Superman

| Superman | |

|---|---|

| File:Superman.jpg | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| First appearance | Action Comics #1 (June 1938) |

| Created by | Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Kal-El, adopted as Clark Joseph Kent |

| Place of origin | Krypton |

| Team affiliations | The Daily Planet Justice League Legion of Super-Heroes Team Superman |

| Notable aliases | Gangbuster, Jordan Elliot, Nightwing, Supernova, Superboy, The Red and Blue Blur, Superman Prime, Commander El |

| Abilities | Superhuman strength, speed, stamina, durability, senses, intelligence, regeneration, and longevity; super breath, heat vision, x-ray vision and flight |

Superman is a fictional character, a comic book superhero appearing in publications by DC Comics, widely considered to be an American cultural icon.[1][2][3][4] Created by American writer Jerry Siegel and Canadian-born artist Joe Shuster in 1932 while both were living in Cleveland, Ohio, and sold to Detective Comics, Inc. in 1938, the character first appeared in Action Comics #1 (June 1938) and subsequently appeared in various radio serials, television programs, films, newspaper strips, and video games. With the success of his adventures, Superman helped to create the superhero genre and establish its primacy within the American comic book.[1] The character's appearance is distinctive and iconic: a blue, red and yellow costume, complete with cape, with a stylized "S" shield on his chest.[5][6][7] This shield is now typically used across media to symbolize the character.[8]

The original story of Superman relates that he was born Kal-El on the planet Krypton, before being rocketed to Earth as an infant by his scientist father Jor-El, moments before Krypton's destruction. Discovered and adopted by a Kansas farmer and his wife, the child is raised as Clark Kent and imbued with a strong moral compass. Very early he started to display superhuman abilities, which upon reaching maturity he resolved to use for the benefit of humanity.

While referred to less than flatteringly as "the big blue Boy Scout" by some of his fellow superheroes,[9] Superman is hailed as "The Man of Steel", "The Man of Tomorrow", and "The Last Son of Krypton" by the general public within the comics. As Clark Kent, Superman lives among humans as a "mild-mannered reporter" for the Metropolis newspaper Daily Planet (Daily Star in the earliest stories). There he works alongside reporter Lois Lane, with whom he is romantically linked. This relationship has been consummated by marriage on numerous occasions across various media, and this union is now firmly established within mainstream comics' continuity.

DC Comics/Warner Bros. slowly expanded the character's supporting cast, powers, and trappings throughout the years. Superman's backstory was altered to allow for adventures as Superboy, and other survivors of Krypton were created, including Supergirl and Krypto the Superdog. In addition, Superman has been licensed and adapted into a variety of media, from radio to television and film, perhaps most notably portrayed by Christopher Reeve in both Richard Donner's Superman: The Movie in 1978, and the sequel Superman II in 1981, which garnered critical praise and became Warner Bros.'s most successful feature films of their time. However, the next two sequels, Superman III and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, did not perform as well at the box office. The motion picture Superman Returns was released in 2006, which although relatively unsuccessful within the United States, returned a performance at the international box office which exceeded expectations.[10] In the seven decades since Superman's debut, the character has been revamped and updated several times.

A significant overhaul occurred in 1986, when John Byrne revamped and "retconned" the character, reducing Superman's powers and erasing several characters from the canon, in a move that attracted media attention. Press coverage was again garnered by DC Comics in the 1990s with The Death of Superman, a storyline which saw the character killed and later restored to life.

Superman has fascinated scholars, with cultural theorists, commentators, and critics alike exploring the character's impact and role in the United States and the rest of the world. Umberto Eco discussed the mythic qualities of the character in the early 1960s, and Larry Niven has pondered the implications of a sexual relationship the character might enjoy with Lois Lane.[11] The character's ownership has often been the subject of dispute, with Siegel and Shuster twice suing for the return of legal ownership. The copyright is again currently in dispute, with changes in copyright law allowing Siegel's wife and daughter to claim a share of the copyright, a move DC parent company Warner Bros. disputes.

Publication history

Creation and conception

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster first created a bald telepathic villain bent on dominating the entire world. He appeared in the short story "The Reign of the Super-Man" from Science Fiction #3, a science fiction fanzine that Siegel published in 1933.[12] Siegel re-wrote the character in 1933 as a hero, bearing little or no resemblance to his villainous namesake, modeling the hero on Douglas Fairbanks Sr. and his bespectacled alter ego, Clark Kent, on Harold Lloyd.[13][14] Siegel and Shuster then began a six-year quest to find a publisher. Titling it The Superman, Siegel and Shuster offered it to Consolidated Book Publishing, who had published a 48-page black-and-white comic book entitled Detective Dan: Secret Operative No. 48. Although the duo received an encouraging letter, Consolidated never again published comic books. Shuster took this to heart and burned all pages of the story, the cover surviving only because Siegel rescued it from the fire. Siegel and Shuster each compared this character to Slam Bradley, an adventurer the pair had created for Detective Comics #1 (May 1939).[15]

Siegel contacted other artists to collaborate on the strip, according to Gerard Jones feeling that "Superman was going nowhere with Joe".[16] Tony Strobl, Mel Graff and Russell Keaton were all contacted as potential collaborators by Siegel.[16] Artwork produced by Keaton based on Siegel's treatment shows the concept evolving. Superman is now sent back in time as a baby by the last man on Earth, where he is found and raised by Sam and Molly Kent.[17] However Keaton did not pursue the collaboration, and soon Siegel and Shuster were back working together on the character.[16]

The pair re-envisioned the character, who became more of a hero in the mythic tradition, inspired by such characters as Samson and Hercules,[18] who would right the wrongs of Siegel and Shuster's times, fighting for social justice and against tyranny. It was at this stage the costume was introduced, Siegel later recalling that they created a "kind of costume and let's give him a big S on his chest, and a cape, make him as colorful as we can and as distinctive as we can."[5] The design was based in part on the costumes worn by characters in outer space settings published in pulp magazines, as well as comic strips such as Flash Gordon,[19] and also partly suggested by the traditional circus strong-man outfit.[5][20] However, the cape has been noted as being markedly different from the Victorian tradition. Gary Engle described it as without "precedent in popular culture" in Superman at Fifty: The Persistence of a Legend.[21] The circus performer's shorts-over-tights outfit was soon established as the basis for many future superhero outfits. This third version of the character was given extraordinary abilities, although this time of a physical nature as opposed to the mental abilities of the villainous Superman.[5]

The locale and the hero's civilian names were inspired by the movies, Shuster said in 1983. "Jerry created all the names. We were great movie fans, and were inspired a lot by the actors and actresses we saw. As for Clark Kent, he combined the names of Clark Gable and Kent Taylor. And Metropolis, the city in which Superman operated, came from the Fritz Lang movie [Metropolis, 1927], which we both loved".[22]

Although they were by now selling material to comic book publishers, notably Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson's National Allied Publishing, the pair decided to feature this character in a comic strip format, rather than in the longer comic book story format that was establishing itself at this time. They offered it to both Max Gaines, who passed, and to United Feature Syndicate, who expressed interest initially but finally rejected the strip in a letter dated February 18, 1937. However, in what historian Les Daniels describes as "an incredibly convoluted turn of events", Max Gaines ended up positioning the strip as the lead feature in Wheeler-Nicholson's new publication, Action Comics. Vin Sullivan, editor of the new book, wrote to the pair requesting that the comic strips be refashioned to suit the comic book format, requesting "eight panels a page". However Siegel and Shuster ignored this, utilizing their own experience and ideas to create page layouts, with Siegel also identifying the image used for the cover of Action Comics #1 (June 1938), Superman's first appearance.[23]

Siegel may have been inspired to create the Superman character due to the death of his father. Mitchell Siegel was an immigrant who owned a clothing store on New York's Lower East Side. He died during a robbery attempt in 1932, a year before Superman was created. Although Siegel never mentioned the death of his father in interviews, both Gerard Jones and Brad Meltzer believe it must have affected him. "It had to have an effect," says Jones. "There's a connection there: the loss of a dad as a source for Superman." Meltzer states: "Your father dies in a robbery, and you invent a bulletproof man who becomes the world's greatest hero. I'm sorry, but there's a story there."[24]

Publication

Superman's first appearance was in Action Comics #1, in 1938. In 1939, a self-titled series was launched. The first issue mainly reprinted adventures published in Action Comics, but despite this the book achieved greater sales.[25] 1939 also saw the publication of New York World's Fair Comics, which by summer of 1942 became World's Finest Comics. With issue #7 of All Star Comics, Superman made the first of a number of infrequent appearances, on this occasion appearing in cameo to establish his honorary membership of the Justice Society of America.[26]

Initially Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster would provide the story and art for all the strips published. However, Shuster's eyesight began to deteriorate, and the increasing appearances of the character saw an increase in the workload. This led Shuster to establish a studio to assist in the production of the art,[25] although he insisted on drawing the face of every Superman the studio produced. Outside the studio, Jack Burnley began supplying covers and stories in 1940,[27] and in 1941, artist Fred Ray began contributing a stream of Superman covers, some of which, such as that of Superman #14 (Feb. 1942), became iconic and much-reproduced. Wayne Boring, initially employed in Shuster's studio, began working for DC in his own right in 1942 providing pages for both Superman and Action Comics.[28] Al Plastino was hired initially to copy Wayne Boring but was eventually allowed to create his own style and became one of the most prolific Superman artists during the Gold and Silver Ages of comics.[29]

The scripting duties also became shared. In late 1939 a new editorial team assumed control of the character's adventures. Whitney Ellsworth, Mort Weisinger and Jack Schiff were brought in following Vin Sullivan's departure. This new editorial team brought in Edmond Hamilton, Manly Wade Wellman, and Alfred Bester, established writers of science fiction.[30]

By 1943, Jerry Siegel was drafted into the army in a special celebration, and his duties there saw high contributions drop. Don Cameron and Alvin Schwartz joined the writing team, Schwartz teaming up with Wayne Boring to work on the Superman comic strip which had been launched by Siegel and Shuster in 1939.[28]

In 1945, Superboy made his debut in More Fun Comics #101. The character moved to Adventure Comics in 1946, and his own title, Superboy, launched in 1949. The 1950s saw the launching of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen (1954) and Superman's Girlfriend Lois Lane (1958). By 1974 these titles had merged into Superman Family, although the series was cancelled in 1982. DC Comics Presents was a series published from 1978 to 1986 featuring team-ups between Superman and a wide variety of other characters of the DC Universe.

In 1986, a decision was taken to restructure the universe the Superman character inhabited with other DC characters in the mini-series Crisis on Infinite Earths. This saw the publication of "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow", a two part story written by Alan Moore, with art by Curt Swan, George Pérez and Kurt Schaffenberger.[31] The story was published in Superman #423 and Action Comics #583, and presented what Les Daniels notes as "the sense of loss the fans might have experienced if this had really been the last Superman tale."[32]

Superman was relaunched by writer & artist John Byrne, initially in the limited series The Man of Steel (1986). 1986 also saw the cancellation of World's Finest Comics, and the Superman title renamed Adventures of Superman. A second volume of Superman was launched in 1987, running until cancellation in 2006. This cancellation saw Adventures of Superman revert to the Superman title. Superman: The Man of Steel was launched in 1991, running until 2003, whilst the quarterly book Superman: The Man of Tomorrow ran from 1995 to 1999. In 2003 Superman/Batman launched, as well as the Superman: Birthright limited series, with All Star Superman launched in 2005 and Superman Confidential in 2006 (this title was cancelled in 2008). He also appeared in the TV animated series based comic book tie-ins Superman Adventures (1996–2002), Justice League Adventures, Justice League Unlimited (canceled in 2008) and The Legion of Super-Heroes In The 31st Century (canceled in 2008).

Current ongoing publications that feature Superman on a regular basis are Superman, Action Comics, Superman/Batman and Justice League of America. The character often appears as a guest star in other series and is usually a pivotal figure in DC crossover events.

Influences

An influence on early Superman stories is the context of the Great Depression. The left-leaning perspective of creators Shuster and Siegel is reflected in early storylines. Superman took on the role of social activist, fighting crooked businessmen and politicians and demolishing run-down tenements.[33] This is seen by comics scholar Roger Sabin as a reflection of "the liberal idealism of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal", with Shuster and Siegel initially portraying Superman as champion to a variety of social causes.[34] In later Superman radio programs the character continued to take on such issues, tackling a version of the KKK in a 1946 broadcast.[35][36] Siegel and Shuster's status as children of Jewish immigrants is also thought to have influenced their work. Timothy Aaron Pevey has argued that they crafted "an immigrant figure whose desire was to fit into American culture as an American", something which Pevey feels taps into an important aspect of American identity.[37]

Siegel himself noted that the mythic heroes in the traditions of many cultures bore an influence on the character, including Hercules and Samson.[5] The character has also been seen by Scott Bukatman to be "a worthy successor to Lindberg ... (and) also ... like Babe Ruth", and is also representative of the United States dedication to "progress and the 'new'" through his "invulnerable body ... on which history cannot be inscribed."[38] Further, given that Siegel and Shuster were noted fans of pulp science fiction,[12] it has been suggested that another influence may have been Hugo Danner. Danner was the main character of the 1930 novel Gladiator by Philip Wylie, and is possessed of the same powers of the early Superman.[39]

Comics creator and historian Jim Steranko has cited the pulp hero Doc Savage as another likely source of inspiration, noting similarities between Shuster's initial art and contemporary advertisements for Doc Savage: "Initially, Superman was a variation of pulp heavyweight Doc Savage".[40] Steranko argued that the pulps played a major part in shaping the initial concept: "Siegel's Superman concept embodied and amalgamated three separate and distinct themes: the visitor from another planet, the superhuman being and the dual identity. He composed the Superman charisma by exploiting all three elements, and all three contributed equally to the eventual success of the strip. His inspiration, of course, came from the science fiction pulps",[40] identifying another pulp likely to have influenced the pair as being "John W. Campbell's Aarn Munro stories about a descendant of earthmen raised on the planet Jupiter who, because of the planet's dense gravity, is a mental and physical superman on Earth."[40]

Because Siegel and Shuster were both Jewish, some religious commentators and pop-culture scholars such as Rabbi Simcha Weinstein and British novelist Howard Jacobson suggest that Superman's creation was partly influenced by Moses,[41][42] and other Jewish elements. Superman's Kryptonian name, "Kal-El", resembles the Hebrew words קל-אל, which can be taken to mean "voice of God".[43][44]. The suffix "el", meaning "(of) God"[45] is also found in the name of angels (e.g. Gabriel, Ariel), who are flying humanoid agents of good with superhuman powers. Jewish legends of the Golem have been cited as worthy of comparison,[46] a Golem being a mythical being created to protect and serve the persecuted Jews of 16th century Prague and later revived in popular culture in reference to their suffering at the hands of the Nazis in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s. Superman is often seen as being an analogy for Jesus, being a saviour of humanity.[34][42][46][47]

Whilst the term Superman was initially coined by Friedrich Nietzsche, it is unclear how influential Nietzsche and his ideals were to Siegel and Shuster.[42] Les Daniels has speculated that "Siegel picked up the term from other science fiction writers who had casually employed it", further noting that "his concept is remembered by hundreds of millions who may barely know who Nietzsche is."[5] Others argue that Siegel and Shuster "could not have been unaware of an idea that would dominate Hitler's National Socialism. The concept was certainly well discussed."[48] Yet Jacobson and others point out that in many ways Superman and the Übermensch are polar opposites.[41] Nietzsche envisioned the Übermensch as a man who had transcended the limitations of society, religion, and conventional morality while still being fundamentally human. Superman, although an alien gifted with incredible powers, chooses to honor human moral codes and social mores. Nietzsche envisioned the perfect man as being beyond moral codes; Siegel and Shuster envisioned the perfect man as holding himself to a higher standard of adherence to them.[49]

Siegel and Shuster have themselves discussed a number of influences that impacted upon the character. Both were avid readers, and their mutual love of science fiction helped to drive their friendship. Siegel cited John Carter stories as an influence: "Carter was able to leap great distances because the planet Mars was smaller that the planet Earth; and he had great strength. I visualized the planet Krypton as a huge planet, much larger than Earth".[22] The pair were also avid collectors of comic strips in their youth, cutting them from the newspaper, with Winsor McKay's Little Nemo firing their imagination with its sense of fantasy.[50] Shuster has remarked on the artists which played an important part in the development of his own style, whilst also noting a larger influence: "Alex Raymond and Burne Hogarth were my idols — also Milt Caniff, Hal Foster, and Roy Crane. But the movies were the greatest influence on our imagination: especially the films of Douglas Fairbanks Senior."[51] Fairbanks' role as Robin Hood was certainly an inspiration, as Shuster admitted to basing Superman's stance upon scenes from the movie.[52] The movies also influenced the storytelling and page layouts,[53] whilst the city of Metropolis was named in honor of the Fritz Lang motion picture of the same title.[22]

Copyright issues

As part of the deal which saw Superman published in Action Comics, Siegel and Shuster sold the rights to the company in return for $130 and a contract to supply the publisher with material.[54][55] The Saturday Evening Post reported in 1940 that the pair was each being paid $75,000 a year, a fraction of National Comics Publications' millions in Superman profits.[56] Siegel and Shuster renegotiated their deal, but bad blood lingered and in 1947 Siegel and Shuster sued for their 1938 contract to be made void and the re-establishment of their ownership of the intellectual property rights to Superman. The pair also sued National in the same year over the rights to Superboy, which they claimed was a separate creation that National had published without authorization. National immediately fired them and took their byline off the stories, prompting a legal battle that ended in 1948, when a New York court ruled that the 1938 contract should be upheld. However, a ruling from Justice J. Addison Young awarded them the rights to Superboy. A month after the Superboy judgment the two sides agreed on a settlement. National paid Siegel and Shuster $94,000 for the rights to Superboy. The pair also acknowledged in writing the company's ownership of Superman, attesting that they held rights for "all other forms of reproduction and presentation, whether now in existence or that may hereafter be created",[57] but DC refused to re-hire them.[58]

In 1973 Siegel and Shuster again launched a suit claiming ownership of Superman, this time basing the claim on the Copyright Act of 1909 which saw copyright granted for 28 years but allowed for a renewal of an extra 28 years. Their argument was that they had granted DC the copyright for only 28 years. The pair again lost this battle, both in a district court ruling of October 18, 1973 and an appeal court ruling of December 5, 1974.[59]

In 1975 after news reports of their pauper-like existences, Warner Communications gave Siegel and Shuster lifetime pensions of $20,000 per year and health care benefits. Jay Emmett, then executive vice president of Warner Bros., was quoted in the New York Times as stating, "There is no legal obligation, but I sure feel there is a moral obligation on our part."[56] Heidi MacDonald, writing for Publisher's Weekly, noted that in addition to this pension "Warner agreed that Siegel and Shuster would henceforth be credited as creators of Superman on all comics, TV shows and films".[55]

The year after this settlement, 1976, saw the copyright term extended again, this time for another 19 years to a total of 75 years. However, this time a clause was inserted into the extension to allow authors to reclaim their work, reflecting the arguments Siegel and Shuster had made in 1973. The new act came into power in 1978 and allowed a reclamation window in a period based on the previous copyright term of 56 years. This meant the copyright on Superman could be reclaimed between 1994 to 1999, based on the initial publication date of 1938. Jerry Siegel having died in January 1996, his wife and daughter filed a copyright termination notice in 1999. Although Joe Shuster died in July 1992, no termination was filed at this time by his estate.[60]

1998 saw copyright extended again, with the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. This time the copyright term was extended to 95 years, with a further window for reclamation introduced. In January 2004 Mark Peary, nephew and legal heir to Joe Shuster's estate, filed notice of his intent to reclaim Shuster's half of the copyright, the termination effective in 2013.[60] The status of Siegel's share of the copyright is now the subject of a legal battle. Warner Bros. and the Siegels entered into discussions on how to resolve the issues raised by the termination notice, but these discussions were set aside by the Siegels and in October 2004 they filed suit alleging copyright infringement on the part of Warner Bros. Warner Bros. counter sued, alleging the termination notice contains defects amongst other arguments.[61][62] On March 26, 2008, Judge Larson of the United States District Court for the Central District of California ruled that Siegel's estate was entitled to claim a share in the United States copyright. The ruling does not affect the International rights, which Time Warner holds on the character through DC. Issues regarding the amount of monies owed Siegel's estate and whether the claim the estate has extends to derivative works such as movie versions will be settled at trial, although any compensation would only be owed from works published since 1999. Time Warner offered no statement on the ruling, but do have the right to challenge it.[63][64] The case is currently[update] scheduled to be heard in a California federal court in May, 2008.[65]

A similar termination of copyright notice filed in 2002 by Siegel's wife and daughter concerning the Superboy character was ruled in their favor on March 23, 2006.[66] However, on July 27, 2007, the same court issued a ruling [67] reversing the March 23, 2006 ruling. This ruling is currently subject to a legal challenge from Time Warner, with the case as yet[update] unresolved.[63]

A July 9, 2009 verdict on the case denied a claim by Siegel's family that it was owed licensing fees. U.S. District Court judge Stephen G. Larson said Warner Bros. and DC Comics have fulfilled their obligations to the Siegels under a profit-sharing agreement for the 2006 movie Superman Returns and the CW series Smallville. However the court also ruled that if Warner Bros. does not start a new Superman film by 2011, the family will have the right to sue to recover damages.[68]

Comic book character

Superman, given the serial nature of comic publishing and the length of the character's existence, has evolved as a character as his adventures have increased.[69] The details of Superman's origin, relationships and abilities changed significantly during the course of the character's publication, from what is considered the Golden Age of Comic Books through the Modern Age. The powers and villains were developed through the 1940s, with Superman developing the ability to fly, and costumed villains introduced from 1941.[70] The character was shown as learning of the existence of Krypton in 1949. The concept itself had originally been established to the reader in 1939, in the Superman comic strip.[71]

The 1960s saw the introduction of a second Superman. DC had established a multiverse within the fictional universe its characters shared. This allowed characters published in the 1940s to exist alongside updated counterparts published in the 1960s. This was explained to the reader through the notion that the two groups of characters inhabited parallel Earths. The second Superman was introduced to explain to the reader Superman's membership of both the 1940s superhero team the Justice Society of America and the 1960s superhero team the Justice League of America.[72]

The 1980s saw radical revisions of the character. DC decided to remove the multiverse in a bid to simplify its comics line. This led to the rewriting of the back story of the characters DC published, Superman included. John Byrne rewrote Superman, removing many established conventions and characters from continuity, including Superboy and Supergirl. Byrne also re-established Superman's adoptive parents, The Kents, as characters.[73] In the previous continuity the characters had been written as having died early in Superman's life (about the time of Clark Kent's graduation from high school).

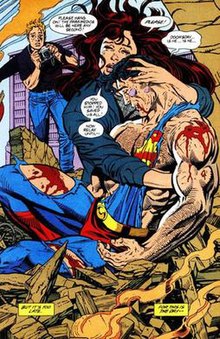

The 1990s saw Superman killed by the villain Doomsday,[74] although the character was soon resurrected.[75] Superman also marries Lois Lane in 1996. His origin is again revisited in 2004.[76] In 2006 Superman is stripped of his powers,[77] although these are restored within a fictional year.[78]

Personality

In the original Siegel and Shuster stories, Superman's personality is rough and aggressive. The character was seen stepping in to stop wife beaters, profiteers, a lynch mob and gangsters, with rather rough edges and a looser moral code than audiences may be used to today.[33] Later writers have softened the character, and instilled a sense of idealism and moral code of conduct. Although not as cold-blooded as the early Batman, the Superman featured in the comics of the 1930s is unconcerned about the harm his strength may cause, tossing villainous characters in such a manner that fatalities would presumably occur, although these were seldom shown explicitly on the page. This came to an end late in 1940, when new editor Whitney Ellsworth instituted a code of conduct for his characters to follow, banning Superman from ever killing.[71] This change would even be reflected in the stories themselves, in which it would occasionally be pointed out in the narrative or dialogue that Superman had vowed never to take human life – and that if he ever did so, he would hang up his cape and retire.

Today, Superman adheres to a strict moral code, often attributed to the Midwestern values with which he was raised. His commitment to operating within the law has been an example to many other heroes but has stirred resentment among others, who refer to him as the "big blue boy scout." Superman can be rather rigid in this trait, causing tensions in super hero community, notably with Wonder Woman (one of his closest friends) after she killed Maxwell Lord.[79]

Having lost his homeworld of Krypton, Superman is very protective of Earth, and especially of Clark Kent’s family and friends. This same loss, combined with the pressure of using his powers responsibly, has caused Superman to feel lonely on Earth, despite his many friends, his wife and his parents. Previous encounters with people he thought to be fellow Kryptonians, Power Girl[80] (who is, in fact from the Krypton of the Earth-Two universe) and Mon-El,[81] have led to disappointment. The arrival of Supergirl, who has been confirmed to be not only from Krypton, but also is his cousin, has relieved this loneliness somewhat.[82]

In Superman/Batman #3 (December 2003), Batman observes, "It is a remarkable dichotomy. In many ways, Clark is the most human of us all. Then...he shoots fire from the skies, and it is difficult not to think of him as a god. And how fortunate we all are that it does not occur to him."[83] Later, as Infinite Crisis began, Batman admonished him for identifying with humanity too much and failing to provide the strong leadership that superhumans need.[84]

As established in Superman: Birthright, Superman is a strict vegetarian.

Other versions

Both the multiverse established by the publishers in the 1960s and the Elseworlds line of comics established in 1989 have allowed writers to introduce variations on Superman. These have included differences in the nationality, race and morality of the character. Alongside such re-imaginings, a number of characters have assumed the title of Superman, especially in the wake of "The Death of Superman" storyline, where four newly introduced characters are seen to claim the mantle.[85] In addition to these, the Bizarro character created in 1958 is a weird, imperfect duplicate of Superman.[86] Other members of Superman's family of characters have borne the Super- prefix, including Supergirl, Superdog and Superwoman. Outside comics published by DC, the notoriety of the Superman or "Übermensch" archetype makes the character a popular figure to be represented through an analogue in entirely unrelated continuities. For example, Roy Thomas based rival publisher Marvel Comics' Hyperion character on Superman.[87][88][89][90]

Powers and abilities

As an influential archetype of the superhero genre, Superman possesses extraordinary powers, with the character traditionally described as "faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, and able to leap tall buildings in a single bound", a phrase coined by Jay Morton and first used in the Superman radio serials and Max Fleischer animated shorts of the 1940s[91] as well as the TV series of the 1950s. For most of his existence, Superman's famous arsenal of powers has included flight, super-strength, invulnerability to non-magical attacks, super-speed, vision powers (including x-ray, heat-emitting, telescopic, infra-red, and microscopic vision), super-hearing, and super-breath, which enables him to blow out air at freezing temperatures, as well as exert the propulsive force of high-speed winds.[92]

As originally conceived and presented in his early stories, Superman's powers were relatively limited, consisting of superhuman strength that allowed him to lift a car over his head, run at amazing speeds and leap one-eighth of a mile, as well as incredibly tough skin that could be pierced by nothing less than an exploding artillery shell.[92] Siegel and Shuster compared his strength and leaping abilities to an ant and a grasshopper.[93] When making the cartoons, the Fleischer Brothers found it difficult to keep animating him leaping and requested to DC to change his ability to flying. (This was an especially convenient conceit for short films, which would have otherwise had to waste precious running time moving earthbound Clark Kent from place to place.)[94] Writers gradually increased his powers to larger extents during the Silver Age, in which Superman could fly to other worlds and galaxies and even across universes with relative ease.[92] He would often fly across the solar system to stop meteors from hitting the Earth, or sometimes just to clear his head. Writers found it increasingly difficult to write Superman stories in which the character was believably challenged,[95] so DC made a series of attempts to rein the character in. The most significant attempt, John Byrne's 1986 rewrite, established several hard limits on his abilities: He barely survives a nuclear blast, and his space flights are limited by how long he can hold his breath.[96] Superman's power levels have again increased since then, with Superman currently possessing enough strength to hurl mountains, withstand nuclear blasts with ease, fly into the sun unharmed, and survive in the vacuum of outer space without oxygen.

The source of Superman's powers has changed subtly over the course of his history. It was originally stated that Superman's abilities derived from his Kryptonian heritage, which made him eons more evolved than humans.[71] This was soon amended, with the source for the powers now based upon the establishment of Krypton's gravity as having been stronger than that of the Earth. This situation mirrors that of Edgar Rice Burroughs' John Carter. As Superman's powers increased, the implication that all Kryptonians had possessed the same abilities became problematic for writers, making it doubtful that a race of such beings could have been wiped out by something as trifling as an exploding planet. In part to counter this, the Superman writers established that Kryptonians, whose native star Rao had been red, only possessed superpowers under the light of a yellow sun.[97] More recent stories have attempted to find a balance between the two explanations.

Superman is most vulnerable to green Kryptonite, mineral debris from Krypton transformed into radioactive material by the forces that destroyed the planet. Exposure to green Kryptonite radiation nullifies Superman's powers and immobilizes him with pain and nausea; prolonged exposure will eventually kill him. The only mineral on Earth that can protect him from Kryptonite is lead, which blocks the radiation. Lead is also the only known substance that Superman cannot see through with his x-ray vision. Kryptonite was first introduced to the public in 1943 as a plot device to allow the radio serial voice actor, Bud Collyer, to take some time off.[69] Although green Kryptonite is the most commonly seen form, writers have introduced other forms over the years: such as red, gold, blue, white, and black, each with its own effect.[98]

Supporting cast

Clark Kent, Superman's secret identity, was based partly on Harold Lloyd and named after Clark Gable and Kent Taylor.[13][14] Creators have discussed the idea of whether Superman pretends to be Clark Kent or vice versa, and at differing times in the publication either approach has been adopted.[99][100] Although typically a newspaper reporter, during the 1970s the character left the Daily Planet for a time to work for television,[100] whilst the 1980s revamp by John Byrne saw the character become somewhat more aggressive.[96] This aggressiveness has since faded with subsequent creators restoring the mild mannerisms traditional to the character.

Superman's large cast of supporting characters includes Lois Lane, perhaps the character most commonly associated with Superman, being portrayed at different times as his colleague, competitor, love interest and/or wife. Other main supporting characters include Daily Planet coworkers such as photographer Jimmy Olsen and editor Perry White, Clark Kent's adoptive parents Jonathan and Martha Kent, childhood sweetheart Lana Lang and best friend Pete Ross, and former college love interest Lori Lemaris (a mermaid). Stories making reference to the possibility of Superman siring children have been featured both in and out of mainstream continuity.

Incarnations of Supergirl, Krypto the Superdog, and Superboy have also been major characters in the mythos, as well as the Justice League of America (of which Superman is usually a member). A feature shared by several supporting characters is alliterative names, especially with the initials "LL", including Lex Luthor, Lois Lane, Linda Lee, Lana Lang, Lori Lemaris and Lucy Lane,[101] alliteration being common in early comics.

Team-ups with fellow comics icon Batman are common, inspiring many stories over the years. When paired, they are often referred to as the "World's Finest" in a nod to the name of the comic book series that features many team-up stories. In 2003, DC began to publish a new series featuring the two characters titled Superman/Batman.

Superman also has a rogues gallery of enemies, including his most well-known nemesis, Lex Luthor, who has been envisioned over the years in various forms as both a rogue scientific genius with a personal vendetta against Superman, or a powerful but corrupt CEO of a conglomerate called LexCorp who thinks Superman is somehow hindering human progress by his heroic efforts.[102] In the 2000s, he even becomes President of the United States,[103] and has been depicted occasionally as a former childhood friend of Clark Kent. The alien android (in most incarnations) known as Brainiac is considered by Richard George to be the second most effective enemy of Superman.[104] The enemy that accomplished the most, by actually killing Superman, is the raging monster Doomsday. Darkseid, one of the most powerful beings in the DC Universe, is also a formidable nemesis in most post-Crisis comics. Other important enemies who have featured in various incarnations of the character, from comic books to film and television include the fifth-dimensional imp Mister Mxyzptlk, the reverse Superman known as Bizarro and the Kryptonian criminal General Zod, among many others.

Cultural impact

Superman has come to be seen as both an American cultural icon[105][106] and the first comic book superhero. His adventures and popularity have established the character as an inspiring force within the public eye, with the character serving as inspiration for musicians, comedians and writers alike. Kryptonite, Brainiac and Bizarro have become synonymous in popular vernacular with Achilles' heel, extreme intelligence[107] and reversed logic[108] respectively. Similarly, the phrase "I'm not Superman" or alternatively "you're not Superman" is an idiom used to suggest a lack of invincibility.[109][110][111]

Inspiring a market

The character's initial success led to similar characters being created.[112][113] Batman was the first to follow, Bob Kane commenting to Vin Sullivan that given the "kind of money (Siegel and Shuster were earning) you'll have one on Monday".[114] Victor Fox, an accountant for DC, also noticed the revenue such comics generated, and commissioned Will Eisner to create a deliberately similar character to Superman. Wonder Man was published in May 1939, and although DC successfully sued, claiming plagiarism,[115] Fox had decided to cease publishing the character. Fox later had more success with the Blue Beetle. Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel, launched in 1940, was Superman's main rival for popularity throughout the 1940s, and was again the subject of a lawsuit, which Fawcett eventually settled in 1953, a settlement which involved the cessation of the publication of the character's adventures.[116] Superhero comics are now established as the dominant genre in American comic book publishing,[117] with many thousands of characters in the tradition having been created in the years since Superman's creation.[118]

Merchandising

Superman became popular very quickly, with an additional title, Superman Quarterly rapidly added. In 1940 the character was represented in the annual Macy's parade for the first time.[119] In fact Superman had become popular to the extent that in 1942, with sales of the character's three titles standing at a combined total of over 1.5 million, Time was reporting that "the Navy Department (had) ruled that Superman comic books should be included among essential supplies destined for the Marine garrison at Midway Islands."[120] The character was soon licensed by companies keen to cash in on this success through merchandising. The earliest paraphernalia appeared in 1939, a button proclaiming membership in the Supermen of America club. By 1940 the amount of merchandise available increased dramatically, with jigsaw puzzles, paper dolls, bubble gum and trading cards available, as well as wooden or metal figures. The popularity of such merchandise increased when Superman was licensed to appear in other media, and Les Daniels has written that this represents "the start of the process that media moguls of later decades would describe as 'synergy.'"[121] By the release of Superman Returns, Warner Bros. had arranged a cross promotion with Burger King,[122] and licensed many other products for sale.

Superman's appeal to licensees rests upon the character's continuing popularity, cross market appeal and the status of the "S" shield, the stylized magenta and gold "S" emblem Superman wears on his chest, as a fashion symbol.[123][124]

The "S" shield by itself is often used in media to symbolize the Superman character. It has been incorporated into the opening and/or closing credits of several films and TV series.

In other media

The character of Superman has appeared in various media aside from comic books. This is in some part seen to be owing to the character's cited standing as an American cultural icon,[125] with the concept's continued popularity also being taken into consideration,[126] but is also seen in part as due to good marketing initially.[121] The character has been developed as a vehicle for serials on radio, television and film, as well as feature length motion pictures, and computer and video games have also been developed featuring the character on multiple occasions.

The first adaptation of Superman was as a daily newspaper comic strip, launching on January 16, 1939. The strip ran until May 1966, and significantly, Siegel and Shuster used the first strips to establish Superman's backstory, adding details such as the planet Krypton and Superman's father, Jor-El, concepts not yet established in the comic books.[71] Following on from the success of this was the first radio series, The Adventures of Superman, which premiered on February 12, 1940 and featured the voice of Bud Collyer as Superman. The series ran until March, 1951. Collyer was also cast as the voice of Superman in a series of Superman animated cartoons produced by Fleischer Studios and Famous Studios for theatrical release. Seventeen shorts were produced between 1941 and 1943. By 1948 Superman was back in the movie theatres, this time in a filmed serial, Superman, with Kirk Alyn becoming the first actor to portray Superman on screen. A second serial, Atom Man vs. Superman, followed in 1950.[127]

In 1951 a television series was commissioned, Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves, with the pilot episode of the series gaining a theatrical release as Superman and the Mole Men. The series ran for a 104 episodes, from 1952–1958. The next adaptation of Superman occurred in 1966, when Superman was adapted for the stage in the Broadway musical It's a Bird...It's a Plane...It's Superman. Despite good reviews, the play closed after only 129 performances.[128] The original cast album recording was released and continues to be available.[129] However, in 1975 the play was remade for television. Superman was again animated, this time for television, in the series The New Adventures of Superman. 68 shorts were made and broadcast between 1966 and 1969. Bud Collyer again provided the voice for Superman. Then from 1973 until 1984 ABC broadcast the Super Friends series, this time animated by Hanna-Barbera.[130]

Superman returned to movie theatres in 1978, with director Richard Donner's Superman starring Christopher Reeve. The film spawned three sequels, Superman II (1980), Superman III (1983) and Superman IV: The Quest For Peace (1987).[131] In 1988 Superman returned to television in the Ruby Spears animated series Superman,[132] and also in Superboy, a live-action series which ran from 1988 until 1992.[133] In 1993 Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman premiered on television, starring Dean Cain as Superman and Teri Hatcher as Lois Lane. The series ran until 1997. Superman: The Animated Series was produced by Warner Bros. and ran from 1996 until 2000 on The WB Television Network.[134] In 2001, the Smallville television series launched, focussing on the adventures of Clark Kent as a teenager before he dons the mantle of Superman.[135] In 2006, Bryan Singer directed Superman Returns, starring Brandon Routh as Superman.[136]

Musical references, parodies, and homages

Superman has also featured as an inspiration for musicians, with songs by numerous artists from several generations celebrating the character. Donovan's Billboard Hot 100 topping single "Sunshine Superman" utilised the character in both the title and the lyric, declaring "Superman and Green Lantern ain't got nothing on me".[137] Other tracks to reference the character include Genesis' "Land of Confusion",[138] the video to which featured a Spitting Image puppet of Ronald Reagan dressed as Superman,[139] "(Wish I Could Fly Like) Superman" by The Kinks on their 1979 album Low Budget and "Superman" by The Clique, a track later covered by R.E.M. on its 1986 album Lifes Rich Pageant. This cover is referenced by Grant Morrison in Animal Man, in which Superman meets the character, and the track comes on Animal Man's walkman immediately after.[140]

Parodies of Superman did not take long to appear, with Mighty Mouse introduced in "The Mouse of Tomorrow" animated short in 1942.[141] Whilst the character swiftly took on a life of its own, moving beyond parody, other animated characters soon took their turn to parody the character. In 1943 Bugs Bunny was featured in a short, Super-Rabbit, which sees the character gaining powers through eating fortified carrots. This short ends with Bugs stepping into a phone booth to change into a real "Superman", and emerging as a U.S. Marine.[142] In 1956 Daffy Duck assumes the mantle of "Cluck Trent" in the short "Stupor Duck", a role later reprised in various issues of the Looney Tunes comic book.[143][144] In the United Kingdom Monty Python created the character Bicycle Repairman, who fixes bicycles on a world full of Supermen, for a sketch in series of their BBC show.[145] Also on the BBC was the sit-com "My Hero", which presented Thermoman as a slightly dense Superman pastiche, attempting to save the world and pursue romantic aspirations.[146] In the United States, Saturday Night Live has often parodied the figure, with Margot Kidder reprising her role as Lois Lane in a 1979 episode.[147] Jerry Seinfeld, a noted Superman fan, filled his series Seinfeld with references to the character, and in 1997 asked for Superman to co-star with him in a commercial for American Express. The commercial aired during the 1998 NFL Playoffs and Super Bowl, Superman animated in the style of artist Curt Swan, again at the request of Seinfeld.[148]

In PS 238, by Aaron Williams, the character Atlas, from the planet Argon, is basically a parody of Superman.

Superman has also been used as reference point for writers, with Steven T. Seagle's graphic novel Superman: It's a Bird exploring Seagle's feelings on his own mortality as he struggles to develop a story for a Superman tale.[149] Brad Fraser used the character as a reference point for his play Poor Super Man, with The Independent noting the central character, a gay man who has lost many friends to AIDS as someone who "identifies all the more keenly with Superman's alien-amid-deceptive-lookalikes status."[150]

Literary analysis

Superman has been interpreted and discussed in many forms in the years since his debut. The character's status as the first costumed superhero has allowed him to be used in many studies discussing the genre, Umberto Eco noting that "he can be seen as the representative of all his similars".[151] Writing in Time Magazine in 1971, Gerald Clarke stated: "Superman's enormous popularity might be looked upon as signalling the beginning of the end for the Horatio Alger myth of the self-made man." Clarke viewed the comics characters as having to continuously update in order to maintain relevance, and thus representing the mood of the nation. He regarded Superman's character in the early seventies as a comment on the modern world, which he saw as a place in which "only the man with superpowers can survive and prosper."[152] Andrew Arnold, writing in the early 21st century, has noted Superman's partial role in exploring assimilation, the character's alien status allowing the reader to explore attempts to fit in on a somewhat superficial level.[153]

A.C. Grayling, writing in The Spectator, traces Superman's stances through the decades, from his 1930s campaign against crime being relevant to a nation under the influence of Al Capone, through the 1940s and World War II, a period in which Superman helped sell war bonds,[154] and into the 1950s, where Superman explored the new technological threats. Grayling notes the period after the Cold War as being one where "matters become merely personal: the task of pitting his brawn against the brains of Lex Luthor and Brainiac appeared to be independent of bigger questions", and discusses events post 9/11, stating that as a nation "caught between the terrifying George W. Bush and the terrorist Osama bin Laden, America is in earnest need of a Saviour for everything from the minor inconveniences to the major horrors of world catastrophe. And here he is, the down-home clean-cut boy in the blue tights and red cape".[155]

Scott Bukatman has discussed Superman, and the superhero in general, noting the ways in which they humanize large urban areas through their use of the space, especially in Superman's ability to soar over the large skyscrapers of Metropolis. He writes that the character "represented, in 1938, a kind of Corbusierian ideal. Superman has X-ray vision: walls become permeable, transparent. Through his benign, controlled authority, Superman renders the city open, modernist and democratic; he furthers a sense that Le Corbusier described in 1925, namely, that 'Everything is known to us'."[38]

Jules Feiffer has argued that Superman's real innovation lay in the creation of the Clark Kent persona, noting that what "made Superman extraordinary was his point of origin: Clark Kent." Feiffer develops the theme to establish Superman's popularity in simple wish fulfilment,[156] a point Siegel and Shuster themselves supported, Siegel commenting that "If you're interested in what made Superman what it is, here's one of the keys to what made it universally acceptable. Joe and I had certain inhibitions... which led to wish-fulfillment which we expressed through our interest in science fiction and our comic strip. That's where the dual-identity concept came from" and Shuster supporting that as being "why so many people could relate to it".[157]

Superman's immigrant status is a key aspect of his appeal.[158][159][160] Aldo Regalado saw the character as pushing the boundaries of acceptance in America. The extraterrestrial origin was seen by Regalado as challenging the notion that Anglo-Saxon ancestry was the source of all might.[161] Gary Engle saw the "myth of Superman [asserting] with total confidence and a childlike innocence the value of the immigrant in American culture." He argues that Superman allowed the superhero genre to take over from the Western as the expression of immigrant sensibilities. Through the use of a dual identity, Superman allowed immigrants to identify with both their cultures. Clark Kent represents the assimilated individual, allowing Superman to express the immigrants cultural heritage for the greater good.[159] Timothy Aaron Pevey has argued other aspects of the story reinforce the acceptance of the American dream. He notes that "the only thing capable of harming Superman is Kryptonite, a piece of his old home world."[37] David Jenemann has offered a contrasting view. He argues that Superman's early stories portray a threat: "the possibility that the exile would overwhelm the country."[162]

Critical reception and popularity

The character Superman and his various comic series have received various awards over the years. The Reign of the Supermen is one of many storylines or works to have received a Comics Buyer's Guide Fan Award, winning the Favorite Comic Book Story category in 1993.[163] Superman came at number 2 in VH1's Top Pop Culture Icons 2004.[164] In the same year British cinemagoers voted Superman as the greatest superhero of all time.[165] Works featuring the character have also garnered six Eisner Awards[166][167] and three Harvey Awards,[168] either for the works themselves or the creators of the works. The Superman films have, as of 2007, received a number of nominations and awards, with Christopher Reeve winning a BAFTA for his performance in Superman.[169] The Smallville television series has garnered Emmys for crew members and various other awards.[170] Superman as a character is still seen as being as relevant now as he has been in the seventy years of his existence.[171]

Notes

- ^ a b Daniels (1998), p. 11.

- ^ Holt, Douglas B. (2004). How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. p. 1. ISBN 1578517745.

- ^ Koehler, Derek J., Harvey, Nigel. (eds.), ed. (2004). Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making. Blackwell. p. 519. ISBN 1405107464.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Dinerstein, Joel (2003). Swinging the machine: Modernity, technology, and African American culture between the wars. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 81. ISBN 1558493832.

- ^ a b c d e f Daniels (1998), p. 18.

- ^ Wallace, Daniel (2006). The Art of Superman Returns. Chronicle Books. p. 22. ISBN 0811853446.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Designing Man of Steel's costume". Manila Standard. Philippines News. July 21, 2006. Retrieved 2008-09-03. Archived 2008-09-03.

- ^ Gormly, Kellie B. (June 28, 2006). "Briefs: Blige concert cancelled". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved 2008-09-03. [Archived http://www.webcitation.org/5aYbcuH9Z] on 2008-09-03.

- ^ McCollum, Charlie (June 2006). "Times change, but Superman endures as an American cultural icon" (Registration required). The Mercury News. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Epstein, Daniel Robert (July 30, 2006). "4:11 with Bryan Singer". Newsarama. Retrieved 2007-01-30. Archived September 9, 2009.

- ^ Niven, Larry (1971). "Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex". All the Myriad Ways. Larry Niven. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ a b Daniels (1998), p. 13.

- ^ a b Roger Stern. Superman: Sunday Classics: 1939 - 1943 DC Comics/Kitchen Sink Press, Inc./Sterling Publishing; 2006; Page xii

- ^ a b Gross, John (December 15, 1987). "Books of the Times". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 17.

- ^ a b c Jones, Gerard (2004). Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. Basic Books. p. 115. ISBN 0465036562.

- ^ Trexler, Jeff (August 20, 2008). "Superman's Hidden History: The Other "First" Artist". Newsarama. Imaginova Corp. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Archived August 26, 2008. - ^ Petrou, David Michael (1978). The Making of Superman the Movie, New York: Warner Books ISBN 0-446-82565-4

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 19.

- ^ Morrison, Grant (September 29, 1998). "Seriously, Perilously". The Herald. p. 14.

- ^ Engle, Gary (1987). ""What Makes Superman So Darned American?"". In Dennis Dooley and Gary Engle (eds.) (ed.). Superman at Fifty: The Persistence of a Legend. Cleveland, OH: Octavia. ISBN 0020429010.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Andrae, Nemo (online version): "Superman Through the Ages: The Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster Interview, Part 8 of 10" (1983).

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 25–31.

- ^ David Colton (2008-08-25). "The crime that created Superman: Did fatal robbery spawn Man of Steel?". USAToday.com. Archived from the original on 2008-08-26. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ a b Daniels (1998), p. 44.

- ^ Fox, Gardner (w), Hibbard, Everett E. (a). "$1,000,000 for War Orphans" All Star Comics, vol. 1, no. 7 (October-November 1941). All-American Publications.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 13

- ^ a b Daniels (1998), p. 69.

- ^ Eury (2006), p. 38.

- ^ Daniels (1995), p. 28.

- ^ Moore, Alan (w), Swan, Curt (p), Pérez, George & Schaffenberger, Kurt (i). Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (1997). DC Comics, ISBN 1-56389-315-0.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 150.

- ^ a b Daniels (1995), pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Sabin, Roger (1996). Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels (4th paperback ed.). Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-3993-0.

- ^ von Busack, Richard (July 2 – July 8, 1998). "Superman Versus the KKK". Metro. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dubner, Stephen J (January 8, 2006). "Hoodwinked?". The New York Times. p. F26. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Pevey, Timothy Aaron "Template:Pdf. 2007-04-10 URN: etd-04172007-133407

- ^ a b Bukatman, Scott (2003). Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th century. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822331322.

- ^ Feeley, Gregory (2005). "When World-views Collide: Philip Wylie in the Twenty-first Century". Science Fiction Studies. 32 (95). ISSN 0091-7729. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Steranko, Jim (1970). The Steranko History of Comics. Vol. 1. Supergraphics. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-517-50188-0.

- ^ a b Jacobson, Howard (March 5, 2005). "Up, up and oy vey". The Times. p. 5.

- ^ a b c The Mythology of Superman (DVD). Warner Bros. 2006.

- ^ Weinstein, Simcha (2006). Up, Up, and Oy Vey! (1st ed.). Leviathan Press. ISBN 978-1-881927-32-7.

- ^ World Jewish Digest (Aug, 2006; posted online July 25, 2006): "Superman's Other Secret Identity", by Jeff Fleischer

- ^ "Semitic Roots." The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2000). 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved on 2007-02-08.

- ^ a b Waldman, Steven (June 19, 2006). "Beliefwatch: Good Fight". Newsweek. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Skelton, Stephen. The Gospel According to the World's Greatest Superhero. Harvest House Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-7369-1812-4.

- ^ McCue, Greg S., Bloom, Clive (February 1, 1993). Dark Knights, LPC Group. ISBN 0745306632.

- ^ Lawrence, John Shelton (2006). "Book Reviews: The Gospel According to Superheroes: Religion and Popular Culture". The Journal of American Culture. 29 (1): 101. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2006.00313.x. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Andrae (1983), p.2.

- ^ Andrae (1983), p.4.

- ^ Andrae (1983), p.7.

- ^ Andrae (1983), p.5.

- ^ Hurwitt, Sam (January 16, 2005). "Comic Book Artist Populates Movies". San Francisco Chronicle. p. PK-24. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Heidi. "Inside the Superboy Copyright Decision.' PW Comics Week (April 11, 2006). Available online at Publishers Weekly, Retrieved on 2006-12-08. Archived 2009-02-12.

- ^ a b Dean (2004), p. 16.

- ^ Dean (2004), p. 13.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 73.

- ^ Dean (2004), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Dean (2004), p. 17.

- ^ Vosper, Robert (2005). "The Woman Of Steel". Inside Counsel. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

DC isn't going to hand over its most valued asset without putting up one hell of a legal battle

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brady, Matt (March 3, 2005). "Inside The Siegel/DC Battle For Superman". Newsarama. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

While the complaint, response and counterclaim has been filed, no one even remotely expects a slam-dunk win for either side. Issues such as those named in the complaint will, if it goes to trial, possibly allow for an unprecedented referendum on issues of copyright.

- ^ a b Ciepley, Michael. "Ruling Gives Heirs a Share of Superman Copyright" NY Times, March 29, 2008. Accessed on 2008-03-29. Archived on 2008-03-29.

- ^ Agency reporter, Bloomberg News, "Time Warner ordered to share Superman rights". LA Times, March 29, 2008. '"After 70 years, Jerome Siegel's heirs regain what he granted so long ago -- the copyright in the Superman material that was published in Action Comics," Larson wrote in his order Wednesday. The victory was "no small feat indeed," he said.' Accessed on 2008-03-29. Archived on 2008-03-29.

- ^ Coyle, Marcia. "Pow! Zap! Comic Book Suits Abound". The National Law Journal, February 4, 2008. Retrieved on 2008-02-17. Archived on 2008-02-17.

- ^ Dean, Michael (2006). "Journal Datebook: Follow-Up: Superman Heirs Reclaim Superboy Copyright". The Comics Journal (276): 37.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Case 2:04-cv-08776-SGL-RZ Document 151" (PDF). July 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ McNary, Dave (2009-07-09). "Warner Bros. wins 'Superman' case". Variety.com. Variety. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ^ a b Friedrich, Otto (March 14, 1988). "Up, Up and Awaaay!!!". Time Magazine. p. 9. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Daniels (1998), p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Daniels (1998), p. 42.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis (w), Dillin, Dick (p), Greene, Sid (i). "Star Light, Star Bright — Death Star I See Tonight!" Justice League of America, vol. 1, no. 73 (August, 1969). DC Comics.

- ^ Byrne, John (w)(p), Giordano, Dick (i). The Man of Steel Ed. Barry Marx. DC Comics, 1987. ISBN 0-930289-28-5.

- ^ Jurgens, Dan, Ordway, Jerry, Simonson, Louise et al. (w), Jurgens, Dan, Guice, Jackson, Bogdanove, Jon, et al. (p), Rodier, Denis, Janke, Dennis, Breeding, Brett et al. (i). The Death of Superman Ed. Mike Carlin. NY:DC Comics, April 14, 1993. ISBN 1-56389-097-6.

- ^ Jurgens, Dan, Kesel, Karl, Simonson, Louise et al. (w), Jurgens, Dan, Guice, Jackson, Bogdanove, Jon, et al. (p), Rodier, Denis, Janke, Dennis, Breeding, Brett et al. (i). The Return of Superman (Reign of the Supermen) Ed. Mike Carlin. NY:DC Comics, September 3, 1993. ISBN 1-56389-149-2.

- ^ Waid, Mark (w), Yu, Leinil Francis (a). Superman: Birthright. NY:DC Comics, October 1, 2005. ISBN 1-4012-0252-7.

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Jimenez, Phil, Pérez, George, Ordway, Jerry et al. (a). Infinite Crisis. NY:DC Comics, September 20, 2006. ISBN 1401209599 ISBN 978-1401209599

- ^ Johns, Geoff, Busiek, Kurt (w), Woods, Peter, Guedes, Renato (a). Superman: Up, Up and Away! NY:DC Comics, 2006. ISBN 1401209548 ISBN 978-1401209544.

- ^ Rucka, Greg (w), Lopez, David (p). "Affirmative Defense" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 220 (October 2005). DC Comics.

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Conner, Amanda (p), Palmiotti, Jimmy (i). "Power Trip" JSA: Classified, vol. 1, no. 1 (September 2005). DC Comics.

- ^ Johns, Geoff Donner, Richard (w), Wight, Eric (p), Wight, Eric (i). "Who is Clark Kent's Big Brother?" Action Comics Annual, vol. 1, no. 10 (March 2007). DC Comics.

- ^ Buskiek, Kurt, Nicieza, Fabian, Johns, Geoff (w), Guedes, Renato (p), Magalhaes, Jose Wilson (i). "Superman: Family" Action Comics, vol. 1, no. 850 (July 2007). DC Comics.

- ^ Loeb, Jeph (w), McGuinness, Ed (p), Vines, Dexter (i). "Running Wild" Superman/Batman, vol. 1, no. 3 (December 2003). DC Comics.

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Jimenez, Phil (p), Lanning, Andy (i). "Infinite Crisis" Infinite Crisis, vol. 1, no. 1 (December 2005). DC Comics.

- ^ Jurgens et al.. The Return of Superman (1993).

- ^ Dooley, Dennis and Engle, Gary D. Superman at Fifty! (1988)

- ^ Interview with Roy Thomas and Jerry Bails in The Justice League Companion (2003) pp. 72–73

- ^ Wolf-Meyer, Matthew (2003). "The World Ozymandias Made: Utopias in the Superhero Comic, Subculture, and the Conservation of Difference". The Journal of Popular Culture. 36 (3): 497–517. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00019. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

... will fail to emerge). Hyperion, the Superman-clone of Squadron Supreme, begins the series when he vows, on behalf of the Squadron ...

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bainbridge, Jason (2007). http://lch.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/3/3/455 ""This is the Authority. This Planet is Under Our Protection" — An Exegesis of Superheroes' Interrogations of Law". Law, Culture and the Humanities. 3 (3): 455–476. doi:10.1177/1743872107081431. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

The trend begins in 1985 when Mark Gruenwald's Squadron Supreme (Marvel's thinly veiled version of DC's Justice League) take over their (parallel) Earth implementing a benign dictatorship to usher in...

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Thomas, Roy. Bails, Jerry. The Justice League Companion (2003) pp. 72–73. (Roy Thomas discusses the creation of Squadron Supreme, his Justice League parody.

- ^ "Obituaries of note". St. Petersburg Times. Wire services. September 25, 2003. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ a b c Daniels (1995), p. 80.

- ^ Siegel, Jerry (w), Shuster, Joe (a). "A Scientific Explanation of Superman's Amazing Strength--!" Superman, vol. 1, no. 1 (Summer 1939). National Periodical Publications.

- ^ Cabarga, Leslie, Beck, Jerry, Fleischer, Richard (Interviewees). (2006). "First Flight: The Fleischer Superman Series" (supplementary DVD documentary). Superman II (Two-Disc Special Edition) [DVD]. Warner Bros..

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 133.

- ^ a b Sanderson, Peter (1986). "The End of History". Amazing Heroes (96). ISSN 0745-6506.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lundegaard, Erik (July 3, 2006). "Sex and the Superman". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

Even his origin kept changing. Initially Krypton was populated by a race of supermen whose physical structure was millions of years more advanced than our own. Eventually the red sun/yellow sun dynamic was introduced, where Superman's level of power is dependent upon the amount of yellow solar radiation his cells have absorbed.

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Zeno, Eddy (December 25, 2006). "From Back Issue 20: Pro 2 Pro: A Clark Kent Roundtable" (excerpted from "The Clark Kent Roundtable". Back Issue (20). 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)). newsarama.com. published on web by newsarama, in print by TwoMorrow. Retrieved 2007-01-31.{{cite web}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|format=at position 16 (help) - ^ a b Eury (2006), p. 119.

- ^ "Superman's LL's [Text page]" Superman, no. 204 (February, 1968). DC Comics.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 160.

- ^ , DeMatteis, J.M., Kelly, Joe, Loeb, Jeph et al. (w), McGuinness, Ed, Rouleau, Duncan, Medina, Paco (a). Superman: President Lex, NY:DC Comics, July 1, 2003. ISBN 1563899744, ISBN 978-1563899744

- ^ George, Richard (2006-06-22). "Superman's Dirty Dozen". IGN. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ Magnussen, Anne (2000). Comics & Culture: Analytical and Theoretical Approaches to Comics. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 8772895802.

a metaphor and cultural icon for the 21st century

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); line feed character in|coauthors=at position 15 (help) - ^ Postmes, Tom (2006). Individuality and the Group: Advances in Social Identity. Sage Publications. ISBN 1412903211.

American cultural icons (e.g., the American Flag, Superman, the Statue of Liberty)

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); line feed character in|coauthors=at position 8 (help) - ^ Soanes, C. and Stevenson, A. 2004. Electronic version of The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Eleventh Edition. England: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bizarro reference Reference to Bizzaro logic in FCC pleading.

- ^ "You're not Superman: Despite major medical advances, recovery times for regular folks take time" on PhysOrg.com http://www.physorg.com/news160411454.html (accessed 5th of October 2009)

- ^ "You're Not Superman, You Know" on scarleteen.com http://www.scarleteen.com/blog/abbie/2009/05/25/youre_not_superman_you_know (accessed 5th of October 2009)

- ^ "Stress In The Modern World – Face It Guys, You’re Not Superman" on natural-holistic-health.com http://www.natural-holistic-health.com/general/mens-health/stress-modern-world-face-guys/ (accessed 5th of October 2009)

- ^ Eury (2006), p. 116: "since Superman inspired so many different super-heroes".

- ^ Hatfield, Charles (2006) [2005]. Alternative Comics: an emerging literature. University Press of Mississippi. p. 10. ISBN 1578067197.

the various Superman-inspired "costume" comics

- ^ Daniels (1995), p. 34.

- ^ Lloyd L. Rich. "Protection of Graphic Characters". Publishing Law Center. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

the court found that the character Superman was infringed in a competing comic book publication featuring the character Wonderman

- ^ Daniels (1995), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Singer, Marc (2002). ""Black Skins" and White Masks: Comic Books and the Secret of Race" (embedded image of first page). African American Review. 36 (1): 107–119. doi:10.2307/2903369. Retrieved January 16, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ South Carolina PACT Coach, English Language Arts Grade 5. Triumph Learning. 2006. ISBN 1598230778.

- ^ Staff writer. "Superman Struts In Macy Parade". New York Times, November 22, 1940. p.18

- ^ Staff writer (April 13, 1942). "Superman's Dilemma". Time. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b Daniels (1998), p. 50.

- ^ Karl Heitmueller (June 13, 2006). "The 'Superman' Fanboy Dilemma, Part 4: Come On Feel The Toyz" (Flash). MTV News. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

Warner Bros. has "Superman Returns" licensing deals with Mattel, Pepsi, Burger King, Duracell, Samsung, EA Games and Quaker State Motor Oil, to name a few.

- ^ Lieberman, David (June 21, 2005). "Classics are back in licensed gear". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Consumer Products Flies High with DC's Superman at Licensing 2005 International; Franchise Set to Reach New Heights in 2005 Leading Up to Feature Film Release of Superman Returns in June 2006" (Press release). Business Wire. June 16, 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

With a super hero that transcends all demographics" ... and ... "S-Shield, which continues to be a fashion symbol and hot trend

- ^ Jones, Cary M. (2006). "Smallville and New Media mythmaking; Twenty-first century Superman". Jump Cut (48). Retrieved 2008-07-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Juddery, Mark (October 2000). "Jacob 'Jack' Liebowitz". The Australian. Mark Juddery. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

Superman's popularity increased during the war years, spinning off into a comic strip

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Holiday, Bob & Harter, Chuck. Superman on Broadway, 2003

- ^ "Amazon.com: It's A Bird ... It's A Plane ... It's Superman (1966 Original Broadway Cast): Music: Charles Strouse, Lee Adams". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 111–115

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 141–143

- ^ "About Us". Ruby-Spears website. Ruby-Spears Productions. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

Ruby-Spears pulled the coup of the 1988–89 season by acquiring the rights to two heavily sought after properties. Debuting that September on CBS was the classic, Superman, which celebrated its 50th anniversary, and it was with much acclaim that Ruby-Spears was selected to produce the animated series for the network schedule.

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 164–165.

- ^ Daniels (1998), pp. 172–174.

- ^ ""Smallville" (2001)". imdb.com. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ "Superman Returns (2006)". imdb.com. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ Donovan. "Sunshine Superman." Sunshine Superman. Epic, 1966.

- ^ Genesis. "Land of Confusion." Invisible Touch. Atlantic Records, 1986. "Ooh Superman where are you now, When everything's gone wrong somehow".

- ^ Lloyd, John & Yukich, Jim (Directors) (1986). "Land of Confusion" (Music video). Atlantic Records.

- ^ Morrison (w), Grant (2002) [1991]. "2: Life In The Concrete Jungle". In Michael Charles Hill (ed.) (ed.). Animal Man. John Costanza (letterer) & Tatjana Wood (colorist) (1st ed.). New York: DC Comics. p. 45. ISBN 1-56389-005-4.

R.E.M. starts singing "Superman." My arm aches and I've got déjà vu. Funny how everything comes together.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Turner, Robin (August 8, 2006). "Deputy Dawg". Western Mail. Western Mail and Echo Ltd. p. 21.

- ^ "Super-Rabbit (1943)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Stupor Duck (1956)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Looney Tunes # 97". Big Comicbook Database. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ Clarke, Mel (August 1, 2004). "The Pitch". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers Ltd. p. 34.

- ^ Kinnes, Sally (January 30, 2000). "The One To Watch". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers Ltd. p. 58.

- ^ ""Saturday Night Live" Episode #4.15 (1979)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ Daniels (1998), p. 185.

- ^ "Steven Seagle Talks It's a Bird". ugo.com. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

the semi-autobiographical tale of Steven being given the chance to write a Superman comic, but stumbling when he can't figure out how to relate to the character. Through the course of the story, Seagle finds his way into Superman by looking at it through the lens of his own mortality.

- ^ Taylor, Paul (September 21, 1994). "Theatre". The Independent. Independent News & Media.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (2004). "The Myth of Superman". In Jeet Heer & Kent Worcester (ed.). Arguing Comics. University Press of Mississippi. p. 162. ISBN 1-57806-687-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Clarke, Gerald (December 13, 1971). "The Comics On The Couch". Time. Time Warner. pp. 1–4. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Arnold, Andrew. "The Hard Knock Life". Time. Time Warner. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

much of The Quitter involves the classic American literary theme of assimilation. Though extremely popular in other mediums, this theme, again, has gotten little attention in comix except obliquely, through such genre works as Seigel and Shuster's Superman character.

- ^ Daniels (1995), p. 64.

- ^ Grayling, A C (July 8, 2006). "The Philosophy of Superman: A Short Course" (Fee required). The Spectator. Press Holdings. ISSN 0038-6952. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Jules Feiffer The Great Comic Book Heroes, (2003). Fantagraphics. ISBN 1-56097-501-6

- ^ Andrae (1983), p.10.

- ^ Fingeroth, Danny Superman on the Couch (2004). Continuum International Publishing Group p53. ISBN 0826415393

- ^ a b Engle, Gary "What Makes Superman So Darned American?" reprinted in Popular Culture (1992) Popular Press p331-343. ISBN 0879725729

- ^ Wallace, Daniel (2006). The Art of Superman Returns. Chronicle Books. p. 92. ISBN 0811853446.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Regalado, Aldo "Modernity, Race, and the American Superhero" in McLaughlin, Jeff (ed.) Comics as Philosophy (2005). Univ of Mississippi Press p92. ISBN 1578067944

- ^ Jenemann, David (2007). Adorno in America. U of Minnesota Press. p. 180. ISBN 0816648093.

- ^ Miller, John Jackson (June 9, 2005). "CBG Fan Awards Archives". www.cbgxtra.com. Krause Publications. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

CBG Fan Award winners 1982–present

- ^ "200 Greatest Pop Culture Icons List: The Folks that Have Impacted American Society". Arizona Reporter. October 27, 2003. Retrieved 2006-12-08. Syndicated reprint of a Newsweek article

- ^ "Superman is 'greatest superhero'". BBC. 2004-12-22. Retrieved 2007-02-18.