Individualist anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Individualism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems.[1][2] Although usually contrasted to social anarchism, both individualist and social anarchism have influenced each other. Mutualism, an economic theory particularly influential within individualist anarchism whose pursued liberty has been called the synthesis of communism and property,[3] has been considered sometimes part of individualist anarchism[4][5][6] and other times part of social anarchism.[7][8] Many anarcho-communists regard themselves as radical individualists,[9] seeing anarcho-communism as the best social system for the realization of individual freedom.[10] Economically, while European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most American individualist anarchists advocate mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics.[11] Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that gives privilege and is exploitative,[12] seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital – that is, of property" by mutual credit.[13]

Individualist anarchism represents a group of several traditions of thought and individualist philosophies within the anarchist movement. Among the early influences on individualist anarchism were William Godwin (philosophical anarchism),[14] Josiah Warren (sovereignty of the individual), Max Stirner (egoism),[15] Lysander Spooner (natural law), Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (mutualism), Henry David Thoreau (transcendentalism),[16] Herbert Spencer (law of equal liberty)[17] and Anselme Bellegarrigue (civil disobedience).[18] From there, individualist anarchism expanded through Europe and the United States, where prominent 19th-century individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker held that "if the individual has the right to govern himself, all external government is tyranny".[19]

Within anarchism, individualist anarchism is primarily a literary phenomenon[20] while social anarchism has been the dominant form of anarchism,[21][22][23][24] emerging in the late 19th century as a distinction from individualist anarchism after anarcho-communism replaced collectivist anarchism as the dominant tendency.[25] Individualist anarchism has been described by some as the anarchist branch most influenced by and tied to liberalism (the classical liberalism deriving anti-capitalist notions and socialist economics from classical political economists and the labor theory of value) as well as being described as a part of the liberal or liberal-socialist wing – in contrast to the collectivist or communist wing – of anarchism and libertarian socialism.[26][27][28] However most do not agree with this divide. Social anarchists including collectivist and communist anarchists regard the individualist anarchists as socialists and libertarian socialists due to their opposition to capitalist profit, interest, and absentee rent.[29] The very idea of an individualist–socialist divide is also contested as individualist anarchism is largely socialistic[30][31][32] and can be considered a form of individualist socialism, with non-Lockean individualism encompassing socialism.[33] Individualist anarchism is the basis of most anarchist schools of thought, influencing nearly all anarchist tendencies and having contributed to much of anarchist discourse.[34][35]

While anarcho-capitalism is sometimes described as a form of individualist anarchism,[36][37][38][39][40] many others disagree with this as individualist anarchism is largely socialistic.[32][41] Murray Rothbard, the founder of anarcho-capitalism, argued that individualist anarchism is different from anarcho-capitalism and other capitalist theories due to the individualist anarchists retaining the labor theory of value and socialist economics.[42]

Overview

|

Other names that have been used to refer to individualist anarchism include:

|

The term individualist anarchism is often used as a classificatory term, but in very different ways. Some such as the authors of An Anarchist FAQ use the classification individualist anarchism/social anarchism.[11] Others such as Geoffrey Ostergaard, who see individualist anarchism as distinctly non-socialist, recognizing anarcho-capitalist as part of the individualist anarchist tradition, use the classification individualist anarchism/socialist anarchism accordingly.[36] However most do not consider anarcho-capitalism as part of the anarchist movement because anarchism has historically been an anti-capitalist movement and anarchists reject that it is compatible with capitalism.[43][44][45][46][47][48] In addition, an analysis of individualist anarchists who advocated free-market anarchism shows that it is different from anarcho-capitalism and other capitalist theories due to the individualist anarchists retaining the labor theory of value and socialist doctrines.[49][32][50] Other classifications include communal/mutualist anarchism.[51] Michael Freeden identifies four broad types of individualist anarchism. Freeden says the first is the type associated with William Godwin that advocates self-government with a "progressive rationalism that included benevolence to others". The second type is the amoral self-serving rationality of egoism as most associated with Max Stirner. The third type is "found in Herbert Spencer's early predictions, and in that of some of his disciples such as Wordsworth Donisthorpe, foreseeing the redundancy of the state in the source of social evolution". The fourth type retains a moderated form of egoism and accounts for social cooperation through the advocacy of market relationships.[17] Individualist anarchism of different kinds have the following things in common:

- The concentration on the individual and their will in preference to any construction such as morality, ideology, social custom, religion, metaphysics, ideas or the will of others.[52][53]

- The rejection of or reservations about the idea of revolution, seeing it as a time of mass uprising which could bring about new hierarchies. Instead, they favor more evolutionary methods of bringing about anarchy through alternative experiences and experiments and education which could be brought about today.[54][55] This is also because it is not seen as desirable for individuals to wait for revolution to start experiencing alternative experiences outside what is offered in the current social system.[56]

- Individual experience and exploration is emphasized. The view that relationships with other persons or things can be in one's own interest only and can be as transitory and without compromises as desired since in individualist anarchism sacrifice is usually rejected. In this way, Max Stirner recommended associations of egoists.[57][58]

Individualists anarchists considered themselves to be socialists and part of the socialist movement which according to those anarchists was divided in two wings, namely anarchist socialism and state socialism.[59][60] Benjamin Tucker criticized those who were trying to exclude individualist anarchism from socialism based on dictionary's definitions.[61] Tucker held that the mutualist title to land and other scarce resources would involve a radical change and restriction of capitalist property rights.[12][62][63] It should also be noted social anarchists including collectivist and communist anarchists regard the individualist anarchists as socialists due to their opposition to surplus-value something even Karl Marx (whom Tucker was influenced by [64]) would agree is anti-capitalist.[29][65]

Individualist anarchists such as Tucker argued that it was "not Socialist Anarchism against Individualist Anarchism, but of Communist Socialism against Individualist Socialism".[66] Tucker further noted that "the fact that State Socialism has overshadowed other forms of Socialism gives it no right to a monopoly of the Socialistic idea".[67] In 1888, Tucker, who proclaimed himself to be an anarchistic socialist in opposition to state socialism, included the full text of a "Socialistic Letter" by Ernest Lesigne in his essay "State Socialism and Anarchism".[68] According to Lesigne, there are two socialisms: "One is dictatorial, the other libertarian".[69] Tucker's two socialisms were the state socialism which he associated to the Marxist school and the libertarian socialism that he advocated. What those two schools of socialism had in common was the labor theory of value and the ends, by which anarchism pursued different means.[70]

According to Rudolf Rocker, individualist anarchists "all agree on the point that man be given the full reward of his labour and recognised in this right the economic basis of all personal liberty. They regard free competition [...] as something inherent in human nature. [...] They answered the socialists of other schools who saw in free competition one of the destructive elements of capitalistic society that the evil lies in the fact that today we have too little rather than too much competition".[12] Individualist anarchist Joseph Labadie wrote that both "the two great sub-divisions of Socialists [Anarchists and State Socialists] agree that the resources of nature – land, mines, and so forth – should not be held as private property and subject to being held by the individual for speculative purposes, that use of these things shall be the only valid title, and that each person has an equal right to the use of all these things. They all agree that the present social system is one composed of a class of slaves and a class of masters, and that justice is impossible under such conditions".[12] The egoist form of individualist anarchism, derived from the philosophy of Max Stirner, supports the individual doing exactly what he pleases – taking no notice of God, state, or moral rules.[71] To Stirner, rights were spooks in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the individuals are its reality" – he supported property by force of might rather than moral right.[72] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw "associations of egoists" drawn together by respect for each other's ruthlessness.[73]

For historian Eunice Minette Schuster, American individualist anarchism "stresses the isolation of the individual – his right to his own tools, his mind, his body, and to the products of his labor. To the artist who embraces this philosophy it is "aesthetic" anarchism, to the reformer, ethical anarchism, to the independent mechanic, economic anarchism. The former is concerned with philosophy, the latter with practical demonstration. The economic anarchist is concerned with constructing a society on the basis of anarchism. Economically he sees no harm whatever in the private possession of what the individual produces by his own labor, but only so much and no more. The aesthetic and ethical type found expression in the transcendentalism, humanitarianism, and Romanticism of the first part of the nineteenth century, the economic type in the pioneer life of the West during the same period, but more favorably after the Civil War".[74]

For this reason, it has been suggested that in order to understand individualist anarchism one must take into account "the social context of their ideas, namely the transformation of America from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist society [...] the non-capitalist nature of the early U.S. can be seen from the early dominance of self-employment (artisan and peasant production). At the beginning of the 19th century, around 80% of the working (non-slave) male population were self-employed. The great majority of Americans during this time were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs" and "[i]ndividualist anarchism is clearly a form of artisanal socialism [...] while communist anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism are forms of industrial (or proletarian) socialism".[75]

Liberty insisted on "the abolition of the State and the abolition of usury; on no more government of man by man, and no more exploitation of man by man"[76] and anarchism is "the abolition of the State and the abolition of usury".[77] Those anarchists held that there were "two schools of Socialistic thought, [...] State Socialism and Anarchism" and "liberty insists on Socialism [...] – true Socialism, Anarchistic Socialism: the prevalence on earth of Liberty, Equality, and Solidarity". Individualist anarchists followed Proudhon and other anarchists that "exploitation of man by man and the domination of man over man are inseparable, and each is the condition of the other", that "the bottom claim of Socialism" was "that labour should be put in possession of its own", that "the natural wage of labour is its product" in an "effort to abolish the exploitation of labour by capital" and that anarchists "do not admit the government of man by man any more than the exploitation of man by man", advocating "the complete destruction of the domination and exploitation of man by man".[12] Contemporary individualist anarchist Kevin Carson characterizes American individualist anarchism by saying that "[u]nlike the rest of the socialist movement, the individualist anarchists believed that the natural wage of labor in a free market was its product, and that economic exploitation could only take place when capitalists and landlords harnessed the power of the state in their interests. Thus, individualist anarchism was an alternative both to the increasing statism of the mainstream socialist movement, and to a classical liberal movement that was moving toward a mere apologetic for the power of big business".[78]

In European individualist anarchism, a different social context helped the rise of European individualist illegalism and as such "[t]he illegalists were proletarians who had nothing to sell but their labour power, and nothing to discard but their dignity; if they disdained waged-work, it was because of its compulsive nature. If they turned to illegality it was due to the fact that honest toil only benefited the employers and often entailed a complete loss of dignity, while any complaints resulted in the sack; to avoid starvation through lack of work it was necessary to beg or steal, and to avoid conscription into the army many of them had to go on the run".[79] A European tendency of individualist anarchism advocated violent individual acts of individual reclamation, propaganda by the deed and criticism of organization. Such individualist anarchist tendencies include French illegalism[80][81] and Italian anti-organizational insurrectionarism.[82] Bookchin reports that at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th "it was in times of severe social repression and deadening social quiescence that individualist anarchists came to the foreground of libertarian activity – and then primarily as terrorists. In France, Spain, and the United States, individualistic anarchists committed acts of terrorism that gave anarchism its reputation as a violently sinister conspiracy".[83]

Another important tendency within individualist anarchist currents emphasizes individual subjective exploration and defiance of social conventions. Individualist anarchist philosophy attracted "amongst artists, intellectuals and the well-read, urban middle classes in general".[79] Murray Bookchin describes a lot of individualist anarchism as people who "expressed their opposition in uniquely personal forms, especially in fiery tracts, outrageous behavior and aberrant lifestyles in the cultural ghettos of fin de siecle New York, Paris and London. As a credo, individualist anarchism remained largely a bohemian lifestyle, most conspicuous in its demands for sexual freedom ('free love') and enamored of innovations in art, behavior, and clothing".[84] In this way, free love[85][86] currents and other radical lifestyles such as naturism[86][87] had popularity among individualist anarchists.

For Catalan historian Xavier Diez, "under its iconoclastic, antiintelectual, antitheist run, which goes against all sacralized ideas or values it entailed, a philosophy of life which could be considered a reaction against the sacred gods of capitalist society. Against the idea of nation, it opposed its internationalism. Against the exaltation of authority embodied in the military institution, it opposed its antimilitarism. Against the concept of industrial civilization, it opposed its naturist vision".[88] In regards to economic questions, there are diverse positions. There are adherents to mutualism (Proudhon, Émile Armand and the early Tucker), egoistic disrespect for "ghosts" such as private property and markets (Stirner, John Henry Mackay, Lev Chernyi and the later Tucker) and adherents to anarcho-communism (Albert Libertad, illegalism and Renzo Novatore).[89] Anarchist historian George Woodcock finds a tendency in individualist anarchism of a "distrust (of) all co-operation beyond the barest minimum for an ascetic life".[90] On the issue of violence opinions have gone from a violentist point of view mainly exemplified by illegalism and insurrectionary anarchism to one that can be called anarcho-pacifist. In the particular case of Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Giménez Igualada, he went from illegalist practice in his youth[91] towards a pacifist position later in his life.[92]

Early influences

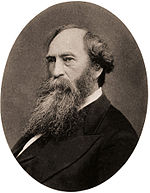

William Godwin

William Godwin can be considered an individualist anarchist[93] and philosophical anarchist who was influenced by the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[94] and developed what many consider the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[14] According to Peter Kropotkin, Godwin was "the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his work".[95] Godwin himself attributed the first anarchist writing to Edmund Burke's A Vindication of Natural Society.[96] Godwin advocated extreme individualism, proposing that all cooperation in labor be eliminated.[97] Godwin was a utilitarian who believed that all individuals are not of equal value, with some of us "of more worth and importance" than others depending on our utility in bringing about social good. Therefore, he does not believe in equal rights, but the person's life that should be favored that is most conducive to the general good.[98] Godwin opposed government because it infringes on the individual's right to "private judgement" to determine which actions most maximize utility, but also makes a critique of all authority over the individual's judgement. This aspect of Godwin's philosophy, minus the utilitarianism, was developed into a more extreme form later by Stirner.[99]

Godwin took individualism to the radical extent of opposing individuals performing together in orchestras, writing in Political Justice that "everything understood by the term co-operation is in some sense an evil".[97] The only apparent exception to this opposition to cooperation is the spontaneous association that may arise when a society is threatened by violent force. One reason he opposed cooperation is he believed it to interfere with an individual's ability to be benevolent for the greater good. Godwin opposes the idea of government, but wrote that a minimal state as a present "necessary evil"[100] that would become increasingly irrelevant and powerless by the gradual spread of knowledge.[14] He believed democracy to be preferable to other forms of government.[101]

Godwin supported individual ownership of property, defining it as "the empire to which every man is entitled over the produce of his own industry".[100] However, he also advocated that individuals give to each other their surplus property on the occasion that others have a need for it, without involving trade (e.g. gift economy). Thus while people have the right to private property, they should give it away as enlightened altruists. This was to be based on utilitarian principles and he said: "Every man has a right to that, the exclusive possession of which being awarded to him, a greater sum of benefit or pleasure will result than could have arisen from its being otherwise appropriated".[100]

Godwin's political views were diverse and do not perfectly agree with any of the ideologies that claim his influence as writers of the Socialist Standard, organ of the Socialist Party of Great Britain, consider Godwin both an individualist and a communist;[102] Murray Rothbard did not regard Godwin as being in the individualist camp at all, referring to him as the "founder of communist anarchism";[103] and historian Albert Weisbord considers him an individualist anarchist without reservation.[104] Some writers see a conflict between Godwin's advocacy of "private judgement" and utilitarianism as he says that ethics requires that individuals give their surplus property to each other resulting in an egalitarian society, but at the same time he insists that all things be left to individual choice.[14] As noted by Kropotkin, many of Godwin's views changed over time.

William Godwin's influenced "the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren, considered to be the first individualist anarchist. After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his ideological loyalties from socialism to anarchism. According to anarchist Peter Sabatini, this "was no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism".[105]

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first philosopher to label himself an "anarchist".[106] Some consider Proudhon to be an individualist anarchist[107][108][109] while others regard him to be a social anarchist.[110][111] Some commentators do not identify Proudhon as an individualist anarchist due to his preference for association in large industries, rather than individual control.[112] Nevertheless, he was influential among some of the American individualists – in the 1840s and 1850s, Charles Anderson Dana[113] and William Batchelder Greene introduced Proudhon's works to the United States. Greene adapted Proudhon's mutualism to American conditions and introduced it to Benjamin Tucker.[114]

Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist, banking and land interests and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. Proudhon favoured a right of individuals to retain the product of their labour as their own property, but he believed that any property beyond that which an individual produced and could possess was illegitimate. Thus he saw private property as both essential to liberty and a road to tyranny, the former when it resulted from labour and was required for labour and the latter when it resulted in exploitation (profit, interest, rent and tax). He generally called the former "possession" and the latter "property". For large-scale industry, he supported workers associations to replace wage labour and opposed the ownership of land.

Proudhon maintained that those who labour should retain the entirety of what they produce and that monopolies on credit and land are the forces that prohibit such. He advocated an economic system that included private property as possession and exchange market, but without profit, which he called mutualism. It is Proudhon's philosophy that was explicitly rejected by Joseph Déjacque in the inception of anarcho-communism, with the latter asserting directly to Proudhon in a letter that "it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature". An individualist rather than anarcho-communist,[107][108][109] Proudhon said that "communism [...] is the very denial of society in its foundation"[115] and famously declared that "property is theft" in reference to his rejection of ownership rights to land being granted to a person who is not using that land.

After Déjacque and others split from Proudhon due to the latter's support of individual property and an exchange economy, the relationship between the individualists (who continued in relative alignment with the philosophy of Proudhon) and the anarcho-communists was characterised by various degrees of antagonism and harmony. For example, individualists like Tucker on the one hand translated and reprinted the works of collectivists like Mikhail Bakunin while on the other hand rejected the economic aspects of collectivism and communism as incompatible with anarchist ideals.

Mutualism

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought which can be traced to the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market.[116] Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank which would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate only high enough to cover the costs of administration.[117] Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value which holds that when labour or its product is sold, in exchange it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[118] Some mutualists believe that if the state did not intervene, individuals would receive no more income than that in proportion to the amount of labor they exert as a result of increased competition in the marketplace.[119][120] Mutualists oppose the idea of individuals receiving an income through loans, investments and rent as they believe these individuals are not labouring. Some of them argue that if state intervention ceased, these types of incomes would disappear due to increased competition in capital.[121][122] Although Proudhon opposed this type of income, he expressed that he "never meant to [...] forbid or suppress, by sovereign decree, ground rent and interest on capital. I believe that all these forms of human activity should remain free and optional for all".[123]

Mutualists argue for conditional titles to land, whose private ownership is legitimate only so long as it remains in use or occupation (which Proudhon called "possession").[124] Proudhon's mutualism supports labor-owned cooperative firms and associations[125] for "we need not hesitate, for we have no choice [...] it is necessary to form an ASSOCIATION among workers [...] because without that, they would remain related as subordinates and superiors, and there would ensue two [...] castes of masters and wage-workers, which is repugnant to a free and democratic society" and so "it becomes necessary for the workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism".[126] As for capital goods (man-made and non-land, means of production), mutualist opinion differs on whether these should be common property and commonly managed public assets or private property in the form of worker cooperatives, for as long as they ensure the worker's right to the full product of their labor, mutualists support markets and property in the product of labor, differentiating between capitalist private property (productive property) and personal property (private property).[127][128]

Following Proudhon, mutualists are libertarian socialists who consider themselves to part of the market socialist tradition and the socialist movement. However, some contemporary mutualists outside the classical anarchist tradition abandoned the labor theory of value and prefer to avoid the term socialist due to its association with state socialism throughout the 20th century. Nonetheless, those contemporary mutualists "still retain some cultural attitudes, for the most part, that set them off from the libertarian right. Most of them view mutualism as an alternative to capitalism, and believe that capitalism as it exists is a statist system with exploitative features".[129] Mutualists have distinguished themselves from state socialism and do not advocate state ownership over the means of production. Benjamin Tucker said of Proudhon that "though opposed to socializing the ownership of capital, Proudhon aimed nevertheless to socialize its effects by making its use beneficial to all instead of a means of impoverishing the many to enrich the few [...] by subjecting capital to the natural law of competition, thus bringing the price of its own use down to cost".[19]

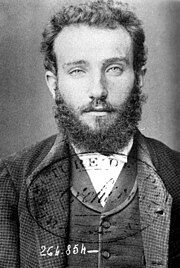

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt, better known as Max Stirner (the pen name he adopted from a schoolyard nickname he had acquired as a child because of his high brow, in German Stirn), was a German philosopher who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism. Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own, also known as The Ego and His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum in German which translates literally as The Only One [individual] and his Property or The Unique Individual and His Property).[130] This work was first published in 1844 in Leipzig and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.

Egoism

Max Stirner's philosophy, sometimes called egoism, is a form of individualist anarchism.[131] Stirner was a Hegelian philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically oriented surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best-known exponents of individualist anarchism".[15] In 1844, Stirner's work The Ego and Its Own was published and is considered to be "a founding text in the tradition of individualist anarchism".[15] Stirner does not recommend that the individual try to eliminate the state, but simply that they disregard the state when it conflicts with one's autonomous choices and go along with it when doing so is conducive to one's interests.[132] Stirner says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a good cause, a doctrine, a system, a lofty calling", arguing that the egoist has no political calling, but rather "lives themselves out" without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby".[133] Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual is that individual's power to obtain what he desires.[134] Stirner proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions, including the notion of state, property as a right, natural rights in general and the very notion of "society" as a legal and ideal abstractness, were mere spooks in the mind. Stirner wants to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members".[135] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw Union of egoists, non-systematic associations which he proposed in as a form of organization in place of the state.[136] A Union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will.[93][137] Even murder is permissible "if it is right for me",[138] although it is claimed by egoist anarchists that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous unions between individuals.[139]

For Stirner, property simply comes about through might, arguing that "[w]hoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property". He further says that "[w]hat I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing" and that "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!"[140] His concept of "egoistic property" not only a lack of moral restraint on how one obtains and uses things, but includes other people as well.[141] His embrace of egotism is in stark contrast to Godwin's altruism. Although Stirner was opposed to communism, for the same reasons he opposed capitalism, humanism, liberalism, property rights and nationalism, seeing them as forms of authority over the individual and as spooks in the mind, he has influenced many anarcho-communists and post-left anarchists. The writers of An Anarchist FAQ report that "many in the anarchist movement in Glasgow, Scotland, took Stirner's 'Union of egoists' literally as the basis for their anarcho-syndicalist organising in the 1940s and beyond". Similarly, the noted anarchist historian Max Nettlau states that "[o]n reading Stirner, I maintain that he cannot be interpreted except in a socialist sense".[142] Stirner does not personally oppose the struggles carried out by certain ideologies such as socialism, humanism or the advocacy of human rights. Rather, he opposes their legal and ideal abstractness, a fact that makes him different from the liberal individualists, including the anarcho-capitalists and right-libertarians, but also from the Übermensch theories of fascism as he places the individual at the center and not the sacred collective. About socialism, Stirner wrote in a letter to Moses Hess that "I am not at all against socialism, but against consecrated socialism; my selfishness is not opposed to love [...] nor is it an enemy of sacrifice, nor of self-denial [...] and least of all of socialism [...] – in short, it is not an enemy of true interests; it rebels not against love, but against sacred love, not against thought, but against sacred thought, not against socialists, but against sacred socialism".[143]

This position on property is quite different from the Native American, natural law, form of individualist anarchism which defends the inviolability of the private property that has been earned through labor.[144] However, Benjamin Tucker rejected the natural rights philosophy and adopted Stirner's egoism in 1886, with several others joining with him. This split the American individualists into fierce debate, "with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself".[145] Other egoists include James L. Walker, Sidney Parker, Dora Marsden and John Beverly Robinson. In Russia, individualist anarchism inspired by Stirner combined with an appreciation for Friedrich Nietzsche attracted a small following of bohemian artists and intellectuals such as Lev Chernyi as well as a few lone wolves who found self-expression in crime and violence.[146] They rejected organizing, believing that only unorganized individuals were safe from coercion and domination, believing this kept them true to the ideals of anarchism.[147] This type of individualist anarchism inspired anarcha-feminist Emma Goldman.[146]

Forms of libertarian communism such as Situationism are influenced by Stirner.[148] Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman was influenced by both Stirner and Peter Kropotkin and blended their philosophies together in her own as shown in books of hers such as Anarchism And Other Essays.[149]

Early individualist anarchism in the United States

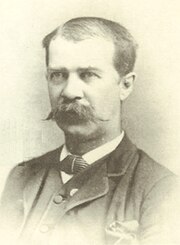

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[150] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published,[151] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[151] Warren was a follower of Robert Owen and joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana. Warren termed the phrase "Cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item.[152] Therefore, "[h]e proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce".[150] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included Utopia and Modern Times. Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society (published in 1852) was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories.[153] Catalan historian Xavier Diez report that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand and the intentional communities started by them.[154]

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau was an important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the United States and Europe. Thoreau was an American author, poet, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian, philosopher and leading transcendentalist. He is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings; and his essay, Civil Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state. His thought is an early influence on green anarchism, but with an emphasis on the individual experience of the natural world influencing later naturist currents,[16] simple living as a rejection of a materialist lifestyle[16] and self-sufficiency were Thoreau's goals and the whole project was inspired by transcendentalist philosophy. Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and anarcho-primitivism represented today in John Zerzan. For George Woodcock, this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid 19th century.[87]

The essay "Civil Disobedience" (Resistance to Civil Government) was first published in 1849. It argues that people should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences and that people have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. Thoreau was motivated in part by his disgust with slavery and the Mexican–American War. The essay later influenced Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Buber and Leo Tolstoy through its advocacy of nonviolent resistance.[155] It is also the main precedent for anarcho-pacifism.[155] The American version of individualist anarchism has a strong emphasis on the non-aggression principle and individual sovereignty.[156] Some individualist anarchists such as Thoreau[157][158] do not speak of economics, but simply of the right of "disunion" from the state and foresee the gradual elimination of the state through social evolution.

Developments and expansion

Anarcha-feminism, free love, freethought and LGBT issues

An important current within individualist anarchism is free love.[85] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws, such as those governing marriage and use of birth control, discriminated against women.[85] The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois Waisbrooker[159] but also there existed Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood's The Word (1872–1890, 1892–1893).[85] M. E. Lazarus was also an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.[85]

In Europe, the main propagandist of free love within individualist anarchism was Émile Armand.[160] He proposed the concept of la camaraderie amoureuse to speak of free love as the possibility of voluntary sexual encounter between consenting adults. He was also a consistent proponent of polyamory.[160] In France, there was also feminist activity inside individualist anarchism as promoted by individualist feminists Marie Küge, Anna Mahé, Rirette Maîtrejean and Sophia Zaïkovska.[161]

The Brazilian individualist anarchist Maria Lacerda de Moura lectured on topics such as education, women's rights, free love and antimilitarism. Her writings and essays garnered her attention not only in Brazil, but also in Argentina and Uruguay.[162] She also wrote for the Spanish individualist anarchist magazine Al Margen alongside Miguel Giménez Igualada.[163] In Germany, the Stirnerists Adolf Brand and John Henry Mackay were pioneering campaigners for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.

Freethought as a philosophical position and as activism was important in both North American and European individualist anarchism, but in the United States freethought was basically an anti-Christian, anti-clerical movement whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of Freethought and for a time The Truth Seeker. E.C. Walker was co-editor of Lucifer, the Light-Bearer.[164] Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty. The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself.[164]

In Europe, a similar development occurred in French and Spanish individualist anarchist circles: "Anticlericalism, just as in the rest of the libertarian movement, is another of the frequent elements which will gain relevance related to the measure in which the (French) Republic begins to have conflicts with the church [...] Anti-clerical discourse, frequently called for by the french individualist André Lorulot, will have its impacts in Estudios (a Spanish individualist anarchist publication). There will be an attack on institutionalized religion for the responsibility that it had in the past on negative developments, for its irrationality which makes it a counterpoint of philosophical and scientific progress. There will be a criticism of proselitism and ideological manipulation which happens on both believers and agnostics".[165] This tendencies will continue in French individualist anarchism in the work and activism of Charles-Auguste Bontemps and others. In the Spanish individualist anarchist magazine Ética and Iniciales, "there is a strong interest in publishing scientific news, usually linked to a certain atheist and anti-theist obsession, philosophy which will also work for pointing out the incompatibility between science and religion, faith and reason. In this way there will be a lot of talk on Darwin's theories or on the negation of the existence of the soul".[166]

Anarcho-naturism

Another important current, especially within French and Spanish[87][167] individualist anarchist groups was naturism.[168] Naturism promoted an ecological worldview, small ecovillages and most prominently nudism as a way to avoid the artificiality of the industrial mass society of modernity. Naturist individualist anarchists saw the individual in his biological, physical and psychological aspects and avoided and tried to eliminate social determinations.[169] An early influence in this vein was Henry David Thoreau and his famous book Walden.[170] Important promoters of this were Henri Zisly and Émile Gravelle who collaborated in La Nouvelle Humanité followed by Le Naturien, Le Sauvage, L'Ordre Naturel and La Vie Naturelle.[171][172]

This relationship between anarchism and naturism was quite important at the end of the 1920s in Spain,[173] when "[t]he linking role played by the 'Sol y Vida' group was very important. The goal of this group was to take trips and enjoy the open air. The Naturist athenaeum, 'Ecléctico', in Barcelona, was the base from which the activities of the group were launched. First Etica and then Iniciales, which began in 1929, were the publications of the group, which lasted until the Spanish Civil War. We must be aware that the naturist ideas expressed in them matched the desires that the libertarian youth had of breaking up with the conventions of the bourgeoisie of the time. That is what a young worker explained in a letter to 'Iniciales' He writes it under the odd pseudonym of 'silvestre del campo', (wild man in the country). "I find great pleasure in being naked in the woods, bathed in light and air, two natural elements we cannot do without. By shunning the humble garment of an exploited person, (garments which, in my opinion, are the result of all the laws devised to make our lives bitter), we feel there no others left but just the natural laws. Clothes mean slavery for some and tyranny for others. Only the naked man who rebels against all norms, stands for anarchism, devoid of the prejudices of outfit imposed by our money-oriented society".[173] The relation between anarchism and naturism "gives way to the Naturist Federation, in July 1928, and to the lV Spanish Naturist Congress, in September 1929, both supported by the Libertarian Movement. However, in the short term, the Naturist and Libertarian movements grew apart in their conceptions of everyday life. The Naturist movement felt closer to the Libertarian individualism of some French theoreticians such as Henri Ner (real name of Han Ryner) than to the revolutionary goals proposed by some Anarchist organisations such as the FAI, (Federación Anarquista Ibérica)".[173]

Individualist anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche

The thought of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche has been influential in individualist anarchism, specifically in thinkers such as France's Émile Armand,[174] the Italian Renzo Novatore[175] and the Colombian Biofilo Panclasta. Robert C. Holub, author of Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist posits that "translations of Nietzsche's writings in the United States very likely appeared first in Liberty, the anarchist journal edited by Benjamin Tucker".[176]

Individualist anarchism in the United States

Mutualism and utopianism

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent [...] that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews [...] William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[177] William Batchelder Greene is best known for the works Mutual Banking (1850) which proposed an interest-free banking system and Transcendentalism, a critique of the New England philosophical school. He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order".[177] His "associationism [...] is checked by individualism. [...] 'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage – the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property[177] and feminist and spiritualist tendencies".[178] Within some individualist anarchist circles, mutualism came to mean non-communist anarchism.[179]

Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey reports that "Steven Pearl Andrews [...] was not a fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America & adopted a lot of fourierist principles & practices, [...] a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized Abolitionism, Free Love, spiritual universalism, [Josiah] Warren, & [Charles] Fourier into a grand utopian scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy. [...] He was instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th St. in New York, & 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts & the North American Phalanx in New Jersey) – in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious (for 'Free Love') & finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (& Victoria Woodhull) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International, expelled by Marx for its anarchist, feminist, & spiritualist tendencies".[178]

Boston anarchists

Another form of individualist anarchism was found in the United States as advocated by the so-called Boston anarchists.[146] By default, American individualists had no difficulty accepting the concepts that "one man employ another" or that "he direct him", in his labor but rather demanded that "all natural opportunities requisite to the production of wealth be accessible to all on equal terms and that monopolies arising from special privileges created by law be abolished".[180]

They believed state monopoly capitalism (defined as a state-sponsored monopoly)[181] prevented labor from being fully rewarded. Voltairine de Cleyre summed up the philosophy by saying that the anarchist individualists "are firm in the idea that the system of employer and employed, buying and selling, banking, and all the other essential institutions of Commercialism, centred upon private property, are in themselves good, and are rendered vicious merely by the interference of the State".[182]

Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including intellectual property rights and possession versus property in land.[183][184][185] A major schism occurred later in the 19th century when Tucker and some others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights as espoused by Lysander Spooner and converted to an "egoism" modeled upon Max Stirner's philosophy.[184] Lysander Spooner besides his individualist anarchist activism was also an important anti-slavery activist and became a member of the First International.[186]

Some Boston anarchists, including Benjamin Tucker, identified themselves as socialists, which in the 19th century was often used in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. "the labor problem").[187] The Boston anarchists such as Tucker and his followers continue to be considered socialists due to their opposition to usury.[188] They do so because as the modern economist Jim Stanford points out there are many different kinds of competitive markets such as market socialism and capitalism is only one type of a market economy.[189] By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed.[190]

Individualist anarchism and the labor movement

George Woodcock reports that the American individualist anarchists Lysander Spooner and William B. Greene had been members of the socialist First International.[191]

Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's Liberty were also important labor organizers of the time. Joseph Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist and poet. In 1883, Labadie embraced a non-violent version of individualist anarchism. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws [...] without robbing [their] fellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes". However, he supported community cooperation as he supported community control of water utilities, streets and railroads.[192] Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for the clemency of the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators. In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers. A colleague of Labadie's at Liberty, Dyer Lum was another important individualist anarchist labor activist and poet of the era.[193] A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s,[194] he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.[195]

Lum was a prolific writer who wrote a number of key anarchist texts and contributed to publications including Mother Earth, Twentieth Century, The Alarm (the journal of the International Working People's Association) and The Open Court among others. Lum's political philosophy was a fusion of individualist anarchist economics – "a radicalized form of laissez-faire economics" inspired by the Boston anarchists – with radical labor organization similar to that of the Chicago anarchists of the time.[196] Herbert Spencer and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon influenced Lum strongly in his individualist tendency.[196] He developed a "mutualist" theory of unions and as such was active within the Knights of Labor and later promoted anti-political strategies in the American Federation of Labor.[196] Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and radicalize workers.[196] Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery.[197] Kevin Carson has praised Lum's fusion of individualist laissez-faire economics with radical labor activism as "creative" and described him as "more significant than any in the Boston group".[196]

Egoist anarchism

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract". He also said after converting to Egoist individualism that "[i]n times past [...] it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off [...] Man's only right to land is his might over it".[198] In adopting Stirnerite egoism in 1886, Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism in the United States. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly.[199]

Several periodicals were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism. They included I published by Clarence Lee Swartz, edited by William Walstein Gordak and J. William Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); and The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand; and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle "A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology".[200]

American anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker, John Beverley Robinson, Steven T. Byington, Hutchins Hapgood, James L. Walker, Victor Yarros and Edward H. Fulton.[201] Robinson wrote an essay called "Egoism" in which he states that "[m]odern egoism, as propounded by Stirner and Nietzsche, and expounded by Ibsen, Shaw and others, is all these; but it is more. It is the realization by the individual that they are an individual; that, as far as they are concerned, they are the only individual".[202] Walker published the work The Philosophy of Egoism in which he argued that egoism "implies a rethinking of the self-other relationship, nothing less than 'a complete revolution in the relations of mankind' that avoids both the 'archist' principle that legitimates domination and the 'moralist' notion that elevates self-renunciation to a virtue. Walker describes himself as an 'egoistic anarchist' who believed in both contract and cooperation as practical principles to guide everyday interactions".[203] For Walker, "what really defines egoism is not mere self-interest, pleasure, or greed; it is the sovereignty of the individual, the full expression of the subjectivity of the individual ego".[204]

Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States[205] by Italian born individualists such as Giuseppe Ciancabilla and others who advocated for violent propaganda by the deed there. Anarchist historian George Woodcock reports the incident in which the important Italian social anarchist Errico Malatesta became involved "in a dispute with the individualist anarchists of Paterson, who insisted that anarchism implied no organization at all, and that every man must act solely on his impulses. At last, in one noisy debate, the individual impulse of a certain Ciancabilla directed him to shoot Malatesta, who was badly wounded but obstinately refused to name his assailant".[206]

Enrico Arrigoni (pseudonym Frank Brand) was an Italian American individualist anarchist Lathe operator, house painter, bricklayer, dramatist and political activist influenced by the work of Max Stirner.[207][208] He took the pseudonym Brand from a fictional character in one of Henrik Ibsen's plays.[208] In the 1910s, he started becoming involved in anarchist and anti-war activism around Milan.[208] From the 1910s until the 1920s, he participated in anarchist activities and popular uprisings in various countries including Switzerland, Germany, Hungary, Argentina and Cuba.[208] He lived from the 1920s onwards in New York City, where he edited the individualist anarchist eclectic journal Eresia in 1928. He also wrote for other American anarchist publications such as L' Adunata dei refrattari, Cultura Obrera, Controcorrente and Intesa Libertaria.[208] During the Spanish Civil War, he went to fight with the anarchists, but he was imprisoned and was helped on his release by Emma Goldman.[207][208] Afterwards, Arrigoni became a longtime member of the Libertarian Book Club in New York City.[208] His written works include The Totalitarian Nightmare (1975), The Lunacy of the Superman (1977), Adventures in the Country of the Monoliths (1981) and Freedom: My Dream (1986).[208]

Post-left anarchy and insurrectionary anarchism

Murray Bookchin has identified post-left anarchy as a form of individualist anarchism in Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm where he identifies "a shift among Euro-American anarchists away from social anarchism and toward individualist or lifestyle anarchism. Indeed, lifestyle anarchism today is finding its principal expression in spray-can graffiti, post-modernist nihilism, antirationalism, neoprimitivism, anti-technologism, neo-Situationist 'cultural terrorism', mysticism, and a 'practice' of staging Foucauldian 'personal insurrections'".[209] Post-left anarchist Bob Black in his long critique of Bookchin's philosophy called Anarchy After Leftism said about post-left anarchy that "[i]t is, unlike Bookchinism, "individualistic" in the sense that if the freedom and happiness of the individual – i.e., each and every really existing person, every Tom, Dick and Murray – is not the measure of the good society, what is?"[210]

A strong relationship does exist between post-left anarchism and the work of individualist anarchist Max Stirner. Jason McQuinn says that "when I (and other anti-ideological anarchists) criticize ideology, it is always from a specifically critical, anarchist perspective rooted in both the skeptical, individualist-anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner.[211] Bob Black and Feral Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher also strongly adhere to stirnerist egoist anarchism. Bob Black has humorously suggested the idea of "marxist stirnerism".[212]

Hakim Bey has said that "[f]rom Stirner's 'Union of Self-Owning Ones' we proceed to Nietzsche's circle of 'Free Spirits' and thence to Charles Fourier's 'Passional Series', doubling and redoubling ourselves even as the Other multiplies itself in the eros of the group".[213] Bey also wrote that "[t]he Mackay Society, of which Mark & I are active members, is devoted to the anarchism of Max Stirner, Benj. Tucker & John Henry Mackay. [...] The Mackay Society, incidentally, represents a little-known current of individualist thought which never cut its ties with revolutionary labor. Dyer Lum, Ezra & Angela Haywood represent this school of thought; Jo Labadie, who wrote for Tucker's Liberty, made himself a link between the American 'plumb-line' anarchists, the 'philosophical' individualists, & the syndicalist or communist branch of the movement; his influence reached the Mackay Society through his son, Laurance. Like the Italian Stirnerites (who influenced us through our late friend Enrico Arrigoni) we support all anti-authoritarian currents, despite their apparent contradictions".[214]

As far as posterior individualist anarchists, Jason McQuinn for some time used the pseudonym Lev Chernyi in honor of the Russian individualist anarchist of the same name while Feral Faun has quoted Italian individualist anarchist Renzo Novatore[215] and has translated both Novatore[216] and the young Italian individualist anarchist Bruno Filippi[217]

Egoism has had a strong influence on insurrectionary anarchism as can be seen in the work of Wolfi Landstreicher. Feral Faun wrote in 1995:

In the game of insurgence – a lived guerilla war game – it is strategically necessary to use identities and roles. Unfortunately, the context of social relationships gives these roles and identities the power to define the individual who attempts to use them. So I, Feral Faun, became [...] an anarchist, [...] a writer, [...] a Stirner-influenced, post-situationist, anti-civilization theorist, [...] if not in my own eyes, at least in the eyes of most people who've read my writings.[218]

Individualist anarchism in Europe

European individualist anarchism proceeded from the roots laid by William Godwin,[93] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Max Stirner. Proudhon was an early pioneer of anarchism as well as of the important individualist anarchist current of mutualism.[107][108] Stirner became a central figure of individualist anarchism through the publication of his seminal work The Ego and Its Own which is considered to be "a founding text in the tradition of individualist anarchism".[15] Another early figure was Anselme Bellegarrigue.[219] Individualist anarchism expanded and diversified through Europe, incorporating influences from North American individualist anarchism.

European individualist anarchists include Albert Libertad, Bellegarrigue, Oscar Wilde, Émile Armand, Lev Chernyi, John Henry Mackay, Han Ryner, Adolf Brand, Miguel Giménez Igualada, Renzo Novatore and currently Michel Onfray.[220] Important currents within it include free love,[221] anarcho-naturism[221] and illegalism.[222]

France

From the legacy of Proudhon and Stirner there emerged a strong tradition of French individualist anarchism. An early important individualist anarchist was Anselme Bellegarrigue. He participated in the French Revolution of 1848, was author and editor of Anarchie, Journal de l'Ordre and Au fait ! Au fait ! Interprétation de l'idée démocratique and wrote the important early Anarchist Manifesto in 1850. Catalan historian of individualist anarchism Xavier Diez reports that during his travels in the United States "he at least contacted (Henry David) Thoreau and, probably (Josiah) Warren".[223] Autonomie Individuelle was an individualist anarchist publication that ran from 1887 to 1888. It was edited by Jean-Baptiste Louiche, Charles Schæffer and Georges Deherme.[224]

Later, this tradition continued with such intellectuals as Albert Libertad, André Lorulot, Émile Armand, Victor Serge, Zo d'Axa and Rirette Maîtrejean, who in 1905 developed theory in the main individualist anarchist journal in France, L'Anarchie.[225] Outside this journal, Han Ryner wrote Petit Manuel individualiste (1903). In 1891, Zo d'Axa created the journal L'En-Dehors.

Anarcho-naturism was promoted by Henri Zisly, Émile Gravelle[171] and Georges Butaud. Butaud was an individualist "partisan of the milieux libres, publisher of 'Flambeau' ('an enemy of authority') in 1901 in Vienna" and most of his energies were devoted to creating anarchist colonies (communautés expérimentales) in which he participated in several.[226]

In this sense, "the theoretical positions and the vital experiences of [F]rench individualism are deeply iconoclastic and scandalous, even within libertarian circles. The call of nudist naturism, the strong defence of birth control methods, the idea of "unions of egoists" with the sole justification of sexual practices, that will try to put in practice, not without difficulties, will establish a way of thought and action, and will result in sympathy within some, and a strong rejection within others".[86]

French individualist anarchists grouped behind Émile Armand, published L'Unique after World War II. L'Unique went from 1945 to 1956 with a total of 110 numbers.[227][228] Gérard de Lacaze-Duthiers was a French writer, art critic, pacifist and anarchist. Lacaze-Duthiers, an art critic for the Symbolist review journal La Plume, was influenced by Oscar Wilde, Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Stirner. His (1906) L'Ideal Humain de l'Art helped found the "artistocracy movement" – a movement advocating life in the service of art.[229] His ideal was an anti-elitist aestheticism: "All men should be artists".[230] Together with André Colomer and Manuel Devaldes, in 1913 he founded L'Action d'Art, an anarchist literary journal.[231] After World War II, he contributed to the journal L'Unique.[232] Within the synthesist anarchist organization, the Fédération Anarchiste, there existed an individualist anarchist tendency alongside anarcho-communist and anarchosyndicalist currents.[233] Individualist anarchists participating inside the Fédération Anarchiste included Charles-Auguste Bontemps, Georges Vincey and André Arru.[234] The new base principles of the francophone Anarchist Federation were written by the individualist anarchist Charles-Auguste Bontemps and the anarcho-communist Maurice Joyeux which established an organization with a plurality of tendencies and autonomy of federated groups organized around synthesist principles.[235] Charles-Auguste Bontemps was a prolific author mainly in the anarchist, freethinking, pacifist and naturist press of the time.[235] His view on anarchism was based around his concept of "Social Individualism" on which he wrote extensively.[235] He defended an anarchist perspective which consisted on "a collectivism of things and an individualism of persons".[236]

In 2002, Libertad organized a new version of the L'EnDehors, collaborating with Green Anarchy and including several contributors, such as Lawrence Jarach, Patrick Mignard, Thierry Lodé, Ron Sakolsky and Thomas Slut. Numerous articles about capitalism, human rights, free love and social fights were published. The EnDehors continues now as a website, EnDehors.org.

The prolific contemporary French philosopher Michel Onfray has been writing from an individualist anarchist[220][237] perspective influenced by Nietzsche, French post-structuralists thinkers such as Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze; and Greek classical schools of philosophy such as the Cynics and Cyrenaics. Among the books which best expose Onfray's individualist anarchist perspective include La sculpture de soi : la morale esthétique (The Sculpture of Oneself: Aesthetic Morality), La philosophie féroce : exercices anarchistes, La puissance d'exister and Physiologie de Georges Palante, portrait d'un nietzchéen de gauche which focuses on French individualist philosopher Georges Palante.

Illegalism

Illegalism[80] is an anarchist philosophy that developed primarily in France, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland during the early 1900s as an outgrowth of Stirner's individualist anarchism.[222] Illegalists usually did not seek moral basis for their actions, recognizing only the reality of "might" rather than "right"; and for the most part, illegal acts were done simply to satisfy personal desires, not for some greater ideal,[81] although some committed crimes as a form of propaganda of the deed.[80] The illegalists embraced direct action and propaganda of the deed.[238]

Influenced by theorist Max Stirner's egoism as well as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (his view that "property is theft!"), Clément Duval and Marius Jacob proposed the theory of la reprise individuelle (individual reclamation) which justified robbery on the rich and personal direct action against exploiters and the system.[81]

Illegalism first rose to prominence among a generation of Europeans inspired by the unrest of the 1890s, during which Ravachol, Émile Henry, Auguste Vaillant and Sante Geronimo Caserio committed daring crimes in the name of anarchism[239] in what is known as propaganda of the deed. France's Bonnot Gang was the most famous group to embrace illegalism.

Germany

In Germany, the Scottish-German John Henry Mackay became the most important propagandist for individualist anarchist ideas. He fused Stirnerist egoism with the positions of Benjamin Tucker and actually translated Tucker into German. Two semi-fictional writings of his own, Die Anarchisten and Der Freiheitsucher, contributed to individualist theory through an updating of egoist themes within a consideration of the anarchist movement. English translations of these works arrived in the United Kingdom and in individualist American circles led by Tucker.[240] Mackay is also known as an important European early activist for gay rights. Using the pseudonym Sagitta, Mackay wrote a series of works for pederastic emancipation, titled Die Buecher der namenlosen Liebe (Books of the Nameless Love). This series was conceived in 1905 and completed in 1913 and included the Fenny Skaller, a story of a pederast.[241] Under the same pseudonym, he also published fiction, such as Holland (1924) and a pederastic novel of the Berlin boy-bars, Der Puppenjunge (The Hustler) (1926).

Adolf Brand was a German writer, Stirnerist anarchist and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality. In 1896, Brand published a German homosexual periodical, Der Eigene. This was the first ongoing homosexual publication in the world.[242] The name was taken from writings of egoist philosopher Max Stirner (who had greatly influenced the young Brand) and refers to Stirner's concept of "self-ownership" of the individual. Der Eigene concentrated on cultural and scholarly material and may have had an average of around 1,500 subscribers per issue during its lifetime, although the exact numbers are uncertain. Contributors included Erich Mühsam, Kurt Hiller, John Henry Mackay (under the pseudonym Sagitta) and artists Wilhelm von Gloeden, Fidus and Sascha Schneider. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself. Benjamin Tucker followed this journal from the United States.[243]

Der Einzige was a German individualist anarchist magazine. It appeared in 1919 as a weekly, then sporadically until 1925 and was edited by cousins Anselm Ruest (pseudonym for Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (pseudonym for Salomo Friedlaender). Its title was adopted from the book Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (The Ego and Its Own) by Max Stirner. Another influence was the thought of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.[244] The publication was connected to the local expressionist artistic current and the transition from it towards Dada.[245]

Italy

In Italy, individualist anarchism had a strong tendency towards illegalism and violent propaganda by the deed similar to French individualist anarchism, but perhaps more extreme[246][247] and which emphazised criticism of organization be it anarchist or of other type.[248] In this respect, we can consider notorious magnicides carried out or attempted by individualists Giovanni Passannante, Sante Caserio, Michele Angiolillo, Luigi Lucheni and Gaetano Bresci who murdered King Umberto I. Caserio lived in France and coexisted within French illegalism and later assassinated French President Sadi Carnot. The theoretical seeds of current insurrectionary anarchism were already laid out at the end of 19th century Italy in a combination of individualist anarchism criticism of permanent groups and organization with a socialist class struggle worldview.[249] During the rise of fascism, this thought also motivated Gino Lucetti, Michele Schirru and Angelo Sbardellotto in attempting the assassination of Benito Mussolini.

During the early 20th century, the intellectual work of individualist anarchist Renzo Novatore came to importance and he was influenced by Max Stirner, Friedrich Nietzsche, Georges Palante, Oscar Wilde, Henrik Ibsen, Arthur Schopenhauer and Charles Baudelaire. He collaborated in numerous anarchist journals and participated in futurism avant-garde currents. In his thought, he adhered to Stirnerist disrespect for private property, only recognizing property of one's own spirit.[250] Novatore collaborated in the individualist anarchist journal Iconoclasta! alongside the young Stirnerist illegalist Bruno Filippi.[217]

The individualist philosopher and poet Renzo Novatore belonged to the leftist section of the avant-garde movement of futurism[251] alongside other individualist anarcho-futurists such as Dante Carnesecchi, Leda Rafanelli, Auro d'Arcola and Giovanni Governato. There was also Pietro Bruzzi who published the journal L'Individualista in the 1920s alongside Ugo Fedeli and Francesco Ghezzi, but who fell to fascist forces later.[252][253] Bruzzi also collaborated with the Italian American individualist anarchist publication Eresia of New York City[253] edited by Enrico Arrigoni.

During the Founding Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation in 1945, there was a group of individualist anarchists led by Cesare Zaccaria[254] who was an important anarchist of the time.[255] Later during the IX Congress of the Italian Anarchist Federation in Carrara in 1965, a group decided to split off from this organization and created the Gruppi di Iniziativa Anarchica. In the 1970s, it was mostly composed of "veteran individualist anarchists with an of pacifism orientation, naturism".[256]

In the famous Italian insurrectionary anarchist essay written by an anonymous writer, "At Daggers Drawn with the Existent, its Defenders and its False Critics", there reads how "[t]he workers who, during a wildcat strike, carried a banner saying, 'We are not asking for anything' understood that the defeat is in the claim itself ('the claim against the enemy is eternal'). There is no alternative but to take everything. As Stirner said: 'No matter how much you give them, they will always ask for more, because what they want is no less than the end of every concession'".[257] The contemporary imprisoned Italian insurrectionary anarchist philosopher Michele Fabiani writes from an explicit individualist anarchist perspective in such essays as Critica individualista anarchica alla modernità ("Individualist Anarchist Critique of Modernity").[258] Horst Fantazzini (1939–2001)[259] was an Italian-German individualist anarchist[260] who pursued an illegalist lifestyle and practice until his death in 2001. He gained media notoriety mainly due to his many bank robberies through Italy and other countries.[259] In 1999, the film Ormai è fatta! appeared based on his life.[261]

Russia

Individualist anarchism was one of the three categories of anarchism in Russia, along with the more prominent anarcho-communism and anarcho-syndicalism.[262] The ranks of the Russian individualist anarchists were predominantly drawn from the intelligentsia and the working class.[262] For anarchist historian Paul Avrich, "[t]he two leading exponents of individualist anarchism, both based in Moscow, were Aleksei Alekseevich Borovoi and Lev Chernyi (born Pavel Dmitrievich Turchaninov). From Nietzsche, they inherited the desire for a complete overturn of all values accepted by bourgeois society political, moral, and cultural. Furthermore, strongly influenced by Max Stirner and Benjamin Tucker, the German and American theorists of individualist anarchism, they demanded the total liberation of the human personality from the fetters of organized society".[262]

Some Russian individualists anarchists "found the ultimate expression of their social alienation in violence and crime, others attached themselves to avant-garde literary and artistic circles, but the majority remained "philosophical" anarchists who conducted animated parlor discussions and elaborated their individualist theories in ponderous journals and books".[262]

Lev Chernyi was an important individualist anarchist involved in resistance against the rise to power of the Bolshevik Party as he adhered mainly to Stirner and the ideas of Tucker. In 1907, he published a book entitled Associational Anarchism in which he advocated the "free association of independent individuals".[263] On his return from Siberia in 1917, he enjoyed great popularity among Moscow workers as a lecturer. Chernyi was also Secretary of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups, which was formed in March 1917.[263] He was an advocate "for the seizure of private homes",[263] which was an activity seen by the anarchists after the October Revolution as direct expropriation on the bourgoise. He died after being accused of participation in an episode in which this group bombed the headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party. Although most likely not being really involved in the bombing, he might have died of torture.[263]

Chernyi advocated a Nietzschean overthrow of the values of bourgeois Russian society, and rejected the voluntary communes of anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin as a threat to the freedom of the individual.[264][265][266] Scholars including Avrich and Allan Antliff have interpreted this vision of society to have been greatly influenced by the individualist anarchists Max Stirner and Benjamin Tucker.[267] Subsequent to the book's publication, Chernyi was imprisoned in Siberia under the Russian Czarist regime for his revolutionary activities.[268]