Rattanakosin Kingdom (1782–1932)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

| Rattanakosin Kingdom | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1782–1932 | |||

A red flag with a white Sudarshana Chakra of Vishnu which is used as the symbol of Chakri Dynasty. Adopted by King Rama I (Buddha Yodfa Chulalok). | |||

| Monarch(s) | Phutthayotfa Chulalok (King Rama I) Phutthaloetla Naphalai (King Rama II) Nangklao (King Rama III) Mongkut (King Rama IV) Chulalongkorn (King Rama V) Vajiravudh (King Rama VI) Prajadhipok (King Rama VII) | ||

Chronology

| |||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

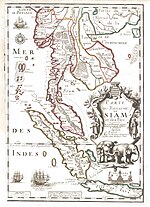

The Rattanakosin Kingdom (Template:Lang-th, pronounced [āːnāːt͡ɕàk ráttanákōːsǐn] ) is the fourth and present kingdom in the history of Thailand. It was founded in 1782 with the establishment of Rattanakosin as the capital city. This article covers the period until the Siamese revolution of 1932.

The maximum zone of influence of Rattanakosin included the vassal states of Cambodia, Laos, Shan States, and some Malay kingdoms. The kingdom was founded by Rama I of the Chakri. The first half of this period was characterized by the consolidation of the kingdom's power and was punctuated by periodic conflicts with Myanmar, Vietnam and Laos. The second period was one of engagements with the colonial powers of Britain and France in which Siam remained the only Southeast Asian state to maintain its independence.[1]

Internally the kingdom developed into a modern centralized nation state with borders defined by interactions with Western powers. Economic and social progress was made, marked by an increase in foreign trade, the abolition of slavery and the expansion of formal education to the emerging middle class. However, the failure to implement substantial political reforms culminated in the 1932 revolution and the abandonment of absolute monarchy in favor of a constitutional monarchy.

Background

In 1767, after dominating Southeast Asia for almost four centuries, Ayutthaya was brought down by invading Burmese armies.[2]

Despite its complete defeat and subsequent occupation by the Konbaung dynasty, Siam made a rapid recovery. The resistance to Myanmarese rule was led by a noble of Chinese descent, Taksin, a military leader. Initially based at Chanthaburi in the southeast, within a year, he had defeated the Myanmarese occupation army and reestablished a Siamese state with its capital at Thonburi on the west bank of the Chao Phraya, 20 km from the sea. In 1768 he was crowned as Taksin. He re-united the central Thai heartlands under his rule, and in 1769 he also occupied western Cambodia.[3]

He then marched south and reestablished Siamese rule over the Malay Peninsula as far as Penang and Terengganu. Having secured his base in Siam, Taksin attacked the Myanmarese in the north in 1774 and captured Chiang Mai in 1776, permanently uniting Siam and Lanna. Taksin's leading general in this campaign was Thong Duang, known by the title Chaophraya or Lord Chakri was himself a descendant of Mon people. In 1778 Chakri led a Siamese army which captured Vientiane, also Luang Phrabang, a northern Lao kingdom submitted, and eventually established Siamese domination over Laotian kingdoms.

Despite these successes, by 1779 Taksin was in political trouble at home. He seems to have developed a religious mania, alienating the powerful Buddhist monk-hood by claiming to be a sotapanna or divine figure. He was also in troubles with the court officials, Chinese merchants, and missionaries. The foreign observers began to speculate that he would soon be overthrown. In 1782 Taksin sent his armies under Chakri, the future Rama I of Rattanakosin, to invade Cambodia, but while they were away a rebellion broke out in the area around the capital. The rebels, who had popular support, offered the throne to General Chakri, the 'supreme general'. Chakri who was on war duty marched back from Cambodia and deposed Taksin, who was purportedly 'secretly executed' shortly after.

Chakri ruled under the name Ramathibodi (he was posthumously given the name Phutthayotfa Chulalok), but is now generally known as Rama I, first king of the later known Chakri dynasty. One of his first decisions was to move the capital across the river to the village of Bang Makok (meaning "place of olive plums"). The new capital was located on the island of Rattanakosin, protected from attack by the river to the west and by a series of canals to the north, east and south. Siam thus acquired both its current dynasty and its current capital.[4]

History

Foundation (1782–1809)

Rama I who was himself of Mon, Thai and Chinese descent[5][6] restored most of the social and political system of the Ayutthaya kingdom, promulgating new law codes, reinstating court ceremonies[7] and imposing discipline on the Buddhist monkhood. His government was carried out by six great ministries (Krom) headed by royal princes. Four of these administered particular territories: the Kalahom the south; the Mahatthai the north and east; the Phrakhlang the area immediately south of the capital; and the Krom Mueang, the area around Bangkok. The other two were the ministry of lands (Krom Na) and the ministry of the royal court (Krom Wang). The army was controlled by the King's deputy and brother, the Uparat.

The Myanmarese, seeing the disorder accompanying the overthrow of Taksin, invaded Siam again in 1785. Rama allowed them to occupy both the north and the south, but the Uparat, vice-king, his brother, led the Siamese army into western Siam and crushed the Myanmarese forces in a battle near Kanchanaburi. This was the last major Myanmarese invasion of Siam, although as late as 1802 Myanmarese forces had to be driven out of Lanna. In 1792 the Siamese occupied Luang Prabang and brought most of Laos under indirect Siamese rule. Cambodia was also effectively ruled by Siam. By the time of his death in 1809 Rama I had created a Siamese overlordship dominating an area considerably larger than modern Thailand.[8]

Invasion of Vietnam

In 1776 when Tây Sơn rebel forces captured Gia Dinh they executed the entire Nguyen royal family and much of the local population. Nguyễn Ánh, the only member of the Nguyễn family still alive, managed to escape across the river to Siam. While in exile Nguyễn Ánh wished to retake Gia Dinh and push the Tay-Son rebels out. He convinced the neutral King Phutthayotfa Chulalok of Siam to provide him with support troops and a small invasion force.

In mid-1784 Nguyễn Ánh, with 50,000 Siamese troops and 300 ships, moved through Cambodia, then East of Tonlé Sap and penetrated the recently annexed provinces of Annam. 20,000 Siamese troops reached Kien Giang and another 30,000 landed in Chap Lap, as the Siamese advanced towards Cần Thơ. Later that year the Siamese captured the former Cambodian province of Gia Dinh where, it was claimed, they committed atrocities against the population of Viet settlers.

Nguyễn Huệ anticipating a move from the Siamese, had secretly positioned his infantry along the Tiền river near present-day Mỹ Tho, and on some islands in the middle, facing other troops on the northern banks with naval reinforcements on both sides of the infantry positions.

On the morning of 19 January Nguyễn Huệ sent a small naval force, under a banner of truce, to lure the Siamese into his trap. After so many victories, the Siamese army and naval forces were confident of a surrender. So, they went to the parley, unaware of the trap. Nguyễn Huệ's troops dashed into the Siamese formation, slaughtered the unarmed emissaries and turned on the unprepared troops. The battle ended with a near annihilation of the Siamese force. All the ships of the Siamese navy were destroyed and only 1,000 of the original expedition survived to escape back across the river into Siam.

Wars with Myanmar

Soon King Bodawpaya of Myanmar started to pursue his ambitious campaigns to expand his dominions over Siam. The Burmese-Siamese War (1785–1786), also known in Siam as the "Nine Armies War" because the Myanmarese came in nine armies, thus broke out. The Myanmarese soldiers poured into Lanna and Northern Siam. Siamese forces, commanded by Kawila, Prince of Lampang, put up a brave fight and delayed the Myanmarese advance, all the while waiting for reinforcements from Bangkok. When Phitsanulok was captured, Anurak Devesh the Rear Palace, and Rama I himself led Siamese forces to the north. The Siamese relieved Lampang from the Myanmarese siege.

In the south, Bodawpaya was waiting at Chedi Sam Ong ready to attack. The Front Palace was ordered to lead his troops to the south and counter-attack the Myanmarese coming to Ranong through Nakhon Si Thammarat. He brought the Myanmarese to battle near Kanchanaburi. The Myanmarese also attacked Thalang (Phuket), where the governor had just died. His wife Chan, and her sister Mook, gathered the local people and successfully defended Thalang against the Myanmarese. Today, Chan and Mook are revered as heroines because of their opposition to the Myanmarese invasions. In their own lifetimes, Rama I bestowed on them the titles Thao Thep Kasattri and Thao Sri Sunthon.

The Myanmarese proceeded to capture Songkhla. Upon hearing the news, the governors of Phatthalung fled. However, a monk named Phra Maha encouraged the citizens of the area to take up arms against the Myanmarese, his campaign was also successful. Phra Maha was later raised to the nobility by Rama I.

As his armies were destroyed, Bodawpaya retreated. The next year, he attacked again, this time constituting his troops as a single army. With this force Bodawpaya passed through the Three Pagoda Pass and settled in Ta Din Dang (Three Pagoda Pass.) The Front Palace marched the Siamese forces to face Bodawpaya. The fighting was very short and Bodawpaya was quickly defeated. This short war was called the "Ta Din Dang campaign".

Economics, culture and religion

Chinese immigration increased during Rama I's reign, as he maintained Taksin's policy of allowing Chinese immigration to sustain the country's economy. The Chinese were found mainly in the trading and mercantile sector, and by the time his son and grandson came to the throne, European explorers noted that Bangkok was filled with Chinese junks of all sizes.[9]

Rama I moved the capital from Thonburi, which was founded by his predecessor Taksin, and built the new capital, Bangkok. During the first few years prior to the founding of the capital, he oversaw the construction of the palaces and the Chapel Royal. The Chapel Royal or Wat Phra Kaew, where the Emerald Buddha is enshrined, is on the grounds of his Grand Palace. With the completion of the new capital, Rama I held a ceremony naming the new capital.[10]

In 1804, Rama I began the compilation of the Three Seals Law, consisting of old Ayutthayan laws collected and organized.[11]: 9, 30 ) He also initiated a reform of government and the style of kingship.

Rama I was also noted for instituting major reforms in Buddhism as well as restoring moral discipline among the monks of the country, which had gradually eroded with the fall of Ayutthaya. Monks had already dabbled in superstitions when he first came to power, and Rama I implemented a law which required a monk who wished to travel to another principality for further education to present a certificate bearing his personal particulars, which would establish a monk bona fides and that he had been properly ordained. The king also repeatedly emphasized devotion to the Buddha, not to guardian spirits and past rulers, vestiges of ancient animist worship which persisted among Thais prior to his rule.[12]: 221–222

The king also appointed the first Supreme Patriarch of Thai Buddhism, whose responsibilities included ensuring that Rama I's laws were maintained within the Buddhist Sangha.[12]: 222 Rama I encouraged the translation of ancient Pali works and Buddhist texts lost in the chaos after the sacking of Ayutthaya by the Myanmarese in 1767. He also wrote a Thai version of the Ramayana epic called Ramakian.[12]: 221

Rama I renewed relations with the Vatican and the Jesuits. Missionaries who were expelled during Taksin's reign were invited back to Siam. Catholic missionary activities then continued in Siam. Reportedly the numbers of local Catholics increased steadily to thousands as their churches were protected, gaining freedom to propagate their beliefs again.[13]

Peace (1809–1824)

The reign of Rama I's son Phutthaloetla Naphalai (now known as King Rama II) was relatively uneventful. The Chakri family now controlled all branches of Siamese government — since Rama I had 42 children, his brother the Uparat had 43, and Rama II had 73, there was no shortage of royal princes to staff the bureaucracy, the army, the senior monk-hood, and the provincial governments. (Most of these were the children of concubines and thus not eligible to inherit the throne.) There was a confrontation with Vietnam, now becoming a major power in the region, over control of Cambodia in 1813, ending with the status quo ante restored. But during Rama II's reign Western influences again began to be felt in Siam.

In 1786 the British East India Company occupied Penang, and in 1819 they founded Singapore. Soon the British displaced the Dutch and Portuguese as the main Western economic and political influence in Siam. The British objected to the Siamese economic system, in which trading monopolies were held by royal princes and businesses were subject to arbitrary taxation. In 1821, the East India Company's Lord Hastings, then Governor-General of India, sent company agent John Crawfurd on a mission to negotiate a new trade agreement with Siam — the first sign of an issue which was to dominate 19th century Siamese politics.[14]

Art and literature

Rama II was a lover of the arts and in particular the literary arts. He was an accomplished poet and anyone with the ability to write a refined piece of poetry would gain the favor of the king. This led to his being dubbed the "poet king". Due to his patronage, the poet Sunthon Phu was able to raise his noble title from "phrai" to "khun" and later "phra". Sunthon – also known as the drunken writer – wrote numerous works, including the epic poem Phra Aphai Mani.

Rama II rewrote much of the great literature from the reign of Rama I in a modern style. He is credited with writing a popular version of the Thai folk tale Ramakien and wrote a number of dance dramas such as Sang Thong. The king was an accomplished musician, playing and composing for the fiddle and introducing new instrumental techniques. He was also a sculptor and is said to have sculpted the face of the Niramitr Buddha in Wat Arun. Because of his artistic achievements, Rama II's birthday is now celebrated as National Artists' Day (Wan Sinlapin Haeng Chat), held in honor of artists who have contributed to the cultural heritage of the kingdom.

Consolidation (1824–1851)

Rama II died in 1824 and was peacefully succeeded by his son Prince Jessadabondindra, who reigned as King Phra Nangklao, now known as Rama III. Rama II's younger son, Mongkut, was "encouraged" to become a monk, removing him from politics.

In 1825 the British sent another mission to Bangkok led by East India Company emissary Henry Burney. They had by now annexed southern Myanmar and were thus Siam's neighbors to the west, and they were also extending their control over Malaya. The king was reluctant to give in to British demands, but his advisors warned him that Siam would meet the same fate as Myanmar unless the British were accommodated. In 1826, therefore, Siam concluded its first commercial treaty with a Western power, the Burney Treaty. Under the treaty, Siam agreed to establish a uniform taxation system, to reduce taxes on foreign trade, and to abolish some royal monopolies. As a result, Siam's trade increased rapidly, many more foreigners settled in Bangkok, and Western cultural influences began to spread. The kingdom became wealthier and its army better armed.

A Lao rebellion led by Anouvong was defeated in 1827, following which Siam destroyed Vientiane, carried out massive forced population transfers from Laos to the more securely held area of Isan, and divided the Lao mueang into smaller units to prevent another uprising. In 1842–1845 Siam waged a successful war with Vietnam, which tightened Siamese rule over Cambodia. Rama III's most visible legacy in Bangkok is the Wat Pho temple complex, which he enlarged and endowed with new temples.

Rama III regarded his brother Mongkut, who was said to be very popular among the British, as his heir, although as a monk, Mongkut could not openly assume this role. He used his long sojourn as a monk to acquire a Western education from French and American missionaries and British merchants, one of the first Siamese to do so. He learned English and Latin, and studied science and mathematics. The missionaries no doubt hoped to convert him to Christianity, but he was a strict Buddhist and a Siamese nationalist. He intended using this Western knowledge to strengthen and modernize Siam when he came to the throne, which he did in 1851.

By the 1840s it was obvious that Siamese independence was in danger from the colonial powers: this was shown dramatically by the British First Opium War with China in 1839–1842. In 1850 the British and Americans sent missions to Bangkok demanding the end of all restrictions on trade, the establishment of a Western-style government and immunity for their citizens from Siamese law (extraterritoriality). Rama III's government refused these demands, leaving his successor with a dangerous situation. Rama III reportedly said on his deathbed: "[T]here will be no more wars with Myanmar and Vietnam. We will have them only with the West."[15]

Economically, from its foundation, Rattanakosin witnessed the growing role of Chinese merchants, a policy that started with King Taksin, himself the son of a Chinese merchant.[6] Beside merchants, Chinese farmers came to seek fortune in the new kingdom. Rattanakosin's rulers welcomed the Chinese economic stimulus. Some ethnic Chinese merchants became court officials. Chinese culture was accepted and promoted. Many Chinese works were translated by ethnic Chinese court dignitaries. Siam's relationship with the Chinese Empire was strong. Rama I claimed his blood-relation with Taksin, worrying that the Chinese court might reject his approval. The relationship was guaranteed by the tributary missions, continuing until the Rama IV's reign.

Enlightenment (1851–1868)

Mongkut came to the throne as Rama IV in 1851, determined to prevent Siam from falling under colonial domination by forcing modernization on his reluctant subjects. But although he was in theory an absolute monarch, his power was limited. Having been a monk for 27 years, he lacked a base among the powerful royal princes, and did not have a modern state apparatus to carry out his wishes. His first attempts at reform, to establish a modern system of administration and to improve the status of debt-slaves and women, were frustrated.

Rama IV came to welcome Western intrusion in Siam. The king himself and his entourages were actively pro-British. This became evident in 1855 when a mission led by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir John Bowring, arrived in Bangkok with demands for immediate changes, backed by the threat of force. The king readily agreed to demands for a new treaty, called the Bowring Treaty, which restricted import duties to three percent, abolished royal trade monopolies, and granted extraterritoriality to British subjects. Other Western powers soon demanded and got similar concessions.

The king came to believe that the real threat to Siam came from the French, not the British. The British were interested in commercial advantage, the French in building a colonial empire. They occupied Saigon in 1859, and 1867 established a protectorate over southern Vietnam and eastern Cambodia. Rama IV hoped that the British would defend Siam if he gave them the economic concessions they demanded. In the next reign this would prove to be an illusion, but it is true that the British saw Siam as a useful buffer state between British Burma and French Indochina.

Dhammayuttika Nikaya

The instrument of Mongkut's religious reformation was a new Buddhist order, the Dhammayuttika Nikaya. Dhammayuttika monks became a clerical vanguard of a movement promoting a new interpretation of Buddhism, one that sought to demythologize the religion.[16] By this religious reformation order, Wat Bowonniwet Vihara become the administrative center of the Thammayut order to the present day.[17]

Initially, the Thammayut order had been confined to two monasteries. During Mongkut's reign (1851-1868) the order spread into Laos and Cambodia.

-

Ordination Hall of Wat Bowonniwet Vihara.

-

Surrounding wall at Wat Bowonniwet Vihara

-

Tympanums of Phra Ubosot, Wat Bowonniwet Vihara.

Reformer (1868–1910)

Rama IV died in 1868, and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son Chulalongkorn, who reigned as Rama V and is now known as Rama the Great. Rama V was the first Siamese king to have a full Western education, having been taught by a British governess, Anna Leonowens – whose place in Siamese history has been fictionalized as The King and I. At first Rama V's reign was dominated by the conservative regent, Chaophraya Si Suriyawongse, but when the king came of age in 1873 he soon took control. He created a Privy Council and a Council of State, a formal court system and budget office. He announced that slavery would be gradually abolished and debt-bondage restricted.

At first the princes and conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger, Western-educated princes, resistance faded. He found powerful allies in his brothers Prince Chakkraphat, whom he made finance minister, Prince Damrong, who organized interior government and education, and his brother-in-law Prince Devrawongse, foreign minister for 38 years. In 1887 Devrawonge visited Europe to study governmental systems. On his recommendation the king established cabinet government, an audit office, and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganized and modernized.

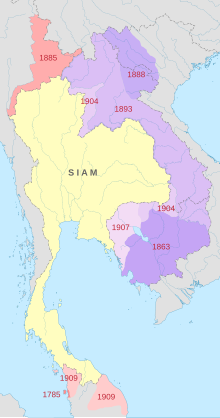

In 1893 French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the Mekong. The king appealed to the British, but the British minister told the king to settle on whatever terms he could get. The king had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of northeastern Myanmar to the British.

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1906–1907 they manufactured another crisis. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. The British interceded to prevent more French pressure on Siam, but their price, in 1909 was the acceptance of British sovereignty over of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu under Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. All of these "lost territories" were on the fringes of the Siamese sphere of influence and had never been securely under their control, but being compelled to abandon all claim to them was a substantial humiliation to both king and country. Historian David K. Wyatt describes Chulalongkorn as "broken in spirit and health" following the 1893 crisis. It became the basis for the country's name change: with the loss of these territories Great Siam was no more, the king now ruled only the core "Thai lands".

Meanwhile, reform continued unabated, transforming an absolute monarchy based on traditional relationships of power into a modern, centralized nation state. The process was increasingly under the control of Rama V's European-educated sons. Railways and telegraph lines united previously remote and semi-autonomous provinces. The currency was tied to the gold standard and a modern system of taxation replaced the arbitrary levies and corvee labor of the past. The biggest problem was the shortage of trained civil servants, and many foreigners had to be employed until new schools could be built and Siamese graduates produced. By 1910, when the king died, Siam had become a semi-modern country and continued to escape colonial rule.

From kingdom to modern nation (1910–1925)

One of Rama V's reforms was to introduce a Western-style law of royal succession, so in 1910 he was peacefully succeeded by his son Vajiravudh, who reigned as Rama VI. He had been educated at Sandhurst military academy and at Oxford, and was an anglicized Edwardian gentleman. Indeed, one of Siam's problems was the widening gap between the Westernized royal family and upper aristocracy and the rest of the country. It took another 20 years for Western education to permeate the bureaucracy and the army.

There had been some political reform under Rama V, but the king was still an absolute monarch, who acted as the head of the cabinet and staffed all the agencies of the state with his own relatives. The new king Vajiravudh, the son of Rama V, with his British education, knew that the rest of the "new" nation could not be excluded from government forever, but he had no faith in Western-style democracy. He applied his observations of the success of the British monarchy ruling India, appearing more in public and instituting more royal ceremonies. However Rama VI also carried on his father's modernization plan.

Bangkok became more and more the capital of the new nation of Siam. Rama VI's government began several nationwide development projects, despite financial hardship. New roads, bridges, railways, hospitals and schools mushroomed throughout the country with funds from Bangkok. Newly created "viceroys" were appointed to the newly restructured "Region", or Monthon (Circle), as king's agents supervising administrative affairs in the provinces.

The king established the Wild Tiger Corps, or Kong Suea Pa (กองเสือป่า), a paramilitary organization of Siamese of "good character" united to further the nation's cause. He also created a junior branch which continues today as the National Scout Organization of Thailand. The king spent much time on the development of the movements as he saw it as an opportunity to create a bond between himself and loyal citizens. It was also a way to single out and honor his favorites. At first the Wild Tigers were drawn from the king's personal entourage (it is likely that many joined to gain favor with Vajiravudh), but an enthusiasm among the population arose later.

Of the adult movement, a German observer wrote in September 1911: "This is a troop of volunteers in black uniform, drilled in a more or less military fashion, but without weapons. The British Scouts are apparently the paradigm for the Tiger Corps. In the whole country, at the most far-away places, units of this corps are being set up. One would hardly recognize the quiet and phlegmatic Siamese."

The paramilitary movement largely disappeared by 1927, but was revived and evolved into the Volunteer Defense Corps, also called the Village Scouts. (ลูกเสือบ้าน)[18]

Vajiravudh's style of government differed from that of his father. In the beginning of the sixth reign, the king continued to use his father's team and there was no sudden break in the daily routine of government. Much of the running of daily affairs was therefore in the hands of experienced and competent men. To them and their staff Siam owed many progressive steps, such as the development of a national plan for the education of the whole populace, the setting up of clinics where free vaccination was given against smallpox, and the continuing expansion of railways.

However, senior posts were gradually filled with members of the king's coterie when a vacancy occurred through death, retirement, or resignation. By 1915, half the cabinet consisted of new faces. Most notable was Chao Phraya Yomarat's presence and Prince Damrong's absence. He resigned from his post as Minister of the Interior officially because of ill health, but in actuality because of friction between himself and the king.

Educational reform

Rama VI was the first king of Siam to set up a model of the constitution at Dusit Palace. He wanted first to see how things could be managed under this Western system. He saw advantages in the system, and thought that Siam could move slowly towards it, but could not be adopted right away as the majority of the Siamese people did not have enough education to understand such a change just yet. In 1916 higher education came to Siam. Rama VI set up Vajiravudh College, modeled after the British Eton College, as well as the first Thai university, Chulalongkorn University,[19] modeled after Oxbridge.

-

Vajiramonkut Building, Vajiravudh College.

-

Vajiravudh College.

-

Maha Chulalongkorn Building, Chulalongkorn University.

World War I

|

|

| King Rama VI by royal command changed the national flag of Siam in 1917 from the white elephant on a red background to a design with colors inspired by those of the Allies. |

In 1917 Siam declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary, mainly to curry favor with the British and the French. Siam's token participation in World War I secured it a seat at the Versailles Peace Conference, and Foreign Minister Devawongse used this opportunity to argue for the repeal of 19th century treaties and the restoration of full Siamese sovereignty. The United States obliged in 1920, while France and Britain delayed until 1925. This victory gained the king some popularity, but it was soon undercut by discontent over other issues, such as his extravagance, which became more noticeable when a sharp postwar recession hit Siam in 1919. There was also concern that the king had no son, which undermined the stability of the monarchy due to the absence of heirs[citation needed].

Thus when Rama VI died suddenly in 1925, aged only 44, the monarchy was in a weakened state. He was succeeded by his younger brother Prajadhipok.

The end of absolute rule (1925–1932)

Unprepared for his new responsibilities, all Prajadhipok had in his favor was a lively intelligence, a charming diplomacy in his dealings with others, modesty and industrious willingness to learn, and the somewhat tarnished, but still potent, allure of the crown.

Unlike his predecessor, the king diligently read virtually all state papers that came his way, from ministerial submissions to petitions by citizens. Within half a year, only three of Vajiravhud's twelve ministers stayed put, the rest having been replaced by members of the royal family. On the one hand, these appointments brought back men of talent and experience; on the other, it signaled a return to royal oligarchy. The king obviously wanted to demonstrate a clear break with the discredited sixth reign, and the choice of men to fill the top positions appeared to be guided largely by a wish to restore a Chulalongkorn-type government.

The legacy that Prajadhipok received from his elder brother were problems of the sort that had become chronic in the Sixth Reign. The most urgent of these was the economy: the finances of the state were in chaos, the budget heavily in deficit, and the royal accounts a nightmare of debts and questionable transactions. That the rest of the world was deep in the Great Depression following World War I did not help the situation either.

Virtually the first act of Prajadipok as king entailed an institutional innovation intended to restore confidence in the monarchy and government, the creation of the Supreme Council of the State. This privy council was made up of a number of experienced and extremely competent members of the royal family, including the longtime Minister of the Interior (and Chulalongkorn's right-hand man) Prince Damrong. Gradually these princes arrogated increasing power by monopolizing all the main ministerial positions. Many of them felt it their duty to make amends for the mistakes of the previous reign, but it was not generally appreciated.

With the help of this council, the king managed to restore stability to the economy, although at a price of making a significant number of the civil servants redundant and cutting the salary of those that remained. This was obviously unpopular among the officials, and was one of the trigger events for the coup of 1932.

Prajadhipok then turned his attention to the question of future politics in Siam. Inspired by the British example, the king wanted to allow the common people to have a say in the country's affair by the creation of a parliament. A proposed constitution was ordered to be drafted, but the king's wishes were rejected by his advisers, who felt that the population was not yet ready for democracy.

Revolution

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the Supreme Council opted to introduce cuts in spending, including the military budget. The king foresaw that these policies might create discontent, especially in the army, and he therefore convened a special meeting of officials to explain why the cuts were necessary. In his address he stated the following, "I myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam."

No previous monarch of Siam had ever spoken in such terms. Many interpreted the speech not as Prajadhipok apparently intended, namely as a frank appeal for understanding and cooperation. They saw it as a sign of his weakness and evidence that a system which perpetuated the rule of fallible autocrats should be abolished. Serious political disturbances were threatened in the capital, and in April the king agreed to introduce a constitution under which he would share power with a prime minister. This was not enough for the radical elements in the army, however. On 24 June 1932, while the king was at the seaside, the Bangkok garrison mutinied and seized power, led by a group of 49 officers known as "Khana Ratsadon". Thus ended 800 years of absolute monarchy.

Culture

Clothing

Old Rattanakosin

As same as Ayutthaya period, both Thai males and females dressed themselves with a loincloth wrap called chong kraben. Men wore their chong kraben to cover the waist to halfway down the thigh, while women covered the waist to well below the knee.[20] Bare chests and bare feet were accepted as part of the Thai formal dress code, and is observed in murals, illustrated manuscripts, and early photographs up to the middle of the 1800s.[20] However, after the Second Fall of Ayutthaya, central Thai women began cutting their hair in a crew-cut short style, which remained the national hairstyle until the 1900s.[21] Prior to the 20th century, the primary markers that distinguished class in Thai clothing were the use of cotton and silk cloths with printed or woven motifs, but both commoners and royals alike wore wrapped, not stitched clothing.[22]

Modern Rattanakosin

From the 1860s onward, Thai royals "selectively adopted Victorian corporeal and sartorial etiquette to fashion modern personas that were publicized domestically and internationally by means of mechanically reproduced images."[22] Stitched clothing, including court attire and ceremonial uniforms, were invented during the reign of King Chulalongkorn.[22] Western forms of dress became popular among urbanites in Bangkok during this time period.[22] During the early 1900s, King Vajiravudh launched a campaign to encourage Thai women to wear long hair instead of traditional short hair, and to wear pha sinh (ผ้าซิ่น), a tubular skirt, instead of the chong kraben (โจงกระเบน), a cloth wrap.[23]

Architecture

See also

References

- ^ "Rattanakosin Period (1782 -present)". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ "Historic City of Ayutthaya". © UNESCO World Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "The Thon Buri and Early Bangkok periods". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "THE EARLY CHAKRI KINGS AND A RESURGENT SIAM". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Prominent Mon Lineages from Late Ayutthaya to Early Bangkok" (PDF). Siamese-heritage.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b Dilokwanich, Malinee. "A STUDY OF SAMKOK: The First Thai Translation of a Chinese Novel" (PDF). Siamese Heritage. p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Wales, H. G. Quaritch (14 April 2005) [First published in 1931]. Siamese state ceremonies. London: Bernard Quaritch. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ Nolan, Cathal J. (2002). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: S-Z by Cathal J. Nolan. ISBN 9780313323836. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Chris Baker, Pasuk Phongpaichit (2005). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-521-81615-7.

- ^ Urban Council. Sculptures from Thailand: 16.10.82–12.12.82, Hong Kong Museum. University of California. p. 33.

- ^ Dhani Nivat, Prince (1955). "The Reconstruction of Rama I of the Chakri Dynasty" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 43 (1). Siam Society Heritage Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

First page of the Law Code of 1805

- ^ a b c Nicholas Tarling (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35505-2.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Crawford Papers — A Collection of Official Records relating to the Mission of Dr. John Crawfurd sent to Siam by the Government of India in the year 1821". Cambridge.org. Cambridge Journals Online. 1971. p. 285. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ David K. Wyatt (2004). Thailand: A Short History (2nd ed.). Silkworm Books. p. 165.

- ^ Charles F. Keyes (1997) The Golden Peninsula: Culture and Adaptation in Mainland Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824816964, p. 104

- ^ Lopez 2013, p. 696.

- ^ "Southern Thailand: The Problem with Paramilitaries" (PDF). Asia Report. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Bing Soravij BhiromBhakdi. "Rama VI of the Chakri Dynasty". The Siamese Collection. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b Terwiel, Barend Jan (2007). "The Body and Sexuality in Siam: A First Exploration in Early Sources" (PDF). Manusya: Journal of Humanities. 10 (14): 42–55. doi:10.1163/26659077-01004003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Jotisalikorn, Chami (2013). Thailand's Luxury Spas: Pampering Yourself in Paradise. Tuttle Publishing. p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Peleggi, Maurizio (2010). Mina Roces (ed.). The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781845193997.

- ^ Sarutta (10 September 2002). "Women's Status in Thai Society". Thaiways Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Greene, Stephen Lyon Wakeman. Absolute Dreams. Thai Government Under Rama VI, 1910–1925. Bangkok: White Lotus, 1999

External links

- Rattanakosin Kingdom

- History of Thailand

- History of Cambodia

- History of Laos

- History of Malaysia

- 1780s in Siam

- 1790s in Siam

- 18th century in Siam

- 19th century in Siam

- 20th century in Thailand

- States and territories established in 1782

- States and territories disestablished in 1932

- 1782 establishments in Siam

- Former polities of the interwar period