Madonna and contemporary arts

The contributions and influence of American artist Madonna (born 1958) in the landscape of contemporary arts have been documented by a variety of sources such as art publications, mainstream media, scholars or art critics. As her footprints in the arts are lesser-known compared to her other roles, this led a contributor from W to conclude that both her impact and influence in the art world "has been made almost entirely behind the scenes". She is noted for taking inspiration from various painters in her career. Once called a "continuous multi-media art project", a panel of art critics explained that she condenses fashion, dance, photography, sculpture, music, video and painting in her own artwork.

Madonna's interest in the arts began in her early life. When she moved to New York City to pursue a career in the modern dance, she befriended and dated various painters, graffiti, and visual artists, including Andy Warhol, Martin Burgoyne, Keith Haring and her boyfriend Jean-Michel Basquiat. Around that time, Madonna's graffiti tag was "Boy Toy", which later used in her professional career, and immortalized their friendship in the song "Graffiti Heart".

Madonna is also an art collector, and was included in the Art & Antiques' 100 Biggest Collectors. In 2001, Madonna lent her Self-Portrait with Monkey by Frida Kahlo at the Tate Modern, which was the first British exhibition dedicated to Kahlo. She is also described as an "art supporter", and Brooklyn Museum acquired two pieces in their collection from funds of the singer. Madonna sponsored various art exhibitions of contemporary artists such as Basquiat, Cindy Sherman and Tina Modotti. Her other art-activities include to co-initiate "Art for Freedom" in 2012, runs the artistic installation X-STaTIC Pro=CeSS (2003) and create the NFT digital artworks, "Mother of Creation" along with Mike Winkelmann ("Beeple") in 2022, receiving a varied reviews by contemporary art critics and journalists.

In the late-20th century, Madonna was widely discussed in the canon of low and high culture in a postmodernist context, mostly through her academic mini-discipline called Madonna studies, and for which she was deemed by some as a modernist. Madonna continued to attract both celebratory and derogatory reviews, while supporters like art historian Kyra Belán acknowledges her impact in the performing arts and other art forms, tagging her as the "symbol for female achievement", Dahlia Schweitzer summed up that many critics have long resisted using the words "Madonna" and "artistic" in the same sentence. Madonna was called a contemporary gesamtkunstwerk and American performing artist David Blaine suggested that perhaps she "is herself her own greatest work of art—something so vastly influential as to be unfathomable".

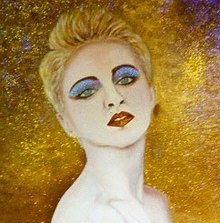

Nicknamed the "Art-pop queen", Madonna is considered to be the "first female pop star to fully engage with the visual elements of her art". She is credited to make routine collaborations with pop artists, while others have placed her as an important figure for reinforcing the connections with the worlds of pop music and art. Her influence is found in various artists such as Mateo Blanco, Trisha Baga and Pegasus. She was also an important medium to the international wide-interest on Frida Kahlo. Several painters and artists have depicted her, in one or more times including the Madonnas of Peter Howson and Alberto Gironella. Her likeness and own works have been featured in art museums and art galleries around the world, including several portraits at National Portrait Gallery, London and in the United States, as well being part of the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection with her video "Bedtime Story". A book called Madonna in Art (2004) documents her impact in the arts, and includes artworks of 116 artists from 23 countries, including Andrew Logan, Sebastian Krüger and Al Hirschfeld.

Background

Early life: formative years

The story of Madonna's origins as an artist is as important as the music itself in understanding the impact she's had [..]

Madonna's background with the arts, and how it influenced her future career, has been documented. In a conversation with curator Vince Aletti, the singer said that her interest in art started as a child because several members of her family could paint and draw, but she doesn't: "I was living vicariously through them", said.[2] She visited the Detroit Institute of Arts, which is how she found about Frida Kahlo and started reading about her, revealing that "one person always leads to another person".[2] Madonna also mentioned her Catholic education, as "there's art everywhere" into the churches, "so you get introduced to it that way".[2]

From early on, Madonna's father encouraged his children to take classes related to art disciplines. He wanted her to take piano lessons, which she tried. While music was on her agenda, the piano wasn't.[3] Madonna had a friend who was taking ballet lessons, and she talked her father into letting her take ballet instead of piano.[3] For Madonna, dance was a gateway for discovery in other arts in which she has maintained a lifelong interest.[4] She studied in the performing arts school dance, music theory and art history. She also took a Shakespearean course.[5]

In Rochester School of Ballet, she met its owner/instructor Christopher Flynn, who took special interest in helping her succeed.[3] Flynn took it upon himself to become her mentor, impressed by her talent and ambition, exposing her to Detroit's museums, operas, concerts, art galleries, and fashion shows.[4][6] One of Flynn's friends commented that Chris knew without ever meeting her family that Madonna lacked any cultural or intellectual background, and yet he was certain that all she needed was someone to take her under his wing.[4] Her tastes broadened to include classical music, Pre-Raphaelite painters, and poets.[4]

Arrival at New York City: late-1970s

Madonna pursued a career in modern dance, moving to New York City in the late-1970s. During her struggling beginnings, she attended for free numerous museums,[2] and worked as a nude model in art schools.[7] This led her to have contact with art photographers as well as painters. Madonna declared: "People painted me all the time".[8] She briefly took classes of photography, painting and drawing.[9]

Personal relationships

Shortly after her arrival in New York, Madonna frequented diverse clubs such as Danceteria, The Limelight, The Roxy, Funhouse, Mudd Club and the Paradise Garage. According to the outlet Contemporary Art, in these places took Madonna's first connection with the art scene in the Lower East Side and SoHo clubs, as these were the same venues frequented by various figures from the art scene, especially those from the School of Visual Arts.[11] Madonna befriended with various painters, graffiti, visual artists such as Keith Haring, Futura 2000, Fab Five Freddy and Daze.[12][13] In 1979, she met graffiti artist Norris Burroughs, with whom had a brief relationship.[12]

Artist Martin Burgoyne, was her roommate on the Lower East Side, and became her best friend.[14] In an interview with Austin Scaggs, she told that a roommate introduced her to Haring, but she was already aware of his art.[13] Her then boyfriend Jean-Michel Basquiat, introduced Madonna to Andy Warhol, Glenn O'Brien, and Larry Gagosian.[13] Gagosian recalled that Basquiat said, "She'll be the biggest pop star in the world".[15] O'Brien later edited Madonna's 1992 Sex book and worked with her on The Girlie Show World Tour book in 1993.[16][17] Madonna met Darlene Lutz through O'Brien, who became her personal art advisor.[18][19]

In an interview with illusionist David Blaine, Madonna talked about the close relationship she had with Burgoyne, Haring and Basquiat, as they hung out together with Warhol joining them sometimes.[14] She further adds: "We found each other, and we connected to each other, and we moved around the city together. They supported my shows. I supported their shows. We were a unit. And I don't even know how it happened. It just did".[13] Madonna further immortalized their friendship in the song "Graffiti Heart" from the Rebel Heart album.[20] Madonna is also mentioned in Warhol's diary The Andy Warhol Diaries.[21]

In 1996, Madonna wrote an article for The Guardian titled Me, Jean-Michel, Love and Money discussing her relationship with Basquiat.[22] She also wrote about her friendship with Haring in the book Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography (1992) by art critic John Gruen.[23] In 2019, Sky Arts' Urban Myths dedicated an episode, Madonna & Basquiat, to their influential relationship. The program marks a "poignant moment" from the year in which Basquiat painted "[the then] most expensive American painting ever sold and Madonna broke through into stardom".[10]

During the spent time with her graffiti artist friends in New York, she used the graffiti tag "Boy Toy", making her own graffiti in walks, subways or sidewalks.[13] The moniker referred to one of her boyfriends, RP3, a subway scratchitti artist who also used the tag and gave it to her.[24][25][26] She later used it as the name of her copyright company, as well as a belt buckle of her dress worn for her Like a Virgin-era.[20] Graffiti artist Michael Stewart appeared as a dancer in her debut music video "Everybody".[27] She continued to collaborate, buying or having a friendship with other artists like the cases of Marilyn Minter and Peter Howson.[28][29] Art critic Hilton Kramer commented about Madonna and Cindy Sherman: "As for their relationship, I think they eminently deserve each other".[9]

Usage of the arts in her work

[Madonna is] perhaps one of the most visually savvy humans on earth.

—David Schonauer, editor-in-chief of American Photo (2000).[30]

Madonna is considered as a visual artist, an one that came from the "video age" with the visuals being an important part of musicians presentation. Canadian professor Karlene Faith echoed "her abundant talent as a visual artist".[31] The Irish Times staff regarded Madonna as "the first female pop star to fully engage with the visual elements of her art".[32] Professor Thomas Harrison at University of Central Florida recognized other female artists before Madonna, but agreed that "[she] took it to a whole other level" as she always embraced the visual aspects.[33]

Madonna's visual artistic image was also vigorously reviewed. Professor Martha Bayles observed that she cultivated a "heavy-duty pop art image".[34] Editor Paul Flynn described that she is "a pop artist in the Warholian sense of the word".[35] John R. May, a professor of English and religious studies at Louisiana State University, asserted that Madonna is a "successful piece of pop art", and is "probably Andy Warhol's dream come to life".[36] He further describes Madonna's image "is a splendor formae of aesthetic as well as moral importance".[36] In Pastiche: Cultural Memory in Art, Film, Literature (2001), Ingeborg Hoesterey from Indiana University, asserts:

Madonna came from the beginning very much from the plastic arts. When she splashed onto the music scene, she did so by quoting the kitsch of devotional Virgin artifacts that (Mexican) figurative painters critiqued in the seventies.[37]

Madonna's knowledges for the arts has been commented. A reporter condescendingly notes that she is an astute if untrained art critic as informed Richard R. Burt.[38] Writing for L'Officiel, Donatella Versace said that because Madonna is "extremely informed" and culturally aware she can hold her own on any subject from music to art.[39] Los Angeles Times critic Patrick Goldstein after a report of Madonna attending Los Angeles County Museum of Art's exhibition "Degenerate Art" (1991), concludes that "she's savvy enough to see the similarities between Otto Dix and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner" but still, "her interests are largely visual".[40] Madonna herself, declared that her primarily interest in art are "suffering, and irony and a certain bizarre sense of humour".[9]

Madonna's knowledges for fine-art photography and other styles of photographies have been commented. British art historian John A. Walker, cited her "knowledgeable about photography".[9] Curator and photography critic Vince Aletti, commented that her works "are filled with knowledgeable photographic references".[41] In a general sense, English writer Andrew Morton in his book Madonna, wrote that her stunning visual sense is no accident; Madonna has spent a lifetime studying photographs, black-and-white movies and paintings.[42]

As an influence on her

| External videos | |

|---|---|

"Bedtime Story" (1995) briefly the most expensive music video in history, shows references of numerous surrealists.[43] Is part of Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection.[44][45] | |

Naturally, Madonna has taken inspiration from the worlds of cinema and art, and is reported to often inspired by the visual artists she collects.[46] At some point of her career, she claimed: "Every video I've done has been inspired by some painting or work of art" (including photographs).[47][9] The conceptual art video "Bedtime Story" marked alone, a reference of multiple artists and surrealists such as Frida Kahlo, Man Ray, Remedios Varo, Tamara de Lempicka and Leonor Fini.[43] Staff of Decades commented that "art wasn't just part of her personal life, but her professional one too".[48] In 2020, she revealed: "Art has kept me alive".[49]

Various observers have commented Madonna's influence from other artists. Pamela Robertson from University of Notre Dame writes that although he influenced Bowie and Reed, "his true heir is Madonna. She captures the full force of Warhol".[50] French academic Georges-Claude Guilbert further describes he's "virtual father of Madonna".[50] Scholars Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar agreed in that "the work of Cindy Sherman prefigured Madonna's style in the art world".[51] Glenn Ward, wrote in Understand Postmodernism: Teach Yourself (2010) that "Madonna's work can be compared to that of the American artist Cindy Sherman".[52] A portrait of Lee Miller kissing another woman by Man Ray that she owns, inspired her and encouraged the use of lesbian imagery.[9]

Walker, the British art historian observed that Picasso was a precedent for Madonna's reinventions as he was an artist who changed his style a number of times.[9] Madonna herself stated in 2015: "I like to compare myself to other kinds of artists, like Picasso". Along with this, she believes there is not a time or expiration date for being creative. Like Picasso, she says "he kept painting and painting until the day he died".[53] In an interview with Vice that year, she said: "I want to live forever, and I'm going to" (through her art).[54]

Collaborations with artists

- N.B. This section only includes a brief description

Madonna has collaborated with various painters, visual artists. Her friend Martin Burgoyne designed and draw the cover of single "Burning Up", featuring a grid of twenty postage stamp-sized portraits of Madonna in every color of the rainbow.[55] Her brother, Christopher Ciccone became the art director of her tours Blond Ambition World Tour and The Girlie Show.[56]

Street artist Mr. Brainwash entered the music scene when Madonna commissioned him to design the cover art of Celebration. Overall, he designed 15 different covers to the wide release, including singles, a video compilation, and a special edition vinyl.[57] Brainwash collaborated again with Madonna, in the opening of her Hard Candy Fitness in Toronto, with a live on-site creation of an 11 by 30-foot Madonna mural.[57] In 2017, Madonna invited Brazilian street artist Eduardo Kobra to paint two murals at the Mercy James Institute for Pediatric Surgery and Intensive Care.[58] In 2012, she participated in a contest sponsored by Johnnie Walker in Brazil, in which she chose graffiti artist Simeone Sapienza as the winner to create the artwork of her single "Superstar".[59]

Brazilian visual artist Aldo Diaz was hired by Madonna to works on the covers of her single "Bitch I'm Madonna" and the Rebel Heart Tour. As well, for the catalogue of her Madonna: Tears of a Clown and her official 2018 calendar.[60] According to Artnet, American visual artist Marilyn Minter have collaborated with Madonna.[61]

She has also collaborated with fine-art, portraits and fashion photographers, and many of them took Madonna as their muse. Steven Klein described her: "Madonna's always been more of a performance artist to me".[62]

Madonna's footprints in the art scene

Within the art world, Madonna is almost as well known for being a collector as she is for her music.

—Lani Seelinger from The Culture Trip (2016).[63]

Madonna made several appearances in the art scene. In this regards, Kriston Capps from New York magazine said that "Madonna has arguably been edging around the corners of contemporary art her entire career".[64] In 2016, Rain Embuscado from Artnet commented that she "has always had a hand in the art world".[65] British art historian, John A. Walker have documented her life and career in the perspective of the arts.[9] In 1990, the arts-based BBC1 series Omnibus broadcast a profile on Madonna watched by 7.7 million people, which was slightly higher that the average audience of 3.1 million.[66]

Activities and contributions

In 2001, she presented the Turner Prize at Tate Britain in London, receiving positive comments from BBC's art correspondent, Rosie Millard.[68] It was called as "a rare marriage of pop and art".[69] British linguistic Roy Harris described: "The merger between art and showbiz is symbolized by the choice of Madonna".[70] Peter Leese from Jagiellonian University, said that "the fashionable status of the new art was confirmed when Madonna came to London to host the awards ceremony".[71]

In 2014, she presented the Innovation Award of The Wall Street Journal at MoMA to her former dancer, Charles Riley for his contributions to the performing arts.[72] In 2017, she was the special guess with visual artist Marilyn Minter at the A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum in its special segment Brooklyn Talks: Madonna x Marilyn where both addressed topics of art and culture. The event was moderated by Anne Pasternak, Elizabeth Alexander, Shelby White and Leon Levy.[73]

Alex Greenberger from Artspace confirmed that Madonna has also made art.[74] In 2003, Madonna created the art installation with Steven Klein called X-STaTIC Pro=CeSS shown at international art galleries such as Deitch Projects, Gagosian Gallery and Camera Work in Berlin.[74][75] The multimedia exhibit was touted as "Madonna's art world debut".[76] According to art critic Walter Robinson, the installations were priced at $35,000–$65,000, with a copies of the catalogue, printed in a run of 1,000 units, at $350 plus taxes.[77] Robinson describes the project "too cheesy to be art [but] philosophically speaking, no slight accomplishment in art world that privileges everything".[77] To English writer Lucy O'Brien, is one of Madonna's most fascinating projects and saw her in a new phase with her utilization of visual art.[62]

In 2013, Madonna co-initiated "Art for Freedom" with Vice, as an effort to support independent creators of art content around the world and to promote and facilitate artistic and free expression, giving a monthly award to an budding artist.[78][74] Essayist Lisa Robertson commented that Madonna became in a curator in the "stricter sense".[79] Madonna appeared at Gagosian Gallery in New York, to mark the launch of the initiative, with a performance showing the singer bound, handcuffed, and dragged onstage by performers in police uniforms.[64]

In 2022, along with digital artist Mike Winkelmann ("Beeple"), Madonna created a NFT project called "Mother of Creation" consisting of three videos, namely "Mother of Nature", "Mother of Evolution" and "Mother of Technology",[80][81] Launched in the NTF platform SuperRare,[82] each of the digital artworks are accompanied by music and a voiceover by Madonna, who reads poetry by Persian poet Jalaluddin Rumi and spent, apparently one year in making the project.[83][84] The project became a subject of scrutiny,[85] and Gareth Harris from The Art Newspaper said about this collaboration: "There have been stranger collaborations in the art world, but not many have been as headline-hitting as the newly minted partnership between Queen of Pop Madonna and 'Beeple'".[83] Art magazine Apollo, were "delighted by what passes for an expression on the face of Madonna of the NFT".[82]

Art exhibitions

Madonna's presence at the museum is an instance of the implosion of high and low culture that has generally been regarded as both the end of a modernist aesthetic and its displacement and sublimation by a postmodern, multicultural aesthetic based on identity politics, oriented toward performance.

—Richard R. Burt about Madonna at Los Angeles County Museum of Art's exhibition "Degenerate Art".[38]

Madonna was part of various art exhibitions, sponsoring various of them. In The Legacy of Colonialism (1998), Máire Ní Fhlathúin said that Madonna "has quietly sponsored many exhibits over the years", and for this part, her curator Darlene Lutz explained: "Madonna doesn't want or need the press for everything she does".[86]

In 1992, she provided funding for the first museum retrospective for Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[87][88][11] In 1995, she sponsored the first major retrospective of Tina Modotti at the Philadelphia Museum of Art which curator and art historian Anne d'Harnoncourt commented: "She seemed a natural sponsor for an exhibition that introduces the artist to a broader public" (Modotti was considered to be a lesser-known artist).[89] Kristine Ibsen from University of Notre Dame said that the exhibition was possible thanks to "a generous donation by Madonna" and occurred just a few months short of the centennial of Modotti's birth in August 1896.[90] In 1996, Madonna sponsored an exhibition of Basquiat's paintings at the Serpentine Gallery in London.[91] Madonna was the only sponsor for the Cindy Sherman's first retrospective Untitled Film Stills at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1997.[92][93][94]

She has visited numerous museums, including various attendances at MoMA launch parties,[46] and at Tate galleries while she lived in the United Kingdom.[95] For the latter museum, she lent her Kahlo's Self-Portrait with Monkey at Tate Modern, which was the first British exhibition dedicated to Frida Kahlo.[96][97] The decision to loan the painting only came after several weeks of negotiation and partly delayed due the September 11 attacks.[96][95] Jennifer Mundy, curator of the exhibition, expressed: "Clearly something about this show persuaded Madonna to lend".[95] Commenting on the loan, Madonna said: "Loaning my Frida to Tate is like letting go of one of my precious children, but I know she will be in good hands and the exhibit would not be complete without her".[96]

Art collecting

Madonna is an art collector with a collection at worth of $160 million as of 2013, according to website Artspace.[74] Other estimations include $100 million, at least since 2008.[98][99] Artnet deemed her possessions as a blue-chip collection.[100] Madonna started to collecting after receiving her first paycheck in the early-1980s and eventually hired Darlene Lutz as her personal art dealer, who worked with her from 1983 to 2004.[101][46][18] Darlene along with Madonna's brother Christopher Ciccone bid at auctions on her behalf, with a budget no larger than $5 million.[98]

Her collection is based primarily on modernists,[100] and include over 300 pieces of artists such as Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger and Frida Kahlo.[99][74] She also acquired works by Old Masters, including Italian painter Master of 1310.[18] Austin Scaggs asked Madonna if she has paintings of her friends Warhol and Haring and her former boyfriend Basquiat. She responded that "have a few of each".[13] In a 2015 interview with Howard Stern, Madonna revealed that Basquiat took back the paintings he had gifted her and destroyed them, painting over them black after she ended their romantic relationship. She regrets giving the art back, but "felt pressured to do so since it was something he had created".[102] In 2021, she posted a series of photos of herself at home with a Basquiat drawing of her portrait.[103] Madonna also collects artistic portrait pictures. In the 1990s, she paid $165,000 for Modotti's Roses then the highest price ever commanded by a print at auction.[89][104]

Morton explained that her collection means so much to her that she would rather be remembered as a modern-day Peggy Guggenheim than as a singer and actress. Madonna was quote as saying: 'Paintings are my secret garden and my passion. My reward and my nice sin".[42] Madonna appeared in the 100 biggest collectors by Art & Antiques (c. 1996), and in the Top 25 Art Collectors by The Hollywood Reporter in 2013.[105][99] A spokesman of Tate Gallery, called her a "distinguished art collector".[69]

Art supporter

The work Untitled (1985) by American painter Julia Wachtel and The Six Second Epic (1986) by Kenji Fujita were bought by Brooklyn Museum with funds of Madonna "Ciccone Penn".[106][107] Madonna has been regarded as an "art-lover",[69][95] and is known also as a supporter of modern art.[108] According to Tate Gallery, Madonna has a long-standing interest in contemporary British art.[69] Anthropologist Néstor García Canclini recognized Madonna's support for feminist art.[109] Madonna's Los Angeles home was reported to be a lived-in modern art museum.[21]

Christopher Ciccone wrote in Life with My Sister Madonna that Madonna commented on his artworks: "I like them, you should keep on painting", and Ciccone said that "her encouragement means a lot to me".[110] Ciccone later reported that her sister lent him $200,000 to buy a studio where he began to paint regularly.[98] In an interview with artist David Blaine in 2014, she informed that one of her son was interning for French street artist JR.[28]

During the Rebel Heart era, she invited her fandom in an online contest, to create fan arts in order to showing them in her Rebel Heart Tour as backdrop videos.[111] Some of them, became part of an art exhibition in Italy at the Palazzo Saluzzo di Paesana titled Iconic – Portraits & Artwork inspired by The Queen curated by Gabriele Ferrarotti and Ettore Ventura with 50 pieces chosen by Madonna from 20 artists around the world.[112]

Madonna supported various unknown artists, exposing their works in her social media or buying some of their artworks. She posted the murals with her image depicted by Greek graffiti street artist, George Callas,[113] the Montreal-based street artist MissMe,[114] and Brazilian visual artist Aldo Diaz.[60] Madonna also showed support to the impressionist painter Rhed, the pseudonym of his son Rocco with British filmmaker Guy Ritchie before his identity was revealed.[115] After his identity was confirmed, art critic Jonathan Jones suggested "that the artist had been put into the public eye too soon".[115]

Madonna bought her image depicted by Spanish painter Jesús Arrúe called MadammeX. She later showed one of his works on Instagram, depicting Vladimir Putin and Adolf Hitler as a representation of the Russo-Ukrainian War. The post went to become "viral".[116] In a similar situation, Scottish artist Michael Forbes, gained international notoriety according to some outlets when Madonna shared online his satirical painting depicting Donald Trump as King Kong with her as the Statue of Liberty.[117] Forbes expressed he featured Madonna because of his admiration and influence within the gay community in the US.[117]

Art for charity

She also used art for charity. In 1991, a canvas painting created by Madonna went to a charity auction that was ultimately bought by actor Jason Hervey.[118] She hosted a family art sales with two of her children to raise money in benefit victims of the 2020 Beirut explosion.[119]

In 2013, Madonna sold the 1921 work Three Women at the Red Table of Fernand Léger which she bought in 1990 for $3.4 million, raising $7.2 million. This was in support of female education through her Ray of Light Foundation.[120] This action by Madonna was reported as a combination of her passions for art and education, with the singer declaring: "I cannot accept a world where women or girls are wounded, shot or killed for either going to school or teaching in girls. I want to trade something valuable for something invaluable – Educating Girls!".[121] When her project "Art for Freedom" was operating, she donated $10,000 each month to a nonprofit organization of a featured artist's choice.[122][74]

In 2016, during her gig of the Madonna: Tears of a Clown at the Art Basel, Miami held an art auction to benefit Madonna's Raising Malawi foundation, as well as art and education initiatives for impoverished children in the country. She auctioned some of her art collection, including paintings of Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin. Combined with other personal belongings, she raised more than $7.5 million.[123][124] Her NFT project with "Beeple" generated primary auction sales volume of $612,000, destined to three charities picked by Madonna and "Beeple".[85][84]

Controversies

Madonna created controversy when she presented the Turner Prize in 2001 to Martin Creed and told the audience: "Right on, motherfuckers— everyone is a winner!". Art historian James Elkins cited Glyn Davis' comment in Is Art History Global? (2013) about this event: "It would, of course, be inappropriate to see this as a radical intervention in art historical discourse. However, the clash of Nicholas Serota and pop icon Madonna produces its own pleasurable frisson; seeing a woman talk about art on television remains a rare sight, and it always to be welcome".[126] British art historian, Julian Stallabrass was convinced that the intention without doubt of having Madonna announce the Tate's Turner Prize in 2001, was to raise the profile of the event further. However, Stallabrass stated that the effect and the art displayed took on the role of more or less interesting diversions to the main spectacle of the "singer's publicity-hungry misbehaviour".[127]

Madonna's NFT videos produced along with "Beeple", were criticized as features the singer fully nude in a digitalized 3D Madonna character, while giving birth to butterflies, trees, and insects such as robotic centipedes through an actual scan of her genitals.[84] She defended the project saying: "I'm giving birth to art and creativity".[128] American art critic Ben Davis took issue with the Madonna figure.[83]

Madonna also received criticism when she refused to loan a rare Frida Kahlo painting to the Detroit Institute of Arts.[129] Cultural critic Vince Carducci in one conclusion said that "my suspicion is that the request never bubbled up to her".[130] Art journalist Lindsay Pollock said that could not understand why Madonna "has no love" for Andreas Gursky after a report that a work that he gave to the singer was on sale at Sotheby's.[131]

Performing arts (+ impact)

It's pretty much impossible to deny Madonna is the modern master of performance art

—Samuel R. Murrian from American nationwide magazine, Parade (2022).[132]

Kyra Belán, an art historian and professor from Broward College said that Madonna has achieved major success as an artist within several art forms further nothing that she has impacted the performing arts and became the symbol for female achievement in all these areas.[133] Madonna was also suggested as the first who marked the passage from "performativity" as a way of doing to away of being.[134]

Professor Paul Rutherford of University of Toronto deemed her a visual performer with an "extraordinary stage presence".[135] Associate professor Patricia Spence Rudden at City University of New York noticed that the performance art aspects of Madonna feature in a wildly discursive essay by Jane Miller, while her performances are look as postmodern by Mark Watts.[136] Scholars of University of Macerata, concurred that Madonna has constructed an innovative "poetics of performances" that has been studied by numerous sociologists around the world.[134] They agreed that her character does not indicate so much a musician, but a performer, which they further described her as an "iconic performer".[134] Canadian professor Karlene Faith, agreed in that her videos and live performances, reveal "an uncommon conceptual and artful imagination".[137] Conversely, Catherine Schuler in Women in Russian Theatre (2013) wrote that some "avant-garde critics regard her performances as trendy scholock rather than legitimate art".[138]

Stage shows

Author Jason Hanley, commented that her performances made critics and scholars "stand up" and take note of her sound, style and message.[139] Madonna's performances are considered to be an organized sequences of events, scripts, known texts and movements.[134] Examining her influence in the arts, an author qualified her stage performances as tableaux vivants. Music critic Michael Heatley held that she "had always set high standards with her stage shows".[140] Senior lecturer, Ian Inglis opined that her live performances have been celebrated as "theatrical events",[141] while others deemed them as "immaculate performances".[142] Writing for Slant Magazine, Sal Cinquemani deemed her as "the greatest performer of our time", saying that she is a showgirl and her shows have always been theatrical with narrative storytelling.[143]

Madonna's performances are art, after all—art that incorporates a play of sometimes conflicting social and political ideas

—Paul Thom, dean of arts at Australian National University (2000).[144]

Madonna is commonly credited by authors to normalize multiple concepts of stage shows and tours. Lester Fabian Brathwaite of Logo TV, explained that "she's transformed the concept of a rock concert from a mere live show into true performance art".[145] Fashion journalist, William Baker mentioned that "the modern pop concert experience was created by Madonna really".[146] Another observer commented that everything is bigger on a Madonna tour.[143] Scholars from Berrin Yanıkkaya to writers like Matt Cain have concurred she paved the way of extravaganza in concerts as a theatrical spectacle in which the female music artist is placed centre stage.[147][148] According to Smithsonian Institution, Madonna transformed pop concerts into dance spectacles, and she popularized the use of the headset microphones to allow greater movement and used choreography.[149] They further explained, Madonna is the first performer to user her concert tours as reenactments of her music videos.[149]

If a specific title is mentioned, it is generally the Blond Ambition World Tour; Jacob Bernstein of The New York Times cited previous examples like Donna Summer or Michael Jackson, but Madonna's 1990 tour "was bigger, bolder and more imaginative" for which she set the tone and the bar of modern megatours.[150] According to Mark Savage from BBC, Madonna also raised the bar for stadium-sized spectacle.[151] Other critics noticed that Madonna divided her performances into "thematic categories", and this was unusual for concerts including from a creative level.[152] In Baker's words, the splitting of sections derived that pretty much everyone copies or everyone is inspired by.[146]

Video art and production

In regards her scholarly analysis, much of her scrutiny was concentrated to her music videos, and she became in "the most analyzed" figure from the rest of female music video performers.[153] The analysis of her music videos, indeed, played a fundamental role in the initial wave of interest in her.[154] Critic Martha Bayles, said that in the video age, was more important one's relation to the visual arts instead one's musical statement. She said, that is why pundits, professors and preachers go cross-eyed trying to interpret Madonna, taking her far more seriously than others.[34]

Professor Rutherford commented that videos are part of her visual presentation, and shows her artistic renditions.[135] He further adds that she has put considerable time and money into crafting what were often very elaborate productions, investing million dollars (she has several pieces among the most expensive videos in history).[135] She has worked with numerous photographers, directors and videomakers.[155]

Madonna is commonly credited as "the first female artist to exploit fully the potential of the music video", a statement included in her profile at Encyclopædia Britannica written by Lucy O'Brien.[156] Professor Norman Fairclough suggested that "the evolution of the music video could indeed be studied through Madonna".[157] Armond White credited Madonna to even popularized the music video.[158] Sarah Frink from Consequence mentioned Michael Jackson, but she also suggests that it was Madonna that helped set the standard for the music video.[159]

Some scholars noted that Madonna's music videos are not merely commercial products, as they are visual performances where the music functions as the soundtrack.[134] White explored Madonna's usage and impact in the videos as an art form, adding that she "elevated this into a memorable expressive art form".[158] He further adds, that Madonna's concepts led some artists to have "art-consciousness" such as Björk or Lady Gaga, further adding that "they'll never repeat the moment when Madonna's connection to the zeitgeist became historic".[158]

Dancing

As she moved to New York to pursue a career in modern dance, choreographer Richmond Talauega said "the thing that separates her from everyone else is that she started off as a dancer".[160] According to Rolling Stone, she is "entirely synonymous with dancing".[161] Even, from this association "others have considered that her role as a musician and producer is secondary to her role as a dancer" according to professor Thomas R. Harrison of Jacksonville University.[162] Scholars and dance critics have reviewed Madonna through this artistic discipline, with American sociologist Cindy Patton being one of the first in articulate the cultural and proto-political effects of dance culture with Madonna.[163] In 2015, dance critic for The Guardian, Lyndsey Winship commented that "dance, from serious art to club trends, is still at the heart of Madonna's live shows".[160]

Madonna is reported to taken inspiration also from the underground such as club culture, gym culture to martial arts and the avant-garde.[155][144][164] Included in Rolling Stone's poll "10 Favorite Dancing Musicians", Madonna was credited by them to help bringing many underground dancing or its elements into the mainstream culture.[161] Publishing company, DK noticed her influence in dance styles such as voguing and krumping to the point that she made them "globally popular".[165] Such was the influence of Madonna in voguing, that has largely been perceived as the inventor of this dance style.[166] Similarly, a 1994 article of Public Culture, said the gay ball dance form was popularized by Madonna "in a way that made it seem like she practically invented it".[167] After Madonna's 2012 performances, David Graham from Toronto Star, wrote that with the assistance of Madonna, "slacklining gets a bounce in popularity".[168] Others credited Madonna, in "innovating" rave culture.[169]

Madonna is also suggested to pioneering lip synching and extensive choreographies in the video format.[170] In this regard, Rutherford agreed in that many of her videos featured dance, either Madonna alone or Madonna and a troupe of mostly male performers.[135]

Depictions and accolades

According to English writer Andrew Morton several of her films have been exhibited in museums around the world, notably the Pompidou Center in Paris, as modern works of art.[42] In 2016, MoMA PS1 screened Madonna: Truth or Dare celebrating its 25th anniversary and its impact, including the arts.[171]

Her music videos has been part of art exhibitions as well, and this include «Bedtime Story» displayed in permanent exhibitions at Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and then in Museum of the Moving Image of London.[44][172] Other entities like the School of Visual Arts screened the video too.[173]

In 2018, Madonna was awarded by the High School of Performing Arts in Malaga (in Spanish: Escuela Superior de Artes Escénicas de Málaga, ESAEM) and they rendered a performance tribute called Madonna Revolution.[174]

-

Multidisciplinary Canadian artist Clara Furey at the Festival TransAmériques in Justify a Madonna-inspired art performance

-

Performing artists Amelia Emma Forrest (left) and Sara Fernandez Cuevas (right), in the performance Madonna

Artistic reception

Postmodernism

Postmodernism encompasses several ways and movements, including aesthetics. In this sense, professor Arthur Asa Berger said that "much has been said of her 'postmodernism'" and it was a time popular discussing Madonna in some academic circles in this context. Berger further explains that a simple way of thinking about postmodernism is as the way in which "our contemporary artists and culture produce art".[175] English writer Lucy O'Brien held that "much has been made of Madonna as a postmodern icon", as well her reference points have been resolutely modernist.[176]

In the 20th and throughout 21st centuries, Madonna has been placed high in a postmodernist context. American philosopher Susan Bordo described her as a "postmodern heroine".[177] She is suggested by assistant professor Olivier Sécardin of Utrecht University to epitomize postmodernism.[178] Christian writer Graham Cray gives his point of view saying that "Madonna is perhaps the most visible example of what is called post-modernism",[179] while for Martin Amis she is "perhaps the most postmodern personage on the planet".[179] Academics Sudhir Venkatesh and Fuat Firat deemed her as "representative of postmodern rebellion".[178] Within this perception, author Glenn Ward justified that "Madonna has been important to postmodernism for her ability to plunder the conventions".[180]

Criticisms and ambiguity

Her enormous commercial success is often held against her [...] as evidence that she prostitutes her art (and, by extension, herself).

—Genders, academic journal of University of Texas Press (1988).[181]

Dahlia Schweitzer, said that many critics have long resisted using the words "Madonna" and "artistic" in the same sentence.[182] Sandra Barneda from website The Objective, observed that for many she is far from art.[183] In 2019, Michael Love of Paper gives a general picture saying that both her music and visuals "have always been interpreted as 'good' or 'bad' based on what's relevant in the moment".[184]

Three academics concluded throughout a survey responded by college students in the early-1990s, that Madonna "is seen as all artifice and no art" and "as emblematic of the lowest form of aesthetic culture".[185] It was also addressed that "Madonna's art also is suspicious because, unlike the works of Vincent van Gogh or Henri Matisse, it is readily available for purchase at any record or video store" thus "she is not part of a high art tradition of selfless".[185]

Art critic John Berger also agreed that such availability (of her works to a mass public) may contribute to reducing the perceived value of Madonna's work.[185] In this aspect, academic Douglas Kellner suggests that Madonna should be interpreted in terms both of her aesthetic practices and her marketing strategies, and her works can thus be read either as works of art, or analyzed as commodities that shrewdly exploit markets.[186] In a general sense, a 2009 article from Billboard describes that "Madonna is an artist that wants to reach the most people she can and do it in very creative ways".[187]

In ambiguous views, Kriston Capps from New York commented that Jeff Koons made conspicuous consumption a concern of fine art, but Madonna immortalized it with "Material Girl".[64] Italian art critic Achille Bonito Oliva said the song was perfect for a time when art, money and politics were electronically entwined.[188] Simon Frith cited three scholars-survey that "clearly, pushing Madonna to the bottom rungs of the pop cultural ladder makes a space at the top for pop music 'art'.[189]

The fact that her work could provoke such a lively debate was surely a sign of its cultural significance, if not of its high aesthetic value.

—British art historian John A. Walker, about the reception of Madonna's broadcast profile (1990) in the arts-based BBC1 series Omnibus.[66]

Her first publishing work, Sex was considered an art book. Outlet Contemporary Art pointed out that by "bringing together arty images" the book raises interesting questions of when is it art and acceptable.[11] In Madonnaland, Alina Simone denotes that "her art is highly sexualized because she is highly sexualized".[24] As editors of compendium The Madonna Connection (1993), puts it, saying that Madonna's failure to conform to established rules and commentary have led to her dismissal as a serious artist and fueled attacks on her.[190] Academic Michael Ignatieff, expressed "I certainly don't mind that she is obscene [...] What I can't stand about Madonna is that she thinks she's an artist".[179]

Her broadcast profile as an artiste in the arts-based BBC1 series Omnibus attracted criticisms and according to art historian, John A. Walker, "letters and articles subsequently appeared in the press both for and against Madonna".[66] Michael Ignatieff claimed that Madonna's conception of art was false, that she was not a serious artist.[66] Prior years, in 1988, professor of media arts John Ellis questioned in magazine Modern Painters about the idea of having Madonna in Omnibus.[191]

Madonna has been described as an iconoclast, mainly from religious views. Mexican painter, Francisco Toledo regrets that more people search and are more interested in the singer that in the Sistine Madonna.[192]

Alternative views or counter-suggestions

In On Fashion (1994) by scholars Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferriss, it was concluded that Madonna challenges and "puts in question and tests one's aesthetic categories and commitments", but she can be viewed as a modernist.[193] Walker, the British art historian proposes that "there are few art forms and artists capable of providing such exhilarating experiences and this is why Madonna has attracted so many".[9] He further prompted that it is evident "she fully understands that art depends upon artifice, creation, invention, imagination and masquerade".[9]

Scholar Pamela Robertson from University of Notre Dame addressed that "Madonna's art and its reception by critics and fans reflect and shape some of our culture's anxieties about identity and power inequalities".[194] American musicologist Susan McClary, provides arguments in her area to refute some accusations towards Madonna, saying that the singer exercises over her art, its production, and in particular, her identity. McClary, explains that the framework in which Madonna operates is somewhat different to that of the Western art tradition in which feminine subjects associated with desire (Carmen, Isolde, Salome, Lulu) must be destroyed.[195] Despite her controversial agenda, in 1990, critic Jon Pareles invited audience to see her as a "continuous multi-media art project".[196] Writing for martial arts magazine, Black Belt editor Sara Fogan observed that Madonna "challenges herself as an artist".[164] Italian professor Massimiliano Stramaglia gives also a sympathetic view saying that "Madonna is not a common artist, but a hypertrophic system of signs and symbols bound to the worlds of spectacle, art, music, cinema and fashion".[134]

Recognition

She is the perfect example of the visual artist, noted graffiti artist and cultural commentator Fab Five Freddy.[42] Following Michael Jackson's death, a panel of Argentines art critics deemed her at that time as "the only universal artist left standing". Those critics, including Daniel Molina, Graciela Speranza and Alicia de Arteaga explained that she is herself "a multimedia expression that condenses fashion, dance, photography, sculpture, music, video and painting".[197] She has been criticized by others musical fellows, but also applauded by others. In the latter group, Kanye West commented: "Madonna, I think, is the greatest visual musical artist that we've ever had".[198]

Madonna was quoted saying: "I am my own experiment. I am my own work of art".[199] Writing for Interview, American illusionist David Blaine suggested that perhaps she "is herself her own greatest work of art—something so vastly influential as to be unfathomable".[14] John R. May, a professor of English and religious studies at Louisiana State University concludes that the singer is a contemporary gesamtkunstwerk becoming a work of pop-art herself.[36] Scottish music blogger Alan McGee proposes that she is "post-modern art, the likes of which we will never see again".[200]

Influence

According to Stephanie Eckardt from W, her impact and influence in the arts "has been made almost entirely behind the scenes".[28]

One of the mains impact of Madonna in the arts, is the connection with pop stage. Madonna is credited to make routine collaborations with pop artists.[201] In this regard, Eckardt said that the singer pioneered the crossover between pop and art by hanging with the likes of Warhol, Basquiat or Haring.[28] On the same plane, editors of Enciclopedia gay recognized Madonna's footprints in several field of arts, concluding that no artist has done as much to push the boundaries of pop music into the art world.[202] Marissa G. Muller from W also concurred that Madonna bridged the worlds of pop music and fine art.[201]

Ana Monroy Yglesias from the Grammy Awards website called her the Art-pop queen.[203] For Mark Bego, she has "turning everything she touches into classic pop art".[204] On the other hand, Madonna has brought art to the streets herself in a way too.[28]

Impact and influence on other painters and visual artists

For me, Madonna has became even more important than any art movement in terms of history and popular culture

—Silvia Prada in Dazed's article: "Madonna interpreted by contemporary artists" (2014).[205]

Madonna's influence is found in numerous contemporary artists. In 2014, curator Jefferson Hack dedicated an article in which she was "interpreted by contemporary artists" with portraits in art forms and their feelings about her.[205] Furthermore, as Madonna took inspiration from others artists (usually those from she collects), music journalist Ricardo Pineda, conversed with EFE and concludes that her mentions and references is favourable for their legacies.[206]

Mateo Blanco, commented: "Madonna has always been a great inspiration to me".[207] It was also reported that American installation artist Trisha Baga has a "longstanding fascination" with Madonna that "is often manifested in her work".[208] Pegasus told Evening Standard that he always listens to Madonna as he works and his work "tends to have elements of her character".[209]

Several lesser-known artists were reported to be influenced by Madonna. They received press coverage after Madonna showing their works. In terms of influence, Greek Reporter said that Greek graffiti artist George Callas has a "creative obsession" with her.[113] Madonna has always been an inspiration for Spanish painter Jesús Arrúe.[210] Brazilian visual artist, Aldo Diaz, whom also collaborated with her, reported her as an influence in his career, and thanks to her interest in Madonna, he began to study photography, arts and became in a graphic designer.[60] Most of them have depicted her.

Impact on Frida Kahlo cult

Madonna's attracted media headlines when revealing her interest in Frida Kahlo during the 20th century, a relatively lesser-known artist in the international stage in areas like popular culture. In this regard, Andrew Morton reflected: "How many pop singers have ever heard of Frida Kahlo, for example, let alone wanted to make a movie about her?".[42] Janis Bergman-Carton devoted a scholarly article for Texas Studies in Literature and Language where discusses the relation Kahlo-Madonna, and how "become part of standard journalist reportage on both women" of around years.[211] In her critical study, Bergman-Carton prompted that "the reciprocity resonates in box offices, museum coffers, record companies and the art market".[211]

A great variety of agents, from art critics to mainstream media have deemed Madonna as an important medium for the further wide-interest on Kahlo. The Daily Telegraph staff credited Madonna to transform Kahlo into a "collector's darling".[212] British art historian, John A. Walker, commented that partly due to Madonna, the Mexican painter became a posthumous celebrity not only in the domain of art history but also in popular culture.[9] Canadian art historian, Gauvin Alexander Bailey also concurred that she helped in turn a widely interest in the artist.[213] Historian Hayden Herrera added that the mention of Madonna sets the tone for the entire piece.[214] Mexican art magazine Artes de México staff also discussed the importance of the singer for the "Fridomania".[215] According to El Sol de Tampico, Alejandro Gómez Arias (a former Kahlo's boyfriend) gained some attention because of Madonna.[216]

Other areas

Her own academic discipline Madonna studies saw a framework in liberal arts education, along that during the 20th century, Madonna was at the center for a while of the debate between pop and high culture in a postmodern context.[217] The 2000 article Madonna and Hypertext, published by the National Art Education Association in their Studies in Art Education, explored two Madonna's videos.[218]

At least one of the books about Madonna have devoted the content to her figure as an art subject; Madonna In Art (2004) which compiled portraits and paintings of the singer by over 116 artists from 23 countries, including Andrew Logan, Sebastian Krüger, Al Hirschfeld, and Peter Howson.[219] The book that contains over 244 artworks and 190 pages, is noted by its author as a "tribute to Madonna and her remarkable career in art".[220]

Artistic depictions

Naturally [...] many visual artists have been inspired to depict Madonna.

—British art historian John A. Walker (2003).[9]

Numerous artists around the world have depicted Madonna, either one or more times. Scottish painter Peter Howson, which dedicated numerous pieces to Madonna, commented: "She's a subject everyone is drawn to".[222][29] Scottish academic Alan Riach, explained that the Madonnas of Howson address the question of assertion, of strength and power.[223] Mexican painter Alberto Gironella devoted almost all his works in his last years to Madonna, or taken inspiration from her, describing that "more than pop [she] is the last surrealist".[224] Gironella was reported to have an "obsession" with the singer,[224][225] described as an amour fou by an outlet from the National Council for Culture and the Arts in Mexico.[226] According to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Monterrey his Madonna series artworks, started in 1991.[227]

According to portal Universo Online, Madonna became for a while in a muse for her boyfriend Jean-Michel Basquiat, who depicted her in his art.[228] His painting A Panel of Experts was in part inspired in his lovers, Madonna and Canadian painter Suzanne Mallouk.[229] Madonna reported that Andy Warhol and Keith Haring did four pieces for her as a gift for her wedding with Sean Penn.[13]

Spanish plastic artist, Mikel Belascoain created the first art building of Pamplona, capital city of Navarra, Spain with several paintings of Madonna called Madonna 1986. Belascoain reported to be more interested in Madonna as an artist than Marcel Duchamp.[230] In 2005, South African artist Candice Breitz created Queen (Portrait of Madonna), a multichannel video installation featuring 24 Italian Madonna fans performing their way individually, through Madonna's The Immaculate Collection album on a grid of monitors. It has been exhibited in museums like SCAD Museum of Art or Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Art critic Roberta Smith of The New York Times commented positively towards this artwork.[231]

In Madonnaland, Alina Simone explained that graffiti artist Adam Cost had begun wheat pasting his "Cost Fucked Madonna" mantra all over Manhattan in the 20th century. Simone discovered that "Cost" was his pseudonym, and his stickers "Cost Fucked Madonna" became an underground catch-phrase in the 1990s, spurring a healthy trade in knock-off T-shirts and other merchandise. Following his comeback after his arrest, "Cost Fucked Madonna" posters began reappearing on the streets of New York in 2012.[24]

Other artists that have depicted Madonna and been documented by media outlets include Peter Blake,[232] among many others.

Selected gallery (Notable works or artists)

-

Madonna by Paul Harvey

-

Nathan Wyburn elaborating a toast portrait of Madonna

-

Life is Beautiful by Mr. Brainwash

-

A political cartoon of Madonna by Carlos Latuff

-

Oil painting by Rajasekharan Parameswaran

-

Madonna by Oscar Casares

-

A wheatpaste by Adam Cost

-

Madonna as part of the 100 Faces of the Tenerife Auditorium by Bulgarian artist Stojko Gagamov

Art exhibitions and museums depictions

French academic Georges-Claude Guilbert noticed that her likeness has been exhibited in museums.[232] Madonna is represented at the National Portrait Gallery, London and in United States with various portraits; David Tetzlaff, a media scholar from Connecticut College claims that "the fact that her photos are labeled as 'art' and placed in galleries or museums instructs us to approach them with critical distance, to seek motive and hermeneutic depth within them".[233]

- Art exhibitions (solo)

In 2012, Johnnie Walker led the art exposition Arte urbana – Projeto Keep Walking Brazil in honor to Madonna, featuring artworks of 30 different graffiti artists.[234] The same year, a Colombian art exhibition was presented at EAFIT University curated by María Patricia García Mejía, showing the Madonnas of Javier Restrepo titled Como una oración (in English: Like a Prayer). According to María García this exhibition shows how the universality of Madonna also touched the plastic arts.[235]

A multidisciplinary exhibition, called Madonna: Ícono cultural-arte, moda y filatelia was presented at the Guayaquil Municipal Museum in 2013. The exhibition explored Madonna's impact and references in arts, fashion, philately and numismatics.[236] In 2017, Italian contemporary art exhibition Thank you Madonna – I miei sogni in technicolors was exhibited at Lea & Flò Palace curated by Michelangelo Prencipe.[237]

- Art exhibitions (secondary or part of the theme)

In 2004, Madonna had a special segment in the Alberto Gironella's retrospective Alberto Gironella. Barón de Betenebros, with the paintings Gironella devoted to her, and previously presented in 1994 as Más que pop, Madonna es la única surrealista.[238] In 2014, M- de Marilyn à Madonna was exhibited in Brazil curated by André Ferrari to commemorate the death of Marilyn Monroe and birth of Madonna, both events occurred in the month of August. It featured 46 artworks of different artists incorporating techniques of acrylic paints, collage and computer graphic images.[239]

Madonna was part of exhibition De Madonna a Madonna (in English: From Madonna to Madonna) installed in countries such as Chile (Centro Cultural Matucana 100), Spain (MUSAC) and Argentina (Juan B. Castagnino Fine Arts Museum) to approach the role of women throughout history.[240]

Sculptures and wax figures

| External image | |

|---|---|

Around 1988, in the town of Pacentro, Italy (the city of her paternal grandparents) some residents proposed putting up a 13-foot statue of a bustierwaring Madonna, hoping as much to attract tourists as to bestow honorary citizenship on its "most famous descendent", but the proposal was vetoed by the mayor and others.[241] The Italian sculptor Walter Pugni, who planned to erect the bronze statue, show off a 2-foot clay model of the statue to the press, and also justified Madonna as "a symbol for our children and represents a better world for them in the year 2000".[242] Brazilian plastic artist, Nico Rocha created in 1993, a 2.3-foot statue of Madonna to commemorate 10-years career of the singer and her first visit in Brazil.[243]

Several Madame Tussauds around the world have wax effigies of Madonna. Madame Tussauds Sydney, launched simultaneously three different Madonna's wax statues, making the first time they revealed that amount of one female performer in their history.[244] She is also depicted at the Musée Grévin of France among many others.[245]

-

National Wax Museum Plus (Irlanda)

-

National Wax Museum Plus (Irlanda)

-

Madame Tussauds London

See also

References

- ^ Bickford, Malina (September 9, 2013). ""It Was a Beautiful Thing:" Danceteria and the Birth of Madonna". Vice. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Aletti, Vince (December 12, 1999). "Ray of light: Madonna and her love affair with the lens". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cross 2007, p. 10

- ^ a b c d Gnojewski 2007, pp. 27–28

- ^ Stanton, Harry Dean (May 5, 2018). "Madonna talks to Harry Dean Stanton About Her Newfound Stardom". Interview. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ O'Brien 2007, p. 22

- ^ "Madonna 1979 Nudes To Be Featured at Brighton Festival". Popular Photography. April 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Gross, Michael (1985). "Madonna: Catholic Girl, Material Girl, Post-Liberation Woman". Official website of Michael Gross. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Walker 2003, pp. 65–89

- ^ a b "Madonna & Basquiat". ShowTime. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Madonna". Contemporary Art. Vol. 3. 1995. pp. 34–38. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Madonna". Contemporary Art. 3: 36. 1995. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Scaggs, Austin (October 29, 2009). "Madonna Looks Back: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Blaine, David (November 26, 2014). "Madonna". Interview. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Lipsky-Karasz, Elisa (May 2016). "The Art of Larry Gagosian's Empire" (PDF). Gagosian Gallery. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (April 7, 2017). "Glenn O'Brien, Writer and "TV Party" Host, Dead at 70". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Hoskyns, Barney (August 4, 2003). The Sound and the Fury: 40 Years of Classic Rock Journalism: A Rock's Backpages Reader. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-58234-282-5.

- ^ a b c Cascone, Sarah (July 12, 2019). "'Why Shouldn't I Be Able to Make Money Off This?': Madonna's Ex-Art Advisor on Why She's Selling the Singer's Intimate Personal Belongings". Artnet. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Glenn O'Brien – also starring Madonna, Basquiat, Viva and Warhol". Flux. November 26, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Gnojewski 2007, p. 14

- ^ a b Rolling Stone Press 1997, p. 156

- ^ Madonna (March 5, 1996). "Me, Jean-Michel, Love and Money". The Guardian. p. 32.

- ^ "Keith Haring: By John Gruen". Kirkus Reviews. May 20, 2010. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c Simone 2016, pp. 27–28

- ^ Caldwell, Caroline (September 5, 2012). "Vandalog interviewed COST – Part two – Vandalog – A Street Art Blog". Vandalog. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring Graffiti Jacket". Swann Galleries. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Bono, Sal (December 19, 2020). "The Case of Michael Stewart, the New York Artist Some Say Was Sentenced to Death for Drawing on Subway Tile". Inside Edition. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Eckardt, Stephanie (August 16, 2018). "Madonna Is Secretly an Art World Influencer". W. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Peterkin, Tom (April 11, 2002). "Artist reveals the 'good and bad' Madonna". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Aletti, Vince; Schonauer, David (March–April 2000). "Q&A Madonna the real views of a modern muse. On art and reality". American Photo. 11 (2): 44–48, 55. ISSN 1046-8986. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Faith & Wasserlein 1997, p. 119

- ^ "Girl gone wild: is it time for Madonna to grow up?". The Irish Times. March 23, 2012. Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Harrison 2017, pp. 68–69

- ^ a b Bayles 1996, p. 334

- ^ Flynn 2017, p. online

- ^ a b c May 1997, p. 169

- ^ Hoesterey 2001, p. 114

- ^ a b Burt 1994, p. 217

- ^ Versace, Donatella (November 28, 2019). "Madonna Has Always Been a Fighter". L'Officiel. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (May 15, 1991). "Cover Story: It's Not". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ Aletti, Vince (December 12, 2009). "Ray of light: Madonna and her love affair with the lens". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 4, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Morton 2001, p. 15

- ^ a b Rißler-Pipka, Lommel & Cempel 2015, p. 225

- ^ a b Sexton 2007, p. 34

- ^ Merry, Stephanie (June 17, 2015). "Remember when Madonna used to push boundaries? Her new video proves those days are long gone". Washington Post. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Who Does Madonna Collect? See Artists in the Material Girl's Private Collection". Artspace. September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ Aletti, Vince (March–April 2000). "Q&A Madonna the real views of a modern muse". American Photo. 11 (2): 44–48. ISSN 1046-8986. Archived from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "The many influences that made Madonna the Queen of Pop". Decades. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Richwine, Lisa; Choy, Marguerita (September 15, 2020). "Madonna to direct and co-write a movie about her life and music". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Guilbert 2015, p. 68

- ^ Gilbert & Gubar 2021, p. online

- ^ Ward 2010, p. online

- ^ Munro, Cait (July 23, 2015). "Madonna Is the Latest Celebrity to Compare Herself to Pablo Picasso". Artnet. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Kim Taylor (March 13, 2015). "Bitch, I'm Madonna: I Want to Live Forever, and I'm Going to". Vice. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Bego 1992, p. 80

- ^ O'Brien 2007, p. 284

- ^ a b "Mr. Brainwash" (PDF). Wanrooij Gallery. October 17, 2017. pp. 4, 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 19, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- "Mr. Brainwash: Portraits of Musicians". Artsy. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- Brainwash, Mr. (September 9, 2009). "Madonna's "Celebration" Album". Official Website of Mr. Brainwash. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "Madonna mostra o resultado do grafite de Kobra no hospital Mercy James". Caras (in Portuguese). October 7, 2017. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ "Brazilian graffiti artist illustrates Madonna's new single". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese and English). April 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lord, Alfred (August 16, 2018). "Aldo Díaz, el fan brasilero que conquistó con arte a Madonna" (in Spanish). Shock. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- Kreps, Daniel (May 12, 2017). "Madonna Announces 'Rebel Heart Tour' Concert Film/Live Album Date". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "25 Art World Women at the Top, From Sheikha Al-Mayassa to Yoko Ono". Artnet. April 17, 2014. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ a b O'Brien 2007, p. 391

- ^ Seelinger, Lani (October 12, 2016). "7 Astounding Celebrity Art Collections". The Culture Trip. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Capps, Kriston (October 4, 2013). "The Artist Is Ever Present". New York. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Embuscado, Rain (August 26, 2016). "Madonna Surprises Fans With Impromptu MoMA Visit". Artnet. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Walker 1993, p. 188

- ^ Dumenco, Simon (May 7, 2004). "Fashion photographer seeks models/celebrities for a little rough play". New York. Archived from the original on November 30, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Millard, Rosie (October 2, 2001). "Madonna: Turner's perfect choice". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Akbar, Arifa (October 3, 2001). "Art-lover Madonna agrees to present this year's Turner Prize". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Harris 2003, p. 205

- ^ Leese 2006, p. 191

- ^ Louaguef, Sarah (November 6, 2014). "Madonna fait son show au MoMA". Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on March 5, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Brooklyn Talks: Madonna X Marilyn Minter SOLD OUT". Brooklyn Museum. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenberger, Alex (November 7, 2013). "Why Does Madonna Want to Make "Art for Freedom?"". Artspace. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Bright & Aletti 2007, p. online

- ^ "Inmaterial Whirl". Ad Age. April 1, 2003. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Robinson, Walter (April 14, 2003). "Weekend Update". Artnet. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (September 17, 2013). "Madonna's Secret Project Revealed: Pop Superstar to Release Short Film Via BitTorrent to Aid Global 'Artistic Expression'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 20, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Robertson 2014, p. 82

- ^ Escalante-de Mattei, Shanti (May 10, 2022). "Beeple and Pop Icon Madonna Band Together to Make New NFT Project". ARTnews. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (May 10, 2022). "Madonna Preps NSFW 'Mother of Creation' NFT Collection". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Rakewell (May 15, 2022). "Immaterial girl – Madonna enters the metaverse". Apollo. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c Irwin, Michael (May 12, 2022). "'A Matryoshka Doll of Nightmares' — Art World Reacts to Beeple x Madonna NFT". Ocula. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Waite, Thom (May 12, 2022). "What's the story behind Madonna's nude NFTs?". Dazed. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Rory (May 23, 2022). "Madonna's Provocative NFT Collection Generates 300 ETH at Auction". NFT Plazas. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Fhlathúin 1998, p. 206

- ^ Larson, Kay (November 9, 1992). "Wild Child". New York: 74–75. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ D'Arcy, David (October 31, 1992). "Whitney compares Basquiat to Leonardo da Vinci in new retrospective". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Outwater, Myra Y. (November 12, 1995). "Modotti Photos Capture Mexican Life". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Ibsen 1997, p. 57

- ^ "Madonna Sponsors Show". The Guardian. February 17, 1996. p. 5.

- ^ "The complete Untitle Film Stills Cindy Sherman". Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). September 26, 1997. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Guilbert 2015, p. 76

- ^ Cody & Cheng 2015, p. online

- ^ a b c d "Madonna to present Turner prize". BBC. October 2, 2001. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Madonna lends painting by Frida Kahlo to Tate Modern". Tate. October 4, 2001. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Leitch, Luke (April 12, 2012). "Madonna shows us her collection". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ciccone 2008, pp. 150–153

- ^ a b c Holmes, Randy (November 1, 2013). "Elton John, Madonna Among Entertainment Industry's "Top 25 Art Collectors"". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 5, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- Miller, Mark; Pener, Degen; Pyun, Jeanie (October 31, 2013). "The Hollywood Reporter Reveals the Industry's Top 25 Art Collectors". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "Take a Look Inside Madonna's $100 Million Blue-Chip Art Collection". Artnet. March 17, 2015. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ Aletti, Vince (December 12, 1999). "Ray of light: Madonna and her love affair with the lens". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 4, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (March 12, 2015). "Madonna on 'Howard Stern': 10 Things We Learned". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Madonna on Instagram: "Visiting My Past which is never gone…………………#jmb #research 🎥🎬🎞🖤"". Instagram. July 22, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Hopkinson, Amanda (January 5, 1997). "In Brief". The Independent. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Rolling Stone Press 1997, p. 215

- ^ "Untitled". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "The Six Second Epic". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Madonna to present Turner Prize". The Guardian. October 3, 2001. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b García Canclini 1991, p. 304

- ^ Ciccone 2008, p. 120

- ^ "Show Us Your Basquiat!". Official Website of Madonna. July 24, 2015. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ ""Iconic", tutti i volti di Madonna: la regina del pop vista dagli artisti". la Repubblica (in Italian). November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Madonna, che passione!". Exibart (in Italian). November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Ioannou, Theo (October 20, 2017). "Madonna Posts Greek Graffiti of Herself on her Instagram Account". Greek Reporter. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Angers, Jean Philippe; The Canadian Press (November 23, 2018). "Madonna buys work from Montreal 'vandal' artist, shows it off on Instagram". National Post. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Khomami, Nadia (January 4, 2022). "Talents of Madonna's son divide critics after he is revealed as secret artist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Barbeta, Amparo (August 9, 2019). "Arrúe, el valenciano que ha conquistado a Madonna". Levante-EMV (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- Lozano, María (March 3, 2022). "Jesús Arrúe, el pintor español que Madonna ha utilizado contra Putin: "Mis armas son los pinceles"". ABC (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Duffy, Judith (January 21, 2017). "Scottish artist whose Trump painting was shared by Madonna unveils new portrait". The Herald. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- McKenzie, Steven (January 18, 2017). "Madonna shares Scottish artist's Donald Trump painting". BBC. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- Elbaor, Caroline (January 19, 2017). "Madonna's Post of Scottish Artist's Trump Artwork Goes Viral". Artnet. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Spin Patrol". Spin. Vol. 7, no. 9. December 1991. p. 29. Retrieved November 22, 2022.

- ^ Andrews, Farah (August 19, 2020). "Madonna hosts family art sale to raise money for Lebanese charity following Beirut explosion". The National. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "Madonna sells Leger painting for $7.2m". BBC. May 8, 2013. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Reuters Staff (April 3, 2013). "Madonna sells abstract painting to fund girls' education". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Hollywood.com Staff (April 21, 2014). "How Madonna is Changing the World with Art For Freedom". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Batty, David (December 2, 2016). "Madonna's art collection and more on sale at starry benefit". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.