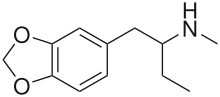

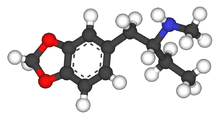

MBDB

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

| |

Chemical structure | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Methylbenzodioxolylbutanamine; N-Methyl-1,3-benzodioxolylbutanamine; MBDB; 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methyl-butanphenamine; MDMB |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 207.27 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 156 °C (313 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

1,3-Benzodioxolyl-N-methylbutanamine (N-methyl-1,3-benzodioxolylbutanamine, MBDB, 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methyl-α-ethylphenylethylamine) is an entactogen of the phenethylamine chemical class. It is known by the street names Eden and Methyl-J.[1] MBDB is a closely related chemical analogue of MDMA, with the only difference between the two molecules being an ethyl group instead of a methyl group attached to the alpha carbon. It has IC50 values of 784 nM against 5-HT, 7825 nM against dopamine, and 1233 nM against norepinephrine.[citation needed] Its metabolism has been described in scientific literature.[2]

MBDB was first synthesized by pharmacologist and medicinal chemist David E. Nichols[citation needed] and later tested by Alexander Shulgin and described in his book, PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. MBDB's dosage, according to PiHKAL, is 180–210 mg; the proper dosage relative to body mass seems unknown. Its duration is 4–6 hours, with noticeable after-effects lasting for 1–3 hours.

MBDB was initially developed as a non-psychedelic entactogen. It has lower effects on the dopamine system in comparison to other entactogens such as MDMA.[citation needed] MBDB causes many mild, MDMA-like effects, such as lowering of social barriers and inhibitions, pronounced sense of empathy and compassion, mood lift, and mild euphoria are all present.[citation needed] MBDB tends to produce less euphoria, psychedelia, and stimulation in comparison.[citation needed]

Legal Status

Unlike MDMA, MBDB is not internationally scheduled under the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The thirty-second meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (September 2000) evaluated MBDB and recommended against scheduling.[3] From the WHO Expert Committee assessment of MBDB:

- Although MBDB is both structurally and pharmacologically similar to MDMA, the limited available data indicate that its stimulant and euphoriant effects are less pronounced than those of MDMA. There have been no reports of adverse or toxic effects of MBDB in humans. Law enforcement data on illicit trafficking of MBDB in Europe suggest that its availability and abuse may now be declining after reaching a peak during the latter half of the 1990s. For these reasons, the Committee did not consider the abuse liability of MBDB would constitute a significant risk to public health, thereby warranting its placement under international control. Scheduling of MBDB was therefore not recommended.

Australia

MBDB is considered a Schedule 9 Prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[4] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[4]

Russia

MBDB is included into Schedule 1 of the Controlled Substances Act. [1]

Sweden

Sveriges riksdags health ministry Statens folkhälsoinstitut classified MBDB as "health hazard" under the act Lagen om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor (translated Act on the Prohibition of Certain Goods Dangerous to Health) as of Feb 25, 1999, in their regulation SFS 1999:58 listed as "2-metylamino-1-(3,4-metylendioxifenyl)-butan (MBDB)", making it illegal to sell or possess.[5]

See also

- Ethylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (EBDB; Ethyl-J)

- Methylbenzodioxolylpentanamine (MBDP; Methyl-K)

- UWA-101

References

- ^ "Erowid MBDB Vault". www.erowid.org.

- ^ Foon Yin Lai; Claudio Erratico; Juliet Kinyua; Jochen F. Mueller; Adrian Covaci; Alexander L.N. van Nuijs (October 2015). "Liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for screening in vitro drug metabolites in humans: investigation on seven phenethylamine-based designer drugs". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 114: 355–375. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.06.016. PMID 26112925.

- ^ WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Thirty-second Report, Technical Report Series 903 (2001)

- ^ a b Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- ^ http://www.notisum.se/rnp/sls/sfs/19990058.pdf