United States–Venezuela relations

This article appears to be slanted towards recent events. (December 2014) |

| |

United States |

Venezuela |

|---|---|

United States–Venezuela relations are the bilateral relations between the United States of America and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Both countries maintained mutual diplomatic relationships since the early-19th century traditionally been characterized by an important trade and investment relationship and cooperation in controlling the production and transit of illegal drugs. Relations were strong under conservative [citation needed] governments in Venezuela like that of Rafael Caldera. However, tensions increased after the socialist President Hugo Chávez assumed elected office in 1999. Tensions between the countries increased after Venezuela accused the administration of George W. Bush of supporting the Venezuelan failed coup attempt in 2002 against Chavez.[neutrality is disputed] Venezuela broke off diplomatic relations with the U.S. in September 2008 in solidarity with Bolivia after a U.S. ambassador was accused of cooperating with violent anti-government groups in that country, though relations were reestablished under President Barack Obama in June 2009. In February 2014, the Venezuelan government ordered three American diplomats to leave the country on charges of promoting violence.[1]

Relations between the two countries have plunged to their worst level in years after the United States imposed economic sanctions against the Government of Venezuela due to alleged abuses against protesters during the 2014–15 Venezuelan protests and allegations by the Venezuelan government that the United States was attempting to institute a coup.

Early history

Venezuela and United States's ties go back to 1806 when Venezuela was still under Spanish rule, at that time Francisco de Miranda, a Venezuelan soldier, filibuster and adventurer, unsuccessfully attempted to liberate his country with the aid of U.S. government.[2] Miranda went to Washington for private meetings with President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison, who talk with Miranda but did not involve themselves or their nation in his plans, which would have been a violation of the Neutrality Act of 1794. In New York Miranda privately began organizing a filibustering expedition with 200 volunteers and hired a ship of 20 guns rebaptized Leander and set sail to Venezuela on February 2, 1806. On April 28, a botched landing attempt in Ocumare de la Costa sixty men were imprisoned and put on trial in Puerto Cabello, and ten American expeditionaries were sentenced to death.

Following the events of the Revolution of April 19, 1810, the Captain General Vicente Emparan and other colonial officials designated by Joseph Bonaparte to govern the Captaincy General of Venezuela, were deposed by an expanded municipal government in Caracas that called itself: the Supreme Junta to Preserve the Rights of Ferdinand VII (La Suprema Junta Conservadora de los Derechos de Fernando VII). One of the first measures of revolutionaries after securing the support of six provinces was to send diplomatic missions to Britain, United States, New Granada, Curazao, Jamaica and Trinidad to seek the recognition of the Supreme Junta of Caracas as the legitimate councilor of Venezuela in the absence of the King. To the United States were sent Juan Vicente Bolívar Palacios, brother of the Liberator Simon Bolívar, Jose Rafael Revenga and Telesforo Orea who obtained some success in interesting the government of president James Madison to support the Supreme Junta.

In June 1817, Gregor MacGregor, a Scottish adventurer styling himself the "Brigadier General of the United Provinces of New Granada and Venezuela and General-in-Chief of the Armies of the Two Floridas", came to Amelia Island Florida under Spanish rule. MacGregor, purportedly commissioned by Simon Bolivar, had raised funds and troops in Savannah (Georgia) for a full-scale invasion of Florida, but squandered much of the money on luxuries; as word of his conduct in the South American wars, many of the recruits in his invasion force deserted. Nonetheless, he overran the island with a small force, but left for Nassau in September. His followers were soon joined by Louis-Michel Aury, formerly associated with MacGregor in South American adventures,[3] and previously one of the leaders of a group of buccaneers on Galveston Island, Texas.[4][5][6] Aury assumed control of Amelia,[7] created an administrative body called the "Supreme Council of the Floridas",[8] directed his secretaries Pedro Gual Escandón and Vicente Pazos to draw up a constitution,[9] and invited all Florida to unite in throwing off the Spanish yoke. For the few months that Aury controlled Amelia Island,[10] the flag of the revolutionary Republic of Mexico was flown.[11] This was the flag of his supposed clients who were still fighting the Spanish in their war for independence at that time. The U.S. government of president James Monroe, which had plans to annex the peninsula, sent a naval force which captured Amelia Island on December 23, 1817.[12]

The Anderson–Gual Treaty

The Anderson–Gual Treaty (formally, the General Convention of Peace, Amity, Navigation, and Commerce) was an 1824 treaty between the United States and Gran Colombia integrated by modern-day countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama and Ecuador. It is the first bilateral treaty that the United States concluded with another American country under Monroe Doctrine.

The treaty was signed in Bogotá on October 3, 1824 by U.S. diplomat Richard Clough Anderson and by chancellor Pedro Gual Escandón. The first U.S. consulate in the present-day territory of Venezuela was established in port city of Maracaibo in 1824. The treaty was ratified by both countries and entered into force in May 1825.

The commercial provisions of the treaty granted reciprocal most-favored-nation status was maintened despite the separation of the Gran Colombia in 1830. The treaty contained a clause that stated it would be in force for 12 years after ratification by both parties; the treaty therefore expired in 1836.

The Anfictional Congress of Panama

The notion of an international union in the New World was first put forward by the Venezuelan Liberator Simón Bolívar[13] who, at the 1826 Congress of Panama (still being part of Gran Colombia), proposed creating a league of American republics, with a common military, a mutual defense pact, and a supranational parliamentary assembly. Bolívar's dream of American unity was meant to unify Hispanic American nations against external powers include the United States. This meeting was attended by representatives of Gran Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, The United Provinces of Central America, and Mexico but the grandly titled "Treaty of Union, League, and Perpetual Confederation" was ultimately ratified only by Gran Colombia. Despite their eventual departure, of the two United States delegates envoyed by president John Quincy Adams, one (Richard Clough Anderson) died en route to Panama, and the other (John Sergeant) only arrived after the Congress had concluded its discussions. Thus Great Britain, which attended with only observer status, managed to acquire many good trade deals with Latin American countries. Bolívar's dream soon floundered with civil war in Gran Colombia, the disintegration of Central America, and the emergence of national rather than New World outlooks in the newly independent American republics.

Recognition of Republic of Venezuela

After separation of the Gran Colombian federation in 1830 the United States recognized the Republic of Venezuela on February 28, 1835 by issuing an exequatur to Nicholas D.C. Moller as the Venezuelan Consul in New York. Diplomatic relations were established on June 30, 1835, when U.S. Chargé d'Affaires John G.A. Williamson of U.S. Legation accreditated in Caracas presented his credentials to the Venezuelan Government. The first commercial treaty between the United States and the Republic of Venezuela was signed on January 20, 1836. Ratifications were exchanged on May 31, 1836, and it became effective on June 20 of that year.

Venezuela US debt crisis

In 1869 the government of Venezuela had been forced to sign an agreement with the United States, in which agreed to pay one and half million dollars in compensation for alleged damage to properties U.S. citizens in the country devastated by civil war.

One of the first actions of president Guzman Blanco in 1870 was to review the agreement and proceed to order a full assessment of the damage to these American citizens is made. These assessments resulted in the total cost of the damage did not rise more than five thousand dollars. Consequently, Guzman Blanco challenged the agreement and suspends payment of the debt. In addition, it begins to close several consulates, diplomatic missions and the U.S. legation in Caracas, actions that caused U.S. completely baffled, because the attitude of Venezuela, had never been seen before. The firmness of Guzman Blanco and his energetic handling of foreign affairs, made the Department of State being forced to rethink their strategies with Venezuela, to such an extent that it Guzman Blanco cried defiantly:

'Bring your guns and start shooting them, because Venezuela does not want to be robbed more diplomatically.' [14]

The situation extends to his third government, at the beginning of 1886, when after virtually all consulate, embassy or legation, was closed and after that Venezuela he preferred align more with European nations, especially France and Germany, at the time of grant for its concessions and realize projects, rather than the United States. Finally the US Senate, made a new contract, according to the standards established by Venezuela, while accepting the removal of the previous agreements.

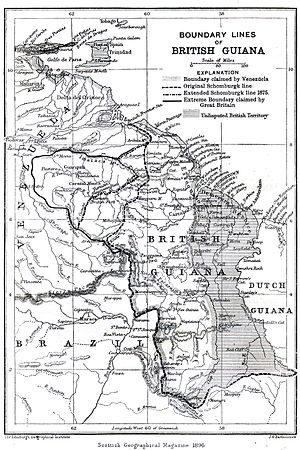

The Guayana Esequiba Crisis

* The extreme border claimed by Britain

* The current boundary (roughly) and

* The extreme border claimed by Venezuela

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895[a] occurred over Venezuela's longstanding dispute with the United Kingdom about the territory of Essequibo and Guayana Esequiba, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana and Venezuela saw as its own territory. As the dispute became a crisis, the key issue became Britain's refusal to include in the proposed international arbitration the territory east of the "Schomburgk Line", which a surveyor had drawn half a century earlier as a boundary between Venezuela and the former Dutch territory of British Guiana.[15] By December 17, 1895, President Grover Cleveland delivered an address to the United States Congress reaffirming the Monroe Doctrine and its relevance to the dispute. The crisis ultimately saw the Brtitain prime minister Lord Salisbury accept the United States' intervention to force arbitration of the entire disputed territory, and tacitly accept the United States' right to intervene under the Monroe Doctrine. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[16] The Anglo-Venezuelan boundary dispute asserted for the first time a more outward-looking American foreign policy, particularly in the Americas, marking the United States as a world power. This was the earliest example of modern interventionism under the Monroe Doctrine in which the USA exercised its claimed prerogatives in the Americas.[16][17]

The Roosevelt Corollary and Dollar Diplomacy

The Venezuela Crisis of 1902–03 saw a naval blockade of several months imposed against Venezuela by Britain, Germany and Italy over President Cipriano Castro's refusal to pay foreign debts and damages suffered by European citizens in a recent Venezuelan civil war financed partially by U.S. companies as The New York & Bermudez Company and Orinoco Steamship Company. Castro assumed that the Monroe Doctrine would see the U.S. prevent European military intervention, but at the time the president Theodore Roosevelt saw the Doctrine as concerning European seizure of territory, rather than intervention per se. Though U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root characterized Castro as a "crazy brute" or a "monkey" , President Roosevelt was concerned with the prospects of penetration into the region by Germany. With Castro failing to back down under U.S. pressure and increasingly negative British and American press reactions to the affair, the blockading nations agreed to a compromise, but maintained the blockade during negotiations over the details of refinacial the debt on Washington Protocols. This incident was a major driver of the Roosevelt Corollary and the subsequent U.S. Big Stick policy and Dollar Diplomacy in Latin America.

When American diplomat, Herbert Wolcott Bowen returned to Venezuela in January 1904 he noticed Venezuela seemed more peaceful and secure. Castro would reassure him that United States-Venezuela were at a high. However, after the Castro regime delayed fulfilling the agreements which ended the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–03, Bowen lost confidence. This would eventually lead to the Castro regime's to broke diplomatic relations with the United States, France, and the Netherlands.[18] This would play a crucial role in the Dutch–Venezuelan crisis of 1908. After verifying the contributions to rebels of U.S. firms The New York & Bermudez Company and Orinoco Steamship Company at the end of failed movement to overthrow Castro, the government demanded them compensation of 50 million bolivars, but as expected the companies refused to pay, then Castro ordered his expropriation, invalidating their operating contracts in Venezuela.

Under protection of battleships US Maine, US North Caroline and US Dolphin on December 19, 1908,[19] the vicepresident Juan Vicente Gomez seized power from Castro, while Castro was in Europe for medical treatment. As president, Gómez restaured diplomatic relations with United States and after the visit in Caracas of Secretary of State Philander C. Knox, this encouraged U.S. bankers to move into Venezuela and offer substantial loans to the new regime, thus increasing U.S. financial leverage over the country[citation needed]. Gomez managed to deflate Venezuela's staggering debt by granting concessions to foreign oil companies after the discovery of petroleum in Lake Maracaibo in 1914. This, in turn, won him the support of the United States and Europe and economic stability. The growth of the domestic oil industry strengthened the economic ties between the U.S. and Venezuela; however, it was established amid highly unequal power relations between the countries, with U.S. firms maintaining the upper hand.

Good neighbor diplomacy

After The Great Depression in 1929 the Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the first administration of Franklin Roosevelt toward the countries of Latin America. Giving up unpopular military intervention, the United States shifted to other methods to maintain its influence in its backyard: Pan-Americanism, support for strong local leaders, training of national guards, economic and cultural penetration, Export-Import Bank loans, financial supervision, and political subversion.

The negotiating of the reciprocal comercial agreement Venezuela United States concluded with the signing of the treaty in November 1939. The Lopez Contreras regime was convinced of the few benefits it would receive from the oil concessions and that the terms of the treaty were unfavorable; but fearing isolation from the process of global conclusion of trade agreements between other Latin American countries and afraid to conciliate possible discrimination by United States, the main commercial supplier and customer, and also conscious of European deteriorating political and pre war situation, decided to suggest the advisability of establishing a modus vivendi with a duration of one year was identical to the proposed Treaty.

In 1941, Isaías Medina Angarita, a former army general from the Venezuelan Andes, was indirectly elected president. One of his most important reforms during his tenure was the enactment of the new Hydrocarbons Law of 1943. This new law was the first major political step taken toward gaining more government control over Venezuelan oil industry managed by U.S. and British companies. Under the new law, the government took 50% of profits.[20][21] Once passed, this piece of legislation basically remained unchanged until 1976, the year of nationalization, with only two partial revisions being made in 1955 and 1967.[citation needed]. In 1944, the Medina visit to Washington by invitation of president Roosevelt, marked a milestone in the Venezuelan-US relations. Besides being the first time a Venezuelan president (in office) visited the United States, the journey was understood as an expression of the alliance of Venezuela with the Allies that fought the Axis in the World War II.

In 1944, the Venezuelan government granted several new concessions encouraging the discovery of even more oil fields. This was mostly attributed to an increase in oil demand caused by an ongoing World War II, and by 1945, Venezuela was producing close to 1 million barrels per day (160,000 m3/d). Being an avid supplier of petroleum to the Allies of World War II, Venezuela had increased its production by 42 percent from 1943 to 1944 alone.[22] Even after the war, oil demand continued to rise due to the fact that there was an increase from twenty-six million to forty million cars in service in the United States from 1945 to 1950.[23] During the administration of Medina, Venezuela establishes relations with China in 1943 and the Soviet Union in 1945. In October 18, 1945, Medina was overthrown by a combination of a military rebellion and a popular movement led by Democratic Action.[24] The coup led to a three-year period of government known as El Trienio Adeco, which saw the first democratic elections in Venezuelan history, beginning with the Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election, 1946. The Venezuelan general election, 1947 saw Democratic Action formally elected to office (with Rómulo Gallegos as President, replacing interim President Rómulo Betancourt), but it was removed from office shortly after in November 28 1948 Venezuelan coup d'état.

The Cold War

In light of the developing Cold War and following the statement of the Truman Doctrine, the US wished to make post war anti-communist commitments permanent. The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance was the first of many so-called 'mutual security agreements',[25] and the formalization of the Act of Chapultepec. The treaty was adopted by the original signatories, including Venezuela, on September 2, 1947 in Rio de Janeiro . It came into force on December 3, 1948 and was registered with the United Nations on December 20, 1948.[26]

In the XI Panamerican Conference (1954) organized in Caracas by government of general Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the Secretary of State John Foster Dulles lobbied on behalf of the American United Fruit Company to instigate a military coup in Guatemala under the pretext that Jacobo Árbenz's government and the Guatemalan Revolution were veering toward communism. Dulles had previously represented the United Fruit Company as a lawyer, and remained on its payroll, while his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, was on the company's board of directors.[27][28]

During his pro U.S. government policies, Pérez Jiménez undertook many infrastructure projects, including construction of roads, bridges, buildings, large public housing complexes. The economy of Venezuela developed rapidly during his term with the support of oil industry. Like most dictators, Pérez was not tolerant of criticism and his government ruthlessly pursued and suppressed the opponents of his regime that were painted as communists[29] and often treated brutally.[30] While Pérez Jimenez was president of Venezuela, the government of Dwight Eisenhower awarded him the U.S. Legion of Merit. By the mid-1950s, Middle Eastern countries had started contributing significant amounts of oil to the international petroleum market, and the Eisenhower administration implemented oil import quotas. The world experienced an over-supply of oil, prices plummeted and the regime was weakened by financial crisis.[citation needed] In this conditions Pérez Jiménez was up for reelection in 1957, but dispensed with constitution formalities. Instead, he held a plebiscite in which voters could only choose between voting "yes" or "no" to another term for the president. Predictably, Pérez Jiménez won by a large margin, though by all accounts the count was blatantly rigged. In January 23, 1958, there was a general uprising and, with rioting in the streets, Pérez Jimenez left the country, paving the way for the establishment of the Fourth Republic of Venezuela. He moved to the Miami, Florida, where he lived until 1963.

On April 27, 1958, vice president Richard Nixon embarked on a goodwill tour of South America. This tour prompted a spectacular eruption of anti-American violent protests which climaxed in Caracas, Venezuela where Nixon and his wife were almost killed by a raging mob as his motorcade drove from the airport to the city.[31][32] In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower assembled troops at Guantanamo Bay and a fleet of battleships in the Caribbean to intervene to save Nixon if necessary.[33]: 826–34 According to Stephen Ambrose, Nixon's courageous conduct "caused even some of his bitterest enemies to give him some grudging respect".

During the second democratic government of Venezuela of president Rómulo Betancourt (1959–1964), he was responsible for the creation of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) for the purpose of rationalizing and thereby increasing oil prices in the world market. Triggered by a 1960 law instituted by US President Dwight Eisenhower that forced quotas for Venezuelan oil and favored Canada and Mexico's industries, the mines and hydrocarbons minister Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo reacted seeking an alliance with oil producing Arab nations to protect the continuous autonomy and profitability of Venezuela's oil (among other reasons), establishing a strong link with the Middle East region that survives to this day. His extensive notes of the Texas Railroad Commission methods for regulation of production to maximize recovery served him well both in Venezuela and later when he took them translated into Arabic to El Cairo Oil Meeting, that served as launching platform for OPEC, where Wanda Jablonski introduced him to then minister of petroleum of Saudi Arabia, Abdullah Tariki, co-founder of OPEC.[34]

Betancourt's Democratic Action (Acción Democrática, AD) party largely disenfranchised the extreme left wing, notably the Communist Party of Venezuela (Partido Comunista de Venezuela, PCV).[clarification needed] The Cuban Revolution had influenced PCV and student groups hoping to repeat Fidel Castro's success in Venezuela. Many leftist students formed the Revolutionary Left Movement (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, MIR) in April 1960. In December 1961 the US President John F. Kennedy toured for Puerto Rico, Venezuela[35] and Colombia that were promoted as antagonistic Democratic bastions of Castro communism.

Betancourt instituted the idealistic foreign policy that Venezuela would not recognize dictatorial government anywhere, particularly in Latin America, but including the Soviet Union, an interpretation that pleased the United States. The "Betancourt doctrine" proved unrealistic, for Venezuelan democratization occurred in the midst of a marked tendency in the rest of Latin America towards authoritarianism, right or left, that came to power by military force. This put him at odds with the military strongmen (include that supported by U.S. government) who came to dominate and define political perception of the region. He was also unrealistic in reviving Venezuela's claim on British Guiana up to the Essequibo river (which had been settled by international arbitration half a century earlier, following the Venezuela Crisis of 1895) and he had all maps of Venezuela show this large territory as part of the country albeit as disputed.

Aligned with U.S. anticommunism policy Betancourt's firm stance against Castro, especially Cuba's expulsion from the Organization of American States (OAS) led to bloody military uprisings in 1962, first at Carúpano, then at Puerto Cabello. After the unsuccessful revolts, Betancourt suspended civil liberties and arrested the MIR and PCV members of the forerunner to the National Assembly of Venezuela bicameral Congress (Congreso) in 1962. This drove the leftists underground in the FALN, where they engaged in rural and urban guerrilla activities, including seized the Venezuelan cargo ship Anzoátegui, kidnapping Real Madrid soccer star Alfredo DiStefano, sabotaging oil pipelines of US companies, kidnaping of American Colonel Michael Smolen, bombing a Sears Roebuck warehouse, and bombing the United States Embassy in Caracas.

It was during the tense Cuban Missile Crisis, between the United States and Cuba, the relationship between President Kennedy and President Betancourt became closer than ever. Establishing a direct phone link between the White House and Miraflores (Presidential Palace) since the Venezuelan president had ample experience on dealing, defeating and surviving, actions of Caribbean-based pro-soviet regimes against pro-US regimes. FALN failed to rally the rural poor and to disrupt the December 1963 elections.

Venezuela asked the John F. Kennedy administration for the extradition of general Pérez Jiménez, and, to everyone's surprise, the USA complied, betraying an unconditional ally it had once bestowed with the Legion of Merit medal. Pérez Jiménez was first held in the Miami county jail and after an intense diplomatic dispute in 1963 was extradited to Venezuela on charges of embezzling $200 million during his presidential tenure related to Financiadora Administradora Inmobiliaria, S.A., one of the largest development companies in South America, and other business connections considered by academicians to be a classic study in the precedent for enforcement of administrative corruption in Latin American countries.[36] Upon arrival in Venezuela he was imprisoned until his trial, which did not take place for another five years. Convicted of the charges, his sentence was commuted as he had already spent more time in jail while he awaited trial. He was then exiled to Spain.

Rafael Caldera's first government emphasized the end of the Betancourt doctrine and broke the isolation of Venezuela with the rest of Latin America. With the new foreign policy of "ideological pluralism" and "pluralistic solidarity" for which it was diplomatically recognized military governments and cooperation between political regimes of different nature and ideology admitted (including Cuba), and made a policy in defense of the insular territories, and the Gulf of Venezuela, and signed the Port of Spain Protocol with Guyana, which concerned the Guayana Esequiba. The president's economic policies were notable for the reinforcement of the power of the entrepreneurs's association Fedecámaras, and the period of North American economic crisis, that also characterized the first term of Richard Nixon, with low oil prices, which caused the economic growth of Venezuela to stagnate. Caldera also presided over a period of pacification of the country, making a ceasefire with the left armed groups of FALN, which were then integrated into the political life, and legalising the Communist Party of Venezuela in spite of the opposition of Acción Democrática and US government. On June 3, 1970 was the first President of Venezuela that addressed a Joint Meeting of U.S. Congress with a speech in English language.

Presidency of Hugo Chávez

|

|---|

|

|

After Hugo Chávez was first elected President of Venezuela by a landslide in 1998, the South American country began to reassert sovereignty over its oil reserves, which challenged the comfortable position held by U.S. economic interests for the better part of a century. The Chávez administration overturned the privatization of the state-owned oil company PDVSA, raising royalties for foreign firms and eventually doubling the country's GDP.[37] Those oil revenues were used to fund social programs aimed at fostering human development in areas such as health, education, employment, housing, technology, culture, pensions, and access to safe drinking water.

Chávez's public friendship and significant trade relationship with Cuba and Fidel Castro undermined the U.S. policy of isolating Cuba, and long-running ties between the U.S. and Venezuelan militaries were severed on Chávez's initiative. During Venezuela's presidency of OPEC in 2000, Chávez made a ten-day tour of OPEC countries, in the process becoming the first head of state to meet Saddam Hussein since the Gulf War. The visit was controversial at home and in the U.S., although Chávez did respect the ban on international flights to and from Iraq (he drove from Iran, his previous stop).[38] In April 2002, under Carlos Ortega's leadership, the CTV declared a national strike, to protest what he felt were the "increasingly dictatorial" policies of President Hugo Chávez. In April 11's this culminated in a protest march to the Presidential Palace, Miraflores. After violence resulted in the death of 19 people, President Chávez was briefly removed from power by Pedro Carmona Estanga in a coup d'état.

Allegations of U.S. covert actions against Chávez government

After returning to power, Chávez claimed that a plane with U.S. registration numbers had visited and been berthed at Venezuela's Orchila Island airbase, where Chávez had been held captive.[citation needed] On May 14, 2002, Chávez alleged that he had definitive proof of U.S. military involvement in April 11's coup.[citation needed] He claimed that during the coup Venezuelan radar images had indicated the presence of U.S. military naval vessels and aircraft in Venezuelan waters and airspace. The Guardian published a claim by Wayne Madsen– a writer (at the time) for left-wing publications and a former Navy analyst and critic of the George W. Bush administration– alleging U.S. Navy involvement.[39] U.S. Senator Christopher Dodd, D-CT, requested an investigation of concerns that Washington appeared to condone the removal of Mr Chavez,[40][41] which subsequently found that "U.S. officials acted appropriately and did nothing to encourage an April coup against Venezuela's president", nor did they provide any naval logistical support.[42][43] According to Democracy Now!, CIA documents indicate that the Bush administration knew about a plot weeks before the April 2002 military coup. They cite a document dated April 6, 2002, which says: "dissident military factions...are stepping up efforts to organize a coup against President Chavez, possibly as early as this month."[citation needed] According to William Brownfield, ambassador to Venezuela, the U.S. embassy in Venezuela warned Chávez about a coup plot in April 2002.[44] Further, the United States Department of State and the investigation by the Office of the Inspector General found no evidence that "U.S. assistance programs in Venezuela, including those funded by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), were inconsistent with U.S. law or policy" or ". . . directly contributed, or was intended to contribute, to [the coup d'état]."[42][45]

Chávez also claimed, during the coup's immediate aftermath, that the U.S. was still seeking his overthrow. On October 6, 2002, he stated that he had foiled a new coup plot, and on October 20, 2002, he stated that he had barely escaped an assassination attempt while returning from a trip to Europe. However, his administration failed to investigate or present conclusive evidence to that effect. During that period, the US Ambassador to Venezuela warned the Chávez administration of two potential assassination plots.[44]

Venezuela expelled US naval commander John Correa in January 2006. The Venezuelan government claimed Correa, an attaché at the US embassy, had been collecting information from low-ranking Venezuelan military officers. Chavez claimed he had infiltrated the US embassy and found evidence of Correa's spying. The US declared these claims "baseless" and responded by expelling Jeny Figueredo, the chief aid to the Venezuelan ambassador to the US. Chavez promoted Figueredo to deputy foreign minister to Europe.[46]

Hugo Chávez repeatedly alleged that the US had a plan to invade Venezuela, a plan called Plan Balboa. In interview with Ted Koppel, Chavez stated "I have evidence that there are plans to invade Venezuela. Furthermore, we have documentation: how many bombers to overfly Venezuela on the day of the invasion, how many trans-Atlantic carriers, how many aircraft carriers..."[47] Neither President Chavez nor officials of his administration ever presented such evidence. The US denies the allegations, claiming that Plan Balboa is a military simulation carried out by Spain. [48]

On February 20, 2005, Chávez reported that the U.S. had plans to have him assassinated; he stated that any such attempt would result in an immediate cessation of U.S.-bound Venezuelan petroleum shipments.[49]

Economic relations

Chávez's socialist ideology and the tensions between the Venezuelan and the United States governments had little impact on economic relations between the two countries. While the volume of Venezuelan oil heading to the United States has declined since 2000 the only serious disruption came during the oil stoppage of 2002–2003, when production virtually ground to a halt as thousands of PDVSA officials went on strike to force Chavez's resignation. Chavez subsequently fired half of PDVSA's workforce, leading to a drain of talent many have blamed for some of the state company's operational. On September 15, 2005, President Bush designated Venezuela as a country that has "failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to their obligations under international counternarcotics agreements." However, at the same time, the President waived the economic sanctions that would normally accompany such a designation, because they would have curtailed his government's assistance for democracy programs in Venezuela.[50] In 2006, the United States remained Venezuela's most important trading partner for both oil exports and general imports – bilateral trade expanded 36% during that year[51]

With rising oil prices and Venezuela's oil exports accounting for the bulk of trade, bilateral trade between the US and Venezuela surged, with US companies and the Venezuelan government benefiting.[52] Nonetheless, since May 2006, the Department of State that, pursuant to Section 40A of the Arms Export Control Act, has prohibited the sale of defense articles and services to Venezuela because of lack of cooperation on anti-terrorism efforts.[53]

Opposition to U.S. foreign policy

After huge torrental rains and alluvions battered the coast of Venezuela in late 1999, Chávez initially accepted assistance from anyone who offered. The administration of president Bill Clinton sending helicopters and dozens of soldiers that arrived two days after the disaster. When defense minister Raúl Salazar complied with the offer of further aid that included 450 Marines and naval engineers aboard the USS Tortuga which was setting sail to Venezuela, Chávez told Salazar to decline the offer since "[i]t was a matter of sovereignty". Salazar became angry and assumed that Chávez's opinion was influenced by talks with Fidel Castro, though he complied with Chávez's order. Though additional aid was necessary, Chávez thought a more revolutionary image was more important and the USS Tortuga returned to its port.

Since the start of the George W. Bush administration in 2001, Chávez was highly critical of U.S. economic and foreign policy; he has critiqued U.S. policy with regards to Iraq, Haiti, Kosovo the Free Trade Area of the Americas, and other areas. Chávez also denounced the U.S.-backed ouster of Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in February 2004.[citation needed] In a speech at the United Nations General Assembly, Chávez said that Bush promoted "a false democracy of the elite" and a "democracy of bombs".[54]

Chávez's public friendship and significant trade relationship with Cuba and former Cuban President Fidel Castro undermined the U.S. policy of isolating Cuba. Longstanding ties between the US and Venezuelan militaries were also severed on Chávez's initiative. Chávez's stance as an OPEC price hawk has also raised the price of petroleum for American consumers, as Venezuela pushed OPEC producers towards lower production ceilings, with the resultant price settling around $25 a barrel prior to 2004. During Venezuela's holding of the OPEC presidency in 2000, Chávez made a ten-day tour of OPEC countries, in the process becoming the first head of state to meet Saddam Hussein since the Persian Gulf War. The visit was controversial at home and in the US, although Chávez did respect the ban on international flights to and from Iraq (he drove from Iran, his previous stop).[55]

The Bush administration consistently opposed Chávez's policies, and although it did not immediately recognize the Carmona government upon its installation during the 2002 attempted coup, it had funded groups behind the coup, speedily acknowledged the new government and seemed to hope it would last.[citation needed] The U.S. government called Chávez a "negative force" in the region, and sought support from among Venezuela's neighbors to isolate Chávez diplomatically and economically.[citation needed] One notable instance occurred at the 2005 meeting of the Organization of American States, a U.S. resolution to add a mechanism to monitor the nature of American democracies was widely seen as an attempt at diplomatically isolating both Chávez and the Venezuelan government. The failure of the resolution was seen by analysts as politically significant, evidencing widespread support in Latin America for Chávez, his policies, and his views.[citation needed]

The U.S. also opposed and lobbied against numerous Venezuelan arms purchases made under Chávez, including a purchase of some 100,000 rifles from Russia, which Donald Rumsfeld implied would be passed on to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and the purchase of aircraft from Brazil.[citation needed] The U.S. has also warned Israel to not carry through on a deal to upgrade Venezuela's aging fleet of F-16s, and has similarly pressured Spain.[citation needed] In August 2005, Chávez rescinded the rights of U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents to operate in Venezuelan territory, territorial airspace, and territorial waters. While U.S. State Department officials stated that the DEA agents' presence was intended to stem cocaine traffic from Colombia, Chávez argued that there was reason to believe the DEA agents were gathering intelligence for a clandestine assassination targeting him, with the ultimate aim of ending the Bolivarian Revolution.[citation needed]

When a Marxist insurgency picked up speed in Colombia in the early 2000s, Chavez chose not to support the U.S. in its backing of the Colombian government. Instead, Chavez declared Venezuela to be neutral in the dispute, yet another action that irritated American officials and tensed up relations between the two nations. The border between Venezuela and Colombia was one of the most dangerous borders in Latin America at the time, because of Colombia's war spilling over to Venezuela.[56]

Chávez dared the U.S. on March 14, 2008 to put Venezuela on a list of countries accused of supporting terrorism, calling it one more attempt by Washington, D.C. to undermine him for political reasons.[57]

In May 2011, Venezuela was one of the few countries to condemn the killing of Osama Bin Laden.[58]

Personal disputes

Chávez's anti-U.S. rhetoric sometimes touched the personal: in response to the ouster of Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in February 2004, Chávez called U.S. President George W. Bush a pendejo ("jerk" or "dumbass"); in a later speech, he made similar remarks regarding Condoleezza Rice. President Barack Obama called Chávez "a force that has interrupted progress in the region".[59] In a 2006 speech at the UN he referred to Bush as "the Devil" while speaking at the same podium the US president had used the previous day claiming that "it still smells of sulphur".[60] He later commented that Barack Obama "shared the same stench".[61]

During his weekly address Aló Presidente of March 18, 2006, Chávez responded to a US White House report which characterized him as a "demagogue who uses Venezuela's oil wealth to destabilize democracy in the region". During the address Chávez rhetorically called George W. Bush "a donkey." He repeated it several times adding "eres un cobarde ... eres un asesino, un genocida ... eres un borracho" (you are a coward ... you are an assassin, a mass-murderer ... you are a drunk).[62] Chávez said Bush was "a sick man" and "an alcoholic".[63]

Response to assassination calls

After prominent US evangelical Pat Robertson's on-air call for Chavez to be assassinated in August 2005, the Chávez administration reported that it would more closely scrutinize and curtail foreign evangelical missionary activity in Venezuela. Chávez himself denounced Robertson's call as a harbinger of a coming U.S. intervention to remove him from office. Chávez reported that Robertson, member of the secretive and elite Council for National Policy (CNP) – of which George Bush, Grover Norquist, and other prominent neoconservative Bush administration insiders were also known members or associates – was, along with other CNP members,[citation needed] guilty of "international terrorism". Robertson subsequently apologized for his remarks, which were criticised by Ted Haggard of the U.S.-based National Association of Evangelicals. Haggard was concerned about the effects Roberson's remarks would have on US corporate and evangelical missionaries' interests in Venezuela.

Relations with Cuba and Iran

Chávez's warm friendship with former Cuban president Fidel Castro, in addition to Venezuela's significant and expanding economic, social, and aid relationships with Cuba, undermined the U.S. policy objective seeking to isolate the island. President Chávez consolidated diplomatic relations with Iran, including defending its right to civilian nuclear power.[citation needed]

Organization of American States

At the 2005 meeting of the Organization of American States, a United States resolution to add a mechanism to monitor the nature of democracies was widely seen as a move to isolate Venezuela. The failure of the resolution was seen as politically significant, expressing Latin American support for Chávez.[64]

Hurricane Katrina

After Hurricane Katrina battered the United States' Gulf coast in late 2005, the Chávez administration offered aid to the region.[65] Chávez offered tons of food, water, and a million barrels of extra petroleum to the U.S. He has also proposed to sell, at a significant discount, as many as 66,000 barrels (10,500 m3) of fuel oil to poor communities that were hit by the hurricane, and offered mobile hospital units, medical specialists, and electrical generators. The Bush administration declined the Venezuelan offer according to activist Jesse Jackson,[66] but United States Ambassador to Venezuela William Brownfield welcomed the offer of fuel assistance to the region, calling it "a generous offer" and saying "When we are talking about one-to-five million dollars, that is real money. I want to recognize that and say, 'thank you.'"[67]

Following negotiations by leading US politicians for the US' largest fuel distributors to offer discounts to the less well-off, in November 2005, officials in Massachusetts signed an agreement with Venezuela to provide heating oil at a 40% discount to low income families through Citgo, a subsidiary of PDVSA and the only company to respond to the politicians' request.[68] Chávez stated that such gestures comprise "a strong oil card to play on the geopolitical stage" and that "it is a card that we are going to play with toughness against the toughest country in the world, the United States."[69]

Relations breakdown

The reactivation of the Fourth Fleet without first informing foreign governments in the region sparked concern within some South American governments. The governments of Argentina and Brazil made formal inquiries as to the fleet's mission in the region. In Venezuela, President Hugo Chávez accused the United States of attempting to frighten the people of South America by reactivating the fleet.[70] and vowed that his country's new Sukhoi Su-30 jets could sink any U.S. ships invading Venezuelan waters. Cuban ex-president Fidel Castro warned that it could lead to more incidents such as the 2008 Andean diplomatic crisis.[71] In September 2008, following retaliatory measures in support of Bolivia, Chavez expelled the U.S. ambassador Patrick Duddy, labeling him persona non grata after accusing him of aiding a conspiracy against his government – a charge Duddy consequently denied.[72]

Despite allegedly waning of Hugo Chavez's aggressive foreign policy due to the sharp drop in oil in the last quarter of 2008, hostility with America continued. "American Corners," (AC) a partnership between the Public Affairs sections of U.S. Embassies worldwide and their host institutions, was said to be an interference in Venezuela. Eva Golinger and the Frenchman Roman Mingus, in their book, Imperial Spiderweb: Encyclopedia of Interference and Subversion, warned that it was one of Washington's secret forms of propaganda, with Golinger denouncing AC to the Venezuelan National Assembly as virtual consulates which are not formally sponsored by the US government but by an organization, association, school, library or local institution, which have not only functioned as a launch pad for a psychological war but also sought to subvert and violate diplomatic rules. The AC's were alleged to be closely supervised by the State Department.[73] Golinger has been described by many[74][75][76][77][78] as pro-Chavez.

In January 2009 Chavez announced an investigation into the US Chargé d'Affairs, John Caulfield, who is the leading US diplomat after Duddy's expulsion. He contended that Caulfield possibly had met with opposition Venezuelans in exile in Puerto Rico; an official spokeswoman from the United States said Caulfield was there for a wedding. Chavez used the occasion to accuse "the empire" of using Puerto Rico as a base for actions against him and Latin America. He referred to Puerto Rico as a "gringo colony" and that one day the island would be liberated.[79]

Presidency of Barack Obama

During the 2008 U.S. election Chávez declared that he had no preference between Barack Obama and John McCain stating "the two candidates for the US presidency attack us equally, they attack us defending the interests of the empire".[80] After Obama had won the election, Venezuela's foreign minister labeled the outcome a historic moment in international relations, and added that the American people had chosen a "new brand" of diplomacy. Asked if the previously expelled ambassadors for each country would return, he replied "everything has its time."[citation needed] However at a rally the evening before November 4 elections where Chávez was supporting his own candidates Chávez echoed a sentiment by the president of Brazil Lula da Silva and Evo Morales president of Bolivia where the change happening in Latin America seemed to be taking place in the US. He expressed hope that he would meet with Obama as soon as possible.[72] However, on March 22, 2009 Chávez called Obama "ignorant" and claimed Obama "has the same stench as Bush", after the US accused Venezuela of supporting the insurgent Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia.[81] Chávez was offended after Obama said that he had "been a force that has interrupted progress in the region", resulting in his decision to put Venezuela's new ambassador to the United States on hold.[82]

During the Summit of the Americas on April 17, 2009, Chávez met with Obama for the first, and only, time where he expressed his wish to become Obama's friend.[83][84]

On September 10, 2009, Chávez gave a speech at the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia in Moscow declaring that "in all history, there was never a government more terrorist than that of the US empire. That's the greatest terrorists in the world history," , adding that the "Yankee empire will fall. It's already falling, and will disappear from the face of the Earth, and it's going to happen this century."[85]

On December 20, 2011, Chávez called Obama "A clown, an embarrassment, and a shame to Black People" after Obama criticized Venezuela's ties with Iran and Cuba.[86]

Venezuela and the United States have not had ambassadors in each other's capitals since 2010.[87] Shortly before the 2012 US presidential elections, Chávez announced that if he could vote in the election, he would vote for Obama.[88]

Allegations of U.S. Involvement in Chávez' Death

In December 2011, Chávez, already under treatment for cancer, wondered out loud: “Would it be so strange that they’ve invented the technology to spread cancer and we won’t know about it for 50 years?” The Venezuelan president was speaking one day after Argentina’s leftist president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, announced she had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. This was after three other prominent leftist Latin America leaders had been diagnosed with cancer: Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff; Paraguay's Fernando Lugo; and the former Brazilian leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. However, days after that, Chávez said that it was just a joke. While many people believe in the conspiracy, in the Oliver Stone documentary Mi amigo Hugo (made one year after Chávez' death), various presidents (included Maduro and those mentioned above) and Venezuela government people said that "even him will reject the idea of somebody causing his death". The Guardian newspaper's Venezuela expert Rory Carroll has glibly categorized serious charges that Venezuela's late President Hugo Chavez Frias was assassinated by a United States-produced bio-weapon as being in the same league with "conspiracy theorists who wonder about aliens at Roswell and NASA faking the moon landings". A number of Venezuelan officials[89] believe a hostile party covertly introduced an aggressive form of cancer into the 58-year-old president.

Presidency of Nicolás Maduro

In 2013, before Hugo Chavez died Venezuelan Vice President Nicolas Maduro expelled two U.S. military attaches from the country saying they were plotting against Venezuela, by attempting to recruit Venezuelan military personnel to destabilize Venezuela, and suggested they caused Chavez's cancer.[90] The Obama Administration rejected the allegations, and responded by expelling two Venezuelan diplomats.[91]

On October 1, 2013, the U.S ordered three Venezuelan diplomats out of the country in response to the Venezuelan government's decision to expel three U.S. officials from Venezuela.[92]

On February 16, 2014 President Maduro announced he had ordered another three U.S. consular officials leave the country, accusing them of conspiring against the government and aiding opposition protests. In response to a U.S. statement that it was concerned over rising tensions and protests, and warning against Venezuela's possible arrest of the country's opposition leader, Maduro described the U.S. comments as "unacceptable" and "insolent." He said "I don't take orders from anyone in the world."[93] On February 25, 2014, the United States responded by expelling three additional Venezuelan diplomats from the country.[94]

On May 28, 2014, the United States House of Representatives passed the Venezuelan Human Rights and Democracy Protection Act, a bill that would apply economic sanctions against Venezuelan officials who were involved in the mistreatment of protestors during the 2014 Venezuelan protests.[95]

In December 2014, the US Congress passed Senate 2142 (the "Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014")[96]

On March 9, 2015, the United States president, Barack Obama signed and issued a presidential order declaring Venezuela a threat to its national security and ordered sanctions against seven Venezuelan officials. Venezuelan president, Maduro, denounced the sanctions as an attempt to topple his socialist government. Washington said that the sanctions targeted individuals who were involved in the violation of Venezuelans' human rights, saying that "we are deeply concerned by the Venezuelan government's efforts to escalate intimidation of its political opponents".[97]

The move was widely denounced by other Latin American countries. The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States issued a statement criticizing Washington's "unilateral coercive measures against International Law."[98] The Secretary-General of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), Ernesto Samper said that the body rejects "any attempt at internal or external interference that attempts to disrupt the democratic process in Venezuela."[99]

United States–Venezuela views

United States

Despite the continually strained ties between the two governments, 82% of Venezuelans viewed the U.S. positively in 2002, though this view declined down to 62% in 2014 (per the Pew Research Global Attitudes Project).[100] The Gallup Global Leadership Report indicates that as of 2013, 35% of Venezuelans approve of United States' global leadership, and 35% disapprove.[101]

SICOFAA

In 1960 the UNITAS naval exercises and in port training involving several countries in North, South and Central America were conducted by first time in Venezuelan territorial waters in support of the Cold war U.S. policy. Venezuela is an active member of SICOFAA.

Images

See also

- United States and South and Central America

- Foreign policy of the United States

- United States – Venezuela Maritime Boundary Treaty

- Venezuelan American

- Bolivarian diaspora

- List of authoritarian regimes supported by the United States

Notes

- ^ Sometimes called the "first Venezuelan crisis", the crisis of 1902–03 being the second.

References

- ^ "Venezuela expels 3 American Diplomats over Violence Conspiracy". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Bulletin of the Pan American Union, vol. XXXVI (1913), p. 760

- ^ John Quincy Adams (1875). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. J.B. Lippincott & Company. p. 75.

- ^ Natalie Ornish (September 1, 2011). Pioneer Jewish Texans. Texas A&M University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-60344-433-0.

- ^ David G. McComb (January 1, 2010). Galveston: A History. University of Texas Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-292-79321-7.

- ^ Frank L. Owsley; Gene A. Smith (March 22, 2004). Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800–1821. University of Alabama Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8173-5117-5.

- ^ James L. Erwin (2007). Declarations of Independence: Encyclopedia of American Autonomous and Secessionist Movements. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-313-33267-8.

- ^ David Head (October 1, 2015). Privateers of the Americas: Spanish American Privateering from the United States in the Early Republic. University of Georgia Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8203-4400-3.

- ^ Judith Ewell (1996). Venezuela and the United States: From Monroe's Hemisphere to Petroleum's Empire. University of Georgia Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8203-1782-3.

- ^ Rafe Blaufarb (2005). Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815–1835. University of Alabama Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8173-1487-3.

- ^ Richard G. Lowe (July 1966). "American Seizure of Amelia Island". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 45 (1): 22. JSTOR 30145698.

- ^ British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. 1837. pp. 756–757.

- ^ "Panama: A Country Study". Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1987.

- ^ History of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, p.60, 2005

- ^ King (2007:249)

- ^ a b Graff, Henry F., Grover Cleveland (2002). ISBN 0-8050-6923-2. pp123-25

- ^ Ferrell, Robert H. "Monroe Doctrine". ap.grolier.com. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Hendrickson, Embrert (August 1970). "Roosevelt's Second Venezuelan Controversy". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 50 (3): 482–498. doi:10.2307/2512193. See p. 483.

- ^ Judith Ewell. "Venezuela y los Estados Unidos: desde el hemisferio de Monroe al imperio del Petroleo" p. 136

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Coronelwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Yergin, p. 435

- ^ Jose Toro-Hardy (1994). Oil: Venezuela and the Persian Gulf. Editorial Panapo.

- ^ Daniel Yergin (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- ^ Alliances, Coalitions, and Ententes – The American alliance system: an unamerican tradition

- ^ "B-29: INTER-AMERICAN TREATY OF RECIPROCAL ASSISTANCE (RIO TREATY)". Organization of American States. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Cohen, Rich (2012). The Fish that Ate the Whale. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 186.

- ^ Ayala, Cesar J (1999). American Sugar Kingdom. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Adolf A. Berle, Jr., "Latin America: The Hidden Revolution," Reporter, May 28, 1959.

- ^ Time, August 23, 1963, as cited in John Gunther, Inside South America, p. 492-493

- ^ 13 May 1958: Nixon attacked by angry Venezuelans, history.com.

- ^ http://www.monografias.com/trabajos5/econvenez/econvenez3.shtml

- ^ Manchester, William (1984). The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34589-3.

- ^ Marius Vassiliou (March 2, 2009). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. Scarecrow Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-8108-6288-3. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ https://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/Archives/USG-01-A.aspx

- ^ "The Extradition of Marcos Perez Jimenez, 1959–63: Practical Precedent for Administrative Honesty?", Judith Ewell, Journal of Latin American Studies, 9, 2, 291–313, [1]

- ^ CEPR – The Chávez Administration at 10 Years – February 2009

- ^ – Chavez's tour of OPEC nations arrives in Baghdad. CNN.com. August 10, 2000

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (April 29, 2006). "American navy 'helped Venezuelan coup'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 21, 2006.

- ^ "US investigates Venezuela coup role". BBC News. May 14, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2006.

- ^ "Venezuela's Chavez Says United States Must Explain Reaction To Coup". May 10, 2002. Archived from the original on June 21, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b U.S. Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela. State Dept. Issues Report on U.S. Actions During Venezuelan Coup: (Inspector General finds U.S. officials acted properly during coup). Archived October 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 26, 2006.

- ^ U.S. Department of State and Office of Inspector General. A Review of U.S. Policy toward Venezuela, November 2001 – April 2002. Archived April 23, 2003, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 26, 2006.

- ^ a b Márquez Humberto. (IPS March 9, 2006) "Statements Indicate Chávez May Indeed Be in Somebody's Crosshairs". Archived July 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 21, 2006.

- ^ CIA Documents Show Bush Knew of 2002 Coup in Venezuela.. Democracy Now, November 29, 2004. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ Chavez promotes expelled diplomat BBC NEWS

- ^ "Transcript: Hugo Chavez Interview". ABC News. September 16, 2005. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ^ "'Plan Balboa' Not a U.S. Plan To Invade Venezuela" Archived February 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chavez says US plans to kill him. BBC News (February 21, 2005). Retrieved July 1, 2006.

- ^ Sullivan, Mark P. (August 1, 2008) "Venezuela: Political Conditions and U.S. Policy", page 35. United States Congressional Research Service

- ^ "Synergy with the Devil", James Surowiecki, The New Yorker, January 8, 2006.

- ^ "For Venezuela, as Distaste for U.S. Grows, So Does Trade" New York Times

- ^ Sullivan, Mark P. (August 1, 2008) "Venezuela: Political Conditions and U.S. Policy" United States Congressional Research Service, page 1, 37

- ^ Chavez tells UN Bush is 'devil', BBC

- ^ Chavez's tour of OPEC nations arrives in Baghdad, Venezuelan president first head of state to visit Hussein in 10 years. CNN (August 10, 2000). Retrieved July 1, 2006.

- ^ Encarnación, Omar (2002). "Venezuela's "Civil Society Coup"". World Policy Journal. JSTOR 40209803.

- ^ Venezuela dares U.S. to put it on terror list CNN (March 14, 2008). Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ Venezuela VP slams bin Laden ‘murder’, Washington Times. May 2, 2011. "It surprises me to no end how natural crime and murder has become, how it is celebrated. At least before, imperialist governments were more subtle. Now the death of anyone, based on what they are accused of, but not only those working outside of the law like bin Laden, but also presidents, the families of presidents, are openly celebrated by the leaders of the nations that bomb them."

- ^ Staff Writer. "Article 106 of the constitution is clear". Stabroek News. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Chavez tells UN Bush is 'devil'". BBC News. September 20, 2006.

- ^ Forero, Juan (January 19, 2009). "Obama and Chávez Start Sparring Early". The Washington Post.

- ^ Telegraph. Bush a donkey and drunkard, says Chavez.. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ "Chavez Boosts Heating Oil Program for U.S. Poor; Goes After Bush Again", Washington Post

- ^ Brinkley, Joel (June 6, 2005). "Latin Nations Resist Plan for Monitor of Democracy". New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ USA Today: Venezuela's Chavez offers hurricane aid. September 1, 2005.

- ^ (September 6, 2005). "Bush rejects Chávez aid". The Guardian. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Voice of America: US Ambassador: Venezuelan Post-Katrina Aid Welcome. Accessed March 13, 2014.

- ^ BBC News. (November 23, 2005). "Venezuela gives US cheap oil deal". Retrieved November 23, 2005.

- ^ Blum, Justin (November 22, 2005). "Chavez Pushes Petro-Diplomacy". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 29, 2005.

- ^ "Chavez attacks the Fourth Fleet at the start of parade / Chávez arremete contra la IV Flota en el inicio del desfile militar". www.noticias24.com. July 5, 2008.

- ^ "Fourth Fleet to intervene to Latin America tomorrow / IV Flota de intervención hacia Latinoamérica mañana". www.rlp.com.ni. June 30, 2008.

- ^ a b http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/11/06/news/LT-Venezuela-US-Obama.php

- ^ "Venezuela Condemns US Interference". Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Romero, Simon, (October 26, 2009). "Michael Moore Irks Supporters of Chávez". New York Times

- ^ Golinger, Eva (January 10, 2010). Eva Golinger Describes Curacao as the Third Frontier of the United States. Salem-News.com. Retrieved February 22, 2010

- ^ Bogardus, Keven (September 22, 2004). Venezuela Head Polishes Image With Oil Dollars: President Hugo Chavez takes his case to America's streets. Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Bart (April 2, 2004). "U.S. funds aid Chavez opposition: National Endowment for Democracy at center of dispute in Venezuela". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Forero, Juan (December 3, 2004). "Documents Show C.I.A. Knew of a Coup Plot in Venezuela". The New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ http://www.elnuevodia.com/diario/noticia/mundiales/noticias/chavez:_puerto_rico_es_colonia_gringa_todavia/516443

- ^ Tran, Mark (July 17, 2008). "Obama no different to McCain, says Chavez". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Forero, Juan (January 19, 2009). "Obama and Chávez Start Sparring Early". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1237727509556&pagename=JPost/JPArticle/ShowFull

- ^ "Obama Says U.S. Will Pursue Thaw With Cuba". The New York Times. April 18, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Obama: 'We can move U.S.-Cuban relations in a new direction'". CNN. April 17, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ http://www.russiatoday.com/Top_News/2009-09-10/chavez-russia-emotional-speech.html

- ^ "Chavez: Obama's a 'clown' president". POLITICO. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Venezuela to investigate Chavez murder allegations". BBC News. March 12, 2013.

- ^ Cline, Seth (October 1, 2012). "Hugo Chavez Says He Would Vote for Obama". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "Venezuela says embalming of Chavez' body 'unlikely'". bbc.co.uk/news. March 13, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Ezequiel Minaya; David Luhnow (March 5, 2013). "Venezuela Takes Page From Cuban Playbook". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

"Venezuela expels two U.S. military attachesdenouncing U.S. conspiratorial plan". Xinhua. March 6, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

Karen DeYoung (March 11, 2013). "U.S. seeks better relations with Venezuela, but says they may not come soon". Washington Post. Retrieved March 11, 2013. - ^ "Obama, US lawmakers see 'new chapter' in Venezuela after Chavez's death". Fox News. March 6, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

Vice President Nicolas Maduro claimed "historical enemies" of Venezuela were behind Chavez's cancer diagnosis. The Venezuelan government also expelled two U.S. diplomats from the country – accusing them of spying.

The State Department rejected the allegations and suggested it did not bode well for the future of U.S.-Venezuela ties.

William Neuman (March 11, 2013). "U.S. Expels 2 Venezuela Envoys". New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

"Venezuela diplomats expelled by US in tit-for-tat row". BBC News. March 11, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

Bradley Klapper (March 11, 2013). "In retaliation, U.S. boots Venezuelan diplomats". Army Times. Associated Pres. Retrieved March 12, 2013. - ^ "Venezuelan diplomats expelled by U.S. in retaliation". USA Today. October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ "Expulsion of three US envoys ordered by Venezuela". Venezuela Star. February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ "U.S. expelling 3 Venezuelan diplomats". USA Today. February 25, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ Marcos, Cristina (May 28, 2014). "House passes Venezuela sanctions bill". The Hill. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ Jonathan C. Poling, Akin Gump, http://www.akingump.com/en/news-insights/obama-to-sign-venezuela-sanctions-bill.html

- ^ "U.S. declares Venezuela a national security threat, sanctions top officials". Reuters. March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Aditya Tejas (March 13, 2015). "Venezuela President Nicolas Maduro Granted Special Powers Designed To Counter 'Imperialism'". ibtimes. International Business Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ "'Undemocratic, interventionist': Bolivia lashes out at Obama for Venezuela sanctions". RT. March 13, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Favorable Opinion of the United States Pew Research Center

- ^ "U.S. Global Leadership Report". Report. Gallup. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

Further reading

- Ewell, Judith. Venezuela and the United States: From Monroe's Hemisphere to Petroleum's Empire (University of Georgia Press, 1996)