Lezgins

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 473,722 385,240[1] | |

| 180,300 [2][3] | |

| 16,000 | |

| 4,349 | |

| 4,300 | |

| 3,481 | |

| 2,603 | |

| 2,000 | |

| 404 | |

| 280 | |

| 121 | |

| 82 | |

| 74 | |

| 44 | |

| Languages | |

| Lezgian | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam, Shi'a minority[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tabasarans, Aghuls, Rutuls, Budukhs, Kryts, Tsakhurs, Archi, Shahdagh, Udi, and other Northeast Caucasian peoples | |

The Lezgians (Lezgian: лезгияр, лекьер, lezgiyar, Russian: лезгины, lezginy; also called Lezgins, Lezgi, Lezgis, Lezgs, Lezgin) are a Lezgic ethnic group native predominantly in Lezgia located in southern Dagestan and northeastern Azerbaijan and who speak the Lezgian language.

Еthnonym

The origin of the ethnonym Lezgin requires further research. Nevertheless, most researchers attribute the derivation of Lezgi to be from the ancient Legi and early medieval Lakzi.

Modern-day Lezgins speak Northeast Caucasian languages that have been spoken in the region before the introduction of Indo-European languages. They are closely related, both culturally and linguistically, to the Aghuls of southern Dagestan and, somewhat more distantly, to the Tsakhurs, Rutuls, and Tabasarans (the northern neighbors of the Lezgins). Also related, albeit more distantly, are the numerically small Jek, Kryts, Shahdagh, Budukh, and Khinalug peoples of northern Azerbaijan. These groups, together with the Lezgins, form the Samur branch of the indigenous Lezgic peoples.

Lezgins are believed to descend partly from people who inhabited the region of southern Dagestan in the Bronze Age. However, there is some DNA evidence of significant admixture during the last 4,000 years with a Central Asian population, as shown by genetic links to populations throughout Europe and Asia, with notable similarities to the Burusho of Pakistan.[7]

Prior to the Russian Revolution, the Lezgins did not have a common self-designation as an ethnic group. They referred to themselves by village, region, religion, clan, or free society. Before the revolution, the Lezgins were called "Kyurintsy", "Akhtintsy", or "Lezgintsy" by the Russians. The ethnonym "Lezgin" itself is quite problematic. Prior to the Soviet period, the term "Lezgin" was used in different contexts. At times, it referred only to the people known today as Lezgins. At others, it referred variously to all of the peoples of southern Daghestan (Lezgin, Aghul, Rutul, Tabasaran, and Tsakhur); all of the peoples of southern Daghestan and northern Azerbaijan (Kryts Jek, Khinalug, Budukh, Shahdagh); all Nakh-Daghestani peoples; or all of the indigenous Muslim peoples of the Northeast Caucasian peoples (Caucasian Avars, Dargwa, Laks, Chechens, and Ingush). In reading pre-Revolutionary works, one must be aware of these different possible meanings and the scope of the ethnonym "Lezgin".

History

In the 4th century BC, the numerous tribes speaking Lezgic languages united in a union of 26 tribes, formed in the Eastern Caucasus state of Caucasian Albania, which itself was incorporated in the Persian Achaemenid Empire in 513 BCE.[8][9] Under the influence of initially Persian but also Parthian rule Caucasian Albania was divided into several areas - Lakzi, Shirvan, etc.

The Lezgic speaking tribes participated in the battle of Gaugamela under the Persian banner against the invading Alexander the Great.[8]

Under Parthian rule, Iranian political and cultural influence increased in the whole region of their Caucasian Albanian province, therefore including where the Lezgic speaking tribes lived.[10] Whatever the sporadic suzerainty of Rome of the region due to their wars with the Parthians, the country was now a part—together with Iberia (East Georgia) and (Caucasian) Albania, where other Arsacid branches reigned—of a pan-Arsacid family federation.[10] Culturally, the predominance of Hellenism, as under the Artaxiads, was now followed by again a predominance of "Iranianism", and, symptomatically, instead of Greek, as before, Parthian became the language of the educated of the region.[10] An incursion in this era was made by the Alans who between 134 and 136 attacked regions including where Lezgic tribes lived, but Vologases persuaded them to withdraw, probably by paying them.

In 252–253, rule over the Lezgic tribes changed from Parthian to Sassanid Persian. Caucasian Albania became a vassal state,[11] now of the Sassanids, but retained its monarchy; the Albanian king had no real power and most civil, religious, and military authority lay with the Sassanid marzban (military governor) of the territory.[8]

The Roman Empire obtained control over some of the southernmost Lezgin regions for a few years around 300 AD, but then the Sassanid Persians regained control and subsequently dominated the area for centuries until the Arab invasions.

Although Lezgins were first introduced to Islam perhaps as early as the 8th century, the Lezgins remained primarily animist until the 15th century, when Muslim influence became stronger, with Persian traders coming in from the south, and the Golden Horde increasingly pressing from the north. In the 16th century, the Persian Safavids started consolidating their control over Dagestan for many centuries onwards, with the Ottoman Turks who occasionally briefly occupied the area as well, and both also helped to consolidate Islam in the region. By the 19th century, the Lezgins had all been converted to Islam, and they have since then been very devout in their faith.

The Lezgins did not form their own country. While under Persian rule from the 16th century till the early 19th century, some were part of the Kuba Khanate in what is now Azerbaijan, while others were under control of the Derbent Khanate, both under full Persian suzerainty. The Lak Kazi Kumukh Khanate controlled a part of the Lezgins for a time in the 18th century after the disintegration of the Safavid Empire. A notable Lezgin from the Safavid Iranian era was Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani, who served as the vizier of the Safavid king (shah) Sultan Husayn (r. 1694–1722) from 1716 to 1720.

At the beginning of the 18th century in eastern Transcaucasia there were anti-Persian uprisings by the Lezgins and other peoples of Dagestan and Azerbaijan following the same decline of the Safavids. Under the leadership of Haji Dawood Myushkyurskogo (r. 1721–1728) in the vast territory of Shirvan they created the Lezgin State Khanate with its capital in Shemakha.

In the first half of the 18th century, Persia was able to restore its full authority throughout the entire Caucasus under Nader Shah. After the death of Nader, he created the state into divided several smaller khanates. The main part of Lezgins united in "free society" (Magalim) (Akhty para, Alti-para, Kure, Dokuz-para); Lezghians in Azerbaijani khanate in the Kuba and Dagestan Lezgins - in the Derbent Khanate. In 1812 most of the Dagestani Lezgins became part of the educated in southern Dagestan, a Russian protectorate Kyurinskoe Khanate, which was transformed in 1864 into Kyurinsky District, and the rest - in the Samur district, most of the Azerbaijani Lezgins - in the Kuban district of Baku province.

From 1813 onwards, the Russians took over following the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) but permanently after the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), forcing Persia to cede all of its territories in the North Caucasus and South Caucasus, thus making all Lezgins fall under nominal Russian rule.[12][12] The Russian administration subsequently created the Kiurin Khanate, later to become the Kiurin district. Many Lezgins in Dagestan, however, participated in the Great Caucasian War that started roughly during the same time the Russo-Persian Wars of the 19th century were happening, and fought against the Russians alongside the Avar Imam Shamil, who for 25 years (1834–1859) defied Russian rule. It was not until after his defeat in 1859 that the Russians consolidated their rule over Dagestan and the Lezgins.

In 1930, Sheikh Mohammed Effendi Shtulskim organized an uprising against Soviet rule, which was suppressed after several months. In the 20th century, attempts were made to create a republic of Lezgistan (independent or as an autonomous region)

Some Lezgins were deported to Central Asia in the 1940s by Stalin's regime.

Historical concept

While ancient Greek historians, including Herodotus, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder, referred to Legoi people who inhabited Caucasian Albania, Arab historians of the 9th and 10th centuries mention the kingdom of Lakz in present-day southern Dagestan.[13] Al Masoudi referred to inhabitants of this area as Lakzams (Lezgins),[14] who defended Shirvan against invaders from the north.[15] The Lezgin ethnic group probably resulted from a merger of the Akhty, the Alty and Dokus Para federations, and some clans from among the Rutuls.

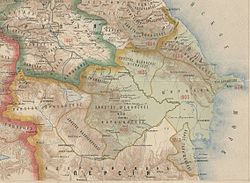

Geography

The Lezgins inhabit a compact territory that straddles the border area of southern Daghestan and northern Azerbaijan. It lies, for the most part, in the southeastern portion of Daghestan in (Akhtynsky District, Dokuzparinsky District, Suleyman-Stalsky District, Kurakhsky District, Magaramkentsky District, Khivsky District, Derbentsky District and Rutulsky District) and contiguous northeastern Azerbaijan (in Kuba, Qusar, Qakh, Khachmaz, Oguz, Qabala, Nukha, and Ismailli districts).

The Lezgin territories are divided into two physiographic zones: a region of high, rugged mountains and the piedmont (foothills). Most of the Lezgin territory is in the mountainous zone, where a number of peaks (like Baba Dagh) reach over 3,500 meters in elevation. There are deep and isolated canyons and gorges formed by the tributaries of the Samur and Gulgeri Chai rivers. In the mountainous zones the summers are very hot and dry, with drought conditions a constant threat. There are few trees in this region aside from those in the deep canyons and along the streams themselves. Drought-resistant shrubs and weeds dominate the natural flora. The winters here are frequently windy and brutally cold. In this zone the Lezgins engaged primarily in animal husbandry (mostly sheep and goats) and in craft industries.

In the extreme east of the Lezgin territory, where the mountains give way to the narrow coastal plain of the Caspian Sea, and to the far south, in Azerbaijan, are the foothills. This region has relatively mild, very dry winters and hot, dry summers. Trees are few here also. In this region animal husbandry and artisanry were supplemented by some agriculture (along the alluvial deposits near the rivers).

Language

The Lezgian language belongs to the Lezgic branch of the Northeast Caucasian language family (with Aghul, Rutul, Tsakhur, Tabasaran, Budukh, Khinalug, Jek, Khaput, Kryts, and Udi).

The Lezgian language has three closely related (mutually intelligible) dialects: Kurin (also referred to as Gunei or Kurakh), Akhti, and Kuba. The Kurin dialect is the most widespread of the three and is spoken throughout most of the Lezgin territories in Daghestan, including the town of Kurakh, which, historically, was the most important cultural, political, and economic center in the Lezgin territory in Daghestan and is the former seat of the khanate of Kurin. The Akhti dialect is spoken in southeastern Daghestan. The Kuba dialect, the most Turkicized of the three, is widespread among the Lezgins of northern Azerbaijan (named for the town of Kuba, the cultural and economical focus of the region).

Modern times

Prior to the Russian Revolution, "Lezgin" was a term applied to all ethnic groups inhabiting the present-day Russian Republic of Dagestan.[16]

In the 19th century, the term was used more broadly for all ethnic groups speaking non-Nakh Northeast Caucasian languages, including Caucasian Avars, Laks, and many others (although the Vainakh peoples, who were Northeast Caucasian language speakers were referred to as "Circassians").

The area known as Lezgistan was divided between the Tsarist districts of Derbent and Baku in 1860, a division which continues into the 21st century.

Today, the Lezgins are predominantly Sunni Muslims, with a Shia minority living in Miskindja village in Dagestan.

The Lezgins resisted Russification by refusing to participate in programs to relocate them from the highlands and into lowland towns and collective farms. Thus, the majority of the Lezgins still maintain a traditional lifestyle.

Glasnost and Perestroika policies in the late 1980s, early 1990s, economic collapse, and the fall of the Soviet Union exacerbated nationalistic tensions and unleashed centrifugal ethnic forces. The Lezgins, as so many other ethnic groups, became more strident in their demands for independence from Moscow and for self-determination.

For the most part, the relations between the various ethnic groups of Dagestan are remarkably less competitive than those of the titular nationalities in the other North Caucasian republics. This may change if nationalism, as expressed in the concept of the national state, gains more currency among the larger national groups, like Lezgins or Dargins.

Lezgins live mainly in Azerbaijan and in the Russian Federation (Dagestan). The total population is believed to be around 700,000, with 474,000 living in Russian Federation.

In the Republic of Azerbaijan, the government census counts 180,300.[3] However, Lezgin national organizations mention 600,000 to 900,000, the disparity being that many Lezgins claim Azeri nationality to escape job and education discrimination in Azerbaijan.[5] Despite the assimilationist policy of the Azeri government, the Lezgin population is undoubtedly greater than it appears.[17]

Lezgins also live in Central Asia.[18]

Situation in Azerbaijan

In 1992 a Lezgin organization named Sadval was established to promote Lezgin rights. Sadval campaigned for the redrawing of the Russian–Azerbaijani border to allow for the creation of a single Lezgin state encompassing areas in Russia and Azerbaijan where Lezgins were compactly settled. In Azerbaijan a more moderate organization called Samur was formed, advocating more cultural autonomy for Lezgins in Azerbaijan.

Lezgins traditionally suffered from unemployment and a shortage of land. Resentments were fuelled in 1992 by the resettlement of 105,000 Azeri refugees from the Karabakh conflict on Lezgin lands and by the forced conscription of Lezgins to fight in the conflict. This contributed to an increase in tensions between the Lezgin community and the Azeri government over issues of land, employment, language and the absence of internal autonomy. A major consequence of the outbreak of the war in Chechnya in 1994 was the closure of the border between Russia and Azerbaijan: as a result the Lezgins were for the first time in their history separated by an international border restricting their movement.

The high tide of Lezgin mobilization in Azerbaijan appeared to have passed towards the end of the 1990s. Sadval was banned by the Azerbaijani authorities after official allegations that it was involved in a bombing of the Baku underground. The end of the Karabakh war, and Lezgin resistance to forced conscription, deprived the movement of a key issue on which to mobilize. In 1998 Sadval split into ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ wings, following which it appeared to lose much of its popularity on both sides of the Russian–Azerbaijani border.

However, Azerbaijani–Lezgin relations continued to be complicated by claims that Islamic fundamentalism enjoyed disproportionate popularity among Lezgins. In July 2000 Azerbaijani security forces arrested members of Lezgin and Avar ethnicity of a group named the Warriors of Islam, which allegedly was planning an insurgency against the Azerbaijani state.

Lezgins expressed concern over underrepresentation in the Azerbaijani Parliament (Milli Meclis) after a shift away from proportional representation in the parliamentary elections of November 2005. Lezgins had been represented by two members of parliament in the previous parliament, but are now represented by only one.

Lezgin is taught as a foreign language in areas where many Lezgins are settled, but teaching resources are scarce. Lezgin textbooks come from Russia and are not adapted to local conditions. Although Lezgin newspapers are available, Lezgins have also expressed concern over the disappearance of their rich oral tradition. The only Lezgin television broadcasting available in Azerbaijan is that received over the border from Russia.

In March 2006 Azerbaijani media reported that Sadval had formed an 'underground' terrorist unit carrying out operations in Dagestan. Security forces across the border in Dagestan in Russia, responded sceptically to these reports.

Situation in Dagestan

According to reports Lezgins in Dagestan suffer disproportionately from unemployment, with unemployment rates in Lezgin-populated areas of southern Dagestan twice the republican average of 32 per cent. This may be one contributory factor to renewed calls from within the Sadval movement in January 2006 for a redrawing of the Russian-Azerbaijani border to incorporate Lezgin-populated areas of southern Dagestan within Azerbaijan.

In March 1999 another organization, the Federal Lezgin National Cultural Autonomy, was established as an extraterritorial movement advocating cultural autonomy for Lezgins.

See also

- Gotfrid Hasanov

- Nazim Huseynov

- Nader's Dagestan campaign

- Suleyman Kerimov

- Suleyman Stalsky

- Lezginka

- Lezgian language

- Lezgistan

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Northeast Caucasian people

References

- ^ "Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации согласно переписи аселения 2010 года". gks.ru. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ^ http://www.ethnologue.com/language/lez

- ^ a b The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Population by ethnic groups

- ^ "The Role of Ethnic Minorities in Border Regions: Forms of their composition, problems of development and political rights". Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ a b Minahan, p. 1084. "Lezgin national organizations estimate the actual Lezgin population in Azerbaijan at between 600,000 and 900,000, much higher than the official estimates. The disparity arises from the number of ethnic Lezgins registered as ethnic Azeris during the soviet period and continue to claim Azeri nationality to escape job and education discrimination in Azerbaijan."

- ^ Ethnologue report for Lezgi

- ^ New York Times, 2014, "Genetic Mixing" (February 13; interactive). (Access: October 15 2014).

- ^ a b c Chaumont, M. L. Albania. "Encyclopaedia Iranica. Cite error: The named reference "Chaumont" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Bruno Jacobs, "ACHAEMENID RULE IN Caucasus" in Encyclopædia Iranica. January 9, 2006. Excerpt: "Achaemenid rule in the Caucasus region was established, at the latest, in the course of the Scythian campaign of Darius I in 513–512 BCE. The Persian domination of the cis-Caucasian area (the northern side of the range) was brief, and archeological findings indicate that the Great Caucasus formed the northern border of the empire during most, if not all, of the Achaemenid period after Darius"

- ^ a b c Toumanoff, Cyril. The Arsacids. Encyclopædia Iranica. excerpt:"Whatever the sporadic suzerainty of Rome, the country was now a part—together with Iberia (East Georgia) and (Caucasian) Albania, where other Arsacid branched reigned—of a pan-Arsacid family federation. Culturally, the predominance of Hellenism, as under the Artaxiads, was now followed by a predominance of "Iranianism," and, symptomatically, instead of Greek, as before, Parthian became the language of the educated"

- ^ Yarshater, p. 141.

- ^ a b "Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ..." Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin (1993). A grammar of Lezgian. Walter de Gruyter. p. 17. ISBN 3-11-013735-6.

- ^ Yakut, IV, 364. According to al-Masoudi (Murudzh, II, 5)

- ^ VFMinorsky. History of Shirvan. M. 1963

- ^ Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 438. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.

- ^ Robert Bruce Ware, Enver Kisriew, E.F. Kisriew, "Dagestan: Russian hegemony and Islamic resistance in the North Caucasus",M.E. Sharpe, 2009 "given the assimilationist policies of the Azeri authories, the Lezgin population of that state is undoubtedly greater than it appears" [1]

- ^ Yo'av Karny,"Highlanders: A Journey to the Caucasus in Quest of Memory",Macmillan, 2001. pp 112:"The last 1989 all Soviet census recorded 204,400 Lezgins in Daghestan and 171,395 Lezgins in Azerbaijan. Both figures reflected a relative, almost identical decline (5 percent) in Lezgin numbers in both "homelands". Roughly 65,000 Lezgins were counted in other parts of the Soviet Union, mostly Russia, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan"

Bibliography

- Minahan, J. (2002) Encyclopaedia of stateless nations: L-R, Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313321115.

- Yarshater, E. (1983) The Cambridge history of Iran, Volume One, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.