House of Orange-Nassau

| House of Orange-Nassau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parent house | House of Nassau |

| Country | Netherlands, England, Scotland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Orange, Nassau |

| Founded | 1544 |

| Founder | William I of Orange (William the Silent) |

| Current head | Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands |

| Titles | |

| Estate(s) | Netherlands |

| Dissolution | Since 1962 extinct in the original agnatic line |

The House of Orange-Nassau (in Dutch: Huis van Oranje-Nassau, pronounced [ˈɦœy̯s fɑn oːˈrɑɲə ˈnɑsʌu̯]), a branch of the European House of Nassau, has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherlands — and at times in Europe — especially since William I of Orange (also known as "William the Silent" and "Father of the Fatherland") organized the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule, which after the Eighty Years' War led to an independent Dutch state.

Several members of the house served during this war and after as governor or stadtholder (Dutch stadhouder) during the Dutch Republic. However, in 1815, after a long period as a republic, the Netherlands became a monarchy under the House of Orange-Nassau.

The dynasty was established as a result of the marriage of Henry III of Nassau-Breda from Germany and Claudia of Châlon-Orange from French Burgundy in 1515. Their son René inherited in 1530 the independent and sovereign Principality of Orange from his mother's brother, Philibert of Châlon. As the first Nassau to be the Prince of Orange, René could have used "Orange-Nassau" as his new family name. However, his uncle, in his will, had stipulated that René should continue the use of the name Châlon-Orange. History knows him therefore as René of Châlon. After the death of René in 1544 his cousin William of Nassau-Dillenburg inherited all his lands. This "William I of Orange", in English better known as William the Silent, became the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau.[1]: 10

The House of Nassau

The Castle of Nassau was founded around 1100 by Count Dudo-Henry of Laurenburg (German: Dudo-Heinrich von Laurenburg), the founder of the House of Nassau. In 1120, Dudo-Henry's sons and successors, Counts Robert I (German: Ruprecht; also translated Rupert) and Arnold I of Laurenburg, established themselves at Nassau Castle with its tower. They renovated and extended the castle complex in 1124 (see Nassau Castle).

The first man to be called the count of Nassau was Robert I of Nassau (Ruprecht in German), who lived in the first half of the 13th century (see family tree below). The Nassau family married into the family of the neighboring Counts of Arnstein (now Kloster Arnstein). His sons Walram and Otto split the Nassau possessions. The descendants of Walram became known as the Walram Line, which became Dukes of Nassau, and in 1890, the Grand Dukes of Luxembourg. This line also included Adolph of Nassau, who was elected King of the Romans in 1292. The descendants of Otto became known as the Ottonian Line, which inherited parts of Nassau County, and properties in France and the Netherlands.

The House of Orange-Nassau stems from the younger Ottonian Line. The first of this line to establish himself in the Netherlands was John I, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, who married Margareta of the Marck. The real founder of the Nassau fortunes in the Netherlands was John's son, Engelbert I. He became counsellor to the Burgundian Dukes of Brabant, first to Anton of Burgundy, and later to his son Jan IV of Brabant. He also would later serve Philip the Good. In 1403 he married the Dutch noblewoman Johanna van Polanen, and so inherited lands in the Netherlands, with the Barony of Breda as the core of the Dutch possessions and the family fortune.[2]: 35

A noble's power was often based on his ownership of vast tracts of land and lucrative offices. It also helped that much of the lands that the House of Orange and Nassau controlled sat under one of the commercial and mercantile centers of the world (see below under Lands and Titles. The importance of the Nassaus grew throughout the 15th and 16th centuries as they became councilors, generals and stadholders of the Habsburgs (see armorial of the great nobles of the Burgundian Netherlands and List of Knights of the Golden Fleece). Engelbert II of Nassau served Charles the Bold and Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, who had married Charles's daughter Mary of Burgundy. In 1496 he was appointed stadtholder of Flanders and by 1498 he had been named President of the Grand Conseil. In 1501, Maximilian named him Lieutenant-General of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. From that point forward (until his death in 1504), Engelbert was the principal representative of the Habsburg Empire to the region. Hendrik III of Nassau-Breda was appointed stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland by Charles of Ghent in the beginning of the 16th century. Hendrik was succeeded by his son René of Châlon-Orange in 1538, who was, as his full name stated, the Prince of Orange. When René died prematurely on the battlefield in 1544 his possessions passed to his cousin, William I of Orange. From then on, the family members called themselves "Orange-Nassau."[1]: 8 [2]: 37 [3]: vol3, pp3-4 [4]: 37, 107, 139 See also Adolf of Germany.

The Dutch rebellion

Although Charles V resisted the Protestant Reformation, he ruled the Dutch territories wisely with moderation and regard for local customs, and he did not persecute his Protestant subjects on a large scale. His son Philip II inherited his antipathy for the Protestants but not his moderation. Under the reign of Philip, a true persecution of Protestants was initiated and taxes were raised to an outrageous level. Discontent arose and William of Orange (with his vague Lutheran childhood) stood up for the Protestant (mainly Calvinist) inhabitants of the Netherlands. Things went badly after the Eighty Years' War started in 1568, but luck turned to his advantage when Protestant rebels attacking from the North Sea captured Brielle, a coastal town in present-day South Holland in 1572. Many cities in Holland began to support William. During the 1570s he had to defend his core territories in Holland several times, but in the 1580s the inland cities in Holland were secure. William of Orange was considered a threat to Spanish rule in the area and was assassinated in 1584 by a hired killer sent by Philip.[3]: vol3, p177 [4]: 216 [6]

William was succeeded by his second son Maurits, a Protestant who proved an excellent military commander. His abilities as a commander and the lack of strong leadership in Spain after the death of Philip II (1598) gave Maurits excellent opportunities to conquer large parts of the present-day Dutch territory.[3]: vol 3, pp243-253 [7] In 1585 Maurits was elected stadtholder of the Provinces of Holland and Zealand as his father's successor and as a counterpose to Elizabeth's delegate, the Earl of Leicester. In 1587 he was appointed captain-general (military commander-in-chief) of the armies of the Dutch Republic. In the early years of the 17th century there arose quarrels between stadtholder and oligarchist regents—a group of powerful merchants led by Johan van Oldebarnevelt—because Maurits wanted more powers in the Republic. Maurits won this power struggle by arranging the judicial murder of Oldebarnevelt.[4]: 421–432, 459 [7]

Expansion of dynastic power

Maurits died unmarried in 1625 and left no legitimate children. He was succeeded by his half-brother Frederick Henry (Dutch: Frederik Hendrik), youngest son of William I. Maurits urged his successor on his deathbed to marry as soon as possible. A few weeks after Maurits's death, he married Amalia van Solms-Braunfels. Frederick Henry and Amalia were the parents of a son and several daughters. These daughters were married to important noble houses such as the house of Hohenzollern, but also to the Frisian Nassaus, who were stadtholders in Friesland. His only son, William, married Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, the eldest daughter of Charles I of Scotland and England. These dynastic moves were the work of Amalia.[1]: 72–74 [8]: 61

Exile and resurgence

Frederick Henry died in 1647 and his son succeeded him. As the Treaty of Munster was about to be signed, thereby ending the Eighty Years' War, William tried to maintain the powers he had in wartime as military commander. These would necessarily be diminished in peacetime as the army would be reduced, along with his income. This met with great opposition from the regents. When Andries Bicker and Cornelis de Graeff, the great regents of the city of Amsterdam refused some mayors he appointed, he besieged Amsterdam. The siege provoked the wrath of the regents. William died of smallpox on November 6, 1650, leaving only a posthumous son, William III (*November 14, 1650). Since the Prince of Orange upon the death of William II, William III, was an infant, the regents used this opportunity to leave the stadtholdership vacant. This inaugurated the era in Dutch history that is known as the First Stadtholderless Period.[9] A quarrel about the education of the young prince arose between his mother and his grandmother Amalia (who outlived her husband by 28 years). Amalia wanted an education which was pointed at the resurgence of the House of Orange to power, but Mary wanted a pure English education. The Estates of Holland, under Jan de Witt and Cornelis de Graeff, meddled in the education and made William a "child of state" to be educated by the state. The doctrine used in this education was keeping William from the throne. William became indeed very docile to the wishes of the regents and the Estates.[8][9]

The Dutch Republic was attacked by France and England in 1672. The military function of stadtholder was no longer superfluous, and with the support of the Orangists, William was restored, and he became the stadtholder. William successfully repelled the invasion and seized royal power. He became more powerful than his predecessors from the Eighty Years' War.[8][9] In 1677, William married his cousin Mary Stuart, the daughter of the future king James II of England. In 1688, William embarked on a mission to depose his Catholic father-in-law from the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. He and his wife were crowned the King and Queen of England on April 11, 1689. With the accession to the thrones of the three kingdoms, he became one of the most powerful sovereigns in Europe, and the only one to defeat Louis XIV of France.[8] William III died childless after a riding accident on March 8, 1702, leaving the main male line of the House of Orange extinct, and leaving Scotland, England and Ireland to his sister-in-law Queen Anne.

The second stadtholderless era

The regents found that they had suffered under the powerful leadership of King William III and left the stadtholderate vacant for the second time. As William III died childless in 1702 the principality became a matter of dispute between Prince John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz of the Frisian Nassaus and King Frederick I of Prussia, who both claimed the title Prince of Orange. Both descended from Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange. The King of Prussia was his grandson through his mother, Countess Luise Henriette of Nassau. Frederick Henry in his will had appointed this line as successor in the case the main House of Orange-Nassau would die out. John William Friso was a great-grandson of Frederick Henry (through Countess Albertine Agnes of Nassau, another daughter) and was appointed heir in William III's will. The principality was captured by the forces of King Louis XIV of France under François Adhémar de Monteil, Count of Grignan, in the Franco-Dutch War in 1672, and again in August 1682. With the Treaty of Utrecht that ended the wars of Louis XIV, the territory was formally ceded to France by Frederick I in 1713.[2]: 1 John William Friso drowned in 1711 in the Hollands Diep near Moerdijk, and he left his posthumously born son William IV, Prince of Orange. That son succeeded at that time his father as stadtholder in Friesland (as the stadtholderate had been hereditary in that province since 1664), and Groningen. William IV was proclaimed the stadtholder of Guelders, Overijssel, and Utrecht in 1722. When the French invaded Holland in 1747, William IV was appointed stadtholder in Holland and Zeeland also. The stadtholderate was made hereditary in both the male and the female lines in all provinces at the same time.[1] : 148–151, 170

The end of the stadtholderate

William IV died in 1751, leaving his three-year-old son, William V, as the stadtholder. Since William V was still a minor, the regents reigned for him. He would grow out to be an indecisive person, a character defect which would come to haunt William V his whole life. His marriage to Wilhelmina of Prussia relieved this defect to some degree. In 1787, Willem V survived an attempt to dispose him by the Patriots (democratic revolutionaries) after the Kingdom of Prussia intervened. When the French invaded Holland in 1795, William V was forced into exile, and he was never to return alive to Holland.[1]: 228–229 [3]: vol5, 289

After 1795, the House of Orange-Nassau faced a difficult period, surviving in exile at other European courts, especially those of Prussia and England. Following the recognition of the Batavian Republic by the 1801 Oranienstein Letters, William V's son William VI renounced the stadtholdership in 1802. In return, he received a few territories from First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte of the French Republic (Treaty of Amiens), which was established as the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda.[10] William V died in 1806.

| Dutch royalty House of Orange-Nassau |

|---|

|

| King William I |

| King William II |

| King William III |

| Queen Wilhelmina |

| Queen Juliana |

| Queen Beatrix |

| King Willem-Alexander |

The Monarchy (since 1815)

A new spirit: the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

After a repressed Dutch rebel action, Prussian and Cossack troops drove out the French in 1813, with the support of the Patriots of 1785. A provisional government was formed, most of whose members had helped drive out William V 18 years earlier. However, they were realistic enough to realize that any new government would have to be headed by William V's son, William Frederick (William VI). All agreed that it would be better in the long term for the Dutch to restore William themselves rather than have him imposed by the allies.[1]: 230

At the invitation of the provisional government, William Frederick returned to the Netherlands on November 30. This move was strongly supported by the United Kingdom, which sought ways to strengthen the Netherlands and deny future French aggressors easy access to the Low Countries' Channel ports. The provisional government offered William the crown. He refused, believing that a stadholdership would give him more power. Thus, on December 6, William proclaimed himself hereditary sovereign prince of the Netherlands—something between a kingship and a stadholdership. In 1814, he was awarded sovereignty over the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège as well. On March 15, 1815 with the support of the powers gathered at the Congress of Vienna, William proclaimed himself King William I. He was also made grand duke of Luxembourg, and the title 'Prince of Orange' was changed to 'Prince of Oranje'. The two countries remained separate despite sharing a common monarch. William had thus fulfilled the House of Orange's three-century quest to unite the Low Countries.[3]: vol5, 398

As king of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, William tried to establish one common culture. This provoked resistance in the southern parts of the country, which had been culturally separate from the north since 1581. He was considered an enlightened despot.[3]: vol5, 399

The Prince of Orange held rights to Nassau lands (Dillenburg, Dietz, Beilstein, Hadamar, Siegen) in central Germany. On the other hand, the King of Prussia, Frederick William III—brother-in-law and first cousin of William I, had beginning from 1813 managed to establish his rule in Luxembourg, which he regarded as his inheritance from Anne, Duchess of Luxembourg who had died over three centuries earlier. At the Congress of Vienna, the two brothers-in-law agreed to a trade—Frederick William received William I's ancestral lands while William I received Luxembourg. Both got what was geographically nearer to their center of power.[3]: vol5, 392

In 1830, most of the southern portion of William's realm—the former Austrian Netherlands and Prince-Bishopric—declared independence as Belgium. William fought a disastrous war until 1839 when he was forced to settle for peace. With his realm halved, he decided to abdicate in 1840 in favour of his son, William II. Although William II shared his father's conservative inclinations, in 1848 he accepted an amended constitution that significantly curbed his own authority and transferred the real power to the States General. He took this step to prevent the Revolution of 1848 from spreading to his country.[3]: vol5, 455–463

William III and the threat of extinction

William II died in 1849. He was succeeded by his son, William III. A rather conservative, even reactionary man, William III was sharply opposed to the new 1848 constitution. He continually tried to form governments that were dependent on his support, even though it was prohibitively difficult for a government to stay in office against the will of Parliament. In 1868, he tried to sell Luxembourg to France, which was the source of a quarrel between Prussia and France.[3]: vol5, 483

William III had a rather unhappy marriage with Sophie of Württemberg, and his heirs died young. This raised the possibility of the extinction of the House of Orange-Nassau. After the death of Queen Sophie in 1877, William remarried, to Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont in 1879. One year later, Queen Emma gave birth to their daughter and the royal heiress, Wilhelmina.[3]: vol5, 497–498

A modern monarchy

Wilhelmina was queen of the Netherlands for 58 years, from 1890 to 1948. Because she was only 10 years old in 1890, her mother, Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont, was the regent until Wilhelmina's 18th birthday in 1898. Since females were not allowed to hold power in Luxembourg, due to Salic law, Luxembourg passed to the House of Nassau-Weilburg, a collateral line to the House of Orange-Nassau. For a time, it appeared that the Dutch royal family would die with Wilhelmina. Her half-brother, Prince Alexander, had died in 1884, and no royal babies were born from then until Wilhemina gave birth to her only child, Juliana, in 1909. The Dutch royal house remained quite small until the latter 1930s and the early 1940s, during which Juliana gave birth to four daughters. Although the House of Orange died out in its male line with the death of Queen Wilhelmina, the name "Orange" continues to be used by the Dutch royalty [3]: vol5, 507–508 and as evidenced in many patriotic songs, such as "Oranje boven".

The Netherlands remained neutral in World War I, during her reign, and the country was not invaded by Germany, as neighboring Belgium was.[11]

Nevertheless, Queen Wilhelmina became a symbol of the Dutch resistance during World War II. The moral authority of the Monarchy was restored because of her rule. After 58 years on the throne as the Queen, Wilhelmina decided to abdicate in favour of her daughter, Juliana. Juliana had the reputation of making the monarchy less "aloof", and under her reign the Monarchy became known as the "cycling monarchy". Members of the royal family were often seen bicycling through the cities and the countryside under Juliana.[11]

A royal marriage policy quarrel occurred starting in 1966 when Juliana's eldest daughter, the future Queen Beatrix, decided to marry Claus von Amsberg, a German diplomat. The marriage of a member of the royal family to a German was quite controversial in the Netherlands, which had suffered under Nazi German occupation in 1940–45. This reluctance to accept a German consort probably was exacerbated by von Amsberg's former membership in the Hitler Youth under the Nazi regime in his native country, and also his following service in the German Wehrmacht. Beatrix needed permission from the government to marry anyone if she wanted to remain heiress to the throne, but after some argument, it was granted. As the years went by, Prince Claus was fully accepted by the Dutch people. In time, he became one of the most popular members of the Dutch monarchy, and his death in 2002 was widely mourned.[11]

On April 30, 1980, Queen Juliana abdicated in favor of her daughter, Beatrix. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the Dutch monarchy remained popular with a large part of the population. Beatrix's eldest son, Willem-Alexander, was born on April 27, 1967; the first immediate male heir to the Dutch throne since the death of his great-grandfather, Prince Alexander, in 1884. Willem-Alexander married Máxima Zorreguieta, an Argentine banker, in 2002; the first commoner to ever marry an heir apparent to the Dutch throne. They are parents of three daughters: Catharina-Amalia, Alexia, and Ariane. After a long struggle with neurological illness, Queen Juliana died on March 20, 2004, and her husband, Prince Bernhard, died on December 1 of that same year.[11]

Upon Beatrix's abdication on April 30, 2013, the Prince of Orange was inaugurated as King Willem-Alexander, becoming the Netherlands' first male ruler since 1890. His eldest daughter, Catharina-Amalia, as heiress apparent to the throne, became Princess of Orange in her own right.[11]

Net worth

Unlike other royal houses, there has always been a separation in the Netherlands between what was owned by the state and used by the House of Orange in their offices as monarch, or previously, stadtholder, and the personal investments and fortune of the House of Orange.[citation needed]

The Royal Family's biggest wealth advantage, is that they don't need to live off their wealth for their day-to-day needs and job functions. As monarch, the King or Queen has use of, but not ownership of, the Huis ten Bosch as a residence and Noordeinde Palace as a work palace. In addition the Royal Palace of Amsterdam is also at the disposal of the monarch (although it is only used for state visits and is open to the public when not in use for that purpose), as is Soestdijk Palace (which is open to the public and not in official use at all at this time).[12] The crown jewels, comprising the crown, orb and sceptre, Sword of State, royal banner, and ermine mantle have been placed in the Crown Property Trust. The trust also holds the items used on ceremonial occasions, such as the carriages, table silver, and dinner services. Placing these goods in the hands of a trust ensures that they will remain at the disposal of the monarch in perpetuity.[13] Members of the Royal House also receive stipends in order to carry out their duties which are listed here. The Royal House is also exempt from income, inheritance, and personal tax.[14][citation needed]

The House of Orange has long had the reputation of being one of the wealthier royal houses in the world, largely due to their business investments. They are rumored to have a large stake in Royal Dutch Shell. Other significant shares are supposed to be in the Philips Electronics company (known in the Netherlands as Royal Philips), KLM-Royal Dutch Airlines, and the Holland-America Line ( cruise ships)- How significant is a matter of conjecture, as their private finances, unlike their public stipends as monarch, are not open to scrutiny. The holdings are spread among real estate (include Castle Drakensteyn in Holland and a villa in Tuscany), investments, and commercial companies.[15] It should be noted that given Royal Dutch Shell's 2012 earnings, revenue, and equity, even a few percent stake in this company alone would exceed the estimates of earnings below.

Forbes magazine is the most consistent [citation needed] in estimating the net worth of heads of state. As late as 2001, the fortune of the Royal Family was estimated by various sources (Forbes magazine) at $3.2 billion. Most of the wealth was reported to come from the family's longstanding stake in the Royal Dutch/Shell Group. At one time, the Oranges reportedly owned as much as 25% of the oil company; their stake is in 2001 was estimated at a minimum of 2%, worth $2.7 billion on the May 21 cutoff date for the Billionaires issue. The family also was estimated to have a 1% stake in financial services firm ABN-AMRO.[16][17]

The fortune seems to have been hit by declines in real estate and equities after 2008. They were also rumored to have lost up to $100 million when Bernard Madoff's Ponzi scheme collapsed, though the royal house denies the allegations.[18] In 2009, Forbes estimated her wealth at US$300 million.[19] This could also have been due to splitting the fortune between Queen Beatrix and her 3 sisters, as there is no right of the eldest to inherit the whole property. A surge in export revenue, recovery in real estate and strong stock market have helped steady royal family’s fortunes, but uncertainty over the new government and future austerity measures needed to bring budget deficits in line may dampen future prospects. In July 2010, Forbes magazine estimated her net worth at $200 million [15][20] This estimate was repeated in April 2011.[21]

Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

William I

| 24 April 1533 – 10 July 1584 (aged 51) | 1559 | 1584 | Stadtholder[22] | Orange-Nassau |  |

Maurice

| 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625 (aged 57) | 1585 | 1625 | Stadtholder,[23] son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

Frederick Henry

| 29 January 1584 – 14 March 1647 (aged 63) | 1625 | 1647 | Stadtholder,[24] son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

William II

| 27 May 1626 – 6 November 1650 (aged 24) | 14 March 1647 | 6 November 1650 | Stadtholder,[25] son of Frederick Henry | Orange-Nassau |  |

William III

| 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702 (aged 51) | 4 July 1672 | 8 March 1702 | Stadtholder,[26] son of William II[27] | Orange-Nassau |  |

William IV

| 1 September 1711 – 22 October 1751 (aged 40) | 1 September 1711 (under the regency of Marie Louise until 1731) | 22 October 1751 | Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands,[28] son of John William Friso | Orange-Nassau |  |

William V

| 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806 (aged 58) | 22 October 1751 | 9 April 1806 | Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands, son of William IV, succeeded by his son King William I (-> Principality of the Netherlands (1813 - 1815) | Orange-Nassau |  |

Stadtholderate under the House of Nassau[29]

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

John VI

| 22 November 1536 – 8 October 1606 (aged 69) | 1578 | 1581 | Stadtholder,[30] brother of William I | Nassau |  |

William Louis

| 13 March 1560 – 31 May 1620 (aged 60) | 1584 | 1620 | Stadtholder,[31] son of John VI | Nassau |  |

| Ernest Casimir I | 22 December 1573 – 2 June 1632 (aged 58) | 1620 | 1632 | Stadtholder,[32] son of John VI | Nassau |  |

| Henry Casimir I | 21 January 1612 – 13 July 1640 (aged 28) | 1632 | 1640 | Stadtholder,[33] son of Ernest Casimir I | Nassau |  |

| William Frederick | 7 August 1613 – 31 October 1664 (aged 51) | 1640 | 1664 | Stadtholder,[34] son of Ernest Casimir I | Nassau |  |

| Henry Casimir II | 18 January 1657 – 25 March 1696 (aged 39) | 18 January 1664 | 25 March 1696 | Hereditary Stadtholder,[35] son of William Frederick | Nassau |  |

| John William Friso | 4 August 1687 – 14 July 1711 (aged 23) | 25 March 1696 | 14 July 1711 | Hereditary Stadtholder,[36] son of Henry Casimir II, succeeded by his son William IV of Orange-Nassau, Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Netherlands (-> Stadtholderate under the House of Orange-Nassau | Nassau, Orange-Nassau |  |

Principality of the Netherlands (1813-1815)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 6 December 1813 | 16 March 1815 | Raised Netherlands to status of kingdom in 1815, son of Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–present)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William I | 24 August 1772 – 12 December 1843 (aged 71) | 16 March 1815 | 7 October 1840 | Son of the last Stadtholder William V | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William II | 6 December 1792 – 17 March 1849 (aged 56) | 7 October 1840 | 17 March 1849 | Son of William I | Orange-Nassau |  |

| William III | 17 February 1817 – 23 November 1890 (aged 73) | 17 March 1849 | 23 November 1890 | Son of William II | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Wilhelmina | 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962 (aged 82) | 23 November 1890 | 4 September 1948 | Daughter of William III | Orange-Nassau |  |

| Juliana | 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004 (aged 94) | 4 September 1948 | 30 April 1980 | Daughter of Wilhelmina | Orange-Nassau (House of Mecklenburg) |  |

| Beatrix | 31 January 1938 | 30 April 1980 | 30 April 2013 | Daughter of Juliana | Orange-Nassau (House of Lippe) |  |

| Willem-Alexander | 27 April 1967 | 30 April 2013 | Son of Beatrix | Orange-Nassau (House of Amsberg) |  |

The Royal Family and the Royal House

A distinction is made in the Netherlands between the royal family and the Royal House.

The royal family is the Orange-Nassau family.

However, not every member of the family is also a member of the Royal House. By Act of Parliament, the members of the Royal House are:[11]

- the monarch (King or Queen);

- the former monarch (on abdication);

- the members of the royal family in the line of succession to the throne, limited to the second degree of sanguinity reckoned from the reigning monarch;

- H.R.H Princess Margriet of the Netherlands, (for whom an exception was made);

- the spouses of the above.

Members of the Royal House lose their membership and designation as prince or princess of the Netherlands if they lose the membership of the Royal House on the succession of a new monarch (not being in the second degree of sanguinity to the monarch anymore), or marry without the consent of the Dutch Parliament. For example, this happened with Prince Friso in 2004, when he married Mabel Wisse Smit. This is written down in the law of membership of the Royal House, 2002.[37]

Family tree

The lineage of the House of Nassau can be traced back to the 10th century.

| House of Nassau | |

|---|---|

Armorial of the House of Nassau Azure billetty or, a lion rampant of the last armed and langued gules | |

| Country | Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, England, Scotland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Nassau, Orange |

| Founded | c. 1093 |

| Founder | Dudo of Laurenburg |

| Current head | Henri, Grand Duke of Luxembourg (in cognatic line) |

| Titles |

|

| Estate(s) | Nassau Castle |

| Dissolution | 1985 (in agnatic line) |

| Cadet branches | House of Nassau-Weilburg House of Orange-Nassau House of Nassau-Corroy |

The House of Nassau is a diversified aristocratic dynasty in Europe. It is named after the lordship associated with Nassau Castle, located in present-day Nassau, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. With the fall of the Hohenstaufen in the first half of the 13th century royal power within Franconia evaporated and the former stem duchy fragmented into separate independent states. Nassau emerged as one of those independent states as part of the Holy Roman Empire. The lords of Nassau were originally titled "Count of Nassau", subject only to the Emperor, and then elevated to the princely class as "Princely Counts". Early on they divided into two main branches: the elder (Walramian) branch, that gave rise to the German king Adolf, and the younger (Ottonian) branch, that gave rise to the Princes of Orange and the monarchs of the Netherlands.

At the end of the Holy Roman Empire and the Napoleonic Wars, the Walramian branch had inherited or acquired all the Nassau ancestral lands and proclaimed themselves, with the permission of the Congress of Vienna, the "Dukes of Nassau", forming the independent state of Nassau with its capital at Wiesbaden; this territory today mainly lies in the German Federal State of Hesse, and partially in the neighbouring State of Rhineland-Palatinate. The Duchy was annexed in 1866 after the Austrian-Prussian War as an ally of Austria by Prussia. It was subsequently incorporated into the newly created Prussian Province of Hesse-Nassau.

Today, the term Nassau is used in Germany as a name for a geographical, historical and cultural region, but no longer has any political meaning. All Dutch and Luxembourgish monarchs since 1815 have been senior members of the House of Nassau. However, in 1890 in the Netherlands and in 1912 in Luxembourg, the male lines of heirs to the two thrones became extinct, so that since then, they have descended in the female line from the House of Nassau.

According to German tradition, the family name is passed on only in the male line of succession. The House would therefore, from this German perspective, have been extinct since 1985.[38][39] However, both Dutch and Luxembourgish monarchial traditions, constitutional rules and legislation in that matter differ from the German tradition, and thus neither country considers the House extinct. The Grand Duke of Luxembourg uses "Duke of Nassau" as his secondary title and a title of pretense to the dignity of Chief of the House of Nassau (being the most senior member of the eldest branch of the House), but not to lay any territorial claims to the former Duchy of Nassau which is now part of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Origins

The area that came to be the county of Nassau was part of the Duchy of Franconia. When Franconia fragmented in the early 13th century with the fall of the Hohenstaufen, Nassau emerged as an independent state as part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Count Dudo-Henry of Laurenburg (c. 1060 – c. 1123) (German: Dudo von Laurenburg; Latin: Tuto de Lurinburg) is considered the founder of the House of Nassau.[40][41] Dudo was a son of Rupert (German: Ruprecht), the Archbishop of Mainz's Vogt in Siegerland.[42] Dudo was himself lord or Vogt of Lipporn and Miehlen and owned large parts of the lands of Lipporn/Laurenburg. There are more persons known who, as owners of the lands of Lipporn/Laurenburg (and thus the predecessors of Dudo), probably also were his ancestors. The first is a certain Drutwin mentioned in 881 as a landowner in Prüm, and who is the oldest known possible ancestor of the House of Nassau.[40]

Dudo is mentioned as Tuto de Lurinburg between 1093 and 1117. Dudo built the castle of Laurenburg on the Lahn a few kilometers upriver from Nassau around 1090 as the seat of his lordship.[43] He is first mentioned in a document in the purported founding-charter of Maria Laach Abbey in 1093 (although many historians consider the document to be fabricated). In 1159, Nassau Castle became the ruling seat, and the house is now named after this castle. In a charter dated 1134 (after his death) he is mentioned as Count of Laurenburg.[40]

In 1117, Dudo donated land to Schaffhausen Abbey for construction of a monastery in Lipporn. Around 1117, Dudo, Count of Laurenburg founded at Lipporn a Benedictine priory dedicated and named for Saint Florin of Koblenz, and dependent on the Benedictine All Saints Abbey in Schaffhausen. About 1126, his son, Rupert I, Count of Laurenburg, the Vogt of Lipporn, established it as a separate and independent abbey.[44] The Romanesque buildings were constructed between 1126 and 1145, presumably with a three-nave basilica. The abbey included both a monastery for monks and a small, separate one for nuns.[45]

In 1122, Dudo received the castle of Idstein in the Taunus as a fief under the Archbishopric of Mainz. This was part of the inheritance of Count Udalrich of Idstein-Eppstein. He also received the Vogtship of the richly endowed Benedictine Bleidenstadt Abbey (in present-day Taunusstein).[46]

The Counts of Laurenburg and Nassau expanded their authority under the brothers Robert (Ruprecht) I (1123–1154) and Arnold I of Laurenburg (1123–1148). Robert was the first person to call himself Count of Nassau, but the title was not confirmed until 1159, five years after Robert's death. Robert's son Walram I (1154–1198) was the first person to be legally titled Count of Nassau.

The chronology of the Counts of Laurenburg is not certain and the link between Robert I and Walram I is especially controversial. Also, some sources consider Gerhard, listed as co-Count of Laurenburg in 1148, to be the son of Robert I's brother, Arnold I.[47] However, Erich Brandenburg in his Die Nachkommen Karls des Großen states that it is most likely that Gerhard was Robert I's son, because Gerard was the name of Beatrix of Limburg's maternal grandfather.[48]

Geography

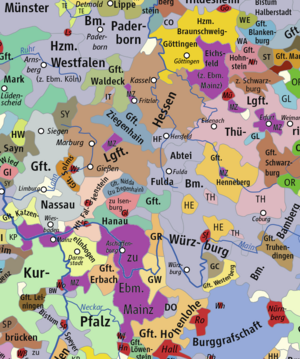

As noted above, the county of Nassau was part of the stem Duchy of Franconia. It branched off northeast from the Rhine River and followed the course of the Lahn and Sieg rivers. Northeast and southeast of it was the lands of the House of Hesse. With the fall of the Hohenstaufen in the first half of the 13th century royal power within Franconia evaporated and the former stem duchy fragmented into separate independent states. Nassau emerged as one of those independent states as part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Nassau, originally a county, but part of the duchy of Franconia, developed on the lower Lahn river in what is known today as Rhineland-Palatinate. The town of Nassau was founded in 915.[49] As noted above, Dudo of Laurenburg held Nassau as a fiefdom as granted by the Bishopric of Worms. His son, Rupert, built the Nassau Castle there around 1125, declaring himself "Count of Nassau". This title was not officially acknowledged by the Bishop of Worms until 1159 under the rule of Rupert's son, Walram. By 1159, the County of Nassau effectively claimed rights of taxation, toll collection, and justice, at which point it can be considered to become a state.[49]

The Nassauers held the territory between the Taunus and the Westerwald at the lower and middle Lahn. By 1128, they acquired the bailiwick of the Bishopric of Worms, which had numerous rights in the area, and thus created a link between their heritage at the lower Lahn and their possessions near Siegen. In the middle of the 12th century, this relationship was strengthened by the acquisition of parts of the Hesse-Thüringen feudal kingdom, namely the Herborner Mark, the Kalenberger Zent and the Court of Heimau (Löhnberg). Closely linked to this was the "Lordship of Westerwald", also in Nassau's possession at the time. At the end of the 12th century, the House acquired the Reichshof Wiesbaden, an important base in the southwest.

In 1255, after the Counts of Nassau acquired the estates of Weilburg, the sons of Count Henry II divided Nassau for the first time. Walram II received the county of Nassau-Weilburg. From 1328 on, his younger brother, Otto I, held the estates north of the Lahn river, namely the County of Nassau-Siegen and Nassau-Dillenburg. The boundary line was essentially the Lahn, with Otto receiving the northern part of the county with the cities of Siegen, Dillenburg, Herborn and Haiger and Walram retaining the section south of the river, including the cities of Weilburg and Idstein.

List of rulers

Counts of Laurenburg (ca. 1093–1159) and Nassau (1159–1255)

In 1255, Henry II's sons, Walram II and Otto I, split the Nassau possessions. The descendants of Walram became known as the Walram Line, which became important in the Countship of Nassau and Luxembourg. The descendants of Otto became known as the Ottonian Line, which would inherit parts of Nassau, France and the Netherlands. Both lines would often themselves be divided over the next few centuries. In 1783, the heads of various branches of the House of Nassau sealed the Nassau Family Pact (Erbverein) to regulate future succession in their states, and to establish a dynastic hierarchy whereby the Prince of Orange-Nassau-Dietz was recognised as President of the House of Nassau.[50]

The Walramian Line (1255–1985)

The Walramian Line concentrated their efforts primarily on their German lands. The exception was Adolf, King of the Romans (c. 1255 – 2 July 1298) who was the count of Nassau from about 1276 and the elected king of Germany from 1292 until his deposition by the prince-electors in 1298. He was never crowned by the pope, which would have secured him the imperial title. He was the first physically and mentally healthy ruler of the Holy Roman Empire ever to be deposed without a papal excommunication. Adolf died shortly afterwards in the Battle of Göllheim fighting against his successor Albert of Habsburg. He was the second in the succession of so-called count-kings of several rivalling comital houses striving after the Roman-German royal dignity after the expiration the Hohenstaufen. The Nassaus, however, were not on the imperial throne long enough to establish themselves in larger landholdings to increase their hereditary power such as the Luxemburgers did in Bohemia or the Habsburgs did in Austria.

After Gerlach's death, the possessions of the Walram line were divided into Nassau-Weilburg and Nassau-Wiesbaden-Idstein.

Nassau-Weilburg (1344–1816)

Count Walram II began the Countship of Nassau in Weilburg (Nassau-Weilburg), which existed to 1816. The Walram line also received the lordship of Merenberg in 1328 and Saarbrücken (by marriage) in 1353. The sovereigns of this house afterwards ruled the Duchy of Nassau from its establishment in 1806 as part of the Confederation of the Rhine (jointly with Nassau-Usingen until 1816). The last reigning Duke, Adolph, became Duke of Nassau in August 1839, following the death of his father William. The Duchy was annexed to Prussia in 1866 after Austria's defeat in the Austro-Prussian War.

From 1815 to 1839, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg was ruled by the kings of the Netherlands as a province of the Netherlands. Following the Treaty of London (1839), the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg became independent but remained in personal union with the Netherlands. Following the death of his sons, the Dutch king William III had no male heirs to succeed him. In the Netherlands, females were allowed to succeed to the throne. Luxembourg, however, followed Salic law which barred females from succession. Thus, upon King William III's death, the crown of the Netherlands passed to his only daughter, Wilhelmina, while that of Luxembourg passed to Adolph in accordance with the Nassau Family Pact. Adolph died in 1905 and was succeeded by his son, William IV.

and from 1890 the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The branch of Nassau-Weilburg ultimately became rulers of Luxembourg.

-

Weilburg Castle

-

East wing of the castle

Counts of Nassau-Weilburg (1344–1688), Princely counts of Nassau-Weilburg (1688–1816) and Dukes of Nassau (1816–1866)

Grand Dukes of Luxembourg (from the House of Nassau-Weilburg) – 1890–1912 and succession through a female onwards

- 1890–1905: Adolphe

- 1905–1912: William IV

- 1912–1919: Marie-Adélaïde

- 1919–1964: Charlotte

- 1964–2000: Jean

- 2000–present: Henri

-

Berg Castle, Luxembourg

Counts of Merenberg

Count of Merenberg (German: Graf von Merenberg) is a hereditary title of nobility that was bestowed in 1868 by the reigning Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, George Victor, upon the morganatic wife and male-line descendants of Prince Nikolaus Wilhelm of Nassau (1832–1905), younger brother of Adolf, last Duke of Nassau/Grand Duke of Luxembourg. Nicholas married Natalia Alexandrovna Pushkina (1836–1913), former wife of Russian general Mikhail Leontievich von Dubelt.

In 1907 Grand Duke Adolph declared the family non-dynastic/morganatic. Had they not been excluded from the succession, they would have inherited the headship of the house in 1912. Georg Nickolaus would have thus become the reigning Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

In 1907, William IV, obtained passage of a law in Luxembourg confirming the exclusion of the Merenbergs from succession to the grand ducal throne. Georg Nikolaus's protests against the Luxembourg Diet's confirmation of the succession rights of William IV's daughter, Princess Marie-Adélaïde, were expected to be taken up by the Netherlands and by the Great Powers which had guaranteed Luxembourg's neutrality in 1867.[52] Nonetheless, Marie-Adélaïde did succeed her father, to become Luxembourg's first female monarch, in 1912. She, in turn, abdicated in favour of her sister Charlotte, whose descendants have reigned over Luxembourg since then. Georg Nikolaus died in 1948. His son Georg Michael Alexander was the last legitimate descendant of the House of Nassau. He died in 1965

Counts of Nassau-Wiesbaden-Idstein (1344–1728)

From the documentary mention in 1102 until 1721, Idstein was, with interruptions, residence of the Counts of Nassau-Idstein and other Nassau lines. One of the Counts was, as said above, Adolf of Germany, the Holy Roman Emperor from 1292 to 1298.

The Nassau Counts' holdings were subdivided many times among heirs, with the parts being brought together again whenever a line died out. This yielded an older Nassau-Idstein line from 1480 to 1509, later merging once again with Nassau-Wiesbaden and Nassau-Weilburg and, from 1629 to 1721, a newer Nassau-Idstein line.

In 1721, Idstein passed to Nassau-Ottweiler, and in 1728 to Nassau-Usingen, thereby losing its status as a residence town, although it became the seat of the Nassau Archives and of an Oberamt.

In the 1170s, the Count of Nassau, Walram I, received the area around Wiesbaden as a fiefdom. In 1232, Wiesbaden became a Reichsstadt, an imperial city, of the Holy Roman Empire. Wiesbaden returned to the control of the House of Nassau in 1270 under Count Walram II, Count of Nassau. However, Wiesbaden and the castle at Sonnenberg were again destroyed in 1283 in conflict with Eppstein.

Walram's son and successor Adolf was, as said above, king of Germany from 1292 until 1298. In 1329, under Adolf's son Gerlach I of Nassau-Weilburg the House of Nassau and thereby, Wiesbaden, received the right of coinage from Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Bavarian.

In 1355, the County of Nassau-Weilburg was divided among the sons of Gerlach. The County of Nassau's holdings would be subdivided many times among heirs, with the parts being brought together again whenever a line died out. Wiesbaden became the seat of the County of Nassau-Wiesbaden under Count Adolf I (1307–1370), eldest son of Gerlach. It eventually fell back to Nassau-Weilburg in 1605.

-

Idstein Castle

Counts of Nassau-Saarbrücken (1429–1797)

Philipp I ruled both Nassau-Saarbrücken and Nassau-Weilburg and in 1393 inherited through his wife Johanna of Hohenlohe the lordships Kirchheimbolanden and Stauf. He also received half of Nassau-Ottweiler in 1393 and other territories later during his reign. After his death in 1429 the territories around Saarbrücken and along the Lahn were kept united until 1442, when they were again divided among his sons into the lines Nassau-Saarbrücken (west of the Rhine) and Nassau-Weilburg (east of the Rhine), the so-called Younger line of Nassau-Weilburg.

In 1507, Count John Ludwig I significantly enlarged his territory. After his death in 1544 the county was split into three parts, the three lines (Ottweiler, Saarbrücken proper and Kirchheim) were all extinct in 1574 and all of Nassau-Saarbrücken was united with Nassau-Weilburg until 1629. This new division, however, was not executed until the Thirty Years' War was over and in 1651 three counties were established: Nassau-Idstein, Nassau-Weilburg and Nassau-Saarbrücken.

Only eight years later, Nassau-Saarbrücken was again divided into:

- Nassau-Saarbrücken proper, fell to Nassau-Ottweiler in 1723

- Nassau-Ottweiler, fell to Nassau-Usingen in 1728

- Nassau-Usingen

In 1735, Nassau-Usingen was divided again into Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Saarbrücken. In 1797 Nassau-Usingen finally inherited Nassau-Saarbrücken, it was (re-)unified with Nassau-Weilburg and raised to the Duchy of Nassau in 1806. The first Duke of Nassau was Frederick August of Nassau-Usingen who died in 1816. Wilhelm, Prince of Nassau-Weilburg inherits the Duchy of Nassau. But, territories of Nassau Saarbrücken was occupied by France in 1793 and was annexed as Sarre department in 1797. Finally County of Nassau-Saarbrücken was part of Prussia in 1814.

After Henry Louis's death, Nassau-Saarbrücken fell to Charles William, Prince of Nassau-Usingen until Adolph came of age in 1805.

Princes of Nassau-Usingen (1659–1816)

The origin of the county lies in the medieval county of Weilnau that was acquired by the counts of Nassau-Weilburg in 1602. That county was divided in 1629 into the lines of Nassau-Weilburg, Nassau-Idstein and Nassau-Saarbrücken that was divided only 30 years later in 1659. The emerging counties were Nassau-Saarbrücken, Nassau-Ottweiler and Nassau-Usingen. At the beginning of the 18th century, three of the Nassau lines died out and Nassau-Usingen became their successor (1721 Nassau-Idstein, 1723 Nassau-Ottweiler und 1728 Nassau-Saarbrücken). In 1735 Nassau-Usingen was divided again into Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Saarbrücken. In 1797 Nassau-Usingen inherited Nassau-Saarbrücken. In 1816, Nassau-Usingen merged with Nassau-Weilburg to form the Duchy of Nassau. See "Dukes of Nassau" above.

Following Frederick Augustus' death, the princely title was adopted (in pretense) by his half brother through an unequal marriage, Karl Philip. As head of the House in 1907, Wilhelm IV declared the Count of Merenberg non-dynastic; by extension, this would indicate that (according to Luxembourgish laws regarding the House of Nassau) this branch would assume the Salic headship of the house in 1965, following the death of the last male Count of Merenberg.[53]

-

Usingen Castle

The Ottonian line

The partition of the county of Nassau between Otto, and his older brother Walram (above), resulted in a permanent division between the 2 branches of the family. The Walramian branch tended to concentrate on their German lands, while the Ottonians, as we will see below, established themselves in the Netherlands and became great magnates, leaders of the Dutch Revolt, the stadtholders of the Dutch Republican government, and eventual kings of the Netherlands. This, however, was not before many divisions and reunitings. The first was between sons of Otto, with the main power base being centered around the caste of Dillenburg:

- 1255–1290: Otto I, Count of Nassau in Siegen, Dillenburg, Beilstein, and Ginsberg

- 1290–1303: Joint rule by Henry, John and Emicho I, sons of Otto I

In 1303, Otto's sons divided the possessions of the Ottonian line. Henry received Nassau-Siegen, John received Nassau-Dillenburg and Emicho I received Nassau-Hadamar. After John's death. Nassau-Dillenburg fell to Henry.

Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg

The Ottonian portion of the county of Nassau was divided and sub-divided, as shown in the genealogical charts below, several times, so that each son of the previous count would have a portion. Eventually, these lines would all die out in favor of the main branch of the family, which had established themselves in The Netherlands.

- Ottonian Nassau Fortresses

-

Dillenburg Castle

Counts of Nassau-Beilstein

The counts of Nassau in Beilstein were involved mostly in local/regional German affairs in their area of the Rhine.

In 1343, Nassau-Beilstein was split off from Nassau-Dillenburg. After John III's death, Nassau-Beilstein fell back to Nassau-Dillenburg. It was split off again in 1607 (see below) for George, who inherited the rest of Nassau-Dillenburg in 1620.

First Counts and Princes of Nassau-Hadamar

First House of Nassau-Siegen

The branch of Nassau-Siegen was a collateral line of the House of Nassau, and ruled in Siegen. The first Count of Nassau-Siegen was Henry I, Count of Nassau-Siegen (d. 1343), the elder son of Otto I, Count of Nassau. His son Otto II, Count of Nassau-Siegen ruled also in Dillenburg. In 1328, John, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg died unmarried and childless, and Dillenburg fell to Henry I of Nassau-Siegen. For counts of Nassau-Siegen in between 1343 and 1606, see "Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg" above.

Netherland Nassaus/Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau stems from the elder branch of the Ottonian Line. The connection was via Engelbert I, who offered his services to the Duke of Burgundy, married in 1403 Johanna van Polanen, the heiress of the barony of Breda, the lordship of den Lek and other lands in the duchy of Brabant at the mouth of the Rhine delta and the Scheldt river. As the Scheldt was the main trade artery in the Burgundian/Habsburg Netherlands during the time, the Netherand Nassaus benefitted from the commerce. These lands formed the core of the Nassau's Dutch possessions.

The importance of the Nassaus grew throughout the 15th and 16th century. Henry III of Nassau-Breda was appointed stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht by Emperor Charles V in the beginning of the 16th century. Henry married Claudia of Châlon-Orange from French Burgundy in 1515. Their son René of Chalon inherited in 1530 the independent and sovereign Principality of Orange from his mother's brother, Philibert of Châlon. As the first Nassau to be the Prince of Orange, René could have used "Orange-Nassau" as his new family name. However, his uncle, in his will, had stipulated that René should continue the use of the name Châlon-Orange. At René's death in 1544, he left all his lands to his cousin William of Nassau-Dillenburg, including the sovereign principality of Orange. This "William I of Orange", in English better known as William the Silent, became the founder of the House of Orange-Nassau and the leader of the Dutch Revolt that lead to the formation of the Dutch Republic as a separate sovereign nation.[1]: 10

Within the government of the Dutch Republic, The Prince of Orange was also not just another noble among equals in the Netherlands. First, he was the traditional leader of the nation in war and in rebellion against Spain. He was uniquely able to transcend the local issues of the cities, towns and provinces. He was also a sovereign ruler in his own right (see Prince of Orange article). This gave him a great deal of prestige, even in a republic. He was the center of a real court like the Stuarts and Bourbons, French speaking, and extravagant to a scale. It was natural for foreign ambassadors and dignitaries to present themselves to him and consult with him as well as to the States General to which they were officially credited. The marriage policy of the princes, allying themselves twice with the Royal Stuarts, also gave them acceptance into the royal caste of rulers.[54]: 76–77, 80

The house of Orange-Nassau was relatively unlucky in establishing a hereditary dynasty in an age that favoured hereditary rule. The Stuarts and the Bourbons came to power at the same time as the Oranges, the Vasas and Oldenburgs were able to establish a hereditary kingship in Sweden and Denmark, and the Hohenzollerns were able to set themselves on a course to the rule of Germany. The House of Orange was no less gifted than those houses, in fact, some might argue more so, as their ranks included some the foremost statesmen and captains of the time. Although the institutions of the United Provinces became more republican and entrenched as time went on, William the Silent had been offered the countship of Holland and Zealand, and only his assassination prevented his accession to those offices. This fact did not go unforgotten by his successors.[1]: 28–31, 64, 71, 93, 139–141

Besides showing the relationships among the family, the tree above then also points out an extraordinary run of bad luck. In the 211 years from the death of William the Silent to the conquest by France, there was only one time that a son directly succeeded his father as Prince of Orange, Stadholder and Captain-General without a minority (William II). When the Oranges were in power, they also tended to settle for the actualities of power, rather than the appearances, which increasingly tended to upset the ruling regents of the towns and cities. On being offered the dukedom of Gelderland by the States of that province, William III let the offer lapse as liable to raise too much opposition in the other provinces.[54]: 75–83

The main house of Orange-Nassau also spawned several illegitimate branches. These branches contributed to the political and economic history of England and the Netherlands. Justinus van Nassau was the only extramarital child of William of Orange. He was a Dutch army commander known for unsuccessfully defending Breda against the Spanish, and the depiction of his surrender on the famous picture by Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda. Louis of Nassau, Lord of De Lek and Beverweerd was a younger illegitimate son of Prince Maurice and Margaretha van Mechelen. His descendants were later created Counts of Nassau-LaLecq. One of his sons was the famous general Henry de Nassau, Lord of Overkirk, King William III's Master of the Horse, and one of the most trusted generals of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. His descendants became the Earls of Grantham in England. Frederick van Nassau, Lord of Zuylestein, an illegitimate son of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, gave rise to the Earls of Rochford in England. The 4th earl of Rochford was a famous English diplomat and a statesman.

With the death of William III, the legitimate direct male line of William the Silent became extinct and thereby the first House of Orange-Nassau. John William Friso, the senior agnatic descendant of William the Silent's brother and a cognatic descendant of Frederick Henry, grandfather of William III, inherited the princely title and all the possessions in the low countries and Germany, but not the Principality of Orange itself. Orange had been invaded and captured by King Louis XIV in 1672 during the Franco-Dutch War, and again in August 1682, but William did not concede his claim to rule, and recovered the principality via the peace treaties. Louis again invaded and captured the principality in 1702. He enfeoffed François Louis, Prince of Conti, a Bourbon relative of the Châlon dynasty, with the Principality of Orange, so that there were three claimants to the title. The Principality was finally ceded to France under the Treaty of Utrecht that ended the wars with King Louis XIV. Frederick I of Prussia ceded the Principality to France (without surrendering the princely title), though John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz, the other claimant to the principality, did not concur. Only with the treaty of partition in 1732 did John William Friso's successor William IV, Prince of Orange, renounce all his claims to the territory, but again (like Frederick I) he did not renounce his claim to the title. In the same treaty an agreement was made between both claimants, stipulating that both houses be allowed to use the title.[55] John William Friso, who also was the Prince of Nassau-Dietz, founded thereby the second House of Orange-Nassau (the suffix name "Dietz" was dropped of the combined name Orange-Nassau-Dietz).

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic era was a tumultuous episode of the history of both the Ottonian and Walramian branches of the House of Nassau. France's dominance of the international order severely strained the House of Nassau's traditional strategy of international conflict resolution, which was to maintain links with all serious power-brokers through a dynastic network in the hope of playing one off against the other. Despite that both branches of the House of Nassau reinvigorated the dynastic network in the years of liberation, 1812–1814, the post-Napoleonic European order saw both branches set on different historical paths.[56]

After the post-Napoleonic reorganization of Europe, the head of House of Orange-Nassau became "King/Queen of the Netherlands".

Princes of Orange

House of Orange-Nassau

- 1544–1584: William I, also Count of Katzenelnbogen, Vianden, Dietz, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc.

- 1584–1618: Philip William, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc.

- 1618–1625: Maurice, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1625–1647: Frederick Henry, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1647–1650: William II, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc., Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1650–1702: William III, also Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam, Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc., Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic, and (from 1689) King of England, Scotland, and Ireland

In 1702, the Orange-Nassau line ended with King William III. He named his cousin John William Friso of Nassau-Dietz as his heir in The Netherlands and the principality of Orange, passing over the claims of the Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg/Prussia.

Second House of Orange-Nassau(-Dietz)

- 1702–1711: John William Friso, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1711–1751: William IV, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1751–1806: William V, also Prince of Nassau-Dietz, Count of Vianden, Buren and Leerdam and Lord of IJsselstein, Baron of Breda, etc. Stadholder of Holland, Zealand and Utrect, etc., Captain-General of the Armies of the Dutch Republic.

- 1806–1815: William VI, also Prince of Fulda and Count of Corvey, Weingarten and Dortmund; in 1815 became King William I of the Netherlands

Kings and Queens of the Netherlands (from the House of Orange-Nassau-Dietz)

- 1815–1840: William I, also Duke and Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1840–1849: William II, also Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1849–1890: William III, also Grand Duke of Luxemburg and Duke of Limburg

- 1890–1948: Wilhelmina

Following the laws of the Holy Roman Empire (which was abolished in 1806), the House of Orange-Nassau(-Dietz) has been extinct since the death of Wilhelmina (1962). Dutch laws and the Dutch nation do not consider it extinct.

- 1948–1980: Juliana

- 1980–2013: Beatrix

- 2013–present: Willem-Alexander

-

Noordeinde Palace, Den Haag

-

Huis ten Bosch, Den Haag

Younger lines of the Ottonian House of Nassau, 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries

When William the Silent inherited the lands of the Netherland Nassaus and the Principality of Orange, the German lands in the county of Nassau went to his younger brother, Jan VI, as shown below, and were subdivided amongst his surviving sons in 1606. A good many of these maintained ties with the Dutch Republic and served as stadholders and officers in the Dutch States Army.

Counts of Nassau-Dillenburg, continuation

The counts of Nassau in Dillenburg were the continuation of the main line of the Ottonian counts of Nassau, although only the 2nd oldest after The Netherlands Nassaus/house of Orange-Nassau. John VI is called the "elder", but this is not in relation to his older brother William the Silent, but in relation to his son, John VII "the Middle" and his grandson, John VIII "the younger". In the male line, the kings of The Netherlands spring from John VI until Queen Wilhelmina abdicated in 1948. John VI played a leading role during the Dutch Revolt: he was the principal author of the Union of Utrecht, which was the constitution of the Dutch Republic. He also served as stadholder of Utrect and Gelderland when they were reconquered from the Spanish. His eldest son, William Louis "Us Heit" (West Frisian for "our father") was Stadholder of Friesland, Groningen, and Drenthe, a General in the Dutch States Army and the chief lieutenant of his cousin Prince Maurice of Nassau, in their innovations in military strategy and organization, victories in the field, and governing of the Dutch Republic.

Second House of Nassau-Dietz

The counts (later princes in 1650) of Nassau-Dietz continued their service to the Dutch Republic. After the death of William Louis (see Second House of Nassau-Dillenburg) they were usually elected Stadholder of Friesland, Groningen, and Drenthe. They also served as senior Generals in the Dutch States Army.

In his will, William III appointed John William Friso as his heir in The Netherlands (his lordships being his property to dispose of by law) as well as his heir to the principality of Orange, the principality being a sovereign state, and so his right to appoint his successor. This was contested by the House of Hohenzollern, kings of Prussia, and not finally settled until the mid 18th century. In any case, the succession was in the title only, as Louis XIV of France had conquered the actual territory.

-

Diez Castle

-

Oranienstein Castle, Diez

Second House of Nassau-Hadamar

In 1620, the younger line of Nassau-Hadamar was split off from Nassau-Dillenburg, as shown below. John Louis, the first count, was a diplomat, who tried to protect his county from the ravages of the Thirty Years War. In 1647, for his efforts in bringing about peace between Spain and the Netherlands, King Philip IV of Spain appointed him a knight in the Order of the Golden Fleece. In addition, as a special thanks for his role in establishing the Peace of Westphalia, he was elevated to the rank of prince in 1650 by Emperor Ferdinand III. He did convert to Catholicism, so that Hadamar was Catholic after that.

Second House of Nassau-Siegen

In 1606, the younger line of Nassau-Siegen was split off from the House of Nassau-Dillenburg for John VII "the Middle". As Dillenburg eventually was inherited by a younger son of John VI (see below), the line of Nassau-Siegen became the elder line of the Ottonian House of Nassau. After John VII of Nassau-Siegen died in 1628, the land was divided:

- His eldest son, John VIII "the Younger", had converted to Catholicism and joined the Spanish Army. This caused a rivalry between him and his brother John Maurice below. The result was that Siegen was split. John VIII received the part of the county south of the river Sieg and the original castle in Siegen (which after 1695 was called the "Upper Castle"). John VIII was the founder of the Catholic line of Nassau-Siegen.

- John Maurice, who remained Protestant, was a soldier. He received the part of the county north of the Sieg. He was the founder of the Protestant line of Nassau-Siegen and he converted the former Franciscan monastery into a new residence, called the "Lower Castle", which was reconstructed after having burnt down at large parts in 1695. John Maurice spent most of his time away from Siegen, since he was governor of Dutch Brazil and later of the Prussian province of Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg. In 1668, he was appointed first field-marshal of the Dutch States Army, and in 1673, he was charged by the Stadtholder William III to command the forces in Friesland and Groningen, and to defend the eastern frontier of the provinces, again against Van Galen. In 1675, his health compelled him to give up active military service, and he spent his last years in his beloved Cleves, where he died in December 1679. Between 1638 and 1674, his brother George Frederick ruled the Protestant part of the country.

In 1652, John Francis Desideratus of the Catholic line was elevated to Imperial Prince. Count Henry of the Protestant line married Mary Magdalene of Limburg-Stirum, who brought the Lordship of Wisch in the County of Zutphen into the marriage. In 1652, John Maurice of the Protestant line was also elevated to Imperial Prince.

In 1734, the Protestant line died out with the death of Frederick William II. Protestant Nassau-Siegen was annexed by Christian of Nassau-Dillenburg and William IV of Nassau-Diez. When William Hyacinth, the last ruler of the Catholic line, died in 1743, Nassau-Siegen had died out in the male line, and the territory fell to Prince William IV of the Orange-Nassau-Dietz line, who thereby reunited all the lands of the Ottonian line of the House of Nassau.

| Elder (Catholic) Line | Younger (Protestant) Line | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| John VII | 1606–1623 | |

| John VIII | 1623–1638 | |

| William | 1624–1642 | |

| John Maurice | 1632–1636 | |

| John Francis Desideratus | 1638–1699 | |

| John Maurice | 1642–1679 | |

| William Maurice | 1679–1691 | |

| Frederick William Adolf | 1691–1722 | |

| William Hyacinth | 1699–1743 | |

| Frederick William II | 1722–1734 | |

| annexed by Nassau-Dillenburg and Orange-Nassau(-Dietz) | 1734 | |

| inherited by Orange-Nassau(-Dietz) | 1743 |

Overview of Nassau coats of arms

Background and origins

The ancestral coat of arms of the Ottonian line of the house of Nassau is shown below. Their distant cousins of the Walramian line added a red coronet to distinguish them. There is no documentation on how and why these arms came to be. As a symbol of nobility, the lion was always a popular in western culture going all the way back to Hercules. Using the heraldic insignia of a dominant power was a way, and still is a way, to show loyalty to that power. Not using that insignia is a way to show independence. The Netherlands, as territories bordering on the Holy Roman Empire with its Roman eagle and France with its Fleur-de-lis, had many examples of this. The lion was so heavily used in the Netherlands for various provinces and families (see Leo Belgicus) that it became the national arms of the Dutch Republic, its successor states the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Blue, because of its nearness to purple, which in the northern climes tended to fade (red was the other choice), was also a popular color for those with royal aspirations. The billets could have been anything from blocks of wood to abstractions of the reinforcements holding the shield together. The fact that these were arms were very similar to those of the counts of Burgundy (Franche-Comté) did not seem to cause too much confusion. It also held with one of the basic tenants of heraldry, that arms could not be repeated within a kingdom, but Nassau was considered to be in the Kingdom of Germany, while Franche-Comté was in the kingdom of Burgundy (see also Scrope v Grosvenor).[58][59]

Coats of arms of sovereignty also show the territories that the dynasty claims to rule over. The principle ones are depicted below, i.e.

- The Principality of Orange, which gave them their major title and claim to equal status with all the other sovereign rulers of the world, Prince of Orange.

Then,

- The Lordship of Chalons and Arlay, a large set of lands in the Franche-Comté

- The County of Geneva

And in Germany,

- County of Katzenelnbogen a large set of lands near the County of Nassau

- The County of Dietz, also near the County of Nassau

- County of Meurs, bordering on the northeastern Netherlands

Finally, in the Netherlands, the real base of their wealth and power:

- County of Vianden, in the southern Netherlands along the river Meuse.

- Marquisate of Vlissingen (Flushing) and KampenVeere, which sat along the mouth of the Rhine and the trade routes across the North Sea and the world beyond.

- County of Buren, also long the delta of the Rhine, but further inland.

In most of the estates in the more populous provinces of Holland and Zealand, the land itself was secondary to the profit on the commerce that flowed through it.

| Arms of dynastic founders | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Ottonian (Younger) Line | Walramian (Elder) Line |

| Arms of the dominions of the Princes of Orange | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Prince of Orange | Lords of Chalons and Arlay | Counts of Geneva | |

|

|

| |

| Counts of Katzenelnbogen | County of Dietz | Counts of Vianden | |

|

|

| |

| Marquis of Vlissingen (Flushing) and KampenVeere | Count of Buren | Count of Meurs | |

Arms of branches

| Arms of the Grand Dukes of Luxembourg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arms of Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany/King of the Romans (1292–1298) | Arms of the Grand Duke of Luxembourg (1890–1898)[60] | Arms of the Grand Duke of Luxembourg (1898–2000)[60] | Arms of the Grand Duke of Luxembourg (2000–present).[61][62] | Personal Arms of the Grand Duke of Luxembourg (2000–present).[63][62] |

| Arms of the Princes of Orange | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arms of René of Chalon and Nassau as Prince of Orange, 1530–1544[64] | Arms of the Prince of Orange 1544–1582, 1584–1618[65][66] | Arms of the Prince of Orange, 1582–1584, 1625–1702[67][65][68] | Alternate arms of the Prince of Orange[67][69] | Arms of William III as King of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1688–1702[70] |

| Arms of the Kings of the Netherlands | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Arms of the King of the Netherlands, 1815–1907[71] | Arms of the Queens and King of the Netherlands, 1907–present[72] | Arms of the Prince of Orange/Crown Prince of the Netherlands, 1980–2013[73][74] | Arms of the Princess of Orange/Crown Princess of the Netherlands, 2013–present[75][76] |

Family tree

| Family tree of the House of Nassau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||