Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 February 1821 Bristol, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 31 May 1910 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | British and American |

| Alma mater | Geneva Medical College |

| Occupation | |

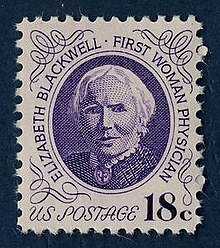

Elizabeth Blackwell (3 February 1821 – 31 May 1910) was a British-born physician, notable as the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, as well as the first woman on the UK Medical Register. She was the first woman to graduate from medical school, a pioneer in promoting the education of women in medicine in the United States, and a social and moral reformer in both the United States and in the United Kingdom. Her sister Emily was the third woman in the US to get a medical degree.

Early life

Elizabeth was born in a house on Dicksons Street in Bristol, Gloucestershire, England, to Samuel Blackwell, a sugar refiner, and his wife Hannah (Lane) Blackwell.[1] She had two older siblings, Anna and Marian, and would eventually have six younger siblings: Samuel (married Antoinette Brown), Henry (married Lucy Stone), Emily (third woman in the U.S. to get a medical degree), Sarah, John and George. Four maiden aunts, Barbara, Ann, Lucy and Mary, also lived with the Blackwells during Blackwell's childhood. Blackwell's earliest memories were of her time living at a house on 1 Wilson Street, off Portland Square, Bristol.[2]

Her childhood at Wilson Street was a happy one.[2] Blackwell especially remembered the positive and loving influence of her father. Samuel Blackwell was somewhat liberal in his attitudes towards, not only child rearing, but also religion and social ideologies. For example, rather than beating his children for bad behavior, Barbara Blackwell recorded their trespasses in a black book. If the offences accumulated, the children might be exiled to the attic during dinner.[3] However, Blackwell's father was by no means lax in the education of his children. Samuel Blackwell was a Congregationalist, and exerted a strong influence over the religious and practical education of his children. He believed that each child, including his girls, should be given the opportunity for unlimited development of their talents and gifts. Blackwell had not only a governess, but also private tutors to supplement her intellectual development. As a result, she was rather socially isolated from all but her family as she grew up.[1]

Early adulthood

The Blackwells' financial situation was unfortunate. Pressed by financial need, the sisters Anna, Marian and Elizabeth started a school, The Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies, which provided instruction in most if not all subjects, and charged for tuition, room and board. The school was not terribly innovative in its education methods – it was merely a source of income for the Blackwell sisters.[4] Blackwell's abolition work took a back seat during these years, most likely due to the Academy.[1]

Blackwell converted to Episcopalianism, probably due to her sister Anna's influence, in December 1838, becoming an active member of St. Paul's Episcopal Church. However, William Henry Channing's arrival in 1839 to Cincinnati changed her mind. Channing, a charismatic Unitarian minister, introduced the ideas of transcendentalism to Blackwell, who started attending the Unitarian Church. A conservative backlash from the Cincinnati community ensued, and as a result, the Academy lost many pupils and was abandoned in 1842. Blackwell began teaching private pupils.[1]

Channing's arrival renewed Blackwell's interests in education and reform. She worked at intellectual self-improvement: studying art, attending various lectures, writing short stories and attending various religious services in all denominations (Quaker, Millerite, Jewish). In the early 1840s, she began to articulate thoughts about women's rights in her diaries and letters, and participated in the Harrison political campaign of 1840.[1]

In 1844, with the help of her sister Anna, Blackwell procured a teaching job that paid $400 per year in Henderson, Kentucky. Although she was pleased with her class, she found the accommodations and schoolhouse lacking. What disturbed her most was that this was her first real encounter with the realities of slavery. "Kind as the people were to me personally, the sense of justice was continually outraged; and at the end of the first term of engagement I resigned the situation."[5] She returned to Cincinnati only half a year later, resolved to find a more stimulating means of spending her life.[2]

Education

Pursuit of medical education

Once again, through her sister Anna, Blackwell procured a job, this time teaching music at an academy in Asheville, North Carolina, with the goal of saving up the $3,000 necessary for her medical school expenses. In Asheville Blackwell lodged with a respected Reverend John Dickson, who happened to have been a physician before he became a clergyman. Dickson approved of Blackwell's career aspirations, and allowed her to use the medical books in his library to study. During this time, Blackwell soothed her own doubts about her choice and her loneliness with deep religious contemplation. She also renewed her antislavery interests – starting a slave Sunday school that was not ultimately successful.[1]

Dickson's school closed down soon after, and Blackwell moved to the residence of Reverend Dickson's brother, Samuel Henry Dickson, a prominent Charleston physician. She started teaching in 1846 at a boarding school in Charleston run by a Mrs. Du Pré. With the help of Reverend Dickson's brother, Blackwell inquired into the possibility of medical study via letters, with no favourable responses. In 1847, Blackwell left Charleston for Philadelphia and New York, with the aim of personally investigating the opportunities for medical study. Blackwell's greatest wish was to be accepted into one of the Philadelphia medical schools.[2]

"My mind is fully made up. I have not the slightest hesitation on the subject; the thorough study of medicine, I am quite resolved to go through with. The horrors and disgusts I have no doubt of vanquishing. I have overcome stronger distastes than any that now remain, and feel fully equal to the contest. As to the opinion of people, I don't care one straw personally; though I take so much pains, as a matter of policy, to propitiate it, and shall always strive to do so; for I see continually how the highest good is eclipsed by the violent or disagreeable forms which contain it."[5]

Upon reaching Philadelphia, Blackwell boarded with Dr. William Elder, and studied anatomy privately with Dr. Jonathan M. Allen as she attempted to get her foot in the door at any medical school in Philadelphia.[1] She was met with resistance almost everywhere. Most physicians recommended that she either go to Paris to study, or that she take up a disguise as a man to study medicine. The main reasons offered for her rejection were that (1) she was a woman and therefore intellectually inferior, and (2) she might actually prove equal to the task, prove to be competition, and that she could not expect them to "furnish [her] with a stick to break our heads with". Out of desperation, she applied to twelve "country schools".[2]

Medical education in the United States

In October 1847, Blackwell was accepted as a medical student by Hobart College, then called Geneva Medical College, located in upstate New York. Her acceptance was a near-accident. The dean and faculty, usually responsible for evaluating an applicant for matriculation, were not able to make a decision due to the special nature of Blackwell's case. They put the issue up to vote by the 150 male students of the class with the stipulation that if one student objected, Blackwell would be turned away. The young men voted unanimously to accept her.[6][7]

When Blackwell arrived at the college, she was rather nervous. Nothing was familiar – the surroundings, the students and the faculty. She did not even know where to get her books. However, she soon found herself at home in medical school.[1] While she was at school, she was looked upon as an oddity by the townspeople of Geneva. She also rejected suitors and friends alike, preferring to isolate herself. In the summer between her two terms at Geneva, she returned to Philadelphia, stayed with Dr. Elder, and applied for medical positions in the area to gain clinical experience. The Guardians of the Poor, the city commission that ran Blockley Almshouse, granted her permission to work there, albeit not without some struggle. Blackwell slowly gained acceptance at Blockley, although some young resident physicians still would walk out and refuse to assist her in diagnosing and treating her patients. During her time here, Blackwell gained valuable clinical experience, but was appalled by the syphilitic ward and those afflicted with typhus. Her graduating thesis at Geneva Medical College ended up being on the topic of typhus. The conclusion of this thesis linked physical health with socio-moral stability – a link that foreshadows her later reform work.[1]

On January 23, 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to achieve a medical degree in the United States. The local press reported her graduation favourably, and when the dean, Dr. Charles Lee, conferred her degree, he stood up and bowed to her.[8]

Medical education in Europe

In April 1849, Blackwell made the decision to continue her studies in Europe. She visited a few hospitals in Britain and then headed to Paris. Just like in America, she was rejected from many hospitals due to her gender. In June, Blackwell enrolled at La Maternité; a "lying-in" hospital,[6] under the condition that she would be treated as a student midwife, not a physician. She made the acquaintance of Hippolyte Blot, a young resident physician at La Maternité. She gained much medical experience through his mentorship and training. By the end of the year, Paul Dubois, the foremost obstetrician in his day, had voiced his opinion that she would make the best obstetrician in the United States, male or female.[2]

On 4 November 1849, when Blackwell was treating an infant with ophthalmia neonatorum, she spurted some contaminated solution into her own eye accidentally, and contracted the infection. She lost sight in her left eye, causing her to have her eye surgically extracted and thus lost all hope of becoming a surgeon.[2] After a period of recovery, she enrolled at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London in 1850. She regularly attended James Paget's lectures. She made a good impression there, although she did meet some opposition when she tried to observe the wards.[1]

Feeling that the prejudice against women in medicine was not as strong there, Blackwell returned to New York City in 1851 with the hope of establishing her own practice.[1]

Career

Medical career in the United States

Stateside, Blackwell was faced with adversity, but did manage to get some media support from entities such as the New-York Tribune.[2] She had very few patients, a situation she attributed to the stigma of women doctors as abortionists. In 1852, she began delivering lectures and published The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls, her first work, a volume about the physical and mental development of girls. Although Elizabeth herself pursued a career and never married or carried a child, this treatise ironically concerned itself with the preparation of young women for motherhood.[1]

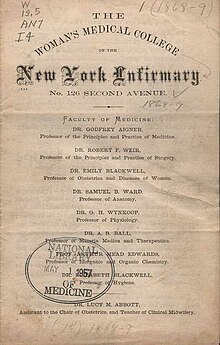

In 1853, Blackwell established a small dispensary near Tompkins Square. She also took Marie Zakrzewska, a Polish woman pursuing a medical education, under her wing, serving as her preceptor in her pre-medical studies. In 1857, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, along with Blackwell and her sister Emily, who had also obtained a medical degree, expanded Blackwell's original dispensary into the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. Women served on the board of trustees, on the executive committee and as attending physicians. The institution accepted both in and outpatients and served as a nurse's training facility. The patient load doubled in the second year.[1]

Civil War efforts

When the American Civil War broke out, the Blackwell sisters aided in nursing efforts. Blackwell sympathized heavily with the North due to her abolitionist roots, and even went so far as to say she would have left the country if the North had compromised on the subject of slavery.[9] However, Blackwell did meet with some resistance on the part of the male-dominated United States Sanitary Commission. The male physicians refused to help with the nurse education plan if it involved the Blackwells. Still, the New York Infirmary managed to work with Dorothea Dix to train nurses for the Union effort.[9]

Medical career at home and abroad

Blackwell made several trips back to Britain to raise funds and to try to establish a parallel infirmary project there. In 1858, under a clause in the Medical Act 1858 that recognised doctors with foreign degrees practicing in Britain before 1858, she was able to become the first woman to have her name entered on the General Medical Council's medical register (1 January 1859).[10] She also became a mentor to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson during this time. By 1866, nearly 7,000 patients were being treated per year at the New York Infirmary, and Blackwell was needed back in the United States. The parallel project fell through, but in 1868, a medical college for women adjunct to the infirmary was established. It incorporated Blackwell's innovative ideas about medical education – a four-year training period with much more extensive clinical training than previously required.[1]

At this point, a rift occurred between Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell. They both had extremely headstrong personalities, and a power struggle over the management of the infirmary and medical college ensued.[1] Elizabeth, feeling slightly alienated by the United States women's medical movement, left for Britain to try to establish medical education for women there. In July 1869, she sailed for Britain.[1]

In 1874, Blackwell established a women's medical school in London with Sophia Jex-Blake, who had been a student at the New York Infirmary years earlier. Blackwell had doubts about Jex-Blake, and thought that she was dangerous, belligerent and tactless.[11] Nonetheless, Blackwell became deeply involved with the school, and it opened in 1874 as the London School of Medicine for Women, with the primary goal of preparing women for the licensing exam of Apothecaries Hall. Blackwell vehemently opposed the use of vivisections in the laboratory of the school.[1]

After the establishment of the school, Blackwell lost much of her authority to Jex-Blake, and was elected as a lecturer in midwifery. She resigned this position in 1877, officially retiring from her medical career.[1]

While Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, her student Mary Putnam Jacobi focused on curing disease. At a deeper level of disagreement, Blackwell felt that women would succeed in medicine because of their humane female values, but Jacobi believed that women should participate as the equals of men in all medical specialties.[12]

Time in Europe – social and moral reform

After leaving for Britain in 1869, Blackwell diversified her interests, and was active both in social reform and authorship. She co-founded the National Health Society in 1871. She perceived herself as a wealthy gentlewoman who had the leisure to dabble in reform and in intellectual activities – the income from her American investments supported her.[1] She was rather occupied with her social status, and her friend, Barbara Bodichon helped introduce Blackwell into her circles. She travelled across Europe many times during these years, in England, France, Wales, Switzerland and Italy.[1]

Her greatest period of reform activity was after her retirement from the medical profession, from 1880–1895. Blackwell was interested in a great number of reform movements – mainly moral reform, sexual purity, hygiene and medical education, but also preventative medicine, sanitation, eugenics, family planning, women's rights, associationism, Christian socialism, medical ethics and antivivisection – none of which ever came to real fruition.[1] She switched back and forth between many different reform organisations, trying to maintain a position of power in each. Blackwell had a lofty, elusive and ultimately unattainable goal: evangelical moral perfection. All of her reform work was along this thread. She even contributed heavily to the founding of two utopian communities: Starnthwaite and Hadleigh in the 1880s.[1]

She believed that the Christian morality ought to play as large a role as scientific inquiry in medicine and that medical schools ought to instruct students in this basic truth. She also was antimaterialist and did not believe in vivisections, inoculation, vaccines or germ theory, instead subscribing to more spiritual healing methods. She believed that disease came from moral impurity, not from microbes.[13]

As such, she campaigned heavily against licentiousness, prostitution and contraceptives, arguing instead for the rhythm method.[14] She campaigned against the Contagious Diseases Acts, arguing that it was a pseudo-legalisation of prostitution. Her 1878 Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of their Children was an essay on prostitution and marriage arguing against the Contagious Diseases Acts. She was conservative in all senses except that she believed women to have sexual passions equal to those of men, and that men and women were equally responsible for controlling those passions.[15] Others of her time believed women to have little if any sexual passion, and placed the responsibility of moral policing squarely on the shoulders of the woman. The book was controversial, being rejected by 12 publishers, before being printed by Hatchard and Company. The proofs for the original edition were destroyed by a member of the publisher's board and a change of title was required for a new edition to be printed.

Personal life

Friends and family

Blackwell was well connected, both in the United States and in the United Kingdom. She exchanged letters with Lady Byron about women's rights issues, and became very close friends with Florence Nightingale, with whom she discussed opening and running a hospital together. She remained lifelong friends with Barbara Bodichon, and met Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1883. She was close with her family, and visited her brothers and sisters whenever she could during her travels.[1]

However, Blackwell had a very strong personality, and was often quite acerbic in her critique of others, especially of other women. Blackwell had a falling out with Florence Nightingale after Nightingale returned from the Crimean War. Nightingale wanted Blackwell to turn her focus to training nurses, and could not see the legitimacy of training female physicians.[9] After that, Blackwell's comments upon Florence Nightingale's publications were often highly critical.[16] She was also highly critical of many of the women's reform and hospital organisations in which she played no role, calling some of them "quack auspices".[17] Blackwell also did not get along well with her more stubborn sisters Anna and Emily, or with the women physicians she mentored after they established themselves (Marie Zakrzewska, Sophia Jex-Blake and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson). Among women at least, Blackwell was very assertive and found it difficult to play a subordinate role.[1]

Kitty Barry

In 1856, when Blackwell was establishing the New York Infirmary, she adopted Katherine "Kitty" Barry, an Irish orphan from the House of Refuge on Randall's Island. Diary entries at the time show that she adopted Barry half out of loneliness and a feeling of obligation, and half out of a utilitarian need for domestic help.[18] Barry was brought up as a half-servant, half-daughter.[1]

Blackwell did provide for Barry's education. She even instructed Barry in gymnastics as a trial for the theories outlined in her publication, The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls.[9] However, Blackwell never permitted Barry to develop her own interests. She didn't make an effort to introduce Barry to young men or women of her age. Barry herself was rather shy, awkward and self-conscious about her slight deafness.[1] Barry followed Blackwell during her many trans-Atlantic moves, during her furious house hunt between 1874 and 1875, during which they moved six times, and finally to Blackwell's final home, Rock House, a small house off Exmouth Place in Hastings, Sussex, in 1879.[1]

Barry stayed with Blackwell all her life. After Blackwell's death, Barry stayed at Rock House, and then moved to Kilmun in Argyllshire, Scotland, where Blackwell was buried in the churchyard of St Munn's Parish Church. In 1920, she moved in with the Blackwells and took the Blackwell name. On her deathbed, in 1930, Barry called Blackwell her "true love", and requested that her ashes be buried with those of Elizabeth.[19]

Private life

None of the five Blackwell sisters ever married. Elizabeth thought courtship games were foolish early in her life, and prized her independence.[1] When commenting on the young men trying to court her during her time in Kentucky, she said: "...do not imagine I am going to make myself a whole just at present; the fact is I cannot find my other half here, but only about a sixth, which would not do."[2] Even during her time at Geneva Medical College, she rejected advances from a few suitors.[2]

There was one major controversy, however, in Blackwell's life: Alfred Sachs, a Jewish man of 26 from Virginia. He was very close with both Kitty Barry and Blackwell, and it was widely believed in 1876 that he was a suitor for Barry, who was 29 at the time. The reality was that Blackwell and Sachs were very close, so much so that Barry felt uncomfortable being around the two of them. Sachs was very interested in Blackwell, then 55 years old. Barry was in love with Sachs, and was mildly jealous of Blackwell.[20] Blackwell thought that Sachs lived a life of dissipation and believed that she could reform him. In fact, the majority of her 1878 publication Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of the Children was based on her conversations with Sachs. Blackwell stopped correspondence with Alfred Sachs after the publication of her book.[1]

Last years and death

Blackwell, in her later years, was still relatively active. In 1895, she published her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. It was not very successful, selling fewer than 500 volumes.[1] After this publication, Blackwell slowly relinquished her public reform presence, and spent more time traveling. She visited the United States in 1906 and took her first and last car ride. Blackwell's old age was beginning to limit her activities.[1]

In 1907, while holidaying in Kilmun, Scotland, Blackwell fell down a flight of stairs, and was left almost completely mentally and physically disabled.[21] On 31 May 1910, she died at her home in Hastings, Sussex, after suffering a stroke that paralyzed half her body. Her ashes were buried in the graveyard of St Munn's Parish Church, Kilmun, and obituaries honouring her appeared in publications such as The Lancet[22] and The British Medical Journal.[23]

The British artist Edith Holden, whose Unitarian family were Blackwell's relatives, was given the middle name "Blackwell" in her honor.

Works

- 1849 The Causes and Treatment of Typhus, or Shipfever (thesis)

- 1852 The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls (brochure, compilation of lecture series) pub. by George Putnam

- 1856 An appeal in behalf of the medical education of women[24]

- 1860 Medicine as a Profession for Women (lecture published by the trustees of the New York Infirmary for Women)

- 1864 Address on the Medical Education of Women[25]

- 1878 Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of their Children in Relation to Sex (eight editions, republished as The Moral Education of the Young in Relation to Sex)

- 1881 "Medicine and Morality" (published in Modern Review)

- 1887 Purchase of Women: the Great Economic Blunder

- 1871 The Religion of Health (compilation of lecture series, three editions)

- 1883 Wrong and Right Methods of Dealing with Social Evil, as shown by English Parliamentary Evidence[26]

- 1888 On the Decay of Municipal Representative Government – A Chapter of Personal Experience (Moral Reform League)

- 1890 The Influence of Women in the Profession of Medicine[27]

- 1891 Erroneous Method in Medical Education etc. (Women's Printing Society)

- 1892 Why Hygienic Congresses Fail

- 1895 Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women – Autobiographical Sketches (Longmans, reprinted New York: Schocken Books, 1977)

- 1898 Scientific Method in Biology

- 1902 Essays in Medical Sociology, 2 vols (Ernest Bell)

Honours

Two institutions honour Elizabeth Blackwell as an alumna:

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges, the current name of Geneva College, the founding institution of Geneva Medical College

- State University of New York (SUNY) at Syracuse, which acquired Geneva Medical College in 1950 and renamed it "State University of New York Upstate Medical University" in 1999.

Since 1949, the American Medical Women's Association has awarded the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal annually to a woman physician.[28] Hobart and William Smith Colleges awards an annual Elizabeth Blackwell Award to women who have demonstrated "outstanding service to humankind."[29]

The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Elizabeth Blackwell.[30]

In 2013 the University of Bristol launched the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research.

See also

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, first woman to gain a medical qualification in Britain

- James Barry, possibly the first female bodied doctor (assigned female at birth but living as a man)

- List of first female physicians by country

Further reading

- Baker, Rachel (1944). The first woman doctor: the story of Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D. J. Messner, Inc., New York, OCLC 848388

- "Changing the Face of Medicine | Dr. Emily Blackwell". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Mesnard, E.M. (1889). Miss Elizabeth Blackwell and the Women of Medicine. Paris.

- Morantz, Regina. "Feminism, Professionalism and Germs: The Thought of Mary Putnam Jacobi and Elizabeth Blackwell," American Quarterly (1982) 34:461–478. in JSTOR

- Morantz-Sanchez, Regina. "Feminist theory and historical practice: Rereading Elizabeth Blackwell," History & Theory (1992) 31#4 pp 51–69 in JSTOR

- Ross, Ishbel (1944). Child of Destiny. New York: Harper.

- Wilson, Dorothy Clarke (1970). Lone woman: the story of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor. Little Brown, Boston, OCLC 56257

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Sahli, Nancy Ann (1982). Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D., (1871–1910): a biography. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-14106-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Blackwell, Elizabeth, and Millicent Garrett Fawcett. Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1914. Print.

- ^ Kline, Nancy (1997). Elizabeth Blackwell: First Woman M.D. Conari Press. p. 1772. ISBN 9781609254780.

- ^ Elizabeth Blackwell, Diary, 19–21 December 1838 (Blackwell Family Papers, Library of Congress).

- ^ a b Blackwell, Elizabeth (1895). Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women: Autobiographical Sketches. London and New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ a b Curtis, Robert H. (1993). Great Lives: Medicine. New York, New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

- ^ Smith, Stephen. Letter. The Medical Co-education of the Sexes. New York Church Union. 1892.

- ^ "Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell's Graduation: An Eye-Witness Account by Margaret Munro De Lancey"

- ^ a b c d Elizabeth Blackwell. Letters to Barbara Bodichon. 29 Jan 1859. 25 Nov 1860. 5 June 1861 (Elizabeth Blackwell Collection, Special Collections, Columbia University Library).

- ^ Moberly Bell, Enid (1953). Storming the Citadel: The Rise of the Woman Doctor. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. p. 25.

- ^ Elizabeth Blackwell. Letter to Samuel C. Blackwell. 21 Sep 1874. (Blackwell Family Papers, Library of Congress).

- ^ Regina Morantz, "Feminism, Professionalism and Germs: The Thought of Mary Putnam Jacobi and Elizabeth Blackwell," American Quarterly (1982) 34:461–478. in JSTOR

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth (1892). Why Hygienic Congresses Fail. London: G. Bell.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth (1888). A Medical Address on the Benevolence of Malthus, Contrasted with the Corruptions of Neo-Malthusianism. London: T. W. Danks & Co.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth (1890). Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of their Children. New York: Brentano's Literary Emporium.

- ^ Kitty Barry Blackwell. Letter to Alice Stone Blackwell. 24 Mar 1877. (Blackwell Family Papers, Library of Congress)

- ^ Elizabeth Blackwell. Letter to Emily Blackwell. 23 Jan 1855. (Blackwell Family Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College)

- ^ Elizabeth Blackwell. Letter to Emily Blackwell. 1 Oct 1856. (Blackwell Family Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College)

- ^ Blackwell, Alice Stone. Tribute to Kttty Barry. Vineyard Gazette. 19 June 1936. (Blackwell Family Papers, Library of Congress)

- ^ Kitty Barry Blackwell. Letter to Alice Stone Blackwell. 24 March 1877. (Blackwell Family Papers, Library of Congress).

- ^ Argyll Mausoleum, Elizabeth Blackwell

- ^ "Obituary". Lancet. 175 (4528): 1657–1658. 1910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)51682-1.

- ^ "Obituary, Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D.". BMJ. 1: 1523–1524. 1910. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2581.1523-b.

- ^ Collins, Stacy B.; Haydock, Robert; Blackwell, Elizabeth; Blackwell, Emily; Zakrzewska, Maria E. An appeal in behalf of the medical education of women. New York: New York Infirmary for Women.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth; Blackwell, Emily (1864). Address on the Medical Education of Women. New York: Baptist & Taylor. LCCN e12000210. OCLC 609514383.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth (1883). Wrong and right methods of dealing with social evil, as shown by English parliamentary evidence. New York: A. Brentano. LCCN 76378843.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth (1890). The influence of women in the profession of medicine. Baltimore: Unknown.

- ^ "Elizabeth Blackwell Letters, circa 1850–1884". Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "The Blackwell Award". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

External links

- Works by Elizabeth Blackwell online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Elizabeth Blackwell Collection on New York Heritage Digital Collections

- Some places and memories related to Elizabeth Blackwell

- Women in Science

- An online history at the National Institutes of Health, including copies of historical documents

- An online biography of Elizabeth Blackwell, with links to more articles on Blackwell and others in her famous family, plus links to many resources on the Net

- Biography from the National Institute of Health

- Elizabeth Blackwell at the Hobart and William Smith Colleges Archives

- Elizabeth Blackwell Resources Available in Hobart and William Smith Colleges Archives

- Chronological Bibliography of Selected Scholarly Works by Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

- Elizabeth Blackwell at winningthevote.org

- Elizabeth Blackwell at Find a Grave

- Papers, 1835–1960. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Works by or about Elizabeth Blackwell at Wikisource

Works by or about Elizabeth Blackwell at Wikisource Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Blackwell, Elizabeth". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Smith, Charlotte Fell (1912). "Blackwell, Elizabeth". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 1. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Blackwell, Elizabeth". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Blackwell, Elizabeth". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Thompson Cooper (1884) "Blackwell, Elizabeth," Men of the Time (eleventh edition).

- Use dmy dates from May 2012

- 1821 births

- 1910 deaths

- 19th-century American physicians

- American abolitionists

- American classical liberals

- American feminists

- American physicians

- American women physicians

- American women's rights activists

- Anti-contraception activists

- Blackwell family

- British classical liberals

- English emigrants to the United States

- Geneva Medical College alumni

- People from Bristol

- People from Cincinnati

- People from Hastings

- People from New York City

- Sex educators

- Women in the American Civil War

- Women of the Victorian era