Australian Senate

Australian Senate | |

|---|---|

| 45th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 76 |

| |

Political groups | Government (30) Coalition |

| Elections | |

| Single transferable vote | |

Last election | 2 July 2016 |

Next election | 2019 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Senate chamber Parliament House Canberra, ACT, Australia | |

| Website | |

| Senate

| |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Australia |

|---|

|

| Constitution |

|

|

The Australian Senate is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter I, Part II of the Australian Constitution. There are a total of 76 senators: 12 senators are elected from each of the six states (regardless of population) and two from each of the two autonomous internal territories (the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory). Senators are popularly elected under a single transferable vote system of proportional representation. There is no constitutional requirement for the election of senators to take place at the same time as those for members of the House of Representatives, though the government usually synchronises election dates.

Unlike upper houses in most Westminster parliamentary systems, the Senate is vested with significant power, including the capacity to block legislation initiated by the government in the House of Representatives, making it a distinctive hybrid of British Westminster bicameralism and US-style bicameralism.

Senators normally serve fixed six-year terms (from 1 July to 30 June), unless the Senate is dissolved earlier in a double dissolution. Following a double dissolution half the state senators serve terms ending on the third 30 June following the election (i.e. slightly less than three years) with the rest serving three years longer. The term of the territory senators expires at the same time as there is an election for the House of Representatives.

The previous Parliament was elected at the 2013 election, and was the 44th Federal Parliament since Federation. The six-year term of the 36 state senators who were elected in 2013 commenced on 1 July 2014. The terms of all Senators ended on the dissolution of the Parliament in May 2016.

The 2016 double dissolution election Senate result was announced on 4 August: Liberal/National Coalition 30 seats (−3), Labor 26 seats (+1), Greens 9 seats (−1), One Nation 4 seats (+4) and Nick Xenophon Team 3 seats (+2). Derryn Hinch won a seat, while Liberal Democrat David Leyonhjelm, Family First's Bob Day, and Jacqui Lambie retained their seats. The number of crossbenchers increased by two to a record 20. The Liberal/National Coalition will require at least nine additional votes to reach a Senate majority, an increase of three.[1][2][3] The Liberal/National Coalition and Labor parties agreed that the first elected six of twelve Senators in each state would serve six-year terms, while the last six elected in each state would serve three-year terms.[4]

Origins and role

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (Imp.) of 1900 established the Senate as part of the new system of dominion government in newly federated Australia. From a comparative governmental perspective, the Australian Senate exhibits distinctive characteristics. Unlike upper houses in other Westminster system governments, the Senate is not a vestigial body with limited legislative power. Rather it was intended to play – and does play – an active role in legislation. Rather than being modelled solely after the House of Lords, as the Canadian Senate was, the Australian Senate was in part modelled after the United States Senate, by giving equal representation to each state. The Constitution intended to give less populous states added voice in a Federal legislature, while also providing for the revising role of an upper house in the Westminster system.

Although the Prime Minister, by convention, serves as a member of the House of Representatives, other ministers may come from either house, and the two houses have almost equal legislative power. As with most upper chambers in bicameral parliaments, the Senate cannot introduce appropriation bills (bills that authorise government expenditure of public revenue) or bills that impose taxation, that role being reserved for the lower house. That degree of equality between the Senate and House of Representatives reflects the desire of the Constitution's authors to address smaller states' desire for strong powers for the Senate as a way of ensuring that the interests of more populous states as represented in the House of Representatives did not totally dominate the government. This situation was also partly due to the age of the Australian constitution – it was enacted before the confrontation in 1909 in Britain between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, which ultimately resulted in the restrictions placed on the powers of the House of Lords by the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949.

In practice, however, most legislation (except for private member's bills) in the Australian Parliament is initiated by the Government, which has control over the lower house. It is then passed to the Senate, which has the opportunity to amend the bill or refuse to pass it. In the majority of cases, voting takes place along party lines, although there are occasional conscience votes.

Since 2015, armed officers of the Australian Federal Police have been placed on duty to protect both chambers of the Federal Parliament.[5]

Nexus

The number of members of the House of Representatives has to be "as nearly as practicable" double the number of Senators. The reasons for the nexus are twofold:

- maintain a constant influence for the smaller states.

- maintain a constant balance of the two houses in case of a joint sitting after a double dissolution.

A referendum held in 1967 to eliminate the nexus failed to pass.

Where the houses disagree

If the Senate rejects or fails to pass a proposed law, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree, and if after an interval of three months the Senate refuses to pass the same piece of legislation, the government may either abandon the bill or continue to revise it, or, in certain circumstances outlined in section 57 of the Constitution, the Prime Minister can advise the Governor-General to dissolve the entire parliament in a double dissolution. In such an event, the entirety of the Senate faces re-election, as does the House of Representatives, rather than only about half the chamber as is normally the case. After a double dissolution election, if the bills in question are reintroduced, and if they again fail to pass the Senate, the Governor-General may agree to a joint sitting of the two houses in an attempt to pass the bills. Such a sitting has only occurred once, in 1974.

The double dissolution mechanism is not available for bills that originate in the Senate and are blocked in the lower house.

After a double dissolution election, section 13 of the Constitution requires the Senate to divide the senators into two classes, with the first class having a three-year "short term", and the second class a six-year "long term". The Senate may adopt one of two approaches to determine how to allocate the long and short terms:

- "elected-order" method, where the Senators elected first attain a six-year term. This approach tends to favour minor party candidates as it gives greater weight to their first preference votes;[6] or

- re-count method, where the long terms are allocated to those Senators who would have been elected first if the election had been a standard half-Senate election.[7] This method is likely to be preferred by the major parties in the Senate where it would deliver more six-year terms to their members.[6]

The Senate applied the "elected-order" method following the 1987 double dissolution election.[7] Since that time the Senate has passed resolutions on several occasions indicating its intention to use the re-count method to allocate seats at any future double dissolution, which Green describes as a fairer approach but notes could be ignored if a majority of Senators opted for the "elected-order" method instead.[7]

On 8 October 2003, the then Prime Minister John Howard initiated public discussion of whether the mechanism for the resolution of deadlocks between the houses should be reformed. High levels of support for the existing mechanism, and a very low level of public interest in that discussion, resulted in the abandonment of these proposals.[8]

Blocking supply

The constitutional text denies the Senate the power to originate or amend appropriation bills, in deference to the conventions of the classical Westminster system. Under a traditional Westminster system, the executive government is responsible for its use of public funds to the lower house, which has the power to bring down a government by blocking its access to supply – i.e. revenue appropriated through taxation. The arrangement as expressed in the Australian Constitution, however, still leaves the Senate with the power to reject supply bills or defer their passage – undoubtedly one of the Senate's most contentious and powerful abilities.

The ability to block supply was the origin of the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis. The Opposition used its numbers in the Senate to defer supply bills, refusing to deal with them until an election was called for both Houses of Parliament, an election which it hoped to win. The Prime Minister of the day, Gough Whitlam, contested the legitimacy of the blocking and refused to resign. The crisis brought to a head two Westminster conventions that, under the Australian constitutional system, were in conflict – firstly, that a government may continue to govern for as long as it has the support of the lower house, and secondly, that a government that no longer has access to supply must either resign or be dismissed. The crisis was resolved in November 1975 when Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Whitlam's government and appointed a caretaker government on condition that elections for both houses of parliament be held. This action in itself was a source of controversy and debate continues on the proper usage of the Senate's ability to block supply and on whether such a power should even exist.

The blocking of supply alone cannot force a double dissolution. There must be legislation repeatedly blocked by the Senate which the government can then choose to use as a trigger for a double dissolution.[9]

Electoral system

The system for electing senators has changed twice since Federation. The original arrangement involved a first-past-the-post block voting or "winner takes all" system, on a state-by-state basis. This was replaced in 1919 by preferential block voting. Block voting tended to produce landslide majorities and even "wipe-outs". For instance, from 1920 to 1923 the Nationalist Party of Australia had 35 of the 36 senators, and from 1947 to 1950, the Australian Labor Party had 33 of the 36 senators.

In 1948, single transferable vote proportional representation on a state-by-state basis became the method for electing senators. From the 1984 election, group ticket voting was introduced in order to reduce informal voting. In 2016 group tickets were abolished to avoid undue influence of preference deals[10] and optional preferential voting was used instead.

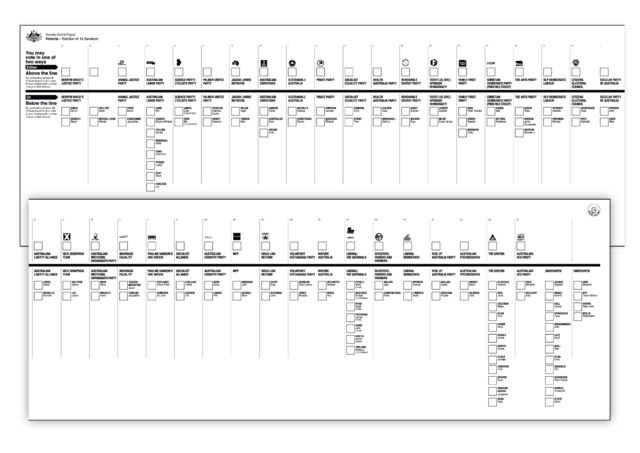

Ballot paper

The Australian Senate voting paper under the single transferable vote proportional representation system resembles the following example (shown in two parts), which shows the candidates for Victorian senate representation in the 2016 federal election.

To vote correctly as a result of Senate voting changes implemented before the 2016 federal election, electors must:

- Vote for at least six parties above the thick black line, by writing the numbers 1-6 in party boxes. Votes with less than six boxes numbered are still admitted to the count through savings provisions.

- Vote for at least twelve candidates below the thick black line, by writing the numbers 1-12 in the individual candidates' boxes. Votes with between six and twelve boxes numbered are still admitted to the count through savings provisions.

Prior to 2016, electors had to either:

- Vote for an individual party by writing the number 1 in a single box above the thick black line – this means the elector wants their preferences distributed according to a party's or group's officially registered group voting ticket; or

- Vote for all candidates, starting with the number 1 and finishing when all the individual boxes below the line are numbered.

Because each state elects six senators at each half-senate election, the quota for election is only one-seventh or 14.3% (one third or 33.3% for territories, where only two senators are elected). Once a candidate has been elected with votes reaching the quota amount, any votes they receive in addition to this may be distributed to other candidates as preferences.

With an odd number of seats in a half-Senate election (3 or 5), 50.1% of the vote wins a majority (2/3) or (3/5).

With an even number of seats in a half-Senate election (6), 57.1% of the vote is needed to win a majority of seats (4/6).

The ungrouped candidates in the far right column do not have a box above the line. Therefore, they can only get a primary (number 1) vote from electors who vote below the line. For this reason, some independents register as a group, either with other independents or by themselves, such as groups F and G in the above example.

Names of parties can be shown only if the parties are registered, which requires, among other things, a minimum of 500 members.

Order of parties

The order of parties on the ballot papers, and the order of ungrouped candidates is determined by a ballot conducted by the Electoral Commission.

Deposit

Candidates, parties, and groups pay a deposit of $2000 per candidate, which is forfeited if they fail to achieve 4% of the primary vote.

Public subsidy

Candidates, parties, and groups earn a public subsidy if they gain at least 4% of the primary vote. At the 2013 federal election, funding was $2.488 per formal first preference vote.

2016 Senate voting changes

Following the 2013 election, the Abbott Liberal government announced it would investigate changing the electoral system for the Senate. On 22 February 2016, the Turnbull Liberal government announced several proposed changes.[11] In the Senate, the changes had the support of the Liberal/National Coalition, the Australian Greens, and Nick Xenophon − a three-vote majority.[12] The legislation passed both houses of the Parliament of Australia on 18 March 2016 after the Senate sat all night debating the bill.[13]

The changes abolished group voting tickets and introduced optional preferential voting, along with party logos on the ballot paper. The ballot paper continues to have a box for each party above a heavy line, with each party's candidates in a column below that party's box below the solid line. Previously, a voter could either mark a single box above the line, which triggered the party's group voting ticket (a pre-assigned sequence of preferences), or place a number in every box below the line to assign their own preferences. As a result of the changes, voters may assign their preferences for parties above the line (numbering as many boxes as they wish), or individual candidates below the line, and are not required to fill all of the boxes. Both above and below the line voting are now optional preferential voting. For above the line, voters will be instructed to write at least their first six preferences; however, a "savings provision" will still count the ballot if less than six were given. As a result, fewer votes are expected to be classed as informal, but more ballots will "exhaust" as a result (i.e. some votes are not counted towards electing any candidate). For below the line, voters will be required to write at least their first 12 preferences. Voters will be free to continue numbering as many preferences as they like beyond the minimum number specified. Another savings provision will allow ballot papers with at least 6 below the line preferences to be formal, catering for people who confuse the above and below the line instructions.

The 2016 Senate voting changes were subject to a High Court Challenge by sitting Senator Bob Day of the Family First Party, South Australia Branch. The senator argued that the changes meant the senators would not be "directly chosen by the people" as required by the constitution. The High Court decided that both above the line and below the line voting were valid methods for the people to choose their Senators.[14]

Membership

Under sections 7 and 8 of the Australian Constitution,:[15]

- the Senate must comprise an equal number of senators from each original state,

- each original state shall have at least six senators, and

- the Senate must be elected in a way that is not discriminatory among the states.

These conditions have periodically been the source of debate, and within these conditions, the composition and rules of the Senate have varied significantly since federation.

Size

The size of the Senate has changed over the years. The Constitution originally provided for 6 senators for each state, resulting in a total of 36 senators. The Constitution permits the Parliament to increase the number of senators, provided that equal numbers of senators from each original state are maintained. Accordingly, in 1948, Senate representation was increased to 10 senators for each state, increasing the total to 60.

In 1975, the two territories, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory, were given an entitlement to elect two senators each for the first time, bringing the number to 64.[16] The senators from the Northern Territory also represent constituents from Australia's Indian Ocean Territories (Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands), while the senators from the Australian Capital Territory also represent voters from the Jervis Bay Territory and since 1 July 2016, Norfolk Island.[17]

The latest expansion in Senate numbers took place in 1984, when the number of senators from each state was increased to 12, resulting in a total of 76 senators.[18]

Term

Normally, elections for senators take place at the same time as those for members of the House of Representatives. However, because their terms do not coincide, the incoming Parliament will for some time comprise a new House of Representatives and an old Senate.

Section 13 of the Constitution requires that in half-Senate elections the election of State senators shall take place within one year before the places become vacant. The actual election date is determined by the Governor of each State, who acts on the advice of the State Premier. The Governors almost always act on the recommendation of the Governor-General, with the last independent Senate election writ being issued by the Governor of Queensland during the Gair Affair in 1974.

Slightly more than half of the Senate is contested at each general election (half of the 72 state senators, and all four of the territory senators), along with the entire House of Representatives. Except in the case of a double dissolution, senators are normally elected for fixed terms of six years, commencing on 1 July following the election, and ceasing on 30 June six years later.

The term of the four senators from the territories is not fixed, but is defined by the dates of the general elections for the House of Representatives, the period between which can vary greatly, to a maximum of three years and three months. Territory senators commence their terms on the day that they are elected. Their terms expire the day prior to the following general election day.[19]

Following a double dissolution, all 76 senators face re-election. If there is an early House election outside the 12-month period in which Senate elections can occur, the synchronisation of the election will be disrupted, and there can be elections at which only half the Senate is up for election. The last time this occurred was on 21 November 1970.

Issues with equal representation

Each state elects the same number of senators, meaning there is equal representation for each of the Australian states, regardless of population, so the Senate, like many upper houses, does not adhere to the principle of "one vote one value". Tasmania, with a population of around 500,000, elects the same number of senators as New South Wales, which has a population of over 7 million. Because of this imbalance, governments favoured by the more populous states are occasionally frustrated by the extra power the smaller states have in the Senate, to the degree that former Prime Minister Paul Keating famously referred to the Senate's members as "unrepresentative swill".[20] The proportional election system within each state ensures that the Senate incorporates more political diversity than the lower house, which is basically a two party body. The elected membership of the Senate more closely reflects the first voting preference of the electorate as a whole than does the composition of the House of Representatives, despite the large discrepancies from state to state in the ratio of voters to senators.[21][22] This often means that the composition of the Senate is different from that of the House of Representatives, contributing to the Senate's function as a house of review.

While the states are equally represented in the Senate, which was originally regarded as the "State's House", the Senate has no power to amend or initiate "money" bills.[23] Hence representation in the Senate is not quite equal. For the first 10 years of Federation, parties were weak and fluid, but after this time, the "state's house" attribute disappeared, and the Senate became a party's house as well.[citation needed]

With proportional representation, and the small majorities in the Senate compared to the generally larger majorities in the House of Representatives, and the requirement that the number of members of the House be "nearly as practicable" twice that of the Senate, a joint sitting after a double dissolution is more likely than not to lead to a victory for the House over the Senate. When the Senate had an odd number of Senators retiring at an election (3 or 5), 51% of the vote would lead to a clear majority of 3 out of 5 per state. With an even number of Senators retiring at an election, it takes 57% of the vote to win 4 out of 6 seats, which may be insurmountable. This gives the House an unintended extra advantage in joint sittings but not in ordinary elections, where the Senate may be too evenly balanced to get House legislation through.

The Government does not need the support of the Senate to stay in office, unless the Senate blocks or defers supply. However, if the governing party does not have a majority in the Senate, it can often find its agenda frustrated in the upper house. This can be the case even when the government has a large majority in the House.

Parties

The overwhelming majority of senators have always been elected as representatives of political parties. Parties which currently have representation in the Senate are:

- The Coalition – Liberal Party of Australia, Liberal National Party of Queensland, National Party of Australia and Country Liberal Party

- Australian Labor Party

- Australian Greens

- Pauline Hanson's One Nation

- Nick Xenophon Team

- Jacqui Lambie Network

- Derryn Hinch's Justice Party

- Liberal Democratic Party

- Family First

Other parties that have achieved Senate representation in the past include the Australian Democrats, Palmer United Party, Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party, Nuclear Disarmament Party, Liberal Movement, the Democratic Labour Party and the related but separate Democratic Labor Party.

Due to the need to obtain votes statewide, independent candidates have difficulty getting elected. The exceptions in recent times have been elected in less populous States – the former Tasmanian Senator Brian Harradine and the current South Australian Senator Nick Xenophon.

The Australian Senate serves as a model for some politicians in Canada, particularly in the Western provinces, who wish to reform the Canadian Senate so that it takes a more active legislative role.[24]

There are also small factions in the United Kingdom (both from the right and left) who wish to the see the House of Lords take on a structure similar to that of the Australian Senate.[who?]

Casual vacancies

Section 15 of the Constitution provides that a casual vacancy of a State senator shall be filled by the State Parliament. If the previous senator was a member of a particular political party the replacement must come from the same party, but the State Parliament may choose not to fill the vacancy, in which case Section 11 requires the Senate to proceed regardless. If the State Parliament happens to be in recess when the vacancy occurs, the Constitution provides that the State Governor can appoint someone to fill the place until fourteen days after the State Parliament resumes sitting.

Procedure

Work

The Australian Senate typically sits for 50 to 60 days a year.[a] Most of those days are grouped into 'sitting fortnights' of two four-day weeks. These are in turn arranged in three periods: the autumn sittings, from February to April; the winter sittings, which commence with the delivery of the budget in the House of Representatives on the first sitting day of May and run through to June or July; and the spring sittings, which commence around August and continue until December, and which typically contain the largest number of the year's sitting days.

The senate has a regular schedule that structures its typical working week.[26]

Dealing with legislation

All bills must be passed by a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate before they become law. Most bills originate in the House of Representatives, and the great majority are introduced by the government.

The usual procedure is for notice to be given by a government minister the day before the bill is introduced into the Senate. Once introduced the bill goes through several stages of consideration. It is given a first reading, which represents the bill's formal introduction into the chamber.

The first reading is followed by debate on the principle or policy of the bill (the second reading debate). Agreement to the bill in principle is indicated by a second reading, after which the detailed provisions of the bill are considered by one of a number of methods (see below). Bills may also be referred by either House to their specialised standing or select committees. Agreement to the policy and the details is confirmed by a third and final reading. These processes ensure that a bill is systematically considered before being agreed to.[27]

The Senate has detailed rules in its standing orders that govern how a bill is considered at each stage.[28] This process of consideration can vary greatly in the amount of time taken. Consideration of some bills is completed in a single day, while complex or controversial legislation may take months to pass through all stages of Senate scrutiny. The Constitution provides that if the Senate vote is equal, the question shall pass in the negative.

Committees

In addition to the work of the main chamber, the Senate also has a large number of committees which deal with matters referred to them by the Senate. These committees also conduct hearings three times a year in which the government's budget and operations are examined. These are known as estimates hearings. Traditionally dominated by scrutiny of government activities by non-government senators, they provide the opportunity for all senators to ask questions of ministers and public officials. This may occasionally include government senators examining activities of independent publicly funded bodies, or pursuing issues arising from previous governments' terms of office. There is however a convention that senators do not have access to the files and records of previous governments when there has been an election resulting in a change in the party in government.

Holding governments to account

One of the functions of the Senate, both directly and through its committees, is to scrutinise government activity. The vigour of this scrutiny has been fuelled for many years by the fact that the party in government has seldom had a majority in the Senate. Whereas in the House of Representatives the government's majority has sometimes limited that chamber's capacity to implement executive scrutiny, the opposition and minor parties have been able to use their Senate numbers as a basis for conducting inquiries into government operations. When the Howard government won control of the Senate in 2005, it sparked a debate about the effectiveness of the Senate in holding the government of the day accountable for its actions. Government members argued that the Senate continued to be a forum of vigorous debate, and its committees continued to be active.[29] The Opposition leader in the Senate suggested that the government had attenuated the scrutinising activities of the Senate.[30] The Australian Democrats, a minor party which frequently played mediating and negotiating roles in the Senate, expressed concern about a diminished role for the Senate's committees.[31]

Voting

Senators are called upon to vote on matters before the Senate. These votes are called divisions in the case of Senate business, or ballots where the vote is to choose a senator to fill an office of the Senate (such as President of the Australian Senate).[32]

Party discipline in Australian politics is extremely tight, so divisions almost always are decided on party lines. Nevertheless, the existence of minor parties holding the balance of power in the Senate has made divisions in that chamber more important and occasionally more dramatic than in the House of Representatives.

When a division is to be held, bells ring throughout the parliament building for four minutes, during which time senators must go to the chamber. At the end of that period the doors are locked and a vote is taken, by identifying and counting senators according to the side of the chamber on which they sit (ayes to the right of the chair, noes to the left). The whole procedure takes around eight minutes. Senators with commitments that keep them from the chamber may make arrangements in advance to be 'paired' with a senator of the opposite political party, so that their absence does not affect the outcome of the vote.

The Senate contains an even number of senators, so a tied vote is a real prospect (which regularly occurs when the party numbers in the chamber are finely balanced). Section 23 of the Constitution requires that in the event of a tied division, the question is resolved in the negative. The system is however different for ballots for offices such as the President. If such a ballot is tied, the Clerk of the Senate decides the outcome by the drawing of lots. In reality, conventions govern most ballots, so this situation does not arise.

Political parties and voting outcomes

The extent to which party discipline determines the outcome of parliamentary votes is highlighted by the rarity with which members of the same political party will find themselves on opposing sides of a vote. The exceptions are where a conscience vote is allowed by one or more of the political parties; and occasions where a member of a political party crosses the floor of the chamber to vote against the instructions of their party whip. Crossing the floor very rarely occurs, but is more likely in the Senate than in the House of Representatives.[33]

One feature of the government having a majority in both chambers between 1 July 2005 and the 2007 elections was the potential for an increased emphasis on internal differences between members of the government parties.[34] This period saw the first instances of crossing the floor by senators since the conservative government took office in 1996:[35] Gary Humphries on civil unions in the Australian Capital Territory, and Barnaby Joyce on voluntary student unionism.[36] A more significant potential instance of floor crossing was averted when the government withdrew its Migration Amendment (Designated Unauthorised Arrivals) Bill, of which several government senators had been critical, and which would have been defeated had it proceeded to the vote.[37] The controversy that surrounded these examples demonstrated both the importance of backbenchers in party policy deliberations and the limitations to their power to influence outcomes in the Senate chamber.

In September 2008, Barnaby Joyce became leader of the Nationals in the Senate, and stated that his party in the upper house would no longer necessarily vote with their Liberal counterparts.[38]

Party composition

Historical

The Senate has included representatives from a range of political parties, including several parties that have seldom or never had representation in the House of Representatives, but which have consistently secured a small but significant level of electoral support, as the table shows.[b]

| Plurality-at-large voting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | ALP | Prot. | Free T. | Other |

| 1901–1903 | 36 | 8 | 11 | 17 | |

| 1903–1906 | 36 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 2 (Trenwith, 1 RTP) |

| 1906–1910 | 36 | 15 | 6 | 14 (AS) | 1 (Trenwith) |

| Year | Total | ALP | Cmlth Liberal | Other | |

| 1910–1913 | 36 | 22 | 14 | ||

| 1913–1914 | 36 | 29 | 7 | ||

| 1914–1917 | 36 | 31 | 5 | ||

| Year | Total | ALP | Nationalist | Other | |

| 1917–1920 | 36 | 12 | 24 | ||

| Preferential block voting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | ALP | Nationalist | ||

| 1920–1923 | 36 | 1 | 35 | ||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | ||

| 1923–1926 | 36 | 12 | 24 | ||

| 1926–1929 | 36 | 8 | 28 | ||

| 1929–1932 | 36 | 7 | 29 | ||

| 1932–1935 | 36 | 10 | 26 | ||

| 1935–1938 | 36 | 3 | 33 | ||

| 1938–1941 | 36 | 16 | 20 | ||

| 1941–1944 | 36 | 17 | 19 | ||

| 1944–1947 | 36 | 22 | 14 | ||

| 1947–1950 | 36 | 33 | 3 | ||

| Single transferable vote | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | DLP | Other | ||||||||||

| 1950–1951 | 60 | 34 | 26 | ||||||||||||

| 1951–1953 | 60 | 28 | 32 | ||||||||||||

| 1953–1956 | 60 | 29 | 31 | ||||||||||||

| 1956–1959 | 60 | 28 | 30 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 1959–1962 | 60 | 26 | 32 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 1962–1965 | 60 | 28 | 30 | 1 | 1 (Turnbull) | ||||||||||

| 1965–1968 | 60 | 27 | 30 | 2 | 1 (Turnbull) | ||||||||||

| 1968–1971 | 60 | 27 | 28 | 5 | 1 (Turnbull) | ||||||||||

| 1971–1974 | 60 | 26 | 26 | 5 | 3 (Turnbull, Townley, Negus) | ||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | LM/AD | Other | ||||||||||

| 1974–1975 | 60 | 29 | 29 | 1 | 1 (Townley) | ||||||||||

| 1975–1978 | 64 | 27 | 35 | 1 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| 1978–1981 | 64 | 26 | 35 | 2 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| 1981–1983 | 64 | 27 | 31 | 5 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| 1983–1985 | 64 | 30 | 28 | 5 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| Single transferable vote (Group voting ticket) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | AD | NDP | Other | |||||||||||

| 1985–1987 | 76 | 34 | 33 | 7 | 1 | 1 (Harradine) | |||||||||||

| 1987–1990 | 76 | 32 | 34 | 7 | 1 | 2 (Harradine, Vallentine) | |||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | AD | Greens | Other | |||||||||||

| 1990–1993 | 76 | 32 | 34 | 8 | 1 | 1 (Harradine) | |||||||||||

| 1993–1996 | 76 | 30 | 36 | 7 | 2 | 1 (Harradine) | |||||||||||

| 1996–1999 | 76 | 28 | 37 | 7 | 2 | 2 (Harradine, Colston) | |||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | AD | Greens | ON | Other | ||||||||||

| 1999–2002 | 76 | 29 | 35 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| 2002–2005 | 76 | 29 | 35 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 (Harradine) | ||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | AD | Greens | FF | Other | ||||||||||

| 2005–2008 | 76 | 28 | 39 | 4 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2008–2011 | 76 | 32 | 37 | 5 | 1 | 1 (Xenophon) | |||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | DLP | Greens | Other | |||||||||||

| 2011–2014 | 76 | 31 | 34 | 1 | 9 | 1 (Xenophon) | |||||||||||

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | DLP | Greens | FF | PUP | LDP | AMEP | Other | |||||||

| 2014-2016 | 76 | 25 | 33 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | from 1 to 4 [c] | |||||||

| Single transferable vote (Optional preferential voting) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | ALP | Coalition | Greens | ON | FF | NXT | LDP | Other | ||||||

| 2016-2019 | 76 | 26 | 30 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 (Lambie, Hinch) | ||||||

See also

- Members of the Australian Senate, 2016–2019

- President of the Australian Senate

- Double dissolution

- Women in the Australian Senate

- Clerk of the Australian Senate

- Members of the Parliament of Australia who have served for at least 30 years

- Father of the Australian Senate

- List of Australian Senate appointments

- Canberra Press Gallery

Notes

- ^ Figures are available for each year on the Senate StatsNet[25]

- ^ The table has been simplified in the following ways:

- Liberal, National, United Australia Party, Nationalist Party and Country Liberal members are grouped as Coalition.

- Greens Western Australia members are grouped together with Australian Greens.

- ^ Xenophon; Madigan (from DLP); Lambie, Lazarus (from PUP)

References

- ^ AEC: Twitter

- ^ "Federal Election 2016: Senate Results". Australia Votes. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 July 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Senate photo finishes". Blogs.crikey.com.au. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Cormann raises ‘first elected’ plan to halve Senate terms for crossbenchers: The Australian 12 December 2016

- ^ Armed guards now stationed to protect Australian MPs and senators in both chambers of Federal Parliament: SMH 9 February 2015

- ^ a b Uma Patel (6 July 2016). "Election 2016: How do we decide which senators are in for three years and which are in for six?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ a b c Antony Green (25 April 2016). "How Long and Short Senate Terms are Allocated After a Double Dissolution". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Consultative Group on Constitutional Change (March 2004). "Resolving Deadlocks: The Public Response" (PDF). p. 8.

- ^ Green, Antony. "An Early Double Dissolution? Don't Hold Your Breath!". Antony Green's Election Blog. ABC. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Senate voting changes explained in Australian Electoral Commission advertisements By political reporter Stephanie Anderson. Posted Tue at 12:00am

- ^ Senate election reforms announced, including preferential voting above the line, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 22 February 2016

- ^ Explainer: what changes to the Senate voting system are being proposed?, Stephen Morey, The Conversation, 23 February 2016

- ^ Electoral laws passed after marathon Parliament sitting: ABC 18 March 2016

- ^ Day v Australian Electoral Officer for the State of South Australia [2016] HCA 20

- ^ "Chapter 4, Odgers' Australian Senate Practice". Aph.gov.au. 2 February 2010. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Senate (Representation of Territories) Act 1973. No. 39, 1974

- ^ "Norfolk Island Electors". Australian Electoral Commission. 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Department of the Senate, Senate Brief No. 1, 'Electing Australia's Senators' Archived 29 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 2007.

- ^ Section 6 of the Senate (Representation of Territories) Act 1973. Retrieved August 2010.

- ^ Question without Notice: Loan Council Arrangements House Hansard,

- ^ Lijphart A., 'Australian Democracy: Modifying Majoritarianism?', Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 34, No. 3, 1999, pp 313–326

- ^ Sawer, Marian (1999). Overview: Institutional Design and the Role of the Senate (PDF). Representation and Institutional Change: 50 Years of Proportional Representation in the Senate. Vol. 34. pp. 1–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2011.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "53 Powers of the Houses in respect of legislation". Constitution of Australia. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Ted Morton, 'Senate Envy: Why Western Canada Wants What Australia Has' Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Senate Envy and Other Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series, 2001–2002, Department of the Senate, Canberra.

- ^ "Parliament of Australia: Senate: Statistics". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011.

- ^ "Senate weekly routine of business". Australian Senate. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- ^ Australian Senate, 'The Senate and Legislation' Archived 24 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Senate Brief, No. 8, 2008, Department of the Senate, Canberra.

- ^ Australian Senate, 'Consideration of legislation', Brief Guides to Senate Procedure, No. 9, Department of the Senate, Canberra.

- ^ "Media Release 43/2006 – Senate remains robust under Government majority". 30 June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Senator Chris Evans, The tyranny of the majority (speech)". 10 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 November 2009.

Labor has accused the Government of 'ramming' bills through the Senate – but Labor "guillotined" Parliamentary debate more than twice the number of times in their 13 years in Government than the Coalition has over the last decade. In the last six months, the Government has not sought to guillotine any bill through the Senate.

- ^ "Senator Andrew Murray: Australian Democrats Accountability Spokesperson Senate Statistics 1 July 2005 – 30 June 2006" (PDF). 4 July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2006.

- ^ Senate Standing Orders, numbers 7, 10, 98–105, 163

- ^ Deirdre McKeown, Rob Lundie and Greg Baker, 'Crossing the floor in the Federal Parliament 1950 – August 2004' Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Research Note, No. 11, 2005–06, Department of Parliamentary Services, Canberra.

- ^ Uhr, John (June 2005). "How Democratic is Parliament? A case study in auditing the performance of Parliaments" (PDF). Democratic Audit of Australia, Discussion Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Peter Veness, 'Crossing floor 'courageous, futile'[permanent dead link], news.com.au, 15 June 2006. Retrieved January 2008.

- ^ Neither of these instances resulted in the defeat of a government proposal, as in both cases Senator Steve Fielding voted with the government.

- ^ Prime Minister's press conference, 14 August 2006 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Nationals won't toe Libs' line: Joyce – SMH 18/9/2008". News.smh.com.au. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

Further reading

- Stanley Bach, Platypus and Parliament: The Australian Senate in Theory and Practice, Department of the Senate, 2003.

- Harry Evans, Odgers' Australian Senate Practice, A detailed reference work on all aspects of the Senate's powers, procedures and practices.

- John Halligan, Robin Miller and John Power, Parliament in the Twenty-first Century: Institutional Reform and Emerging Roles, Melbourne University Publishing, 2007.

- Wilfried Swenden, Federalism and Second Chambers: Regional Representation in Parliamentary Federations: the Australian Senate and German Bundesrat Compared, P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2004.

- John Uhr, The Senate and Proportional Representation: Public policy justifications of minority representation[permanent dead link], Working Paper no. 69, Graduate Program in Public Policy, Australian National University, 1999.