Love

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, or the deepest interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure.[1] An example of this range of meanings is that the love of a mother differs from the love of a spouse, which differs from the love of food. Most commonly, love refers to a feeling of strong attraction and emotional attachment.[2]

Love is considered to be both positive and negative, with its virtue representing human kindness, compassion, and affection—"the unselfish, loyal, and benevolent concern for the good of another"—and its vice representing a human moral flaw akin to vanity, selfishness, amour-propre, and egotism. It may also describe compassionate and affectionate actions towards other humans, oneself, or animals.[3] In its various forms, love acts as a major facilitator of interpersonal relationships, and owing to its central psychological importance, is one of the most common themes in the creative arts.[4][5] Love has been postulated to be a function that keeps human beings together against menaces and to facilitate the continuation of the species.[6]

Ancient Greek philosophers identified six forms of love: familial love (storge), friendly love or platonic love (philia), romantic love (eros), self-love (philautia), guest love (xenia), and divine or unconditional love (agape). Modern authors have distinguished further varieties of love: fatuous love, unrequited love, empty love, companionate love, consummate love, infatuated love (limerence), amour de soi, and courtly love. Numerous cultures have also distinguished Ren, Yuanfen, Mamihlapinatapai, Cafuné, Kama, Bhakti, Mettā, Ishq, Chesed, Amore, charity, Saudade (and other variants or symbioses of these states), as culturally unique words, definitions, or expressions of love in regard to specified "moments" currently lacking in the English language.[7]

The color wheel theory of love defines three primary, three secondary, and nine tertiary love styles, describing them in terms of the traditional color wheel. The triangular theory of love suggests intimacy, passion, and commitment are core components of love. Love has additional religious or spiritual meaning. This diversity of uses and meanings, combined with the complexity of the feelings involved, makes love unusually difficult to consistently define, compared to other emotional states.

Definitions

The word "love" can have a variety of related but distinct meanings in different contexts. Many other languages use multiple words to express some of the different concepts that in English are denoted as "love"; one example is the plurality of Greek concepts for "love" (agape, eros, philia, storge).[8] Cultural differences in conceptualizing love makes it difficult to establish a universal definition.[9]

Although the nature or essence of love is a subject of frequent debate, different aspects of the word can be clarified by determining what is not love (antonyms of "love"). Love, as a general expression of positive sentiment (a stronger form of like), is commonly contrasted with hate (or neutral apathy). As a less sexual and more emotionally intimate form of romantic attachment, love is commonly contrasted with lust. As an interpersonal relationship with romantic overtones, love is sometimes contrasted with friendship, although the word love is often applied to close friendships or platonic love. Further possible ambiguities come with usages like "girlfriend", "boyfriend", and "just good friends".

Abstractly discussed, love usually refers to a feeling one person experiences for another person. Love often involves caring for, or identifying with, a person or thing (cf. vulnerability and care theory of love), including oneself (cf. narcissism). In addition to cross-cultural differences in understanding love, ideas about love have also changed greatly over time. Some historians date modern conceptions of romantic love to courtly Europe during or after the Middle Ages, although the prior existence of romantic attachments is attested by ancient love poetry.[10]

The complex and abstract nature[clarification needed] of love often reduces its discourse to a thought-terminating cliché. Several common proverbs regard love, from Virgil's "Love conquers all" to The Beatles' "All You Need Is Love". St. Thomas Aquinas, following Aristotle, defines love as "to will the good of another."[11][12] Bertrand Russell describes love as a condition of[clarification needed] "absolute value," as opposed to relative value.[13] Philosopher Gottfried Leibniz said that love is "to be delighted by the happiness of another."[14] Meher Baba stated that in love there is a "feeling of unity" and an "active appreciation of the intrinsic worth of the object of love."[15] Biologist Jeremy Griffith defines love as "unconditional selflessness".[16] According to Ambrose Bierce, love is a temporary insanity curable by marriage.[17]

Impersonal

People can express love towards things other than humans; this can range from expressing a strong liking of something, such as "I love popcorn" or that something is essential to one's identity, such as "I love being an actor".[18]

People can have a profound dedication and immense appreciation for an object, principle, or objective, thereby experiencing a sense of love towards it. For example, compassionate outreach and volunteer workers' "love" of their cause may sometimes be born not of interpersonal love but impersonal love, altruism, and strong spiritual or political convictions.[3]

People can also "love" material objects, animals, or activities if they invest themselves in bonding or otherwise identifying with those things. If sexual passion is also involved, then this feeling is called paraphilia.[19]

Interpersonal

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

Interpersonal love refers to love between human beings. It is a much more potent sentiment than liking a person. Unrequited love refers to feelings of love that are not reciprocated. Interpersonal love is most closely associated with interpersonal relationships.[3] Such love might exist between family members, friends, and couples. There are several psychological disorders related to love, such as erotomania.

Throughout history, philosophy and religion have speculated about the phenomenon of love. In the 20th century, the science of psychology has studied the subject. The sciences of anthropology, neuroscience, and biology have also added to the understanding of the concept of love.

Biological basis

Biological models of sex tend to view love as a mammalian[clarification needed] drive, much like hunger or thirst.[20] Helen Fisher, an anthropologist and human behavior researcher, divides the experience of love into three partly overlapping stages: lust, attraction, and attachment. Lust is the feeling of sexual desire; romantic attraction determines what partners find attractive and pursue, conserving time and energy by choosing[clarification needed]; and attachment involves sharing a home, parental duties, mutual defense, and in humans involves feelings of safety and security.[21] Three distinct neural circuitries,[specify] including neurotransmitters,[specify] and three behavioral patterns,[specify] are associated with[how?] these three romantic styles.[21]

Lust is the initial passionate sexual desire that promotes mating, and involves the increased release of hormones such as testosterone and estrogen. These effects rarely last more than a few weeks or months. Attraction is the more individualized and romantic desire for a specific candidate for mating, which develops out of lust as commitment to an individual mate form. Recent studies in neuroscience have indicated that as people fall in love, the brain consistently releases a certain set of chemicals, including the neurotransmitter hormones dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, the same compounds released by amphetamine, stimulating the brain's pleasure center and leading to side effects such as increased heart rate, reduced appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement. Research indicates that this stage generally lasts from one and a half to three years.[22]

Since the lust and attraction stages are both considered temporary, a third stage is needed to account for long-term relationships. Attachment is the bonding that promotes relationships lasting for many years and even decades. Attachment is generally based on commitments such as marriage and children, or mutual friendship based on things like shared interests. It has been linked to higher levels of the chemicals oxytocin and vasopressin, to a greater degree than what is found in short-term relationships.[22] Enzo Emanuele and coworkers reported the protein molecule known as the nerve growth factor (NGF) has high levels when people first fall in love, but these return to previous levels after one year.[23]

Psychological basis

Psychology depicts love as a cognitive and social phenomenon. Psychologist Robert Sternberg formulated a triangular theory of love in which love has three components: intimacy, commitment, and passion. Intimacy is when two people share confidences and various details of their personal lives, and is usually shown in friendships and romantic love affairs. Commitment is the expectation that the relationship is permanent. Passionate love is shown in infatuation as well as romantic love. All forms of love are viewed as varying combinations of these three components. Non-love does not include any of these components. Liking only includes intimacy. Infatuated love only includes passion. Empty love only includes commitment. Romantic love includes both intimacy and passion. Companionate love includes intimacy and commitment. Fatuous love includes passion and commitment. Consummate love includes all three components.[24]

American psychologist Zick Rubin sought to define love by psychometrics in the 1970s. His work identifies a different set of three factors that constitute love: attachment, caring, and intimacy.[25]

Following developments in electrical theories such as Coulomb's law, which showed that positive and negative charges attract, analogs in human life were envisioned, such as "opposites attract". Research on human mating has generally found this not to be true when it comes to character and personality—people tend to like people similar to themselves. However, in a few unusual and specific domains, such as immune systems, it seems that humans prefer others who are unlike themselves (e.g., with an orthogonal immune system), perhaps because this will lead to a baby that has the best of both worlds.[26]

In recent years, various human bonding theories have been developed, described in terms of attachments, ties, bonds, and affinities. Some Western authorities disaggregate[clarification needed] into two main components, the altruistic and the narcissistic. This view is represented in the works of Scott Peck, whose work in the field of applied psychology explored the definitions of love and evil. Peck maintains that love is a combination of the "concern for the spiritual growth of another" and simple narcissism.[27] In combination, love is an activity, not simply a feeling.

Psychologist Erich Fromm maintained in his book The Art of Loving that love is not merely a feeling but is also actions, and that in fact the "feeling" of love is superficial in comparison to one's commitment to love via a series of loving actions over time.[3] Fromm held that love is ultimately not a feeling at all, but rather is a commitment to, and adherence to, loving actions towards another, oneself, or many others, over a sustained duration.[3] Fromm also described love as a conscious choice that in its early stages might originate as an involuntary feeling, but which then later no longer depends on those feelings, but rather depends only on conscious commitment.[3]

Evolutionary basis

Evolutionary psychology has attempted to provide various reasons for love as a survival tool. Humans are dependent on parental help for a large portion of their lifespans compared to other mammals. Love has therefore been seen as a mechanism to promote parental support of children for this extended time period. Furthermore, researchers as early as Charles Darwin identified unique features of human love compared to other mammals and credited love as a major factor for creating social support systems that enabled the development and expansion of the human species.[citation needed] Another factor may be that sexually transmitted diseases can cause, among other effects, permanently reduced fertility, injury to the fetus, and increase complications during childbirth. This would favor monogamous relationships over polygamy.[28]

Adaptive benefit

Interpersonal love between a man and woman provides an evolutionary adaptive benefit since it facilitates mating and sexual reproduction.[29] However, some organisms can reproduce asexually without mating. Understanding the adaptive benefit of interpersonal love depends on understanding the adaptive benefit of sexual reproduction as opposed to asexual reproduction. Richard Michod reviewed evidence that love, and consequently sexual reproduction, provides two major adaptive advantages.[29] First, sexual reproduction facilitates repair of damages in the DNA that is passed from parent to progeny (during meiosis, a key stage of the sexual process). Second, a gene in either parent may contain a harmful mutation, but in the progeny produced by sexual reproduction, expression of a harmful mutation introduced by one parent is likely to be masked by expression of the unaffected homologous gene from the other parent.[29]

Comparison of scientific models

Biological models of love tend to see it as a mammalian[clarification needed] drive, similar to hunger or thirst.[20] Psychology sees love as more of a social and cultural phenomenon. Love is influenced by hormones (such as oxytocin), neurotrophins (such as NGF), and pheromones, and how people think and behave in love is influenced by their conceptions of love. The conventional view in biology is that there are two major drives in love: sexual attraction and attachment. Attachment between adults is presumed to work on the same principles that lead an infant to become attached to its mother. The traditional psychological view sees love as being a combination of companionate love and passionate love. Passionate love is intense longing, and is often accompanied by physiological arousal (shortness of breath, rapid heart rate); companionate love is affection and a feeling of intimacy not accompanied by physiological arousal.

Health

Love plays a role in human well-being and health.[30][31] Engaging in activities associated with love, such as nurturing relationships, has been shown to activate key brain regions responsible for emotion, attention, motivation, and memory. These activities also contribute to the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, leading to stress reduction over time, although the initial stages of love may induce stress.[30] Love's social bonds enhance both physical and mental health, fostering resilience, compassion, and closeness. It boosts immune function and promotes healing, while also encouraging positive motivations and behaviors for individual flourishing and survival.[30] Breakups can evoke a range of emotional states, including distrust, rejection, and anger, leading to trauma and various psychological challenges such as anxiety, social withdrawal, and even love addiction. Individuals may become fixated on past relationships, perpetuating emotional distress akin to addiction.[32] Health benefits grow bigger when married couples are older, this is because the partners play a crucial role in promoting each other's well-being.[33] A loving relationship with God has significant impact on health.[31]

Cultural views

Ancient Greek

Greek distinguishes several different senses in which the word "love" is used. Ancient Greeks identified three main forms of love: friendship and/or platonic desire (philia), sexual and/or romantic desire (eros), and self-emptying or divine love (agape).[18] Modern authors have distinguished further varieties of romantic love.[34]

- Agape (ἀγάπη agápē)

- Agape, often a Christian term, denotes a form of love that stands apart from the conventional understanding of affection. Rooted in theological discourse, agape represents a love that is characterized by its spontaneous nature and its independence from the inherent value of its object. Originating from the Greek term for "love", agape has been examined within theological scholarship, particularly in contrast to eros. In the Christian tradition, agape is often attributed to the love of God for humanity, as well as humanity's reciprocal love for God and for one another, often termed as brotherly love. Agape is considered to be unmerited and unmotivated by any inherent worthiness in its recipient. Instead, it is portrayed as an expression of the nature of God, exemplifying divine love that transcends human comprehension.[18]

- Eros (ἔρως érōs)

- Eros originally referred to a passionate desire, often synonymous with sexual passion, reflecting an egocentric nature. However, its modern interpretation portrays it as both selfish and responsive to the merits of the beloved, thus contingent on reasons. Plato, in his Symposium, argued that sexual desire, fixated on physical beauty, is inadequate and should evolve into an appreciation of the beauty of the soul, culminating in an appreciation of the form of beauty itself.[18] In Greek mythology, Eros symbolizes the state of being in love, extending beyond mere physical sexuality (referred to as "Venus"). Unrestrained Venus can reduce individuals to mere appetite, but when Eros is present, the focus shifts to the beloved, elevating intimacy beyond physical gratification. Eros is depicted as divine yet potentially dangerous, capable of inspiring both altruism and selfishness.[8]

- Philia (φιλία philía)

- Philia originally describing an affectionate regard or friendly feeling, extended to relationships like friendship, family members, business partners, and one's nation. Similar to eros, philia is often seen as responsive to positive attributes in the beloved. This similarity has led scholars to think whether the primary difference between romantic eros and philia lies solely in the sexual dimension of the former. The distinction between the two becomes more complex with attempts from scholars to diminish the importance of the sexual aspect in eros, contributing to a nuanced understanding of these forms of love.[18] Philia was articulated by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle suggests that philia can be motivated by considerations for either one's own benefit or the benefit of the other. Philia often arises from the utility found in the relationship or from admiration for the character or virtues of the other individual. Aristotle further elucidates that the foundation of philia rests on objective grounds; individuals must share similar dispositions, refrain from holding grudges, and embody qualities such as justice, among others.[35]

Ancient Roman

In Latin, friendship was distinctly termed amicitia, while amor encompassed erotic passion, familial attachment, and, albeit less commonly, the affection between friends. Cicero, in his essay On Friendship reflects on the innate human tendency to both love oneself and seek out another with whom to intertwine minds, nearly blending them into a singular entity. This suggests that while friends remain distinct individuals, they also, in some sense, become intertwined, embodying a shared essence.[36]

Lucretius perceives love as a disruptive and irrational force, leading to madness and despair. To him, it is an affliction distorting reality, a primal urge rooted in the biological need for species to propagate. He emphasizes love's futility and self-destructive nature. In contrast, Ovid acknowledges the pleasure of love alongside its risks and complexities. He views love as a game of manipulation and deception, marked by a blend of hedonism and cynicism. Ovid recognizes the transient nature of passion and the inevitable disappointment in romantic relationships.[37]

Chinese

Ren (仁), a concept in Confucianism philosophy, embodies the essence of humanity and virtue. It is regarded as the sum of all virtues within a person, encompassing traits such as selflessness and self-cultivation. Ren emphasizes the cultivation of harmonious relationships within society, starting from the family unit and extending outward. Within Confucianism, these relationships are delineated by five main categories: father-son, older brother-younger brother, husband-wife, older friend-younger friend, and lord-servant. In Confucianism, one displays benevolent love by performing actions such as filial piety from children, kindness from parents, loyalty to the king and so forth.[38]

Central to the concept of Ren is the notion of reciprocity and empathetic understanding. It is often interpreted as akin to love (愛, ài), but sometimes it also considered a stage between ài and ling, characterized by the sincere and open-hearted expression of human feelings. Through genuine love for others, individuals cultivate Ren and foster deeper connections that bridge the gap between the human and the divine. Ren's significance lies in its ability to foster genuine human connection and empathy, laying the foundation for harmonious relationships within society.[39]

Mozi, a Chinese philosopher, articulated a philosophy centered on the principle of universal love. At the core of his teachings lay the belief that genuine harmony and societal well-being could only be achieved through love for others, transcending narrow self-interest. Mozi contended that universal love was not merely an abstract concept but a practical imperative, requiring individuals to actively promote the welfare of all members of society through their actions.[40][41]

In Mozi's philosophical framework, universal love was not only a moral obligation but also a divine principle originating from Heaven itself. He argued that this principle was exemplified through the actions of sage-kings from ancient times, who demonstrated how love could manifest in tangible ways within human interactions. Mozi's advocacy for universal love extended beyond interpersonal relationships; he believed it should guide the selection of rulers and the structuring of society, emphasizing reciprocity and egalitarianism as foundational principles for a harmonious social order.[40][41]

In Taoism, the concept of 慈 (ci) embodies compassion or love, with connotations of tender nurturing akin to a mother's care. It emphasizes the idea that creatures can only thrive through raising and nurturing. Ci serves as the wellspring of compassion or love that transcends preconceived notions of individuals, instead fostering compassion for people as they are. Love, as depicted in the Taoist text, Daodejing, is depicted as open and responsive to each person's unique circumstances. Taoism juxtaposes human beings with the vastness of nature, likening the creation of people to the formation of waves in the ocean. Unlike Confucianism, as portrayed in the Taoist text Zhuangzi, Taoist responses to the loss of a beloved may involve either mourning their death or embracing the loss and finding joy in new creations. Daoist love seeks connections that surpass distinctions and superficial reflections.[42]

Japanese

The Japanese language uses three words to convey the English equivalent of love — ai (愛), koi (恋 or 孤悲) and ren'ai (恋愛). The term ai carries a multiple meanings, encompassing feelings of feelings from superior to inferiors, compassion and empathy towards others and selfless love, originally referred to beauty and was often used in a religious context. Initially synonymous with koi, representing romantic love between a man and a woman, emphasizing its physical expression, ai underwent a transformation during the early Meiji era. It evolved into a euphemistic term for renbo (恋慕) or love attachment, signifying a shift towards a more egalitarian treatment and consideration of others as equals. Prior to Western influence, the term koi generally represented romantic love. Koi describes a longing for a member of the opposite sex and is typically interpreted as selfish and wanting. The term's origins come from the concept of lonely solitude as a result of separation from a loved one. Though modern usage of koi focuses on sexual love and infatuation, the Manyō used the term to cover a wider range of situations, including tenderness, benevolence, and material desire. The fusion of ai and koi gave rise to the modern term ren'ai; its usage more closely resembles that of koi in the form of romantic love.[43][44]

The concept amae (甘え), the dependency and emotional bonds between an infant and its mother—a bond that lays the foundation for the archetypal concept of love. Japanese culture traditionally distinguishes between marriage and love, valuing practical considerations and complementarity within family units.[44]

Indian

In ancient India, there was an understanding of erotics and the art of love. References in the Rigveda suggest the presence of romantic narratives in ancient Indo-Aryan society, evident in dialogues between deities like Yama and Yami, and Pururavas and Urvashi. The Sanskrit language, offered various terms to convey the concept of love, such as kama, sneha, priya, vatsalya, bhakti, priti and prema.[45]

In Indian literature, there are seven stages of love. The first is preska, characterized by the desire to see something pleasant. Next is abhilasa, involving constant thoughts about the beloved. Then comes raga, signifying the mental inclination to be united with the beloved. Following that is shena, which involves favorable activities directed towards the beloved. Prema is the stage where one cannot live without the beloved. Then there is rati, which involves living together with the beloved. Finally, srngara represents the playful interaction with the beloved.[45]

Kama initially representing desire and longing. Later, Vātsyāyana, the author of the Kama Sutra, explored the concept of kama, defining it as the enjoyment of sensory pleasures with conscious awareness. However, there were also teachings cautioning against becoming overly attached to desire, advocating for the pursuit of genuine happiness through transcending desires. The Atharvaveda, presents kama as the tender affection between partners.[45]

Nevertheless, kama is also often associated with insatiable sexual desire intertwined with intense emotions like anger and greed, portraying it as potentially harmful. Over time, kama took on anthropomorphic qualities, evolving into the figure of the Indian Cupid.[45]

Sneha, considered the emotional facet of love, stands in contrast to the intense passion of kama with its calm demeanor. Characterized by moisture and viscosity, the term originally denoted oiliness. It is often compounded with words for family members, reflecting attachment to individuals like mothers, fathers, and sons. Those experiencing sneha tend to exhibit great concern for one another. While traditionally attributed to sensing, the Harshacharita presents a spontaneous perspective, suggesting it lacks a definitive cause. Due to its emotional nature, sneha is transient, emerging without reason and disappearing likewise.[45]

Preman represents a heightened stage in the development of love, characterized by the unbearable feeling of separation from the beloved. Etymologically, it denotes the sense of endearment akin to one's own. Priti, similar to preman, denotes fondness for anything delightful and familiar. It encompasses a general liking for arts, sports, and objects, while also encompassing a human instinct. Priti is built on foundations of trust and fidelity. Friendly relations (priti) may persist between individuals but are not necessarily bound by affection (sneha).[45]

Vatsalya originally signifies the tender affection exhibited by a cow towards her calf, extending to denote the love nurtured by elders or superiors towards the younger or inferior. This love is exemplified in the affection of parents towards their children, a husband's care for his wife, or a ruler's concern for their subjects. Conversely, bhakti denotes the love expressed by the younger towards the seniors, exemplified in a child's devotion to their parents.[45]

Persian

Interpretations of Rumi's poetry and Sufi cosmology by scholars emphasize a divine-centric perspective, focusing on the transcendent nature of love. These interpretations emphasize Rumi's rejection of mortal attachments in favor of a love for the ultimate beloved, seen as embodying absolute beauty and grandeur. Scholars like William Chittick assert that all love stems from the divine, with God being both lover and beloved. Leonard Lewisohn characterizes Rumi's poetry as part of a mystical tradition that celebrates love as pathways to union with the divine, highlighting a transcendent experience.[46]

The children of Adam are limbs of one body

Having been created of one essence.

When the calamity of time afflicts one limb

The other limbs cannot remain at rest.

If you have no sympathy for the troubles of others

You are not worthy to be called by the name of "man".

In Persian mysticism, the concept of creation stems from love, viewed as the fundamental essence from which all beings originate and to which they ultimately return. This notion, influenced by neoplatonism, portrays love as both earthly and transcendent, embodying a universal striving for reunion with the divine. Scholars such as Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob trace this philosophical stance, highlighting its fusion with ancient Persian religious beliefs in figures like Ibn Arabi. According to Islamicists like William Chittick and Leonard Lewisohn, all forms of love find their origin in divine love, with creation serving as a reflection of God's beauty and love. This perspective is evident in the poetry of Hafez and others, where the concept of tajalli, or divine self-manifestation, underscores the profound spiritual significance of love as it pertains to both human relationships and devotion to God.[46]

Religious views

Abrahamic

Judaism

In Hebrew, אהבה (ahavah) signifies the love of Israelites for God and each other. However, the concept hesed offers a deeper understanding of love within Jewish thought and life. It goes beyond mere passion, embodying a character trait that is actively expressed through generosity and grace. Hesed has a dual nature: when attributed to God, it denotes grace or favor, while when practiced by humans, it reflects piety and devotion.[42][page needed]

Hasidim, demonstrate their commitment and love for God through acts of hesed. The Torah serves as a guide, outlining how Israelites should express their love for God, show reverence for nature, and demonstrate compassion toward fellow human beings.[42] The commandment "Love thy neighbor as thyself" from the Torah's, gives emphasis on ethical obligations and impartiality in judgment. It highlights the importance of treating all individuals equally before the law, rejecting favoritism and bribery; deuteronomy further emphasizes impartiality in judgment.[47]

As for love between marital partners, this is deemed an essential ingredient to life: "See life with the wife you love" (Ecclesiastes 9:9). Rabbi David Wolpe writes that "love is not only about the feelings of the lover... It is when one person believes in another person and shows it." He further states that "love... is a feeling that expresses itself in action. What we really feel is reflected in what we do."[48] The biblical book Song of Solomon is considered a romantically phrased metaphor of love between God and his people, but in its plain reading it reads like a love song. The 20th-century rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler is frequently quoted as defining love from the Jewish point of view as "giving without expecting to take".[49]

Christianity

The Christian understanding is that love comes from God, who is himself love (1 John 4:8). The love of man and woman—eros in Greek—and the unselfish love of others (agape), are often contrasted as "descending" and "ascending" love, respectively, but are ultimately the same thing.[50]

There are several Greek words for "love" that are regularly referred to in Christian circles.

- agape

- In the New Testament, agapē is charitable, selfless, altruistic, and unconditional. It is parental love, seen as creating goodness in the world; it is the way God is seen to love humanity, and it is seen as the kind of love that Christians aspire to have for one another.[8]

- phileo

- Also used in the New Testament, phileo is a human response to something that is found to be delightful. Also known as "brotherly love."

Two other words for love in the Greek language, eros (sexual love) and storge (child-to-parent love), were never used in the New Testament.[8]

Christians believe that to love God with all your heart, mind, and strength and love your neighbor as yourself are the two most important things in life (the greatest commandment of the Jewish Torah, according to Jesus; cf. Gospel of Mark 12:28–34). Saint Augustine summarized this when he wrote "Love God, and do as thou wilt."[51]

The Apostle Paul glorified love as the most important virtue of all. Describing love in the famous poetic interpretation in 1 Corinthians, he wrote, "Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, and always perseveres." (1 Corinthians 13:4–7)

The Apostle John wrote, "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him." (John 3:16–17) John also wrote, "Dear friends, let us love one another for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love." (1 John 4:7–8)

Saint Augustine wrote that one must be able to decipher the difference between love and lust. Lust, according to Saint Augustine, is an overindulgence, but to love and be loved is what he has sought for his entire life. He even says, "I was in love with love."[citation needed] Finally, he does fall in love and is loved back, by God. Saint Augustine says the only one who can love you truly and fully is God, because love with a human only allows for flaws such as "jealousy, suspicion, fear, anger, and contention."[52]: III.1 According to Saint Augustine, to love God is "to attain the peace which is yours."[52]: X.27

Augustine regards the duplex commandment of love in Matthew 22 as the heart of Christian faith and the interpretation of the Bible. After the review of Christian doctrine, Augustine treats the problem of love in terms of use and enjoyment until the end of Book I of De Doctrina Christiana (1.22.21–1.40.44).[53]

Christian theologians see God as the source of love, which is mirrored in humans and their own loving relationships. Influential Christian theologian C. S. Lewis wrote a book called The Four Loves. Benedict XVI named his first encyclical God is love. He said that a human being, created in the image of God, who is love, is able to practice love; to give himself to God and others (agape) and by receiving and experiencing God's love in contemplation (eros). This life of love, according to him, is the life of the saints such as Teresa of Calcutta and Mary, the mother of Jesus and is the direction Christians take when they believe that God loves them.[50]

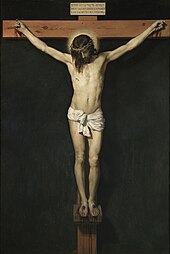

Pope Francis asserts that the "Cross (Jesus crucified) is the greatest meaning of the greatest love,"[54] and in the crucifixion is found everything, all knowledge and the entirety of God's love.[55] Pope Francis taught that "True love is both loving and letting oneself be loved... what is important in love is not our loving, but allowing ourselves to be loved by God."[56] And so, in the analysis of a Catholic theologian, for Pope Francis, "the key to love... is not our activity. It is the activity of the greatest, and the source, of all the powers in the universe: God's."[57]

In Christianity the practical definition of love is summarized by Thomas Aquinas, who defined love as "to will the good of another," or to desire for another to succeed.[12] This is an explanation of the Christian need to love others, including their enemies. Thomas Aquinas explains that Christian love is motivated by the need to see others succeed in life, to be good people.

Regarding love for enemies, Jesus is quoted in the Gospel of Matthew:

You have heard that it was said, "Love your neighbor and hate your enemy." But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.

Tertullian wrote regarding love for enemies: "Our individual, extraordinary, and perfect goodness consists in loving our enemies. To love one's friends is common practice, to love one's enemies only among Christians."[58]

Islam

Love encompasses the Islamic view of life as universal brotherhood that applies to all who hold faith. Among the 99 names of God (Allah) is the name Al-Wadud, or "the Loving One," which is found in Surah 11:90 and 85:14. God is also referenced at the beginning of every chapter in the Qur'an as Ar-Rahman and Ar-Rahim, or the "Most Compassionate" and the "Most Merciful", indicating that nobody is more loving, compassionate, and benevolent than God. The Qur'an refers to God as being "full of loving kindness."

The Qur'an exhorts Muslim believers to treat all people, those who have not persecuted them[clarification needed], with birr or "deep kindness" as stated in Surah 6:8-9. Birr is also used by the Qur'an to describe the love and kindness that children must show to their parents.

Ishq, or divine love, is emphasized by Sufism in the Islamic tradition. Practitioners of Sufism believe that love is a projection of the essence of God into the universe. God desires to recognize beauty, and as if one looks at a mirror to see oneself, God "looks" at himself within the dynamics of nature. Since everything is a reflection of God, the school of Sufism practices seeing the beauty inside the apparently ugly. Sufism is often referred to as the religion of love.[59] God in Sufism is referred to in three main terms—Lover, Loved, and Beloved—with the last of these terms often seen in Sufi poetry. A common viewpoint of Sufism is that through love, humankind can return to its inherent purity and grace. The saints of Sufism are infamous for being "drunk" due to their love of God; hence, the constant reference to wine in Sufi poetry and music.

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í concept of the human soul emphasizes its expression through capacities such as knowledge, love, and will. According to Bahá'í teachings, conscious recognition of one's Creator and a reciprocal love relationship with that Creator form the basis of obedience to religious law. This perspective grounds adherence to law within the spiritual dynamics of each individual's journey, portraying obedience as a conscious choice driven by love rather than as mere compliance with external dictates.[60]

Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, emphasizes the importance of observing God's commandments out of love, describing them as "the lamps of My loving providence" and urging followers to adhere to them for "the love of My beauty." This framing positions love as the motive force for individuals striving to follow divine laws.[60] In Bahá'í understanding, love is considered the fundamental universal law. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Bahá'u'lláh's son and successor, describes love as the "most great law" and the force that binds together the diverse elements of the material world. He further asserts that love is the establisher of true civilization and the source of glory for every race and nation.[60]

From the Bahá'í perspective, God's revelation of laws to humanity is an act of love, and the legitimate reason for their application and adherence lies in their expression of love. This understanding underscores the intimate connection between spiritual principles, individual growth, and the practice of religious law within the Bahá'í Faith.[60]

Dharmic

Buddhism

In Buddhism, love is understood as a selfless, universal quality that serves as the foundation for compassion, joy in others' happiness, and equanimity. Together, these four qualities—loving-kindness (maitrī), compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekṣā)—are known as the brahmavihara. Loving-kindness, the first of the four, fosters goodwill toward all beings and leads naturally to compassion for those who suffer, joy in others' achievements, and, ultimately, to equanimity, a balanced state free from attachment and aversion. This progression helps practitioners to reduce negative tendencies like ill-will, jealousy, and possessiveness, with the ultimate aim of cultivating inner peace and a compassionate view toward all beings, supporting both personal growth and societal harmony.[61]

In Theravada, love and sympathy play key roles in shaping ethical behavior and social actions. Sympathy motivates altruistic acts like teaching and helping others, while loving-kindness is cultivated primarily through meditation, acting as a form of mental liberation. Together, these qualities encourage impartial love and empathy, fostering personal peace and societal harmony, and supporting both individual growth and a more compassionate world.[62]

In Mahayana, love is understood as profound compassion and a commitment to mutual support. This concept is central to the Bodhisattva ideal, where practitioners vow to help all beings reach enlightenment, often delaying their own liberation to support others. Mahayana teachings emphasize selfless love, blurring the boundary between self and others and seeing all beings as interconnected. This love, framed within the Mahayana understanding of reality as ultimately illusory, transcends ego and guides both the practitioner and others toward collective liberation.[63]

In Vajrayana, love is a transformative force that, when disciplined, leads to spiritual enlightenment. Rather than rejecting desire, Vajrayana encourages the refinement of love and other potent energies as pathways to higher consciousness. By controlling and sublimating these energies, often represented through sexual energy as life force (kKundalini), practitioners unite the principles of wisdom and skill. Here, love becomes a symbol and method for ultimate unity, guiding practitioners to enlightenment by transforming personal desire into universal connection.[64]

Hinduism

In Hinduism, kāma is pleasurable, sexual love, personified by the god Kamadeva. For many Hindu schools, it is the third end (Kama) in life. Kamadeva is often pictured holding a bow of sugar cane and an arrow of flowers; he may ride upon a great parrot.[relevant?] He is usually accompanied by his consort Rati and his companion Vasanta, lord of the spring season.[relevant?] Stone images of Kamadeva and Rati can be seen on the door of the Chennakeshava Temple, Belur, in Karnataka, India.[relevant?] Maara is another name for kāma.[citation needed]

In contrast to kāma, prema—or prem refers to "elevated" love. Karuṇā is compassion and mercy, which impels one to help reduce the suffering of others. Bhakti is a Sanskrit term meaning "loving devotion to the divine." A person who practices bhakti is called a bhakta. Hindu writers, theologians, and philosophers have distinguished nine forms of bhakti, which can be found in the Bhagavata Purana and works by Tulsidas. The philosophical work Narada Bhakti Sutra, written by an unknown author (presumed to be Narada), distinguishes eleven forms of love.

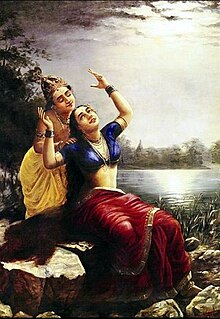

In certain Vaishnava sects within Hinduism, attaining unadulterated, unconditional, and incessant love for the Godhead is considered the foremost goal of life. Gaudiya Vaishnavas, who worship Krishna as the Supreme Personality of Godhead and the cause of all causes, consider Love for Godhead, (Prema), to act in two ways: sambhoga and vipralambha (union and separation)—two opposites.[65]

In the condition of separation, there is an acute yearning for being with the beloved and in the condition of union, there is supreme happiness. Gaudiya Vaishnavas consider that Krishna-prema (love for Godhead) burns away one's material desires, pierces the heart, and washes away everything—one's pride, one's religious rules, and one's shyness. Krishna-prema is considered to make one drown in the ocean of transcendental ecstasy and pleasure. The love of Radha, a cowherd girl, for Krishna is often cited as the supreme example of love for Godhead by Gaudiya Vaishnavas. Radha is considered to be the internal potency of Krishna, and is the supreme lover of Godhead. Her example of love is considered to be beyond the understanding of the material realm, as it surpasses any form of selfish love or lust that is visible in the material world. The reciprocal love between Radha (the supreme lover) and Krishna (God as the Supremely Loved) is the subject of many poetic compositions in India, such as the Gita Govinda of Jayadeva and Hari Bhakti Shuddhodhaya.

In the Bhakti tradition within Hinduism, it is believed that execution of devotional service to God leads to the development of Love for God (taiche bhakti-phale krsne prema upajaya), and as love for God increases in the heart, the more one becomes free from material contamination (krishna-prema asvada haile, bhava nasa paya). Being perfectly in love with God or Krishna makes one perfectly free from material contamination, and this is the ultimate way of salvation or liberation. In this tradition, salvation or liberation is considered inferior to love, and just an incidental by-product. Being absorbed in Love for God is considered to be the perfection of life.[66]

Political views

Free love

The term "free love" has been used[67] to describe a social movement that rejects marriage, which is seen as a form of social bondage. The free love movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It claimed that such issues were the concern of the people involved, and no one else.[68]

Many people in the early 19th century believed that marriage was an important aspect of life to "fulfill earthly human happiness."[69] Middle-class Americans wanted the home to be a place of stability in an uncertain world. This mentality created a vision of strongly defined gender roles, which provoked the advancement of the free love movement as a contrast.[70]

Advocates of free love had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forceful sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.[71] These are also beliefs of feminism.[72]

Philosophical views

Philosophically, love is often categorized into four types: love as a union, robust concern, valuing, and emotion. Love as a union suggests love forms a "we" by merging individual identities, as proposed by thinkers like Roger Scruton and Robert Nozick, who argue this fusion enhances shared care. Critics, however, contend that union threatens individual autonomy, though Nozick and others believe this merging enriches love. Michael Friedman offers a compromise with his federation model, where love unifies yet preserves individual identities.[18]

Love as robust concern defines love as a deep care for the beloved's well-being without creating a union. This view prioritizes concern for the beloved's welfare, but critics argue it misses the interactive and emotional aspects of love. Supporters maintain that love's essence lies in respecting the beloved's autonomy. Monique Wonderly adds that attachment complements this view, making the beloved important for both themselves and the lover.[18]

Love as valuing includes two approaches: appraisal and bestowal of value. J. David Velleman argues that appraisal responds to the inherent dignity in others, making love a unique emotional vulnerability. However, this view struggles to explain love's selectivity and constancy. Peter Singer's bestowal view posits that love creates intrinsic value in the beloved, yet critics question how this explains love's discernment.[18]

Love as an emotion is seen either as an emotion proper or as an emotion complex. Emotion proper treats love as a specific motivational response, but some find this too simplistic. The emotion complex perspective suggests that love is a dynamic, interconnected emotional history shaped by the relationship. Figures like Annette Baier and Neera K. Badhwar highlight emotional interdependence, though critics wonder how this distinguishes love from other relationships and defines its unique narrative.[18]

Literature depictions

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

See also

- Color wheel theory of love – The six love styles created by John Alan Lee

- Finger heart – Hand gesture

- Hand heart – Affectionate hand gesture

- Heart in hand – Symbol of charity

- ILY sign – American Sign Language gesture

- Love at first sight – Falling in long-lasting love with someone on first sight

- Polyamory – Intimacy for multiple partners

- Relationship science – Field dedicated to the scientific study of interpersonal relationship processes

- Romance (love) – Type of love that focuses on feelings

- Self-love – Concept in philosophy and psychology

References

- ^

- "Definition of love in English". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Meaning of love in English". Cambridge English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Karandashev, Victor (2017). Romantic Love in Cultural Contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42683-9. ISBN 978-3-319-42681-5.[page needed]

- Hongladarom, Soraj; Joaquin, Jeremiah Joven, eds. (2021). Love and Friendship Across Cultures. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-33-4834-9. ISBN 978-981-334-833-2. S2CID 243232407.[page needed]

- Treger, Stanislav; Sprecher, Susan; Hatfield, Elaine C. (2014). "Love". Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 3708–3712. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1706. ISBN 978-94-007-0752-8.

Love is a universal human experience.

- ^

- Oxford Illustrated American Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 485.

- "Love Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. 27 December 1987. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- "Love Definition & Meaning". YourDictionary. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Fromm, Erich (1956). The Art of Loving (Original English ed.). Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-095828-2.

- ^ Abbas, Azhar (11 April 2011). "Just Love". Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Callerame, Emmanuelle (3 February 2022). "An Exploration of Love in Art History". Artsper Magazine. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ Fisher, Helen (2004). Why We Love: the nature and chemistry of romantic love. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0805069136.

- ^

- Catron, Adrian (5 December 2014). "What Is Love? A Philosophy of Life". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "φιλία". A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Bhagavad Gita. Penguin Classics. Translated by Mascaró, Juan. Penguin. 2003. ISBN 978-0-14-044918-1.

- ^ a b c d Nygren, Anders Theodor Samuel (1936). Agape and Eros.

- ^ Kay, Paul; Kempton, Willett (March 1984). "What is the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis?". American Anthropologist. New Series. 86 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1525/aa.1984.86.1.02a00050. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ^ "Ancient Love Poetry". TrueOpenLove. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. VIII.

- ^ a b Aquinas, Thomas (1485). Summa Theologiae. New Advent. I–II, Q26, Art.4.

- ^ Kirsh, Marvin Eli (2013). "Philosophy, Science and Value". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2250431. ISSN 1556-5068. SSRN 2250431.

- ^ Leibniz, Gottfried (1673). "Confessio philosophi". Wikisource edition. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1995). Discourses. Myrtle Beach: Sheriar Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-880619-09-4.

- ^ Griffith, Jeremy (2011). "What is love?". The Book of Real Answers to Everything!. ISBN 978-1-74129-007-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Love" entry in The Devil's Dictionary at Dict.org

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Helm, Bennett (2021), "Love", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 15 April 2024

- ^ "Paraphilia". DiscoveryHealth. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ a b Lewis, Thomas; Amini, F.; Lannon, R. (2000). A General Theory of Love. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-70922-7.

- ^ a b Fisher, Helen E.; Aron, Arthur; Mashek, Debra; Li, Haifang; Brown, Lucy L. (2002). "Defining the Brain Systems of Lust, Romantic Attraction, and Attachment" (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 31 (5): 413–419. doi:10.1023/A:1019888024255. PMID 12238608. S2CID 14808862. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ a b Holt World History: The Human Legacy. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. 1 January 2008. ISBN 978-0-03-093780-4.

- ^ Emanuele, E.; Polliti, P.; Bianchi, M.; Minoretti, P.; Bertona, M.; Geroldi, D. (2005). "Raised plasma nerve growth factor levels associated with early-stage romantic love". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31 (3): 288–294. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.09.002. PMID 16289361. S2CID 18497668. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- ^ Sternberg, R.J. (1986). "A triangular theory of love". Psychological Review. 93 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.93.2.119.

- ^

- Rubin, Zick (1970). "Measurement of Romantic Love". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 16 (2): 265–273. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.3207. doi:10.1037/h0029841. PMID 5479131.

- Rubin, Zick (1973). Liking and Loving: an invitation to social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 978-0030830037.

- ^ Berscheid, Ellen; Walster, Elaine H. (1969). Interpersonal Attraction. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-201-00560-8. LCCN 69-17443.

- ^ Peck, Scott (1978). The Road Less Traveled. Simon & Schuster. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-671-25067-6.

- ^ Campbell, Lorne; Ellis, Bruce J. (2005). "Commitment, Love, and Mate Retention". In Buss, David M. (ed.). The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ a b c Michod, Richard E. (1989). "What's love got to do with it? The solution to one of evolution's greatest riddles". The Sciences: 22–27. doi:10.1002/j.2326-1951.1989.tb02156.x.

- ^ a b c Esch, Tobias; Stefano, George B. (June 2005). "Love promotes health". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 26 (3): 264–267. ISSN 0172-780X. PMID 15990734.

- ^ a b Hemberg, Jessica; Eriksson, Katie; Nystrom, Lisbet (2017). "Love as the Original Source of Strength for Life and Health". International Journal of Caring Sciences. 10 (2). S2CID 45264075.

- ^ Timmreck, Thomas C. (April 1990). "Overcoming the Loss of a Love: Preventing Love Addiction and Promoting Positive Emotional Health". Psychological Reports. 66 (2): 515–528. doi:10.2466/pr0.1990.66.2.515. ISSN 0033-2941. PMID 2190254.

- ^ Rauer, Amy J.; Sabey, Allen; Jensen, Jakob F. (August 2014). "Growing old together: Compassionate love and health in older adulthood". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 31 (5): 677–696. doi:10.1177/0265407513503596. ISSN 0265-4075.

- ^ Stendhal, in his book On Love ("De l'amour"; Paris, 1822), distinguished carnal love, passionate love, a kind of uncommitted love that he called "taste-love", and love of vanity. Denis de Rougemont in his book Love in the Western World traced the story of passionate love (l'amour-passion) from its courtly to its romantic forms. Benjamin Péret, in the introduction to his Anthology of Sublime Love (Paris, 1956), further identified "sublime love", a state of realized idealisation perhaps equatable with the romantic form of passionate love.

- ^ "Philosophy of Love | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Konstan, David (19 July 2018). In the Orbit of Love. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190887872.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-088787-2.

- ^ Singer, Irving (1965). "Love in Ovid and Lucretius". The Hudson Review. 18 (4): 537–559. doi:10.2307/3849704. ISSN 0018-702X. JSTOR 3849704.

- ^ Havens, Timothy (2013). "Confucianism as Humanism" (PDF). CLA Journal.

- ^ Wang, Huaiyu; 王懷聿 (2012). ""Ren" and "Gantong": Openness of Heart and the Root of Confucianism". Philosophy East and West. 62 (4): 463–504. doi:10.1353/pew.2012.0067. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 41684476.

- ^ a b Wang, Yuxi (Candice) (28 April 2016). "Mozi: Universal Love and Human Agency". 2016 Claremont Colleges Library Undergraduate Research Award.

- ^ a b Cotesta, Vittorio (1 January 2021), The Heavens and the Earth: Graeco-Roman, Ancient Chinese, and Mediaeval Islamic Images of the World, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-46472-8, retrieved 25 April 2024

- ^ a b c Martin, Adrienne M., ed. (21 December 2018). The Routledge Handbook of Love in Philosophy. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315645209. ISBN 978-1-315-64520-9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Ryang, Sonia (2006). Love in Modern Japan: Its Estrangement from Self, Sex and Society. Routledge. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-135-98863-0. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b Palmer, Gary B.; Occhi, Debra J. (15 December 1999). Languages of Sentiment: Cultural constructions of emotional substrates. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-9995-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hara, Minoru (2007). "Words for love in Sanskrit". Rivista degli studi orientali. 80 (1/4): 81–106. JSTOR 41913379.

- ^ a b Vali-Zadeh, Mahdieh (2 June 2022). "Agency of the Self and the Uncertain Nature of the Beloved in Persian Love Mysticism: Earthly, Ethereal, Masculine, or Feminine?". Teosofi: Jurnal Tasawuf Dan Pemikiran Islam. 12 (1): 22–42. doi:10.15642/teosofi.2022.12.1.22-42. ISSN 2442-871X.

- ^ Goodman, Lenn Evan. Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, 13.

- ^ Wolpe, David (16 February 2016). "We Are Defining Love the Wrong Way". Time. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Dessler, Eliyahu. "Kuntres ha-Chesed". Michtav me-Eliyahu (in Hebrew). Vol. 1.

- ^ a b Pope Benedict XVI. "papal encyclical, Deus Caritas Est". Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo, "Homily 7 on the First Epistle of John", Homilies on First John, translated by Browne, H., New Advent, 8

- ^ a b Augustine of Hippo. Confessions.

- ^ Woo, B. Hoon (2013). "Augustine's Hermeneutics and Homiletics in De doctrina christiana". Journal of Christian Philosophy. 17: 97–117. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ a b McLellan, Justin. "'Do you cry?' pope asks 800,000 young people at WYD; so does Jesus, he says". Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Brockhaus, Hannah (22 April 2020). "Pope Francis: The entirety of God's love is found in the crucifix". Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Pope Francis (18 January 2015). "Meeting with the young people in the sports field of Santo Tomas University". w2.vatican.va. Manila. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Nidoy, Raul (13 February 2015). "The key to love according to Pope Francis". Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Tertulliam, Ad Scapulam, vol. I

- ^ Lewisohn, Leonard (2014). Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–180.

- ^ a b c d Danesh, Roshan (1 June 2014). "Some Reflections on the Concept of Law in the Bahá'í Faith". The Journal of Bahá'í Studies. 24 (1–2): 27–46. doi:10.31581/jbs-24.1-2.3(2014). ISSN 2563-755X.

- ^ Piyapanyawong, Anchalee (29 March 2018). "An Analysis of Love Development in Buddhism". วารสารวิทยบริการ มหาวิทยาลัยสงขลานครินทร์ | Academic Services Journal, Prince of Songkla University. 29 (1): 174–187. ISSN 2351-0420.

- ^ Hallisey, Charles (August 1982). "Love and Sympathy in Theravāda Buddhism. By Harvey B. Aronson. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1980. viii, 127 pp. Notes, Bibliography, Glossary, Indexes. Rs 45". The Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (4): 859–860. doi:10.2307/2055485. ISSN 1752-0401. JSTOR 2055485.

- ^ Noss, John B. (1952). "Mutual Love in Mahayana Buddhism". Journal of Bible and Religion. 20 (2): 84–89. ISSN 0885-2758. JSTOR 1458923.

- ^ Yogi, P. G. (著) (November 1998). "An Analysis of Tantrayana (Vajrayana)". Bulletin of Tibetology. 34 (3): 16–38.

- ^ Gour Govinda Swami. "The Wonderful Characteristic of Krishna Prema". Facebook. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami (29 November 1966). "Perfectly in Krishna Love". Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Hand-book of the Oneida Community. 1867. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Claims to have coined the term around 1850, and laments that its use was appropriated by socialists to attack marriage, an institution that they felt protected women and children from abandonment.[page needed]

- ^ McElroy, Wendy (1996). "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism". Libertarian Enterprise. 19: 1.

- ^ "Free love - Connexipedia article". www.connexions.org. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Spurlock, John C. (1988). Free Love, Marriage, and Middle-Class Radicalism in America. New York: New York University Press.

- ^ Passet, Joanne E. (2003). Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Laurie, Timothy; Stark, Hannah (2017), "Love's Lessons: Intimacy, Pedagogy and Political Community", Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, 22 (4): 69–79, doi:10.1080/0969725x.2017.1406048, S2CID 149182610, archived from the original on 21 February 2023, retrieved 3 January 2018

Sources

- Chadwick, Henry (1998). Saint Augustine Confessions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283372-3.

- Fisher, Helen (2004). Why We Love: the Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6913-6.

- Giles, James (1994). "A theory of love and sexual desire". Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 24 (4): 339–357. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1994.tb00259.x.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (2009). Works of Love. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics. ISBN 978-0-06-171327-9.

- Oord, Thomas Jay (2010). Defining Love: A Philosophical, Scientific, and Theological Engagement. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos. ISBN 978-1-58743-257-6.

- Singer, Irving (1966). The Nature of Love. Vol. (in three volumes) (v.1 reprinted and later volumes from The University of Chicago Press, 1984 ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-0-226-76094-0.

- Sternberg, R.J. (1986). "A triangular theory of love". Psychological Review. 93 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.119.

- Sternberg, R.J. (1987). "Liking versus loving: A comparative evaluation of theories". Psychological Bulletin. 102 (3): 331–345. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.331.

- Tennov, Dorothy (1979). Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-6134-1.

- Wood Samuel E., Ellen Wood and Denise Boyd (2005). The World of Psychology (5th ed.). Pearson Education. pp. 402–403. ISBN 978-0-205-35868-7.

Further reading

- Bayer, A, ed. (2008). Art and love in Renaissance Italy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

External links

- History of Love, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy