Trenton, New Jersey

City of Trenton, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Downtown Trenton, viewed from Morrisville, Pennsylvania | |

| Nickname(s): Capitol City, Turning Point of the Revolution. | |

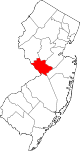

| Location of Trenton inside of Mercer County. Inset: Location of Mercer County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. Location of Trenton inside of Mercer County. Inset: Location of Mercer County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. | |

| Country | United States |

| County | Mercer |

| Incorporated | November 13, 1792 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| • Mayor | Douglas H. Palmer |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.1 sq mi (21.1 km2) |

| • Land | 7.6 sq mi (19.8 km2) |

| • Water | 0.5 sq mi (1.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 52 ft (16 m) |

| Population (2007)[2] | |

| • Total | 82,804 |

| • Density | 11,153.6/sq mi (4,304.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 08608, 08609, 08610, 08611, 08618, 08619, 08620, 08625, 08628, 08629, 08638, 08641, 08648, 08650 |

| Area code | 609 |

| FIPS code | 34-74000Template:GR[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0884540Template:GR |

| Website | www.trentonnj.org |

Trenton is the capital of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. As of 2007, the United States Census Bureau estimated that the city of Trenton had a population of 82,804.[2]

Trenton dates back at least to June 3, 1719, when mention was made of a constable being appointed for Trenton, while the area was still part of Hunterdon County. Boundaries were recorded for Trenton Township as of June 3, 1719. Trenton became New Jersey's capital as of November 25, 1790, and the City of Trenton was formed within Trenton Township on November 13, 1792. Trenton Township was incorporated as one of New Jersey's initial group of 104 townships by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 21, 1798. Portions of the township were taken on February 22, 1834, to form Ewing Township. A series of annexations took place over a fifty-year period, with the city absorbing South Trenton borough (April 14, 1851), portions of Nottingham Township (April 14, 1856), Chambersburg and Millham Township (both on March 30, 1888) and Wilbur borough (February 28, 1898).[4]

History

The first settlement which would become Trenton was established by Quakers in 1679, in the region then called the Falls of the Delaware, led by Mahlon Stacy from Handsworth, Sheffield, UK. Quakers were being persecuted in England at this time and North America provided the perfect opportunity to exercise their religious freedom.

By 1719, the town adopted the name "Trent-towne", after William Trent, one of its leading landholders who purchased much of the surrounding land from Stacy's family. This name later was shortened to "Trenton".

During the American Revolutionary War, the city was the site of George Washington's first military victory. On December 26, 1776, Washington and his army, after crossing the icy Delaware River to Trenton, defeated the Hessian troops garrisoned there (see Battle of Trenton). After the war, Trenton was briefly the national capital of the United States in November and December of 1784. The city was considered as a permanent capital for the new country, but the southern states favored a location south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Trenton became the state capital in 1790, but prior to that year the Legislature often met here. The town was incorporated in 1792.

During the 1812 War, the primary hospital facility for the U.S. Army was at a temporary location on Broad Street.

Throughout the 19th Century, Trenton grew steadily, as Europeans came to work in its pottery and wire rope mills. In 1837, with the population now too large for government by council, a new mayoral government was adopted, with by-laws that remain in operation to this day.

Geography

Trenton is located at 40°13′18″N 74°45′22″W / 40.221741°N 74.756138°W.Template:GR

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.1 square miles (21.1 km²)—7.7 square miles (19.8 km²) of it is land and 0.5 square miles (1.3 km²) of it is water. The total area is 6.01% water.

Several bridges across the Delaware River — the Trenton-Morrisville Toll Bridge, Lower Trenton Bridge and Calhoun Street Bridge - connect Trenton to Morrisville, Pennsylvania.

Several bridges across the Delaware River — the Trenton-Morrisville Toll Bridge, Lower Trenton Bridge and Calhoun Street Bridge - all of which connect Trenton to Morrisville, PA.

Trenton is located in almost the exact geographic center of the state (the official geographic center is 5 miles southeast of Trenton [2]). Due to this, it is sometimes included as part of North Jersey and as the southernmost city of the Tri-State Region. Others consider it a part of South Jersey and thus, the northernmost city of the Delaware Valley. Following the 2000 U.S. Census, Trenton was shifted from the Philadelphia metropolitan area to the New York metropolitan area.[3] However, Mercer County constitutes its own metropolitan statistical area, formally known as the Trenton-Ewing MSA.[4] Locals consider Trenton to be a part of ambiguous Central Jersey, and thus part of neither region. These same locals are generally split as to whether they are within New York or Philadelphia's sphere of influence.

Trenton is one of two state capitals that border another state - the other being Carson City, NV.

Climate

According to Koppen climate classification, Trenton enjoys a humid subtropical temperate climate with some marine influence due to the nearby Atlantic Ocean. The four seasons are of approximately equal length, with precipitation fairly evenly distributed through the year. The temperature is rarely below zero or above 100 °F.

During the winter months, temperatures routinely fall below freezing, but rarely fall below 0 °F. The coldest temperature ever recorded in Trenton was -14 °F (-25.6 °C) on February 9, 1934. The average January low is 24 °F (-4.4 °C) and the average January high is 38 °F (3.3 °C). The summers are usually very warm, with temperatures often reaching into the 90 °F's, but rarely reaching into the 100 °F's. The average July low is 67 °F (19.4 °C) and the average July high is 85 °F (29.4 °C). The temperature reaches or exceeds 90 °F on 18 days each year, on average. The hottest temperature ever recorded in Trenton was 106 °F (41.1 °C) on July 9, 1936.

The average precipitation is 45.77 inches (1,163.1 mm) per year, which is fairly evenly distributed through the year. The driest month on average is February, with only 2.87 inches (72.9 mm) of rainfall on average, while the wettest month is July, with 4.82 inches (122.4 mm) of rainfall on average. Rainfall extremes can occur, however. The all-time single-day rainfall record is 7.25 inches (184.1 mm) on September 16, 1999, during the passage of Hurricane Floyd. The all-time monthly rainfall record is 14.55 inches (369.6 mm) in August 1955, due to the passage of Hurricane Connie and Hurricane Diane. The wettest year on record was 1996, when 67.90 inches (1,720 mm) of rain fell. On the flip side, the driest month on record was October 1963, when only 0.05 inches (1.27 mm) of rain was recorded. The driest year on record was 1957, when only 28.79 inches (731.27 mm) of rain was recorded.

Snowfall can vary even more year-to-year. The average snowfall is 23.4 inches, but has ranged from as low as 2 inches (in the winter of 1918-19) to as high as 76.9 inches (in 1995-96). The heaviest snowstorm on record was the Blizzard of 1996 on January 7-8, 1996, when 24.2 inches of snow fell.

| Climate data for Carteret, New Jersey | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: Source: NCDC | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 3,002 | — | |

| 1820 | 3,942 | 31.3% | |

| 1830 | 3,925 | −0.4% | |

| 1840 | 4,035 | 2.8% | |

| 1850 | 6,461 | 60.1% | |

| 1860 | 17,228 | 166.6% | |

| 1870 | 22,874 | 32.8% | |

| 1880 | 29,910 | 30.8% | |

| 1890 | 57,458 | 92.1% | |

| 1900 | 73,307 | 27.6% | |

| 1910 | 96,815 | 32.1% | |

| 1920 | 119,289 | 23.2% | |

| 1930 | 123,356 | 3.4% | |

| 1940 | 124,697 | 1.1% | |

| 1950 | 128,009 | 2.7% | |

| 1960 | 114,167 | −10.8% | |

| 1970 | 104,638 | −8.3% | |

| 1980 | 92,124 | −12.0% | |

| 1990 | 88,675 | −3.7% | |

| 2000 | 85,403 | −3.7% | |

| 2008 United States Census Bureau. Accessed August 1, 2007.</ref> (est.) | 86,864 | [2] | Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[". |

| historical data sources:[5][6][7] | |||

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 85,403, people, 29,437 households, and 18,692 families residing in the city. The population density was 11,153.6 people per square mile (4,304.7/km² ). There were 33,843 housing units at an average density of 4,419.9 per square mile (1,705.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 52.06% African American, 32.55% White, 0.35% Native American, 0.84% Asian, 0.23% Pacific Islander, 10.76% from other races, and 3.20% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 21.53% of the population. Non-Hispanic whites made up 24.62% of the population.

There were 29,437 households, 32.4% of which had children under the age of 18 living with them. 29.0% were married couples living together, 27.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.5% were non-families. 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.75 and the average family size was 3.38.

In the city the population was spread out with 27.7% under the age of 18, 10.1% from 18 to 24, 31.9% from 25 to 44, 18.9% from 45 to 64, and 11.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 97.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,074, and the median income for a family was $36,681. Males had a median income of $29,721 versus $26,943 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,621. About 17.6% of families and 21.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.8% of those under age 18 and 19.5% of those age 65 or over.

Top 10 ethnicities reported during the 2000 Census by percentage

- African American (52.1)

- Puerto Rican (10.5)

- Italian (7.3)

- Irish (4.5)

- Polish (3.8)

- Guatemala (3.1)

- English (2.0)

- Jamaican (1.3)

- Hungarian (1.1)

- Mexican (1.1)

Economy

Trenton was a major manufacturing center in the late 1800s and early 1900s. One relic of that era is the slogan "Trenton Makes, The World Takes", which is displayed on the Lower Free Bridge (just north of the Trenton–Morrisville Toll Bridge). The city adopted the slogan in 1917 to represent Trenton's then-leading role as a major manufacturing center for rubber, wire rope, ceramics and cigars. [5].

Along with many other United States cities in the 1960s and 1970s, Trenton fell on hard times when manufacturing and industrial jobs declined. Concurrently, state government agencies began leasing office space in the surrounding suburbs. State government leaders (particularly governors William Cahill and Brendan Byrne) attempted to revitalize the downtown area by making it the center of state government. Between 1982 and 1992, more than a dozen office buildings were constructed primarily by the state to house state offices. [6] Today, Trenton's biggest employer is still the state of New Jersey. Each weekday, 20,000 state workers flood into the city from the surrounding suburbs. [7]

In the early 1970s, then Mayor Art Holland spearheaded an effort to close State Street between Montgomery and Warren Street (the center of the downtown business district). The intention was to lure big department stores, such as J.C. Penney and Montgomery Ward to the downtown area to anchor an urban shopping district. The pedestrian mall, named the Trenton Commons, was officially opened in September 1973. By all accounts, the experiment flopped. The Commons did nothing lure new businesses to the downtown area or stem the flow of longtime downtown merchants' (most notably Sears and Dunham’s) exodus to the suburbs. Additionally, the Commons created a complicated downtown traffic pattern which made navigating the surrounding area a nightmare. Furthermore, the plan failed to address the lack of parking and crime and safety issues. Lastly, the poor design of the mall, which consisted of harsh metal pipes covered by glasslike canopies and accented by concrete bollards contrasted with Trenton’s historic architecture [8]. In 2004, the Trenton Commons experiment finally ended, as vehicular access was fully restored to State Street between Montgomery and Warren Street. The closure of State Street by Mayor Holland, coupled with his tacit approval of the demolition of the Capitol and Lincoln Theaters (both former historical opera houses) in favor of parking lots, effectively prevented any future development of Trenton as a center of culture. Ironically, Mayor Holland worked for the preservation of an insignificant brick warehouse near the former Sears building for use as an art center. Other failed projects under the Holland administration included his attempted purchase and relocation of an arena located in Cherry Hill to replace the Trenton Civic Center (formerly the Trenton Armory) which had been destroyed by fire.

Urban Enterprise Zone

Portions of Trenton are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3½% sales tax rate (versus the 7% rate charged statewide).[8]

Neighborhoods

The city of Trenton is home to numerous neighborhoods and sub-neighborhoods. The main neighborhoods are taken from the four cardinal directions (North, South, East, and West). Trenton was once home to large Italian, Hungarian, and Jewish communities, but since the 1960s demographic shifts have changed the city into a relatively segregated urban enclave of poorer African Americans. Italians are scattered throughout the city, but a distinct Italian community is centered in the Chambersburg neighborhood, in South Trenton. This community has been in decline since the 1970s, largely due to economic and social shifts to the more prosperous, less crime-ridden suburbs surrounding the city. Today Chambersburg has a large Latino community. Many of the Latino immigrants are from Guatemala, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Nicaragua. The Latino community once had a heavy concentration of Puerto Ricans, but more recent Central and South American immigrants have changed that.[citation needed]

The North Ward, once a mecca for the city's middle class, is now one of the most economically distressed, torn apart by race riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968. Nonetheless, the area still retains many important architectural and historic sites. North Trenton has a large Polish-American neighborhood that borders Lawrence Township, many of whom attend St Hedwigs Roman Catholic Church on Brunswick Ave. St. Hedwigs church was built in 1904 by Polish immigrants,many of whose families still attend the church. North Trenton is also home to the historic Shiloh Baptist Church—one of the largest houses of worship in Trenton and the oldest African American church in the city founded in 1888. The church is currently pastored by Rev. Darrell L. Armstrong who carried the Olympic torch in 2002 for the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. Also located just at the southern tip of North Trenton is the city's Battle Monument, also known as "Five Points". It is a 150 ft. structure that marks the spot where George Washington's Continental Army launched the Battle of Trenton during the American Revolutionary War. It faces downtown Trenton and is a symbol of the city's historic past.

South Ward is the most diverse neighborhood in Trenton and is home to many Latin American, Italian-American, and African American residents.

East Ward is the smallest neighborhood in Trenton and is home to the Trenton's Train Station as well as Trenton Central High School. Recently, two campuses have been added, Trenton Central High School West and Trenton Central High School North, respectively, in those areas of the city. The Chambersburg neighborhood is within the East Ward, and was once noted in the region as a destination for its many Italian restaurants and pizzerias. With changing demographics, some of these businesses have either closed or relocated to suburban locations.

West Ward is the home of Trenton's more suburban neighborhoods, including Hiltonia, Glen Afton, Berkeley Square, and the area surrounding Cadwalader Park.

In addition to these neighborhoods, other notable sections include the "The Island" (a small neighborhood between Route 29 and the Delaware River and historic Mill Hill located next door to downtown Trenton. Kingsbury Towers (a high rise apartment complex technically in South Ward) is also semi-autonomous or neutral. the Fisher-Richey-Perdicaris neighborhood comprises a little-known district sandwiched between West State Street and Route 29 with large several-story residences dating from ca. 1915.

Government

Local government

The City of Trenton is governed under the Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) system of municipal government.[9]

Trenton's current Mayor, Douglas Palmer, has been in office since July 1, 1990. Douglas Palmer is the first African American to become Mayor in the City of Trenton. Among holding the position of Mayor, Douglas Palmer was also named President of the United States Conference of Mayors in December 2006.[10]

Members of the City Council are:[11]

- Paul M. Pintella - Council President and Councilman At Large

- Annette H. Lartigue - Council Vice President and West Ward Councilwoman

- Milford Bethea - North Ward Councilman

- James H. Coston - South Ward Councilman

- Gino A. Melone - East Ward Councilman

- Manuel Segura - Councilman At Large

- Cordelia M. Staton - Councilwoman At Large

Federal, state and county representation

Trenton is spread across two congressional districts, the Fourth Congressional District and the Twelfth Congressional District, and is part of New Jersey's 15th Legislative District.[12]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 4th congressional district is represented by Chris Smith (R, Manchester Township).[13][14] For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 12th congressional district is represented by Bonnie Watson Coleman (D, Ewing Township).[15][16] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[17] and George Helmy (Mountain Lakes, term ends 2024).[18][19]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 15th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Shirley Turner (D, Lawrence Township) and in the General Assembly by Verlina Reynolds-Jackson (D, Trenton) and Anthony Verrelli (D, Hopewell Township).[20] Template:NJ Governor

Mercer County is governed by a County Executive who oversees the day-to-day operations of the county and by a seven-member Board of County Commissioners that acts in a legislative capacity, setting policy. All officials are chosen at-large in partisan elections, with the executive serving a four-year term of office while the commissioners serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats up for election each year as part of the November general election.[21] As of 2024[update], the County Executive is Daniel R. Benson (D, Hamilton Township) whose term of office ends December 31, 2027.[22] Mercer County's Commissioners are:

Lucylle R. S. Walter (D, Ewing Township, 2026),[23] Chair John A. Cimino (D, Hamilton Township, 2026),[24] Samuel T. Frisby Sr. (D, Trenton, 2024),[25] Cathleen M. Lewis (D, Lawrence Township, 2025),[26] Vice Chair Kristin L. McLaughlin (D, Hopewell Township, 2024),[27] Nina D. Melker (D, Hamilton Township, 2025)[28] and Terrance Stokes (D, Ewing Township, 2024).[29][30][31]

Mercer County's constitutional officers are: Clerk Paula Sollami-Covello (D, Lawrence Township, 2025),[32][33] Sheriff John A. Kemler (D, Hamilton Township, 2026)[34][35] and Surrogate Diane Gerofsky (D, Lawrence Township, 2026).[36][37][38]

Education

Colleges and universities

Trenton is the home of two post-secondary institutions, Thomas Edison State College and Mercer County Community College's James Kearney Campus. The College of New Jersey, formerly named Trenton State College, was founded in Trenton in 1855 and is now located in nearby Ewing Township. Rider University was founded in Trenton in 1865 as The Trenton Business College. In 1964, Rider moved to its current location in nearby Lawrence Township. [9]

Public schools

The Trenton Public Schools serve students in kindergarten through twelfth grade. The district is one of 31 Abbott Districts statewide.[39] The Superintendent runs the district and the school board is appointed by the Mayor. The School District has undergone a 'construction' renaissance throughout the district. Trenton Central High School is Trenton's only traditional public high school.

Charter schools

Trenton is home to many charter schools, Capital Preparatory Charter High School, Emily Fisher Charter School, Foundation Academy Charter School, International Charter School, Paul Robeson Charter School, Trenton Community Charter School, and Village Charter School.[40]

Other schools

Trenton Community Music School is a not-for-profit community school of the arts. The school was founded by executive director Marcia Wood in 1997.

Crime

In 2005, there were 31 homicides in Trenton, the largest number in a single year in the city's history, with 22 of the homicides believed to be gang related.[41] The city was named the 4th "Most Dangerous" in 2005 out of 129 cities with a population of 75,000 to 99,999 ranked nationwide.[42] In the 2006 survey, Trenton was ranked as the 14th most dangerous "city" overall out of 371 cities included nationwide in the 13th annual Morgan Quitno survey, and was again named as the fourth most dangerous "city" of 126 cities in the 75,000-99,999 population range.[43] Homicides went down in 2006 to 20, but back up to 25 in 2007[44] As of October 9, 2008 there have been 18 homicides in Trenton.

Trenton's mayor, Douglas Palmer, is a member of the Mayors Against Illegal Guns Coalition,[45] a bi-partisan group with a stated goal of "making the public safer by getting illegal guns off the streets." The coalition is co-chaired by Boston Mayor Thomas Menino and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Riots of 1968

Many[who?] today mark the '68 riots as the last time Trenton was a commercial and residential hub. Historian Charles Webster puts it simply: "The riots that killed Trenton."

The Trenton Riots of 1968 were a major civil disturbance that took place during the week following the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King in Memphis on April 4. Race riots broke out nationwide following the murder of the civil rights activist.

More than 200 Trenton businesses mostly in Downtown, were ransacked and burned.

More than 300 people, most of them young black men, were arrested on charges ranging from assault and arson to looting and violating the mayor's emergency curfew. Most of the assaults were on ill prepared policemen with outdated equipment, including one nearly killed when run over by a truck.

In addition to 16 other injured policemen, 15 firefighters were treated at city hospitals for smoke inhalation, burns, sprains and cuts suffered while fighting raging blazes or for injuries inflicted by rioters. Denizens of Trenton urban core often pulled false alarms and would then throw bricks at firefighters responding to the alarm boxes. This experience, along with similar experiences in other major cities, effectively ended the use of open-cab fire engines. As an interim measure, the Trenton Fire Department fabricated temporary cab enclosures from steel deck plating until new equipment could be obtained. The losses incurred by downtown businesses were estimated at $17 million.[46]

Trenton's Battle Monument neighborhood was hardest hit. Since the 1950s, North Trenton had witnessed a steady exodus of middle-class residents, and the riots spelled the end for North Trenton. By the 1970s, the region had become one of the most blighted and crime-ridden in the city, although gentrification in the area is revitalizing certain sections.

New Jersey State Prison

The New Jersey State Prison (formerly Trenton State Prison), which has two maximum security units, is located in Trenton. The prison houses some of the state's most dangerous individuals, which included New Jersey's Death Row population until the state banned capital punishment in 2007.

The following inscribed over the original entrance to the prison.

Labor, Silence, Penitence. The Penitentiary House, Erected By Legislative Authority. Richard Howell, Governor. In The XXII Year Of American Independence MDCCXCVII That Those Who Are Feared For Their Crimes May Learn To Fear The Laws And Be Useful Hic Labor, Hic Opus.[47]

Transportation

City highways include the Trenton Freeway, which is part of U.S. Route 1, and the John Fitch Parkway, which is part of Route 29. Canal Boulevard, more commonly known as Route 129, connects US Route 1 and NJ Route 29 in South Trenton. U.S. Route 206, Route 31, and Route 33 also pass through the city via regular city streets (Broad Street/Brunswick Avenue/Princeton Avenue, Pennington Avenue, and Greenwood Avenue, respectively). Interstate 195 connects the city to Interstate 295 and the New Jersey Turnpike (also known as Interstate 95) via NJ Routes 29 and 129. The Pennsylvania Turnpike (I-276) also passes close to the city.

Public transportation within the city and to/from its nearby suburbs is provided in the form of local bus routes run by New Jersey Transit. SEPTA also provides bus service to adjacent Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

The Trenton Train Station, located on the heavily traveled Northeast Corridor, serves as the northbound terminus for SEPTA's R7 Trenton line (local train service to Philadelphia) and southbound terminus for New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor Line (local train service to New York). The train station also serves as the northbound terminus for the River Line; a diesel light rail line that runs to Camden. Two additional River Line stops, Cass Street and Hamilton Avenue, are located within the city.

Long-distance transportation is provided by Amtrak train service along the Northeast Corridor. Limited commercial airline transportation is provided at nearby Trenton-Mercer Airport in Ewing. Much more extensive airline service is available at the more distant international airports in Newark (reachable by direct New Jersey Transit or Amtrak rail link) and Philadelphia.

Media

Trenton is served by The Times, and the Trentonian. Radio station WKXW is also licensed to Trenton.

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Affiliate | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trenton Thunder | EL, Baseball | Mercer County Waterfront Park | New York Yankees | 1994 | 2 |

| Trenton Devils | ECHL, Ice hockey | Sun National Bank Center | New Jersey Devils | 1999 | 1 |

| Trenton Steel | AIFA, Indoor football | Sun National Bank Center | N/A | 2010 | 0 |

Because of Trenton's relative distance to New York City and Philadelphia, and because most homes in Mercer County receive network broadcasts from both cities, locals are sharply divided fan loyalty to both cities. It is not uncommon to find fans of Philadelphia's Phillies, Eagles, 76ers, and Flyers cheering (and arguing) right along side New York Yankees, Mets, Nets, Knicks, Devils, Rangers, Jets, and Giants fans.

Between 1948 and 1979 Trenton Speedway hosted world class auto racing. It was actually located in adjacent Hamilton Township. Famous drivers such as Jim Clark, A. J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Al Unser, Bobby Unser, Richard Petty and Bobby Allison raced on the one mile asphalt oval and then re-configured 1 1/2 mile race track. The speedway, which closed in 1980, was part of the larger New Jersey State Fairgrounds complex, which also closed in 1983. The former site of the speedway and fairgrounds is now the Grounds for Sculpture.

Points of interest

- Cadwalader Park - city park designed by noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted[10]. Olmsted is most famous for designing New York City's Central Park.

- Friends Burying Ground

- New Jersey State House

- New Jersey State Library

- New Jersey State Museum

- Old Barracks - last remaining colonial barracks in the country.

- William Trent House

Trivia

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (August 2009) |

- Trenton is one of the only two state capitals which border another state. The other such capital is Carson City, Nevada, which borders California. Alaska's capital city, Juneau, borders British Columbia, Canada.

- Trenton is an American city to have been the capital of all four forms of secular government: municipal, county, state, and country. New York City and Philadelphia have also filled these roles however they have not been state capitals since the 18th century.

- In 1896, the first professional basketball game was played in Trenton between the Trentons and the Brooklyn YMCA.[48]

- Pork roll (often referred to as Taylor ham outside the Trenton area [49]) was invented in Trenton in 1856 by 19th century New Jersey Politician and Trenton native John Taylor.

- The tomato pie was first sold at Joe's Tomato Pies in Chambersburg in 1910[50], and Papa's Tomato Pies in 1912.[50]

- In 1992, then Vice President Dan Quayle infamously misspelled the word 'potato' at a spelling bee in Trenton.

- The Fugees' cover of the Bob Marley song "No Woman, No Cry" mentions both "Jersey" and "Trenchtown" in different verses, unintentionally leading some people to erroneously believe that Trenchtown is a nickname for Trenton.

- Trenton is famous for the sign on the lower bridge crossing the Delaware -- "Trenton Makes, the World Takes," a slogan created by local business interests in the early part of the 20th Century when Trenton was a thriving industrial city with major pottery, ceramics, steel, and other heavy manufacturing interests. The bridge has been seen in many motion pictures in recent years, including Stealing Home.

- Trenton is the location for the Stephanie Plum novels by Janet Evanovich.

- In 1873, eighteen out of the twenty-four pottery companies in the United States were in Trenton.[51]

Noted residents

Some well-known Americans who were born and/or have lived in Trenton include:

- Roxanne Hart (born July 27, 1952) Actress-Highlander, Chicago Hope

- Anthony Maddox raised and graduated from Trenton Central Highschool. Co-founder of MadVision Entertainment, and executive producer of their production division. Previously he created MADMAN Entertainment. Currently MadVision Entertainment has the rights to Soul Train, and will be re-launching it.

- George Antheil (1900-1959), pianist, composer, writer, inventor

- Henry W. Antheil, Jr. (1912-1940), diplomatic code clerk, honored for service to United States

- Samuel Alito (born 1950), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

- New Atlantic, alternative rock band

- Bo Belinsky (1936-2001), former professional baseball player

- Elvin Bethea (1936-), Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive end who played his entire NFL career with the Houston Oilers.[52]

- John T. Bird (1829-1911), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district from 1869 to 1873.[53]

- James Bishop (1816-1895), represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1855-1857.[54]

- Edward Bloor (born 1950), novelist

- Steve Braun (born 1948), former professional baseball player

- Betty Bronson (1907-1971), actress

- J. Hart Brewer (1844-1900), represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district from 1881 to 1885.[55]

- James Buchanan (1839-1900) represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district from 1885 to 1893.[56]

- Shawn Corey Carter (born 1969, a.k.a. Jay Z), rap mogul, CEO

- George Case (1915-1989), former outfielder for the Washington Senators.

- Terrance Cauthen (born 1976), lightweight boxer who won a bronze medal at the 1996 Summer Olympics.[57]

- Richie Cole, jazz alto saxophonist

- Richard Crooks, tenor and a leading singer at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

- David Dinkins (born 1927), first black mayor of New York City.[58]

- Al Downing (born 1941), former professional baseball player

- Greg Forester (born 1982), noted reporter, blogger, activist

- Samuel Gibbs French, Major General in the Confederate States Army.[59]

- Dave Gallagher (born 1960), former professional baseball player

- Greg Grant, former NBA player

- Tom Guiry (born 1981), actor

- Roy Hinson former professional basketball player.

- Charles R. Howell (1904-1973), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1955.[60]

- Elijah C. Hutchinson (1855-1932), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district from 1915–1923.[61]

- William J. Johnston (1918-1990), Medal of Honor recipient for gallantry during World War II.[62]

- Dahntay Jones (born 1980), professional basketball player

- Nicholas Katzenbach (born 1922), United States Attorney General in the Johnson Administration.

- Patrick Kerney (born 1976), professional football player

- Tad Kornegay (born 1982) defensive back for the Saskatchewan Roughriders in the Canadian Football League.[63]

- Ernie Kovacs (1919-1962), comedian

- Judith Light (born 1949), actress

- Amy Locane (born 1971), actress

- Nia Long (born 1970), actress

- Craig Mack (born 1971), rapper

- Kareem McKenzie (born 1979), offensive tackle for the New York Giants of the National Football League, born in Trenton

- N. Gregory Mankiw (born 1958), macroeconomist.[64]

- Zebulon Pike (1779-1813), explorer and namesake of Pikes Peak.[65]

- D. Lane Powers (1896-1968), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1933 to 1945.[66]

- Poor Righteous Teachers, hip-hop group

- Amy Robinson (born 1948), actress and film producer

- Dennis Rodman (born 1961), former professional basketball star

- Bob Ryan (born 1946), sportswriter, regular contributor on the ESPN show Around the Horn

- Daniel Bailey Ryall (1798-1864), United States Representative from New Jersey, in office from 1839-1841.[67]

- Antonin Scalia (born 1936), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.[68]

- Frank D. Schroth (1884-1974), owner of the Brooklyn Eagle, who had earlier worked as a reporter at The Times[69]

- Thomas N. Schroth (1921-2009), editor of Congressional Quarterly and founder of The National Journal.[70]

- Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr. (born 1934), Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Central Command in the Gulf War

- Charles Skelton (1806-1879), represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1851 to 1855.[71]

- Sommore (born 1967), comedian

- Robert Stempel (born 1933), former chairman and CEO of General Motors.

- Gary Stills (born 1974), professional football player

- Mike Tiernan (1867-1918), major league baseball player[72]

- Ty Treadway (born 1967), host of Merv Griffin's Crosswords.[73]

- Troy Vincent (born 1971), professional American football player, former president of the NFL Players Association

- Allan B. Walsh (1874-1953), represented the 4th congressional district from 1913 to 1915.[74]

- Charlie Weis (born 1956), Notre Dame football coach.[75]

- Chill Billiawn (born 1988), rapper born in Trenton

- Ira W. Wood (1856-1931), represented New Jersey's 4th congressional district from 1904 to 1913.[76]

References

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: City of Trenton, Geographic Names Information System, accessed June 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFPopulation?_event=Search&geo_id=06000US3402160915&_geoContext=01000US%

- ^ A Cure for the Common Codes: New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed July 14, 2008.

- ^ "The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968", John P. Snyder, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 164.

- ^ "New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930 - 1990". Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Campbell Gibson (June 1998). "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States: 1790 TO 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ Wm. C. Hunt, Chief Statistician for Population. "Fourteenth Census of The United States: 1920; Population: New Jersey; Number of inhabitants, by counties and minor civil divisions" (ZIP). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ Geographic & Urban Redevelopment Tax Credit Programs: Urban Enterprise Zone Employee Tax Credit, State of New Jersey. Accessed July 28, 2008.

- ^ 2005 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, April 2005, p. 73.

- ^ Biography of Mayor Douglas Palmer, City of Trenton. Accessed June 10, 2007.

- ^ Meet the City Council, City of Trenton. Accessed June 10, 2007.

- ^ 2008 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government, New Jersey League of Women Voters, p. 65. Accessed September 30, 2009.

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed August 5, 2022.

- ^ Fox, Joey. "Who is N.J.’s most bipartisan member of Congress, really?", New Jersey Globe, July 28, 2022. Accessed March 21, 2023. "As for Republicans, Rep. Chris Smith (R-Manchester) voted with Biden 37% of the time, "

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ Biography, Congresswoman Bonnie Watson Coleman. Accessed January 3, 2019. "Watson Coleman and her husband William reside in Ewing Township and are blessed to have three sons; William, Troy, and Jared and three grandchildren; William, Kamryn and Ashanee."

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/23/nyregion/george-helmy-bob-menendez-murphy.html

- ^ Tully, Tracey (August 23, 2024). "Menendez's Senate Replacement Has Been a Democrat for Just 5 Months". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 15, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 18, 2024.

- ^ Government, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023. "Mercer County is governed by an elected County Executive and a seven-member Freeholder Board."

- ^ Meet the County Executive, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023. "Brian M. Hughes continues to build upon a family legacy of public service as the fourth person to serve as Mercer County Executive. The voters have reaffirmed their support for Brian's leadership by re-electing him three times since they first placed him in office in November 2003."

- ^ Lucylle R. S. Walter, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ John A. Cimino, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Samuel T. Frisby Sr., Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Cathleen M. Lewis, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Kristin L. McLaughlin, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Nina D. Melker, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Terrance Stokes, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Meet the Commissioners, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ 2022 County Data Sheet, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Meet the Clerk, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Members List: Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Meet the Sheriff, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Members List: Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Meet the Surrogate, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Members List: Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Elected Officials for Mercer County, Mercer County. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Abbott Districts, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed March 31, 2008.

- ^ "Charter Schools Directory". State of New Jersey Department of Education. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ Trenton murders hit all-time high, Signal, January 25, 2006.

- ^ 12th Annual Safest/Most Dangerous Cities Survey: Top and Bottom 25 Cities Overall, accessed June 23, 2006

- ^ 13th Annual Safest (and Most Dangerous) Cities: Top and Bottom 25 Cities Overall, Morgan Quitno. Accessed October 30, 2006.

- ^ Shea, Kevin. "City sees murder rate increase: Trenton records 25 homicides in 2007, up from 20 in 2006", The Times (Trenton), January 2, 2008. Accessed January 21, 2008. "Trenton had 25 homicides in 2007, up from 20 in 2006."

- ^ "Mayors Against Illegal Guns: Coalition Members".

- ^ http://www.capitalcentury.com/1968.html, accessed February 27, 2007

- ^ http://www.windsorpress.net/io_hotp.html

- ^ http://www.capitalcentury.com/1900.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b http://slice.seriouseats.com/archives/2006/02/a_slice_of_heaven_american_pizza_timeline.html

- ^ "Trenton's Potteries". The New York Times. March 29, 1873.

- ^ Elvin Bethea, database Football. Accessed November 26, 2007.

- ^ John Taylor Bird, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed August 17, 2007.

- ^ James Bishop, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 1, 2007.

- ^ John Hart Brewer, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed August 17, 2007.

- ^ James Buchanan, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed August 27, 2007.

- ^ Longman, Jere. "BOXING;3 Friends Qualify for U.S. Boxing Team", The New York Times, April 19, 1996. Accessed December 4, 2007. "Cauthen, 19, grew up 40 miles north, in Trenton, but he has fought out of Frazier's gym in Philadelphia for nine years."

- ^ Bohlen, Celestine. " THE NATION: David N. Dinkins; An Even Temper In the Tempest of Mayoral Politics", The New York Times, September 17, 1989. Accessed April 11, 2008. "From his childhood, which he spent divided between New York City and Trenton, David Dinkins has kept steady control of his emotions, friends and family members say. When he was 6 years old, his mother left his father in Trenton and moved to New York, taking her two children with her. Mr. Dinkins later returned to Trenton, where he attended elementary and high school."

- ^ Armstrong, Samuel S. "Trenton in the Mexican, Civil, and Spanish-American Wars", accessed May 9, 2007. "Samuel Gibbs French was a native of Trenton and graduated from West Point in 1843 with the brevet rank of Second Lieutenant and assigned to the Third U.S. Artillery, July 1, 1843."

- ^ Charles Robert Howell, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 10, 2007.

- ^ Elijah Cubberley Hutchinson, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients — World War II (G-L)". Medal of Honor Citations. U.S. Army Center of Military History. July 16, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ^ CFL.ca Player Profile. Accessed December 17, 2007.

- ^ Andres, Edmund L. "A Salesman for Bush's Tax Plan Who Has Belittled Similar Ideas", The New York Times, February 28, 2003.

- ^ Baldwin, Tom. "Where did Pike peak? Colo. explorer got start in New Jersey", Courier-Post, August 25, 2008. Accessed September 19, 2008. "Nineteenth century Jersey explorer Zebulon Pike was born in Lamberton, now a part of south Trenton, but gave his name to Colorado's 14,000-foot Pikes Peak."

- ^ David Lane Powers, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 9, 2007.

- ^ Daniel Bailey Ryall, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 3, 2007.

- ^ Staff. "ANTONIN SCALIA ASSOCIATE JUSTICE NOMINEE", The Miami Herald, June 18, 1986. Accessed August 6, 2009.

- ^ Staff. "Frank D. Schroth, 89, Publisher Of The Brooklyn Eagle, Is Dead; Acclaimed for His Service", The New York Times, June 11, 1974. Accessed August 6, 2009.

- ^ Weber, Bruce. "Thomas N. Schroth, Influential Washington Editor, Is Dead at 88", The New York Times, August 4, 2009. Accessed August 5, 2009.

- ^ Charles Skelton, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed August 25, 2007.

- ^ Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th edition ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-578970-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Host: Ty Treadway, Merv Griffin's Crosswords. Archived as of January 13, 2008. Accessed August 7, 2009.

- ^ Allan Bartholomew Walsh, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 6, 2007.

- ^ Charlie Weis, New England Patriots. Accessed August 18, 2007.

- ^ Ira Wells Wood, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed September 6, 2007.

Algernon Ward Jr, North Ward Activist

External links

- City of Trenton website

- Trenton local community news

- Trenton Public Schools

- School Performance Reports for the Trenton Public Schools, New Jersey Department of Education

- Data for the Trenton Public Schools, National Center for Education Statistics

- Trenton Historical Society

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Trenton, New Jersey

- US Census Data for Trenton, NJ

- Articles with trivia sections from August 2009

- Cities in New Jersey

- County seats in New Jersey

- Faulkner Act Mayor-Council

- Former capitals of the United States

- New Jersey Urban Enterprise Zones

- Trenton, New Jersey

- New Jersey Supreme Court

- United States communities with African American majority populations

- Settlements established in 1679

- Former townships in New Jersey

- State capitals in the United States