Indigenous Australians: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 58.165.91.221 (talk) to last revision by Jusdafax (HG) |

Ohconfucius (talk | contribs) m per WP:MOSNUM, WP:Linking, WP:ENGVAR |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|image= [[Image:AlbertNamatjira-1949-AliceSprings.jpg|70px|Albert Namatjira]], [[File:Douglas nicholls.jpg|70px|Sir Douglas Nicholls]], [[File:Oodgeroo Noonuccal 1975.jpg|70px]], [[Image:Ernie Dingo.jpg|70px|Ernie Dingo]], [[Image:David Gulpilil.jpg|70px|David Gulpilil]], [[File:Jessica Mauboy at the 2009 ARIA awards.jpg|70px|Jessica Mauboy]], [[Image:David wirrpanda.jpg|70px|David Wirrpanda]], [[Image:Cathy Freeman 2000 olympics.jpg|70px|Cathy Freeman]], [[File:Christine Anu.jpg|50px|Christine Anu]] |

|image= [[Image:AlbertNamatjira-1949-AliceSprings.jpg|70px|Albert Namatjira]], [[File:Douglas nicholls.jpg|70px|Sir Douglas Nicholls]], [[File:Oodgeroo Noonuccal 1975.jpg|70px]], [[Image:Ernie Dingo.jpg|70px|Ernie Dingo]], [[Image:David Gulpilil.jpg|70px|David Gulpilil]], [[File:Jessica Mauboy at the 2009 ARIA awards.jpg|70px|Jessica Mauboy]], [[Image:David wirrpanda.jpg|70px|David Wirrpanda]], [[Image:Cathy Freeman 2000 olympics.jpg|70px|Cathy Freeman]], [[File:Christine Anu.jpg|50px|Christine Anu]] |

||

|caption = [[Albert Namatjira]], [[Douglas Nicholls]], [[Oodgeroo Noonuccal]], [[Ernie Dingo]], [[David Gulpilil]], [[Jessica Mauboy]], [[David Wirrpanda]], [[Cathy Freeman]], [[Christine Anu]] |

|caption = [[Albert Namatjira]], [[Douglas Nicholls]], [[Oodgeroo Noonuccal]], [[Ernie Dingo]], [[David Gulpilil]], [[Jessica Mauboy]], [[David Wirrpanda]], [[Cathy Freeman]], [[Christine Anu]] |

||

|flag = [[Image:Australian Aboriginal Flag.svg|80px]][[Image:Torres Strait Islanders Flag.svg|79px]] |

|flag = [[Image:Australian Aboriginal Flag.svg|80px]] [[Image:Torres Strait Islanders Flag.svg|79px]] |

||

|population = 550,000 (2001 data projected to 2010)<ref>[http://epress.anu.edu.au/agenda/011/02/11-2-NA-1.pdf ANU.edu.au] [[Australian National University]]</ref><br />2.7% of Australia's population |

|population = 550,000 (2001 data projected to 2010)<ref>[http://epress.anu.edu.au/agenda/011/02/11-2-NA-1.pdf ANU.edu.au] [[Australian National University]]</ref><br />2.7% of Australia's population |

||

|region1 = [[New South Wales]] |

|region1 = [[New South Wales]] |

||

|pop1 = 148,200 |

|pop1 = 148,200 |

||

|ref1 = |

|ref1 = |

||

|region2 = |

|region2 = Queensland |

||

|pop2 = 146,400 |

|pop2 = 146,400 |

||

|ref2 = |

|ref2 = |

||

|region3 = |

|region3 = Western Australia |

||

|pop3 = 77,900 |

|pop3 = 77,900 |

||

|ref3 = |

|ref3 = |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

|pop8 = 4,000 |

|pop8 = 4,000 |

||

|ref8 = |

|ref8 = |

||

|rels= Majority |

|rels= Majority Christianity, with minority following traditional [[animist]] ([[Dreamtime]]) beliefs |

||

|langs=Several hundred [[Indigenous Australian languages]] (many extinct or nearly so), [[Australian English]], [[Australian Aboriginal English]], [[Torres Strait Creole]], [[Australian Kriol language|Kriol]] |

|langs=Several hundred [[Indigenous Australian languages]] (many extinct or nearly so), [[Australian English]], [[Australian Aboriginal English]], [[Torres Strait Creole]], [[Australian Kriol language|Kriol]] |

||

|related= ''see'' [[List of Indigenous Australian group names]] |

|related= ''see'' [[List of Indigenous Australian group names]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Indigenous Australians''' are the original inhabitants of the |

'''Indigenous Australians''' are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands and the descendants of these peoples.<ref>Tim Flannery (1994), The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People, ISBN 0-8021-3943-4 ISBN 0-7301-0422-2</ref> Indigenous Australians are distinguished as either [[Australian Aborigines|Aboriginal people]] or [[Torres Strait Islanders]], who currently together make up about 2.7% of Australia's population. |

||

The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous to the [[Torres Strait]] Islands, which are at the northern-most tip of |

The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous to the [[Torres Strait]] Islands, which are at the northern-most tip of Queensland near [[Papua New Guinea]]. The term "Aboriginal" has traditionally been applied to indigenous inhabitants of mainland Australia, [[Tasmania]], and some of the other [[List of islands of Australia|adjacent islands]]. |

||

The earliest definite human remains found to date are that of [[Mungo Man]], which have been dated at about 40,000 years old, but the time of arrival of the ancestors of Indigenous Australians is a matter of debate among researchers, with estimates ranging as high as 125,000 years ago.<ref name="uow2004">[http://media.uow.edu.au/news/2004/0917a/index.html "When did Australia's earliest inhabitants arrive?"], ''University of Wollongong'', 2004. Retrieved |

The earliest definite human remains found to date are that of [[Mungo Man]], which have been dated at about 40,000 years old, but the time of arrival of the ancestors of Indigenous Australians is a matter of debate among researchers, with estimates ranging as high as 125,000 years ago.<ref name="uow2004">[http://media.uow.edu.au/news/2004/0917a/index.html "When did Australia's earliest inhabitants arrive?"], ''University of Wollongong'', 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2008.</ref> |

||

There is great diversity among different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own unique mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities.<ref>[http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/3.2/Hodge.html "Aboriginal truth and white media: Eric Michaels meets the spirit of Aboriginalism"], ''The Australian Journal of Media & Culture'', vol. 3 no 3, 1990. Retrieved |

There is great diversity among different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own unique mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities.<ref>[http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/3.2/Hodge.html "Aboriginal truth and white media: Eric Michaels meets the spirit of Aboriginalism"], ''The Australian Journal of Media & Culture'', vol. 3 no 3, 1990. Retrieved 6 June 2008.</ref> |

||

Although there were over 250-300 spoken languages with 600 dialects at the start of European settlement, fewer than 200 of these remain in use<ref>[http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.NSF/2f762f95845417aeca25706c00834efa/aadb12e0bbec2820ca2570ec001117a5!OpenDocument "Australian Social Trends" ''Australian Bureau of Statistics''], 1999, Retrieved on June |

Although there were over 250-300 spoken languages with 600 dialects at the start of European settlement, fewer than 200 of these remain in use<ref>[http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.NSF/2f762f95845417aeca25706c00834efa/aadb12e0bbec2820ca2570ec001117a5!OpenDocument "Australian Social Trends" ''Australian Bureau of Statistics''], 1999, Retrieved on 6 June 2008,</ref> – and all but 20 are considered to be endangered.<ref name=autogenerated1>Nathan, D: "Aboriginal Languages of Australia", ''Aboriginal Languages of Australia Virtual Library'', [http://www.dnathan.com/VL/austLang.htm Dnathan.com] 2007</ref> Aborigines today mostly speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create [[Australian Aboriginal English]]. |

||

The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement has been estimated at between 318,000 and 750,000,<ref name="pop_abs">[http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/bfc28642d31c215cca256b350010b3f4!OpenDocument 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2002] Australian Bureau of Statistics |

The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement has been estimated at between 318,000 and 750,000,<ref name="pop_abs">[http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/bfc28642d31c215cca256b350010b3f4!OpenDocument 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2002] Australian Bureau of Statistics 25 January 2002</ref> with the distribution being similar to that of the current Australian population, with the majority living in the south-east, centred along the [[Murray River]].<ref>Pardoe, C: "Becoming Australian: evolutionary processes and biological variation from ancient to modern times", ''Before Farming 2006'', Article 4, 2006</ref> |

||

==Terminology== |

==Terminology== |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

The word [[wikt:aboriginal|aboriginal]] was used in Australia to describe its [[Indigenous peoples]] as early as 1789. It soon became capitalised and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians. |

The word [[wikt:aboriginal|aboriginal]] was used in Australia to describe its [[Indigenous peoples]] as early as 1789. It soon became capitalised and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians. |

||

The word Aboriginal has been in use in |

The word Aboriginal has been in use in English since at least the 17th century to mean "first or earliest known, indigenous," (Latin ''Aborigines'', from ''ab'': from, and ''origo'': origin, beginning),<ref>Originally used by the Romans to denote the (mythical) indigenous people of ancient Italy; see [[Sallust]], [http://www.slu.edu/colleges/AS/languages/classical/latin/tchmat/readers/accreaders/sallust/saltrans1.html ''Bellum Catilinae''], ch. 6.</ref> Strictly speaking, "Aborigine" is the noun and "Aboriginal" the adjectival form; however the latter is often also employed to stand as a noun. |

||

The use of "Aborigine(s)" or "Aboriginal(s)" in this sense, i.e. as a noun, has acquired negative, even derogatory connotations in some sectors of the community, who regard it as insensitive, and even offensive.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infonet.unsw.edu.au/poldoc/racetrea.htm |title=UNSW guide on How to avoid Discriminatory Treatment on Racial of Ethnic Grounds |publisher=Infonet.unsw.edu.au |date= |accessdate=2009 |

The use of "Aborigine(s)" or "Aboriginal(s)" in this sense, i.e. as a noun, has acquired negative, even derogatory connotations in some sectors of the community, who regard it as insensitive, and even offensive.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infonet.unsw.edu.au/poldoc/racetrea.htm |title=UNSW guide on How to avoid Discriminatory Treatment on Racial of Ethnic Grounds |publisher=Infonet.unsw.edu.au |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> The more acceptable and correct expression is "Aboriginal Australians" or "Aboriginal people," though even this is sometimes regarded as an expression to be avoided because of its historical associations with colonialism. "Indigenous Australians" has found increasing acceptance, particularly since the 1980s.<ref>[http://www.trinity.wa.edu.au/plduffyrc/indig/terms.htm Appropriate Terms for Australian Aboriginal People<!-- Bot generated title -->]{{Dead link|date=August 2009}}</ref> |

||

The broad term Aboriginal Australians includes many regional groups that often identify under names from local Indigenous languages. These include: |

The broad term Aboriginal Australians includes many regional groups that often identify under names from local Indigenous languages. These include: |

||

* [[Koori]] (or Koorie) in [[New South Wales]] and [[Victoria (Australia)|Victoria]] ([[Victorian Aborigines]]) |

* [[Koori]] (or Koorie) in [[New South Wales]] and [[Victoria (Australia)|Victoria]] ([[Victorian Aborigines]]) |

||

* [[Ngunnawal]] in the [[Australian Capital Territory]] and surrounding areas of New South Wales |

* [[Ngunnawal]] in the [[Australian Capital Territory]] and surrounding areas of New South Wales |

||

* [[Murri (people)|Murri]] in |

* [[Murri (people)|Murri]] in Queensland |

||

* [[Murrdi]] Southwest and Central |

* [[Murrdi]] Southwest and Central Queensland |

||

* [[Noongar]] in southern |

* [[Noongar]] in southern Western Australia |

||

* [[Yamatji]] in central Western Australia |

* [[Yamatji]] in central Western Australia |

||

* [[Wangai]] in the Western Australian [[Goldfields]] |

* [[Wangai]] in the Western Australian [[Goldfields]] |

||

* [[Nunga]] in southern [[South Australia]] |

* [[Nunga]] in southern [[South Australia]] |

||

* [[Anangu]] in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of |

* [[Anangu]] in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and [[Northern Territory]] |

||

* [[Yapa]] in western central Northern Territory |

* [[Yapa]] in western central Northern Territory |

||

* [[Yolngu]] in eastern [[Arnhem Land]] (NT) |

* [[Yolngu]] in eastern [[Arnhem Land]] (NT) |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

===Torres Strait Islanders=== |

===Torres Strait Islanders=== |

||

{{Main|Torres Strait Islanders}} |

{{Main|Torres Strait Islanders}} |

||

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from Aboriginal traditions. The eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of [[New Guinea]], and speak a [[Papuan language]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=ulk |title=Ethnologue report for language code: ulk |publisher=Ethnologue.com |date= |accessdate=2009 |

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from Aboriginal traditions. The eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of [[New Guinea]], and speak a [[Papuan language]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=ulk |title=Ethnologue report for language code: ulk |publisher=Ethnologue.com |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> Accordingly, they are not generally included under the designation "Aboriginal Australians." This has been another factor in the promotion of the more inclusive term "Indigenous Australians". |

||

Six percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves fully as [[Torres Strait]] Islanders. A further 4% of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as having both [[Torres Strait]] Islanders and Aboriginal heritage.<ref name="ATSI population">''[http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/1301.0Feature%20Article52004?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=1301.0&issue=2004&num=&view= Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population]'', Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004. Retrieved 21 June 2007.</ref> |

Six percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves fully as [[Torres Strait]] Islanders. A further 4% of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as having both [[Torres Strait]] Islanders and Aboriginal heritage.<ref name="ATSI population">''[http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/1301.0Feature%20Article52004?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=1301.0&issue=2004&num=&view= Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population]'', Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004. Retrieved 21 June 2007.</ref> |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

===Black=== |

===Black=== |

||

The term "blacks" has often been applied to Indigenous Australians. This owes more to superficial [[physiognomy]] than [[ethnology]], as it categorises Indigenous Australians with the other [[black people]]s of |

The term "blacks" has often been applied to Indigenous Australians. This owes more to superficial [[physiognomy]] than [[ethnology]], as it categorises Indigenous Australians with the other [[black people]]s of Asia and Africa. In the 1970s, many Aboriginal activists, such as [[Gary Foley]] proudly embraced the term "black", and writer [[Kevin Gilbert (author)|Kevin Gilbert]]'s ground-breaking book from the time was entitled ''Living Black''. The book included interviews with several members of the Aboriginal community including [[Robert Jabanungga]] reflecting on contemporary Aboriginal culture. |

||

In recent years young Indigenous Australians – particularly in urban areas – have increasingly adopted aspects of Black American, African and [[Afro-Caribbean]] culture, creating what has been described as a form of "black transnationalism."<ref name="gibson">Chris Gibson, Peter Dunbar-Hall, ''Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music in Australia'', pp. 120–121 (UNSW Press, 2005).</ref> |

In recent years young Indigenous Australians – particularly in urban areas – have increasingly adopted aspects of Black American, African and [[Afro-Caribbean]] culture, creating what has been described as a form of "black transnationalism."<ref name="gibson">Chris Gibson, Peter Dunbar-Hall, ''Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music in Australia'', pp. 120–121 (UNSW Press, 2005).</ref> |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

{{Main|Australian Aboriginal English|Australian Aboriginal languages|Australian Aboriginal sign languages}} |

{{Main|Australian Aboriginal English|Australian Aboriginal languages|Australian Aboriginal sign languages}} |

||

The [[Australian Aboriginal languages|Indigenous languages]] of mainland Australia and [[Tasmania]] have not been shown to be related to any languages outside Australia. There were more than 250 languages spoken by Indigenous Australians prior to the arrival of Europeans. Most of these are now either [[language death|extinct or moribund]], with only about fifteen languages still being spoken by all age groups.<ref>Zuckermann, Ghil'ad, [http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,25980525-25192,00.html "Aboriginal languages deserve revival"], ''The Australian Higher Education'', |

The [[Australian Aboriginal languages|Indigenous languages]] of mainland Australia and [[Tasmania]] have not been shown to be related to any languages outside Australia. There were more than 250 languages spoken by Indigenous Australians prior to the arrival of Europeans. Most of these are now either [[language death|extinct or moribund]], with only about fifteen languages still being spoken by all age groups.<ref>Zuckermann, Ghil'ad, [http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,25980525-25192,00.html "Aboriginal languages deserve revival"], ''The Australian Higher Education'', 26 August 2009.</ref> |

||

Linguists classify mainland Australian languages into two distinct groups: the [[Pama-Nyungan languages]] and the non-Pama Nyungan. The Pama-Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and are a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western [[Kimberley region of Western Australia|Kimberley]] to the [[Gulf of Carpentaria]], are found a number of groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama-Nyungan family or to each other; these are known as the non-Pama-Nyungan languages. |

Linguists classify mainland Australian languages into two distinct groups: the [[Pama-Nyungan languages]] and the non-Pama Nyungan. The Pama-Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and are a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western [[Kimberley region of Western Australia|Kimberley]] to the [[Gulf of Carpentaria]], are found a number of groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama-Nyungan family or to each other; these are known as the non-Pama-Nyungan languages. |

||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

Aborigines lived as [[Hunter-gatherer]]s. They hunted and foraged for food from the land. Aboriginal society was relatively mobile, or [[nomadic|semi-nomadic]], moving due to the changing food availability found across different areas as seasons changed. The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. The greatest [[population density]] was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the [[River Murray]] valley in particular. |

Aborigines lived as [[Hunter-gatherer]]s. They hunted and foraged for food from the land. Aboriginal society was relatively mobile, or [[nomadic|semi-nomadic]], moving due to the changing food availability found across different areas as seasons changed. The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. The greatest [[population density]] was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the [[River Murray]] valley in particular. |

||

It has been estimated that at the time of first |

It has been estimated that at the time of first European contact, the absolute minimum pre-1788 population was 315,000, while recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 750,000 could have been sustained.<ref name="pop_abs" /> The population was split into 250 individual nations, many of which were in alliance with one another, and within each nation there existed several clans, from as little as 5 or 6 to as many as 30 or 40. Each nation had its own language and a few had several. Thus over 250 languages existed, around 200 of which are now extinct or on the verge of extinction. |

||

===Since British Settlement=== |

===Since British Settlement=== |

||

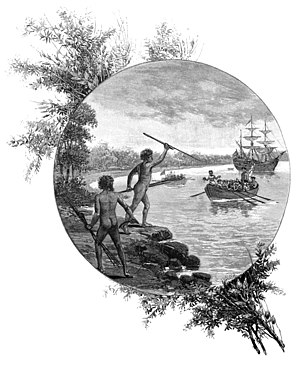

British colonisation of Australia began with the arrival of the [[First Fleet]] in [[Botany Bay]] in 1788. |

British colonisation of Australia began with the arrival of the [[First Fleet]] in [[Botany Bay]] in 1788. |

||

A [[smallpox]] epidemic, which is believed to have been introduced by the [[Makassar|Macassan]]s |

A [[smallpox]] epidemic, which is believed to have been introduced by the [[Makassar|Macassan]]s<ref>Judy Campbell: Invisible invaders. 2002, ISBN 0-522-84939-3</ref> is estimated to have killed up to 90% of the local [[Darug people]] in 1789 and has often been attributed to be caused by white settlers. |

||

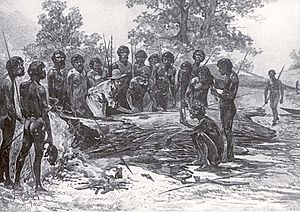

[[Image:Batman signs treaty artist impression.jpg|thumb|right|300px|[[Wurundjeri]] people at the signing of [[Batman's Treaty]], 1835.]] |

[[Image:Batman signs treaty artist impression.jpg|thumb|right|300px|[[Wurundjeri]] people at the signing of [[Batman's Treaty]], 1835.]] |

||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

==== 20th and 21st centuries ==== |

==== 20th and 21st centuries ==== |

||

By 1900 the recorded Indigenous population of Australia had declined to approximately 93,000<ref>{{cite web| title =Year Book Australia, 2002 | publisher |

By 1900 the recorded Indigenous population of Australia had declined to approximately 93,000<ref>{{cite web| title =Year Book Australia, 2002 | publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics | month = | year =2002 | url =http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/bfc28642d31c215cca256b350010b3f4!OpenDocument | accessdate =23 Sep. 2008 }}</ref> although this was only a partial count as both mainstream and tribal Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders were poorly covered with desert Aborigines not counted at all until the 1930s.<ref name="Hughes"/> During the first half of the 20th century, many Indigenous Australians worked as [[stockman|stockmen]] on [[sheep station]]s and [[cattle station]]s. |

||

Although, as British subjects, all Indigenous Australians were nominally entitled to vote, generally only those who "merged" into mainstream society did so. Only Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders from the electoral rolls. Despite the Commonwealth Franchise Act of 1902 that excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901, South Australia insisted that all voters enfranchised within its borders would remain eligible to vote in the Commonwealth and Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders continued to be added to their rolls albeit haphazardly.<ref name="Hughes"/> |

Although, as British subjects, all Indigenous Australians were nominally entitled to vote, generally only those who "merged" into mainstream society did so. Only Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders from the electoral rolls. Despite the Commonwealth Franchise Act of 1902 that excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901, South Australia insisted that all voters enfranchised within its borders would remain eligible to vote in the Commonwealth and Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders continued to be added to their rolls albeit haphazardly.<ref name="Hughes"/> |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

Despite efforts to bar their enlistment, around 500 Indigenous Australians fought for Australia in the First World War.<ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/tv/btn/stories/s1904419.htm ABC.net.au]{{Dead link|date=October 2009}}</ref> |

Despite efforts to bar their enlistment, around 500 Indigenous Australians fought for Australia in the First World War.<ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/tv/btn/stories/s1904419.htm ABC.net.au]{{Dead link|date=October 2009}}</ref> |

||

In the 1930s, the case of [[Dhakiyarr V The King]] saw the first appeal to the [[High Court of Australia|High Court]] by an Aboriginal Australian. In 1934, Dhakiyarr was found to have been wrongly convicted of the murder of a white policeman and the case focused national attention on [[Indigenous rights|Aboriginal rights]] issues. Dhakiyarr disappeared upon release.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://uncommonlives.naa.gov.au/life.asp?lID=2 |title=Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda |publisher=Uncommonlives.naa.gov.au |date= |

In the 1930s, the case of [[Dhakiyarr V The King]] saw the first appeal to the [[High Court of Australia|High Court]] by an Aboriginal Australian. In 1934, Dhakiyarr was found to have been wrongly convicted of the murder of a white policeman and the case focused national attention on [[Indigenous rights|Aboriginal rights]] issues. Dhakiyarr disappeared upon release.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://uncommonlives.naa.gov.au/life.asp?lID=2 |title=Dhakiyarr Wirrpanda |publisher=Uncommonlives.naa.gov.au |date=20 Oct. 2004 |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> In 1938, the 150th anniversary of the arrival of British [[First Fleet]] was marked as a [[Day of Mourning]] and Protest at an Aboriginal meeting in Sydney.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/images/history/pre50s/1930s/dom3.html |title=GF's Koori History Website - Koori History Images - 1930s |publisher=Kooriweb.org |date=26 Jan. 1938 |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

Hundreds of Indigenous Australians served in the Australian armed forces during World War Two - including with the [[Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion]] and The [[Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit]], which were established to guard Australia's North against the threat of Japanese invasion.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/aborigines/indigenous.asp |title=Australian War Memorial - Encyclopedia |publisher=Awm.gov.au |date= |accessdate= |

Hundreds of Indigenous Australians served in the Australian armed forces during World War Two - including with the [[Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion]] and The [[Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit]], which were established to guard Australia's North against the threat of Japanese invasion.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/aborigines/indigenous.asp |title=Australian War Memorial - Encyclopedia |publisher=Awm.gov.au |date= |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

The 1960s was a pivotal decade in the re-assertion of Aboriginal rights. In 1962, Commonwealth legislation specifically gave Aborigines the right to vote in Commonwealth elections. In 1966, [[Vincent Lingiari]] led a famous walk-off of Indigenous employees of Wavehill Station, in protest against poor pay and conditions (later the subject of a [[From Little Things Big Things Grow|Paul Kelly song]]). The landmark [[Australian referendum, 1967 (Aboriginals)|1967 referendum]] called by Prime Minister [[Harold Holt]] allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal people to be included when the country does a count to determine electoral representation. The referendum passed with 90.77% voter support.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://indigenousrights.net.au/timeline.asp?startyear=1960 |title=Timeline |publisher=Indigenousrights.net.au |date= |

The 1960s was a pivotal decade in the re-assertion of Aboriginal rights. In 1962, Commonwealth legislation specifically gave Aborigines the right to vote in Commonwealth elections. In 1966, [[Vincent Lingiari]] led a famous walk-off of Indigenous employees of Wavehill Station, in protest against poor pay and conditions (later the subject of a [[From Little Things Big Things Grow|Paul Kelly song]]). The landmark [[Australian referendum, 1967 (Aboriginals)|1967 referendum]] called by Prime Minister [[Harold Holt]] allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal people to be included when the country does a count to determine electoral representation. The referendum passed with 90.77% voter support.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://indigenousrights.net.au/timeline.asp?startyear=1960 |title=Timeline |publisher=Indigenousrights.net.au |date=13 Jul. 1968 |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

In the controversial 1971 [[Gove land rights case]], Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been ''[[terra nullius]]'' before British settlement, and that no concept of [[native title]] existed in Australian law. In 1971, [[Neville Bonner]] joined the [[Australian Senate]] as a Senator for Queensland for the [[Liberal Party of Australia|Liberal Party]], becoming the first Indigenous Australian in the Federal Parliament. A year later, the [[Aboriginal Tent Embassy]] was established on the steps of [[Politics of Australia|Parliament House]] in [[Canberra]]. In 1976, Sir [[Douglas Nicholls]] was appointed as the 28th Governor of South Australia, the first Aboriginal person appointed to vice-regal office.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.civicsandcitizenship.edu.au/cce/nicholls,9156.html |title=Civics | Sir Douglas Nicholls |publisher=Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au |date= |

In the controversial 1971 [[Gove land rights case]], Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been ''[[terra nullius]]'' before British settlement, and that no concept of [[native title]] existed in Australian law. In 1971, [[Neville Bonner]] joined the [[Australian Senate]] as a Senator for Queensland for the [[Liberal Party of Australia|Liberal Party]], becoming the first Indigenous Australian in the Federal Parliament. A year later, the [[Aboriginal Tent Embassy]] was established on the steps of [[Politics of Australia|Parliament House]] in [[Canberra]]. In 1976, Sir [[Douglas Nicholls]] was appointed as the 28th Governor of South Australia, the first Aboriginal person appointed to vice-regal office.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.civicsandcitizenship.edu.au/cce/nicholls,9156.html |title=Civics | Sir Douglas Nicholls |publisher=Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au |date=14 Jun. 2005 |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

In sport [[Evonne Goolagong Cawley]] became the world number-one ranked tennis player in 1971 and won 14 Grand Slam titles during her career. In 1973 [[Arthur Beetson]] became the first Indigenous Australian to captain his country in any sport when he first led the Australian National Rugby League team, [[the Kangaroos]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thekfaktor.com/speakers/nrl-legends/arthur-beetson-oam/beetson.pdf|title=Arthur Beetson OAM|accessdate=2010 |

In sport [[Evonne Goolagong Cawley]] became the world number-one ranked tennis player in 1971 and won 14 Grand Slam titles during her career. In 1973 [[Arthur Beetson]] became the first Indigenous Australian to captain his country in any sport when he first led the Australian National Rugby League team, [[the Kangaroos]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thekfaktor.com/speakers/nrl-legends/arthur-beetson-oam/beetson.pdf|title=Arthur Beetson OAM|accessdate=3 Mar. 2010}}</ref> In 1982, [[Mark Ella]] became Captain of the Australian National [[Rugby Union]] Team, [[the Wallabies]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rugbyhalloffame.com/pages/ella1997.htm |title=The International Rugby Hall of Fame |publisher=Rugbyhalloffame.com |date=9 Oct. 2007 |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> In 1984, [[Pintupi Nine|a group of]] [[Pintupi]] people who were living a traditional [[hunter-gatherer]] desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the [[Gibson Desert]] in Western Australia and brought in to a settlement. They are believed to be the last [[uncontacted peoples|uncontacted tribe]] in Australia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_1_no_2/exhibition_reviews/colliding_worlds/ |title=Colliding worlds: first contact in the western desert, 1932-1984 |publisher=Recollections.nma.gov.au |date= |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> In 1985, the Australian government returned ownership of [[Uluru]] (named Ayers Rock in Colonial times) to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines. |

||

In 1992, the [[High Court of Australia]] handed down its decision in the [[Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992)|Mabo Case]], declaring the previous legal concept of ''terra nullius'' to be invalid. A Constitutional Convention which selected a Republican model for the Referendum in 1998 included just six Indigenous particpants, leading Monarchist delegate [[Neville Bonner]] to end his contribution to the Convention with his Jagera Tribal Sorry Chant in sadness at the low number of Indigenous representatives. The Republican Model, as well as a proposal for a new Constitutional Preamble which would have included the "honouring" of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders was put to referendum but did not succeed<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/RP/1999-2000/2000rp16.htm |title=First Words: A Brief History of Public Debate on a New Preamble to the Australian Constitution 1991-99 (Research Paper 16 1999-2000) |publisher=Aph.gov.au |date= |accessdate= |

In 1992, the [[High Court of Australia]] handed down its decision in the [[Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992)|Mabo Case]], declaring the previous legal concept of ''terra nullius'' to be invalid. A Constitutional Convention which selected a Republican model for the Referendum in 1998 included just six Indigenous particpants, leading Monarchist delegate [[Neville Bonner]] to end his contribution to the Convention with his Jagera Tribal Sorry Chant in sadness at the low number of Indigenous representatives. The Republican Model, as well as a proposal for a new Constitutional Preamble which would have included the "honouring" of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders was put to referendum but did not succeed<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/RP/1999-2000/2000rp16.htm |title=First Words: A Brief History of Public Debate on a New Preamble to the Australian Constitution 1991-99 (Research Paper 16 1999-2000) |publisher=Aph.gov.au |date= |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

In 1999 the Australian Parliament passed a [[Motion of Reconciliation]] drafted by Prime Minister [[John Howard]] in consultation with Aboriginal Senator [[Aden Ridgeway]] naming mistreatment of Indigenous Australians as the most "blemished chapter in our national history".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20080221_1.htm |title=The History of Apologies Down Under [Thinking Faith - the online journal of the British Jesuits] |publisher=Thinkingfaith.org |date= |accessdate= |

In 1999 the Australian Parliament passed a [[Motion of Reconciliation]] drafted by Prime Minister [[John Howard]] in consultation with Aboriginal Senator [[Aden Ridgeway]] naming mistreatment of Indigenous Australians as the most "blemished chapter in our national history".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20080221_1.htm |title=The History of Apologies Down Under [Thinking Faith - the online journal of the British Jesuits] |publisher=Thinkingfaith.org |date= |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> |

||

In 2000, Aboriginal sprinter [[Cathy Freeman]] lit the [[Olympic flame]] at the opening ceremony of the [[2000 Summer Olympics]] in Sydney. In 2001, the Federal Government dedicated [[Reconciliation Place]] in Canberra. |

In 2000, Aboriginal sprinter [[Cathy Freeman]] lit the [[Olympic flame]] at the opening ceremony of the [[2000 Summer Olympics]] in Sydney. In 2001, the Federal Government dedicated [[Reconciliation Place]] in Canberra. |

||

In 2004, the Australian Government abolished the [[Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission]] amidst allegations of corruption.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aph.gov.au/library/Pubs/RN/2003-04/04rn05.htm |title=APH.gov.au |publisher=APH.gov.au |date= |accessdate= |

In 2004, the Australian Government abolished the [[Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission]] amidst allegations of corruption.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aph.gov.au/library/Pubs/RN/2003-04/04rn05.htm |title=APH.gov.au |publisher=APH.gov.au |date= |accessdate=27 Jun. 2010}}</ref> |

||

In 2007, Prime Minister [[John Howard]] and Indigenous Affairs Minister [[Mal Brough]] launched the [[Northern Territory National Emergency Response]]. In response to the [[Little Children are Sacred]] Report into allegations of child abuse among indigenous communities in the Territory, the government banned alcohol in prescribed communities in the Northern Territory; quarantined a percentage of welfare payments for essential goods purchasing; despatched additional police and medical personnel to the region; and suspended the permit system for access to indigenous communities.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/one-policy-two-camps--the-takeover-rift/2007/10/26/1192941339555.html |title=SMH.au | |

In 2007, Prime Minister [[John Howard]] and Indigenous Affairs Minister [[Mal Brough]] launched the [[Northern Territory National Emergency Response]]. In response to the [[Little Children are Sacred]] Report into allegations of child abuse among indigenous communities in the Territory, the government banned alcohol in prescribed communities in the Northern Territory; quarantined a percentage of welfare payments for essential goods purchasing; despatched additional police and medical personnel to the region; and suspended the permit system for access to indigenous communities.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/one-policy-two-camps--the-takeover-rift/2007/10/26/1192941339555.html |title=SMH.au |work=Sydney Morning Herald |date= |accessdate=27 Jun. 2010}}</ref> |

||

On 13 February 2008, Prime Minister [[Kevin Rudd]] issued a public apology to members of the [[Stolen Generations]] on behalf of the Australian Government. |

On 13 February 2008, Prime Minister [[Kevin Rudd]] issued a public apology to members of the [[Stolen Generations]] on behalf of the Australian Government. |

||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

[[Image:Aboriginal Art Australia.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Rock painting at Ubirr in [[Kakadu National Park]]]] |

[[Image:Aboriginal Art Australia.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Rock painting at Ubirr in [[Kakadu National Park]]]] |

||

There are a large number of [[List of Indigenous Australian group names|tribal divisions]] and [[Australian Aboriginal language|language groups]] in Aboriginal |

There are a large number of [[List of Indigenous Australian group names|tribal divisions]] and [[Australian Aboriginal language|language groups]] in Aboriginal Australia, and, correspondingly, a wide variety of diversity exists within cultural practices. However, there are some similarities between cultures. |

||

===Belief systems=== |

===Belief systems=== |

||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

{{See also|Australian Aboriginal mythology}} |

{{See also|Australian Aboriginal mythology}} |

||

Religious demography among Indigenous Australians is not conclusive because the methodology of the census is not always well-suited to obtaining accurate information on Aboriginal people.<ref>Tatz, C. (1999, 2005). ''Aboriginal Suicide Is Different.'' Aboriginal Studies Press. [http://www.aic.gov.au/crc/reports/tatz/ AIC.gov.au]</ref> The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practised some form of |

Religious demography among Indigenous Australians is not conclusive because the methodology of the census is not always well-suited to obtaining accurate information on Aboriginal people.<ref>Tatz, C. (1999, 2005). ''Aboriginal Suicide Is Different.'' Aboriginal Studies Press. [http://www.aic.gov.au/crc/reports/tatz/ AIC.gov.au]</ref> The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practised some form of Christianity; 16 percent listed no religion. The 2001 census contained no comparable updated data.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/AD25AA55EB7FDC75CA25697E0018FD84?opendocument |title=Australian Bureau of Statistics – Religion |publisher=Abs.gov.au |date=20 Jan. 2006 |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> There has also been an increase in the number of followers of [[Islam in Australia|Islam]] among the Indigenous Australian community.<ref>{{cite news | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2902315.stm | title = Aborigines turn to Islam | work=BBC |date=31 March 2003 | author=Phil Mercer | accessdate = 25 May 2007}}</ref> This growing community includes high-profile members such as the boxer, [[Anthony Mundine]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/a-new-faith-for-kooris/2007/05/03/1177788310619.html |title=A new faith for Kooris |work=Sydney Morning Herald |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> |

||

Aborigines traditionally adhered to [[animist]] spiritual frameworks. Within Aboriginal belief systems, a formative epoch known as 'the [[Dreamtime]]' stretches back into the distant past when the creator ancestors known as the [[First Peoples]] |

Aborigines traditionally adhered to [[animist]] spiritual frameworks. Within Aboriginal belief systems, a formative epoch known as 'the [[Dreamtime]]' stretches back into the distant past when the creator ancestors known as the [[First Peoples]] travelled across the land, creating and naming as they went.<ref>Andrews, M. (2004) 'The Seven Sisters', Spinifex Press, North Melbourne, p. 424</ref> Indigenous Australia's [[oral tradition]] and religious values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in this [[Dreamtime]]. |

||

The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present-day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with its own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. Major [[ancestral]] spirits include the [[Rainbow Serpent]], [[Baiame]], [[Dirawong]] and [[Bunjil]]. |

The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present-day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with its own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. Major [[ancestral]] spirits include the [[Rainbow Serpent]], [[Baiame]], [[Dirawong]] and [[Bunjil]]. |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

{{Main|Indigenous Australian music}} |

{{Main|Indigenous Australian music}} |

||

The various Indigenous Australian communities developed unique musical instruments and folk styles. The [[didgeridoo]], which is widely thought to be a stereotypical instrument of Aboriginal people, was traditionally played by people of only the eastern [[Kimberley (Western Australia)|Kimberley]] region and [[Arnhem Land]] (such as the Yolngu), and then by only the men.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aboriginalarts.co.uk/historyofthedidgeridoo.html |title=History of the Didgeridoo Yidaki |publisher=Aboriginalarts.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2009 |

The various Indigenous Australian communities developed unique musical instruments and folk styles. The [[didgeridoo]], which is widely thought to be a stereotypical instrument of Aboriginal people, was traditionally played by people of only the eastern [[Kimberley (Western Australia)|Kimberley]] region and [[Arnhem Land]] (such as the Yolngu), and then by only the men.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aboriginalarts.co.uk/historyofthedidgeridoo.html |title=History of the Didgeridoo Yidaki |publisher=Aboriginalarts.co.uk |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> [[Clapping sticks]] are probably the more ubiquitous musical instrument, especially because they help maintain rhythm for songs. |

||

Contemporary Australian aboriginal music is predominantly of the [[country music]] genre. Most Indigenous radio stations – particularly in metropolitan areas – serve a double purpose as the local country-music station. More recently, [[List of Indigenous Australian musicians|Indigenous Australian musicians]] have branched into [[rock and roll]], [[hip hop]] and [[reggae]]. One of the most well known modern bands is [[Yothu Yindi]] playing in a style which has been called [[Aboriginal rock]]. |

Contemporary Australian aboriginal music is predominantly of the [[country music]] genre. Most Indigenous radio stations – particularly in metropolitan areas – serve a double purpose as the local country-music station. More recently, [[List of Indigenous Australian musicians|Indigenous Australian musicians]] have branched into [[rock and roll]], [[hip hop]] and [[reggae]]. One of the most well known modern bands is [[Yothu Yindi]] playing in a style which has been called [[Aboriginal rock]]. |

||

Amongst young Australian aborigines, [[African American|African-American]] and Aboriginal [[hip hop]] music and clothing is popular.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theage.com.au/news/music/the-new-corroboree/2006/03/30/1143441270792.html?page=fullpage |title=The new corroboree - Music - Entertainment | |

Amongst young Australian aborigines, [[African American|African-American]] and Aboriginal [[hip hop]] music and clothing is popular.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theage.com.au/news/music/the-new-corroboree/2006/03/30/1143441270792.html?page=fullpage |title=The new corroboree - Music - Entertainment |work=The Age |location=Australia |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> Aboriginal boxing champion and former rugby league player [[Anthony Mundine]] identified US rapper [[Tupac Shakur]] as a personal inspiration, after Mundine's release of his 2007 single, ''Platinum Ryder''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/music/the-man-must-make-his-music/2007/03/25/1174761263365.html |title=The Man must make his music - Music - Entertainment |work=Sydney Morning Herald |date=25 Mar. 2007 |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref> |

||

===Art=== |

===Art=== |

||

| Line 193: | Line 193: | ||

[[Image:Aboriginal football.jpg|Popular with Indigenous Australian communities. |260px|thumb|right|An Indigenous community [[Australian rules football]] game.]] |

[[Image:Aboriginal football.jpg|Popular with Indigenous Australian communities. |260px|thumb|right|An Indigenous community [[Australian rules football]] game.]] |

||

The [[Djab wurrung]] and [[Jardwadjali]] people of western Victoria once participated in the traditional game of [[Marn Grook]], a type of |

The [[Djab wurrung]] and [[Jardwadjali]] people of western Victoria once participated in the traditional game of [[Marn Grook]], a type of football played with a ball made of [[possum]] hide.<ref>[http://abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/09/21/2039577.htm?section=australia Kids play "kick to kick" -1850s style] from abc.net.au</ref> |

||

The game is believed by some to have inspired [[Tom Wills]], inventor of the code of [[Australian rules football]], a popular Australian winter sport. The Wills family had strong links to Indigenous people and Wills coached the first Australian cricket side to tour England, the [[Australian Aboriginal cricket team in England in 1868]].{{Citation needed|date=August 2009|content challenged by an anon, no source}} |

The game is believed by some to have inspired [[Tom Wills]], inventor of the code of [[Australian rules football]], a popular Australian winter sport. The Wills family had strong links to Indigenous people and Wills coached the first Australian cricket side to tour England, the [[Australian Aboriginal cricket team in England in 1868]].{{Citation needed|date=August 2009|content challenged by an anon, no source}} |

||

| Line 202: | Line 202: | ||

The ruling was a three-part definition comprising descent, self-identification and community identification. The first part - descent - was genetic descent and unambiguous, but led to cases where a lack of records to prove ancestry excluded some. Self- and community identification were more problematic as they meant that an Indigenous person separated from her or his community due to a family dispute could no longer identify as Aboriginal. |

The ruling was a three-part definition comprising descent, self-identification and community identification. The first part - descent - was genetic descent and unambiguous, but led to cases where a lack of records to prove ancestry excluded some. Self- and community identification were more problematic as they meant that an Indigenous person separated from her or his community due to a family dispute could no longer identify as Aboriginal. |

||

As a result there arose court cases throughout the 1990s where excluded people demanded that their Aboriginality be recognised. In 1995, Justice Drummond ruled "..either genuine self-identification as Aboriginal alone or Aboriginal communal recognition as such by itself may suffice, according to the circumstances." This contributed to an increase of 31% in the number of people identifying as Indigenous Australians in the 1996 census when compared to the 1991 census.<ref name=" Bourke ">{{cite web | last = Greg Gardiner | first = Eleanor Bourke: | year = 2002 | title = Indigenous Populations, Mixed Discourses and Identities pdf | work |

As a result there arose court cases throughout the 1990s where excluded people demanded that their Aboriginality be recognised. In 1995, Justice Drummond ruled "..either genuine self-identification as Aboriginal alone or Aboriginal communal recognition as such by itself may suffice, according to the circumstances." This contributed to an increase of 31% in the number of people identifying as Indigenous Australians in the 1996 census when compared to the 1991 census.<ref name=" Bourke ">{{cite web | last = Greg Gardiner | first = Eleanor Bourke: | year = 2002 | title = Indigenous Populations, Mixed Discourses and Identities pdf | work=People and Place Volume 8 No 2 [[Monash University]] | url = http://elecpress.monash.edu.au/pnp/free/pnpv8n2/v8n2_5gardiner.pdf | accessdate = 16 December 2009 }}</ref> |

||

Judge Merkel in 1998 defined Aboriginal descent as technical rather than real - thereby eliminating a genetic requirement.<ref>Defining Indigenousness and asserting Aboriginal identity. Tyson Yunkaporta |

Judge Merkel in 1998 defined Aboriginal descent as technical rather than real - thereby eliminating a genetic requirement.<ref>Defining Indigenousness and asserting Aboriginal identity. Tyson Yunkaporta 6 Jun 2007.</ref> This decision established that anyone can classify him or herself legally as an Aboriginal, provided he or she is accepted as such by his or her community. |

||

==== Inclusion in the National Census ==== |

==== Inclusion in the National Census ==== |

||

| Line 211: | Line 211: | ||

As there is no formal procedure for any community to record acceptance, the primary method of determining Indigenous population is from self-identification on census forms. |

As there is no formal procedure for any community to record acceptance, the primary method of determining Indigenous population is from self-identification on census forms. |

||

Until 1967 official Australian population statistics excluded "full-blood aboriginal natives" in accordance with section 127 of the Australian Constitution, even though many such people were actually counted. The size of the excluded population was generally separately estimated. "Half-caste aboriginal natives" were shown separately up to the 1966 census, but since 1971 there has been no provision on the forms to differentiate 'full' from 'part' Indigenous or to identify non-Indigenous persons accepted by Indigenous communities, but who have no genetic descent.<ref name="Gardiner-Garden">{{cite web |url=http://www.aph.gov.au/LIBRARY/pubs/rn/2000-01/01RN18.htm |title=The Definition of Aboriginality |accessdate=2008 |

Until 1967 official Australian population statistics excluded "full-blood aboriginal natives" in accordance with section 127 of the Australian Constitution, even though many such people were actually counted. The size of the excluded population was generally separately estimated. "Half-caste aboriginal natives" were shown separately up to the 1966 census, but since 1971 there has been no provision on the forms to differentiate 'full' from 'part' Indigenous or to identify non-Indigenous persons accepted by Indigenous communities, but who have no genetic descent.<ref name="Gardiner-Garden">{{cite web |url=http://www.aph.gov.au/LIBRARY/pubs/rn/2000-01/01RN18.htm |title=The Definition of Aboriginality |accessdate=5 Feb. 2008 |author=John Gardiner-Garden |publisher=Parliament of Australia |work=Parliamentary Library |date=5 Oct. 2000 }}</ref> |

||

==== Demographics ==== |

==== Demographics ==== |

||

{{Main|Demographics of Australia}} |

{{Main|Demographics of Australia}} |

||

The [[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] 2005 [[snapshot]] of Australia showed that the Indigenous population had grown at twice the rate of the overall population since 1996 when the Indigenous population stood at 283,000. As of June 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident Indigenous population to be 458,520 (2.4% of Australia's total), 90% of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6% Torres Strait Islander and the remaining 4% being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage. Much of the increase since 1996 can be attributed to greater numbers of people identifying themselves as Aborigines. Changed definitions of aboriginality and positive discrimination via material benefits have been cited as contributing to a movement to indigenous identification.<ref name="Hughes">{{cite web | last = Hughes | first = Helen | date = November 2008 | title = Who Are Indigenous Australians? | work |

The [[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] 2005 [[snapshot]] of Australia showed that the Indigenous population had grown at twice the rate of the overall population since 1996 when the Indigenous population stood at 283,000. As of June 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident Indigenous population to be 458,520 (2.4% of Australia's total), 90% of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6% Torres Strait Islander and the remaining 4% being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage. Much of the increase since 1996 can be attributed to greater numbers of people identifying themselves as Aborigines. Changed definitions of aboriginality and positive discrimination via material benefits have been cited as contributing to a movement to indigenous identification.<ref name="Hughes">{{cite web | last = Hughes | first = Helen | date = November 2008 | title = Who Are Indigenous Australians? | work=[[Quadrant (magazine)|Quadrant]] | url = https://www.quadrant.org.au/magazine/issue/2008/451/who-are-indigenous-australians | accessdate = 16 December 2009 }}</ref> |

||

In the 2006 Census, 407,700 respondents declared they were Aboriginal, 29,512 declared they were [[Torres Strait Islander]], and a further 17,811 declared they were both Aboriginal and [[Torres Strait Islanders]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/a0dbf953e41d83d3ca257306000d514b!OpenDocument |title=2914.0.55.002 - 2006 Census of Population and Housing: Media Releases and Fact Sheets, 2006 |publisher=Abs.gov.au |date= |accessdate= |

In the 2006 Census, 407,700 respondents declared they were Aboriginal, 29,512 declared they were [[Torres Strait Islander]], and a further 17,811 declared they were both Aboriginal and [[Torres Strait Islanders]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/a0dbf953e41d83d3ca257306000d514b!OpenDocument |title=2914.0.55.002 - 2006 Census of Population and Housing: Media Releases and Fact Sheets, 2006 |publisher=Abs.gov.au |date= |accessdate=12 Oct. 2009}}</ref> After adjustments for undercount, the indigenous population as of end June 2006 was estimated to be 517,200, representing about 2.5% of the population.<ref name=ABS2008YBindigenous>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/bb8db737e2af84b8ca2571780015701e/68AE74ED632E17A6CA2573D200110075?opendocument|title=Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population|work=1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=7 February 2008|accessdate=3 Jan. 2009}}</ref> |

||

Based on Census data at 30 June 2006, the preliminary estimate of Indigenous resident population of Australia <!-- This isn't quite the same as the Census figure itself – estimated population includes an adjustment for undercount, and because the reference date is about a month before the actual Census date --> was 517,200, broken down as follows: |

Based on Census data at 30 June 2006, the preliminary estimate of Indigenous resident population of Australia <!-- This isn't quite the same as the Census figure itself – estimated population includes an adjustment for undercount, and because the reference date is about a month before the actual Census date --> was 517,200, broken down as follows: |

||

*[[New South Wales]] – 148,200 |

*[[New South Wales]] – 148,200 |

||

* |

*Queensland – 146,400 |

||

* |

*Western Australia – 77,900 |

||

*[[Northern Territory]] – 66,600 |

*[[Northern Territory]] – 66,600 |

||

*[[Victoria (Australia)|Victoria]] – 30,800 |

*[[Victoria (Australia)|Victoria]] – 30,800 |

||

| Line 242: | Line 242: | ||

Throughout the history of the continent, there have been many different [[List of Indigenous Australian group names|Aboriginal groups]], each with its own individual [[Australian Aboriginal languages|language]], culture, and belief structure. |

Throughout the history of the continent, there have been many different [[List of Indigenous Australian group names|Aboriginal groups]], each with its own individual [[Australian Aboriginal languages|language]], culture, and belief structure. |

||

At the time of British settlement, there were over 200 distinct languages.<!-- TRANSLATION PLEASE: (in the technical linguistic sense of non-mutually intelligible speech varieties)--> <!-- DEAD LINK: ACCESS DENIED,<ref>Australian Aboriginal languages. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved |

At the time of British settlement, there were over 200 distinct languages.<!-- TRANSLATION PLEASE: (in the technical linguistic sense of non-mutually intelligible speech varieties)--> <!-- DEAD LINK: ACCESS DENIED,<ref>Australian Aboriginal languages. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 October 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9109808</ref> --> |

||

There are an indeterminate number of Indigenous communities, comprising several hundred groupings. Some communities, cultures or groups may be inclusive of others and alter or overlap; significant changes have occurred in the generations after colonisation. |

There are an indeterminate number of Indigenous communities, comprising several hundred groupings. Some communities, cultures or groups may be inclusive of others and alter or overlap; significant changes have occurred in the generations after colonisation. |

||

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

The word 'community' is often used to describe groups identifying by kinship, language or belonging to a particular place or 'country'. A community may draw on separate cultural values and individuals can conceivably belong to a number of communities within Australia; identification within them may be adopted or rejected. |

The word 'community' is often used to describe groups identifying by kinship, language or belonging to a particular place or 'country'. A community may draw on separate cultural values and individuals can conceivably belong to a number of communities within Australia; identification within them may be adopted or rejected. |

||

An individual community may identify itself by many names, each of which can have alternate |

An individual community may identify itself by many names, each of which can have alternate English spellings. The largest Aboriginal communities - the [[Pitjantjatjara]], the [[Arrernte]], the [[Luritja]] and the [[Warlpiri]] - are all from [[Central Australia]]. |

||

{{Expand section|date=June 2008}} |

{{Expand section|date=June 2008}} |

||

| Line 260: | Line 260: | ||

==Contemporary issues== |

==Contemporary issues== |

||

The Indigenous Australian population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number (27% as of 2002<ref name = "2002 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/00000000000000000000000000000000/294322bc5648ead8ca256f7200833040!OpenDocument |title=Australian Bureau of Statistics |publisher=Abs.gov.au |date= |accessdate=2009 |

The Indigenous Australian population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number (27% as of 2002<ref name = "2002 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/00000000000000000000000000000000/294322bc5648ead8ca256f7200833040!OpenDocument |title=Australian Bureau of Statistics |publisher=Abs.gov.au |date= |accessdate=9 Aug. 2009}}</ref>) live in remote settlements often located on the site of former church [[mission (station)|missions]]. The health and economic difficulties facing both groups are substantial. Both the remote and urban populations have adverse ratings on a number of social indicators, including health, education, unemployment, poverty and crime.<ref name = "Year Book 2005">Australian Bureau of Statistics. [http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/1a79e7ae231704f8ca256f720082feb9!OpenDocument Year Book Australia 2005]</ref> |

||

In 2004 former Prime Minister [[John Howard]] initiated contracts with Aboriginal communities, where substantial financial benefits are available in return for commitments such as ensuring children attend school. These contracts are known as Shared Responsibility Agreements. This saw a political shift from 'self determination' for Aboriginal communities to 'mutual obligation',<ref name = "Mutual obligation, shared responsibility agreements & Indigenous health strategy">Mutual obligation, shared responsibility agreements & Indigenous health strategy, Ian PS Anderson [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1626072 NIH.gov]</ref> which has been criticised as a "paternalistic and dictatorial arrangement".<ref name = "Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice">Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice, Larissa Behrendt, The Age newspaper, |

In 2004 former Prime Minister [[John Howard]] initiated contracts with Aboriginal communities, where substantial financial benefits are available in return for commitments such as ensuring children attend school. These contracts are known as Shared Responsibility Agreements. This saw a political shift from 'self determination' for Aboriginal communities to 'mutual obligation',<ref name = "Mutual obligation, shared responsibility agreements & Indigenous health strategy">Mutual obligation, shared responsibility agreements & Indigenous health strategy, Ian PS Anderson [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1626072 NIH.gov]</ref> which has been criticised as a "paternalistic and dictatorial arrangement".<ref name = "Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice">Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice, Larissa Behrendt, The Age newspaper, 8 December 2004 [http://www.smh.com.au/news/Opinion/Nothing-mutual-about-denying-Aborigines-a-voice/2004/12/07/1102182295283.html SMH.com.au]</ref> |

||

The "Mutual Obligation" concept was introduced for all Australians in receipt of welfare benefits and who are not disabled or elderly.<ref>[http://www.centrelink.gov.au/internet/internet.nsf/payments/newstart_mutual_obligation.htm Mutual Obligation Requirements<!-- Bot generated title -->]{{Dead link|date=August 2009}}</ref> Notably, just prior to a [[Australian general election, 2007|federal election]] being called, John Howard in a speech at the [[Sydney Institute]] on |

The "Mutual Obligation" concept was introduced for all Australians in receipt of welfare benefits and who are not disabled or elderly.<ref>[http://www.centrelink.gov.au/internet/internet.nsf/payments/newstart_mutual_obligation.htm Mutual Obligation Requirements<!-- Bot generated title -->]{{Dead link|date=August 2009}}</ref> Notably, just prior to a [[Australian general election, 2007|federal election]] being called, John Howard in a speech at the [[Sydney Institute]] on 11 October 2007 acknowledged some of the failures of the previous policies of his government and said "We must recognise the distinctiveness of Indigenous identity and culture and the right of Indigenous people to preserve that heritage. The crisis of Indigenous social and cultural disintegration requires a stronger affirmation of Indigenous identity and culture as a source of dignity, self-esteem and pride." |

||

===Stolen Generations=== |

===Stolen Generations=== |

||

{{Main|Stolen Generations}} |

{{Main|Stolen Generations}} |

||

The Stolen Generations were those children of |

The Stolen Generations were those children of Australian Aboriginal and [[Torres Strait Islander]] descent who were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian [[Australian Government|Federal]] and [[Australian states and territories|State]] [[government]] agencies and [[Mission (Christian)|church mission]]s, under [[act of parliament|acts of their respective parliaments]].<ref name="stolen62">''Bringing them Home'', |

||

[http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen62.html Appendices listing and interpretation of state acts regarding 'Aborigines']: [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen63.html Appendix 1.1 NSW]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen64.html Appendix 1.2 ACT]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen65.html Appendix 2 Victoria]; |

[http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen62.html Appendices listing and interpretation of state acts regarding 'Aborigines']: [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen63.html Appendix 1.1 NSW]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen64.html Appendix 1.2 ACT]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen65.html Appendix 2 Victoria]; |

||

[http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen66.html Appendix 3 Queensland]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen67.html Tasmania]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen68.html Appendix 5 Western Australia]; |

[http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen66.html Appendix 3 Queensland]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen67.html Tasmania]; [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen68.html Appendix 5 Western Australia]; |

||

| Line 275: | Line 275: | ||

|url= http://www.dreamtime.net.au/indigenous/family.cfm#bi |

|url= http://www.dreamtime.net.au/indigenous/family.cfm#bi |

||

|title= Indigenous Australia: Family |

|title= Indigenous Australia: Family |

||

|accessdate= |

|accessdate= 28 Mar. 2008 |

||

|author= |

|author=Australian Museum |

||

|authorlink= Australian Museum |

|authorlink= Australian Museum |

||

|year= 2004 |

|year= 2004 |

||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

| first = Peter |

| first = Peter |

||

| title = The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969 |

| title = The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969 |

||

| publisher |

| publisher=Department of Aboriginal Affairs (New South Wales government) |

||

| year = 1981 |

| year = 1981 |

||

| url = http://www.daa.nsw.gov.au/publications/StolenGenerations.pdf |

| url = http://www.daa.nsw.gov.au/publications/StolenGenerations.pdf |

||

| format=PDF| isbn = 0-646-46221-0}}</ref> although, in some places, children were still being taken in the 1970s.<ref>In its submission to the ''Bringing Them Home'' report, the Victorian government stated that "despite the apparent recognition in government reports that the interests of Indigenous children were best served by keeping them in their own communities, the number of Aboriginal children forcibly removed continued to increase, rising from 220 in 1973 to 350 in 1976" [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen10.html ''Bringing Them Home'': "Victoria".]</ref> |

| format=PDF| isbn = 0-646-46221-0}}</ref> although, in some places, children were still being taken in the 1970s.<ref>In its submission to the ''Bringing Them Home'' report, the Victorian government stated that "despite the apparent recognition in government reports that the interests of Indigenous children were best served by keeping them in their own communities, the number of Aboriginal children forcibly removed continued to increase, rising from 220 in 1973 to 350 in 1976" [http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/rsjproject/rsjlibrary/hreoc/stolen/stolen10.html ''Bringing Them Home'': "Victoria".]</ref> |

||

On February |

On 13 February 2008, the federal government of Australia, led by Prime Minister [[Kevin Rudd]], issued a formal apology to the Indigenous Australians over the [[Stolen Generations]].<ref>[http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/rudd-says-sorry/2008/02/13/1202760342960.html "Rudd says sorry"], Dylan Welch, ''Sydney Morning Herald'' 13 February 2008.</ref> |

||

===Political representation=== |

===Political representation=== |

||

| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

{{See also|Voting rights of Australian Aboriginals}} |

{{See also|Voting rights of Australian Aboriginals}} |

||

Under Section 41 of the Australian Constitution Aboriginal Australians always had the legal right to vote in Australian Commonwealth elections if their State granted them that right. This meant that all Aborigines outside Queensland and Western Australia had a legal right to vote. The right of indigenous ex-servicemen to vote was affirmed in 1949 and all Indigenous Australians gained the unqualified right to vote in Federal elections in 1962.<ref name="aec.gov.au">{{cite web|url=http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/indigenous_vote/indigenous.htm |title=AEC.gov.au |publisher=AEC.gov.au |date= |

Under Section 41 of the Australian Constitution Aboriginal Australians always had the legal right to vote in Australian Commonwealth elections if their State granted them that right. This meant that all Aborigines outside Queensland and Western Australia had a legal right to vote. The right of indigenous ex-servicemen to vote was affirmed in 1949 and all Indigenous Australians gained the unqualified right to vote in Federal elections in 1962.<ref name="aec.gov.au">{{cite web|url=http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/indigenous_vote/indigenous.htm |title=AEC.gov.au |publisher=AEC.gov.au |date=25 Oct. 2007 |accessdate=27 Jun. 2010}}</ref> Unlike other Australians, however, voting was not made compulsory for Indigenous people. |

||

It was not until the repeal of Section 127 of the Australian Constitution in 1967 that Indigenous Australians were counted in the population for the purpose of distribution of electoral seats. Only two Indigenous Australians have been elected to the Australian Parliament, [[Neville Bonner]] (1971–1983) and [[Aden Ridgeway]] (1999–2005). There are currently no Indigenous Australians in the Australian Parliament, however a number of indigenous people represent electorates at State and Territorial level, and South Australia has had an Aboriginal Governor, Sir [[Douglas Nicholls]]. The first Indigenous Australian to serve as a minister in any government was [[Ernie Bridge]], who entered the Western Australian Parliament in 1980. The first woman minister was [[Marion Scrymgour]], who was appointed to the Northern Territory ministry in 2002 (she became Deputy Chief Minister in 2008).<ref name="aec.gov.au"/> |

It was not until the repeal of Section 127 of the Australian Constitution in 1967 that Indigenous Australians were counted in the population for the purpose of distribution of electoral seats. Only two Indigenous Australians have been elected to the Australian Parliament, [[Neville Bonner]] (1971–1983) and [[Aden Ridgeway]] (1999–2005). There are currently no Indigenous Australians in the Australian Parliament, however a number of indigenous people represent electorates at State and Territorial level, and South Australia has had an Aboriginal Governor, Sir [[Douglas Nicholls]]. The first Indigenous Australian to serve as a minister in any government was [[Ernie Bridge]], who entered the Western Australian Parliament in 1980. The first woman minister was [[Marion Scrymgour]], who was appointed to the Northern Territory ministry in 2002 (she became Deputy Chief Minister in 2008).<ref name="aec.gov.au"/> |

||

[[ATSIC]], a representative body of Aborigine and Torres Strait Islanders, was set up in 1990 under the [[Bob Hawke|Hawke]] government. In 2004, the [[Howard government]] disbanded ATSIC and replaced it with an appointed network of 30 Indigenous Coordination Centres that administer Shared Responsibility Agreements and Regional Partnership Agreements with Aboriginal communities at a local level.<ref name="rcc">{{cite web|url=http://www.oipc.gov.au/About_OIPC/Indigenous_Affairs_Arrangements/4Administration.asp|title=Coordination and engagement at regional and national levels|accessdate= |

[[ATSIC]], a representative body of Aborigine and Torres Strait Islanders, was set up in 1990 under the [[Bob Hawke|Hawke]] government. In 2004, the [[Howard government]] disbanded ATSIC and replaced it with an appointed network of 30 Indigenous Coordination Centres that administer Shared Responsibility Agreements and Regional Partnership Agreements with Aboriginal communities at a local level.<ref name="rcc">{{cite web|url=http://www.oipc.gov.au/About_OIPC/Indigenous_Affairs_Arrangements/4Administration.asp|title=Coordination and engagement at regional and national levels|accessdate=17 May 2006|publisher=Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination |year=2006|work=Administration}}</ref> |

||

In October 2007, just prior to the calling of a [[Australian general election, 2007|federal election]], the then Prime Minister, John Howard, revisited the idea of bringing a referendum to seek recognition of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution (his government first sought to include recognition of Aborigines in the Preamble to the Constitution in a 1999 referendum). His 2007 announcement was seen by some as a surprising adoption of the importance of the symbolic aspects of the reconciliation process, and reaction was mixed. The ALP initially supported the idea, however [[Kevin Rudd]] withdrew this support just prior to the election - earning stern rebuke from activist [[Noel Pearson]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,22809264-601,00.html |title=Noel Pearson's statement on Kevin Rudd | The Australian |publisher=Theaustralian.news.com.au |date= |