Chinese calendar

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

The traditional Chinese calendar (official Chinese name: Rural Calendar (農曆; 农历; Nónglì; 'farming calendar'),[a] alternately Former Calendar (舊曆; 旧历; Jiùlì), Traditional Calendar (老曆; 老历; Lǎolì), or Lunar Calendar (陰曆; 阴历; Yīnlì; 'yin calendar')) is a lunisolar calendar which reckons years, months and days according to astronomical phenomena. It was first developed during the Qin Dynasty[citation needed], and is currently defined by GB/T 33661-2017 Calculation and promulgation of the Chinese calendar, which the Standardization Administration of China issued on May 12, 2017.

China now officially uses the Gregorian calendar, but the traditional Chinese calendar still governs traditional activities in China and in overseas Chinese communities, such as the Chinese New Year. It lists the dates of traditional Chinese holidays, and guides people in selecting the most auspicious days for weddings, funerals, moving, or beginning a business.

As with Chinese characters, different variants of this calendar are used in different parts of the Chinese cultural sphere. Korea, Vietnam, and the Ryukyu Islands adopted the calendar completely, where it evolved into Korean, Vietnamese, and Ryukyuan calendars, respectively. The main difference from the traditional Chinese calendar is the use of different meridians, which leads to some astronomical events—and the calendar events based on those—falling on different dates. The traditional Japanese calendar also derived from the Chinese calendar based on a Japanese meridian, but its official use in Japan was abolished in 1873 as part of reforms subsequent to the Meiji Restoration. Calendars in Mongolia and Tibet have absorbed elements from the traditional Chinese calendar, but they are not direct descendants of it.

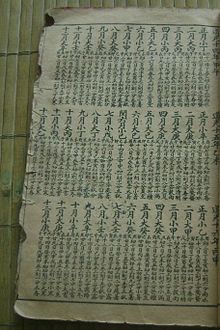

In this calendar, days begin and end at midnight. Months begin on the day with the new moon. Years begin on the second or third new moon after the winter solstice. The solar terms govern the start and end of each month. Written versions in ancient China[when?] would include information such as the stem-branch of the year and names of each month, including leap months when needed. For each month, there would be characters for whether the month was long (大, containing 30 days) or short (小, containing 29 days); the stem-branches for the first, eleventh, and 21st days; and the date, stem-branch, and time of the solar terms.

Structure

General

Definitions of elements in the traditional Chinese calendar:

- Day, the time from one midnight to the next.

- Month, the time from one new moon to the next. These synodic months are about 29 17⁄32 days long.

- Date, when a day occurs within the month. Days are numbered in sequence from 1 – 29 or 1 – 30.

- Year, the time of one full revolution of Earth around the sun. This is measured from the first day of spring (lunisolar year) or the winter solstice (solar year). A year is about 365 31⁄128 days.

- Zodiac, 1⁄12 year, 30° on the ecliptic. A zodiac is about 30 7⁄16 days. The Chinese zodiac is 45° away from the Western zodiac[citation needed].

- Solar term, 1⁄24 year, 15° on the ecliptic. A solar term is about 15 7⁄32 days.

- Calendar month, when a month occurs within the year. The months are numbered according to the zodiac number[citation needed] and some months may be repeated.

- Calendar year, when it is agreed that one year ends and another begins. In this calendar, the year starts on the first day of spring, defined as the day on which the second (sometimes third) dark moon after winter solstice falls. A calendar year is 353 – 355 days or 383 – 385 days long.

The Chinese calendar is lunisolar, similar to the Hindu and Hebrew calendars.

7 Luminaries, Great Bear (Ursa Major), 3 Enclosures, 28 Mansions

The movements of the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are the key references for calendar calculations. These are known as the seven luminaries.

- The distance between Mercury and the sun is within 30°, which is the sun's height at chénshí (辰時) or 08:00-10:00, so Mercury was sometimes called the "chen star" (辰星). More commonly, it is called the "water star" (水星).

- Venus appears at dawn and dusk, so the Venus is called the "bright star" (啟明星; 启明星) or "long star" (長庚星; 长庚星).

- Mars looks like fire and occurs irregularly, so Mars is called the "fire star" (熒惑星; 荧惑星 or 火星). Mars is in charge of punishment in Chinese culture. When Mars is close to Antares (心宿二), it is a sign of bad luck and can forebode the death of the emperor or the ousting of the chancellor (荧惑守心).

- The period of Jupiter's revolution is about 11.86 years, so Jupiter is called the "age star" (歲星; 岁星), since 30° of Jupiter's revolution is about a year on Earth.

- The period of Saturn's revolution is about 28 years, so Saturn is called the "guard star" (鎮星). This means that Saturn guards one of the 28 mansions every year.

The Big Dipper is regarded as the compass in the sky, and the handle's direction decides the season and solar month.

The stars are divided into Three Enclosures and 28 Mansions according to their locations in the sky relative to Ursa Minor at the centre. Each mansion is named with a character that describes the shape of the principal asterism it contains.

- Central (Three Enclosures): Purple Forbidden (紫微), Supreme Palace (太微), Heavenly Market (天市)

- Eastern mansions: 角, 亢, 氐, 房, 心, 尾, 箕; Southern mansions: 井, 鬼, 柳, 星, 张, 翼, 轸; Western mansions: 奎, 娄, 胃, 昴, 毕, 参, 觜; Northern mansions: 斗, 牛, 女, 虚, 危, 室, 壁

The moon moves through about one lunar mansion per day, so the 28 mansions were also used to count days. In the Tang Dynasty, Yuan Tiangang (袁天罡) matched the 28 mansions, seven luminaries and yearly animal signs, yielding combinations such as “horn-wood-flood dragon” (角木蛟).

Codes

Several coding systems are used for some special circumstances in order to avoid ambiguity, such as continuous day or year count.

- The heavenly stems is a decimal system.

- The earthly branches is a duodecimal system. The earthly branches are usually used to mark the dual hour (shí (時; 时) or shíchen (時辰; 时辰)) and climate terms.

- The stem-branches is a sexagesimal system. The heavenly stems and earthly branches match together and form 60 stem-branches. The stem-branches are used to mark the continuous day and year.

- The five elements of the Wu Xing are assigned to each of the stems, branches, and stem-branches. Yin and yang are assigned to all of these, with odd numbers as yang and even as yin.[citation needed]

| Stem-branches | Heavenly stems | Earthly branches | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu Xing | Stem, branch | Wu Xing | Stem | -gēng (1⁄10 of day) | Wu Xing | Branch | -shí (dual hour) | -yuè (month) | |||||||||||||

| metal | 1, 1 | 9, 9 | 7, 5 | 1, 7 | 9, 3 | 7, 11 | wood | 1 | jiǎ | 甲 | 19:12 | yīgēng | 1 | water | zǐ | 子 | 00:00 | Shíyīyuè (SYY) | 十一月 | ||

| 2, 2 | 10, 10 | 8, 6 | 2, 8 | 10, 4 | 8, 12 | 2 | yǐ | 乙 | 21:36 | èrgēng | 2 | soil | chǒu | 丑 | 02:00 | Làyuè (LAY) | 臘月 | ||||

| fire | 3, 3 | 1, 11 | 5, 1 | 3, 9 | 1, 5 | 5, 7 | fire | 3 | bǐng | 丙 | 0:00 | sāngēng | 3 | wood | yín | 寅 | 4:00 | Zhēngyuè (ZNY) | 正月 | ||

| 4, 4 | 2, 12 | 6, 2 | 4, 10 | 2, 6 | 6, 8 | 4 | dīng | 丁 | 2:24 | sìgēng | 4 | mǎo | 卯 | 6:00 | Èryuè (ERY) | 二月 | |||||

| wood | 5, 5 | 9, 7 | 7, 3 | 5, 11 | 9, 1 | 7, 9 | soil | 5 | wù | 戊 | 4:48 | wǔgēng | 5 | soil | chén | 辰 | 8:00 | Sānyuè (SNY) | 三月 | ||

| 6, 6 | 10, 8 | 8, 4 | 6, 12 | 10, 2 | 8, 10 | 6 | jǐ | 己 | 7:12 | morning | 6 | fire | sì | 巳 | 10:00 | Sìyuè (SIY) | 四月 | ||||

| water | 3, 1 | 1, 9 | 9, 5 | 3, 7 | 1, 3 | 9, 11 | metal | 7 | gēng | 庚 | 9:36 | midmorning | 7 | wǔ | 午 | 12:00 | Wǔyuè (WUY) | 五月 | |||

| 4, 2 | 2, 10 | 10, 6 | 4, 8 | 2, 4 | 10, 12 | 8 | xīn | 辛 | 12:00 | noon | 8 | soil | wèi | 未 | 14:00 | Liùyuè (LUY) | 六月 | ||||

| soil | 7, 7 | 5, 3 | 3, 11 | 7, 1 | 5, 9 | 3, 5 | water | 9 | rén | 壬 | 14:24 | late afternoon | 9 | metal | shēn | 申 | 16:00 | Qīyuè (QIY) | 七月 | ||

| 8, 8 | 6, 4 | 4, 12 | 8, 2 | 6, 10 | 4, 6 | 10 | guì | 癸 | 16:48 | evening | 10 | yǒu | 酉 | 18:00 | Bāyuè (BAY) | 八月 | |||||

| 11 | soil | xū | 戌 | 20:00 | Jiǔyuè (JUY) | 九月 | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | water | hài | 亥 | 22:00 | Shíyuè (SHY) | 十月 | |||||||||||||||

Time system

China has used the Western hour-minute-second system to divide the day since the Qing dynasty[1]. Before then, several systems of dividing the day were used depending on the era. Systems using multiples of twelve and ten were popular since they could be easily counted and aligned with the celestial stems and earthly branches.

In both old systems and the modern one, days begin and end at midnight although, colloquially, people refer to days beginning at dawn.

Week

As early as the Bronze Age Xia dynasty, days were grouped into nine- or ten-day weeks, called xún (旬).[2] Months were divided into 3 xún. The first 10 days was the early xún (上旬), the middle 10 days was the mid xún (中旬), and the last 9 or 10 days is the late xún (下旬). Japan adopted this pattern, though the 10-day-weeks were called jun (旬). In Korea, it was called sun (순,旬).

The structure of xún lead to work holidays being every five or ten days. During the Han dynasty, officials of the empire were legally required to rest every five days (沐; mù, from 休沐; xiūmù; 'wash rest')[citation needed], which allowed these breaks to happen twice a xún and 5–6 times a month. This was changed to every 10 days in the Tang dynasty[citation needed]. The name of these breaks was changed to huan (澣; 浣, again meaning "wash").

Grouping days into sets of ten is still used today in referring to specific natural events. Three Fu (三伏), a period of 29–30 days which are the hottest of the year, is a term reflecting that it lasts for three xún.[3] After the winter solstice, people traditionally count off 9 sets of 9 days (or 9 late xún) to figure out when winter ends.[4]

The seven-day week was adopted from the Hellenistic system by the 4th century CE, although by which route is not entirely clear. It was again transmitted to China in the 8th century by Manichaeans, via the country of Kang (a Central Asian polity near Samarkand).[5][b][c] It is the most predominantly used system in modern China.

Month

Months are defined by the time between new moons, which averages to 29 17⁄32 days. Instead of using half-days to balance the months with the lunar cycle, every other month of the year has 29 days (short month, 小月) and the rest have 30 (long month, 大月). Years start on a long month and alternate short-long-short-long until the year ends.

A 12-month-year using this system has only 354 days. Using only 12 months per year would cause significant drift from the tropical year. To fix this, traditional Chinese years alternate a 13-month-year every other year. The 13-month version has the same alternation of long and short months, but adds a 30-day month at the end of the year. Years with 12 months are called common years, and years with 13 months are called long years.

Though most of the above rules applied until the Tang Dynasty, different eras used different systems to keep the lunar and solar years aligned. For example, the synodic month of the Taichu calendar was 29 43⁄81 days. The 7th century Wùyín Yuán Calendar of the Tang dynasty was the first to determine month length by the real synodic month, instead of using the cycling method. Since then, month lengths have been determined by observation and prediction, with few exceptions.[d]

The days of the month are numbered beginning with 1, and the day's number is always written with two characters.

- Days 1 to 10 are written with the Chinese numeral of the day number, preceded by the character Chū (初). For example, Chūyī (初一) is the 1st day of the month, and Chūshí (初十) is the 10th.

- Days 11 to 20 are written as regular Chinese numerals. For example, Shíwǔ (十五) is the 15th day of the month, and Èrshí (二十) is the 20th.

- Days 21 to 29 are written with the character Niàn (廿) before the characters for 1 through 9. For example, Niànsān (廿三) is the 23rd day of the month.

- Day 30, for months that have it, is written as the regular Chinese numeral Sānshí (三十).

As a convention, history books use days of the month as numbered with the 60 stem-branches. For example:

天聖元年....二月....丁巳, 奉安太祖、太宗御容于南京鴻慶宮.

Tiānshèng 1st year....Èryuè....Dīngsì, the emperor's funeral was at his temple, and the imperial portrait was installed in Nanjing's Hongqing Palace.

Because astronomical observation is used to determine month lengths, dates on this calendar correspond to moon phases. The first day of each month is the new moon. In the 7th or 8th day of each month, the first quarter moon is visible in the afternoon and early evening. In the 15th or 16th day of each month, the full moon is visible all night. In the 22nd or 23rd day of each month, the last quarter moon is visible late at night and in the morning.

Since the beginning of the month is determined by the time when the new moon occurs, other countries using this calendar use their own time standards to calculate it. This results in deviations. For instance, the first new moon in 1968 was at UTC Jan 29 16:29. Since North Vietnam used the UTC+7 timezone to calculate their Vietnamese calendar, and South Vietnam used the longitude of Beijing to calculate theirs, North Vietnam started the holiday of Tết at Jan 29 23:29, while South Vietnam started it at Jan 30 00:15. Using this time difference allowed asynchronous attacks in Tet Offensive.[6]

Solar year and solar term

The solar year (歲; 岁; Suì) is the time between winter solstices. The solar year is divided further into 24 solar terms. In ancient China, solar terms were estimated as 1⁄24 of the solar year, or about 15 7⁄32 days.[citation needed] Starting from the 17th century, when the Shixian Calendar of Qing dynasty was adopted, the solar year was determined by the real tropical year instead.[citation needed] The solar terms correspond to intervals of 15° along the ecliptic.

Different version of traditional Chinese calendar might have different average solar year length. One solar year of the Tàichū calendar from 1st century BC is 365 385⁄1539—or 365.25016—days. A solar year of the 13th century Shòushí calendar is 365 97⁄400—or 365.24250—days, the same as the Gregorian calendar. The additional 0.00766-day from the Tàichū calendar leads to a one-day shift every 130.5 years.

Couples of solar terms are climate terms, or solar months. The first of each couple is "pre-climate" (節氣; 节气; Jiéqì), and the second of the each couple is "mid-climate" (中氣; 中气; Zhōngqì). In the list below, the odd numbers are the pre-climates, and the even numbers are the mid-climates.

The solar term system is not suitable for the place between regression line, such as Hongkong, for there must be two summer solstices in a year.

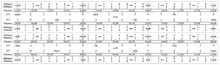

| Year mod 19 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| usually after month 7 or 8 | usually after month 6 or 5 | usually after month 4 | usually after month 10 | usually after month 3 or 2 | usually after month 7 or 6 | usually after month 5 | usually after month 4 or 3 | |

| 1862 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 1881 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 1900 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | |

| 1919 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 1938 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 3 | |

| 1957 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | |

| 1976 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 1995 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | |

| 2014 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

| 2033 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 3 | |

| 2052 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | |

| 2071 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | |

| 2090 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | |

- FTC 小寒 First Term of Cold Season

- STC 大寒 Second Term of Cold Season

- VC 立春 Vernal commence (start of spring)

- LTC 雨水 Last Term of Cold Season

- FTR 惊蛰 First Term of Rainy Season

- VE 春分 Vernal Equinox

- STR 清明 Second Term of Rainy Season

- LTR 谷雨 Last Term of Rainy Season

- SC 立夏 Summer commence

- FTG 小满 First Term of Growing Season

- STG 芒种 Second Term of Growing Season

- SS 夏至 Summer Solstice

- FTH 小暑 First Term of Hot Season

- STH 大暑 Second Term of Hot Season

- AC 立秋 Autumn Commence

- LTH 处暑 Last Term of Hot Season

- FTD 白露 First Term of Dew Season

- AE 秋分 Autumn Equinox

- STD 寒露 Second Term of Dew Season

- LTD 霜降 Last Term of Dew Season

- WC 立冬 Winter Commence

- FTS 小雪 First Term of Snowy Season

- STS 大雪 Second Term of Snowy Season

- WS 冬至 Winter Solstice

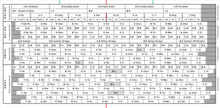

| Month | Days after WS | Start time 1 |

Term 1 name |

in days after WS | Start time 2 |

Term 2 name |

in days after WS | End time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ws | WS | 0 | 18:44 | |||||

| 0 | 8 | 14:53 | FTC | 15 | 11:55 | STC | 30 | 5:23 |

| 1 | 38 | 8:06 | VC | 44 | 23:34 | LTC | 59 | 19:31 |

| 2 | 67 | 22:58 | FTR | 74 | 17:32 | VE | 89 | 18:28 |

| 3 | 97 | 10:57 | STR | 104 | 22:17 | LTR | 120 | 5:26 |

| 4 | 126 | 20:16 | SC | 135 | 15:30 | FTG | 151 | 4:30 |

| 5 | 156 | 3:44 | STG | 166 | 19:36 | SS | 182 | 12:24 |

| 6 | 185 | 10:30 | FTH | 198 | 5:50 | STH | 213 | 23:15 |

| i | 214 | 17:45 | AC | 229 | 15:39 | |||

| 7 | 244 | 2:30 | LTH | 245 | 6:20 | FTD | 260 | 18:38 |

| 8 | 273 | 13:29 | AE | 276 | 4:01 | STD | 291 | 10:22 |

| 9 | 303 | 3:11 | LTD | 306 | 13:26 | WC | 321 | 13:37 |

| 10 | 332 | 19:42 | FTS | 336 | 11:04 | STS | 351 | 6:32 |

| ws | 362 | 14:30 | WS | 366 | 0:27 | |||

In general, there are 11 or 12 complete months—plus 2 incomplete months which border the winter solstice—in a solar year. The 11 mid-climates except the winter solstice are in the 11 or 12 complete months. The complete months are numbered from 0 to 10, and the incomplete months together are considered to be the 11th month.

The first month without a mid-climate is the leap month or intercalary month. Leap months are numbered using the character for "intercalary", rùn 閏, then the name of the month they follow. In 2017, the intercalary month after month 6 was called Rùn Liùyuè, or "intercalary sixth month" (閏六月). When writing or using shorthand, it was referred to as 6i or 6+. The next intercalary month occurs in 2020 after month 4, so it will be called Rùn Sìyuè (閏四月) and 4i or 4+ will be used as shorthand.

Lunisolar year

The lunisolar year starts from the first spring month, called Zhēngyuè (正月; 'capital month') and ends at the last winter month, called Làyuè (臘月; 腊月; 'sacrificial month'). All other months are named for the month number. If a leap month falls after month 11—as it will in 2033—the 11th month will be Shíèryuè (十二月; 'twelfth month') and the leap month will be Làyuè.

Years were numbered after the reign title in Ancient China, but the reign title was no longer used after the founding of PRC in 1949. People use the stem-branches to demarcate the years. For example, the year from February 8, 2016 to January 27, 2017 was a Bǐngshēn year (丙申年), Template:Chinese Year long.

To Encode the date in the Chinese calendar, the flag of the intercalary month should be considered. For example, Run Liuyue 6, Dingyounian: 408-6i-06 (Timestamp: 40806106)

In Tang Dynasty, the earthly branches are used to mark the months for about 150 days (Dec, 761~May, 762).[e] At that time, the year starts from the month with Winter Solstice, and the month from Zhengyue to Layue are named as: Yinyue, Maoyue, Chenyue, Siyue, Wuyue, Weiyue, Shenyue Youyue, Xuyue, Haiyue, Ziyue, and Chouyue.

Estimate the Chinese date

- A month in the Chinese calendar is 29 or 30 days long, and a month in the Gregorian calendar is 30 or 31 days long (except for February). So, we may estimate the Chinese date if we know the bias between Layue 1st and January 1. In general, from Eryue/March, the Chinese date moves 1 day backward, after a month; the Chinese date moves a day forward after Zhengyue/February. If the bias is over 29 days, consider if there's an intercalary month before.

- The date of the solar term in the Gregorian calendar is more or less fixed. In general, the date of the solar term in the Chinese calendar can vary ±15 days around the fixed date. The first climate term is around the 1st of the corresponding month, and the middle climate term is around the 15th of the corresponding month.

- A solar year is about 365 1⁄4 days, and 12 lunar months are about 354 3⁄8 days. So the Chinese date moves about 11 days backward or 19 days forward.

- If the Chinese New Year is in January, there's an intercalary month in that year.

- The Chinese date is more or less fixed after 19 years (or 11 years occasionally) later. But dates near intercalary months always are tricky. The dates in the winter of the nominal year of Merton cycle are strange too, such as 2014+19n. There are 7 leap years in 19 years, but not always. The date of the Chinese New Year and the leap month not only move forward every eight years but also move slowly along with the 19-year cycle. For details see the table below.

| Nineteen-year cycle for Chinese calendar | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cell: year mod 19 | Column: plus 8 mod 19 | Row: plus 11 mod 19 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 |

| 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 |

| 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 |

| 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 08 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 |

| 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 |

| 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 |

| 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 |

| 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 |

| 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 |

| 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 |

| 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 |

| 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 |

| 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 |

| 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 |

| 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 | 14 |

| 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 | 06 |

| 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 | 17 |

| 17 | 06 | 14 | 03 | 11 | 00 | 08 | 16 | 05 | 13 | 02 | 10 | 18 | 07 | 15 | 04 | 12 | 01 | 09 |

| Leap years | Common years | |||||||||||||||||

| M02 M03 J21 J23 F19 F20 |

M02 M04 J22 J24 -- -- |

M03 M05 J24 J26 -- -- |

M04 M06 J25 J28 -- -- |

M05 M06 J26 J29 -- -- |

M06 M07 J28 J30 -- -- |

M06 M11 J30 F01 -- -- |

M08 M10 J31 F02 -- -- |

-- -- F02 F04 -- -- |

-- -- F03 F06 -- -- |

-- -- F05 F07 -- -- |

-- -- F07 F08 -- -- |

-- -- F08 F10 -- -- |

-- -- F10 F12 -- -- |

-- -- F11 F14 -- -- |

-- -- F13 F15 -- -- |

-- -- F14 F16 -- -- |

-- -- F16 F18 -- -- |

-- -- F18 F20 -- -- |

| Earliest | Leap months and dates of New Year's Day (M: Month | J: January | F: February) | Latest | ||||||||||||||||

Graphical representation

A typical graphical representation of the Chinese calendar is the spring cattle diagram (春牛圖; 春牛图), which help people calculate the date. In this diagram:

- The color of the cattle's head marks the Wu Xing element of the year's stem.

- If the cattle's mouth is closed, it is a yin year; if open, it is a yang year.

- The color of the cattle body marks the branch of the year.

- The color of the cattle tail marks the Wu Xing element of the stem for the first day of spring (立春).

- If the cattle tail is on the left, the first day of spring is a yang day; if on the right, it's a yin day.

- The color of the cattle's legs marks the branch of the first day of spring.

- If the cowherd stands ahead the cattle, the first day of spring is more than 5 days after the new year; if the cowherd stands behind the cattle, the first day of spring is more than 5 days before the new year; otherwise the difference between the new year and the first day of spring is within 5 days.

Age recognition in China

In China, age for official use is based on the Gregorian calendar. For traditional use, age is based on the Chinese calendar. For the first year from the birthday, the child is considered one year old. After each New Year's Eve, add one year. "Ring out the old age and ring in the new one (辭舊迎新; 辞旧迎新; cíjiù yíngxīn)" is the literary express of New Year Ceremony. For example, if one's birthday is Làyuè 29th 2013, he is 2 years old at Zhēngyuè 1st 2014. On the other hand, people say months old instead of years old, if someone is too young. It is that the age sequence is "1 month old, 2 months old, ... 10 months old, 2 years old, 3 years old...".

After the actual age (實歲; 实岁) was introduced into China, the Chinese traditional age was referred to as the nominal age (虛歲; 虚岁). Divided the year into two halves by the birthday in the Chinese calendar,[f] the nominal age is 2 older than the actual age in the first half, and the nominal age is 1 older than the actual age in the second half (前半年前虛兩歲,後半年虛一歲; 前半年前虚两岁,后半年虚一岁).[g]

Birthday issue

Just as it is awkward to define the birthday of someone born on the 29th of February in the Gregorian calendar, special rules are used for birthdays or other anniversaries during the intercalary month or on the 30th day.

- If someone was born in an intercalary month (except intercalary Shi'eryue), his birthday is in the common month (the month before the intercalary month).

- If someone was born in Shi'eryue, and Layue is the intercalary Shi'eryue, his birthday is in Layue (the last month of a year).

- If someone was born at 30th day of a month, his birthday is the last day of the month, i.e. the 30th day if that exists, or the 29th day if it does not.

Year number system

- Era system

In the Ancient China, years were numbered from 1, beginning from the next year after a new emperor ascended the throne or the current emperor announced a new era name. The first reign title was Jiànyuán (建元; 'era establishment', from 140 BCE), and the last reign title was Xuāntǒng (宣統; 宣统, from 1908 CE). The era system was abolished in 1912 CE, after which the Current Era or Republican era was used. The epoch of the Current Era is just the same as the era name of Emperor Ping of Han, Yuánshí (元始; 'era beginning').

- Stem-branches system

The 60 stem-branches were used to mark the date continually from Shang Dynasty. Before Han Dynasty, people knew the orbital period of Jupiter is about 4332 days, which is about 12*361 days. So, the orbital period of Jupiter was divided into 12 periods, which was used to number the year. The Jupiter was called as the star of age (嵗星; 岁星; suìxīng), and the 1/12 Jupiter orbital period was called as the age (嵗; 岁; suì).

361 days is just 6 cycles of 60-stem-branches, so the stem-branches of the first day move forward one after each sui. The first day of each sui was called as the sui capital (太嵗; 太岁; tàisuì).

And the stem-branches of the taisui was used to mark the year. Obviously, there're two taisui in some year for the sui is shorter than solar rear. About after each 86 year, a taisui was leaped. The leaped of the sui was called as beyond the star (超辰; chāochén).

At the eastern Han Dynasty, the chaochen are abolished, and the 60 stem-branches are used to mark year continually without leap.

The Stem-branches year number system provided a solution for the defect of era system (unequal length of the reign titles)

- Continuous year numbering

Occasionally, nomenclature similar to that of the Christian era has been used, such as[7]

- Anno Huángdì (黄帝紀年), referring to the beginning of the reign of the Yellow Emperor, 2698+AD=AH

- Anno Yáo (唐尧紀年), referring to the beginning of the reign of Emperor Yao, 2156+AD=AY

- Anno Gònghé (共和紀年), referring to the beginning of the Gonghe Regency, 841+AD=AG

- Anno Confucius (孔子紀年), referring to the birth year of Confucius, 551+AD=AC

- Anno Unity (統一紀年), referring to the beginning of the reign of Qin Shi Huang, 221+AD=AU

No reference date is universally accepted. The most popular is the Christian Era, such as in "Today is gongli (GC) 1984 nian (year)... nongli (CC)...".

On January 2, 1912, Sun Yat-sen declared a change to the official calendar and era. In his declaration, January 1, 1912 is called Shíyīyuè 13th, 4609 AH which assumes an epoch (1st year) of 2698 BCE. This declaration was adopted by many overseas Chinese communities outside Southeast Asia such as San Francisco's Chinatown.[8]

In the 17th century, the Jesuits tried to determine what year should be considered the epoch of the Han calendar. In his Sinicae historiae decas prima (first published in Munich in 1658), Martino Martini (1614–1661) dated the ascension of the Yellow Emperor to 2697 BC, but started the Chinese calendar with the reign of Fuxi, which he claimed started in 2952 BCE. Philippe Couplet's (1623–1693) Chronological table of Chinese monarchs (Tabula chronologica monarchiae sinicae; 1686) also gave the same date for the Yellow Emperor. The Jesuits' dates provoked great interest in Europe, where they were used for comparisons with Biblical chronology.

Modern Chinese chronology has generally accepted Martini's dates, except that it usually places the reign of the Yellow Emperor in 2698 BC and omits the Yellow Emperor's predecessors Fuxi and Shennong, who are considered "too legendary to include".

Starting in 1903, radical publications started using the projected date of birth of the Yellow Emperor as the first year of the Han calendar. Different newspapers and magazines proposed different dates. Jiangsu, for example, counted 1905 as year 4396 (use an epoch of 2491 BCE), whereas the newspaper Ming Pao (明報; 明报) reckoned 1905 as 4603 (use an epoch of 2698 BCE). Liu Shipei (劉師培; 1884–1919) created the Yellow Emperor Calendar, now often used to calculate the date, to show the unbroken continuity of the Han race and Han culture from earliest times. Liu's calendar started with the birth of the Yellow Emperor, which he determined to be 2711 BC. There is no evidence that this calendar was used before the 20th century.[9] Liu calculated that the 1900 international expedition sent by the Eight-Nation Alliance to suppress the Boxer Rebellion entered Beijing in the 4611th year of the Yellow Emperor.

- Calendric epoch

There is an epoch for each version of the Chinese calendar, which is called Lìyuán (曆元; 历元). The epoch is the optimal origin of the calendar, and it is a Jiǎzǐrì, the first day of a lunar month, and the dark moon and solstice are just at the midnight (日得甲子夜半朔旦冬至). And tracing back to a perfect day, such as that day with the magical star sign, there's a supreme epoch (Chinese: 上元; pinyin: shàngyuán). The continuous year based on the supreme epoch is shàngyuán jīnián (上元積年; 上元积年). More and more factors were added into the supreme epoch, and the shàngyuán jīnián became a huge number. So, the supreme epoch and shàngyuán jīnián were neglected from the Shòushí calendar.

- Yuán-Huì-Yùn-Shì system

Shao Yong (邵雍 1011–1077), a philosopher, cosmologist, poet, and historian who greatly influenced the development of Neo-Confucianism in China, introduced a time system in his The Ultimate which Manages the World (皇極經世; 皇极经世; Huángjíjīngshì)

In his time system, 1 yuán (元), which contains 12'9600 years, is a lifecycle of the world. Each yuán is divided into 12 huì (會; 会). Each huì is divided into 30 yùn (運; 运), and each yùn is divided into 12 shì (世). So, each shì is equivalent to 30 years. The yuán-huì-yùn-shì corresponds with nián-yuè-rì-shí. So the yuán-huì-yùn-shì is called the major tend or the numbers of the heaven, and the nián-yuè-rì-shí is called the minor tend or the numbers of the earth.

The minor tend of the birth is adapted by people for predicting destiny or fate. The numbers of nián-yuè-rì-shí are encoded with stem-branches and show a form of Bāzì. The nián-yuè-rì-shí are called the Four Pillars of Destiny. For example, the Bāzì of the Qianlong Emperor is Xīnmǎo, Dīngyǒu, Gēngwǔ, Bǐngzǐ (辛卯、丁酉、庚午、丙子). Shào's Huángjíjīngshì recorded the history of the timing system from the first year of the 180th yùn or 2149th shì (HYSN 0630-0101, 2577 BC) and marked the year with the reign title from the Jiǎchénnián of the 2156th shì (HYSN 0630-0811, 2357 BC, Tángyáo 1, 唐堯元年; 唐尧元年). According to this timing system, 2014-1-31 is HYSN/YR 0712-1001/0101.

The table below shows the kinds of year number system along with correspondences to the Western (Gregorian) calendar. Alternatively, see this larger table of the full 60-year cycle.

| Year in cycle | s,b | Gānzhī (干支) | Year of the... | CE[1] | AR[1] | HYSN[2] | AH[3] | Begins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 7,3 | gēngyín (庚寅) | Metal Tiger | 2010 | 99 | 0712-0927 | 4707 | February 14 |

| 28 | 8,4 | xīnmǎo (辛卯) | Metal Rabbit | 2011 | 100 | 0712-0928 | 4708 | February 3 |

| 29 | 9,5 | rénchén (壬辰) | Water Dragon | 2012 | 101 | 0712-0929 | 4709 | January 23 |

| 30 | 10,6 | guǐsì (癸巳) | Water Snake | 2013 | 102 | 0712-0930 | 4710 | February 10 |

| 31 | 1,7 | jiǎwǔ (甲午) | Wood Horse | 2014 | 103 | 0712-1001 | 4711 | January 31 |

| 32 | 2,8 | yǐwèi (乙未) | Wood Goat | 2015 | 104 | 0712-1002 | 4712 | February 19 |

| 33 | 3,9 | bǐngshēn (丙申) | Fire Monkey | 2016 | 105 | 0712-1003 | 4713 | February 8 |

| 34 | 4,10 | dīngyǒu (丁酉) | Fire Rooster | 2017 | 106 | 0712-1004 | 4714 | January 28 |

| 35 | 5,11 | wùxū (戊戌) | Earth Dog | 2018 | 107 | 0712-1005 | 4715 | February 16 |

| 36 | 6,12 | jǐhài (己亥) | Earth Pig | 2019 | 108 | 0712-1006 | 4716 | February 5 |

1 As of the beginning of the Chinese year. AR=Anno the Republic of China

2 Timestamp according to Huángjíjīngshì, as a format of Huìyùn-Shìnián.

3 Huángdì era, using an epoch (year 1) of 2697 BC. Subtract 60 if using an epoch of 2637 BC. Add 1 if using an epoch of 2698 BC.

Phenology

- The plum rains season is the rainy season during the late spring and early summer. The plum rains season starts on the first Bǐngrì after the Corn on Ear, and ends on the first Wèirì after the Moderate Heat.

- The Sanfu days are the three sections from the first Gēng-day after the summer solstice. The first section is 10 days long, and named the fore fu (初伏; chūfú). The second section is 10 or 20 days long, and named the mid fu (中伏; zhōngfú). The last section is 10 days long from the first Gēng-day after autumn commences, and named the last fu (末伏; mòfú).

- The Shujiu cold days are the nine sections from the winter solstice. Each section is 9 days long. The shǔjǐu are the coldest days, and named with an ordinal number, such as Sìjǐu (四九).

Festivals

In the Sinosphere, the traditional festivals are calculated using the date or solar terms, and are considered auspicious.

| Festival | English | Define | Original Define (Han Dynasty) | Date of the following... | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major traditional festivals on fixed date | |||||

| 臘日/腊日 Lari |

0008 Sacrifice Day |

Làyuè 8 | The third Xuri (戌) after the Winter Solstice | 2017-01-05 | |

| 小年 Xiaonian |

0023/0024 Preliminary Eve |

Làyuè 23/24 | 23-officers, 24-civilians, 25-monks, for convenience |

2017-01-20 2017-01-21 |

the cleanup day before New Year's Week |

| 除夕 Chuxi |

0100 New Year's Eve |

the last day of the year, Làyuè 29 or 30 | 2017-01-27 | a statutory holiday | |

| 春節/春节 Chunjie |

0101 New Year's Day |

The first day of the year, Zhēngyuè 1 | 2017-01-28 | a statutory holiday | |

| 上元 Shangyuan |

0115 Shangyuan |

Zhēngyuè 15 | The first full moon of the year | 2017-02-11 | Also called as Yuanxiao (the night of the first full moon), an annual carnival in ancient China |

| 上巳 Shangsi |

0303 Outing Festival |

Sānyuè 3 | The first Siri (巳) of Sanyue | 2017-03-30 | a version of Qingmin Festival, The origin of Thailand water splashing festival |

| 佛誕/佛诞 Fodan |

0408 Buddha's Birthday |

Sìyuè 8 | 2017-05-03 | a statutory holiday in Hong Kong SAR | |

| 端午 Duanwu |

0505 Dragon Boat Festival |

Wǔyuè 5 | The First Wuri (午) of Wuyue | 2017-05-30 | a statutory holiday |

| 七夕 Qixi |

0707 Star Festival |

Qīyuè 7 | 2017-08-28 | Ingenuity Maiden's Day | |

| 中元 Zhongyuan |

0715 Ghost Festival |

Qīyuè 15 | The full moon at the mid-year | 2017-09-05 | the worship of ancestors |

| 中秋 Zhongqiu |

0815 Mid-Autumn Festival |

Bāyuè 15 | The full moon at the mid-autumn | 2017-10-04 | Reunion Day, a statutory holiday |

| 重陽/重阳 Chongyang |

0909 Climbing Festival |

Jiǔyuè 9 | 2017-10-28 | Regarded as Elder's Day in China

a statutory holiday in Hong Kong SAR | |

| 十月朝 Shiyue Chao |

1001 Shiyue Worship |

Shíyuè 1 | The New Year's Day of Qin Calendar | 2017-11-18 | Issue Royal calendar (almanac) for the following year. |

| 下元 Xiayuan |

1015 Spirit Festival |

Shíyuè 15 | The first full moon in Qin calendar | 2017-12-02 | the worship of worthy |

| Major traditional festivals on solar term | |||||

| 立春 Lichun |

Beginning of Spring | The day that Spring commences about February 4 |

Zhēngyuè 8 (February 3) |

The day of the Stimulation of Agriculture | |

| 寒食 Hanshi |

Cold Food Festival | the 105th day after the Winter Solstice about April 4 |

Sānyuè 7, 2017 (April 3) |

The fast before the worship of ancestors at Qingming Festival. | |

| 清明 Qingming |

Qingming Festival | The day of the solar term of Bright and Clear about April 5 |

Sānyuè 8, 2017 (April 4) |

The day of the worship of ancestors, a statutory holiday | |

| 冬至 Dongzhi |

Winter Solstice | The day of the Winter Solstice about December 21 |

Shíyīyuè 5, 2017 (December 22) |

The node of the solar years | |

| 春社/秋社 Chunshe/Qiushe |

Spring/Autumn Pray | the fifth Wùrì (戊) after Spring/Autumn Commences | March 21 September 23 |

a version of Spring/Autumn equinox | |

| The traditional business festivals | |||||

| 開市/开市 Kaishi |

0105 Opening Day |

Zhēngyuè 5 | In the old days, merchants used to open their stores from Zhēngyuè 5, and host a prayer service on that day. God of Wealth's Day, which the prayer service is called God of Wealth is Welcome. | ||

| 頭牙/尾牙 头牙/尾牙 Touya & Weiya |

0202/0016 First/Last Thanksgiving |

Èryuè 2 / Làyuè 16 | In the Ancient China, business owners hosted the Yaji rites (Chinese: 牙祭; pinyin: Yaji) at the 2nd and 16th day of each month from Eryue to Layue, to reward the local guardian god and their employees. The First/Last Thanksgiving rite is held on Èryue 2/Làyuè 16. | ||

History

Earlier Chinese calendars

Before the Zhou dynasty, the Chinese calendars used a solar calendar.

According to Ancient Chinese literature, the first version was the five-phases calendar (五行曆; 五行历), which came from the tying knots culture. In the five-phases calendar, a year was divided into five phases which were expressed by five ropes. Each rope was folded into halves, and the day in the corner was the capital day (行御). They're three sections in each halves, and the Chinese Character of phase is the pictograph of the rope of the tying knots. The ten half-ropes were arranged into a row, and a man shape was engraved by the ropes. The part of man shape derived into 10 heaven stems. The days in each sections were recorded with 12 earthly branches. So, in the five-phases calendar, a year is fives phases or ten months, and a phase is six sections or 73 days. The remainder of each phases are marked in the Hetu, which is found in Song Dynasty.

The second version is the four-seasons calendar (四時八節曆; 四时八节历). In the four-seasons calendar, the days were counting by ten, and three ten-days weeks were built into a month. There were 12 months in a year, and a week were intercalated in the hot month. In the age of four-seasons calendar, the 10 heaven stems and 12 earthly branches were used to mark days synchronously.

The third version is the balanced calendar (調曆; 调历) a year was defined into 365.25 days, and the month was defined into 29.5 days. And after each 16 months, a half-month was intercalated. There half-months were merged into months later, and the archetype of the Chinese calendar was brought out in the Spring and Autumn ages.

Oracle bone records indicate that the calendar of Shang Dynasty were a balanced calendar, and the 12, 13, even 14 months were packed into a year roughly. Generally, the month after the winter solstice was named as the capital month (正月).[10]

Ancient Chinese calendars

Pre-Qin dynasty calendars

In Zhou dynasty, the authority issued the official calendar, which is a primitive lunisolar calendar. The year beginning of Zhou's calendar (周曆; 周历) is the day with dark moon before the winter solstice, and the epoch is the Winter Solstice of a Dīngyǒu year.

Some remote vassal states issued their own calendars upon the rule of Zhou's calendar, such as:

- The epoch of the Lu's calendar (魯曆; 鲁历) is the winter solstice of a Gēngzǐ year.

During the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, Some vassal states got out of control of Zhou, and issues their own official calendar, such as:

- Jin issued the Xia's calendar (夏曆; 夏历), with a year beginning of the day with the nearest darkmoon to the Vernal Commences. The epoch of Xia's calendar is the Vernal Commences of a Bǐngyíng year.

- Qin issued the Zhuanxu's calendar (顓頊曆; 颛顼历), with a year beginning of the day with the nearest darkmoon to the Winter Commences. The epoch of Zhuanxu's calendar is the Winter Commences of a Yǐmǎo year.

- Song resumed the Yin's calendar (殷曆; 殷历), with a year beginning of the day with the darkmoon after the Winter Solstice. The epoch of Yin's calendar is the Winter Solstice of a Jiǎyíng year.

These six calendars are called as the six ancient calendars (古六曆; 古六历), and are the quarter remainder calendars (四分曆; 四分历; sìfēnlì). The months of these calendars begin on the day with the darkmoon, and there are 12 or 13 month within a year. The intercalary month is placed at the end of the year, and called as 13th month.

The modern version of the Zhuanxu's calendar is the Chinese Qiang calendar and Chinese Dai calendar, which are the calendar of mountain peoples.

Calendar of the Qin and early Han dynasties

After Qin Shi Huang unified China under the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE, Qin's calendar (秦曆; 秦历) was promulgated. The Qin's calendar follows the rules of Zhuanxu's calendar, but the month order follows the Xia calendar. The months in the year are from the 10th month to the 9th month, and the intercalary month is called as the second Jiuyue (後九月; 后九月). In the early Han dynasty, the Qin calendar continued to be used.

Taichu calendar and the calendars from the Han to Ming dynasties.

Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty introduced reforms halfway through his administration. His Taichu or Grand Inception Calendar (太初曆; 太初历) introduced 24 solar terms which determined the month names. The solar year was defined as 365 385/1539 days, and divided into 24 solar terms. Each couples of solar terms are associated into 12 climate terms. The lunar month was defined as 29 43/81 days and named according to the closest climate term. The mid-climate in the month decides the month name, and a month without mid-climate is an intercalary month.

The Taichu calendar established the frame of the Chinese calendar, Ever since then, there have been over 100 official calendars in Chinese which are consecutive and follow the structure of Tàichū calendar both. There're several innovation in calendar calculation in the history of over 2100 years, such as:

- In the Dàmíng Calendar released in Tiānjiān 9 (天监九年, 510) of the Liang dynasty, Zhu Chongzhi introduced the equation of equinoxes.

- Actual syzygy method was adopted to decide the month from the Wùyín Yuán Calendar, which was released in Wǔdé 2 (武德二年, 619) of the Tang dynasty.

- The real measured data was used in calendar calculation from Shòushí Calendar, which was released in Zhìyuán 18 (至元十八年, 1281) of the Yuan dynasty. And the tropical year is fixed at 365.2425 days, the same as the Gregorian calendar established in 1582,[11] and derived spherical trigonometry.[12][13][14]

Modern Chinese calendars

The Chinese calendar lost the status of the official statutory calendar in China at the beginning of the 20th century,[15] but its use has continued for various purposes.

In 1928 the Republic of China adopted the UTC+8 timezone, instead of Beijing Mean Solar Time, and so Chinese calendars produced in mainland China switched to using UTC+8 in the following year. However, the switch in time standard used in Chinese calendars has not been universally adopted in areas such as Taiwan and Hong Kong, and some calendars still followed the last calendar of the Qing dynasty that was published in 1908. In 1978, this practice caused confusion regarding the date of the Mid-autumn festival, and as a result those areas switched to the UTC+8-based Chinese calendar thereafter.[16]

Shíxiàn calendar

In the late Ming dynasty, Xu Guangqi and his colleagues worked out the new calendar based on Western astronomical arithmetic. But the new calendar was not released before the end of the Ming dynasty. In the early Qing dynasty, Johann Adam Schall von Bell submitted the calendar to the Shunzhi Emperor. The Qing government released the calendar under the name the Shíxiàn calendar, which means seasonal charter. In the Shíxiàn calendar, the solar terms each correspond to 15° along the ecliptic. It meant the Chinese calendar can be used as astronomical calendar. However, the length of the climate term near the perihelion is shorter than 30 days and there may be two mid-climate terms. The rule of the mid-climate terms decides the months, which is used for thousands years, lose its validity. The Shíxiàn calendar changed the rule to "decides the month in sequence, except the intercalary month."

Current Chinese calendar

The version of the traditional Chinese calendar currently being used follows the rules of the Shíxiàn calendar, except that:

- The baseline is Chinese Standard Time rather than Beijing local time.

- Actual astronomical data is used rather than only theoretical mathematical calculations.

Proposals to optimize the Chinese calendar

To optimize the Chinese calendar, astronomers have released many proposed changes. A typical proposal was released by Gao Pingzi (高平子; 1888-1970), a Chinese astronomer who was one of the founders of Purple Mountain Observatory. In his proposal, the month numbers are calculated before the dark moons and the solar terms were rounded to the day. Under his proposal, the month numbers are the same for the Chinese calendar upon different time zones.

As the intercalary month is determined by the first month without mid-climate and the exact time when each mid-climate happen would vary according to time zone, countries that have adopted the calendar but calculate with their own time could vary from the one used in China because of this. For instance, the 2012 FTG happened in UTC May 20 15:15, which would translate to May 20 23:15 in UTC+8, making FTG the mid-climate for the fourth month of that traditional Chinese year [April 21 ~ May 20 in Gregorian calendar], but in Korea it happened in May 21 00:15 in UTC+9, and as new moon take place in May 21 in that month, therefore the month before that would only consist of the SC solar term, lacking mid-climate. As a result, the month starting at April 21 would be an intercalary month in Korean calendar, but not in Chinese Calendar, and the intercalary month in Chinese calendar would start in the month after, in the fifth month starting from May 21, which would only consist of the solar term STG, while the month in Korean Calendar would have both FTG and STG solar term in it.

Other practices

Among the ethnic groups inhabiting the mountains and plateaus of southwestern China, and those living in the grasslands of northern China, their civil calendars show a diversity of practice based upon their characteristic phenology and culture, but they are based on the algorithm of the Chinese calendar of different periods, especially those of the Tang dynasty and pre-Qin dynasty period.

See also

- Culture of China

- Dates in Chinese

- East Asian age reckoning

- Festivals of Korea

- Guo Shoujing, an astronomer tasked with calendar reform during the 13th century

- List of festivals in Vietnam

- Public holidays in China

- Sexagenary cycle

- Traditional Chinese timekeeping

- Chinese Traditional Date and Time

Notes

- ^ Despite the literal meaning of the word 農曆 as "farming calendar", this is a cultural/religious calendar, and only loosely based on agricultural traditions. It was first designated 農曆 by the newspapers of the mainland of China on 1 January 1968[citation needed], as part of the Socialist Education Movement. The traditional calendar was labelled with "農", meaning "farming", and was regarded as part of the Four Olds to be eliminated. A more accurate translation of "農曆" is "rural calendar", since usage of the traditional Chinese calendar today is confined to rural areas (except when calculating the Chinese New Year). This is particularly ironic since the Gregorian calendar is more convenient for farming than the traditional Chinese calendar.[citation needed]

- ^ The 4th-century date, according to the Cihai encyclopedia,[year needed] is due to a reference to Fan Ning (範寧; 范宁), an astrologer of the Jin dynasty.

- ^ The renewed adoption from Manichaeans in the 8th century (Tang dynasty) is documented with the writings of the Chinese Buddhist monk Yi Jing and the Ceylonese Buddhist monk Bu Kong.

- ^ For instance, the 19th year in Wùyín Yuán Calendar was expected to have 4 consecutive long months if the real synodic method was used. Since this broke the traditional pattern of alternating long and short months, they reverted to using the cycling method to determine month length for that year.[citation needed]

- ^ 新唐書•本紀六 肅宗、代宗

(上元)二年……,九月壬寅,大赦,去“乾元大圣光天文武孝感”号,去“上元”号,称元年,以十一月为岁首,月以斗所建辰为名。…。

元年建子月癸巳[2],…。己亥[9],…。丙午[16],…。己酉[29],…。庚戌[30],…。[初一壬午大雪,十七冬至]

建丑月辛亥[1],…。己未[9],…。乙亥[25],…。[初一辛亥,初三小寒,十八大寒]

宝应元年建寅月甲申[4],…。乙酉[5],…。丙戌[3],…。甲辰[24],…。戊申[28],…。[初一辛巳,初三立春,十八雨水]

建卯月辛亥[1],…。壬子[2],…。癸丑[3],…。乙丑[15],…。戊辰[18],…。庚午[20],…。壬申[22],…。[初一辛亥,初四惊蛰,十九春分]

建辰月壬午[3],…。甲午[5],…。戊申[19],…。[初一庚辰,初五清明,二十谷雨]

建巳月庚戌[1],…。壬子[3],…。甲寅[5],…。乙丑[16],…。大赦,改元年为宝应元年,复以正月为岁首,建巳月为四月。丙寅,…。[初一庚戌,初五甲寅立夏]。 - ^ The birthday is the day in each year that have the same date as the one on which someone was born. It is easy to confirm the birthday in the Chinese calendar for most people. But, if someone was born on the 30th of a month, his birthday is the last day of that month, and if someone is born in an intercalary month, his birthday is the day with the same date in the common month of the intercalary month.

- ^ The Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar and the Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar, and the birthday in the Chinese calendar is not same as in the Gregorian calendar always. so, there's a bias of +/-1 between the actual age in the Chinese calendar and in the Gregorian calendar. Thus, the nominal age in the Chinese calendar is 0~3 older than the actual age in the Gregorian calendar.

References

- ^ Sôma, Mitsuru; Kawabata, Kin-aki; Tanikawa, Kiyotaka (2004-10-25). "Units of Time in Ancient China and Japan". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 56 (5): 887–904. Bibcode:2004PASJ...56..887S. doi:10.1093/pasj/56.5.887. ISSN 0004-6264.

- ^ 海上 (2005). 《中國人的歲時文化》. 岳麓書社. p. 195. ISBN 7-80665-620-0.

- ^ 陳浩新. "「冷在三九,熱在三伏」". Educational Resources - Hong Kong Observatory.

- ^ "【典故】冬至進入數九寒天 九九消寒圖蘊藏智慧 | 神傳文化 | 大紀元". Epoch Times. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Days of the week in Japanese". CJVLang. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Mathematics of the Chinese calendar, pp. 29–30.

- ^ 《辽宁大学学报:哲社版》,2004/06,43~50页

- ^ Aslaksen, p.38.

- ^ Cohen (2012), p. 1, 4.

- ^ http://www.newsmth.net/bbsanc.php?path=%2Fgroups%2Fsci.faq%2FAstronomy%2Fbw%2Fall2%2Fbk37k%2FM.1275291864.z0&ap=353

- ^ Asiapac Editorial. (2004). Origins of Chinese Science and Technology. Translated by Yang Liping and Y.N. Han. Singapore: Asiapac Books Pte. Ltd. ISBN 981-229-376-0, p.132.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. (1959). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press., reprinted Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. (1986), pp. 109–110.

- ^ Ho, Peng Yoke. (2000). Li, Qi, and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41445-0. p. 105.

- ^ Restivo, Sal. (1992). Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 1-4020-0039-1. p. 32.

- ^ 孙中山:“临时大总统改历改元通电”,载《孙中山全集》(第2卷),中华书局1982年版,页5。

- ^ Mathematics of the Chinese calendar, pp. 28.

Further reading

- Cohen, Alvin (2012). "Brief Note: The Origin of the Yellow Emperor Era Chronology" (PDF). Asia Major. 25 (pt 2): 1–13.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ho, Kai-Lung (何凱龍) (2006). “The Political Power and the Mongolian Translation of the Chinese Calendar During the Yuan Dynasty”. Central Asiatic Journal 50 (1). Harrassowitz Verlag: 57–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41928409.

External links

- Calendars

- Chinese months

- Gregorian-Lunar calendar years (1901–2100)

- Chinese calendar and holidays

- Chinese calendar with Auspicious Events

- Calendar conversion

- 2000-year Chinese-Western calendar converter From 1 AD to 2100 AD. Useful for historical studies. To use, put the western year 年 month 月day 日in the bottom row and click on 執行.

- Western-Chinese calendar converter

- Rules