Clonazepam: Difference between revisions

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

===Warnings=== |

===Warnings=== |

||

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, will impair one's ability to drive or operate light or "heavy" machinery. The central nervous system depressing effects of the drug can be intensified by alcohol consumption. Benzodiazepines have been shown to cause both psychological and physical dependence. Patients physically dependent on clonazepam should be slowly titrated off under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional to reduce the intensity of withdrawal or rebound symptoms. |

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, will impair one's ability to drive or operate light or "heavy" machinery. The central nervous system depressing effects of the drug can be intensified by alcohol consumption. Benzodiazepines have been shown to cause both psychological and physical dependence. Patients physically dependent on clonazepam should be slowly titrated off under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional to reduce the intensity of withdrawal or rebound symptoms. A growing number of psychiatrists have spoken out against Clonazepam, and other Benzodiazapine-class medications, and have called for banning it for long-term use. |

||

==Pregnancy== |

==Pregnancy== |

||

Revision as of 19:18, 2 April 2010

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, I.M., I.V, sublingual |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | ~85% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 18–50 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.088 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

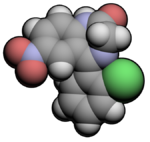

| Formula | C15H10ClN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 315.715 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clonazepam is a benzodiazepine derivative with anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant, and anxiolytic properties.[2] It is marketed by Roche under the trade-names Klonopin in the United States, and Ravotril in Chile. Other names like Rivotril or Rivatril are known throughout the large majority of the rest of the world. Clonazepam is generally considered to be among the long-acting benzodiazepines.[3] Clonazepam is a chlorinated derivative of nitrazepam[4] and therefore a nitrobenzodiazepine.[5]

Indications

Clonazepam may be prescribed for

- Epilepsy[6][7]

- Anxiety disorders

- Panic disorder[8]

- Initial treatment of mania or acute psychosis together with firstline drugs such as lithium, haloperidol or risperidone[9][10]

- Hyperekplexia[11]

- Many forms of parasomnia are sometimes treated with clonazepam.[12] Restless legs syndrome can be treated using clonazepam as a third line treatment option as the use of clonazepam is still investigational.[13][14] Bruxism also responds to clonazepam in the short-term.[15] Rapid eye movement behavior disorder responds well to low doses of clonazepam.[16]

- The treatment of acute and chronic akathisia[1][2]

The effectiveness of clonazepam in the short-term treatment of panic disorder has been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials. Some long-term trials have suggested a benefit of clonazepam for up to 3 years without the development of tolerance but these trials were not placebo controlled. Clonazepam is also effective in the management of acute mania.[17]

Clonazepam is sometimes used for refractory epilepsies; however, long-term prophylactic treatment of epilepsy has considerable limitations, the most notable ones being the loss of antiepileptic effects due to tolerance, which renders the drug useless with long-term use, and side-effects such as sedation, which is why clonazepam and benzodiazepines as a class should, in general, be prescribed only for the acute management of epilepsies.[18]

Clonazepam or diazepam has been found to be effective in the acute control of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. However, the benefits tended to be transient in many of the patients, and the addition of phenytoin for lasting control was required in these patients.[19]

In general, Clonazepam has been found to be ineffective in the control of infantile spasms.[20] Clonazepam is less effective and potent as an anticonvulsant in bringing infantile seizures under control compared with nitrazepam in the treatment of West syndrome, which is an age-dependent epilepsy affecting the very young. However, as with other epilepies treated with benzodiazepines, long-term therapy becomes ineffective with prolonged therapy, and the side effects of hypotonia and drowsiness are troublesome with clonazepam therapy; other antiepileptic agents are, therefore, recommended for long-term therapy, possibly Corticotropin (ACTH) or vigabatrin. Furthermore, Clonazepam is not recommended for widespread use in the management of seizures related to West syndrome.[21]

Clonazepam has shown itself to be highly effective as a short-term (3 weeks) adjunct to SSRI treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder and clinical depression in reducing SSRI side effects with the combination being superior to SSRI treatment alone in a study funded by the manufacturers of clonazepam, Hoffman LaRoche Inc.[22]

Availability

Clonazepam was approved in the United States as a generic drug in 1997 and is now manufactured and marketed by several companies.

Clonazepam is available in the U.S. as tablets (0.5, 1.0, and 2 mg) and orally disintegrating tablets (wafers) (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2 mg). In other countries, clonazepam is usually available as tablets (0.5 and 2 mg), orally disintegrating tablets (0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg) oral solution (drops, 2.5 mg/mL), as well as solution for injection or intravenous infusion, containing 1 mg clonazepam per ampoule (e.g. Rivotril inj.).

Side-effects

- Common

- Drowsiness[23]

- Impairment of cognition, judgment, or memory

- Irritability and aggression[24]

- Psychomotor agitation[25]

- Lack of motivation[26]

- Loss of libido

- Impaired motor function

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Diarrhea

- Cognitive impairments

- Increased sleepwalking (If used in treatment of sleepwalking)

- Auditory hallucinations

- Short-term memory loss

- Anterograde amnesia (common with higher doses)

- Some users report hangover-like symptoms of being drowsy, having a headache, being sluggish, and being irritable after waking up if the medication is taken before sleep. This is likely the result of the medication's long half-life, which continues to affect the user after waking up, as well as its disruption of the REM cycle.

- Occasional

- Serious dysphoria[27]

- Thrombocytopenia[28]

- Serious psychological and psychiatric side-effects[29][30]

- Induction of seizures[31][32] or increased frequency of seizures[33]

- Personality changes[34]

- Behavioural disturbances[35]

- Rare

- Psychosis[36]

- Incontinence[37][38][39]

- Liver damage[40]

- Paradoxical behavioural disinhibition[41][42][43] (most frequently in children, the elderly, and in persons with developmental disabilities)

- Rage

- Excitement

- Impulsivity

- Long term effects

The long term effects of clonazepam can include; depression, disinhibition and sexual dysfunction.[44]

- Withdrawal-related

- Anxiety, irritability, insomnia

- Panic attacks, tremor

- Seizures[45] similar to delirium tremens (with long-term use of excessive doses)

Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam can be very effective in controlling status epilepticus, but, when used for longer periods of time, serious side-effects may develop, such as interference with cognitive functions and behavior.[46] Many individuals treated on a long-term basis develop a form of dependence known as "low-dose dependence," as was shown in one double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 34 therapeutic low-dose benzodiazepine users — physiological dependence was demonstrated via flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal.[47] Use of alcohol or other CNS depressants while taking clonazepam greatly intensifies the effects (and side-effects) of the drug. Side-effects of the drug itself are generally benign, but sudden withdrawal after long-term use can cause severe, even fatal, symptoms.

Tolerance and withdrawal

Like all benzodiazepines, clonazepam is a benzodiazepine receptor agonist.[48][49]

Tolerance

Tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs in both animals and humans. In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs frequently.[50][51] Chronic use of benzodiazepines leads to the development of tolerance with a decrease of benzodiazepine binding sites. The degree of tolerance is more pronounced with clonazepam than with chlordiazepoxide.[52] In general, short-term therapy is more effective than long-term therapy with clonazepam for the treatment of epilepsy.[53] Many studies have found that tolerance develops to the anticonvulsant properties of clonazepam with chronic use, which limits its long term effectiveness as an anticonvulsant.[54]

Withdrawal

Abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal from clonazepam may result in the development of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, causing psychosis characterised by dysphoric manifestations, irritability, aggressiveness, anxiety, and hallucinations.[55][56][57] Sudden withdrawal may also induce the potentially life threatening condition status epilepticus. Antiepileptic drugs, benzodiazepines such as clonazepam in particular, should be reduced slowly and gradually when discontinuing the drug to reduce withdrawal effects.[34] Carbamazepine has been trialed in the treatment of clonazepam withdrawal and has been found to be ineffective in preventing clonazepam withdrawal status epilepticus from occurring.[58]

Special precautions

Caution in the elderly. Increased risk of impairments, falls and drug accumulation. Benzodiazepines also require special precaution if used in the pregnancy, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[59] Clonazepam is generally not recommended for use in elderly people for insomnia due to its high potency relative to other benzodiazepines.[60]

Caution in children. Clonazepam is not recommended for use in those under 18. Use in very young children may be especially hazardous. Of anticonvulsant drugs behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.[59][61]

Caution using high dosages of clonazepam. Doses higher than 0.5 – 1 mg per day are associated with significant sedation.[62]

Clonazepam may aggravate hepatic porphyria.[63][64]

Caution in chronic schizophrenia. A 1982 double blinded placebo controlled study found clonazepam increases violent behavior in individuals with chronic schizophrenia.[65]

Interactions

Clonazepam decreases the levels of carbamazepine,[66][67] and likewise its level is reduced by carbamazepine.[68] Clonazepam may affect levels of phenytoin (diphenylhydantoin) by decreasing,[66][69] or increasing.[70][71] In turn Phenytoin may lower clonazepam plasma levels, by increasing the speed of clonazepam clearance by approximately 50% and decreasing its half life by 31%.[72] Clonazepam increases the levels of primidone,[70] and phenobarbital.[73]

Warnings

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, will impair one's ability to drive or operate light or "heavy" machinery. The central nervous system depressing effects of the drug can be intensified by alcohol consumption. Benzodiazepines have been shown to cause both psychological and physical dependence. Patients physically dependent on clonazepam should be slowly titrated off under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional to reduce the intensity of withdrawal or rebound symptoms. A growing number of psychiatrists have spoken out against Clonazepam, and other Benzodiazapine-class medications, and have called for banning it for long-term use.

Pregnancy

There is some medical evidence of various malformations, e.g., cardiac or facial deformations, when used in early pregnancy, however the data is not conclusive. The data are also inconclusive on whether benzodiazepines such as clonazepam cause developmental deficits or decreases in IQ in the developing fetus when taken by the mother during pregnancy. Clonazepam when used late in pregnancy may result in the development of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate. Withdrawal symptoms from benzodiazepines in the neonate may include hypotonia, apnoeic spells, cyanosis and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress.[74]

The safety profile clonazepam during pregnancy is less clear than for other benzodiazepines and if benzodiazepines are indicated during pregnancy chlordiazepoxide and diazepam may be a safer choice. The use of clonazepam during pregnancy should only be used if the clinical benefits are believed to outweigh the clinical risks to the fetus. Caution is also required if clonazepam is used during breast feeding. Possible adverse effects of use of benzodiazepines such as clonazepam during pregnancy include; abortion, malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, functional deficits, floppy infant syndrome, carcinogenesis and mutagenesis. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome associated with benzodiazepines include hypertonia, hyperreflexia, restlessness, irritability, abnormal sleep patterns, inconsolable crying, tremors or jerking of the extremities, bradycardia, cyanosis, suckling difficulties, apnea, risk of aspiration of feeds, diarrhea and vomiting, and growth retardation. This syndrome can develop between 3 days and 3 weeks after birth and can have a duration of up to several months. The pathway by which clonazepam is metabolised is usually impaired in new borns. If clonazepam is used during pregnancy or breast feeding it is recommended that serum levels of clonazepam are monitored and signs of central nervous system depression and apnea are also monitored for. In many cases non-pharmacological treatments such as relaxation therapy, psychotherapy and avoidance of caffeine can be an effective and safer alternative to use of benzodiazepines for anxiety in pregnant women.[75]

Pharmacology

Clonazepam's primary mechanism of action is via modulating GABA function in the brain, via the benzodiazepine receptor, which, in turn, leads to enhanced GABAergic inhibition of neuronal firing. In addition clonazepam decreases the utilization of 5-HT (serotonin) by neurons[76][77] and has been shown to bind tightly to central type benzodiazepine receptors.[78] Because of its strong anxiolytic, anticonvulsant and euphoric properties, it is said to be among the class of "highly potent" benzodiazepines.[79] The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines are due to enhancement of synaptic GABA responses and inhibition of sustained high frequency repetitive firing.[80]

Benzodiazepines, including clonazepam, bind to mouse glial cell membranes with high affinity.[81][82] Clonazepam decreases release of acetylcholine in cat brain [83] and decreases prolactin release in rats.[84] Benzodiazepines inhibit cold-induced thyroid stimulating hormone (also known as TSH or thyrotropin) release.[85] Benzodiazepines acted via micromolar benzodiazepine binding sites as Ca2+ channel blockers and significantly inhibit depolarization-sensitive calcium uptake in experimentation on rat brain cell components. This has been conjectured as a mechanism for high-dose effects on seizures in the study.[86]

Mechanism of action

Clonazepam exerts its action by binding to the benzodiazepine site of the GABA receptors, which causes an enhancement of the electric effect of GABA binding on neurons, resulting in an increased influx of chloride ions into the neurons. This results in an inhibition of synaptic transmission across the central nervous system.[87][88] Benzodiazepines, however, do not have any effect on the levels of GABA in the brain.[89] Clonazepam has no effect on GABA levels and has no effect on gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase. Clonazepam does however affect glutamate decarboxylase activity. It differs insofar from other anticonvulsant drugs it was compared to in a study.[90] Benzodiazepine receptors are found in the central nervous system but are also found in a wide range of peripheral tissues such as longitudinal smooth muscle-myenteric plexus layer, lung, liver and kidney as well as mast cells, platelets, lymphocytes, heart and numerous neuronal and non-neuronal cell lines.[91]

Pharmacokinetics

Peak blood concentrations of 6.5–13.5 ng/mL were usually reached within 1–2 hours following a single 2 mg oral dose of micronized clonazepam in healthy adults. In some individuals, however, peak blood concentrations were reached at 4–8 hours.[92]

Clonazepam passes rapidly into the central nervous system, with levels in the brain corresponding with levels of unbound clonazepam in the blood serum.[93] Clonazepam plasma levels are very unreliable amongst patients. Plasma levels of clonazepam can vary as much as tenfold between different patients.[94]

Clonazepam is largely bound to plasma proteins.[95] Clonazepam passes through the blood-brain barrier easily, with blood and brain levels corresponding equally with each other. The elimination half life of clonazepam is between 20 – 80 hours. Clonazepam does not produce any pharmacologically active metabolites.[96] The metabolites of clonazepam include 7-aminoclonazepam, 7-acetaminoclonazepam and 3-hydroxy clonazepam.[97][98]

Overdose

An individual who has consumed too much clonazepam may display one or more of the following symptoms:

- Coma

- Hypotension

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Labored breathing

- Mental confusion

- Somnolence (difficulty staying awake)

- Nausea

Coma can be cyclic with the individual alternating from a comatose state to a hyperalert state of consciousness, as occurred in a 4-year-old boy who suffered an overdose of clonazepam.[99] The combination of clonazepam and certain barbiturates eg amobarbital at prescribed doses has resulted in a synergistic potentiation of the effects of each drug leading to serious respiratory depression.[100]

Detection in biological fluids

Clonazepam and 7-aminoclonazepam may be quantified in plasma, serum or whole blood in order to monitor compliance in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage. Both the parent drug and 7-aminoclonazepam are unstable in biofluids, and therefore specimens should be preserved with sodium fluoride, stored at the lowest possible temperature and analyzed quickly to minimize losses.[101]

Drug misuse

A 2006 US government study of nationwide Emergency Department (ED) visits conducted by SAMHSA found that sedative-hypnotics in the USA were the most frequently implicated pharmaceutical drug in ED visits. Benzodiazepines accounted for the majority of these. Clonazepam was the second most frequently implicated benzodiazepine in ED visits in the study.[citation needed] The study examined the number of times non-medical use of certain drugs were implicated in ED visits; the criteria for non-medical use in this study were purposefully broad, and include for example, drug abuse, accidental or intentional overdose, or adverse reactions resulting from legitimate use of the medication.[102]

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long term effects of benzodiazepines

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Cowen PJ (1981). "Ethyl beta-carboline carboxylate lowers seizure threshold and antagonizes flurazepam-induced sedation in rats". Nature. 290 (5801): 54–5. doi:10.1038/290054a0. PMID 6259533.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ Dreifuss FE (1975). "Serum clonazepam concentrations in children with absence seizures". Neurology. 25 (3): 255–8. PMID 1089913.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Robertson MD (1995). "Postmortem drug metabolism by bacteria". J Forensic Sci. 40 (3): 382–6. PMID 7782744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rossetti AO (2004). "Propofol treatment of refractory status epilepticus: a study of 31 episodes". Epilepsia. 45 (7): 757–63. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.01904.x. PMID 15230698.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ståhl Y, Persson A, Petters I, Rane A, Theorell K, Walson P (1983). "Kinetics of clonazepam in relation to electroencephalographic and clinical effects". Epilepsia. 24 (2): 225–31. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04883.x. PMID 6403345.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cloos, Jean-Marc (2005). "The Treatment of Panic Disorder". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 18 (1): 45–50. PMID 16639183. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ Curtin F, Schulz P (2004). "Clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania: a Bayesian meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 78 (3): 201–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00317-8. PMID 15013244.

- ^ Gillies D, Beck A, McCloud A, Rathbone J, Gillies D (2005). "Benzodiazepines alone or in combination with antipsychotic drugs for acute psychosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003079. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003079.pub2. PMID 16235313.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhou, L.; Chillag, KL.; Nigro, MA. (2002). "Hyperekplexia: a treatable neurogenetic disease". Brain Dev. 24 (7): 669–74. doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(02)00095-5. PMID 12427512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schenck, CH.; Arnulf, I.; Mahowald, MW. (2007). "Sleep and sex: what can go wrong? A review of the literature on sleep related disorders and abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences". Sleep. 30 (6): 683–702. PMC 1978350. PMID 17580590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "[Restless legs syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Opinion of Brazilian experts]". Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 65 (3A): 721–7. 2007. PMID 17876423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trenkwalder, C.; Hening, WA.; Montagna, P.; Oertel, WH.; Allen, RP.; Walters, AS.; Costa, J.; Stiasny-Kolster, K.; Sampaio, C. (2008). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice" (PDF). Mov Disord. 23 (16): 2267–302. doi:10.1002/mds.22254. PMID 18925578.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Huynh, NT.; Rompré, PH.; Montplaisir, JY.; Manzini, C.; Okura, K.; Lavigne, GJ. (2006). "Comparison of various treatments for sleep bruxism using determinants of number needed to treat and effect size". Int J Prosthodont. 19 (5): 435–41. PMID 17323720.

- ^ Ferini-Strambi, L.; Zucconi, M. (2000). "REM sleep behavior disorder". Clin Neurophysiol. 111 Suppl 2: S136–40. PMID 10996567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nardi, AE.; Perna, G. (2006). "Clonazepam in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: an update". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 21 (3): 131–42. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000194379.65460.a6. PMID 16528135.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Isojärvi, JI (1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". J Intellect Disabil Res. 42 (1): 80–92. PMID 10030438.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tomson T (1986). "Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: high incidence of complex partial status". Epilepsia. 27 (3): 276–85. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03540.x. PMID 3698940.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hrachovy RA, Frost JD Jr, Kellaway P, Zion TE (1983). "Double-blind study of ACTH vs prednisone therapy in infantile spasms". J Pediatr. 103 (4): 641–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(83)80606-4. PMID 6312008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Djurić, M (2001). "[West syndrome--new therapeutic approach]". Srp Arh Celok Lek. 129 (1): 72–7. PMID 15637997.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Smith WT, Londborg PD, Glaudin V, Painter JR (1998). "Short-term augmentation of fluoxetine with clonazepam in the treatment of depression: a double-blind study". Am J Psychiatry. 155 (10): 1339–45. PMID 9766764.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stacy, M. (2002). "Sleep disorders in Parkinson's disease: epidemiology and management". Drugs Aging. 19 (10): 733–9. doi:10.2165/00002512-200219100-00002. PMID 12390050.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Lander CM (1979). "Some aspects of the clinical use of clonazepam in refractory epilepsy". Clin Exp Neurol. 16: 325–32. PMID 121707.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sorel L (1981). "Comparative trial of intravenous lorazepam and clonazepam im status epilepticus". Clin Ther. 4 (4): 326–36. PMID 6120763.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wollman M (1985). "A hypernychthemeral sleep-wake syndrome: a treatment attempt". Chronobiol Int. 2 (4): 277–80. doi:10.3109/07420528509055890. PMID 3870855.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sjö O (1975). "Pharmacokinetics and side-effects of clonazepam and its 7-amino-metabolite in man". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 8 (3–4): 249–54. doi:10.1007/BF00567123. PMID 1233220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Veall RM (1975). "Letter: Thrombocytopenia during treatment with clonazepam" (PDF). Br Med J. 4 (5994): 462. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5994.462. PMC 1675341. PMID 1192127.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hansson O (1976). "[Serious psychological symptoms caused by clonazepam]". Lakartidningen. 73 (13): 1209–10. PMID 1263638.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barfod S (1977). "[Severe psychiatric side effects of clonazepam treatment. 2 cases]". Ugeskr Laeger. 139 (41): 2450. PMID 906141.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alvarez N (1981). "Epileptic seizures induced by clonazepam". Clin Electroencephalogr. 12 (2): 57–65. PMID 7237847.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ishizu T, Chikazawa S, Ikeda T, Suenaga E (1988). "[Multiple types of seizure induced by clonazepam in an epileptic patient]". No to Hattatsu (in Japanese). 20 (4): 337–9. PMID 3214607.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bang F (1976). "Clonazepam in the treatment of epilepsy. A clinical long-term follow-up study". Epilepsia. 17 (3): 321–4. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1976.tb03410.x. PMID 824124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bruni J (1979). "Recent advances in drug therapy for epilepsy". Can Med Assoc J (PDF). 120 (7): 817–24. PMC 1818965. PMID 371777.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "clonepi" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Rosenfeld WE, Beniak TE, Lippmann SM, Loewenson RB (1987). "Adverse behavioral response to clonazepam as a function of Verbal IQ-Performance IQ discrepancy". Epilepsy Res. 1 (6): 347–56. doi:10.1016/0920-1211(87)90059-3. PMID 3504409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ White MC (1982). "Psychosis associated with clonazepam therapy for blepharospasm". J Nerv Ment Dis. 170 (2): 117–9. PMID 7057171.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Williams A (1979). "Clonazepam-induced incontinence". Ann Neurol. 6 (1): 86. doi:10.1002/ana.410060127. PMID 507767.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sandyk R (August 13, 1983). "Urinary incontinence associated with clonazepam therapy". S Afr Med J. 64 (7): 230. PMID 6879368.

- ^ Anders RJ (1985). "Overflow urinary incontinence due to carbamazepine". J Urol. 134 (4): 758–9. PMID 4032590.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Olsson R, Zettergren L (1988). "Anticonvulsant-induced liver damage". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 83 (5): 576–7. PMID 3364416.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ van der Bijl P, Roelofse JA (1991). "Disinhibitory reactions to benzodiazepines: a review". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 49 (5): 519–23. doi:10.1016/0278-2391(91)90180-T. PMID 2019899.

- ^ Binder RL (1987). "Three case reports of behavioral disinhibition with clonazepam". Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 9 (2): 151–3. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(87)90028-4. PMID 3569889.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kubacki A (1987). "Sexual disinhibition on clonazepam". Can J Psychiatry. 32 (7): 643–5. PMID 3676996.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JF (1987). "Clonazepam: new uses and potential problems". J Clin Psychiatry. 48 Suppl: 50–6. PMID 2889724.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lockard JS (1979). "Clonazepam in a focal-motor monkey model: efficacy, tolerance, toxicity, withdrawal, and management". Epilepsia. 20 (6): 683–95. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1979.tb04852.x. PMID 115680.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vining EP (1986). "Use of barbiturates and benzodiazepines in treatment of epilepsy". Neurol Clin. 4 (3): 617–32. PMID 3528811.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernik MA (1998). "Stressful reactions and panic attacks induced by flumazenil in chronic benzodiazepine users". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 146–50. PMID 9694026.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Adjeroud, S; Tonon, Mc; Leneveu, E; Lamacz, M; Danger, Jm; Gouteux, L; Cazin, L; Vaudry, H (1987). "The benzodiazepine agonist clonazepam potentiates the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid on alpha-MSH release from neurointermediate lobes in vitro". Life sciences. 40 (19): 1881–7. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(87)90046-4. PMID 3033417.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yokota, K; Tatebayashi, H; Matsuo, T; Shoge, T; Motomura, H; Matsuno, T; Fukuda, A; Tashiro, N (2002). "The effects of neuroleptics on the GABA-induced Cl- current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: differences between some neuroleptics" (PDF). British journal of pharmacology. 135 (6): 1547–55. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704608. PMC 1573270. PMID 11906969.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Loiseau P (1983). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy]". Encephale. 9 (4 Suppl 2): 287B–292B. PMID 6373234.

- ^ Scherkl R, Scheuler W, Frey HH (1985). "Anticonvulsant effect of clonazepam in the dog: development of tolerance and physical dependence". Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 278 (2): 249–60. PMID 4096613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crawley JN (1982). "Chronic clonazepam administration induces benzodiazepine receptor subsensitivity". Neuropharmacology. 21 (1): 85–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(82)90216-7. PMID 6278355.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bacia T (1980). "Clonazepam in the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy: a clinical short- and long-term follow-up study". Monogr Neural Sci. 5: 153–9. PMID 7033770.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Browne TR (1976). "Clonazepam. A review of a new anticonvulsant drug". Arch Neurol. 33 (5): 326–32. PMID 817697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sironi VA (1984). "Clonazepam withdrawal syndrome". Acta Neurol (Napoli). 6 (2): 134–9. PMID 6741654.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sironi VA (1979). "Interictal acute psychoses in temporal lobe epilepsy during withdrawal of anticonvulsant therapy". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 42 (8): 724–30. doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.8.724. PMC 490305. PMID 490178.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jaffe R (1986). "Clonazepam withdrawal psychosis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 6 (3): 193. doi:10.1097/00004714-198606000-00021. PMID 3711371.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sechi GP (1984). "Failure of carbamazepine to prevent clonazepam withdrawal statusepilepticus". Ital J Neurol Sci. 5 (3): 285–7. doi:10.1007/BF02043959. PMID 6500901.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wolkove, N.; Elkholy, O.; Baltzan, M.; Palayew, M. (2007). "Sleep and aging: 2. Management of sleep disorders in older people". CMAJ. 176 (10): 1449–54. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070335. PMC 1863539. PMID 17485699.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trimble MR (1988). "Children of school age: the influence of antiepileptic drugs on behavior and intellect". Epilepsia. 29 Suppl 3: S15–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05805.x. PMID 3066616.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hollister LE (1975). "Dose-ranging studies of clonazepam in man". Psychopharmacol Commun. 1 (1): 89–92. PMID 1223993.

- ^ Bonkowsky HL (1980). "Seizure management in acute hepatic porphyria: risks of valproate and clonazepam". Neurology. 30 (6): 588–92. PMID 6770287.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reynolds NC Jr (1981). "Safety of anticonvulsants in hepatic porphyrias". Neurology. 31 (4): 480–4. PMID 7194443.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Karson CN (1982). "Clonazepam treatment of chronic schizophrenia: negative results in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Am J Psychiatry. 139 (12): 1627–8. PMID 6756174.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lander CM (1975). "Interactions between anticonvulsants". Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 12: 111–6. PMID 2912.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pippenger CE (1987). "Clinically significant carbamazepine drug interactions: an overview". Epilepsia. 28 (Suppl 3): S71–6. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb05781.x. PMID 3319544.

- ^ Lai AA, Levy RH (1978). "Time-course of interaction between carbamazepine and clonazepam in normal man". Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 24 (3): 316–23. PMID 688725.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Saavedra IN (1985). "Phenytoin/clonazepam interaction". Ther Drug Monit. 7 (4): 481–4. doi:10.1097/00007691-198512000-00022. PMID 4082246.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Windorfer A Jr (1977). "Drug interactions during anticonvulsant therapy in childhood: diphenylhydantoin, primidone, phenobarbitone, clonazepam, nitrazepam, carbamazepin and dipropylacetate". Neuropadiatrie. 8 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1091502. PMID 321985.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Windorfer A (1977). "[Laboratory controls in long-term treatment with anticonvulsive drugs (author's transl)]". Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 125 (3): 122–8. PMID 323695.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Khoo KC (1980). "Influence of phenytoin and phenobarbital on the disposition of a single oral dose of clonazepam". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 28 (3): 368–75. PMID 7408397.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bendarzewska-Nawrocka B (1980). "[Relationship between blood serum luminal and diphenylhydantoin level and the results of treatment and other clinical data in drug-resistant epilepsy]". Neurol Neurochir Pol. 14 (1): 39–45. PMID 7374896.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McElhatton PR (1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reprod Toxicol. 8 (6): 461–75. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Iqbal, MM.; Sobhan, T.; Ryals, T. (2002). "Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant". Psychiatr Serv. 53 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.39. PMID 11773648.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Meldrum BS (1986). "Drugs acting on amino acid neurotransmitters". Adv Neurol. 43: 687–706. PMID 2868623.

- ^ Jenner P (1986). "Mechanism of action of clonazepam in myoclonus in relation to effects on GABA and 5-HT". Adv Neurol. 43: 629–43. PMID 2418652.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gavish M (1985). "Solubilization of peripheral benzodiazepine-binding sites from rat kidney" (PDF). J Neurosci. 5 (11): 2889–93. PMID 2997409.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chouinard G (2004). "Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound". J Clin Psychiatry. 65 Suppl 5: 7–12. PMID 15078112.

- ^ Macdonald RL (1986). "Anticonvulsant drugs: mechanisms of action". Adv Neurol. 44: 713–36. PMID 2871724.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tardy M (1981). "Benzodiazepine receptors on primary cultures of mouse astrocytes". J Neurochem. 36 (4): 1587–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb00603.x. PMID 6267195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gallager DW (1981). "{3H}Diazepam binding in mammalian central nervous system: a pharmacological characterization". J Neurosci (PDF). 1 (2): 218–25. PMID 6267221.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Petkov V (1982). "Effects of some benzodiazepines on the acetylcholine release in the anterior horn of the lateral cerebral ventricle of the cat". Acta Physiol Pharmacol Bulg. 8 (3): 59–66. PMID 6133407.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Grandison L (1982). "Suppression of prolactin secretion by benzodiazepines in vivo". Neuroendocrinology. 34 (5): 369–73. doi:10.1159/000123330. PMID 6979001.

- ^ Camoratto AM (18 April 1983). "Inhibition of cold-induced TSH release by benzodiazepines". Brain Res. 265 (2): 339–43. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(83)90353-0. PMID 6405978.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Taft WC (1984). "Micromolar-affinity benzodiazepine receptors regulate voltage-sensitive calcium channels in nerve terminal preparations" (PDF). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (PDF). 81 (10): 3118–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.10.3118. PMC 345232. PMID 6328498.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Skerritt JH (May 6, 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". Eur J Pharmacol. 89 (3–4): 193–8. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. PMID 6135616.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lehoullier PF, Ticku MK (1987). "Benzodiazepine and beta-carboline modulation of GABA-stimulated 36Cl-influx in cultured spinal cord neurons". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 135 (2): 235–8. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(87)90617-0. PMID 3034628.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Varotto M (1981). "[Pharmacological influences on the brain level and transport of GABA. I) Effect of various antipileptic drugs on brain levels of GABA]". Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 57 (8): 904–8. PMID 7272065.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Battistin L, Varotto M, Berlese G, Roman G (1984). "Effects of some anticonvulsant drugs on brain GABA level and GAD and GABA-T activities". Neurochem Res. 9 (2): 225–31. doi:10.1007/BF00964170. PMID 6429560.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hullihan JP (1983). "The binding of {3H}-diazepam to guinea-pig ileal longitudinal muscle and the in vitro inhibition of contraction by benzodiazepines". Br J Pharmacol (PDF). 78 (2): 321–7. PMID 6131717.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Monograph - Clonazepam -- Pharmacokinetics". Medscape. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Parry GJ (1976). "An animal model for the study of drugs in the central nervous system". Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 13: 83–8. PMID 1029011.

- ^ Gerna M (January 21, 1976). "A simple and sensitive gas chromatographic method for the determination of clonazepam in human plasma". J Chromatogr. 116 (2): 445–50. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)89915-X. PMID 1245581.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tokola RA (1983). "Pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs". Acta neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 97: 17–27. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb01532.x. PMID 6143468.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG, Shader RI (1987). "Clonazepam pharmacokinetics, brain uptake, and receptor interactions". J Clin Psychiatry. 48 Suppl: 4–11. PMID 2822672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ebel S (February 27, 1977). "[Studies on the detection of clonazepam and its main metabolites considering in particular thin-layer chromatography discrimination of nitrazepam and its major metabolic products (author's transl)]". Arzneimittelforschung. 27 (2): 325–37. PMID 577149.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Edelbroek PM (1978). "Improved micromethod for determination of underivatized clonazepam in serum by gas chromatography" (PDF). Clinical chemistry (PDF). 24 (10): 1774–7. PMID 699288.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Welch TR (1977). "Clonazepam overdose resulting in cyclic coma". Clin Toxicol. 10 (4): 433–6. doi:10.3109/15563657709046280. PMID 862377.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Honer WG (1986). "Respiratory failure after clonazepam and amobarbital" (PDF). Am J Psychiatry. 143 (11): 1495. PMID 3777263.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 335-337.

- ^ United States Government (2006). "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Carlos, Jean-Marc: The Treatment of Panic Disorder http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/497207

- Rx-List - Clonazepam

- Poisons Information Monograph - Clonazepam

- FDA prescription insert