Stefan Nemanja

| Stefan Nemanja | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

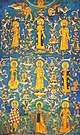

The fresco of Saint Simeon (Stefan Nemanja), King's Church in Studenica monastery | |||||

| Grand Prince of Serbia | |||||

| Reign | 1166–1196 | ||||

| Coronation | 1166 | ||||

| Predecessor | Stefan Tihomir | ||||

| Successor | Stefan II Nemanjić | ||||

| Born | 1113/4 Ribnica | ||||

| Died | February 13, 1199 Monastery of Hilandar | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Anastasia of Serbia | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nemanjić | ||||

| Father | Zavida | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Stefan Nemanja (Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [stêfaːn ně̞maɲa]; ca 1113 – 13 February 1199) was the Grand Prince (Veliki Župan) of the Serbian Grand Principality (also known as Rascia) from 1166 to 1196. A member of the Vukanović dynasty, Nemanja founded the Nemanjić dynasty, and is remembered for his contributions to Serbian culture and history, founding what would evolve into the Serbian Empire, as well as the national church. According to the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Nemanja is also among the most remarkable Serbs for his literary contributions and altruistic attributes.[1]

In 1196, after three decades of warfare and negotiations which consolidated Serbia while distinguishing it from both Western and Byzantine spheres of influence, Nemanja abdicated in favour of his middle son Stefan Nemanjić, who became the first King of Serbia. Nemanja ultimately went to Mount Athos, where he became a monk and took the name of Symeon, joining his youngest son (later known as Saint Sava), who had already become the first archbishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Together with his son Sava, Nemanja had built the Serbian Hilandar Monastery at Mount Athos from 1198-1199, and issued the "Hilandar Charter". The monastery later became the cradle of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Serbian Orthodox Church canonized Stefan Nemanja shortly after his death under the name Saint Symeon the Myrrh-streaming (Свети Симеон Мироточиви) after numerous miracles.

Early life

Nemanja was born around the year 1113 AD in Ribnica, Zeta (in the vicinity of present-day Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro). He was the youngest son of Zavida, a Prince of Zahumlje, who after a conflict with his brothers was sent to Ribnica where he had the title of Lord. Zavida (Beli Uroš) was most probably a son of Uroš I or Vukan. Since western Zeta was under Roman Catholic jurisdiction, Nemanja received a Latin baptism,[2] although much of his later life was spent balancing Western and Eastern forms of Christianity.

After Byzantine armies defeated Nemanja's kinsmen Đorđe of Duklja and Desa Urošević, leading to the decline of that branch of the Vojislavljević family, Zavida took his family to their hereditary lands at Rascia. Upon arriving in Ras, the capital of Rascia, Nemanja was re-baptised in the Eastern Orthodox Church, in the Church of St. Apostles Peter and Paul which was an episcopal see.

Prince

Upon reaching adulthood, Nemanja became "Prince (Župan) of Ibar, Toplica, Rasina and Reke", receiving the česti (parts of the state) from the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I. Manuel had appointed Zavida's eldest son Tihomir as the supreme Grand Prince of the Serb lands; his brother Stracimir ruled West Morava, Miroslav ruled Zahumlje and Travunia.[3]

In 1163, Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos installed Nemanja's older brother Tihomir as Grand Župan of Rascia in Desa's place, which disappointed Nemanja greatly, as he expected that he would get the throne. Nemanja met Emperor Manuel in Niš in 1162, who gave him the region of Dubočica to rule over and declared him independent. The Emperor gave him a Byzantine court title as it was important for the Emperor to have the borderlands of the Empire ruled by loyal leaders. Nemanja's Serb squadrons fought in the Imperial Army in 1164 in Srem during the wars against the Kingdom of Hungary. Nemanja ruled independently; he built the Monastery of Saint Nicholas in Kuršumlija and the Monastery of the Holy Mother of Christ near Kosanica-Toplica, without the Tihomir's approval. His brothers invited him to a council at Ras, supposedly to resolve the situation, but instead they imprisoned him in a nearby cave. Nemanja's supporters advised church leaders that Tihomir had done this because he disapproved of church building, something that would later help Nemanja greatly.[4] A later legend claimed Saint George himself freed Nemanja from the cave.[5]

Between 1166 and 1168, Prince Nemanja rebelled against his older brother Tihomir, and deposed him and his brothers, Miroslav and Stracimir. The Byzantine Emperor raised a mercenary army for Tihomir, made up of Greeks, Francs and Turks, which Nemanja defeated at the Battle of Pantino, south of Zvečan. Tihomir drowned in the Sitnica river, and the other brothers surrendered to Nemanja, who allowed them to rule their previous lands.[3] Nemanja assumed the title of Grand Župan of all Serbia , and took the first name Stefan (from Greek Stephanos meaning "crowned").

Nemanja married a Serbian noblewoman, Ana, with whom he had three sons: Vukan, Stefan and Rastko.

Grand Prince

Stefan Nemanja built the church of Đurđevi Stupovi (Pillars of St. George) in Ras in 1171. According to the legend, this was to thank Saint George for freeing him from the cave in which his brothers had imprisoned him, as well as helping him rise to power. The same year, Nemanja had his third son - Rastko.

In 1171, Grand Župan Stefan Nemanja sided with the Venetian Republic in a dispute with the Byzantine Empire, with the aim of gaining full independence from Byzantine rule. The Venetians incited the Slavs of the eastern Adriatic littoral to rebel against Byzantine rule. Nemanja joined them, launching an offensive towards the coastal city of Kotor. A German fleet also formed to replace the Venetian navy, and advanced eastwards in the September 1171, capturing Ragusa. Nemanja also made an alliance with the Kingdom of Hungary, and, though the Hungarians, with the Duchy of Austria. Grand Prince Nemanja then dispatched troops to the Morava valley in 1172, to disrupt communications and commerce between Niš and Belgrade and instigate a rebellion amongst the local Serbs at Ravno. However, Ravno's Serbs refused to allow passage to the King of Saxony Heinrich the Lion. The Serbs organised a surprise attack on the German camp, then attacked their own neighbours.

However, in 1172, the anti-Byzantine coalition that Nemanja had joined with the Kingdom of Hungary, the Venetian Republic and the Holy Roman Empire collapsed. Venice faced a mutiny and an outbreak of plague that devastated her navy, while the King of Hungary died and a new, pro-Byzantine King ascended that throne. Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos had launched an expedition and Nemanja's defeat seemed certain. Thus, the Grand Župan sought leave to parley and met the Emperor in Niš with his head and feet bare and a halter around his neck, much as the rebel Reginald of Chatillon who had established himself as Prince of Antioch had 13 years before, and received reinstatement. However, although Nemanja bowed before Emperor Manuel and surrendered his personal sword, he was imprisoned and brought to the Imperial Capital of Constantinople to take part in a triumphal entry as a defeated barbarian.[6] However, the emperor also befriended Nemanja and saw that he was tutored. Nemanja vowed to never again attack Manuel, while the Emperor in return recognized Stefan Nemanja and his bloodline as the rightful Grand Župans of the Rascian lands.

Stefan Nemanja forced his brothers, Stracimir of West Moravia and Miroslav of Zachlumia and Lim to accept his supreme rule in return for his forgiveness; he also made Tihomir's son Stefan Prvoslav surrender his claim to the throne. His army was involved only in a single conflict at the request of his Byzantine overlord, in Asia Minor. Nemanja also used the following decade to deal with the Bogomil heresy that had spread to his realm, as well as to neighboring Bosnia, from neighboring Bulgaria, and strengthening Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Grand Župans burned their books and confiscated their lands, as well as burned some at the stake,[citation needed] and exiled others. Most of the exiled Bogumils from his realm found refuge in Bosnia, under protection of its ruler Kulin Ban. By the end of his reign, Stefan Nemanja had completely rooted out the Bogomils. Moreover, Prince Stracimir built the Monastery of the Mother of Christ in his capital at Moravian Grac (today Čačak), while Prince Miroslav constructed the Monastery of Saint Peter on Lim. Miroslav also married the sister of Kulin Ban, creating a bloodline link between two ruling dynasties.

Death of the Emperor

Following Emperor Manuel I Komnenos' death in 1180, Stefan Nemanja no longer believed he owed any allegiance to the Byzantines, characterizing his vows as being to the Emperor, not the Empire. He took advantage of the Empire's weakened state, and allowed his brothers leeway as well. Prince Miroslav protected the Narentine Kačić family, pirates that had robbed and murdered Rainer (Arnerius), the archbishop of Split. Although the pope demanded the prince execute the perpetrators and surrender the loot, Miroslav refused, and instead expelled the Bishop of Ston. Excommunicated by the Papacy, Miroslav merely replaced the vacant church buildings in the vicinity of Ston.[5]

In 1183, Stefan Nemanja formed a new alliance, with King Bela III of Hungary, and invaded Byzantine soil. Andronicus Comnenus had taken over the imperial throne, but was not recognized. The Massacre of the Latins in Constantinople inflamed the tense political situation. Kulin Ban of Bosnia also joined Nemanja. The Byzantine forces in the eastern Serb borderlands were led by Alexios Branas and Andronikos Lapardas. Inner fights occurred, as Branas supported the new Emperor and Lapardas, opposing, deserted with his troops. The Hungarian-Serbian military soon pushed the Byzantines out of the Morava Valley and advanced all the way to Sofia, raiding Belgrade, Braničevo, Ravno, Niš en route. However, the Hungarians soon withdrew, leaving Nemanja's forces raiding across western Bulgaria.

In 1184, Prince Miroslav tried to retake the islands of Korčula and Vis, but on 18 August 1184, his fleet was devastated by the Ragusan navy at Poljice near Koločep, so Miroslav signed a peace treaty with the Republic of Ragusa. However, his brother, Prince Stracimir, did not feel bound by that defeat and the following year raided Korčula and Vis with the Doclean fleet. However, by time he marshalled his forces, he decided to join in Miroslav's peace efforts because the Byzantines launched a counter-attack on Serbia. Nonetheless, a Bulgarian uprising in the Danubian areas sidetracked the imperial offensive, so Stefan Nemanja took advantage of the complex situation and conquered the Timok Frontier with Niš and sacked Svrljig, Ravno and Koželj. While Nemanja held Niš, it served as his capital and base of operations.

Third Crusade

In 1188 Stefan Nemanja sent an envoy to Frederick Barbarossa, inviting him to stay in Serbia during his Crusade to the Holy Land. Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, disembarked on the Third Crusade and arrived on 27 July 1189 at Niš with 100,000 Crusaders, hosted by Stefan Nemanja and Stracimir. A marriage was arranged between the daughter of Berthold, Duke of Merania and Miroslav's son Toljen to strengthen Serbian-German relations. Nemanja proposed that Barbarossa join him and the Venetians and strike at the Byzantines, but Barbarossa remained intent on his Crusade.[7] Barbarossa recognized that he needed Byzantine help to transport his forces to Asia, but his plans changed when a Byzantine force stopped him from reaching his next stop at Sophia. The Byzantines also started raiding Barbarossa's army, which infuriated Barbarossa so much that he planned an offensive to Constantinople itself. Stefan Nemanja offered 20,000 men to support Barbarossa's military campaign, and the Bulgarians offered more than twice that number. Despite being in his early 70s, Stefan Nemanja followed the Crusader Army to the border at the Gate of Trajan. He then dispatched envoys to Adrianople to finalize this Western alliance. While Nemanja's envoys were negotiating with Berthold as Barbarossa's representative, Nemanja took Pernik, Zemen, Velbužd, Žitomisk, Stobi, Prizren and rest of Kosovo and Metohija and even Skopje. However, Barbarossa never consummated an alliance with Nemanja, instead signing a peace treaty with Byzantine representatives on 14 February 1190 in Adrianople.

Conflict with Byzantines and successions

In 1190, the new Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos prepared a massive and experienced army to strike against Nemanja. The same year, Nemanja finished his magnificent Virgin's Church in the Studenica monastery out of white marble which later became the Nemanjić dynasty's hallmark. Also in 1190 his brother Miroslav died of old age, so Stefan Nemanja temporarily assigned his pious youngest son Rastko as the new Prince of Zahumlje in Ston.

In fall of 1191, the well-prepared Byzantine army, led by the Emperor himself, crushed Nemanja's forces in South Morava. Stefan Nemanja retreated into the mountains, as Byzantines raided all along the river and even burned down the capital in Kuršumlija. However, Nemanja began raiding the Byzantine armies, so Emperor Isaac decided to negotiate a final peace treaty. Stefan Nemanja relinquished a large part of his conquests, east of the river of Great Morava, and recognized Byzantine supremacy, while in return the Emperor recognized him as the rightful Grand Prince. Nemanja's son Stefan married the Byzantine princess Eudokia Angelina and received the title of sebastokrator, among the highest Byzantine court titles only given to Imperial family members. To separate the Serbs from the Bulgarians, the Emperor kept Niš and Ravno; while recognizing Stefan Nemanja's rule over the lands of Zeta, what is today Kosovo, and Pilot previously held by Arbanon.

In 1192 Nemanja's youngest son Rastko retired to Mount Athos where he accepted monastic vows and took the name Sava. This greatly saddened Nemanja. In Rastko's place, Miroslav's son Toljen became Prince of Zahumlje and founded a local dynasty. Serbia seemed once again endangered once as Nemanja's former ally, King Bela of Hungary invaded from the north. However, Nemanja's forces quickly pushed the Hungarians back across the border in 1193.

In 1195, Stefan Nemanja's brother-in-law Alexios III Angelos inherited the Byzantine throne. Nemanja, tired of ruling, expanded the power and lands of his eldest son Vukan. He joined Zeta with Trebinje (Travunija), Hvosno (Metohija) and his capital of Toplica under Vukan's absolute rule.

Abdication and monastic life

On March 25, 1196, Stefan Nemanja summoned a Council in Ras, where he officially abdicated in favour of his second son, Stefan, to whom he bequeathed all his earthly possessions. Although Vukan was Nemanja's eldest son, Nemanja preferred to see Stefan II on the Serbian throne in part because Stefan had married the Byzantine princess Eudokia. However, traditions of primogeniture, would instead mean Vukan, his first son, should inherit the throne. Vukan reacted on this change in succession by declaring himself King of Duklja.

Nemanja took monastic vows with his wife Ana in Ras' Church of Saint Peter and Paul. He took the monastic name of Simeon; his wife became Anastasia. Simeon subsequently retired to his Studenica monastery, and Anastasia retired to the Monastery of the Mother of Christ in Kuršumlija. However, after about 18 months, Simeon journeyed to Mount Athos, and joined his son Sava (formerly Rastko) in the Vatopedi monastery. In 1199, the two rebuilt together the ruined Eastern Orthodox Monastery of Hilandar which the Byzantine Emperor had given to the Serbian people and which became the heart of Serbian spiritity.

Death and Legacy

Stefan Nemanja | |

|---|---|

Sts. Sava and Simeon | |

| Saint, Venerable | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 1200 by Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Feast | 26 February [O.S. 13 February] |

Knowing his death was near in his 86th year, Simeon asked to be placed on a mat in front of the icon of the Virgin Hodegetria with a stone for his pillow. He died in front of his son Sava and other monks, on 13 February 1200.[8] He was buried in the grounds of Hilandar monastery. His last words requested that Sava take his remains to Serbia, "when God permits it, after a certain period of time". Sava later wrote the Liturgy of Saint Simeon in Nemanja's honour.

In 1206 Sava brought his father's remains to Rascia, where his brothers were fighting a civil war and tearing apart the Serb lands their father had so painfully reunited. The two brothers made peace and returned to their demesnes. Simeon was re-buried in 1207 in his personal foundation, the Studenica monastery, where holy oil again seeped, from his new grave. According to legend, holy oil (myrrh) seeped from Nemanja's tomb, thus his epithet the Myrrh-streaming. However, the miracle has not recurred in 300 years. Nonetheless, his remains are, even in modern times, reputed to emit "a sweet smell, like violets".[9] Because of this and numerous miracles, the Serbian Orthodox Church canonised him in 1200, and declared his feast-day on 26 February [O.S. 13 February]. The cult of St. Simeon helped consolidate Serb national identity, and still lives on in Studenica and among the monks of Mount Athos, who cherish his life and works as well as remains.

Name and title

Various names have been used to refer to Stefan Nemanja, including Stefan I and the Latin Stephanus Nemania. Sometimes the spelling of his name is anglicised, to become Stephen Nemanya. In the latter part of his life, he became a monk and hence was referred to as Monk Simeon or Monk Symeon. After his death, he was canonised by the Orthodox Church, and became St. Symeon the Myrrh-streaming. His son and successor, Stefan the First-Crowned, called him The Gatherer of the Lost Pieces of the Land of his Grandfathers, and also their Rebuilder. His other son Sava, called him Our Lord and Autocrat, and ruler of the whole Serbian land.[10]

Family

Nemanja was married to a Serb noblewoman by the name of Ana. They had three sons and three daughters:

- Vukan Nemanjić - Prince of Doclea and briefly Grand Prince of Rascia.

- Stefan Nemanjić - Nemanja's successor, first King of All Serbian lands, 1196–1228

- Rastko Nemanjić (Saint Sava) (1171–1236) - The first archbishop and saint of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Jefimija - married Manuel Komnenos Doukas Regent of Thesaloniki (+1241).[11][12]

- Unnamed daughter - married Bulgarian nobleman Tihomir Asen, mother of Bulgarian emperor Konstantin Tih (r. 1257–77).

- possibly Elena-Evgenia, wife of Ivan Asen I

And possibly:

Foundations

Stefan Nemanja founded, restored and reconstructed several monasteries. He also established the Rascian architectural style, that spanned from 1170-1300.

- Monastery of Saint Nicholas, in Kuršumlija

- Monastery of Saint Mother of Christ, between Kosanica and Toplica

- Monastery Temple of George's Columns (Đurđevi Stupovi), in 1171 in Ras

- Monastery Temple of the Immaculate Holy Virgin the Benefactor (Studenica), in 1190 in Ibar

- Church of Saint Mother of Christ, at the confluence of the Bistrica and the Lim

- Monastery of Saint Nicholas, in Kaznovići/Končulj on the Ibar

- Nunnery of Mother of Christ, in Ras

Reconstructions

- Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos, in 1199

- Monastery of Saint Archangel Michael, in Skopje

- Monastery of Saint Pantheleimon, in Niš

Donations

- Church of Lord, Holy Grave and Christ's Arrisal, in Jerusalem

- Church of Saint John the Forerunner, in Jerusalem

- Church of Saint Theodosios, in the Desert of Bethlehem

- Church Saint Apostole Peter and Paul, in Rome

- Church of Saint Nicholas, in Bari

- Monastery/Church of the Virgin of Evergethide, in Constantinople

- Monastery/Church of Saint Demetrios, in Thessalonika

See also

- History of Serbia; List of Serbian monarchs

- History of Montenegro; List of rulers of Montenegro

- History of Herzegovina

Annotations

- Name: Stefan Nemanja (Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [stêfaːn ně̞maɲa] ; Old Church Slavonic: Стѣфань Неманя.

References

- ^ 100 najznamenitijih Srba. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 1993. ISBN 86-82273-08-X.; 1st place

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 3

- ^ a b Judah 1997, p. 31

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 4

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 20

- ^ Obolensky, Six Byzantine Portraits(Oxford: Clarenden Press), p. 116

- ^ Obolensky, p. 119.

- ^ Obolensky pp. 126-7

- ^ Kindersley, 23

- ^ Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 390

- ^ Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy of the Nemanjić". Genealogy.EU.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/SERBIA.htm#Efimijadied12181225

Sources

- John V.A. Fine. (1991). The early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the 6th to the Late 12th Century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7

- John V.A. Fine. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4

- Judah, Tim (1997). The Serbs: History, Myth & the Destruction of Yugoslavia, Yale University Press.

- Kindersley, Anne (1976). The Mountains of Serbia: Travels through Inland Yugoslavia, John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.

- Mandic, O. Dominic (1970). Croats and Serbs: Two old and different Nations. Translated by Vicko Rendic and Jacques Perret. Available at: www.magma.ca/~rendic.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: the History behind the Name, Hurst & Company.

- The Serbian Unity Congress.

- Servia/Serbia, Catholic Encyclopedia (1907)

- Veselinović, Andrija & Ljušić, Radoš (2001). Српске династије, Platoneum.

- CD Chilandar by Studio A, Aetos, Library of Serb Patriarchate and Chilandar monastery, Belgrade, 1998

- Ćorović, Vladimir, Istorija srpskog naroda, Book I, (In Serbian) Electric Book, Rastko Electronic Book, Antikvarneknjige (Cyrillic)

- Treci Period, I, Stevan Nemanja

Further reading

- Stanković, V. D. (2015). "Construction of the feudal state at the time of Stefan Nemanja". Baština (38): 45–55.

- Andrejić, Ž. (2010) O poreklu velikog župana Stefana Nemanje. Bratstvo, Beograd, (14): 23-67

- Foretić, V. (1951) Ugovor Dubrovnika sa srpskim velikim županom Stefanom Nemanjom i stara dubrovačka djedina. Rad JAZU, 283, 52-53

- Zarković, B. (2007) O južnim granicama Srbije u vreme vladavine Stefana Nemanje. Baština, =sv. 23

- Barišić, F. (1971) Hronološki problemi oko godine Nemanjine smrti. Hilandarski zbornik, 2

External links

- Serbian Unity Congress - Rulers of the Land

- Template:MLCC

- Template:Sr icon History of the Serbs - Third Period - Stephen Nemanya, by Vladimir Ćorović

- Template:Sr icon The Holy bloodline of Stefan Nemanja by Željko Fajfrić

- Template:Sr icon The Holy bloodline of the Nemanjics - Stephen Nemanya

- Template:Sr icon The Nemanjics - Stephen Nemanya

- 1113 births

- 1199 deaths

- 12th-century Serbian monarchs

- 12th-century Christian saints

- 12th-century rulers in Europe

- Orthodox monarchs

- Monarchs who abdicated

- Serbian saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Medieval Serbian Orthodox clergy

- Burials in Serbia

- Byzantine people of Slavic descent

- Ktetors

- Founders of Christian monasteries

- Burials at Serbian Orthodox monasteries

- 12th-century Eastern Orthodox Christians

- Eastern Orthodox royal saints