John of the Cross

John of the Cross | |

|---|---|

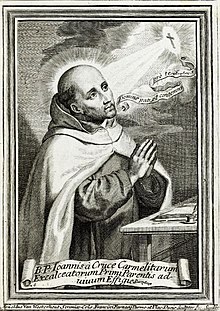

Portrait of Saint John of the Cross by Arnold van Westerhout | |

| Priest, Confessor and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | Juan de Yepes y Álvarez 24 June 1542[1] Fontiveros, Ávila, Crown of Castile |

| Died | 14 December 1591 (age 49) Úbeda, Kingdom of Jaén, Crown of Castile |

| Venerated in | |

| Beatified | 25 January 1675, Rome, Papal States by Pope Clement X |

| Canonized | 27 December 1726, Rome, Papal States by Pope Benedict XIII |

| Major shrine | Tomb of Saint John of the Cross, Segovia, Spain |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Carmelite habit, cross, crucifix, book, and a quill |

| Patronage | |

| Influences | Likely Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Guillaume Durand, Teresa of Ávila. Possibly Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, John of Ruysbroeck, Henry Suso, Johannes Tauler. |

John of the Cross, OCD (Template:Lang-es; Template:Lang-la; born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez; 24 June 1542 – 14 December 1591), venerated as Saint John of the Cross, was a Spanish Catholic priest, mystic, and a Carmelite friar of converso origin. He is a major figure of the Counter-Reformation in Spain, and he is one of the thirty-seven Doctors of the Church.

John of the Cross is known gratefully for his writings. He was mentored by and corresponded with the older Carmelite, Teresa of Ávila. Both his poetry and his studies on the development of the soul are considered the summit of mystical Spanish literature and among the greatest works of all Spanish literature. He was canonized by Pope Benedict XIII in 1726. In 1926 he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI, and is commonly known as the "Mystical Doctor".

Life

Early life and education

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez at Fontiveros, Old Castile into a converso family (descendants of Jewish converts to Catholicism) in Fontiveros, near Ávila, a town of around 2,000 people.[5][6][7] His father, Gonzalo, was an accountant to richer relatives who were silk merchants. In 1529 Gonzalo married John's mother, Catalina, who was an orphan of a lower class; he was rejected by his family and forced to work with his wife as a weaver.[8] John's father died in 1545, while John was still only around three years old.[9] Two years later, John's older brother, Luis, died, probably as a result of malnourishment due to the poverty to which the family had been reduced. As a result, John's mother Catalina took John and his surviving brother Francisco, first to Arévalo, in 1548 and then in 1551 to Medina del Campo, where she was able to find work.[10][11]

In Medina, John entered a school for 160[12] poor children, mostly orphans, to receive a basic education, mainly in Christian doctrine. They were given some food, clothing and lodging. While studying there, he was chosen to serve as an altar boy at a nearby monastery of Augustinian nuns.[10] Growing up, John worked at a hospital and studied the humanities at a Jesuit school from 1559 to 1563. The Society of Jesus was at that time a new organisation, having been founded only a few years earlier by the Spaniard St. Ignatius of Loyola. In 1563 he entered the Carmelite Order, adopting the name John of St. Matthias.[13][10]

The following year, in 1564 he made his First Profession as a Carmelite and travelled to Salamanca University, where he studied theology and philosophy.[14] There he met Fray Luis de León, who taught biblical studies (Exegesis, Hebrew and Aramaic) at the university.

Joining the Reform of Teresa of Ávila

John was ordained as a priest in 1567. He subsequently thought about joining the strict Carthusian Order, which appealed to him because of its practice of solitary and silent contemplation. His journey from Salamanca to Medina del Campo, probably in September 1567 became pivotal.[15] In Medina he met the influential Carmelite nun, Teresa of Ávila (in religion, Teresa of Jesus). She was staying in Medina to found the second of her new convents.[16] She immediately talked to him about her reformation projects for the Order: she was seeking to restore the purity of the Carmelite Order by reverting to the observance of its "Primitive Rule" of 1209, which had been relaxed by Pope Eugene IV in 1432.[citation needed]

Under the Rule, much of the day and night were to be divided between the recitation of the Liturgy of the Hours, study and devotional reading, the celebration of Mass and periods of solitude. In the case of friars, time was to be spent evangelizing the population around the monastery.[17] There was to be total abstinence from meat and a lengthy period of fasting from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (14 September) until Easter. There were to be long periods of silence, especially between Compline and Prime. More simple, that is coarser, shorter habits were to be adopted.[18] There was also an injunction against wearing covered shoes (also previously mitigated in 1432). That particular observance distinguished the "discalced", i.e., barefoot followers of Teresa from traditional Carmelites, and they would be formally recognized as the separate Order of Discalced Carmelites in 1580.

Teresa asked John to delay his entry into the Carthusian order and to follow her. Having spent a final year studying in Salamanca, in August 1568 John travelled with Teresa from Medina to Valladolid, where Teresa intended to found another convent. After a spell at Teresa's side in Valladolid, learning more about the new form of Carmelite life, in October 1568, John left Valladolid, accompanied by Friar Antonio de Jesús de Heredia, to found a new monastery for Carmelite friars, the first to follow Teresa's principles. They were given the use of a derelict house at Duruelo, which had been donated to Teresa. On 28 November 1568, the monastery was established, and on that same day, John changed his name to "John of the Cross".[19]

Soon after, in June 1570, the friars found the house at Duruelo was too small, and so moved to the nearby town of Mancera de Abajo, midway between Ávila and Salamanca. John moved from the first community to set up a new community at Pastrana in October 1570, and then a further community at Alcalá de Henares, as a house for the academic training of the friars. In 1572 he arrived in Ávila, at Teresa's invitation. She had been appointed prioress of the Convent of the Incarnation there in 1571.[20] John became the spiritual director and confessor of Teresa and the other 130 nuns there, as well as for a wide range of laypeople in the city.[10] In 1574, John accompanied Teresa for the foundation of a new religious community in Segovia, returning to Ávila after staying there a week. Aside from the one trip, John seems to have remained in Ávila between 1572 and 1577.[21]

At some time between 1574 and 1577, while praying in a loft overlooking the sanctuary in the Monastery of the Incarnation in Ávila, John had a vision of the crucified Christ, which led him to create his drawing of Christ "from above". In 1641, this drawing was placed in a small monstrance and kept in Ávila. This same drawing inspired the artist Salvador Dalí's 1951 work Christ of Saint John of the Cross.[22]

The height of Carmelite tensions

The years 1575–77 saw a great increase in tensions among Spanish Carmelite friars over the reforms of Teresa and John. Since 1566 the reforms had been overseen by Canonical Visitors from the Dominican Order, with one appointed to Castile and a second to Andalusia. The Visitors had substantial powers: they could move members of religious communities from one house to another or from one province to the next. They could assist religious superiors in the discharge of their office, and could delegate superiors between the Dominican or Carmelite orders. In Castile, the Visitor was Pedro Fernández, who prudently balanced the interests of the Discalced Carmelites with those of the nuns and friars who did not desire reform.[23]

In Andalusia to the south, the Visitor was Francisco Vargas, and tensions rose due to his clear preference for the Discalced friars. Vargas asked them to make foundations in various cities, in contradiction to the express orders from the Carmelite Prior General to curb expansion in Andalusia. As a result, a General Chapter of the Carmelite Order was convened at Piacenza in Italy in May 1576, out of concern that events in Spain were getting out of hand. It concluded by ordering the total suppression of the Discalced houses.[24]

That measure was not immediately enforced. King Philip II of Spain was supportive of Teresa's reforms, and so was not immediately willing to grant the necessary permission to enforce the ordinance. The Discalced friars also found support from the papal nuncio to Spain, Nicolò Ormaneto, Bishop of Padua, who still had ultimate power to visit and reform religious orders. When asked by the Discalced friars to intervene, Nuncio Ormaneto replaced Vargas as Visitor of the Carmelites in Andalusia with Jerónimo Gracián, a priest from the University of Alcalá, who was in fact a Discalced Carmelite friar himself.[10] The nuncio's protection helped John avoid problems for a time. In January 1576, John was detained in Medina del Campo by traditional Carmelite friars, but through the nuncio's intervention, he was soon released.[10] When Ormaneto died on 18 June 1577, John was left without protection, and the friars opposing his reforms regained the upper hand.[citation needed]

Foundations, imprisonment, torture and death

On the night of 2 December 1577, a group of Carmelites opposed to reform broke into John's dwelling in Ávila and took him prisoner. John had received an order from superiors, opposed to reform, to leave Ávila and return to his original house. John had refused on the basis that his reform work had been approved by the papal nuncio to Spain, a higher authority than these superiors.[25] The Carmelites therefore took John captive. John was taken from Ávila to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, at that time the order's leading monastery in Castile, with a community of 40 friars.[26][27]

John was brought before a court of friars, accused of disobeying the ordinances of Piacenza. Despite his argument that he had not disobeyed the ordinances, he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was jailed in a monastery where he was kept under a brutal regime that included public lashings before the community at least weekly, and severe isolation in a tiny stifling cell measuring barely 10 feet by 6 feet. Except when rarely permitted an oil lamp, he had to stand on a bench to read his breviary by the light through the hole into the adjoining room. He had no change of clothing and a penitential diet of water, bread and scraps of salt fish.[28] During his imprisonment, he composed a great part of his most famous poem Spiritual Canticle, as well as a few shorter poems. The paper was passed to him by the friar who guarded his cell.[29] He managed to escape eight months later, on 15 August 1578, through a small window in a room adjoining his cell. (He had managed to pry open the hinges of the cell door earlier that day.)[citation needed]

After being nursed back to health, first by Teresa's nuns in Toledo, and then during six weeks at the Hospital of Santa Cruz, John continued with the reforms. In October 1578 he joined a meeting at Almodóvar del Campo of reform supporters, better known as the Discalced Carmelites.[30] There, in part as a result of the opposition faced from other Carmelites, they decided to request from the Pope their formal separation from the rest of the Carmelite order.[10]

At that meeting John was appointed superior of El Calvario, an isolated monastery of around thirty friars in the mountains about 6 miles away[31] from Beas in Andalusia. During that time he befriended the nun, Ana de Jesús, superior of the Discalced nuns at Beas, through his visits to the town every Saturday. While at El Calvario he composed the first version of his commentary on his poem, The Spiritual Canticle, possibly at the request of the nuns in Beas.[citation needed]

In 1579 he moved to Baeza, a town of around 50,000 people, to serve as rector of a new college, the Colegio de San Basilio, for Discalced friars in Andalusia. It opened on 13 June 1579. He remained in post until 1582, spending much of his time as a spiritual director to the friars and townspeople.[citation needed]

1580 was a significant year in the resolution of disputes between the Carmelites. On 22 June, Pope Gregory XIII signed a decree, entitled Pia Consideratione, which authorised the separation of the old (later "calced") and the newly reformed, "Discalced" Carmelites. The Dominican friar Juan Velázquez de las Cuevas was appointed to oversee the decision. At the first General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites, in Alcalá de Henares on 3 March 1581, John of the Cross was elected one of the "Definitors" of the community, and wrote a constitution for them. By the time of the Provincial Chapter at Alcalá in 1581, there were 22 houses, some 300 friars and 200 nuns among the Discalced Carmelites.[32]

In November 1581, John was sent by Teresa to help Ana de Jesús to found a convent in Granada. Arriving in January 1582, she set up a convent, while John stayed in the monastery of Los Mártires, near the Alhambra, becoming its prior in March 1582.[33] While there, he learned of Teresa's death in October of that year.[citation needed]

In February 1585, John travelled to Málaga where he established a convent for Discalced nuns. In May 1585, at the General Chapter of the Discalced Carmelites in Lisbon, John was elected Vicar Provincial of Andalusia, a post which required him to travel frequently, making annual visitations to the houses of friars and nuns in Andalusia. During this time he founded seven new monasteries in the region, and is estimated to have travelled around 25,000 km.[34]

In June 1588, he was elected third Councillor to the Vicar General for the Discalced Carmelites, Father Nicolas Doria. To fulfill this role, he had to return to Segovia in Castile, where he also took on the role of prior of the monastery. After disagreeing in 1590–1 with some of Doria's remodelling of the leadership of the Discalced Carmelite Order, John was removed from his post in Segovia, and sent by Doria in June 1591 to an isolated monastery in Andalusia called La Peñuela. There he fell ill, and travelled to the monastery at Úbeda for treatment. His condition worsened, however, and he died there, of erysipelas on 14 December 1591.[10]

Veneration

The morning after John's death huge numbers of townspeople in Úbeda entered the monastery to view his body; in the crush, many were able to take home bits of his habit. He was initially buried at Úbeda, but, at the request of the monastery in Segovia, his body was secretly moved there in 1593. The people of Úbeda, however, unhappy at this change, sent a representative to petition the pope to move the body back to its original resting place. Pope Clement VIII, impressed by the petition, issued a Brief on 15 October 1596 ordering the return of the body to Úbeda. Eventually, in a compromise, the superiors of the Discalced Carmelites decided that the monastery at Úbeda would receive one leg and one arm of the corpse from Segovia (the monastery at Úbeda had already kept one leg in 1593, and the other arm had been removed as the corpse passed through Madrid in 1593, to form a relic there). A hand and a leg remain visible in a reliquary at the Oratory of San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda, a monastery built in 1627 though connected to the original Discalced monastery in the town founded in 1587.[35]

The head and torso were retained by the monastery at Segovia. They were venerated until 1647, when on orders from Rome designed to prevent the veneration of remains without official approval, the remains were buried in the ground. In the 1930s they were disinterred, and are now sited in a side chapel in a marble case above a special altar.[35]

Proceedings to beatify John began between 1614 and 1616. He was eventually beatified in 1675 by Pope Clement X, and was canonized by Benedict XIII in 1726. When his feast day was added to the General Roman Calendar in 1738, it was assigned to 24 November, since his date of death was impeded by the then-existing octave of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.[36] This obstacle was removed in 1955 and in 1969 Pope Paul VI moved it to the dies natalis (birthday to heaven) of John, 14 December.[37] The Church of England the Episcopal Church honor him on the same date.[38][2] In 1926, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI after the definitive consultation of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange O.P., professor of philosophy and theology at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum in Rome.[39]

Literary works

John of the Cross is considered one of the foremost poets in Spanish. Although his complete poems add up to fewer than 2500 verses, two of them, the Spiritual Canticle and the Dark Night of the Soul, are widely considered masterpieces of Spanish poetry, both for their formal style and their rich symbolism and imagery. His theological works often consist of commentaries on the poems. All the works were written between 1578 and his death in 1591.[citation needed]

The Spiritual Canticle is an eclogue in which the bride, representing the soul, searches for the bridegroom, representing Jesus Christ, and is anxious at having lost him. Both are filled with joy upon reuniting. It can be seen as a free-form Spanish version of the Song of Songs at a time when vernacular translations of the Bible were forbidden. The first 31 stanzas of the poem were composed in 1578 while John was imprisoned in Toledo. After his escape it was read by the nuns at Beas, who made copies of the stanzas. Over the following years, John added further lines. Today, two versions exist: one with 39 stanzas and one with 40 with some of the stanzas ordered differently. The first redaction of the commentary on the poem was written in 1584, at the request of Madre Ana de Jesús, when she was prioress of the Discalced Carmelite nuns in Granada. A second edition, which contains more detail, was written in 1585–6.[10]

The Dark Night, from which the phrase Dark Night of the Soul takes its name, narrates the journey of the soul from its bodily home to union with God. It happens during the "dark", which represents the hardships and difficulties met in detachment from the world and reaching the light of the union with the Creator. There are several steps during the state of darkness, which are described in successive stanzas. The main idea behind the poem is the painful experience required to attain spiritual maturity and union with God. The poem was likely written in 1578 or 1579. In 1584–5, John wrote a commentary on the first two stanzas and on the first line of the third stanza.[10]

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is a more systematic study of the ascetical endeavour of a soul seeking perfect union with God and the mystical events encountered along the way. Although it begins as a commentary on The Dark Night, after the first two stanzas of the poem, it rapidly diverts into a full treatise. It was composed some time between 1581 and 1585.[41]

A four-stanza work, Living Flame of Love, describes a greater intimacy, as the soul responds to God's love. It was written in a first version at Granada between 1585 and 1586, apparently in two weeks, and in a mostly identical second version at La Peñuela in 1591.[42]

These, together with his Dichos de Luz y Amor or "Sayings of Light and Love" along with Teresa's own writings, are the most important mystical works in Spanish, and have deeply influenced later spiritual writers across the world. They include: T. S. Eliot, Thérèse de Lisieux, Edith Stein (Teresa Benedicta of the Cross) and Thomas Merton. John is said to have also influenced philosophers (Jacques Maritain), theologians (Hans Urs von Balthasar), pacifists (Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan and Philip Berrigan) and artists (Salvador Dalí). Pope John Paul II wrote his theological dissertation on the mystical theology of John of the Cross.[citation needed]

Editions of his works

His writings were first published in 1618 by Diego de Salablanca. The numerical divisions in the work, still used by modern editions of the text, were introduced by Salablanca (they were not in John's original writings) to help make the work more manageable for the reader.[10] This edition does not contain the Spiritual Canticle however, and also omits or adapts certain passages, perhaps for fear of falling foul of the Inquisition.[43]

The Spiritual Canticle was first included in the 1630 edition, produced by Fray Jeronimo de San José, at Madrid. This edition was largely followed by later editors, although editions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries gradually included a few more poems and letters.[44]

The first French edition was published in Paris in 1622,[45] and the first Castilian edition in 1627 in Brussels.[46]

A critical edition of St John of the Cross's work in English was published by E. Allison Peers in 1935.[47]

Intellectual influences

The influences on John's writing are subject to an ongoing debate. It is widely acknowledged that at Salamanca university there would have existed a range of intellectual positions. In John's time they included the influences of Thomas Aquinas, of Scotus and of Durandus.[48] It is often assumed that John would have absorbed the thought of Aquinas, to explain the scholastic framework of his writings.[citation needed]

However, the belief that John was taught at both the Carmelite College of San Andrès and at the University of Salamanca has been challenged.[49] Bezares calls into question whether John even studied theology at the University of Salamanca. The philosophy courses John probably took in logic, natural and moral philosophy, can be reconstructed, but Bezares argues that John in fact abandoned his studies at Salamanca in 1568 to join Teresa, rather than graduating.[50] In the first biography of John, published in 1628, it is claimed, on the basis of information from John's fellow students, that he in 1567 made a special study of mystical writers, in particular of Pseudo-Dionysius and Pope Gregory I.[51][52] There is little consensus from John's early years or potential influences.[citation needed]

Scripture

John was influenced heavily by the Bible. Scriptural images are common in both his poems and prose. In total, there are 1,583 explicit and 115 implicit quotations from the Bible in his works.[53] The influence of the Song of Songs on John's Spiritual Canticle has often been noted, both in terms of the structure of the poem, with its dialogue between two lovers, the account of their difficulties in meeting each other and the "offstage chorus" that comments on the action, and also in terms of the imagery for example, of pomegranates, wine cellar, turtle dove and lilies, which echoes that of the Song of Songs.[53]

In addition, John shows at occasional points the influence of the Divine Office. This demonstrates how John, steeped in the language and rituals of the Church, drew at times on the phrases and language here.[54]

Pseudo-Dionysius

It has rarely been disputed that the overall structure of John's mystical theology, and his language of the union of the soul with God, is influenced by the pseudo-Dionysian tradition.[55] However, it has not been clear whether John might have had direct access to the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius, or whether this influence may have been mediated through various later authors.[citation needed]

Medieval mystics

It is widely acknowledged that John may have been influenced by the writings of other medieval mystics, though there is debate about the exact thought which may have influenced him, and about how he might have been exposed to their ideas.[citation needed]

The possibility of influence by the so-called "Rhineland mystics" such as Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Henry Suso and John of Ruysbroeck has also been mooted by many authors.[56]

Secular Spanish poetry

A strong argument can also be made for contemporary Spanish literary influences on John. This case was first made in detail by Dámaso Alonso, who believed that as well as drawing from scripture, John was transforming non-religious, profane themes, derived from popular songs (romanceros) into religious poetry.[57]

Islamic influence

A controversial theory on the origins of John's mystical imagery is that he may have been influenced by Islamic sources. This was first proposed in detail by Miguel Asín Palacios and has been most recently put forward by the Puerto Rican scholar Luce López-Baralt.[58] Arguing that John was influenced by Islamic sources on the peninsula, she traces Islamic antecedents of the images of the "dark night", the "solitary bird" of the Spiritual Canticle, wine and mystical intoxication (the Spiritual Canticle), lamps of fire (the Living Flame). However, Peter Tyler concludes, there "are sufficient Christian medieval antecedents for many of the metaphors John employs to suggest we should look for Christian sources rather than Muslim sources".[59] As José Nieto indicates, in trying to locate a link between Spanish Christian mysticism and Islamic mysticism, it might make more sense to refer to the common Neo-Platonic tradition and mystical experiences of both, rather than seek direct influence.[60]

Books

- John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul, London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-005-5

- John of the Cross, Ascent of Mount Carmel, London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-009-3

- John of the Cross, Spiritual Canticle of the Soul and the Bridegroom Christ, London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-014-7

- The Dark Night: A Masterpiece in the Literature of Mysticism (Translated and Edited by E. Allison Peers), Doubleday, 1959. ISBN 978-0-385-02930-8

- The Poems of Saint John of the Cross (English Versions and Introduction by Willis Barnstone), Indiana University Press, 1968, revised 2nd ed. New Directions, 1972. ISBN 0-8112-0449-9

- The Dark Night, St. John of the Cross (Translated by Mirabai Starr), Riverhead Books, New York, 2002, ISBN 1-57322-974-1

- Poems of St John of The Cross (Translated and Introduction by Kathleen Jones), Burns and Oates, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK, 1993, ISBN 0-86012-210-7

- The Collected Works of St John of the Cross (Eds. K. Kavanaugh and O. Rodriguez), Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington DC, revised edition, 1991, ISBN 0-935216-14-6

- "St. John of the Cross: His Prophetic Mysticism in Sixteenth-Century Spain" by Prof Cristobal Serran-Pagan

See also

- A lo divino

- Book of the First Monks

- Byzantine Discalced Carmelites

- Calendar of saints (Church of England)

- Carmelite Rule of St. Albert

- Christian meditation

- Constitutions of the Carmelite Order

- List of Catholic saints

- Miguel Asín Palacios

- Saint John of the Cross, patron saint archive

- Saint Raphael Kalinowski, the first friar to be canonized (in 1991 by Pope John Paul II) in the Order of Discalced Carmelites since Saint John of the Cross

- Spanish Renaissance literature

- Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites

- The world, the flesh, and the devil

References

- ^ "St. John of the Cross". Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ a b Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org.

- ^ In 1952, the Spanish National Ministry for Education named him Patron Saint of Spanish poets. The same ministry repeatedly authorized and approved the inclusion of John's writings among the canon of Spanish writers.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jose Vincente (1991). God Speaks in the Night. The Life, Times, and Teaching of St. John of the Cross'. Washington, DC: ICS Publications. p. 3.

- ^ Thompson, C.P., St. John of the Cross: Songs in the Night, London: SPCK, 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Roth, Norman. Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain, Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, pp. 157, 369

- ^ Tillyer, Desmond. Union with God: The Teaching of St John of the Cross, London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1984, p. 4

- ^ Gerald Brenan, St John of the Cross: His Life and Poetry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kavanaugh, Kieran (1991). "General Introduction: Biographical Sketch". In Kieran Kavanaugh (ed.). The Collected Works of St John of the Cross. Washington: ICS Publications. pp. 9–27. ISBN 0-935216-14-6.

- ^ Matthew, Iain (1995). The Impact of God, Soundings from St John of the Cross. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 3. ISBN 0-340-61257-6.

- ^ Thompson, p.31.

- ^ Kavanaugh (1991) names the date as 24 February. However, E. Allison Peers (1943), p. 13, points out that although the Feast Day of St. Matthias is often assumed to be the date, Father Silverio proposes a date in August or September for his postulancy.

- ^ He entered Salamanca University probably between 21 May not fall October. See E. Allison Peers, Spirit of Flame: A Study of St John of the Cross (London: SCM Press, 1943), p. 13

- ^ E. Allison Peers (1943, p. 16) suggests that the journey was to visit a nearby Carthusian monastery; Richard P. Hardy, The Life of St John of the Cross: Search for Nothing (London: DLT, 1982), p. 24, argues that the reason was for John to say his first mass

- ^ E. Allison Peers, Spirit of Flame: A Study of St John of the Cross (London: SCM Press, 1943), p. 16

- ^ Tillyer, p.8.

- ^ Hardy, Richard P., The Life of St John of the Cross: Search for Nothing (London: DLT, 1982), p. 27

- ^ The monastery may have contained three men, according to E. Allison Peers (1943), p. 27, or five, according to Richard P. Hardy, The Life of St John of the Cross: Search for Nothing (London: DLT, 1982), p. 35

- ^ The month generally given is May. E. Allison Peers, Complete Works Vol. I (1943, xxvi), agreeing with P. Silverio, thinks it must have been substantially later than this, though certainly before 27 September.

- ^ Hardy, p.56.

- ^ "Discover the crucifix drawn by St. John of the Cross after a mystical vision". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ He is possibly the same Pedro Fernández who became the Bishop of Ávila in 1581. He who appointed Teresa as prioress in Ávila in 1571, while also maintaining good relations with the Carmelite Prior Provincial of Castile.

- ^ Kavanaugh (1991) states that this was all the Discalced houses founded in Andalusia. E. Allison Peers, Complete Works, Vol. I, p. xxvii (1943) states that this was all the Discalced monasteries but two.

- ^ Bennedict Zimmermann. "Ascent of Mt. Carmel, introductory essay THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYSTICISM IN THE CARMELITE ORDER". Thomas Baker and Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 December 2009. |pages = 10,11

- ^ C. P. Thompson, St. John of the Cross: Songs in the Night (London: SPCK, 2002), p. 48. Thompson points out that many earlier biographers have stated the number of friars at Toledo to be 80, but this is simply taken from Crisogono's Spanish biography. Alain Cugno (1982) gives the number of friars as 800 — which Thompson assumes this must be a misprint. However, as Thompson details, the actual number of friars has been reconstructed from comparing various extant documents that in 1576, 42 friars belonged to the house, with only about 23 of them resident, the remainder being absent for various reasons. This is done by J. Carlos Vuzeute Mendoza, 'La prisión de San Juan de la Cruz: El convent del Carmen de Toledo en 1577 y 1578', A. García Simón, ed, Actas del congreso internacional sanjuanista, 3 vols. (Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León, 1993) II, pp. 427–436

- ^ Peter Tyler, St John of the Cross (New York: Continuum, 2000), p. 28. The reference to the El Greco painting is also taken from here. The priory no longer exists, having been destroyed in 1936 — it is now the Toledo Municipal car park.

- ^ Tillyer, p.10.

- ^ Dark night of the soul. Translation by Mirabai Starr. ISBN 1-57322-974-1 p. 8.

- ^ Peter Tyler, St John of the Cross (New York: Continuum, 2000), p. 33. The Hospital still exists, and is today a municipal art gallery in Toledo.

- ^ Thompson, p.117.

- ^ Thompson, p.119.

- ^ Hardy, p.90.

- ^ C. P. Thompson, St. John of the Cross: Songs in the Night, London: SPCK, 2002, p. 122. This would have been largely by foot or by mule, given the strict rules which governed the way in which Discalced friars were permitted to travel.

- ^ a b Richard P Hardy, The Life of St John of the Cross: Search for Nothing, (London: DLT, 1982), pp113-130

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 110

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 146

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ "Garrigou-Lagrange . Il tomista d'assalto". www.avvenire.it. 15 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Eric Truman Dicken, The Crucible of Love, (1963), pp. 238–242, points out that this image is neither a true representation of John's thought, nor is it true to the image drawn by John himself of the 'Mount'. This latter image was first published in 1929, from a 1759 copy of the original (now lost) almost certainly drawn by John himself. It is the 1618 image, though, which was influential on later depictions of the 'Mount', such as in the 1748 Venice edition and 1858 Genoa editions of John's work.

- ^ Kavanaugh, The Collected Works of St John of the Cross, 34.

- ^ Kavanaugh, The Collected Works of St John of the Cross, 634.

- ^ John of the Cross, Saint (1991). The collected works of Saint John of the Cross. Kieran Kavanaugh, Otilio Rodriguez (Revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications. p. 33. ISBN 0-935216-15-4. OCLC 22909281.

- ^ The Complete Works of Saint John of the Cross. Translated and edited by E. Allison Peers, from the critical edition of Silverio de Santa Teresa. 3 vols. (Westminster, MD: Newman Press, 1943). Vol. I, pp. l–lxxvi

- ^ Hernández, Gloria Maité (2021). Savoring God : comparative theopoetics. New York, NY, United States of America. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-19-090739-6. OCLC 1240828756.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ John of the Cross, Saint (1991). The collected works of Saint John of the Cross. Kieran Kavanaugh, Otilio Rodriguez (Revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications. p. 33. ISBN 0-935216-15-4. OCLC 22909281.

- ^ Merchant, Hoshang (7 July 2016), "St John of the Cross: Poems of Roy Campbell", Secret Writings of Hoshang Merchant, Oxford University Press, pp. 23–29, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199465965.003.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-946596-5, retrieved 1 June 2022

- ^ Crisogono (1958), pp. 33–35

- ^ By L. Rodríguez-San Pedro Bezares, 'La Formación Universitaria de Juan de la Cruz', Actas del Congreso Internacional Sanjuanista (Valladolid, 1993)

- ^ Bezares, p19

- ^ The 1628 biography of John is by Quiroga. The information is from Crisogono (1958), p. 38

- ^ Eulogio Pacho (1969), pp. 56–59; Steven Payne, John of the Cross and the Cognitive Value of Mysticism: An Analysis of Sanjuanist Teaching and its Philosophical Implications for Contemporary Discussions of Mystical Experience (1990), p. 14, n. 7)

- ^ a b Tyler, Peter (2010). St John of the Cross. New York: Continuum., p. 116

- ^ This occurs in the Living Flame at 1.16 and 2.3. See John Sullivan, 'Night and Light: the Poet John of the Cross and the Exultet of the Easter Liturgy', Ephemerides Carmeliticae, 30:1 (1979), pp. 52–68.

- ^ John mentions Dionysius explicitly four times—S2.8.6; N2.5.3; CB14-15.16; Ll3-3.49. Luis Girón-Negrón, 'Dionysian thought in sixteenth-century Spanish mystical theology', Modern Theology, 24(4), (2008), p699

- ^ However, there is little precise agreement on which particular mystics may have been influential. Jean Orcibal, S Jean de la Croix et les mystiques Rheno-Flamands (Desclee-Brouwer, Presence du Carmel, no. 6); Crisogono (1929), I, 17, believed that John was influenced more by German mysticism, than perhaps by Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Augustine of Hippo, Bernard of Clairvaux, the School of Saint Victor and the Imitation.

- ^ Dámaso Alonso, La poesía de San Juan de la Cruz (Madrid, 1942)

- ^ Luce Lopez Baralt, Juan de la Cruz y el Islam (1990)

- ^ Peter Tyler, St John of the Cross (2010), pp. 138–142

- ^ José Nieto, Mystic, Rebel, Saint: A Study of St. John of the Cross (Geneva, 1979)

Sources

- Hardy, Richard P., The Life of St John of the Cross: Search for Nothing, London: DLT, 1982

- Thompson, C.P., St. John of the Cross: Songs in the Night, London: SPCK, 2002

- Tillyer, Desmond. Union with God: The Teaching of St John of the Cross, London & Oxford: Mowbray, 1984

Further reading

- Howells, E. "Spanish Mysticism and Religious Renewal: Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Ávila, and John of the Cross (16th Century, Spain)", in Julia A. Lamm, ed., Blackwell Companion to Christian Mysticism, (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012)

- Kavanaugh, K. John of the Cross: doctor of light and love (2000)

- Matthew, Iain. The Impact of God, Soundings from St John of the Cross (Hodder & Stoughton, 1995)

- Payne, Stephen. John of the Cross and the Cognitive Value of Mysticism (1990)

- Stein, Edith, The Science of the Cross (translated by Sister Josephine Koeppel, O.C.D. The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Vol. 6, ICS Publications, 2011)

- Williams, Rowan. The wound of knowledge: Christian spirituality from the New Testament to St. John of the Cross (1990)

- Wojtyła, K. Faith According to St. John of the Cross (1981)

- "St. John of the Cross: His Prophetic Mysticism in Sixteenth-Century Spain" by Prof Cristobal Serran-Pagan

External links

- John of the Cross on Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Metaphysics of Mysticism: The Mystical Philosophy of Saint John of the Cross Biography of Saint John of the Cross

- Works by Saint John of the Cross at Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- Works by or about John of the Cross at the Internet Archive

- Works by John of the Cross at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas Merton on Saint John of the Cross

- Lectio divina and Saint John of the Cross

- The Life and Miracles of St. John of the Cross, Doctor and Confessor of the Church

- Verse-translation of The Dark Night of the Soul at Poems Found in Translation

- 1542 births

- 1591 deaths

- Burials in the Community of Castile and León

- 16th-century Christian saints

- 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic priests

- 16th-century Christian mystics

- Baroque writers

- Carmelite mystics

- Carmelite saints

- Carmelite spirituality

- Catholic spirituality

- Counter-Reformation

- Deaths from streptococcus infection

- Discalced Carmelites

- Doctors of the Church

- Founders of Catholic religious communities

- Incorrupt saints

- People from the Province of Ávila

- Roman Catholic mystics

- Spanish Catholic poets

- Spanish escapees

- Spanish hermits

- Spanish people of Jewish descent

- Spanish Roman Catholic saints

- 16th-century Spanish Roman Catholic theologians

- Spanish spiritual writers

- University of Salamanca alumni

- Venerated Carmelites

- Spanish Christian mystics

- Anglican saints

- Venerated Catholics

- Canonizations by Pope Benedict XIII

- Beatifications by Pope Clement X