Bayonet

A bayonet (from French baïonnette) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.[1] From the 17th century to World War I, it was considered[by whom?] a primary weapon for infantry attacks. Today it is considered an ancillary weapon or a weapon of last resort.

History

The term bayonette itself dates back to the mid-to-late 16th century, but it is not clear whether bayonets at the time were knives that could be fitted to the ends of firearms, or simply a type of knife. For example, Cotgrave's 1611 Dictionarie describes the bayonet as "a kind of small flat pocket dagger, furnished with knives; or a great knife to hang at the girdle". Likewise, Pierre Borel wrote in 1655 that a kind of long-knife called a bayonette was made in Bayonne but does not give any further description.[2]

Plug bayonets

The first recorded instance of a bayonet proper is found in the Chinese military treatise, Binglu published in 1606. It was in the form of the Son-and-mother gun, a breech-loading musket that was issued with a roughly 57.6 cm (22.7 in) long plug bayonet, giving it an overall length of 1.92 m (6 ft 4 in) with the bayonet attached. It was labelled as a "gun-blade" (traditional Chinese: 銃刀; simplified Chinese: 铳刀) with it being described as a "short sword that can be inserted into the barrel and secured by twisting it slightly" that it is to be used "when the battle have depleted both gunpowder and bullets as well as fighting against bandits, when forces are closing into melee or encountering an ambush" and if one "cannot load the gun within the time it takes to cover two bu (3.2 meters) of ground they are to attach the bayonet and hold it like a spear".[3][4]

Early bayonets were of the "plug" type, where the bayonet was fitted directly into the barrel of the musket.[5][6][7] This allowed light infantry to be converted to heavy infantry and hold off cavalry charges. The bayonet had a round handle that slid directly into the musket barrel. This naturally prevented the gun from being fired. The first known mention of the use of bayonets in European warfare was in the memoirs of Jacques de Chastenet, Vicomte de Puységur.[8] He described the French using crude 1-foot (0.30 m) plug bayonets during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).[8] However, it was not until 1671 that General Jean Martinet standardized and issued plug bayonets to the French regiment of fusiliers then raised. They were issued to part of an English dragoon regiment raised in 1672, and to the Royal Fusiliers when raised in 1685.[9]

Socket bayonets

The major problem with plug bayonets was that when attached they made it impossible to fire the musket, requiring soldiers to wait until the last possible moment before a melee to fix the bayonet. The defeat of forces loyal to William of Orange by Jacobite Highlanders at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689 was due (among other things) to the use of the plug bayonet.[6][9] The Highlanders closed to 50 metres, fired a single volley, dropped their muskets, and using axes and swords quickly overwhelmed the loyalists before they had time to fix bayonets. Shortly thereafter, the defeated leader, Hugh Mackay, is believed to have introduced a socket bayonet of his own invention. Soon "socket" bayonets would incorporate both socket mounts and an offset blade that fit around the musket's barrel, which allowed the musket to be fired and reloaded while the bayonet was attached.

An unsuccessful trial with socket or zigzag bayonets was made after the Battle of Fleurus in 1690, in the presence of King Louis XIV, who refused to adopt them, as they had a tendency to fall off the musket. Shortly after the Peace of Ryswick (1697), the English and Germans abolished the pike and introduced socket bayonets.[9] The British socket bayonet had a spike with a triangular cross-section rather than a flat blade, with a flat side towards the muzzle and two fluted sides outermost to a length of 15 inches (38 cm). It had no lock to keep it fast to the muzzle, and was well-documented for falling off in the heat of battle.[6]

By the 18th century, socket bayonets had been adopted by most European armies. In 1703, the French infantry adopted a spring-loaded locking system that prevented the bayonet from accidentally separating from the musket. A triangular blade was introduced around 1715 and was stronger than the previous single or double-edged model.

Sword bayonets

The 19th century introduced the concept of the sword bayonet, a long-bladed weapon with a single- or double-edged blade that could also be used as a shortsword. Its initial purpose was to ensure that riflemen could form an infantry square properly to fend off cavalry attacks when in ranks with musketmen, whose weapons were longer. A prime early example of a sword bayonet-fitted rifle is the British Infantry Rifle of 1800–1840, later known as the "Baker Rifle". The hilt usually had quillons modified to accommodate the gun barrel and a hilt mechanism that enabled the bayonet to be attached to a bayonet lug. A sword bayonet could be used in combat as a side arm. When attached to the musket or rifle, it effectively turned almost any long gun into a spear or glaive, suitable not only for thrusting but also for slashing.

While the British Army eventually discarded the sword bayonet, the socket bayonet survived the introduction of the rifled musket into British service in 1854. The new rifled musket copied the French locking ring system.[6] The new bayonet proved its worth at the Battle of Alma and the Battle of Inkerman during the Crimean War, where the Imperial Russian Army learned to fear it.[6]

From 1869, some European nations began to develop new bolt-action breechloading rifles (such as the Chassepot) and sword bayonets suitable for mass production and for use by police, pioneer, and engineer troops.[10] The decision to redesign the bayonet into a short sword was viewed by some as an acknowledgement of the decline in importance of the fixed bayonet as a weapon in the face of new advances in firearms technology.[11] As a British newspaper put it, "the committee, in recommending this new sword bayonet, appear to have had in view the fact that bayonets will henceforth be less frequently used than in former times as a weapon of offence and defence; they desired, therefore, to substitute an instrument of more general utility."[11]

Multipurpose bayonets

One of these multipurpose designs was the 'sawback' bayonet, which incorporated saw teeth on the spine of the blade.[10] The sawback bayonet was intended for use as a general-purpose utility tool as well as a weapon; the teeth were meant to facilitate the cutting of wood for various defensive works such as barbed-wire posts, as well as for butchering livestock.[1][11][12][13] It was initially adopted by the German states in 1865; until the middle of WWI approximately 5% of every bayonet style was complemented with a sawback version, for example in Belgium in 1868, Great Britain in 1869 and Switzerland in 1878 (Switzerland introduced their last model in 1914).[1][11][12][13][14] The original sawback bayonets were typically of the heavy sword-type, they were issued to engineers, with to some extent the bayonet aspect being secondary to the "tool" aspect. Later German sawbacks were more of a rank indicator than a functional saw. The sawback proved relatively ineffective as a cutting tool, and was soon outmoded by improvements in military logistics and transportation; most nations dropped the sawback feature by 1900.[1] The German army discontinued use of the sawback bayonet in 1917 after protests that the serrated blade caused unnecessarily severe wounds when used as a fixed bayonet.[1][13]

The trowel or spade bayonet was another multipurpose design, intended for use both as an offensive weapon as well as a digging tool for excavating entrenchments.[15][16] From 1870, the US Army issued trowel bayonets to infantry regiments based on a design by Lieutenant-Colonel Edmund Rice, a US Army officer and Civil War veteran, which were manufactured by the Springfield Armory.[17] Besides its utility as both a fixed bayonet and a digging implement, the Rice trowel bayonet could be used to plaster log huts and stone chimneys for winter quarters; sharpened on one edge, it could cut tent poles and pins.[17] Ten thousand were eventually issued, and the design saw service during the 1877 Nez Perce campaign.[18] Rice was given leave in 1877 to demonstrate his trowel bayonet to several nations in Europe.[18] One infantry officer recommended it to the exclusion of all other designs, noting that "the intrenching [sic] tools of an army rarely get up to the front until the exigency for their use has passed."[17] The Rice trowel bayonet was declared obsolete by the US Army in December 1881.[18]

"Reach" controversy

Prior to World War I, bayonet doctrine was largely founded upon the concept of "reach"; that is, a soldier's theoretical ability, by use of an extremely long rifle and fixed bayonet, to stab an enemy soldier without having to approach within reach of his opponent's blade.[1][19][20] A combined length of rifle and bayonet longer than that of the enemy infantryman's rifle and attached bayonet, like the infantryman's pike of bygone days, was thought to impart a tactical advantage on the battlefield.[1][20][21][22]

In 1886, the French army introduced a 52-centimetre-long (20.5 in) quadrangular épée spike for the bayonet of the Lebel Model 1886 rifle, the Épée-Baïonnette Modèle 1886, resulting in a rifle and bayonet with an overall length of six feet (1.8 m). Germany responded by introducing a long sword bayonet for the Model 1898 Mauser rifle, which had a 29-inch barrel. The bayonet, the Seitengewehr 98, had a 50 cm (19.7-inch) blade.[21] With an overall length of 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m), the German army's rifle/bayonet combination was second only to the French Lebel for overall 'reach'.[21]

After 1900, Switzerland, Britain, and the United States adopted rifles with barrel lengths shorter than that of a rifled musket, but longer than that of a carbine.[1][23] These were intended for general use by infantry and cavalry.[23] The "reach" of the new short rifles with attached bayonet was reduced.[1] Britain introduced the shortened Lee–Enfield rifle, the SMLE, in 1904.[1][23] The German M1898 Mauser rifle and attached sword bayonet was 20 cm (eight inches) longer than the SMLE and its P1903 bayonet, which used a twelve-inch (30 cm) blade.[1][24] While the British P1903 and its similar predecessor, the P1888, was satisfactory in service, criticism soon arose regarding the shortened reach.[1][21][23][25] One military writer of the day warned: "The German soldier has eight inches the better of the argument over the British soldier when it comes to crossing bayonets, and the extra eight inches easily turns the battle in favour of the longer, if both men are of equal skill."[21]

In 1905, the German Army adopted a shortened 37-centimetre-long (14.5 in) bayonet, the Seitengewehr 98/06 for engineer and pioneer troops, and in 1908, a short rifle as well, the Karabiner Model 1898AZ, which was produced in limited quantities for the cavalry, artillery, and other specialist troops.[26] However, the long-barreled 98 Mauser rifle remained in service as the primary infantry small arm.[27] Moreover, German military authorities continued to promote the idea of outreaching one's opponent on the battlefield by means of a longer rifle/bayonet combination, a concept prominently featured in its infantry bayonet training doctrines.[22] These included the throw point or extended thrust-and-lunge attack.[28] Using this tactic, the German soldier dropped into a half-crouch, with the rifle and fixed bayonet held close to the body.[28] In this position the soldier next propelled his rifle forward, then dropped the supporting hand while taking a step forward with the right foot, simultaneously thrusting out the right arm to full length with the extended rifle held in the grip of the right hand alone.[28] With a maximum 'kill zone' of some eleven feet, the throw point bayonet attack gave an impressive increase in 'reach', and was later adopted by other military forces, including the U.S. Army.[28][29]

In response to criticism over the reduced reach of the SMLE rifle and bayonet, British ordnance authorities introduced the P1907 bayonet in 1908, which had an elongated blade of some seventeen inches to compensate for the reduced overall length of the SMLE rifle.[1][20][23][30][31] The 1907 bayonet was essentially a copy of the Japanese Type 30 bayonet, Britain having purchased a number of Japanese type 30 rifles for the Royal Navy during the preceding years.[32] U.S. authorities in turn adopted a long (16-in. blade) bayonet for the M1903 Springfield short rifle, the M1905 bayonet; later, a long sword bayonet was also provided for the M1917 Enfield rifle.[25]

Reversal in opinion

The experience of World War I reversed opinion on the value of long rifles and bayonets in typical infantry combat operations.[24][31][33][34] Whether in the close confines of trench warfare, night time raiding and patrolling, or attacking across open ground, soldiers of both sides soon recognized the inherent limitations of a long and ungainly rifle and bayonet when used as a close-quarters battle weapon.[24][31][33][34] Once Allied soldiers had been trained to expect the throw point or extended thrust-and-lunge attack, the method lost most of its tactical value on the World War I battlefield.[28] It required a strong arm and wrist, was very slow to recover if the initial thrust missed its mark, and was easily parried by a soldier who was trained to expect it, thus exposing the German soldier to a return thrust which he could not easily block or parry.[28][35][36] Instead of longer bayonets, infantry forces on both sides began experimenting with other weapons as auxiliary close-quarter arms, including the trench knife, handgun, hand grenade, and entrenching tool.[33][37]

Soldiers soon began employing the bayonet as a knife as well as an attachment for the rifle, and bayonets were often shortened officially or unofficially to make them more versatile and easier to use as tools, or to maneuver in close quarters.[1][31][33][34] During World War II, bayonets were further shortened into knife-sized weapons in order to give them additional utility as fighting or utility knives.[1] The vast majority of modern bayonets introduced since World War II are of the knife bayonet type.[1]

Bayonet charge

The development of the bayonet in the mid-17th century led to the bayonet charge becoming the main infantry tactic through the 19th century and into the 20th. As early as the 19th century, military scholars were already noting that most bayonet charges did not result in close combat. Instead, one side usually fled before actual bayonet fighting ensued. The act of fixing bayonets has been held to be primarily connected to morale, the making of a clear signal to friend and foe of a willingness to kill at close quarters.[38]

The bayonet charge was above all a tool of shock. While charges were reasonably common in 18th and 19th century warfare, actual combat between formations with their bayonets was so rare as to be effectively nonexistent. Usually, a charge would only happen after a long exchange of gunfire, and one side would break and run before contact was actually made. Sir Charles Oman, nearing the end of his history of the Peninsular War in which he had closely studied hundreds of battles and combats, only discovered a single example of, in his words, "one of the rarest things in the Peninsular War, a real hand-to-hand fight with the white weapon." Infantry melees were much more common in close country – towns, villages, earthworks and other terrain which reduced visibility to such ranges that hand-to-hand fighting was unavoidable. These melees, however, were not bayonet charges per se, as they were not executed or defended against by regular bodies of orderly infantry; rather they were a chaotic series of individual combats where musket butts and fists were used alongside bayonets.[39]

Napoleonic wars

The bayonet charge was a common tactic used during the Napoleonic wars. Despite its effectiveness, a bayonet charge did not necessarily cause substantial casualties through the use of the weapon itself. Detailed battle casualty lists from the 18th century showed that in many battles, less than 2% of all wounds treated were caused by bayonets.[40] Antoine-Henri Jomini, a celebrated military author who served in numerous armies during the Napoleonic period, stated that the majority of bayonet charges in the open resulted with one side fleeing before any contact was made. Combat with bayonets did occur, but mostly on a small scale when units of opposing sides encountered each other in a confined environment, such as during the storming of fortifications or during ambush skirmishes in broken terrain.[41] In an age of fire by massed volley, when compared to random unseen bullets, the threat of the bayonet was much more tangible and immediate – guaranteed to lead to a personal gruesome conclusion if both sides persisted. All this encouraged men to flee before the lines met. Thus, the bayonet was an immensely useful weapon for capturing ground from the enemy, despite seldom actually being used to inflict wounds.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War (1861–1865) the bayonet was found to be responsible for less than 1% of battlefield casualties,[42] a hallmark of modern warfare. The use of bayonet charges to force the enemy to retreat was very successful in numerous small unit engagements at short range in the American Civil War, as most troops would retreat when charged while reloading. Although such charges inflicted few casualties, they often decided short engagements, and tactical possession of important defensive ground features. Additionally, bayonet drill could be used to rally men temporarily unnerved by enemy fire.[43]

While the overall Battle of Gettysburg was won by the Union armies due to a combination of terrain and massed artillery fire, a decisive point on the second day of the battle hinged on a bayonet charge at Little Round Top when the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, running short of musket ammunition, charged downhill, surprising and capturing many of the surviving soldiers of the 15th Alabama Infantry Regiment and other Confederate regiments.

Going over the top

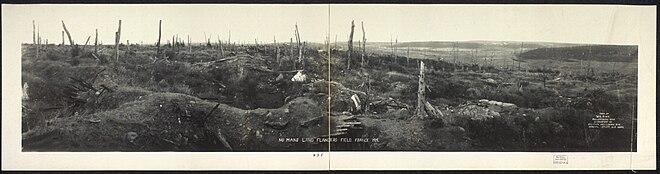

The popular image of World War I combat is of a wave of soldiers with bayonets fixed, "going over the top" and charging across no man's land into a hail of enemy fire. Although this was the standard method of fighting early in the war, it was rarely successful. British casualties on the first day of the Battle of the Somme were the worst in the history of the British army, with 57,470 British casualties, 19,240 of whom were killed.[44][45]

During World War I, no man's land was often hundreds of yards across.[46] The area was usually devastated by the warfare and riddled with craters from artillery and mortar shells, and sometimes contaminated by chemical weapons. Heavily defended by machine guns, mortars, artillery and riflemen on both sides, it was often covered with barbed wire and land mines, and littered with the rotting corpses of those who were not able to make it across the sea of bullets, explosions and flames. A bayonet charge through no man's land often resulted in the total annihilation of entire battalions.

Banzai charges

The advent of modern warfare in the 20th century made bayonet charges dubious affairs. During the Siege of Port Arthur (1904–05), the Japanese used suicidal human wave attacks against Russian artillery and machine guns,[47] suffering massive casualties.[48] One description of the aftermath was that a "thick, unbroken mass of corpses covered the cold earth like a [carpet]".[49]

However, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese were able to effectively use bayonet charges against poorly organized and lightly armed Chinese troops. "Banzai charges" became an accepted military tactic where Japanese forces were able to routinely rout larger Chinese forces.[50]

In the early stages of the Pacific War, a sudden banzai charge might overwhelm small groups of enemy soldiers unprepared for such an attack. But, by the end of the war, against well organized and heavily armed Allied forces, a banzai charge inflicted little damage while its participants suffered horrendous losses. At best, they were conducted as a last resort by small groups of surviving soldiers when the main battle was already lost. At worst, they wasted valuable resources in men and weapons, which hastened defeat.

Some Japanese commanders, such as General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, recognized the futility and waste of such attacks and expressly forbade their men from carrying them out. Indeed, the Americans were surprised that the Japanese did not employ banzai charges at the Battle of Iwo Jima.[51][52]

Human wave attack

The term "human wave attack" was often misused to describe the Chinese short attack[53]—a combination of infiltration and the shock tactics employed by the PLA during the Korean War.[54] A typical Chinese short attack was carried out at night by sending a series of small five-men fireteams to attack the weakest point of an enemy's defenses.[54] The Chinese assault team would crawl undetected within grenade range, then launch surprise attacks with fixed bayonets against the defenders in order to breach the defenses by relying on maximum shock and confusion.[54]

If the initial shock failed to breach the defenses, additional fireteams would press on behind them and attack the same point until a breach was created.[54] Once penetration was achieved, the bulk of the Chinese forces would move into the enemy rear and attack from behind.[55] Due to primitive communication systems and tight political controls within the Chinese army, short attacks were often repeated until either the defenses were penetrated or the attackers were completely annihilated.[54]

This persistent attack pattern left a strong impression on UN forces that fought in Korea, giving birth to the description of "human wave".[56] The term "human wave" was later used by journalists and military officials to convey the image of the American soldiers being assaulted by overwhelming numbers of Chinese on a broad front, which is inaccurate when compared with the normal Chinese practice of sending successive series of small teams against a weak point in the line.[57] It was in fact rare for the Chinese to actually use densely concentrated infantry formations to absorb enemy firepower.[58]

Last hurrahs

One use the Germans in World War II made of bayonets was to search for people in hiding. One person hiding in a house in the Netherlands wrote: The Germans made lots of noise as they came upstairs, and they stabbed their bayonets into the wall. Then what we'd always feared actually happened: A bayonet went through the thin wallpaper above the closet, exposing the three people who were hiding there. "Raus!" cried the Germans. "Out!"[59]

During the Korean War, the French Battalion and Turkish Brigade used bayonet charges against their enemy.[60] In 1951, United States Army officer Lewis L. Millett led soldiers of the US Army's 27th Infantry Regiment in taking out a machine gun position with bayonets. Historian S. L. A. Marshall described the attack as "the most complete bayonet charge by American troops since Cold Harbor". Out of about 50 enemy dead, roughly 20 were found to have been killed by bayonets, and the location subsequently became known as Bayonet Hill.[61] This was the last bayonet charge by the US Army. For his leadership during the assault, Millett was awarded the Medal of Honor. The medal was formally presented to him by President Harry S. Truman in July 1951.[62] He was also awarded the Army's second-highest decoration, the Distinguished Service Cross, for leading another bayonet charge in the same month.[63]

In 1982, the British Army mounted bayonet charges during the Falklands War, notably the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment during the Battle of Mount Longdon and the 2nd Battalion, Scots Guards during the final assault of Mount Tumbledown.

In 1995, during the Siege of Sarajevo, French Marine infantrymen from the 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment carried out a bayonet charge against the Serbian forces at the Battle of Vrbanja bridge.[64] Actions led by the regiment allowed the United Nations blue helmets to exit from a passive position due to a first time engagement in hostile responses. Two fatalities resulted from this event with seventeen others wounded.

During the Second Gulf War and the war in Afghanistan, the British Army units mounted bayonet charges.[65] In 2004 in Iraq at the Battle of Danny Boy, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders bayonet-charged mortar positions filled with over 100 Mahdi Army members. The ensuing hand-to-hand fighting resulted in an estimate of over 40 insurgents killed and 35 bodies collected (many floated down the river) and nine prisoners. Sergeant Brian Wood, of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment, was awarded the Military Cross for his part in the battle.[66]

In 2009, Lieutenant James Adamson of the Royal Regiment of Scotland was awarded the Military Cross for a bayonet charge while on a tour of duty in Afghanistan: after shooting one Taliban fighter dead, Adamson had run out of ammunition when another enemy appeared. He immediately charged the second Taliban fighter and bayoneted him.[67] In September 2012, Lance Corporal Sean Jones of The Princess of Wales's Regiment was awarded the Military Cross for his role in a bayonet charge which took place in October 2011.[68][69]

Contemporary bayonets

Today the bayonet is rarely used in one-to-one combat.[70][71][72] Despite its limitations, many modern assault rifles (including bullpup designs) retain a bayonet lug and the bayonet is still issued by many armies. The bayonet is still used for controlling prisoners, or as a weapon of last resort.[70] In addition, some authorities have concluded that the bayonet serves as a useful training aid in building morale and increasing desired aggressiveness in troops.[73][74]

Today's bayonets often double as multi-purpose utility knives, bottle openers or other tools. Issuing one modern multi-purpose bayonet/knife is also more cost effective than issuing separate specialty bayonets, and field/combat knives.

USSR

The original AK-47 has an adequate but unremarkable bayonet. However, the AKM Type I bayonet (introduced in 1959) was an improvement of the original design.[75] It has a Bowie style (clip-point) blade with saw-teeth along the spine, and can be used as a multi-purpose survival knife and wire-cutter when combined with its steel scabbard.[75][76] The AK-74 bayonet 6Kh5 (introduced in 1983) represents a further refinement of the AKM bayonet. "It introduced a radical blade cross-section, that has a flat milled on one side near the edge and a corresponding flat milled on the opposite side near the false edge."[75] The blade has a new spear point and an improved one-piece moulded plastic grip, making it a more effective fighting knife.[75] It also has saw-teeth on the false edge and the usual hole for use as a wire-cutter.[75] The wire cutting versions of the AK bayonets each have an electrically insulated handle and an electrically insulated part of the scabbard, so it can be used to cut an electrified wire.

United States

The American M16 rifle used the M7 bayonet which is based on earlier designs such as the M4, M5 and M6 models, all of which are direct descendants of the M3 Fighting Knife and have a spear-point blade with a half sharpened secondary edge. The newer M9 has a clip-point blade with saw-teeth along the spine, and can be used as a multi-purpose knife and wire-cutter when combined with its scabbard. It can even be used by troops to cut their way free through the relatively thin metal skin of a crashed helicopter or airplane. The current USMC OKC-3S bayonet bears a resemblance to the Marines' iconic Ka-Bar fighting knife with serrations near the handle.

People's Republic of China

The AK-47 assault rifle was copied by China as the Type 56 assault rifle and include an integral folding spike bayonet, similar to the SKS rifle.[77] Some Type 56s may also use the AKM Type II bayonet.[77][78] The latest Chinese rifle, the QBZ-95, has a multi-purpose knife bayonet similar to the US M9.

Belgium

The FN FAL has two types of bayonet. The first is a traditional spear point bayonet. The second is the Type C socket bayonet introduced in the 1960s.[79] It has a hollow handle that fits over the muzzle and slots that lined up with those on the FALs 22 mm NATO-spec flash hider.[79] Its spear-type blade is offset to the side of the handle to allow the bullet to pass beside the blade.[79]

United Kingdom

The current British L3A1 socket bayonet is based on the FN FAL Type C socket bayonet with a clip-point blade.[80] It has a hollow handle that fits over the SA80/L85 rifle's muzzle and slots that lined up with those on the flash eliminator. The blade is offset to the side of the handle to allow the bullet to pass beside the blade. It can also be used as a multi-purpose knife and wire-cutter when combined with its scabbard.[70] The scabbard also has a sharpening stone and folding saw blade.[70] The use of contemporary bayonets by the British army was noted during the Afghanistan war in 2004.[69]

Germany

The H&K G3 rifle uses two types of bayonets, both of which mount above the G3's barrel.[81] The first is the standard G3 bayonet which has a blade similar to the American M7.[81] The second is an EICKHORN KCB-70 type multi-purpose knife bayonet, featuring a clip-point with saw-back, a wire-cutter scabbard and a distinctive squared handgrip.[81] For the H&K G36 there was little use of modified AKM type II blade bayonets from stocks of the former Nationale Volksarmee (National People's Army) of East Germany. The original muzzle-ring was cut away and a new, large diameter muzzle ring welded in place. The original leather belt hanger was replaced by a complex web and plastic belt hanger designed to fit the West German load bearing equipment.[82]

Austria

The Steyr AUG uses two types of bayonet. The first and most common is an Eickhorn KCB-70 type multi-purpose bayonet with an M16 bayonet type interface. The second are the Glock Feldmesser 78 (Field Knife 78) and the Feldmesser 81 (Survival Knife 81), which can also be used as a bayonet, by engaging a socket in the pommel (covered by a plastic cap) into a bayonet adapter that can be fitted to the AUG rifle.[83][84][85] These bayonets are noteworthy, as they were meant to be used primarily as field or survival knives and use as a bayonet was a secondary consideration. They can also be used as throwing knives and have a built-in bottle opener in the crossguard.[86][87]

France

The French use a more traditional spear point bayonet with the current FAMAS bayonet which is nearly identical to that of the M1949/56 bayonet.[88] The new French H&K 416F rifle uses the Eickhorn "SG 2000 WC-F", a multi-purpose combat knife/bayonet (similar to the KM2000) with a wire cutter.[89] It weighs 320 g (0.7 lb), is 30.0 cm (11.8 in) long with a half serrated 17.3 cm (6.8 in) blade for cutting through ropes.[89] The synthetic handle and sheath have electrical insulation that protects up to 10,000 volts. The sheath also has a diamond blade sharpener.

Photo gallery

-

Multi-purpose AKM Type I bayonet of the Nationale Volksarmee shown cutting a wire

-

Afghan policeman with AKM and AKM Type II bayonet.

-

The US M5 bayonet and scabbard used with the M1 Garand

-

The US M6 bayonet and scabbard used with the M14 rifle

-

M7 Bayonet and M8A1 Sheath used with the M16 rifle

-

M9 bayonet and scabbard in wire-cutter configuration.

-

M9 bayonet fitted M4 carbine firing during secondary target drills.

-

The USMC OKC-3S Bayonet

-

US Marines at bayonet practice.

-

Folding an SKS-type bayonet.

-

A Chinese sailor with a Type 56 with the integral folding spike bayonet, 1986.

-

Chinese soldier with QBZ-95 rifle and multi-purpose knife bayonet.

-

Early FN FAL and bayonet.

-

Kuwaiti soldier with his FN FAL rifle with bayonet.

-

British-issue L3A1 bayonet. Note the slot in the blade to attach the wire-cutter scabbard.

-

L3A1 scabbard. Note the lug to attach the bayonet for wire cutting.

-

British servicemen with fixed L3A1 bayonets on L85A2 rifles. The L3A1's blade is offset to permit firing.

-

Palace guard at the royal palace, Oslo. Note the G3 type rifle with bayonet over the barrel.

-

Glock field knife/bayonet and its scabbard. The upper crossguard is bent forward and can be used as a bottle opener.

-

Irish Army Honor Guard. Note Steyr AUG with EICKHORN KCB-70 type multi-purpose bayonet

-

Royal New Zealand Navy Guard of Honour. Note Individual Weapon Steyr with American M7 bayonets.

-

The Royal 22nd Regiment of Canada unfixing their bayonets.

-

Marines from Marine Barracks Washington D.C. fix their bayonets during rehearsals for the presidential inauguration.

Linguistic impact

The push-twist motion of fastening the older type of bayonet has given a name to:

- The "bayonet mount" used for various types of quick fastenings, such as camera lenses, also called a "bayonet connector" when used in electrical plugs.

- Several connectors and contacts including the bayonet-fitting light bulb that is common in the UK (as opposed to the continental European screw-fitting type).

- One type of connector for foil and sabre weapons used in modern fencing competitions is referred to as a "bayonet" connector.

In chess, an aggressive variation of the King's Indian Defence is known as the "Bayonet Attack".

The bayonet has become a symbol of military power. The term "at the point of a bayonet" refers to using military force or action to accomplish, maintain, or defend something (cf. Bayonet Constitution). Undertaking a task "with fixed bayonets" has this connotation of no room for compromise and is a phrase used particularly in politics.

Badges and insignias

The Australian Army 'Rising Sun' badge features a semicircle of bayonets. The Australian Army Infantry Combat Badge (ICB) takes the form of a vertically mounted Australian Army SLR (7.62mm self-loading rifle FN FAL) bayonet surrounded by an oval-shaped laurel wreath.[91] The US Army Combat Action Badge, awarded to personnel who have come under fire since 2001 and who are not eligible for the Combat Infantryman Badge (due to the fact that only Infantry personnel may be awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge), has a bayonet as its central motif.

The shoulder sleeve insignia for the 10th Mountain Division in the US Army features crossed bayonets. The US Army's 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team's shoulder patch features a bayonet wrapped in a wing, symbolizing their airborne status. The brigade regularly deploys in task forces under the name "Bayonet". The insignia of the British Army's School of Infantry is an SA80 bayonet against a red shield. It is worn as a Tactical recognition flash (TRF) by instructors at the Infantry Training Centre Catterick, the Infantry Battle School at Brecon and the Support Weapons School in Warminster.

The vocation tab collar insignia for the Singapore Armed Forces Infantry Formation utilizes two crossed bayonets. The bayonet is often used as a symbol of the Infantry in Singapore.

See also

- 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, known as the Bayonet Constitution

- Aiki-jō wooden staff used in the japanese martial art of Aikido, which in use resembles a bayonet more than a spear.

- Bayonet lug

- Combatives

- Jūkendō

- Spike bayonet

- Use of bayonets for crowd control

- Wilfred Owen mentions bayonets in the poem Soldier's Dream

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Brayley, Martin, Bayonets: An Illustrated History, Iola, WI: Krause Publications, ISBN 0-87349-870-4, ISBN 978-0-87349-870-8 (2004), pp. 9–10, 83–85.

- ^ H. Blackmore, Hunting Weapons, p. 50

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 456.

- ^ Binglu 《兵錄》, Scroll 12.

- ^ Norris, John (3 January 2016). Fix Bayonets!. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-8378-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Cold Steel – The History of the Bayonet". BBC News. 18 November 2002. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ Jones, Gareth, ed. (1 October 2012). Military History: The Definitive Visual Guide to the Objects of Warfare. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4654-1158-7.

- ^ a b "Bayonet History Timeline – 1647 First Military Use of the Bayonet". Worldbayonets.com. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bayonet". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Owen, John Ivor Headon, Brassey's Infantry Weapons of the World: Infantry Weapons and Combat Aids in Current Use by the Regular and Reserve Forces of All Nations, Bonanza Press, ISBN 0-517-24234-6, ISBN 978-0-517-24234-6 (1975), p. 265

- ^ a b c d "The Soldier's Side-Companion". Punch's Almanack for 1869. 57 (1465). London: Punch Publications Ltd: 54. 7 August 1869. hdl:2027/uc1.c2583869.

- ^ a b Knight, Edward H., Knight's American Mechanical Dictionary (Vol. 1), New York: J. B. Ford & Co. (1874), p. 252

- ^ a b c Rhodes, Bill, An Introduction to Military Ethics: A Reference Handbook, ABC CLIO LLC, ISBN 0-313-35046-9, ISBN 978-0-313-35046-7 (2009), pp. 13–14

- ^ Foulkes, Charles J., and Hopkinson, Edward C., Sword, Lance & Bayonet: A Record of the Arms of the British Army & Navy (2nd ed.), Edgware, Middlesex: Arms & Armour Press (1967) p. 113

- ^ Ripley, George, and Dana, Charles A., The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge (Vol. II), New York: D. Appleton & Co. (1873), p. 409

- ^ Board of Officers Assembled at St. Louis, Missouri, Schofield, J.M. (Maj. Gen.) President, Bayonets: Resume of the Proceedings of the Board, June 10, 1870, Ordnance Memoranda, Issue 11, United States Army Ordnance Dept., Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1870), p. 16

- ^ a b c Belknap, William W., Trowel-Bayonet, Letter from the Secretary of War In Answer to a Resolution of the House of April 4, 1872, The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session (1871–1872), Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1872), pp. 1–20

- ^ a b c McChristian, Douglas C., Uniforms, Arms, and Equipment: Weapons and Accouterments, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3790-8, ISBN 978-0-8061-3790-2 (2007), pp. 128–142

- ^ Hutton, Alfred, Fixed Bayonets: A Complete System of Fence for the British Magazine Rifle, London: William Clowes & Sons (1890), pp. v, 125, 131–132

- ^ a b c Barrett, Ashley W., "Lessons to be Learned by Regimental Officers from the Russo-Japanese War", "Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States", Volume 45, (March–April 1909), pp. 300–301.

- ^ a b c d e Hopkins, Albert A., Scientific American War Book: the Mechanism and Technique of Warfare, New York: Munn & Co. (1915) p. 141

- ^ a b Praktische Bajonett-Fechtschule: auf Grund der Bajonettir-Vorschrift für die Infanterie, Berlin: E. S. Mittler und Sohn (1889)

- ^ a b c d e Seton-Karr, Henry (Sir), "Rifle", Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co., Vol. 23 (Ref–Sai)(1911), p. 328

- ^ a b c Pegler, Martin and Chappell, Mike, Tommy 1914–18 (Vol. 16), New York: Osprey Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-85532-541-1, ISBN 978-1-85532-541-8 (1996), p. 16

- ^ a b Tilson, John Q. (Hon.), Weapons of Aerial Warfare: Speech By Hon. John Q. Tilson, Delivered June 1, 1917, United States House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1918), p. 84

- ^ James, Gary, "Germany's Karabiner 98AZ Archived 7 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine", Guns & Ammo (June 2010), retrieved 17 November 2011

- ^ Ezell, Edward C., Small Arms of the World: A Basic Manual of Small Arms, Volume 11, p. 502

- ^ a b c d e f Crossman, Edward C., "The Rifle of the Hun", Popular Mechanics, Vol. 30, No. 2 (1918), pp. 183–185.

- ^ Stacey, Cromwell (Capt.), "Training in Bayonet Fighting: Throw Point", U.S. Infantry Journal, Vol. 10, No. 6 (1914) pp. 870–871.

- ^ Notes on Naval Progress, Section II: Small Arms, General Information Series Volume 20, United States Office of Naval Intelligence, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (July 1901), p. 198

- ^ a b c d Regan, Paula (ed.), Weapon: A Visual History of Arms and Armor, London: Penguin Ltd. ISBN 0-7566-4219-1, ISBN 978-0-7566-4219-8 (2006), p. 284.

- ^ "1907 pattern bayonet". Royal Armouries. 27 November 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d McBride, Herbert W., A Rifleman Went to War, Plantersville, SC: Small Arms Technical Publishing Co. (1935), pp. 179–185, 197, 241–243, 335

- ^ a b c Knyvett, R. Hugh (Capt.), Over There with the Australians, originally published 1918, reprinted by The Echo Library, ISBN 978-1-4068-6694-0 (2011), pp. 152–153.

- ^ Moss, James Alfred, Manual of Military Training, Menasha, WI: George Banta Publishing Co. (1914), p. 161: "The adversary may attempt a greater extension in the thrust and lunge by quitting the grasp of his piece with the left hand and advancing the right as far as possible. When this is done, a sharp parry may cause him to lose control of his rifle, leaving him exposed to a counter-attack, which should follow promptly."

- ^ United States Marine Corps, U.S. Marine Combat Conditioning, United States Marine Corps Schools (Sep 1944), reprinted Skyhorse Publishing Inc., ISBN 1-60239-962-X, ISBN 9781602399624 (2011), p. 7: "The...'throw point' as it is sometimes called can be used to thrust from a distance an unarmed enemy who is running backwards away from you. This would probably be the only time you would actually thrust a man with a...'throw point'...because unless your enemy is off his guard and unless you have a very strong arm, there is too much chance of dropping the rifle or of his knocking it from your hands."

- ^ Beith, Ian H., "Modern Battle Tactics: Address Delivered April 9, 1917", National Service (June 1917), pp. 325, 328

- ^ Holmes, Richard (1987). Firing Line. Harmondsworth: Penguin. pp. 377–9. ISBN 978-0-14-008574-7.

- ^ Rory Muir, "Tactics and the Experience of Battle in the Age of Napoleon," pp. 86–88.

- ^ Lynn, John A. Giant of the Grand Siècle: The French Army, 1610–1715. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

- ^ Jomini, Antoine Henri. The Art of War. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1971. Print.

- ^ O'Connell, Robert L., "Arme Blanche", Military History Quarterly, Vol. 5, nº 1.

- ^ The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War

- ^ Edmonds 1993, p. 483.

- ^ Prior & Wilson 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Hamilton, John (2003), Trench Fighting of World War I, ABDO, p. 8, ISBN 978-1-57765-916-7

- ^ Miller, John H. (2 April 2014). American Political and Cultural Perspectives on Japan: From Perry to Obama. Lexington Books. pp. 41ff. ISBN 978-0-7391-8913-9.

- ^ Edgerton, Robert B. (1997). Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military. Norton. pp. 167ff. ISBN 978-0-393-04085-2.

- ^ Robert L. O'Connell; John H. Batchelor (2002). Soul of the Sword: An Illustrated History of Weaponry and Warfare from Prehistory to the Present. Simon and Schuster. pp. 243ff. ISBN 978-0-684-84407-7.

- ^ Carmichael, Cathie; Maguire, Richard C. (1 May 2015). The Routledge History of Genocide. ISBN 9781317514848.

- ^ Derrick, Wright (2006). The Battle for Iwo Jima. Sutton Publishing. p. 80.

- ^ According to military historian Shigetoki Hosoki, "This writer was stunned to find the following comments in the 'Iwo Jima Report', a collection of memoirs by Iwo Jima survivors. 'The men we saw weighed no more than thirty kilos and did not look human. Nonetheless, these emaciated soldiers who looked like they came from Mars faced the enemy with a force that could not be believed. I sensed a high morale.' Even under such circumstances, the underground shelters that the Japanese built proved advantageous for a while. Enemy mortar and bombing could not reach them ten meters underground. It was then that the Americans began to dig holes and poured yellow phosphorus gas into the ground. Their infantry was also burning its way through passages, slowly but surely, at the rate of ten meters per hour. A telegram has been preserved which says, 'This is like killing cockroaches.' American troops made daily advances to the north. On the evening of 16 March, they reported that they had completely occupied the island of Iwo Jima." Picture Letters from the Commander-in-Chief, page 237.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 363.

- ^ a b c d e Roe 2000, p. 435.

- ^ Alexander 1986, p. 311.

- ^ Appleman 1989, p. 353.

- ^ Appleman 1990, p. 362.

- ^ Marshall 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Prins Marcel & Steenhuis, Peter Henk, "Hidden," Arthur A. Levine Books, New York, Copyright 2011, page 35.

- ^ Grey, Jeffrey (1988). The Commonwealth Armies and the Korean War: An Alliance Study. Manchester University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7190-2611-9.

- ^ Lawrence, J.M. (19 November 2009). "Lewis Millett; awarded Medal of Honor after bayonet charge". The Boston Globe. Boston. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Ghiotto, Gene (14 November 2009). "Medal of Honor recipient Lewis Millett dies at age 88". The Press-Enterprise. Riverside, California. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (18 November 2009). "Daring soldier was awarded Medal of Honor". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "- granulés & pellets". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Sean Rayment (12 June 2004). "British battalion 'attacked every day for six weeks'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ Wyatt, Caroline (28 April 2009). "UK combat operations end in Iraq". BBC News.

- ^ "Military cross for bayonet charge". BBC News. 13 September 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Shropshire soldier Lance Cpl Jones awarded Military Cross". BBC News. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b Wills, Matthew (7 June 2021). "The Bayonet: What's the Point?". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kontis, George. "Are We Forever Stuck with the Bayonet?". Small Arms Defense Journal.

- ^ Hughes, Gordon; Jenkins, Barry; Buerlein, Robert A. (2006). Knives of War: An International Guide to Military Knives from World War I to the Present. Paladin Press. pp. 101–110.

- ^ Shillingford, Ron (2001). The Elite Forces Handbook of Unarmed Combat. St Martin's Press. pp. 175–179. ISBN 9780312264369.

- ^ U.S. Army Field Manual 3-25.150, 2002-12-18.

- ^ Major William Beaudoin, CD. "The Psychology of the Bayonet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e http://worldbayonets.com/Misc__Pages/ak_bayonets/ak_bayonets.html | Kalashnikov Bayonets Ralph E. Cobb, 2010

- ^ how to use the wire cutter on an akm /ak 47 bayonet. YouTube (16 July 2009). Retrieved on 2011-09-27.

- ^ a b Hogg, Ian V.; Weeks, John S. (2000). Military Small Arms of the 20th Century (7th ed.). Krause Publications. pp. 230–231.

- ^ "Chinese AK Bayonets". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c http://worldbayonets.com/Bayonet_Identification_Guide/fal_page/fal_bayonets.html%7CWorld[permanent dead link] Bayonets. FN FAL Bayonets

- ^ "FN-FAL Bayonets". worldbayonets.com.

- ^ a b c "Bayonet for Heckler & Koch rifles by R.D.C. Evans. October 2009" (PDF). Bayonet Studies Series. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Bayonets of Post-War Germany". worldbayonets.com.

- ^ "Bayonets of Austria". worldbayonets.com.

- ^ "World Bayonets. Austria. Image of Glock Knife mounted on Stryr AUG" (PDF).

- ^ Glock 78 field knife or bayonet Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Created on 23 July 2012. Written by Ramon A. Castella.

- ^ "Botach.com | Law Enforcement, Military & Public Safety Gear | FREE Shipping". botach.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012.

- ^ Christian Thiel. "Review FM81 throwing knife (Glock)". Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Bayonets of France". worldbayonets.com.

- ^ a b "SG 2000 WC-F". www.eickhorn-solingen.de.

- ^ Olive, Ronaldo (12 September 2013). "Morre o projetista Nelmo Suzano". Plano Brazil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Infantry combat badge

Bibliography

- Alexander, Bevin R. (1986), Korea: The First War We Lost, New York, NY: Hippocrene Books, Inc, ISBN 978-0-87052-135-5

- Appleman, Roy (1989), Disaster in Korea: The Chinese Confront MacArthur, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University Military History Series, 11, ISBN 978-1-60344-128-5

- Appleman, Roy (1990), Escaping the Trap: The US Army X Corps in Northeast Korea, 1950, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University Military History Series, 14, ISBN 0-89096-395-9

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Marshall, S.L.A. (1988), Infantry Operations and Weapon Usage in Korea, London, UK: Greenhill Books, ISBN 0-947898-88-3

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10694-7.

- Roe, Patrick C. (2000), The Dragon Strikes, Novato, CA: Presidio, ISBN 0-89141-703-6

Further reading

- Hunting weapons, Howard L Blackmore, 2000, Dover Publications