Protest song: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Reverting possible vandalism by 168.216.103.66 to version by Coastergeekperson04. False positive? Report it. Thanks, User:ClueBot. (288992) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{globalize/USA}} |

{{globalize/USA}} |

||

A '''protest song''' is a song which [[protest]]s perceived problems in society and with world conflicts. Every major movement in Western history has been accompanied by its own collection of |

A '''protest song''' is a song which [[protest]]s perceived problems in society and with world conflicts. Every major movement in Western history has been accompanied by its own collection of protest songs, from slave [[emancipation]] to women's [[suffrage]], the [[labor movement]], [[civil rights]], the anti-war movement, the [[feminist]] movement, the environmental movement. Over time, the songs have come to protest more abstract, moral issues, such as [[injustice]], [[racial discrimination]], the morality of [[war]] in general (as opposed to purely protesting individual wars), [[globalization]], [[inflation]], [[social inequalities]], and [[incarceration]]. Such songs generally become more popular during times of social disruption among social groups. The oldest European protest song on record is "The Cutty Wren" from the [[English peasants' revolt of 1381]] against feudal oppression.<ref>{{cite web |

||

| url = http://unionsong.com/u080.html |

|||

| title = The Cutty Wren |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = Union Songs |

|||

| more early history should be added here}}</ref> |

|||

Some of the most internationally famous examples of protest songs come from the U.S. They include "[[We Shall Overcome]]" (a song popular in the labor movement and later the [[Civil Rights movement]]), [[Bob Dylan]]'s "[[Blowin' in the Wind]] and [[Marvin Gaye]]'s "[[What's Going On]]". Many key figures world-wide have contributed to their own nations' traditions of protest music, such as [[Victor Jara]] in Latin America, [[Silvio Rodríguez]] in Cuba and [[Vuyisile Mini]] in anti-apartheid South Africa. Protest songs are generally associated with folk music, but more recently they have been produced in all genres of music. |

|||

==North American songs of protest== |

|||

===Eighteenth century=== |

|||

Prior to the [[American Revolutionary War]], political songs appeared in the mid 1700s America in response to social injustices (such as the struggle between classes) and political issues (such as the opposing ideologies of the [[Patriot (American Revolution)|Whigs]] and [[Tories]], and issues such as the stamp act). "American Taxation" written by Peter St. John and sung to the tune of "[[The British Grenadiers]]" was one such song which protested against "the cruel lords of Britain" who were "striving after our rights to take away, and rob us of our charter, in North America".<ref>{{cite web| url = http://musicanet.org/robokopp/usa/whilirel.htm| title = "American Taxation" lyrics| accessdate= 2007-10-30| publisher = musicanet.org}}</ref> "Come On, Brave Boys" (1734), "The American Hero" by [[Andrew Law]], "Free America" by Dr. Joseph Warren, and "Liberty Song" by John Dickinson (1768) all equally protested against the British rule in America, and called for freedom.<ref name= mcgath> {{cite web|url= http://www.mcgath.com/freesongs.html| title= Songs of Freedom| accessdate= 2007-11-03|Publisher= Gary McGath|}}</ref> The earliest known American election campaign song was "God Save George Washington", issued in 1780 and sung to the tune of "[[God Save the King]]", a common practice as the majority of political songs at the time were based on already well known music and were often published with only the lyrics in newspapers and broadsides, and a "sung to the tune of" direction.<ref>{{cite web|| url = http://parlorsongs.com/issues/2002-11/thismonth/feature.asp| title = Political and Campaign Songs In American Popular Music |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03| publisher = The Parlor Songs Association, Inc.}}</ref> |

|||

"Rights of Woman" (1795), sung to the tune of "[[God Save the King]]", written anonymously by "A Lady", and published in the ''Philadelphia Minerva'', October 17, 1795, is one of the earliest American songs pointing out that rights apply equally to both sexes.<ref name= mcgath> {{cite web|url= http://www.mcgath.com/freesongs.html| title= Songs of Freedom| accessdate= 2007-11-03|Publisher= Gary McGath|}}</ref> The song contains many outspoken declarations of protest, and slogans such as "God save each Female's right", "Woman is free" and "Let woman have a share". |

|||

===Nineteenth century=== |

|||

[[Image:The Old Granite State sheet music cover.jpg|thumb|The Hutchinson Family Singers; a 19th-century American family singing group who sang about political causes in four-part harmony]] |

|||

The nineteenth century saw a number of protest songs being written, for the most part, on three key issues: War, and the [[American Civil War]] in particular (such as "[[Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye]]" from Ireland, and its American variant, "[[When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again]]", among others); The [[abolition]] of [[slavery]] ("[[Song of the Abolitionist]]"<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african/afam007.html |

|||

| title = The African-American Mosaic |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = The Library of Congress |

|||

}}</ref> and "[[No More Auction Block for Me]]",<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.negrospirituals.com/news-song/no_more_auction_block_for_me.htm |

|||

| title = NO MORE AUCTION BLOCK FOR ME Official Site of Negro Spirituals, antique Gospel Music |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = Spiritual Workshop |

|||

}}</ref> among others) and [[Women's suffrage]], both for and against in both Britain and the U.S. |

|||

Perhaps the most famous voices of protest at the time - in America at least - were the [[Hutchinson Family Singers]]. From 1839, the [[Hutchinson Family Singers]] became well-known for their protest songs, especially songs supporting [[abolition]]. They sang at the [[White House]] for President [[John Tyler]], and befriended [[Abraham Lincoln]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/music/protest.html |

|||

| title = UVa Library: Exhibits: Lift Every Voice |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = University of Virginia Library |

|||

}}</ref> Their subject matter most often touched on relevant social issues such as [[abolition]], [[temperance]], [[politics]], [[war]] and women's [[suffrage]]. Much of their music focused on [[idealism]], [[social reform]], [[equal rights]], moral improvement, community activism and [[patriotism]]. |

|||

The Hutchinsons' career spanned the major social and political events of the mid-19thcentury, including the Civil War. The Hutchinson Family Singers established an impressive musical legacy and are considered to be the forerunners of the great protest singers-songwriters and folk groups of the 1950s and 60s such as [[Woody Guthrie]] and [[Bob Dylan]], and are often referred to as America's first protest band.<ref>{{cite web |

The Hutchinsons' career spanned the major social and political events of the mid-19thcentury, including the Civil War. The Hutchinson Family Singers established an impressive musical legacy and are considered to be the forerunners of the great protest singers-songwriters and folk groups of the 1950s and 60s such as [[Woody Guthrie]] and [[Bob Dylan]], and are often referred to as America's first protest band.<ref>{{cite web |

||

| url = http://www.amaranthpublishing.com/hutchinson.htm |

| url = http://www.amaranthpublishing.com/hutchinson.htm |

||

| title = The Hutchinson Family Singers: America's First Protest Singers |

|||

| title = The number of [[lynching]]s accompanying the rise of the [[Ku Klux Klan]] at the turn of the century. In [[1919]], the [[NAACP]] adopted the song as "The Negro National Anthem." By the [[1920s]], copies of "Lift Every Voice and Sing" could be found in black churches across the country, often pasted into the hymnals. |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = Amaranth Publishing |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

A great number of [[Negro spiritual]]s were sung as forms of protest by the enslaved African-American people both before and after the [[American Civil War]].<ref> {{cite web| url= http://ctl.du.edu/spirituals/Freedom/source.cfm| title= Sweet Chariot, the Story of the Spirituals| accessdate= 2007-11-07|Publisher= The University of Denver|}} </ref> They called for freedom from oppression and slavery (as in, for example, "[[Oh, Freedom]]), and employed religious imagery to draw comparisons between their plight and the plight of the downtrodden in the bible (as in "[[Go Down Moses]]"). While these protest songs originated by [[History of slavery in the United States|enslaved African-Americans]] in the [[United States]] when [[Slavery]] was introduced to the [[Europe]]an colonies in [[1619]], it was only after the ratification of the [[Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution]] by [[United States Secretary of State]] [[William Henry Seward]] on [[December 18]], [[1865]] that the songs started to be collected. The two pioneering collections of Black Spirituals and protest songs were the 1872 book ''Jubilee Songs as Sung by the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University'', by Thomas F. Steward, and a collection of "Black spirituals" which was published by [[Thomas Wentworth Higginson]]. The most famous song of protest of African-Americans is "[[Lift Every Voice and Sing]]", often referred to by the title "The Negro National Anthem". The song was originally written as a poem by [[James Weldon Johnson]] ([[1871]]-[[1938]]) and then set to music by his brother [[Rosamond Johnson|John Rosamond Johnson]] ([[1873]]-[[1954]]) in [[1900]] and performed in [[Jacksonville, Florida]] as part of a celebration of [[Abraham Lincoln|Lincoln]]'s Birthday on [[February 12]], [[1900]] by a choir of 500 schoolchildren at the segregated [[Stanton College Preparatory School|Stanton School]], where James Weldon Johnson was principal. Singing this song quickly became a way for [[African American]]s to demonstrate their patriotism and hope for the future. In calling for earth and heaven to "ring with the harmonies of Liberty," they could speak out subtly against [[racism]] and [[Jim Crow laws]] — and especially the huge number of [[lynching]]s accompanying the rise of the [[Ku Klux Klan]] at the turn of the century. In [[1919]], the [[NAACP]] adopted the song as "The Negro National Anthem." By the [[1920s]], copies of "Lift Every Voice and Sing" could be found in black churches across the country, often pasted into the hymnals. |

|||

The 19th century also boasts one of the first [[List of environmental issues|environmental]] protest songs ever written in the shape of "Woodman Spare That Tree!",<ref>{{cite web |

The 19th century also boasts one of the first [[List of environmental issues|environmental]] protest songs ever written in the shape of "Woodman Spare That Tree!",<ref>{{cite web |

||

| Line 10: | Line 50: | ||

| title = Woodman Spare That Tree! |

| title = Woodman Spare That Tree! |

||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

||

| publisher = Amaranth |

| publisher = Amaranth Publishing |

||

}}</ref> which was extremely popular at the time. The words were taken from a poem by [[George Pope Morris]] which had been published in the [[New York Mirror]], while the music was composed by [[Henry Russell]]. The conservation sentiments of the work can be seen in verses such as the 2nd, which reads:" That old familiar tree,/Whose glory and renown/Are spread o'er land and sea/And wouldst thou hack it down?/Woodman, forbear thy stroke!/Cut not its earth, bound ties;/Oh! spare that ag-ed oak/Now towering to the skies!" |

|||

In the [[20th century]], the [[union movement]], the [[Great Depression]], the [[Civil Rights movement]], and the [[Vietnam half of the 20th century was based on the struggle for fair wages and working hours for the working class, and on the attempt to unionize the American workforce towards those ends. The [[Industrial Workers of the World]] (IWW) was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States who were opposed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor. From the start they used music as a powerful form of protest. |

|||

===Twentieth century===<!--2003 Iraq War and 9/11/2001 are not included in the 20th century--> |

|||

One of the most famous of these early 20th century "[[Wobblies]]" was [[Joe Hill]], an IWW activist who traveled widely, organizing workers and writing and singing political songs. He coined the phrase "pie in the sky", which -ravaged America. In [[New York City]], [[Marc Blitzstein]]'s opera/musical "[[The Cradle Will Rock]]", a pro-union musical directed by [[Orson Welles]], was produced in [[1937]]. However, it proved to be so controversial that it was shut down for fear of social unrest.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

In the [[20th century]], the [[union movement]], the [[Great Depression]], the [[Civil Rights movement]], and the [[Vietnam War|war in Vietnam]] (see [[Vietnam War protests]]) all spawned protest songs. |

|||

====1900- 1920; Labor Movement, Class Struggle, and The Great War==== |

|||

[[Image:Joe hill002.jpg|thumb|[[Joe Hill]], one of the pioneering protest singers of the early 20th Century]] |

|||

The vast majority of American protest music from the first half of the 20th century was based on the struggle for fair wages and working hours for the working class, and on the attempt to unionize the American workforce towards those ends. The [[Industrial Workers of the World]] (IWW) was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States who were opposed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor. From the start they used music as a powerful form of protest. |

|||

One of the most famous of these early 20th century "[[Wobblies]]" was [[Joe Hill]], an IWW activist who traveled widely, organizing workers and writing and singing political songs. He coined the phrase "pie in the sky", which appeared in his most famous protest song "[[The Preacher and the Slave]]" (1911). The song calls for "Workingmen of all countries, unite/ Side by side we for freedom will fight/ When the world and its wealth we have gained/ To the grafters we'll sing this refrain." Other notable protest songs written by Hill include "The Tramp", "There Is Power in a Union", "Rebel Girl", and "Casey Jones--Union Scab". |

|||

Another one of the best-known songs of this period was "[[Bread and Roses]]" by [[James Oppenheim]] and [[Caroline Kolsaat]], which was sung in protest en masse at a [[textile]] [[strike]] in [[Lawrence]], [[Massachusetts]] during January-March [[1912]] (now often referred to as the "[[Lawrence textile strike|Bread and Roses strike]]") and has been subsequently taken up by protest movements throughout the 20th century. |

|||

The advent of [[The Great War]] (1914-1918) resulted in a great number of songs concerning the 20th's most popular recipient of protest: war; songs against the war in general, and specifically in America against the U.S.A.'s decision to enter the European war started to become widespread and popular. One of the most successful of these protest songs to capture the widespread American skepticism about joining in the European war was “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” (1915) by lyricist [[Alfred Bryan]] and composer [[Al Piantadosi]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4942/ |

|||

| title = "I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier": Singing Against the War |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-15 |

|||

| publisher = History Matters |

|||

}}</ref>. Many of these war-time protest songs took the point of view of the family at home, worried about their father/husband fighting overseas. One such song of the period which dealt with the children who had been orphaned by the war was "War Babies"(1916) by [[James F. Hanley]] (music) and [[Ballard MacDonald]] (lyrics) which spoke to the need for taking care of orphans of war in an unusually frank and open manner.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://parlorsongs.com/issues/2000-12/2000-12b.asp |

|||

| title = America's Music Goes to War Part 2 B., December 2000 |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-15 |

|||

| publisher = The Parlor Songs Association, Inc. |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

For a typical song written from a child's point-of-view see [[Jean Schwartz]] (music), [[Sam M. Lewis]] & [[Joe Young]] (lyrics) and their song "Hello Central! Give Me No Man's Land"(1918), in which a young boy tries to call his father in [[No Man's Land]] on the [[telephone]] (then a recent invention), unaware that he has been killed in combat.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.firstworldwar.com/audio/hellocentral.htm |

|||

| title = "Hello Central! Give Me No Man's Land" audio |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-15 |

|||

| publisher = Michael Duffy |

|||

}}</ref>. |

|||

====1920s- 1930s;The Great Depression and Racial Discrimination==== |

|||

[[Image:Leadbelly.jpg|thumb|left|[[Leadbelly]], a blues singer who sung of the hardship and racial discrimination faced by African-Americans in America]] |

|||

The 1920s and 30s also saw the continuing growth of the union and labor movements (the IWW claimed at its peak in 1923 some 100,000 members), as well as widespread poverty due to the [[Great Depression]] and the [[Dust Bowl]], which inspired musicians and singers to decry the harsh realities which they saw all around them. It was against this background that folk singer [[Aunt Molly Jackson]] was singing songs with striking [[Harlan]] coal miners in [[Kentucky]] in [[1931]], and writing protest songs such as "Hungry Ragged Blues" and "Poor Miner's Farewell", which depicted the struggle for social justice in a Depression-ravaged America. In [[New York City]], [[Marc Blitzstein]]'s opera/musical "[[The Cradle Will Rock]]", a pro-union musical directed by [[Orson Welles]], was produced in [[1937]]. However, it proved to be so controversial that it was shut down for fear of social unrest.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/strangefruit/depression.html |

| url = http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/strangefruit/depression.html |

||

| title = STRANGE FRUIT. Protest Music - The Great Depression |

| title = STRANGE FRUIT. Protest Music - The Great Depression |

||

| Line 20: | Line 93: | ||

}}</ref> Undeterred, the IWW increasingly used music to protest working conditions in the United States and to recruit new members to their cause. |

}}</ref> Undeterred, the IWW increasingly used music to protest working conditions in the United States and to recruit new members to their cause. |

||

The 1920s and 30s also saw a marked rise in the number of songs which protested against racial discrimination, such as [[Louis Armstrong]]'s "(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue" (1929), and the anti-lynching song, "[[Strange Fruit]]" by [[Lewis Allan]] (which contains the lyrics "Southern trees bear |

The 1920s and 30s also saw a marked rise in the number of songs which protested against racial discrimination, such as [[Louis Armstrong]]'s "(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue" (1929), and the anti-lynching song, "[[Strange Fruit]]" by [[Lewis Allan]] (which contains the lyrics "Southern trees bear strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze"). It was also during this period that many [[African American]] blues singers were beginning to have their voices heard on a larger scale across America through their music, most of which protested the discrimination which they faced on a daily basis. Perhaps the most famous example of these 1930s blues protest songs is [[Leadbelly]]'s [[The Bourgeois Blues]], in which he sings "The home of the Brave / The land of the Free / I don't wanna be mistreated by no bourgeoisie". |

||

====1940s- 1950s; The labor movement vs McCarthyism; Anti-Nuclear songs==== |

|||

[[Image:Woody Guthrie.jpg|thumb|1940s protest singer Woody Guthrie]] |

|||

[[Image:JoshWhite1945.jpg|thumb|[[Josh White]], the leading proponent or political blues and anti-segregation songs among 1940s African American artists]] |

|||

The 1940s and 1950s saw the rise of music that continued to protest labor, race, and class issues. Protest songs continued to increase their profile over this period, and an increasing number of artists appeared who were to have an enduring influence on the protest music genre. However, the movement and its protest singers faced increasing opposition from [[McCarthyism]]. One of the most notable pro-union protest singers of the period was [[Woody Guthrie]] ("[[This Land Is Your Land]]", "[[Deportee]]", "Dust Bowl Blues", "Tom Joad"), whose guitar bore a sticker which read: "This Machine Kills Fascists". Guthrie had also been a member or the hugely influential labor-movement band [[The Almanac Singers]], along with [[Millard Lampell]], [[Lee Hays]], and [[Pete Seeger]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.peteseeger.net/new_yorker041706.htm |

|||

| title = THE PROTEST SINGER: Pete Seeger and American folk music. |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-15 |

|||

| publisher = The New Yorker |

|||

}}</ref> Politics and music were closely intertwined with the members' political beliefs, which were far-left and occasionally led to controversial associations with the Communist Party USA. Their first release, an album called ''[[Songs For John Doe]]'',<ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.geocities.com/Nashville/3448/doe.html | title= Songs for John Doe (The Almanac Singers) (1941)}}</ref> urged non-intervention in World War II. In fact, an article written in 2006 by an official of the American libertarian [[Cato Institute]] reported that in the early years of World War II, political opponents had referred to Seeger as "[[Stalin]]'s Songbird".<ref>David Boaz, [http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/david_boaz/2006/04/post_33.html Stalin's songbird], Comment is free, ''Guardian'' Unlimited. April 14, 2006. Accessed online 16 October 2007.</ref> Their second album "Talking Union", was a collection of labor songs, many of which were intensely anti-Roosevelt owing to what Seeger considered the President's weak support of workers' rights. |

|||

A similarly influential folk music band who sang protest songs were [[The Weavers]], of which future protest music leader [[Pete Seeger]] was a member. [[The Weavers]] were the first American band to court mainstream success while singing protest songs, and they were eventually to pay the price for it. While they specifically avoided recording the more controversial songs in their repertoire, and refrained from performing at controversial venues and events (for which the leftwing press derided them as having sold out their beliefs in exchange for popular success), they nevertheless came under political pressure as a result of their history of singing protest songs and folk songs favoring labor unions, as well as for the leftist political beliefs of the individuals in the group. Despite their caution they were placed under [[FBI]] surveillance and blacklisted by parts of the entertainment industry during the McCarthy era, from 1950. Right-wing and anti-Communist groups protested at their performances and harassed promoters. As a result of the blacklisting, the Weavers lost radio airplay and the group's popularity diminished rapidly. [[Decca Records]] eventually terminated their recording contract. |

|||

In the 1940s the strongest musical voice of protest from the African American community in America was [[Josh White]], one of the first musicians to make a name for himself singing political blues. <ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.elijahwald.com/joshprotest.html | title= Josh White and the Protest Blues | publisher= elijahwald.com}} </ref>. White enjoyed a position of political privilege, especially as a black musician, as he established a long and close relationship with the family of [[Franklin Roosevelt|Franklin]] and [[Eleanor Roosevelt]], and would become the closest African American confidant to the [[President of the United States]]. He made his first foray into protest music and political blues with his highly controversial [[Columbia Records]] album ''Joshua White & His Carolinians: Chain Gang'', produced by [[John H. Hammond]], which included the song "Trouble," which summarised the plight of many African Americans in its opening line of "Well, I always been in trouble, ‘cause I’m a black-skinned man." The album was the first race record ever forced upon the white radio stations and record stores in America's South and caused such a furor that it reached the desk of President Franklin Roosevelt. On [[December 20]], [[1940]], White and the [[Golden Gate Quartet]], sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt, performed in a historic [[Washington, D.C.]] concert at the Library of Congress's Coolidge Auditorium to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the [[Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States]], which abolished slavery. In January 1941, Josh performed at the President's Inauguration, and two months later he released another highly controversial record album, ''Southern Exposure'', which included six anti-segregationist songs with liner notes written by the celebrated and equally controversial African American writer [[Richard Wright]], and whose sub-title was "An Album of Jim Crow Blues". Like the ''Chain Gang'' album, and with revelatory yet inflammatory songs such as "Uncle Sam Says", "Jim Crown Train", "Bad Housing Blues", Defense Factory Blues", "Southern Exposure", and "Hard Time Blues", it also was forced upon the southern white radio stations and record stores, caused outrage in the South and also was brought to the attention of President Roosevelt. However, instead of making White persona-non-grata in segregated America, it resulted in President Roosevelt asking White to become the first African American artist to give a [[White House]] Command Performance, in 1941. |

|||

After the [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] on August 6th and 9th 1945, many people the world over feared [[Nuclear warfare]], and many protest songs were written against this new danger to planet. The most immediately successful of these post-war anti-nuclear protest songs was Vern Partlow's "Old Man Atom" (1945) (also known by the alternate titles "Atomic Talking Blues" and "Talking Atom"). The song treats its subject in comic-serious fashion, with a combination of black humour puns (such as "We hold these truths to be self-evident/All men may be cremated equal" or "I don't mean the Adam that Mother Eve mated/I mean that thing that science liberated") on serious statements on the choices to be made in the nuclear age ("The people of the world must pick out a thesis/"Peace in the world, or the world in pieces!""). Folk singer [[Sam Hinton]] recorded "Old Man Atom" in 1950 for ABC Eagle, a small California independent label. Influential New York disc jockey [[Martin Block]] played Hinton's record on his 'Make Believe Ballroom.' Overwhelming listener response prompted [[Columbia Records]] to acquire the rights for national distribution. From all indications, it promised to be one of the year's biggest novelty records. RCA Victor rush-released a cover version by the [[Sons of the Pioneers]]. Country singer Ozzie Waters recorded the song for Decca's Coral subsidiary. Fred Hellerman - then contracted to Decca as a member of the Weavers - recorded it for Jubilee under the pseudonym 'Bob Hill.' [[Bing Crosby]] was reportedly ready to record "Old Man Atom" for Decca when right-wing organizations began attacking Columbia and RCA Victor for releasing a song that reflected a Communist ideology. According to a New York Times report on September 1, 1950. <blockquote>Those who protested against the song's issuance on records insisted that it parroted the Communist line on peace and reflected the propaganda for the Stockholm 'peace petition.' Mr. Partlow said yesterday, according to an Associated Press dispatch from Los Angeles, that his song was 'not part of the Stockholm or any other so-called peace offensive.' He added, 'It was written five years ago long before any of these peace offensives.'<ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.fortunecity.com/tinpan/parton/2/atom.html | title= "Old Man Atom" | publisher= Fortune City}} </ref> </blockquote> Buckling under pressure, both Columbia and RCA Victor withdrew "Old Man Atom" from distribution. |

|||

Other anti-nuclear protest songs of the period include "Atom and Evil" (1946) by [[Golden Gate Quartet]] ("if Atom and Evil should ever be wed/Lord, then darn if all of us are going to be dead") <ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.authentichistory.com/1950s/atomicmusic/1946_Atom_And_Evil-Golden_Gate_Quartet.html | title= "Atom and Evil" lyrics | publisher= The Authentic History Center}}</ref> and "Atomic Sermon" (1953) by Billy Hughes and his Rhythm Buckeroos <ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.atomicplatters.com/more.php?id=113_0_1_0_M | title= "Atomic Sermon" | publisher= conelrad.com}}</ref> |

|||

====1960s; the Civil Rights Movement, The Vietnam War, and Peace and Revolution==== |

|||

[[Image:1963 march on washington.jpg|thumb|right|Civil Rights March on [[Washington, D.C.|Washington]], leaders marching from the [[Washington Monument]] to the [[Lincoln Memorial]], [[August 28]], [[1963]].]] |

|||

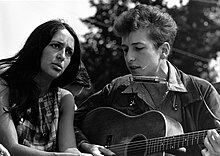

[[Image:Joan Baez Bob Dylan.jpg|thumb|Bob Dylan with [[Joan Baez]] during the Civil Rights March in [[Washington, D.C.]], 1963]] |

|||

The 1960s was a fertile era for the genre, especially with the rise of the [[Civil Rights movement]], the ascendency of [[counterculture]] groups such as [[Hippies]] and the [[New Left]], and the escalation of the [[Vietnam War|War in Vietnam]]. The protest songs of the period differed from those of earlier leftist movements; which had been more oriented towards labour activism; adopting instead a broader definition of political activism commonly called [[social activism]], which incorporated notions of equal rights and of promoting the concept of 'peace'. The music often included relatively simple instrumental accompaniment including acoustic [[guitar]] and [[harmonica]]. |

|||

One of the key figures of the 1960s protest movement was [[Bob Dylan]], who produced a number of landmark protest songs such as "[[Blowin' in the Wind]]" (1962), "[[Masters of War]]" (1963), "[[Talking World War III Blues]]" (1963), and "[[The Times They Are A-Changin']]" (1964). While Dylan is often thought of as a 'protest singer', most of his protest songs spring from a relatively short time-period in his career; Mike Marqusee writes: <blockquote>The protest songs that made Dylan famous and with which he continues to be associated were written in a brief period of some 20 months – from January 1962 to November 1963. Influenced by American radical traditions (the Wobblies, the Popular Front of the thirties and forties, the Beat anarchists of the fifties) and above all by the political ferment touched off among young people by the civil rights and ban the bomb movements, he engaged in his songs with the terror of the nuclear arms race, with poverty, racism and prison, jingoism and war.<ref name=dylanpolitics> {{cite web | url= http://www.redpepper.org.uk/article561.html | title= The Politics of Bob Dylan | accessdate= 2007-01-09 | publisher= Red Pepper}} </ref> </blockquote> Dylan often sang against injustice, such as the murder of [[African American]] [[African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|civil rights]] [[activism|activist]] [[Medgar Evers]] in ‘[[Only A Pawn In their Game]]’ (1964), or the killing of the 51-year-old African American barmaid Hattie Carroll by the wealthy young tobacco farmer from Charles County, William Devereux "Billy" Zantzinger in '[[The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll]]" (1964) (Zantzinger was only sentenced to six months in a county jail for the murder). Many of the injustices about which Dylan sang were not even based on race or civil rights issues, but rather everyday injustices and tragedies, such as the death of boxer [[Davey Moore]] in the ring ("Who Killed Davey Moore?" (1964)<ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/daveymoore.html | title= "Who Killed Davey Moore?" lyrics | accessdate= 2007-01-19 | publisher= bobdylan.com}}</ref> ), or the breakdown of farming and mining communities ("Ballad of Hollis Brown" (1963), "[[North Country Blues]]" (1963)). By 1963, Dylan and then-singing partner [[Joan Baez]] had become prominent in the [[civil rights]] movement, singing together at rallies including the [[March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom|March on Washington]] where [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] delivered his famous "[[I have a dream]]" speech.<ref>Dylan performed [[Only a Pawn in Their Game]] and [[When the Ship Comes In]]</ref>, however Dylan is reported to have said: "“Think they’re listening?” Dylan asked, glancing towards the Capitol. “No, they ain’t listening at all.” <ref> Scaduto, ''Bob Dylan'', p. 151 </ref> Many of Dylan's songs of the period were to be adapted and appropriated by the 60s Civil Rights and counter-culture 'movements' rather than being specifically written for them, and by 1964 Dylan was attempting to extract himself from the movement, much to the chagrin of many of those who saw him as a voice of a generation. Indeed, many of Dylan's songs have been retrospectively aligned with issues which they in fact pre-date; while "[[Masters of War]]" (1963) clearly protests against governments who orchestrate war, it is often misconstrued as dealing directly with the [[Vietnam War]]. However the song was written at the beginning of 1963, when only a few hundred Green Berets were stationed in South Vietnam. The song only came to be re-appropriated as a comment on Vietnam in 1965, when US planes bombed North Vietnam for the first time, with lines such as “you that build the death planes” seeming particularly prophetic (in fact, unlike many of his contemporary 'protest singers', Dylan never mentioned Vietnam by name in any of his songs). Dylan is quoted as saying that the song "is supposed to be a pacifistic song against war. It's not an anti-war song. It's speaking against what [[Dwight D. Eisenhower|Eisenhower]] was calling a [[military-industrial complex]] as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up."<ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/2001-09-10-bob-dylan.htm#more | title= Dylan is positively on top of his game | accessdate= 2007-01-19 | publisher= USA Today}}</ref> Similarly ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ (1963) is often perceived to deal with the [[Cuban missile crisis]], however Dylan performed the song more than a month before [[John F. Kennedy]]'s TV address to the nation (October 22, 1962) initiated the Cuban missile crisis. After this brief, but extremely fruitful, 20 month period of 'protest songs', Dylan decided to extract himself from the movement, changing his musical style from folk to a more rock-orientated sound, and writing increasingly abstract lyrics, which had more in common with poetry and biblical references than social injustices. As he explained to critic Nat Hentoff in mid-1964: “Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore - you know, be a spokesman. From now on, I want to write from inside me …I’m not part of no movement… I just can’t make it with any organisation…”.<ref name=dylanpolitics/> His next acknowledged 'protest song' would be "[[Hurricane (song)|The Hurricane]]", written twelve years later in 1976. |

|||

[[Pete Seeger]], formerly of [[The Almanacs]] and [[The Weavers]] and a major influence on Dylan and his contemporaries, continued to be a strong voice of protest in the 1960s, when he produced "[[Where Have All the Flowers Gone]]", and "[[Turn, Turn, Turn]]" (written during the 1950s but released on Seeger's 1962 album ''The Bitter and The Sweet''). Seeger's song "[[If I Had a Hammer]]" had been written in 1949 in support of the [[Progressivism|progressive movement]], but rose to Top Ten popularity in 1962 when covered by [[Peter, Paul and Mary]]), going on to become one of the major [[Civil Rights anthem]]s of the [[American Civil Rights movement]]. "[[We Shall Overcome]]", Seeger's adaptation of an American gospel song, continues to be used to support issues from labor rights to peace movements. Seeger was one of the leading singers to protest against then-[[President of the United States|President]] [[Lyndon Johnson]] through song. Seeger first [[satire|satirically]] attacked the president with his 1966 recording of [[Len Chandler]]'s children's song, "Beans in My Ears". In addition to Chandler's original lyrics, Seeger sang that "Mrs. Jay's little son Alby" had "beans in his ears", which, as the lyrics imply,<ref> {{cite web | url= http://sniff.numachi.com/pages/tiBEANEARS.html | title= Beans in My Ears lyrics}} </ref> ensures that a person does not hear what is said to them. To those opposed to continuing the [[Vietnam War]] the phrase suggested that "Alby Jay", a loose pronunciation of Johnson's nickname "LBJ", did not listen to anti-war protests as he too had "beans in his ears". Seeger attracted wider attention in 1967 with his song "[[Waist Deep in the Big Muddy]]", about a [[Captain#Military and Air Force|captain]] — referred to in the lyrics as "the big fool" — who drowned while leading a platoon on maneuvers in [[Louisiana]] during [[World War II]]. In the face of arguments with the management of [[CBS]] about whether the song's political weight was in keeping with the usually light-hearted entertainment of the ''[[Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour]]'', the final lines were "Every time I read the paper/those old feelings come on/We are waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on." And it was not seriously contested{{Fact|date=December 2007}} that much of the audience would grasp Seeger's allegorical casting of Johnson as the "big fool" and the [[Vietnam War]] the foreseeable danger. Although the performance was cut from the September 1967 show, after wide publicity,<ref>{{cite web | url= http://www.peteseeger.net/givepeacechance.htm | title= How "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy" Finally Got on Network Television in 1968 | pubisher= peteseeger.net}}</ref> it was broadcast when Seeger appeared again on the Smothers' Brothers show in the following January. |

|||

[[Phil Ochs]], one of the leading protest singers of the decade (or, as he preferred, a "[[topical song|topical singer]]"), performed at many political events, including [[Opposition to the Vietnam War|anti-Vietnam War]] and [[American civil rights movement|civil rights]] rallies, student events, and organized labor events over the course of his career, in addition to many concert appearances at such venues as New York City's [[The Town Hall]] and [[Carnegie Hall]]. Politically, Ochs described himself as a "left social democrat" who turned into an "early revolutionary" after the [[1968 Democratic National Convention]] in Chicago, which had a profound effect on his state of mind.<ref>Schumacher (1996), p. 201</ref> Ochs summarised protest songs thus: "A protest song is a song that's so specific that you cannot mistake it for bullshit" <ref> {{cite web | url= http://www.people.ubr.com/artists/by-first-name/p/phil-ochs/phil-ochs-quotes/a-protest-song-is-a.aspx | title= 'Phil Ochs' Quote | publisher= UBR, Inc.}} </ref> Some of his best known protest songs include "Power and the Glory", "Draft Dodger Rag", "There But for Fortune", "Changes", "Crucifixion, "When I'm Gone", "Love Me I'm a Liberal", "Links on the Chain", "Ringing of Revolution", and "I Ain't Marching Anymore".Other notable voices of protest from the period included [[Joan Baez]], , [[Buffy Sainte-Marie]] (whose anti-war song "[[Universal Soldier (song)|Universal Soldier]]" was later made famous by [[Donovan]]) and [[Tom Paxton]] ("Jimmy Newman" - about the story of a dying soldier, and "My Son John" - about a soldier who returns from war unable to describe what he's been through), among others. The first protest song to reach number one in the United States was [[Eve of Destruction (song)|Eve of Destruction]] by [[Barry McGuire]] in 1965.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.ischool.berkeley.edu/~nunberg/protest.html |

|||

| title = Geoffrey Nunberg - the history of "protest" |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-03 |

|||

| publisher = Geoffrey Nunberg |

|||

}}</ref>. |

|||

The [[American civil rights movement]] of the 1950s and 1960s often used [[Negro spirituals]] as a source of protest, changing the religious lyrics to suit the political mood of the time. The use of religious music helped to emphasize the peaceful nature of the protest; it also proved easy to adapt, with many improvised [[call-and-response]] songs being created during marches and sit-ins. Some imprisoned protesters used their incarceration as an opportunity to write protest songs. These songs were carried across the country by [[Freedom rides|Freedom Riders]],<ref>{{cite web |

The [[American civil rights movement]] of the 1950s and 1960s often used [[Negro spirituals]] as a source of protest, changing the religious lyrics to suit the political mood of the time. The use of religious music helped to emphasize the peaceful nature of the protest; it also proved easy to adapt, with many improvised [[call-and-response]] songs being created during marches and sit-ins. Some imprisoned protesters used their incarceration as an opportunity to write protest songs. These songs were carried across the country by [[Freedom rides|Freedom Riders]],<ref>{{cite web |

||

Revision as of 17:15, 26 March 2008

Template:Globalize/USA A protest song is a song which protests perceived problems in society and with world conflicts. Every major movement in Western history has been accompanied by its own collection of protest songs, from slave emancipation to women's suffrage, the labor movement, civil rights, the anti-war movement, the feminist movement, the environmental movement. Over time, the songs have come to protest more abstract, moral issues, such as injustice, racial discrimination, the morality of war in general (as opposed to purely protesting individual wars), globalization, inflation, social inequalities, and incarceration. Such songs generally become more popular during times of social disruption among social groups. The oldest European protest song on record is "The Cutty Wren" from the English peasants' revolt of 1381 against feudal oppression.[1]

Some of the most internationally famous examples of protest songs come from the U.S. They include "We Shall Overcome" (a song popular in the labor movement and later the Civil Rights movement), Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind and Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On". Many key figures world-wide have contributed to their own nations' traditions of protest music, such as Victor Jara in Latin America, Silvio Rodríguez in Cuba and Vuyisile Mini in anti-apartheid South Africa. Protest songs are generally associated with folk music, but more recently they have been produced in all genres of music.

North American songs of protest

Eighteenth century

Prior to the American Revolutionary War, political songs appeared in the mid 1700s America in response to social injustices (such as the struggle between classes) and political issues (such as the opposing ideologies of the Whigs and Tories, and issues such as the stamp act). "American Taxation" written by Peter St. John and sung to the tune of "The British Grenadiers" was one such song which protested against "the cruel lords of Britain" who were "striving after our rights to take away, and rob us of our charter, in North America".[2] "Come On, Brave Boys" (1734), "The American Hero" by Andrew Law, "Free America" by Dr. Joseph Warren, and "Liberty Song" by John Dickinson (1768) all equally protested against the British rule in America, and called for freedom.[3] The earliest known American election campaign song was "God Save George Washington", issued in 1780 and sung to the tune of "God Save the King", a common practice as the majority of political songs at the time were based on already well known music and were often published with only the lyrics in newspapers and broadsides, and a "sung to the tune of" direction.[4]

"Rights of Woman" (1795), sung to the tune of "God Save the King", written anonymously by "A Lady", and published in the Philadelphia Minerva, October 17, 1795, is one of the earliest American songs pointing out that rights apply equally to both sexes.[3] The song contains many outspoken declarations of protest, and slogans such as "God save each Female's right", "Woman is free" and "Let woman have a share".

Nineteenth century

The nineteenth century saw a number of protest songs being written, for the most part, on three key issues: War, and the American Civil War in particular (such as "Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye" from Ireland, and its American variant, "When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again", among others); The abolition of slavery ("Song of the Abolitionist"[5] and "No More Auction Block for Me",[6] among others) and Women's suffrage, both for and against in both Britain and the U.S.

Perhaps the most famous voices of protest at the time - in America at least - were the Hutchinson Family Singers. From 1839, the Hutchinson Family Singers became well-known for their protest songs, especially songs supporting abolition. They sang at the White House for President John Tyler, and befriended Abraham Lincoln.[7] Their subject matter most often touched on relevant social issues such as abolition, temperance, politics, war and women's suffrage. Much of their music focused on idealism, social reform, equal rights, moral improvement, community activism and patriotism.

The Hutchinsons' career spanned the major social and political events of the mid-19thcentury, including the Civil War. The Hutchinson Family Singers established an impressive musical legacy and are considered to be the forerunners of the great protest singers-songwriters and folk groups of the 1950s and 60s such as Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, and are often referred to as America's first protest band.[8]

A great number of Negro spirituals were sung as forms of protest by the enslaved African-American people both before and after the American Civil War.[9] They called for freedom from oppression and slavery (as in, for example, "Oh, Freedom), and employed religious imagery to draw comparisons between their plight and the plight of the downtrodden in the bible (as in "Go Down Moses"). While these protest songs originated by enslaved African-Americans in the United States when Slavery was introduced to the European colonies in 1619, it was only after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution by United States Secretary of State William Henry Seward on December 18, 1865 that the songs started to be collected. The two pioneering collections of Black Spirituals and protest songs were the 1872 book Jubilee Songs as Sung by the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, by Thomas F. Steward, and a collection of "Black spirituals" which was published by Thomas Wentworth Higginson. The most famous song of protest of African-Americans is "Lift Every Voice and Sing", often referred to by the title "The Negro National Anthem". The song was originally written as a poem by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) and then set to music by his brother John Rosamond Johnson (1873-1954) in 1900 and performed in Jacksonville, Florida as part of a celebration of Lincoln's Birthday on February 12, 1900 by a choir of 500 schoolchildren at the segregated Stanton School, where James Weldon Johnson was principal. Singing this song quickly became a way for African Americans to demonstrate their patriotism and hope for the future. In calling for earth and heaven to "ring with the harmonies of Liberty," they could speak out subtly against racism and Jim Crow laws — and especially the huge number of lynchings accompanying the rise of the Ku Klux Klan at the turn of the century. In 1919, the NAACP adopted the song as "The Negro National Anthem." By the 1920s, copies of "Lift Every Voice and Sing" could be found in black churches across the country, often pasted into the hymnals.

The 19th century also boasts one of the first environmental protest songs ever written in the shape of "Woodman Spare That Tree!",[10] which was extremely popular at the time. The words were taken from a poem by George Pope Morris which had been published in the New York Mirror, while the music was composed by Henry Russell. The conservation sentiments of the work can be seen in verses such as the 2nd, which reads:" That old familiar tree,/Whose glory and renown/Are spread o'er land and sea/And wouldst thou hack it down?/Woodman, forbear thy stroke!/Cut not its earth, bound ties;/Oh! spare that ag-ed oak/Now towering to the skies!"

Twentieth century

In the 20th century, the union movement, the Great Depression, the Civil Rights movement, and the war in Vietnam (see Vietnam War protests) all spawned protest songs.

1900- 1920; Labor Movement, Class Struggle, and The Great War

The vast majority of American protest music from the first half of the 20th century was based on the struggle for fair wages and working hours for the working class, and on the attempt to unionize the American workforce towards those ends. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States who were opposed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor. From the start they used music as a powerful form of protest.

One of the most famous of these early 20th century "Wobblies" was Joe Hill, an IWW activist who traveled widely, organizing workers and writing and singing political songs. He coined the phrase "pie in the sky", which appeared in his most famous protest song "The Preacher and the Slave" (1911). The song calls for "Workingmen of all countries, unite/ Side by side we for freedom will fight/ When the world and its wealth we have gained/ To the grafters we'll sing this refrain." Other notable protest songs written by Hill include "The Tramp", "There Is Power in a Union", "Rebel Girl", and "Casey Jones--Union Scab".

Another one of the best-known songs of this period was "Bread and Roses" by James Oppenheim and Caroline Kolsaat, which was sung in protest en masse at a textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts during January-March 1912 (now often referred to as the "Bread and Roses strike") and has been subsequently taken up by protest movements throughout the 20th century.

The advent of The Great War (1914-1918) resulted in a great number of songs concerning the 20th's most popular recipient of protest: war; songs against the war in general, and specifically in America against the U.S.A.'s decision to enter the European war started to become widespread and popular. One of the most successful of these protest songs to capture the widespread American skepticism about joining in the European war was “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” (1915) by lyricist Alfred Bryan and composer Al Piantadosi.[11]. Many of these war-time protest songs took the point of view of the family at home, worried about their father/husband fighting overseas. One such song of the period which dealt with the children who had been orphaned by the war was "War Babies"(1916) by James F. Hanley (music) and Ballard MacDonald (lyrics) which spoke to the need for taking care of orphans of war in an unusually frank and open manner.[12] For a typical song written from a child's point-of-view see Jean Schwartz (music), Sam M. Lewis & Joe Young (lyrics) and their song "Hello Central! Give Me No Man's Land"(1918), in which a young boy tries to call his father in No Man's Land on the telephone (then a recent invention), unaware that he has been killed in combat.[13].

1920s- 1930s;The Great Depression and Racial Discrimination

The 1920s and 30s also saw the continuing growth of the union and labor movements (the IWW claimed at its peak in 1923 some 100,000 members), as well as widespread poverty due to the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, which inspired musicians and singers to decry the harsh realities which they saw all around them. It was against this background that folk singer Aunt Molly Jackson was singing songs with striking Harlan coal miners in Kentucky in 1931, and writing protest songs such as "Hungry Ragged Blues" and "Poor Miner's Farewell", which depicted the struggle for social justice in a Depression-ravaged America. In New York City, Marc Blitzstein's opera/musical "The Cradle Will Rock", a pro-union musical directed by Orson Welles, was produced in 1937. However, it proved to be so controversial that it was shut down for fear of social unrest.[14] Undeterred, the IWW increasingly used music to protest working conditions in the United States and to recruit new members to their cause.

The 1920s and 30s also saw a marked rise in the number of songs which protested against racial discrimination, such as Louis Armstrong's "(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue" (1929), and the anti-lynching song, "Strange Fruit" by Lewis Allan (which contains the lyrics "Southern trees bear strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze"). It was also during this period that many African American blues singers were beginning to have their voices heard on a larger scale across America through their music, most of which protested the discrimination which they faced on a daily basis. Perhaps the most famous example of these 1930s blues protest songs is Leadbelly's The Bourgeois Blues, in which he sings "The home of the Brave / The land of the Free / I don't wanna be mistreated by no bourgeoisie".

1940s- 1950s; The labor movement vs McCarthyism; Anti-Nuclear songs

The 1940s and 1950s saw the rise of music that continued to protest labor, race, and class issues. Protest songs continued to increase their profile over this period, and an increasing number of artists appeared who were to have an enduring influence on the protest music genre. However, the movement and its protest singers faced increasing opposition from McCarthyism. One of the most notable pro-union protest singers of the period was Woody Guthrie ("This Land Is Your Land", "Deportee", "Dust Bowl Blues", "Tom Joad"), whose guitar bore a sticker which read: "This Machine Kills Fascists". Guthrie had also been a member or the hugely influential labor-movement band The Almanac Singers, along with Millard Lampell, Lee Hays, and Pete Seeger.[15] Politics and music were closely intertwined with the members' political beliefs, which were far-left and occasionally led to controversial associations with the Communist Party USA. Their first release, an album called Songs For John Doe,[16] urged non-intervention in World War II. In fact, an article written in 2006 by an official of the American libertarian Cato Institute reported that in the early years of World War II, political opponents had referred to Seeger as "Stalin's Songbird".[17] Their second album "Talking Union", was a collection of labor songs, many of which were intensely anti-Roosevelt owing to what Seeger considered the President's weak support of workers' rights.

A similarly influential folk music band who sang protest songs were The Weavers, of which future protest music leader Pete Seeger was a member. The Weavers were the first American band to court mainstream success while singing protest songs, and they were eventually to pay the price for it. While they specifically avoided recording the more controversial songs in their repertoire, and refrained from performing at controversial venues and events (for which the leftwing press derided them as having sold out their beliefs in exchange for popular success), they nevertheless came under political pressure as a result of their history of singing protest songs and folk songs favoring labor unions, as well as for the leftist political beliefs of the individuals in the group. Despite their caution they were placed under FBI surveillance and blacklisted by parts of the entertainment industry during the McCarthy era, from 1950. Right-wing and anti-Communist groups protested at their performances and harassed promoters. As a result of the blacklisting, the Weavers lost radio airplay and the group's popularity diminished rapidly. Decca Records eventually terminated their recording contract.

In the 1940s the strongest musical voice of protest from the African American community in America was Josh White, one of the first musicians to make a name for himself singing political blues. [18]. White enjoyed a position of political privilege, especially as a black musician, as he established a long and close relationship with the family of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and would become the closest African American confidant to the President of the United States. He made his first foray into protest music and political blues with his highly controversial Columbia Records album Joshua White & His Carolinians: Chain Gang, produced by John H. Hammond, which included the song "Trouble," which summarised the plight of many African Americans in its opening line of "Well, I always been in trouble, ‘cause I’m a black-skinned man." The album was the first race record ever forced upon the white radio stations and record stores in America's South and caused such a furor that it reached the desk of President Franklin Roosevelt. On December 20, 1940, White and the Golden Gate Quartet, sponsored by Eleanor Roosevelt, performed in a historic Washington, D.C. concert at the Library of Congress's Coolidge Auditorium to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which abolished slavery. In January 1941, Josh performed at the President's Inauguration, and two months later he released another highly controversial record album, Southern Exposure, which included six anti-segregationist songs with liner notes written by the celebrated and equally controversial African American writer Richard Wright, and whose sub-title was "An Album of Jim Crow Blues". Like the Chain Gang album, and with revelatory yet inflammatory songs such as "Uncle Sam Says", "Jim Crown Train", "Bad Housing Blues", Defense Factory Blues", "Southern Exposure", and "Hard Time Blues", it also was forced upon the southern white radio stations and record stores, caused outrage in the South and also was brought to the attention of President Roosevelt. However, instead of making White persona-non-grata in segregated America, it resulted in President Roosevelt asking White to become the first African American artist to give a White House Command Performance, in 1941.

After the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th 1945, many people the world over feared Nuclear warfare, and many protest songs were written against this new danger to planet. The most immediately successful of these post-war anti-nuclear protest songs was Vern Partlow's "Old Man Atom" (1945) (also known by the alternate titles "Atomic Talking Blues" and "Talking Atom"). The song treats its subject in comic-serious fashion, with a combination of black humour puns (such as "We hold these truths to be self-evident/All men may be cremated equal" or "I don't mean the Adam that Mother Eve mated/I mean that thing that science liberated") on serious statements on the choices to be made in the nuclear age ("The people of the world must pick out a thesis/"Peace in the world, or the world in pieces!""). Folk singer Sam Hinton recorded "Old Man Atom" in 1950 for ABC Eagle, a small California independent label. Influential New York disc jockey Martin Block played Hinton's record on his 'Make Believe Ballroom.' Overwhelming listener response prompted Columbia Records to acquire the rights for national distribution. From all indications, it promised to be one of the year's biggest novelty records. RCA Victor rush-released a cover version by the Sons of the Pioneers. Country singer Ozzie Waters recorded the song for Decca's Coral subsidiary. Fred Hellerman - then contracted to Decca as a member of the Weavers - recorded it for Jubilee under the pseudonym 'Bob Hill.' Bing Crosby was reportedly ready to record "Old Man Atom" for Decca when right-wing organizations began attacking Columbia and RCA Victor for releasing a song that reflected a Communist ideology. According to a New York Times report on September 1, 1950.

Those who protested against the song's issuance on records insisted that it parroted the Communist line on peace and reflected the propaganda for the Stockholm 'peace petition.' Mr. Partlow said yesterday, according to an Associated Press dispatch from Los Angeles, that his song was 'not part of the Stockholm or any other so-called peace offensive.' He added, 'It was written five years ago long before any of these peace offensives.'[19]

Buckling under pressure, both Columbia and RCA Victor withdrew "Old Man Atom" from distribution.

Other anti-nuclear protest songs of the period include "Atom and Evil" (1946) by Golden Gate Quartet ("if Atom and Evil should ever be wed/Lord, then darn if all of us are going to be dead") [20] and "Atomic Sermon" (1953) by Billy Hughes and his Rhythm Buckeroos [21]

1960s; the Civil Rights Movement, The Vietnam War, and Peace and Revolution

The 1960s was a fertile era for the genre, especially with the rise of the Civil Rights movement, the ascendency of counterculture groups such as Hippies and the New Left, and the escalation of the War in Vietnam. The protest songs of the period differed from those of earlier leftist movements; which had been more oriented towards labour activism; adopting instead a broader definition of political activism commonly called social activism, which incorporated notions of equal rights and of promoting the concept of 'peace'. The music often included relatively simple instrumental accompaniment including acoustic guitar and harmonica.

One of the key figures of the 1960s protest movement was Bob Dylan, who produced a number of landmark protest songs such as "Blowin' in the Wind" (1962), "Masters of War" (1963), "Talking World War III Blues" (1963), and "The Times They Are A-Changin'" (1964). While Dylan is often thought of as a 'protest singer', most of his protest songs spring from a relatively short time-period in his career; Mike Marqusee writes:

The protest songs that made Dylan famous and with which he continues to be associated were written in a brief period of some 20 months – from January 1962 to November 1963. Influenced by American radical traditions (the Wobblies, the Popular Front of the thirties and forties, the Beat anarchists of the fifties) and above all by the political ferment touched off among young people by the civil rights and ban the bomb movements, he engaged in his songs with the terror of the nuclear arms race, with poverty, racism and prison, jingoism and war.[22]

Dylan often sang against injustice, such as the murder of African American civil rights activist Medgar Evers in ‘Only A Pawn In their Game’ (1964), or the killing of the 51-year-old African American barmaid Hattie Carroll by the wealthy young tobacco farmer from Charles County, William Devereux "Billy" Zantzinger in 'The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" (1964) (Zantzinger was only sentenced to six months in a county jail for the murder). Many of the injustices about which Dylan sang were not even based on race or civil rights issues, but rather everyday injustices and tragedies, such as the death of boxer Davey Moore in the ring ("Who Killed Davey Moore?" (1964)[23] ), or the breakdown of farming and mining communities ("Ballad of Hollis Brown" (1963), "North Country Blues" (1963)). By 1963, Dylan and then-singing partner Joan Baez had become prominent in the civil rights movement, singing together at rallies including the March on Washington where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I have a dream" speech.[24], however Dylan is reported to have said: "“Think they’re listening?” Dylan asked, glancing towards the Capitol. “No, they ain’t listening at all.” [25] Many of Dylan's songs of the period were to be adapted and appropriated by the 60s Civil Rights and counter-culture 'movements' rather than being specifically written for them, and by 1964 Dylan was attempting to extract himself from the movement, much to the chagrin of many of those who saw him as a voice of a generation. Indeed, many of Dylan's songs have been retrospectively aligned with issues which they in fact pre-date; while "Masters of War" (1963) clearly protests against governments who orchestrate war, it is often misconstrued as dealing directly with the Vietnam War. However the song was written at the beginning of 1963, when only a few hundred Green Berets were stationed in South Vietnam. The song only came to be re-appropriated as a comment on Vietnam in 1965, when US planes bombed North Vietnam for the first time, with lines such as “you that build the death planes” seeming particularly prophetic (in fact, unlike many of his contemporary 'protest singers', Dylan never mentioned Vietnam by name in any of his songs). Dylan is quoted as saying that the song "is supposed to be a pacifistic song against war. It's not an anti-war song. It's speaking against what Eisenhower was calling a military-industrial complex as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up."[26] Similarly ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ (1963) is often perceived to deal with the Cuban missile crisis, however Dylan performed the song more than a month before John F. Kennedy's TV address to the nation (October 22, 1962) initiated the Cuban missile crisis. After this brief, but extremely fruitful, 20 month period of 'protest songs', Dylan decided to extract himself from the movement, changing his musical style from folk to a more rock-orientated sound, and writing increasingly abstract lyrics, which had more in common with poetry and biblical references than social injustices. As he explained to critic Nat Hentoff in mid-1964: “Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore - you know, be a spokesman. From now on, I want to write from inside me …I’m not part of no movement… I just can’t make it with any organisation…”.[22] His next acknowledged 'protest song' would be "The Hurricane", written twelve years later in 1976.

Pete Seeger, formerly of The Almanacs and The Weavers and a major influence on Dylan and his contemporaries, continued to be a strong voice of protest in the 1960s, when he produced "Where Have All the Flowers Gone", and "Turn, Turn, Turn" (written during the 1950s but released on Seeger's 1962 album The Bitter and The Sweet). Seeger's song "If I Had a Hammer" had been written in 1949 in support of the progressive movement, but rose to Top Ten popularity in 1962 when covered by Peter, Paul and Mary), going on to become one of the major Civil Rights anthems of the American Civil Rights movement. "We Shall Overcome", Seeger's adaptation of an American gospel song, continues to be used to support issues from labor rights to peace movements. Seeger was one of the leading singers to protest against then-President Lyndon Johnson through song. Seeger first satirically attacked the president with his 1966 recording of Len Chandler's children's song, "Beans in My Ears". In addition to Chandler's original lyrics, Seeger sang that "Mrs. Jay's little son Alby" had "beans in his ears", which, as the lyrics imply,[27] ensures that a person does not hear what is said to them. To those opposed to continuing the Vietnam War the phrase suggested that "Alby Jay", a loose pronunciation of Johnson's nickname "LBJ", did not listen to anti-war protests as he too had "beans in his ears". Seeger attracted wider attention in 1967 with his song "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy", about a captain — referred to in the lyrics as "the big fool" — who drowned while leading a platoon on maneuvers in Louisiana during World War II. In the face of arguments with the management of CBS about whether the song's political weight was in keeping with the usually light-hearted entertainment of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, the final lines were "Every time I read the paper/those old feelings come on/We are waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on." And it was not seriously contested[citation needed] that much of the audience would grasp Seeger's allegorical casting of Johnson as the "big fool" and the Vietnam War the foreseeable danger. Although the performance was cut from the September 1967 show, after wide publicity,[28] it was broadcast when Seeger appeared again on the Smothers' Brothers show in the following January.

Phil Ochs, one of the leading protest singers of the decade (or, as he preferred, a "topical singer"), performed at many political events, including anti-Vietnam War and civil rights rallies, student events, and organized labor events over the course of his career, in addition to many concert appearances at such venues as New York City's The Town Hall and Carnegie Hall. Politically, Ochs described himself as a "left social democrat" who turned into an "early revolutionary" after the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, which had a profound effect on his state of mind.[29] Ochs summarised protest songs thus: "A protest song is a song that's so specific that you cannot mistake it for bullshit" [30] Some of his best known protest songs include "Power and the Glory", "Draft Dodger Rag", "There But for Fortune", "Changes", "Crucifixion, "When I'm Gone", "Love Me I'm a Liberal", "Links on the Chain", "Ringing of Revolution", and "I Ain't Marching Anymore".Other notable voices of protest from the period included Joan Baez, , Buffy Sainte-Marie (whose anti-war song "Universal Soldier" was later made famous by Donovan) and Tom Paxton ("Jimmy Newman" - about the story of a dying soldier, and "My Son John" - about a soldier who returns from war unable to describe what he's been through), among others. The first protest song to reach number one in the United States was Eve of Destruction by Barry McGuire in 1965.[31].

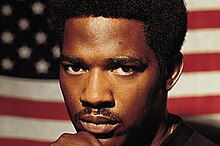

The American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s often used Negro spirituals as a source of protest, changing the religious lyrics to suit the political mood of the time. The use of religious music helped to emphasize the peaceful nature of the protest; it also proved easy to adapt, with many improvised call-and-response songs being created during marches and sit-ins. Some imprisoned protesters used their incarceration as an opportunity to write protest songs. These songs were carried across the country by Freedom Riders,[32] and many of these became Civil Rights anthems. Many soul singers of the period, such as Sam Cooke ("A Change Is Gonna Come" (1965)), Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin ("Respect"), James Brown ("Say It Loud - I'm Black and I'm Proud"[1968]; "I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door, I’ll Get It Myself) ” [1969]) and Nina Simone ("Mississippi Goddam" (1964), "To Be Young, Gifted and Black" (1970)) wrote and performed many protest songs which addressed the ever-increasing demand for equal rights for African Americans during the American civil rights movement. The predominantly white music scene of the time also produced a number of songs protesting racial discrimination, including Janis Ian's "Society's Child (Baby I've Been Thinking), (1966)" about an interracial romance forbidden by a girl's mother and frowned upon by her peers and teachers and a culture that classifies citizens by race.[33] Steve Reich's 13-minute long "Come Out" (1966), which consists of manipulated recordings of a single spoken line given by an injured survivor of the Harlem Race Riots of 1964, protested police brutality against African Americans.

In the 1960s and early 1970s many protest songs were written and recorded condemning the War in Vietnam, most notably "Simple Song of Freedom" by Bobby Darin, "The War Drags On" by Donovan (1965),"I Ain't Marching Anymore" by Phil Ochs (1965), "Lyndon Johnson Told The Nation" by Tom Paxton (1965), "Bring Them Home" by Pete Seeger (1966), "Requiem for the Masses" by The Association (1967), "Saigon Bride" by Joan Baez (1967), "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy" by Pete Seeger (1967), "Suppose They Give a War and No One Comes" by The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band(1967), "The "Fish" Cheer / I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-To-Die Rag" by Country Joe and the Fish (1968)[34] "One Tin Soldier" by Original Caste (1969), "Volunteers" by Jefferson Airplane (1969), and "Fortunate Son" by Creedence Clearwater Revival (1969). Woody Guthrie's son Arlo Guthrie also wrote one of the decade's most famous protest songs in the form of the 18 minute long talking blues song "Alice's Restaurant Massacree", a bitingly satirical protest against the Vietnam War draft. As an extension of these concerns, artists started to protest the ever-increasing escalation of Nuclear weapons and threat of Nuclear warfare; as for example on Tom Lehrer's ""So Long, Mom (A Song for World War III)", "Who's Next?" (about Nuclear proliferation) and "Wherner von Braun"[35] from his 1965 collection of political satire songs That Was the Year That Was.

The 1960s also saw a number of successful protest songs from the opposite end of the spectrum; the political right which supported the war. Perhaps the most successful and famous of these was "Ballad of the Green Berets" (1966) by Barry Sadler, which was one of the very few songs of the era to cast the military in a positive light and yet become a major hit. Merle Haggard & the Strangers' “Okie from Muskogee” (1969), despite being strongly patriotic, was listed in PopMatters' July 2007 list of the top 65 protest songs because it is, as the webzine puts it,

in fact a protest against changing social mores, alternative lifestyles, and, well, protests[...] In a time when protest songs filled the airwaves, it is ironic that Haggard scored his biggest hit protesting the rise of a discontented culture.[33]

1970s; The Vietnam War, Soul Music

The Kent State shootings of May 4 1970 amplified sentiment against the United States' invasion of Cambodia and the Vietnam War in general, and protest songs about The Vietnam War continued to grow in popularity and frequency. Anti-war songs such as Chicago's "It Better End Soon" (1970), "War" (1970) by Edwin Starr, "Ohio" (1970) by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young (about the May 4th Kent State shootings), and "Imagine" (1971) by John Lennon captured the spirit of the time. Another great influence on the anti-Vietnam war protest songs of the early seventies was the fact that this was the first generation where combat veterans were returning prior to the end of the war, and that even the veterans were protesting the war, as with the formation of the 'Vietnam Veterans Against the War' (VVAW). Graham Nash wrote his "Oh! Camil (The Winter Soldier)" (1973) to tell the story of one member of VVAW, Scott Camil. Other notable anti-war songs of the time included "Peace Train" by Cat Stevens (1971), "War Pigs" by Black Sabbath (1971), and Stevie Wonder's frank condemnation of Richard Nixon 's Vietnam policies in his 1974 song "You Haven't Done Nothin'." Protest singer and activist Joan Baez dedicated the entire B side of her album Where Are You Now, My Son? (1973) to recordings she had made of bombings while in Hanoi.

While war continued to dominate the protest songs of the early 70s, there were other issues addressed by bands of the time, such as Helen Reddy's feminist hit "I Am Woman" (1972), which became an anthem for the women’s liberation movement. Bob Dylan also made a brief return to protest music after some twelve years with "Hurricane" (1976), which protested the imprisonment of Rubin "Hurricane" Carter as a result of alleged acts of racism and profiling against Carter, which Dylan describes as leading to a false trial and conviction.

Soul music carried over into the early part of the 70s, in many ways taking over from folk music as one of the strongest voices of protest in American music, the most important of which being Marvin Gaye's seminal 1971 protest album "What's Going On", which included "Inner City Blues", "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)", and the title track. Another hugely influential protest album of the time was poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron's "Small Talk at 125th and Lenox", which contained the oft-referenced protest song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised". The album's 15 tracks dealt with myriad themes, protesting the superficiality of television and mass consumerism, the hypocrisy of some would-be Black revolutionaries, white middle-class ignorance of the difficulties faced by inner-city residents, and fear of homosexuals.

1980s; Anti-Reagan protest songs, and The Birth of Rap