bottom 90% of households has decreased by $900, while that of the top 1% increased by over $700,000, as federal taxation became less progressive. From 1992-2007 the top 400 income earners in the U.S. saw their income increase 392% and their average tax rate reduced by 37%.[37] In 2009, the average income of the top 1% was $960,000 with a minimum income of $343,927.[38][39][40]

In 2007 the richest 1% of the American population owned 34.6% of the country's total wealth, and the next 19% owned 50.5%. Thus, the top 20% of Americans owned 85% of the country's wealth and the bottom 80% of the population owned 15%. Financial inequality (total net worth minus the value of one's home)[41] was greater than inequality in total wealth, with the top 1% of the population owning 42.7%, the next 19% of Americans owning 50.3%, and the bottom 80% owning 7%.[42] However, after the Great Recession which started in 2007, the share of total wealth owned by the top 1% of the population grew from 34.6% to 37.1%, and that owned by the top 20% of Americans grew from 85% to 87.7%. The Great Recession also caused a drop of 36.1% in median household wealth but a drop of only 11.1% for the top 1%, further widening the gap between the 1% and the 99%.[42][43][44] During the economic expansion between 2002 and 2007, the income of the top 1% grew 10 times faster than the income of the bottom 90%. In this period 66% of total income gains went to the 1%, who in 2007 had a larger share of total income than at any time since 1928.[24] This is in stark contrast with surveys of US populations that indicate an "ideal" distribution that is much more equal, and a widespread ignorance of the true income inequality and wealth inequality.[45]

Goals

Protesters targeted Wall Street because of the part it played in the economic crisis of 2008 which started the Great Recession. They say that Wall Street's risky lending practices of mortgage-backed securities which ultimately proved to be worthless caused the crisis, and that the government bailout breached a sense of propriety, and created a state of moral hazard in the banking industry. The protesters say that Wall Street recklessly and blatantly abused the credit default swap market, and that the instability of that market must have been known beforehand. They say that the guilty parties should be prosecuted.[23]

The protesters want, in part, more and better jobs, more equal distribution of income, bank reform, and a reduction of the influence of corporations on politics,[46][47] which they sometimes refer to as corporatocracy.[48][49] Adbusters co-founder Kalle Lasn has compared the protests to the Situationists and the Protests of 1968 movements.[23][50] and addresses critics saying that while no one person can speak for the movement, he believes that the goal of the protests is economic justice, specifically, a "transaction tax" on international financial speculation, the reinstatement of the Glass-Stegall Act and the revocation of corporate personhood.[7]

Some journalists have criticized the protests saying it is hard to discern a unified aim for the movement, while other commentators, such as Douglas Rushkoff, have said that although the movement is not in complete agreement on its message and goals, it does center on the problem that "investment bankers working on Wall Street [are] getting richer while things for most of the rest of us are getting tougher". According to Rushkoff, "... we are witnessing America's first true Internet-era movement, which -- unlike civil rights protests, labor marches, or even the Obama campaign -- does not take its cue from a charismatic leader, express itself in bumper-sticker-length goals and understand itself as having a particular endpoint".[46]

The General Assembly, the governing body of the OWS movement, has adopted a “Declaration of the Occupation of New York City,” which includes a list of grievances against corporations,[51] and to many protesters a general statement is enough. However, saying, "‘Power concedes nothing without a demand' " others within the movement have favored a fairly concrete set of national policy proposals.[52] One group has written an unofficial document, "The 99 Percent Declaration”, that calls for a national general assembly of representatives from all 435 congressional districts to gather on July 4, 2012, to assemble a list of grievances and solutions.[53][54][55] OWS protesters that prefer a looser, more localized set of goals have also written a document, the Liberty Square Blueprint,[56] a wiki page edited by some 250 occupiers and still undergoing changes. Written as a wiki the wording changes, however, an early version read: "Demands cannot reflect inevitable success. Demands imply condition, and we will never stop. Demands cannot reflect the time scale that we are working with."[53] The Guardian interviewed OWS and found three main demands: get the money out of politics; reinstate the Glass-Steagall act; and draft laws against the little-known loophole that currently allows members of Congress to pass legislation affecting Delaware-based corporations in which they themselves are investors.[57]

Demographics

Early on the protesters were mostly young, in part due to their pronounced use of social networks through which they promoted the protests.[58][59] As the protest grew, older protesters also became involved.[60] The average age of the protesters is 33, with people in their 20s balanced by people in their 40s.[61] Various religious faiths have been represented at the protest including Muslims, Jews, and Christians.[62][63] On October 10 the Associated Press reported that "there’s a diversity of age, gender and race" at the protest.[60] Some news organizations have compared the protest to a left-leaning version of the Tea Party protests.[64]

According to a survey of occupywallst.org website visitors[65] by the Baruch College School of Public Affairs published on October 19, of 1,619 web respondents, 1/3 were older than 35, half were employed full-time, 13% were unemployed and 13% earned over $75,000. When given the option of Democrat, Republican or Independent/Other 27.3% of the respondents called themselves Democrats, 2.4% called themselves Republicans, while the rest, 70%, called themselves independents.[66] A survey by Fordham University Department of Political Science confirmed and detailed this with political affiliations 25% Democrats, 2% Republican, 11% Socialist, 11% Green Party, 12% Other, and 39% who reported no party affiliation.[67] Ideologically the Fordham survey found 80% self-identifying as slightly to extremely liberal, 15% as moderate, and 6% as slightly to extremely conservative.

Racially, the majority of participants are White, with one study based on survey responses at OccupyWallStreet.org reporting 81.2% White, 7.6% Other, 6.8% Hispanic, 2.8% Asian, and 1.6% Black.[68][69]

New York City protests

The New York City General Assembly (NYCGA), held every evening at seven, is the main OWS decision-making body and provides much of the leadership and executive function for the protesters. At its meetings the various OWS committees discuss their thoughts and needs, and the meetings are open to the public for both attendance and speaking. The meetings are without formal leadership, although certain members routinely act as moderators. Meeting participants comment upon committee proposals using a process called a "stack", which is a queue of speakers that anyone can join. New York uses what is called a progressive stack, in which people from marginalized groups are sometimes allowed to speak before people from dominant groups, with facilitators, or stack-keepers, urging speakers to "step forward, or step back" based on which group they belong to, meaning that women and minorities may move to the front of the line, while white men must often wait for a turn to speak.[70][71][72] Volunteers take minutes of the meetings so that organizers who are not in attendance can be kept up-to-date.[73][74] In addition to the over 70 working groups[75] that perform much of the daily work and planning of Occupy Wall Street, the organizational structure also includes "spokes councils," at which every working group can participate.[76]

According to Fordham University communications professor Paul Levinson, Occupy Wall Street and similar movements symbolize another rise of direct democracy that has not actually been seen since ancient times.[77] Sociologist Heather Gautney, also from Fordham University, has said that while the organization calls itself leaderless, the protest in Zuccotti Park has discernible "organizers".[78] Even with the perception of a movement with no leaders, leaders have emerged. Ad hoc leaders discussed whether to leave. They plan for the occupation of other cities and neighborhoods, with an infrastructure to keep the movement beyond just the park. A facilitator of some of the movement's more contentious discussions, Nicole Carty, says “Usually when we think of leadership, we think of authority, but nobody has authority here,” - “People lead by example, stepping up when they need to and stepping back when they need to.”[79] According to TheStreet.com, some organizers have made more of a commitment and are more visible than others, with a core of about five main organizers being the most active.[80]

Critics of the General Assembly believe that consensus-based democracy cannot work in a group that is larger than a couple hundred people because it requires excessive amounts of monitoring in order to prevent free-riding, and works best with like-minded individuals. They also suggest that there is a higher chance of groupthink among consensus-based groups because there is pressure to conform in order to maintain consensus.[81]

Funding

Most of OWS funding comes from middle-class donors with incomes in the $50,000 to $100,000 range, and the median donation was $22.[61] According to finance group member Pete Dutro, OWS had accumulated over $600,000 and had $450,000 remaining as of November 21, 2011. Between October 1 2011 and January 4 2012 Occupy Wall Street collected a total of $706,855.91.[82] During the period that protesters were encamped in the park the funds were being used to purchase food and other necessities and to bail out fellow protesters. In the future members of the OWS finance committee say they will initiate a process to streamline the movement and re-evaluate their budget. They may eliminate or restructure some of the "working groups" they no longer need on a day-to-day basis. "We have some ideas but we want to hear ideas from the other working groups," said Dutro, "So we can put forward a proposal that would be fair and suit everybody's needs." Presently the movement continues to organize out of donated office space and give money to other "occupations." [83]

According to The Wall Street Journal, "A few weeks ago, the Alliance for Global Justice, a Washington-based nonprofit, agreed to sponsor Occupy Wall Street and lend it its tax-exempt status, so donors could write off contributions. That means the Alliance for Global Justice's board has final say on spending, though it says it's not involved in decisions and will only step in if the protesters want to spend money on something that might violate their tax-exempt status."[84][84][85] As of late October it was reported that the OWS Finance Committee works with a lawyer and an accountant to track finances; the group has a substantial amount of money deposited at the Amalgamated Bank nearby, after first making deposits at the Lower East Side People's Federal Credit Union.[86] In late October the General Assembly of Occupy Wall Street registered for tax exempt status as a 501(c)(3)[87] Occupy Wall Street accepts tax-deductible donations, primarily through the movement's website.[83]

Zuccotti Park occupation

Prior to being closed to overnight use, somewhere between 100 and 200 people slept in Zuccotti Park. Initially tents were not allowed and protesters slept in sleeping bags or under blankets.[88] Meal service started at a total cost of about $1,000 per day; while some visitors ate at nearby restaurants[89] according to the New York Post local vendors fared badly[90] and many businesses surrounding the park were adversely affected.[91] Other Contribution boxes collected about $5,000 a day, and supplies came in from around the country.[89] Eric Smith, a local chef who was laid off at the Sheraton in Midtown, said that he was running a five-star restaurant in the park.[92] In late-October kitchen volunteers complained about working 18 hour days to feed people who were not part of the movement and served only brown rice, simple sandwiches, and potato chips for three days.[93]

The protesters constructed a greywater treatment system to recycle dishwater contaminants. The filtered water was used for the park's plants and flowers. Many protesters used the bathrooms of nearby business establishments. Some supporters donated use of their bathrooms for showers and the sanitary needs of protesters.[94]

New York City requires a permit to use "amplified sound," including electric bullhorns. Since Occupy Wall Street does not have a permit, the protesters have created the "human microphone" in which a speaker pauses while the nearby members of the audience repeat the phrase in unison. The effect has been called "comic or exhilarating—often all at once." Some feel this has provided a further unifying effect for the crowd.[95][96]

During the weeks that overnight use of the park was allowed, a separate area was set aside for an information area which contained laptop computers and several wireless routers.[97][98] The items were powered with gas generators until the New York Fire Department removed them on October 28, saying they were a fire hazard.[99] Protesters then used bicycles rigged with an electricity-generating apparatus to charge batteries to power the protesters' laptops and other electronics.[100] According to the Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, the media team, while unofficial, runs websites like Occupytogether.org, video livestream, a "steady flow of updates on Twitter, and Tumblr" as well as Skype sessions with other demonstrators.[101]

In October a makeshift tent was erected, formally calling itself The People's Library, and began offering free wi-fi internet to protesters and containing over 5,000 books. The library operated 24/7 and used an honor system to manage returns. It offered weekly poetry readings on Friday nights, provided a reference serviced frequently staffed by professional librarians, and procured materials available through the interlibrary loan system.[102] However, the library was removed on November 15 when the park was closed to overnight use and it was reported that many of the books were destroyed. The library's cataloging system is accessible online at LibraryThing, which donated a free lifetime membership.

On October 6, Brookfield Office Properties, which owns Zuccotti Park, issued a statement that "Sanitation is a growing concern... Normally the park is cleaned and inspected every weeknight[, but] because the protesters refuse to cooperate ... the park has not been cleaned since Friday, September 16 and as a result, sanitary conditions have reached unacceptable levels."[103][104]

On October 13, New York City's mayor Bloomberg and Brookfield announced that the park must be vacated for cleaning the following morning at 7 am.[105] However, protesters vowed to "defend the occupation" after police said they wouldn’t allow them to return with sleeping bags and other gear following the cleaning, under rules set by the private park’s owner—and many protesters spent the night sweeping and mopping the park.[106][107] The next morning, the property owner postponed its cleaning effort.[106] Having prepared for a confrontation with the authorities to prevent the cleaning effort from proceeding, some protesters clashed with police in riot gear outside City Hall after it was canceled.[105]

Shortly after midnight on November 15, 2011, the New York Police Department gave protesters notice from the park's owner (Brookfield Office Properties) to leave Zuccotti Park due to its purportedly unsanitary and hazardous conditions. The notice stated that they could return without sleeping bags, tarps or tents.[108][109] About an hour later, police in riot gear began removing protesters from the park, arresting some 200 people in the process, including a number of journalists. While the police raid was in progress, the Occupy Wall Street Media Team issued an official response under the heading, "You can't evict an idea whose time has come."[110]

On December 31, 2011, Protesters started to re-occupy the park. Police were first called in when a mother and her two children had a tent set up for the children to play in. The police claimed that the tent violated the law of no camping in the park. The tent was eventually given up by protesters and protesters were allowed in the park around 8 p.m.[111] Later on, protesters started to push police barricades into the streets.

Police quickly put the barricades back up. Occupiers then started to take down barricades from all sides of the park and stored them in a pile in the middle of Zuccotti Park.[112] Police called in re-enforcements while at the same time more activist entered the park. Police tried to enter the park, but were push back by protesters. There were reports of pepper-spray being used by the police. About 12:40 a.m. after the group celebrated New Years in the park, They exited the park and marched down Broadway. Police, in riot gear, started to clear out the park around 1:30 a.m. According to New York Times, the park was cleared out by police by 2:30 a.m. Sixty-eight people were arrested in connection with the event, which was over within several hours.[113]

Since the closure of the Zuccotti Park encampment, some former campers have been allowed to sleep in local churches, but how much longer they will be welcomed is in question and even former park Occupiers debate whether or not they can continue to provide funds and meals for homeless protesters. Since the police raid, New York protesters have been divided in their opinion as to the importance of the occupation of a space with some believing that actual encampment is unnecessary, and even a burden.[114]

Reaction

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Among the general public, opinions of OWS have varied over time, and there are contradictions between the data collected by various polling agencies. Many prominent politicians, academics and celebrities of varying degree have weighed in with their reaction and responses. Mass media of all genre as well as labor unions, the banking industry and business people have given statements and given both financial as well as moral support.

Crime

On October 11, it was reported that OWS protesters staying in Zuccotti Park were dealing with a worsening security problem with reports of multiple incidents of assault, drug dealing and use, and sexual assault.[115] A Crown Heights man was charged with sexually assaulting a protester at the park raising the level of public discussion of lawlessness at the demonstrations. Protesters used de-escalation techniques such as talking down and body-blocking of people throwing punches. In more tense situations, protesters encircled troublemakers and usherd them out. But many times, those kicked out or arrested returned.[116] But most protesters said that the most serious concern was the risk of assault, especially for women and at night. Demonstrators complained of thefts of assorted items such as cell phones and laptops; thieves also stole $2500 of donations that were stored in a makeshift kitchen.[117] On October 10, a "methadone-addled man freeloading off the Wall Street protest" was arrested for groping a woman.[115] On Nov 10, 2011, a man was arrested at OWS for breaking an EMT's leg.[118]

Police Commissioner Paul Browne complained that protesters delayed reporting crime. He stated that it's OWS protocol not to report such incidents to the police until there were three complaints against the same individual.[119] The protesters denied a "three strikes policy", and one protester told the New York Daily News that he had heard police respond to a complaint by saying, "You need to deal with that yourselves".[120]

- "A lot of the folks that are involved in the security operations at the park have been saying that -- when they encounter, you know, sort of transient, homeless type of people there in the park -- they are hearing reports that the police have been encouraging them to head down to Zuccotti, to "Take it to Zuccotti." It's very upsetting. Particularly, when you consider that some of the people that are arriving to the park have severe psychiatric problems or drug-addiction problems." Ryan Devereaux, reporter for Democracy Now!.[121][122]

After several weeks of occupation, Occupy Wall Street protesters had made enough allegations of sexual assault and gropings that women-only sleeping tents were set up.[123] One man was arrested for a sexual assault that occurred in Zuccotti Park on October 8. At the time of the incident, he had numerous warrants for his arrests. A kitchen helper was charged with an October 24 sexual assault of an 18-year-old fellow protester. Prosecutors believe he is responsible for an assault of another 18-year-old woman.[124][125][126] Occupy Wall Street organizers released a statement regarding the sexual assaults stating, "As individuals and as a community, we have the responsibility and the opportunity to create an alternative to this culture of violence, We are working for an OWS and a world in which survivors are respected and supported unconditionally... We are redoubling our efforts to raise awareness about sexual violence. This includes taking preventative measures such as encouraging healthy relationship dynamics and consent practices that can help to limit harm.”[127]

Chronology

September

On September 17, 1,000 protesters marched through the streets, with an estimated 100 to 200 staying overnight in cardboard boxes. By September 19, seven people had been arrested.[128][129] At least 80 arrests were made on September 24,[130] after protesters started marching uptown and forcing the closure of several streets.[131][132] Most of the 80 arrests were for blocking traffic, though some were also charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. Police officers used a technique called kettling which involves using orange nets to isolate protesters into smaller groups.[131][132] Videos which showed several penned-in female demonstrators being hit with pepper spray by a police official were widely disseminated, sparking controversy.[133] That police official was identified as Deputy Inspector Anthony Bologna. Initially Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly and a representative for Bologna defended his actions, while decrying the disclosure of his personal information by the group "Anonymous".[133][134] After growing public furor, Kelly announced that Internal Affairs and the Civilian Complaint Review Board were opening investigations,[133] again criticizing Anonymous for "[trying] to intimidate, putting the names of children, where children go to school," and adding that this tactic was "totally inappropriate, despicable."[133] Meanwhile, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. started his own inquiry.[134]

Public attention to the pepper-sprayings resulted in a spike of news media coverage, a pattern that was to be repeated in the coming weeks following confrontations with police.[135] Clyde Haberman, writing in The New York Times, said that "If the Occupy Wall Street protesters ever choose to recognize a person who gave their cause its biggest boost, they may want to pay tribute to Anthony Bologna," calling the event "vital" for the still nascent movement.[136][137] "After Ron Kuby, an attorney for one of the protesters, demanded Mr. Bologna’s arrest, [Bologna] was instead docked 10 vacation days and given a [...] reassignment to Staten Island, where he lives," according to an account by blogger Daniel Edward Rosen.[138]

On October 1, 2011, protesters set out to march across the Brooklyn Bridge. The New York Times reported that more than 700 arrests were made.[139] The police used ten buses to carry protesters off the bridge. By October 2, all but 20 of the arrestees had been released with citations for disorderly conduct and a criminal court summons.[140] On October 4, a group of protesters who were arrested on the bridge filed a lawsuit against the city, alleging that officers had violated their constitutional rights by luring them into a trap and then arresting them; Mayor Bloomberg, commenting previously on the incident, had said that "[t]he police did exactly what they were supposed to do."[141]

On October 5, thousands of union workers joined protesters marching through the Financial District. The march was mostly peaceful until after nightfall, when scuffles erupted. About 200 protesters tried to storm barricades blocking them from Wall Street and the Stock Exchange. Police responded with pepper spray and penned the protesters in with orange netting.[142][143]

October

On October 15, tens of thousands of demonstrators staged rallies in 900 cities around the world, including Auckland, Sydney, Hong Kong, Taipei, Tokyo, São Paulo, Paris, Madrid, Berlin, Hamburg, Leipzig, and many other cities.[144] In Frankfurt, 5,000 people protested at the European Central Bank and in Zurich, Switzerland's financial hub, protesters carried banners reading "We won't bail you out yet again" and "We are the 99 percent." Protests were largely peaceful, however a protest in Rome that drew thousands turned violent when "a few thousand thugs from all over Italy, and possibly from all over Europe" caused extensive damage.[145] Thousands of Occupy Wall Street protesters gathered in Times Square in New York City and rallied for several hours.[146][147] Several hundred protesters were arrested across the U.S., mostly for refusing to obey police orders to leave public areas. In Chicago there were 175 arrests, about 100 arrests in Arizona (53 in Tucson, 46 in Phoenix), and more than 70 in New York City, including at least 40 in Times Square.[148] Multiple arrests were reported in Chicago, and about 150 people camped out by city hall in Minneapolis.[149]

In the early morning hours of October 25, police cleared and closed an Occupy Oakland encampment at Frank Ogawa Plaza in Oakland, California.[150][151] The raid on the encampment was described as "violent and chaotic at times," and resulted in over 102 arrests and several injuries to protesters. The city of Oakland contracted the use of over 12 other regional police departments to aid in the clearing of the encampment. An Iraqi war veteran, Scott Olsen, was allegedly hit in the head with a teargas canister and suffered a skull fracture. His condition was later upgraded from critical to fair.[152] The next night, approximately 1,000 protesters reconvened in the plaza and during General Assembly voted to hold a general strike on November 2, 2011 which would include shutting down the Port of Oakland. They went on to hold marches late into the night.[153]

November

On November 2, protesters in Oakland, California shut down the Port of Oakland, the fifth busiest port in the nation. Police estimated that about 3,000 demonstrators were gathered at the port and 4,500 had marched across the city; a spokesman for the protest movement, who gave only his first name, told the BBC that he had heard people say that there were as many as 20,000 or 30,000 demonstrators, but added, "It's impossible to tell."[154]

After midnight on November 15, police delivered notices that protesters had to temporarily vacate the park to allow cleaning/sanitation crews access.[155] According to the police notice, protesters would have been allowed back in after the cleaning, but without tents, tarps, or sleeping bags. Police moved in around 1:00 AM on November 15 and arrested about 200 people, some of whom attempted to stop the entry of cleaning crews. Among those arrested were journalists representing the Agence France-Presse,[156] Associated Press,[157] Daily News,[158] DNAInfo,[159] NPR,[160] Television New Zealand,[161] The New York Times,[162] and Vanity Fair,[163] as well as New York City Council member Ydanis Rodríguez.[164] An NBC reporter's press pass was also confiscated.[165]

While the police cleared the park, credentialed members of the media were kept a block away, preventing them from documenting the event.[166][167] Police helicopters prevented NBC and CBS news helicopters from filming the clearing of the park.[168] Many journalists complained of being treated roughly or violently by the police.[169][170][171][172] The Society of Professional Journalists, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Reporters Without Borders and the New York Civil Liberties Union expressed concerns and criticisms regarding the situation.[159][173][174][175] The OAS Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression issued a statement saying that the "disproportionate restrictions on access to the scene of the events, the arrests, and the criminal charges resulting from the performance of professional duties by reporters violate the right to freedom of expression."[176]

On November 21, the New York Daily News, the New York Post, the Associated Press, Dow Jones, NBC Universal and WNBC-TV joined in a letter written by New York Times General Council George Freeman criticizing the New York Police Department's handling of the media during the raid.

[177]

Half an hour into the police removal, the Occupy Wall Street Media Team put out an official statement under the heading, "You can't evict an idea whose time has come." It went on to say, "Some politicians may physically remove us from public spaces — our spaces — and, physically, they may succeed. But we are engaged in a battle over ideas."[110]

The tents and personal effects of the protesters, and the five thousand books of The People's Library[178] were put in dump trucks by the police and removed.[179] On the November 15 edition of The Rachel Maddow Show, footage of the raid was shown with the following commentary:

- "New York City police officers dressed in riot gear, handed out a written notice to the protesters telling them where their personal articles from the encampment could be retrieved, which sounds lovely until you saw what they were doing to the protesters` personal belongings. There were reports that police use knives to cut up the sturdy military-grade tents that were the best hope of surviving winter down there. You can see police here cutting down the protesters` tent poles with hand-held saws, with sawsalls."[180][181]

Computers retrieved after the raid were found to be smashed.[182][183][184][185][186]

After the removal, New York City officials ordered police to keep the entire park closed and to prevent any protesters from returning, pending the outcome of a court hearing on whether and in what circumstances the protesters could return; a judge issued a temporary restraining order that protesters could return to the park with their tents, which Washington Post opinion writer James Downie accused Mayor Bloomberg of ignoring.[172][187] A judge in the late afternoon ruled that the temporary order should not be extended, saying that the First Amendment did not give protesters the right to fill the park with "tents, structures, generators, and other installations to the exclusion of the owner's reasonable rights and duties to maintain Zuccotti Park."[109][188]

On November 17, journalists representing the Independent Reader, IMC and In These Times were arrested.[189][190] Two reporters for the Daily Caller and a reporter for RT were reportedly struck with police batons.[190][191]

December

On December 6, Occupy Our Homes, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, embarked on a "national day of action" to protest the mistreatment of homeowners by big banks, who they say made billions of dollars off of the housing bubble by offering predatory loans and indulging in practices that took advantage of consumers. In more than two dozen cities across the nation the movement took on the housing crisis by re-occupying foreclosed homes, disrupting bank auctions and blocking evictions.[192] In a special for CNN, Sonia Katyal and Eduardo Peñalver said that the movement's turn toward foreclosed housing is important because it forms an obvious connection between the park occupation and the occupation of foreclosed homes.[18]

On December 14, another OWS offshoot, Occupy DOE (Department of Education), joined with teachers and parents to protest at a school board meeting in the Queens district of New York City. The group claims that the Panel on Educational Policy (PEP), largely appointed by Mayor Bloomberg, is an illegitimate, undemocratic, "parody of a school board". The PEP was scheduled to vote on a plan to open two new charter schools in Brooklyn run by Success network, an organization run by a former city councilwoman with close ties to the mayor and his administration. Almost everyone on the Success board has been involved with the hedge fund or private equity industry. The perception that "the one percent" could open schools in Brooklyn neighborhoods, despite intense opposition by the public and many elected officials, has provoked intense anger.[193]

On December 20, computer hackers from a loose online coalition called Anonymous exposed the personal information of police officers who have evicted OWS protesters.

January 2012

On January 3, 2012, approximately 200 Occupy protesters performed a flash mob at the main concourse of New York's Grand Central Terminal, in protest against President Obama's signing into law of the National Defense Authorization Act that the protesters and many independent commentators [194][195] perceived as detrimental to civil liberties.[196] It was reported that three people were arrested during the flash mob, and a spokesperson for New York's Metro Transportation Authority characterized the event by stating, "It was a peaceful but noisy protest."[196]

See also

|

Occupy articles Other U.S. protests

International |

Related articles

|

References

- ^ "Hundreds of Occupy Wall Street protesters arrested". BBC News. October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "700 Arrested After Wall Street Protest on N.Y.'s Brooklyn Bridge". Fox News Channel. October 1, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: protests and reaction Thursday 6 October". Guardian. London. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ “Wall Street protests span continents, arrests climb“, Crain's New York Business, October 17, 2011.

- ^ "From a single hashtag, a protest circled the world". Brisbanetimes.com.au. October 19, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Fleming, Andrew (September 27, 2011). "Adbusters sparks Wall Street protest Vancouver-based activists behind street actions in the U.S". The Vancouver Courier. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ a b "Sira Lazar "Occupy Wall Street: Interview With Micah White From Adbusters", Huffington Post, October 7, 2011, at 3:40 in interview". Huffingtonpost.com. October 7, 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ Adbusters, Adbusters, July 13, 2011; accessed September 30, 2011

- ^ Beeston, Laura (October 11, 2011). "The Ballerina and the Bull: Adbusters' Micah White on 'The Last Great Social Movement'". The Link. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Schneider, Nathan (September 29, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: FAQ". The Nation. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Saba, Michael (September 17, 2011). "Twitter #occupywallstreet movement aims to mimic Iran". CNN tech. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ Adbusters (August 23, 2011). "Anonymous Joins #OCCUPYWALLSTREET "Wall Street, Expect Us!" says video communique". Adbusters. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ "Assange can still Occupy centre stage". Smh.com.au. October 29, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "'Occupy Wall Street' to Turn Manhattan into 'Tahrir Square'". IBTimes New York. September 17, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "From a single hashtag, a protest circled the world". Brisbanetimes.com.au. October 19, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Tyee – Adbusters' Kalle Lasn Talks About OccupyWallStreet". Thetyee.ca. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Batchelor, Laura (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street lands on private property". CNNMoney. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Many of the Occupy Wall Street protesters might not realize it, but they got really lucky when they elected to gather at Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan

- ^ a b Occupy's new tactic has a powerful past By Sonia K. Katyal and Eduardo M. Peñalver, Special to CNN December 16, 2011

- ^ a b Apps, Peter (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street action part of global Arab Spring?". Reuters. Retrieved November 24, 2011. "What they all share in common is a feeling that the youth and middle class are paying a high price for mismanagement and malfeasance by an out-of-touch corporate, financial and political elite...they took on slogans from U.S. protesters who describe themselves as the "99 percent" paying the price for mistakes by a tiny minority."

- ^ Tahrir Square protesters send message of solidarity to Occupy Wall Street by Jack Shenker and Adam Gabbatt The Guardian, Tuesday 25 October 2011 "Much of the tactics, rhetoric and imagery deployed by protesters has clearly been inspired by this year's political upheavals in the Middle East..."

- ^ In the City and Wall Street, protest has occupied the mainstream By Polly Toynbee in The Guardian, Monday 17 October 2011 "From Santiago to Tokyo, Ottawa, Sarajevo and Berlin, spontaneous groups have been inspired by Occupy Wall Street."

- ^ Occupy Wall Street: A protest timeline "A relatively small gathering of young anarchists and aging hippies in lower Manhattan has spawned a national movement. What happened?"

- ^ a b c Top 5 targets of Occupy Wall Street The Christian Science Monitor by Maud Dillingham

- ^ a b "Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top. Recent Gains of Bottom 90 Percent Wiped Out." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ “By the Numbers.” Demos.org. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ Alessi, Christopher (October). "Occupy Wall Street's Global Echo". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The Occupy Wall Street protests that began in New York City a month ago gained worldwide momentum over the weekend, as hundreds of thousands of demonstrators in nine hundred cities protested corporate greed and wealth inequality.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jones, Clarence (October 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street and the King Memorial Ceremonies". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The reality is that 'Occupy Wall Street' is raising the consciousness of the country on the fundamental issues of poverty, income inequality, economic justice, and the Obama administration's apparent double standard in dealing with Wall Street and the urgent problems of Main Street: unemployment, housing foreclosures, no bank credit to small business in spite of nearly three trillion of cash reserves made possible by taxpayers funding of TARP.

- ^ Chrystia Freeland (October 14, 2011). "Wall Street protesters need to find their 'sound bite'". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Michael Hiltzik (October 12, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street shifts from protest to policy phase". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Prescott protesters call for more infrastructure investment". Western News&Info, Inc. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ ""We Are the 99 Percent" Creators Revealed". Mother Jones and the Foundation for National Progress. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The World's 99 Percent". FOREIGN POLICY, PUBLISHED BY THE SLATE GROUP. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Wall Street protests spread". CBS News. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The Income Gap: Unfair, Or Are We Just Jealous? by Scott Horsley National Public Radia January 14, 2012

- ^ Pear, Robert (October 25, 2011). "Top Earners Doubled Share of Nation's Income, Study Finds". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "CBO: Incomes of top earners grow at a pace far faster than everyone else's". The Washington Post. October 26, 2011. Retrieved 11-17-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ It's the Inequality, Stupid By Dave Gilson and Carolyn Perot in Mother Jones, March/April 2011 Issue

- ^ Who are the 1 percent?, CNN, October 29, 2011

- ^ "Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ Top Earners Doubled Share of Nation’s Income, Study Finds New York Times By Robert Pear, October 25, 2011

- ^ "Financial wealth" is defined by economists as "total net worth minus the value of one's home," including investments and other liquid assets.

- ^ a b Occupy Wall Street And The Rhetoric of Equality Forbes November 1, 2011 by Deborah L. Jacobs

- ^ Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze—an Update to 2007 by Edward N. Wolff, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2010

- ^ Wealth, Income, and Power by G. William Domhoff of the UC-Santa Barbara Sociology Department

- ^ Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. Building a Better America—One Wealth Quintile at a Time Perspectives on Psychological Science January 2011 6: 9-12

- ^ a b Think Occupy Wall St. is a phase? You don't get it By Douglas Rushkoff, Special to CNN October 5, 2011 "...there are a wide array of complaints, demands, and goals from the Wall Street protesters: the collapsing environment, labor standards, housing policy, government corruption, World Bank lending practices, unemployment, increasing wealth disparity and so on...they believe they are symptoms of the same core problem. Are they ready to articulate exactly what that problem is and how to address it? No, not yet. But neither are Congress or the president..."

- ^ Occupy Wall Street: It’s Not a Hippie Thing By Roger Lowenstein, Bloomberg Businessweek October 27, 2011

- ^ Anita Simons (October 24, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street will go down in history". Maui News. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

... we all have different personal objectives, such as ending corporatocracy, ...

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Roman Haluszka (Nov 12 2011). "Understanding Occupy's message". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ben Piven (October 7, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: All day, all week". Aljazeera. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Forum Post: First OFFICIAL Release from OCCUPY WALL STREET". OccupyWallSt.org. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ New York Times

- ^ a b "Occupy Protesters' One Demand: A New New Deal—Well, Maybe". Mother Jones. October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Walsh, Joan (October 20, 2011). "Do we know what OWS wants yet?". Salon.com. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ "The99PercentDeclaration". Sites.google.com. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Liberty Square Blueprint — The Commons". Freenetworkmovement.org. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Naomi Wolf. The shocking truth about the crackdown on Occupy guardian.co.uk, Friday 25 November 2011 12.25 EST

- ^ Kleinfield, N.R.; Buckley, Cara (September 30, 2011). "Wall Street Occupiers, Protesting Till Whenever". New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Protesters 'Occupy Wall Street' to Rally Against Corporate America, Ray Downs, Christian Post, September 18, 2011

- ^ a b Protesters Want World to Know They’re Just Like Us, Jocelyn Noveck, Associated Press via the Long Island Press, October 10, 2011

- ^ a b Who is Occupy Wall Street? After six weeks, a profile finally emerges. The Christian Science Monitor By Gloria Goodale, November 1, 2011

- ^ "Religion claims its place in Occupy Wall Street". Boston University. 2011.

Inside, a Buddha statue sits near a picture of Jesus, while a hand-lettered sign in the corner points toward Mecca.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|=ignored (help) - ^ Vitchers, Tracey (September 26, 2011). "Occupying—Not Rioting—Wall Street". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ "As Occupy Wall Street explodes, the movement is being pegged as a left-wing Tea Party John Avlon on the key differences between the protests—and why they both miss the mark" "Tea Party for the Left?", The Daily Beast, posted October 10, 2011, accessed October 11, 2011

- ^ [1] By Occupywallst, OccupyWallSt.org 19 OCT 2011

- ^ The Demographics Of Occupy Wall Street BY Sean Captain, Fast Company, Oct 19, 2011

- ^ [2] By Professor Costas Panagopoulos, Fordham University, October 2011

- ^ "Infographic: Who Is Occupy Wall Street?". FastCompany.com. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ Parker, Kathleen (November 26, 2011). "Why African Americans aren't embracing Occupy Wall Street". Washington Post. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ Seltzer, Sarah (October 29, 2011). "Where Are the Women at Occupy Wall Street?". The Nation. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Penny, Laura (October 16, 2011). "Protest By Consensus". New Statesman. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Hinkle, A. Barton (November 4, 2011). "OWS protesters have strange ideas about fairness". Richmond Times Dispatch. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Occupy Wall Street Expands, Tensions Mount Over Structure International Business Times by Jeremy B. White, October 25, 2011

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street’s Media Team, Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, October 5, 2011

- ^ New York City General Assembly website, last visited 20 Nov. 2011

- ^ The New York Observer, 8 Nov. 2011, Occupy Wall Street Moves Indoors With Spokes Council

- ^ "Does 'Occupy Wall Street' have leaders? Does it need any?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Astor, Maggie (October 4, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street Protests: A Fordham University Professor Analyzes the Movement". International Business Times. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Fordham University Sociologist Heather Gautney in an interview with the International Business Times 'the movement doesn't have leaders, but it certainly has organizers, and there are certainly people providing a human structure to this thing. There might not be these kinds of public leaders, but there are people running it, and I think that's inevitable.'

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street takes a new direction". Crain Communications Inc. Retrieved 11-13-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "5 Occupy Wall Street Leaders (Update 1)". TheStreet, Inc. Retrieved 11-14-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Leaderless, consensus-based participatory democracy and its discontents". The Economist. October 19, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ^ Giove, Candice (2012-1-8). "OWS has money to burn". nypost.com.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Burruss, Logan (November 21, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street has money to burn". CNN.com. Retrieved 11-21-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Protest's Money Problem. Occupy Wall Street May Have to Appoint Leaders to Deal With Its Donations" by Andrew Grossman. The Wall Street Journal. October 27, 2011

- ^ Grossman, Andrew (October 27, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's Money Problem — WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Frank, Robert (October 22, 2011). "Goldman Sachs Sends Its Regrets to This Awkward Dinner Invitation". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ "Money Donated To Occupy Wall Street Brings Much Needed Supplies And Tension" by Lila Shapiro. The Huffington Post. October 24, 2011.

- ^ "Somewhere between 100 and 200 people sleep in Zuccotti Park...." "Many occupiers were still in their sleeping bags at 9 or 10 am" Wall Street functions like a small city, Associated Press, October 7, 2011

- ^ a b The Occupy Economy, by Anne Kadet, Wall Street Journal, October 15, 2011

- ^ Oloffson, Kristi (October 12, 2011). "Food Vendors Find Few Customers During Protest". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ GIOVE, CANDICE (November 13, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street costs local businesses $479,400!". New York Post. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Protest mob is enjoying rich diet By REBECCA ROSENBERG, New York Post, October 19, 2011

- ^ Occupy Wall Street kitchen staff protesting fixing food for freeloaders By Selim Algar and Bob Fredricks, New York Post, October 27, 2011

- ^ Kadet, Anne (October 15, 2011). "The Occupy Economy". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Richard Kim on October 3, 2011 – 7:19 pm ET (October 3, 2011). "We Are All Human Microphones Now". The Nation. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "A general assembly of anyone who wants to attend meets twice daily. Because it's hard to be heard above the din of lower Manhattan and because the city is not allowing bullhorns or microphones, the protesters have devised a system of hand symbols. Fingers downward means you disagree. Arms crossed means you strongly disagree. Announcements are made via the "people's mic... you say it and the people immediately around you repeat it and pass the word along. "Wall Street functions like a small city, Associated Press, October 7, 2011

- ^ "Behind the sign marked “info” sat computers, , generators, wireless routers, and lots of electrical cords. This is the media center, where the protesters group and distribute their messages. Those who count themselves among the media team for Occupy Wall Street are self appointed; the same goes with all teams within this community." ""I later learned that power comes from a gas-powered generator which runs, among other things, multiple 4G wireless Internet hotspots that provide Internet access to the scrappy collection of laptops." "Occupy Wall Street’s Media Team, Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, October 5, 2011

- ^ The Technology Propelling #OccupyWallStreet , the Daily Beast , October 6, 2011

- ^ New York Authorities Remove Fuel, Generators From Occupy Wall Street Site, Esmé E. Deprez and Charles Mead, Bloomberg News, Oct 28, 2011; accessed November 2, 2011

- ^ With Generators Gone, Wall Street Protesters Try Bicycle Power, Colin Moynihan, New York Times, October 30, 2011; accessed November 2, 2011

- ^ "as the protest has grown, the media team has been busy coordinating, notably through the “unofficial,” Occupytogether.org. It’s a hub for all Occupy-inspired happenings and updates, a key part of the internal communications network for the Occupy demonstrations. While sitting in the media tent I saw several Skype sessions with other demonstrators. At one point a bunch of people gathered around a computer shouting, “Hey Scotland!” Members of the media team also maintain a livestream, and keep a steady flow of updates on Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr." "Occupy Wall Street’s Media Team, Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, October 5, 2011

- ^ "Voices from Zuccotti: Steve Syrek, 33". The New York Daily News. YouTube. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

I've even got one guy who wants to help us procure any materials we want from the interlibrary loan system, which means we are a legitimate, fully functioning research library. Someone could come here and request an article of any kind and we could theoretically get it for free and give it to them.

- ^ Kelly: Protesters To Be ‘Met With Force’ If They Target Officers, CBS News, October 6, 2011

- ^ Grossman, Andrew (September 26, 2011). "Protest Has Unlikely Host". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Allison Kilkenny on October 14, 2011 – 8:46 am ET. "Occupy Wall Street Protesters Win Showdown With Bloomberg". The Nation. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Cleanup Canceled", BusinessWeek, 2011-10-14.

- ^ Deprez, Esmé E., Joel Stonington and Chris Dolmetsch, "Occupy Wall Street Park Cleaning Postponed", Bloomberg, Oct 14, 2011 11:37 AM EDT.

- ^ Walker, Jade (November 15, 2011). "Zuccotti Park Eviction: NYPD Orders Occupy Wall Street Protesters To Temporarily Evacuate Park [LATEST UPDATES]". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ a b CNN Wire Staff (November 15, 2011). "New York court upholds eviction of "Occupy" protesters". www.cnn.com. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

A New York Supreme Court has ruled not to extend a temporary restraining order that prevented the eviction of "Occupy" protesters who were encamped at Zuccotti Park, considered a home-base for demonstrators. Police in riot gear cleared out the protesters early Tuesday morning, a move that attorneys for the loosely defined group say was unlawful. But Justice Michael Stallman later ruled in favor of New York city officials and Brookfield properties, owners and developers of the privately-owned park in Lower Manhattan. The order does not prevent protesters from gathering in the park, but says their First Amendment rights not do include remaining there, "along with their tents, structures, generators, and other installations to the exclusion of the owner's reasonable rights and duties to maintain Zuccotti Park."

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help); line feed character in|quote=at position 208 (help) Cite error: The named reference "RestrainingOrderVacated" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "You can't evict an idea whose time has come."- official statement of Occupy Wall Street Media Team, posted November 15, 2011, 1:36 a.m. EST

- ^ "Before Midnight, Occupy Wall Street Activists Retake Zuccotti Park". Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Protesters Occupy New Year in Zuccotti Park". Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "OWS Clash With Police At Zuccotti Park". Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "After Occupy Wall Street Encampment Ends, NYC Protesters Become Nomads". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ a b Freund, Helen; Cartwright, Lachlan; Saul, Josh (October 11, 2011). "'Occupy' crasher busted in grope". www.nypost.com.

- ^ Buckley, Cara; Flegenheimer, Matt (November 8, 2011). "At Scene of Wall St. Protest, Rising Concerns About Crime". New York Times. Retrieved 11-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Celona, Larry (October 18, 2011). "Thieves preying on fellow protesters". www.nypost.com.

- ^ Siegal, Ida. "Man Arrested for Breaking EMT's Leg at Occupy Wall Street". NBC New York. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg: Crime at Occupy Wall Street goes unreported". Free Daily News Group Inc. Retrieved 11-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Occupy Wall Street protesters at odds with Mayor Bloomberg, NYPD over crime in Zuccotti Park". New York: NYDailyNews.com. Retrieved 11-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Countdown with Keith Olbermann transcript October 31, 2011

- ^ New York Daily News, 30 Oct. 2011, At Occupy Wall Street Central, a Rift Is Growing between East and West Sides of the Plaza: The Wall Street Protesters Determined to "Occupy Everything" Now Find Themselves, in a Sense, Occupied

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street Erects Women-Only Tent After Reports Of Sexual Assaults". The Gothamist News. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Schram, Jamie (November 3, 2011). "Protester busted in tent grope, suspected in rape of another demonstrator". NY POST. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Man Arrested For Groping Protester Also Eyed In Zuccotti Park Rape Case". WPIX. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Dejohn, Irving; Kemp, Joe. "Arrest made in Occupy Wall St. sex attack; Suspect eyed in another Zuccotti gropingCase". New York: NY Daily News. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Protests Plagued by Reports of Sex Attacks, Violent Crime". NY Daily News. November 9, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Marcinek, Laura (September 19, 2011). "NYPD Arrest Seven Wall Street Protesters". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Marcinek, Laura (September 19, 2011). "Wall Street Areas Blocked as Police Arrest Seven in Protest". Businessweek. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Candice. "Occupy Wall Street Movement Reports 80 Arrested Today in Protests". abc. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Police Arrest 80 During 'Occupy Wall Street' Protest". Fox New.com. September 24, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Moynihan, Colin (September 24, 2011). "80 Arrested as Financial District Protest Moves North". The New York Times. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Christina Boyle and John Doyle. "Pepper-spray videos spark furor as NYPD launches probe of Wall Street protest incidents". The Daily News. New York. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Al Baker and Joseph Goldstein (September 28, 2011). "Officer's Pepper-Spraying of Protesters Is Under Investigation". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Nate Silver (October 7, 2011). "Police Clashes Spur Coverage of Wall Street Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Clyde Haberman (October 10, 2011). "A New Generation of Dissenters". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Overtime, Solidarity and Complaints in Wall St. Protests. New York Times. October 13, 2011.

- ^ Rosen, Daniel Edward, "Is Ray Kelly’s NYPD Spinning Out of Control?", The [New York] Observer, 11/01/2011 6:39pm. 2011-11-03.

- ^ Al Baker, Colin Moynihan and Sarah Maslin Nir (October 1, 2011). "Police Arrest More Than 700 Protesters on Brooklyn Bridge". New York Times.

- ^ "Hundreds freed after New York Wall Street protest". BBC News. BBC. October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ ELIZABETH A. HARRIS (October 5, 2011). "Citing Police Trap, Protesters File Suit". The New York Times. p. A25. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street protests: Police make arrests, use pepper spray as some activists storm barricade". Daily News. New York. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Matt Wells and Karen McVeigh (October 5, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: thousands march in New York | World news | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Pullella, Phillip (October 15, 2011). "Wall Street protests go global; riots in Rome". Reuters.

- ^ ""Occupy" protests go global, turn violent". CBS News. October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Hawley, Chris (October 16, 2011.) "Thousands of ‘Occupy‘ protesters fill New York Times Square." Chicago Sun-Times. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ (October 16, 2011.) "Occupy Wall Street has raised $300,000." CBS News. Accessed October 2011.

- ^ Associated Press October 16, 2011, 11:02 pm (July 13, 2011). "Hundreds arrested in 'Occupy' protests". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Occupy Wall Street: How long can it last?". CNN. October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Bulwa, Demian (October 25, 2011). "Police clear Occupy Oakland camps, arrest dozens". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ JESSE, McKINLEY (October 27, 2011). "Some Cities Begin Cracking Down on 'Occupy' Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Romney, Lee (10/28/11). "Occupy Oakland regroups; injured Iraq war veteran recovering". LA Times. Retrieved 11/15/11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Kurpnick, Nick (10/27/11). "Occupy Oakland: Officials shift into damage control". Oakland Tribune. Retrieved 10/27/11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "BBC News — US Occupy protesters clash with police at Oakland port". Bbc.co.uk. October 27, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Occupy Wall Street Protests CBS News. 15 Nov 2011. Last accessed 16 Nov 2011.

- ^ Estes, Adam Clark (November 16, 2011). "Press Is Not Forgetting the Journalists Arrested at Zuccotti Park". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ McCarthy, Megan (November 17, 2011). "Bloomberg Spokesperson Admits Arresting Credentialed Reporters, Reading The Awl". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Several Journalists Among Those Arrested During Zuccotti Park Raid". CBSNewsYork/AP. CBS News. November 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Ventura, Michael (November 16, 2011). "DNAinfo.com Journalists Arrested While Covering OWS Police Raids". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Memmott, Mark (November 15, 2011). "New York Police Clear Occupy Wall Street Protesters From Park". NPR. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Journalists detained at NYC Occupy protests". The Wall Street Journal. Associated Press. November 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Malsin, Jared (November 15, 2011). "Reporter for The Local Is Arrested During Occupy Wall Street Clearing". NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Weiner, Juli (November 15, 2011). "Journalists, Among Those a Vanity Fair Correspondent, Arrested While Covering Occupy Wall Street". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Siegal, Ida (November 16, 2011). "Councilman Rodriguez Gives Details of His Occupy Wall Street Arrest". WNBC. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnston, Garth (November 15, 2011). "Police Arrest OWS Reporter As He Pleads "I'm A Reporter!"". Gothamist. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Exclusive Video: Inside Police Lines at the Occupy Wall Street Eviction". Mother Jones. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ David Badash. "Defiant NYC Mayor Bloomberg To Occupy Protestors: 'No Right Is Absolute'". The New Civil Rights Movement. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Stableford, Dylan (November 17, 2011). "Press clash with police during Occupy Wall Street raid; seven journalists arrested". The Cutline. Yahoo News. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Willis, Amy (November 15, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street eviction: as it happened". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

CBS News NY News Desk tells me their helicopter was forced down by NYPD -- they had to go down for fuel but weren't allowed back up. #ows

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gitlin, Sarah (November 15, 2011). "Reoccupy Wall Street". The Columbia Daily Spectator. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

A CBS helicopter that tried to cover the eviction aerially was forced to leave the airspace over the park by the NYPD, depriving the world of a view of what, exactly, the police were doing.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Journalists obstructed from covering OWS protests". Committee to Protect Journalists. November 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

Lindsey Christ, a reporter for the TV channel NY1, told the Times she witnessed police officers put a New York Post reporter "in a choke-hold."

- ^ a b The Washington Post, 2011 Nov. 15, Bloomberg’s Disgraceful Eviction of Occupy Wall Street

- ^ "SPJ condemns arrests of journalists at Occupy protests". Society of Professional Journalists. November 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Human rights group concerned over journalists' arrests at Occupy protests". Huffington Post. Associated Press. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Journalists arrested and obstructed again during Occupy Wall Street camp eviction". Reporters Without Borders. November 16, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Office of the Special Rappoteur Expresses Concern over Arrests and Assaults on Journalists Covering Protests in the United States" (Press release). Organization of American States. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ 11/21/11. "Media upset at NYPD for treatment of reporters at OWS — am New York". Amny.com. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ Al Jazeera, 16 Nov. 2011, The People's Library and the Future of OWS: The Massive Library Carted Away by Authorities at Zuccotti Park is a Formidable Weapon in Occupy Wall Street's Arsenal

- ^ Democracy Now, 15 Nov. 2011, Inside Occupy Wall Street Raid: Eyewitnesses Describe Arrests, Beatings as Police Dismantle Camp

- ^ "Occupy is here to stay". SuperMomWannabe.com. November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Tuesday, November 15 - msnbc tv — Rachel Maddow show — msnbc.com". MSNBC. November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Daily Kos (November 18, 2011) Irony of What Bloomberg’s Done, Threw out Fahrenheit 451

- ^ Submit. "Who Smashed the Laptops from Occupy Wall Street? Inside the NYPD's Lost and Found | Motherboard". Motherboard.tv. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Jardin, Xeni. "One week after attending NY Public Library gala, Bloomberg destroys #OWS library containing honorees' books (and his own)". Boing Boing. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam. "Occupy Wall Street: protesters regroup after eviction — Wednesday 16 November | World news | guardian.co.uk". Guardiannews.com. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Christopher Robbins (November 19, 2011). "Did The City Purposefully Destroy Occupy Wall Street's Property?". Gothamist. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Newman, Andy (November 15, 2011). "Updates on the Clearing of Zuccotti Park — NYTimes.com". New York City;Zuccotti Park (NYC): Cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Police Clear Zuccotti Park of Protesters The New York Times. 15 Nov 2011. Last accessed 16 Nov 2011.

- ^ Voorhees, Josh (November 17, 2011). "Re-Energized OWS Protesters Stage Nationwide "Day of Action"". Slate. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mirkinson, Jack (November 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street November 17: Journalists Arrested, Beaten By Police". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Jilani, Zaid (November 17, 2011). "Reporters For Right-Wing Publication Daily Caller Beaten By NYPD, Helped By Protesters". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Les Christie (December 6, 2011). "Occupy protesters take over foreclosed homes". CNNMoney. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ^ Liza Featherstone. "Occupy Education". The Nation. Retrieved December 25, 2011.

- ^ Babka, Jim (January 4, 2012). [tenthamendmentcenter.com/2012/01/04/ndaa-open-season-for-the-police-state/ "NDAA Open Season for the Police State"]. Tenth Amendment Centre. Retrieved January 06, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) - ^ Simon, Amanda (December 31st, 2011). "President Obama Signs Indefinite Detention Into Law". ACLU. Retrieved January 06, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Harshbarger, Rebecca (January 3, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street protesters rally then busted in Grand Central". New York Post. Retrieved January 04, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|publisher=|publisher=(help)

External links

- Occupy websites

- NYC General Assembly– The official website of the General Assembly at #OccupyWallStreet

- Occupy Wall Street . org– unofficial website produced by affinity group within #OWS

- Adbusters page– A listing of websites and updates

- Occupy Together– A hub for events occurring across the U.S.

- OccupyTV's YouTube Channel

- Related websites

- OccupyWiki.info– Wiki on the Occupy movement

- [http://www.wikioccupy.org – Wiki on the Occupy movement

- OccupyWiki.org– Directory and information

- Occupy Directory– Google Documents spreadsheet

- American Rattlesnake– Archive Of Photo Essays Relating to Occupy Wall Street

- Charts: Here's What The Wall Street Protesters Are So Angry About...– from Business Insider

- Occupy Wall Street Videos– The growing and expanding movement captured on video

- "Occupy" photographs from around the nation– from the Denver Post

- Inequality.org– from Program on Inequality and the Common Good, an Institute for Policy Studies project

- The Equality Trust (UK)– An organization for reducing income inequality in the United Kingdom

- In Re Waller Order to Show Cause and Temporary Restraining Order of November 15, 2011 from the National Lawyer's Guild website

- Decision of November 15, 2011 overturning the TRO in Matter of Waller v City of New York from the New York State Unified Court System website

- Occupy Wall Street Art & Culture– The hub for OWS-related film, art, music & graphic design.