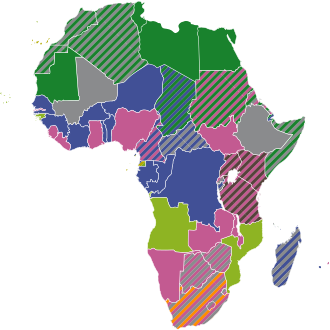

Languages of Africa

There are 1,250 to 2,100[1] and by some counts over 3,000 languages spoken natively in Africa.[2] They are divided into six major language families:

- Afroasiatic languages are spread throughout the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of the Sahel.

- Austronesian languages are spoken in Madagascar.

- Indo-European languages are spoken on the southern tip of the continent (Afrikaans), as well as in the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla (Spanish) in the north.

- Khoe languages are concentrated in the deserts of Namibia and Botswana.

- Niger–Congo (Bantu and non-Bantu) covers West, Central, Southeast and Southern Africa.

- Nilo-Saharan languages are centered on Sudan and Chad (disputed validity).

There are several other small families and language isolates, as well as languages that have yet to be classified. In addition, Africa has a wide variety of sign languages, many of which are language isolates (see below).

Around a hundred of the languages of Africa are widely used for inter-ethnic communication. Arabic, Somali, Berber, Amharic, Oromo, Swahili, Hausa, Manding, Fulani and Yoruba are spoken by tens of millions of people. If clusters of up to a hundred similar languages are counted together, twelve are spoken by 75 percent, and fifteen by 85 percent, of Africans as a first or additional language.[3]

The high linguistic diversity of many African countries (Nigeria alone has over 500 languages,[4] one of the greatest concentrations of linguistic diversity in the world) has made language policy a vital issue in the post-colonial era. In recent years, African countries have become increasingly aware of the value of their linguistic inheritance. Language policies being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism. For example, all African languages are considered official languages of the African Union (AU). 2006 was declared by the African Union as the "Year of African Languages".[5] However, although many mid-sized languages are used on the radio, in newspapers, and in primary-school education, and some of the larger ones are considered national languages, only a few are official at the national level.

Language groups

Most languages spoken in Africa belong to one of three large language families: Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan, and Niger–Congo. Another hundred belong to small families such as Ubangian (sometimes grouped within Niger-Congo) and the various families called Khoisan, or the Indo-European and Austronesian language families which originated outside Africa; the presence of the latter two dates to 2,600 and 1,500 years ago, respectively. In addition, the languages of Africa languages include several unclassified languages and sign languages.

Afroasiatic languages

Afroasiatic languages are spoken throughout North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Sahel. There are approximately 375 Afroasiatic languages spoken by over 350 million people. The main subfamilies of Afroasiatic are the Berber languages, Semitic languages, Chadic languages and the Cushitic languages. The Afroasiatic Urheimat is uncertain. However, its most extensive sub-branch, the Semitic languages (including Arabic, Amharic and Hebrew among others), seems to have developed in the Arabian peninsula. The Semitic languages are the only branch of the Afroasiatic family of languages that is spoken outside of Africa.

Some of the most widely spoken Afroasiatic languages include Arabic (a Semitic language, and a recent arrival from West Asia), Somali (Cushitic), Berber (Berber), Hausa (Chadic), Amharic (Semitic), and Oromo (Cushitic). Of the world's surviving language families, Afroasiatic has the longest written history, as both the Akkadian language of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egyptian are members.

Nilo-Saharan languages

Nilo-Saharan is a controversial grouping uniting over a hundred extremely diverse languages. It has a speech area that stretches from the Nile Valley to northern Tanzania and into Nigeria and DR Congo, with the Songhay languages along the middle reaches of the Niger River as a geographic outlier. Genetic linkage between these languages has not been conclusively demonstrated, and among linguists, support for the proposal is sparse.[6][7] The languages share some unusual morphology, but if they are related, most of the branches must have undergone major restructuring since diverging from their common ancestor. The inclusion of the Songhay languages is questionable, and doubts have been raised over the Koman, Gumuz, and Kadu branches.

Some of the better known Nilo-Saharan languages are Kanuri, Fur, Songhay, Nobiin, and the widespread Nilotic family, which includes the Luo, Dinka, and Maasai. The Nilo-Saharan languages are tonal.

Niger–Congo languages

The Niger–Congo family is the largest language group spoken in Africa and perhaps the world in terms of the number of languages. One of its salient features is an elaborate noun class system with grammatical concord. The vast majority of languages of this family are tonal such as Yoruba and Igbo, Ashanti, and Ewe language. A major branch of Niger–Congo languages is the Bantu family, which covers a greater geographic area than the rest of the family put together (see Niger–Congo B (Bantu) in the map above).

The Niger–Kordofanian language family, joining Niger–Congo with the Kordofanian languages of south-central Sudan, was proposed in the 1950s by Joseph Greenberg. Today, linguists often use "Niger–Congo" to refer to this entire family, including Kordofanian as a subfamily. One reason for this is that it is not clear whether Kordofanian was the first branch to diverge from rest of Niger–Congo. Mande has been claimed to be equally or more divergent. Niger–Congo is generally accepted by linguists, though a few question the inclusion of Mande and Dogon, and there is no conclusive evidence for the inclusion of Ubangian.

Other language families

Austronesian

Several languages spoken in Africa belong to language families concentrated or originating outside of the African continent. For example, Malagasy, the language of Madagascar, belongs to the Austronesian family.

Indo-European

Afrikaans is Indo-European, as are the lexifiers of most African creole languages. Afrikaans is the only Indo-European language known to have developed in Africa; thus, it is an African language. Afrikaans is spoken throughout Southern Africa. Most Afrikaans speakers live in South Africa, in Namibia it is the lingua franca and in Botswana and Zimbabwe it is a minority language of roughly several ten thousand people. Over the entire world 15 to 20 million people are estimated to speak Afrikaans.

Since the colonial era, Indo-European languages such as Afrikaans, English, French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish have held official status in many countries, and are widely spoken, generally as lingua francas. (See African French and African Portuguese.) German was once used in Germany's colonies there from the late 1800s until World War I, when Britain and France took over and revoked German's official status. Despite this, German is still spoken in Namibia, mostly among the white population. Although it lost its official status in the '90s, it has been redesignated as a national language. Indian languages such as Gujarati are spoken by South Asian expatriates exclusively. In earlier historical times, other Indo-European languages could be found in various parts of the continent, such as Old Persian and Greek in Egypt, Latin and Vandalic in North Africa, and Modern Persian in the Horn of Africa.

Small families

The three small Khoisan families of southern Africa have not been shown to be closely related to any other major language family. In addition, there are various other families that have not been demonstrated to belong to one of these families. (The questionable branches of Nilo-Saharan were covered above, and are not repeated here.)

- Mande, some 70 languages, including the major languages of Mali and Guinea. These are generally thought to be divergent Niger–Congo, but debate persists.

- Ubangian, some 70 languages, including the languages of the Central African Republic. May also be Niger–Congo.

- Khoe, about 10 languages, the primary family of Khoisan languages of Namibia and Botswana

- Sandawe, an isolate of Tanzania, possibly related to Khoe

- Kx'a, a language of Southern Africa

- Tuu, or Taa-Ui, two surviving languages

- Hadza, an isolate of Tanzania

- Bangi-me, a likely isolate of Mali

- Jalaa, a likely isolate of Nigeria

- Laal, a possible isolate of Chad

Khoisan is a term of convenience covering some 30 languages spoken by around 300,000–400,000 people. There are five Khoisan families that have not been shown to be related to each other: Khoe, Tuu, and Kx'a (these are found mainly in Namibia and Botswana), as well as Sandawe and Hadza of Tanzania, which are language isolates. A striking feature of Khoisan languages, and the reason they are often counted together, is their use of click consonants. Some neighboring Bantu languages (notably Xhosa and Zulu) have clicks as well, but these were adopted from Khoisan languages. The Khoisan languages are also tonal.

Creole languages

Due partly to its multilingualism and its colonial past, a substantial proportion of the world's creole languages are to be found in Africa. Some are based on Indo-European languages (e.g. Krio from English in Sierra Leone and the very similar Pidgin in Nigeria and parts of Cameroon, Cape Verdean Creole in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau Creole in Guinea-Bissau and Senegal both from Portuguese, Seychellois Creole from French in the Seychelles, or Mauritian Creole in Mauritius); some are based on Arabic (e.g. Juba Arabic in the southern Sudan, or Nubi in parts of Uganda and Kenya); some are based on local languages (e.g. Sango, the main language of the Central African Republic); while in Cameroon a creole based on French, English and local African languages known as Camfranglais has started to become popular.

Unclassified languages

A fair number of unclassified languages are reported in Africa. Many remain unclassified simply for lack of data; among the better-investigated ones that continue to resist easy classification are:

- possibly Afroasiatic: Ongota, Gomba

- possibly Nilo-Saharan: Shabo

- possibly Niger–Congo: Jalaa, Mbre, Bayot

- possibly Khoe: Kwadi

- unknown: Laal, Mpre

Of these, Jalaa is perhaps the most likely to be an isolate.

Less-well investigated languages include Irimba, Luo, Mawa, Rer Bare (possibly Bantu), Bete (evidently Jukunoid), Bung (unclear), Kujarge (evidently Chadic), Lufu (Jukunoid), Meroitic (possibly Afroasiatic), Oropom (possibly spurious), and Weyto (evidently Cushitic). Several of these are extinct, and adequate comparative data is thus unlikely to be forthcoming. Hombert & Philippson (2009)[8] list a number of African languages that have been classified as language isolates at one point or another. Many of these are simply unclassified, but Hombert & Philippson believe Africa has about twenty language families, including isolates. Beside the possibilities listed above, there are:

- Aasax or Aramanik (Tanzania) (South Cushitic? contains non-Cushitic lexicon)

- Imeraguen (Mauritania) - Hassaniyya Arabic restructured on an Azêr (Soninke) base

- Kara (Fer?) (Central African Republic)

- Oblo (Cameroon) (Adamawa? Extinct?)

Roger Blench notes a couple additional possibilities:

Sign languages

Many African countries have national sign languages, such as Algerian Sign Language, Tunisian Sign Language, Ethiopian Sign Language. Other sign languages are restricted to small areas or single villages, such as Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana. Tanzania has seven, one for each of its schools for the Deaf, all of which are discouraged. Not much is known, since little has been published on these languages

Sign language systems extant in Africa include the Paget Gorman Sign System used in Namibia and Angola, the Sudanese Sign languages used in Sudan and South Sudan, the Arab Sign languages used across the Arab Mideast, the Francosign languages used in Francophone Africa and other areas such as Ghana and Tunisia, and the Tanzanian Sign languages used in Tanzania.

Language in Africa

Throughout the long multilingual history of the African continent, African languages have been subject to phenomena like language contact, language expansion, language shift, and language death. A case in point is the Bantu expansion, in which Bantu-speaking peoples expanded over most of Sub-Equatorial Africa, displacing Khoi-San speaking peoples from much of Southeast Africa and Southern Africa and other peoples from Central Africa. Another example is the Arab expansion in the 7th century, which led to the extension of Arabic from its homeland in Asia, into much of North Africa and the Horn of Africa.

Trade languages are another age-old phenomenon in the African linguistic landscape. Cultural and linguistic innovations spread along trade routes and languages of peoples dominant in trade developed into languages of wider communication (lingua franca). Of particular importance in this respect are Berber (North and West Africa), Jula (western West Africa), Fulfulde (West Africa), Hausa (West Africa), Lingala (Congo), Swahili (Southeast Africa), Somali (Horn of Africa) and Arabic (North Africa and Horn of Africa).

After gaining independence, many African countries, in the search for national unity, selected one language, generally the former colonial language, to be used in government and education. However, in recent years, African countries have become increasingly supportive of maintaining linguistic diversity. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism.

Official Languages

Besides the former colonial languages of English, French, Portuguese and Spanish, the following languages are official at the national level in Africa (non-exhaustive list):

- Afroasiatic

- Arabic in Comoros, Chad, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Mauritania,[9] Somalia,[10] Sudan, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya and Morocco

- Berber in Morocco and Algeria

- Amharic in Ethiopia

- Somali in Somalia

- Tigrinya in Eritrea

- Austronesian

- Indo-European

- Niger-Congo

- Chewa in Malawi and Zimbabwe

- Comorian in the Comoros

- Kinyarwanda in Rwanda

- Kirundi in Burundi

- Sesotho in Lesotho, South Africa, and Zimbabwe

- Setswana/Tswana in Botswana and South Africa

- Shona, Sindebele in Zimbabwe

- Sepedi in South Africa

- Ndebele in South Africa[11]

- Swahili in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda

- Swati in Swaziland and South Africa

- Tsonga in South Africa

- Venda in South Africa

- Xhosa in South Africa

- Zulu in South Africa

- Creoles

- Sango in the Central African Republic

- Seychellois Creole in the Seychelles

Cross-border languages

The colonial borders established by European powers following the Berlin Conference in 1884–1885 divided a great many ethnic groups and African language speaking communities. In a sense, "cross-border languages" is a misnomer[citation needed]—the speakers did not divide themselves. Nevertheless, it describes the reality of many African languages, which has implications for divergence of language on either side of a border (especially when the official languages are different), standards for writing the language, etc. Some notable cross-border languages include Berber (which stretches across much of North Africa and some parts of West Africa), Somali (stretches across most of the Horn of Africa), Swahili (spoken in the African Great Lakes region) and Fula (in the Sahel and West Africa).

Some prominent Africans such as former Malian president and former Chairman of the African Commission, Alpha Oumar Konaré, have referred to cross-border languages as a factor that can promote African unity.[12]

Language change and planning

Language is not static in Africa any more than on other continents. In addition to the (likely modest) impact of borders, there are also cases of dialect levelling (such as in Igbo and probably many others), koinés (such as N'Ko and possibly Runyakitara), and emergence of new dialects (such as Sheng). In some countries, there are official efforts to develop standardized language versions.

There are also many less widely spoken languages that may be considered endangered languages.

Demographics

Of the 1 billion Africans (in 2009), about 17 percent speak an Arabic dialect[citation needed]. About 10 percent speak Swahili[citation needed], the lingua franca of Southeast Africa; about 5 percent speak a Berber dialect[citation needed]; and about 5 percent speak Hausa, which serves as a lingua franca in much of the Sahel. Other important West African languages are Yoruba, Igbo and Fula. Major Horn of Africa languages are Amharic, Oromo and Somali. Important South African languages are Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans.[13]

English, French, and Portuguese are important languages in Africa: 130, 115, 30 million Africans speak them as either native or secondary languages. Portuguese has become the national language of Angola.[14] Through (among other factors) sheer demographic weight, Africans are increasingly taking ownership [citation needed] of these three world languages and having an ever greater influence on their development and growth.

Linguistic features

Some linguistic features are particularly common among languages spoken in Africa, whereas others are less common. Such shared traits probably are not due to a common origin of all African languages. Instead, some may be due to language contact (resulting in borrowing) and specific idioms and phrases may be due to a similar cultural background.

Phonological

Some widespread phonetic features include:

- certain types of consonants, such as implosives (/ɓa/), ejectives (/kʼa/), the labiodental flap, and in southern Africa, clicks (/ǂa/, /ᵑǃa/). True implosives are rare outside Africa, and clicks and the flap almost unheard of.

- doubly articulated labial-velar stops like /k͡pa/ and /ɡ͡ba/ are found in places south of the Sahara.

- prenasalized consonants, like /mpa/ and /ŋɡa/, are widespread in Africa but not common outside it.

- sequences of stops and fricatives at the beginnings of words, such as /fsa/, /pta/, and /dt͡sk͡xʼa/.

- nasal stops which only occur with nasal vowels, such as [ba] vs. [mã] (but both [pa] and [pã]), especially in West Africa.

- vowels contrasting an advanced or retracted tongue, commonly called "tense" and "lax".

- simple tone systems which are used for grammatical purposes.

Sounds that are relatively uncommon in African languages include uvular consonants, diphthongs, and front rounded vowels

Tonal languages are found throughout the world but are especially numerous in Africa. Both the Nilo-Saharan and the Khoi-San phyla are fully tonal. The large majority of the Niger–Congo languages is also tonal. Tonal languages are also found in the Omotic, Chadic, and South & East Cushitic branches of Afroasiatic. The most common type of tonal system opposes two tone levels, High (H) and Low (L). Contour tones do occur, and can often be analysed as two or more tones in succession on a single syllable. Tone melodies play an important role, meaning that it is often possible to state significant generalizations by separating tone sequences ("melodies") from the segments that bear them. Tonal sandhi processes like tone spread, tone shift, and downstep and downdrift are common in African languages.

Syntactic

Widespread syntactical structures include the common use of adjectival verbs and the expression of comparison by means of a verb 'to surpass'. The Niger–Congo languages have large numbers of genders (noun classes) which cause agreement in verbs and other words. Case, tense, and other categories may be distinguished only by tone.

Semantic

Quite often, only one term is used for both animal and meat; the word nama or nyama for animal/meat is particularly widespread in otherwise widely divergent African languages.

Number of speakers

The following is a table displaying the number of speakers of a given language in Africa only.

See also

General

Works

Classifiers

Notes

- ^ Heine, Bernd; Heine, Bernd, eds. (2000). African Languages: an Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Epstein, Edmund L.; Kole, Robert, eds. (1998). The Language of African Literature. Africa World Press. p. ix. ISBN 0-86543-534-0. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

Africa is incredibly rich in language—over 3,000 indigenous languages by some counts, and many creoles, pidgins, and lingua francas.

- ^ "HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2004" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2004.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Nigeria". Ethnologue Languages of the World.

- ^ African Union Summit 2006 Khartoum, Sudan. SARPN.

- ^ Lyle Campbell & Mauricio J. Mixco, A Glossary of Historical Linguistics (2007, University of Utah Press)

- ^ P.H. Matthews, Oxford Concise Dictionary of Linguistics (2007, 2nd edition, Oxford)

- ^ Jean-Marie Hombert & Gérard Philippson. 2009. "The linguistic importance of language isolates: the African case." In Peter K. Austin, Oliver Bond, Monik Charette, David Nathan & Peter Sells (eds). Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory 2. London: SOAS.

- ^ CIA – The World Factbook.

- ^ According to article 7 of The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic: “The official languages of the Somali Republic shall be Somali (Maay and Maxaatiri) and Arabic. The second languages of the Transitional Federal Government shall be English and Italian.”

- ^ "The languages of South Africa". southafrica.info.

- ^ African languages for Africa's development ACALAN (French & English).

- ^ The Economist, "Tongues under threat", 22 January 2011, p. 58.

- ^ "The Embassy of the Republic of Angola - Culture".

- ^ "Census 2011 – Home language" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nationalencyklopedin "Världens 100 största språk 2007" The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007

- ^ "Amharic".

- ^ "Arabic".

- ^ "Gikuyu".

- ^ Ethnologue (2009) cites 18,5 million L1 and 15 million L2 speakers in Nigeria in 1991; 5.5 million L1 speakers and half that many L2 speakers in Niger in 2006, 0.8 million in Benin in 2006, and just over 1 million in other countries.

- ^ "Ibo - Language Information & Resources".

- ^ "Kongo".

- ^ "Malagasy".

- ^ "Ndebele". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Sotho, Northern".

- ^ "The Future of Portuguese - The Translation Company".

- ^ "Sotho, Southern".

- ^ Maaroufi, Youssef. "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitat 2004".

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Shona (S.10)".

- ^ "Somali". SIL International. 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Peek, Philip M.; Kwesi Yankah (2004). African folklore: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 699. ISBN 0-415-93933-X.

- ^ "Tigrigna".

- ^ "Luba-Kasai".

- ^ "Tswana".

- ^ "Umbundu".

References

- Childs, G. Tucker (2003). An Introduction to African Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamin.

- Chimhundu, Herbert (2002). Language Policies in Africa. (Final report of the Intergovernmental Conference on Language Policies in Africa.) Revised version. UNESCO.

- Cust, Robert Needham (1883). Modern Languages of Africa.

- Ellis, Stephen (ed.) (1996). Africa Now: People - Policies - Institutions. The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS).

- Elugbe, Ben (1998) "Cross-border and major languages of Africa." In K. Legère (editor), Cross-border Languages: Reports and Studies, Regional Workshop on Cross-Border Languages, National Institute for Educational Development (NIED), Okahandja, 23–27 September 1996. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan.

- Ethnologue.com's Africa: A listing of African languages and language families.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1983). 'Some areal characteristics of African languages.' In Ivan R. Dihoff (editor), Current Approaches to African Linguistics, Vol. 1 (Publications in African Languages and Linguistics, Vol. 1), Dordrecht: Foris, 3-21.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1966). The Languages of Africa (2nd edition with additions and corrections). Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Heine, Bernd and Derek Nurse (editors) (2000). African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Webb, Vic and Kembo-Sure (editors) (1998). African Voices: An Introduction to the Languages and Linguistics of Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

- Wedekind, Klaus ( Oxford University Press.

External links

- African language resources for children

- Web resources for African languages

- Linguistic maps of Africa from Muturzikin.com

- Online Dictionaries, e-books, and other online fulltexts in or on African languages