Ancient Greek funeral and burial practices

Ancient Greek funerary practices are attested widely in literature, the archaeological record, and in ancient Greek art. Finds associated with burials are an important source for ancient Greek culture, though Greek funerals are not as well documented as those of the ancient Romans.[1]

Mycenaean Period

The Mycenaeans practiced a burial of the dead, and did so consistently.[2] The body of the deceased was prepared to lie in state, followed by a procession to the resting place, a single grave or a family tomb. These processions were usually done by family or friends of the deceased. Processions and ritual laments are depicted on burial chests (larnakes) from Tanagra. Grave goods such as jewelry, weapons, and vessels were arranged around the body on the floor of the tomb. Graveside rituals included libations and a meal, since food and broken cups are also found at tombs. A tomb at Marathon contained the remains of horses that may have been sacrificed at the site after drawing the funeral cart there. The Mycenaeans seem to have practiced secondary burial, when the deceased and associated grave goods were rearranged in the tomb to make room for new burials. Until about 1100 BC, group burials in chamber tombs predominated among Bronze Age Greeks.[3]

Mycenaean cemeteries were located near population centers, with single graves for people of modest means and chamber tombs for elite families. The tholos is characteristic of Mycenaean elite tomb construction. The royal burials uncovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1874 remain the most famous of the Mycenaean tombs. With grave goods indicating they were in use from about 1550 to 1500 BC, these were enclosed by walls almost two and a half centuries later—an indication that these ancestral dead continued to be honored. An exemplary stele depicting a man driving a chariot suggests the esteem in which physical prowess was held in this culture.

Later Greeks thought of the Mycenaean period as an age of heroes, as represented in the Homeric epics. Greek hero cult centered on tombs.

Archaic and Classical Greece

After 1100 BC, Greeks began to bury their dead in individual graves rather than group tombs. Athens, however, was a major exception; the Athenians normally cremated their dead and placed their ashes in an urn.[4] During the early Archaic period, Greek cemeteries became larger, but grave goods decreased. This greater simplicity in burial coincided with the rise of democracy and the egalitarian military of the hoplite phalanx, and became pronounced during the early Classical period (5th century BC).[4] During the 4th century, the decline of democracy and the return of aristocratic dominance was accompanied by more magnificent tombs that announced the occupants' status—most notably, the vaulted tombs of the Macedonians, with painted walls and rich grave goods, the best example of which is the tomb at Vergina thought to belong to Philip II of Macedon.[4]

Funeral rites

A dying person might prepare by arranging future care for the children, praying, sending all valuables to close family, and assembling family members for a farewell.[5] Many funerary steles show the deceased, usually sitting or sometimes standing, clasping the hand of a standing survivor, often the spouse. When a third onlooker is present, the figure may be their adult child.

Women played a major role in funeral rites. They were in charge of preparing the body, which was washed, anointed and adorned with a wreath. The mouth was sometimes sealed with a token or talisman, referred to as "Charon's obol" if a coin was used, and explained as payment for the ferryman of the dead to convey the soul from the world of the living to the world of the dead.[6] Initiates into mystery religions might be furnished with a gold tablet, sometimes placed on the lips or otherwise positioned with the body, that offered instructions for navigating the afterlife and addressing the rulers of the underworld, Hades and Persephone; the German term Totenpass, "passport for the dead," is sometimes used in modern scholarship for these.

Priest or priestess were not allowed to enter the house of the deceased or to take part in the funerary rites, as death was seen as a cause of spiritual impurity or pollution.[7] This is in line with the Greek idea that even the gods could be polluted by death, and hence anything related to the sacred had to be kept away from death and dead bodies. Hence, many inscriptions in Greek temples banned those who had recent contact with dead bodies.[8]

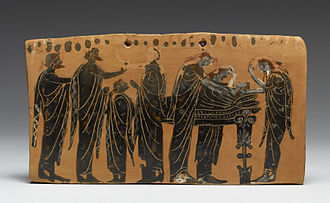

After the body was prepared, it was laid out for viewing on the second day. Kinswomen, wrapped in dark robes, stood round the bier, the chief mourner, either mother or wife, was at the head, and others behind.[9] This part of the funeral rites was called the prothesis. Women led the mourning by chanting dirges, tearing at their hair and clothing, and striking their torso, particularly their breasts.[6] The Prothesis may have previously been an outdoor ceremony, but a law later passed by Solon decreed that the ceremony take place indoors.[10] Before dawn on the third day, the funeral procession (ekphora) formed to carry the body to its resting place.[11]

At the time of the funeral, offerings were made to the deceased by only a relative and lover. The choai, or libation, and the haimacouria, or blood propitiation were two types of offerings. The choai dates back to Minoan times.[8] Since there is a complete absence of any references of animal sacrifices on Attic lêkythoi, this provides the grounds for inferring that the practice as conducted on behalf of ordinary dead was at least very rare. [8] The mourner first dedicated a lock of hair, along with choai, which were libations of honey, milk, water, wine, perfumes, and oils mixed in varying amounts. Choai were usually poured at the grave, either on to the steps supporting the stêlê, or possibly over the shaft.[8] A prayer then followed these libations. Then came the enagismata, which were offerings to the dead that included milk, honey, water, wine, celery, pelanon (a mixture of meal, honey, and oil), and kollyba (the first fruits of the crops and dried fresh fruits).[9] Once the burial was complete, the house and household objects were thoroughly cleansed with seawater and hyssop, and the women most closely related to the dead took part in the ritual washing in clean water. Afterwards, there was a funeral feast called the peridinin. The dead man was the host, and this feast was a sign of gratitude towards those who took part in burying him. The family would then be tasked with visiting the grave at set intervals up to a year to continue libations and rituals. After the first year, annual visits would be expected. During this year, families would have a laurel or other plant-based indicator that their family was unclean. Only after the first year would the family be fully re-accepted into society and considered free of pollution.

Scenes from funerary steles

-

Mother handing infant into a nurse's care (425–400 BC)

-

With horse (370s BC)

-

Farewell handshake (350–325 BC)

-

Presentation of wreaths (Bithynian, 150–100 BC)

-

Military theme (late 4th century BC)

-

Child holding doll and bird, with goose (310 BC)

-

Athenian shoemaker (430–420 BC)

-

Funerary Stela of Demokleides (circa 394 BC)

Commemoration and afterlife

Although the Greeks developed an elaborate mythology of the underworld, its topography and inhabitants, they and the Romans were unusual in lacking myths that explained how death and rituals for the dead came to exist. The ruler of the underworld was Hades, not the embodiment of death/personification of death, Thanatos, who was a relatively minor figure. Hades was not viewed the same way as the devil is in modern times, as he was a god of the underworld.[12]

Performing the correct rituals for the dead was essential, however, for assuring their successful passage into the afterlife, and unhappy revenants could be provoked by failures of the living to attend properly to either the rite of passage or continued maintenance through graveside libations and offerings, including hair clippings from the closest survivors. The dead were commemorated at certain times of the year, such as Genesia.[13] Exceptional individuals might continue to receive cult maintenance in perpetuity as heroes, but most individuals faded after a few generations into the collective dead, in some areas of Greece referred to as "thrice-ancestors" (tritopatores), who also had annual festivals devoted to them.[13]

See also

- Ancient Greek funerary vases

- Funeral oration (ancient Greece)

- Kerameikos, site of an extensive cemetery at Athens

- Lekythos, a type of vessel holding oils or liquids often used in connection with death rites

- Seikilos epitaph

- Sit tibi terra levis

References

- ^ Peter Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), vol. 1, p. 364.

- ^ Unless otherwise indicated, information in this section comes from Linda Maria Gigante, entry on "Funerary Art," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 1, p. 245.

- ^ Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," in p. 365.

- ^ a b c Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," p. 365.

- ^ Robert Garland, "Death in Greek Literature," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 1, p. 371.

- ^ a b Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," p. 363.

- ^ Garland, Robert (1998). Daily life of the ancient Greeks. Westport, Connecticut. ISBN 0-313-30383-5. OCLC 38157341.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Garland, Robert (2001). The Greek way of death. Ithaca, N.Y. ISBN 0-8014-8746-3. OCLC 47675022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Alexiou,"The Ritual Lament In Greek Tradition," pp. 6–7.

- ^ Johnston, "Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece," p. 40.

- ^ Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," p. 364.

- ^ Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," p. 367.

- ^ a b Toohey, "Death and Burial in the Ancient World," p. 368.