Cornish people: Difference between revisions

Ehrenkater (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

====Early records==== |

====Early records==== |

||

Early signs of human habitation emerge in the fourth millenium BCE, with examples of the Cornish [[ |

Early signs of human habitation emerge in the fourth millenium BCE, with examples of the Cornish [[Neolithic]], [[Bronze Age]] and [[Iron Age]] at [[Chûn Quoit]], [[Boscawen-Un]] and [[Chysauster Ancient Village]] respectively <ref>http://www.megalithics.com/england/chun/chunmain.htm</ref> <ref>http://www.historic-cornwall.org.uk/a2m/neolithic/chambered_tomb/chun_quoit/chun_quoit.htm</ref> |

||

<ref>http://www.stone-circles.org.uk/stone/chun.htm</ref> <ref>http://www.cornwalltour.co.uk/chun_quoit.htm</ref> <ref>Burl, Aubrey (2000). The stone circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. Yale University Press. Ch.9.</ref> <ref>Cope, Julian (1998). The Modern Antiquarian: A Pre-Millennial Odyssey Through Megalithic Britain. HarperCollins p164</ref> <ref>Weatherhill, Craig (2000). Cornovia: Ancient sites of Cornwall and Scilly. Cornwall Books</ref> <ref>Weatherhill, Craig (1995). Cornish Place Names & Language. Sigma Leisure</ref>. The earliest known Classical reference to Cornwall dates from 60 BCE when the Greek historian [[Diodorus Siculus]] quoted [[Pytheas]], naming the southwestern peninsula of Britain (including Cornwall) ''Belerion'' ("The Shining Land") and discussing the tin trade at "Ictis", generally identified with [[St. Michael's Mount]].<ref>http://www.roman-britain.org/places/ictis.htm</ref> <ref>Cunliffe, Barry (2002). The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek: The Man Who Discovered Britain (Revised ed.). Walker & Co, Penguin</ref> |

|||

====Dark and Middle Ages==== |

====Dark and Middle Ages==== |

||

Revision as of 11:20, 1 July 2009

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Uncertain:

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

English (see West Country dialects) · Cornish | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||

The Cornish people (Template:Lang-kw) are an ethnic group of the United Kingdom, originating in Cornwall.[3][5] Cornish may also refer to the many descendants of people who have come and settled in Cornwall and who have adopted this identity,[6][page needed] and there are also many people around the world who are descended from the Cornish diaspora who claim a Cornish identity.[7][8][9][10][page needed]

History

Genetic origins

The Cornish people are primarily descended from the peoples who inhabited the southwestern peninsula of Great Britain in pre-Roman times.[citation needed] During the Roman period a Brythonic tribe known to the Romans as the Dumnonii were the principal tribe inhabiting what is now Cornwall as well as Devon and Somerset. There is also mention of the Cornovii (Cornish) during the later post-Roman period. For this reason there is considered to be kinship with the Welsh and especially Breton peoples- more distantly with the Scots, Manx and Irish. There also seems to have been some Irish settlement of Cornwall in the sub-Roman period too, attested to by the presence of Ogham script stones. Connections between the Celtic Christians in Britain and Ireland mean that some degree of cultural exchange was inevitable and many Cornish Saints appear to have possible Irish origins. It has even been speculated[by whom?] that Saint Piran, the widely-held patron saint of Cornwall, is in actual fact[weasel words] the Irish Saint Ciaran[11][page needed][12][page needed][13][page needed][14][page needed][15][page needed][16][page needed][17][page needed]

Y chromosome analysis of samples from the British Isles, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Friesland, and the Basque Country have shown that Cornish men's Y chromosomes are generally more similar to those of the assumed indigenous population (Welsh/Irish/Basque) than are those of men from other parts of England or Scotland. However more Y chromosomes from Cornwall showed Germanic (Danish/German/Frisian) influence than those from Wales, Ireland or the Basque Country. It should be noted that samples from all parts of the British Isles show an indigenous component.[18]

In 2005, professor Sir Walter Bodmer was appointed to lead a £2.3 million project (roughly 4.5 million USD) by the Wellcome Trust at Oxford University to examine the genetic makeup of the United Kingdom. The findings, published on Channel 4's Faces of Britain in April 2007[19] show that the Cornish people have a particular variant of the MC1R gene identifying them as a Celtic race more closely related to the Welsh, Irish and Breton peoples than to their English neighbours.

In Blood of the Isles, by Brian Sykes[20][page needed] and Origins of the British, by Stephen Oppenheimer, [21][page needed] both authors claim that according to genetic evidence, most Cornish people and most Britons descend from an ancient (Paleolithic) population of the Iberian Peninsula, as a result of different migrations that took place during the Mesolithic and the Neolithic which laid the foundations for the present-day populations in the British Isles, indicating an ancient relationship among the populations of Atlantic Europe.

The genetic marker(s) M167-SRY2627 forming the haplogroup R1b1b2a1b3 (R1b1c6) has been attributed to the Cornish people[4]. This group is calculated to have originated 2,850 BP and is predominantly found in Spain (esp. Catalonia), Western France, Cornwall, Wales, and the Basque country among Catalans, Gascons, Bretons and Cornish respectively. The so-called Italo-Celtic haplogroup R1b1b2a1b with markers P312-S116 is calculated to have originated 4,500 BP and is found in Western Europe. [22]

Mythological origins

An ancient legend, the Brutus Myth, recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth, gives explicit reference to the Cornish people in describing their descent.[citation needed] The legend tells how Albion was colonised by refugees from Troy under Brutus, how Brutus renamed his new Kingdom, Britain, and how the island was subsequently divided up between his three sons, the eldest inheriting England and the other two Scotland and Wales. Additionally according to the legend there were two groups of Trojans who originally arrived in Britain. The smaller group was led by a warrior named Corineus, to whom Brutus granted extensive estates. And just as Brutus had ‘called the island Britain…and his companions Britons’, so Corineus called ‘the region of the kingdom which had fallen to his share Cornwall, after the manner of his own name, and the people who lived there... Cornishmen’.[citation needed]

The first account of Cornwall comes from the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (c.90 BCE–c.30 BCE), supposedly quoting or paraphrasing the fourth-century BCE geographer Pytheas, who had sailed to Britain:

[The inhabitants of that part of Britain called Belerion or the Land's End] from their intercourse with foreign merchants, are civilised in their manner of life. They prepare the tin, working very carefully the earth in which it is produced…Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhône.[23]

Who these merchants were is not known. There is no current evidence for the theory that they were Phoenicians.[24]

No other region is picked out for such special treatment; the historian Dr Mark Stoyle has suggested that this shows that, as far as Geoffrey was concerned, Cornwall possessed a separate identity. Cornishmen and women continued to regard themselves as descendants of Corineus until well into the early modern period.[25][page needed]

Historical events

Early records

Early signs of human habitation emerge in the fourth millenium BCE, with examples of the Cornish Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age at Chûn Quoit, Boscawen-Un and Chysauster Ancient Village respectively [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33]. The earliest known Classical reference to Cornwall dates from 60 BCE when the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus quoted Pytheas, naming the southwestern peninsula of Britain (including Cornwall) Belerion ("The Shining Land") and discussing the tin trade at "Ictis", generally identified with St. Michael's Mount.[34] [35]

Dark and Middle Ages

The Kingdom of Cornwall began to emerge in the sub-Roman era. Modern Cornwall finds itself in territory which included the tribes known to the Romans as the Dumnonii and later the Cornovii – mentioned in the Ravenna Cosmography. The Kingdom of Cornwall emerged from the "shadowy", semi-legendary Kingdom of Dumnonia around the 6th century AD.[36].

The power vacuum left by the Roman abandonment of Britannia led to the formation of petty kingdoms. This was also the period of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of England. This brought the native Britons or Romano-Britons into conflict with the Anglo-Saxons. In 577 The Battle of Deorham near Bristol resulted in the separation of the West Welsh (i.e. the Cornish) from the Welsh- the two peoples effectively cut off by a Saxon wedge driven between them. The period is marked by a series of conflicts between Wessex and the Dumnonian/Cornish kingdom. The territory under Brythonic control gradually receded in the wake of the Saxon advance. In 927, according to William of Malmesbury who was writing c1120, Athelstan the king of Wessex evicted the "Cornish" from Exeter and perhaps the rest of Devon: "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race".[37][page needed] A key moment in the history of the Cornish people was in 936 when Athelstan set the border between Cornwall and England at the east bank of the River Tamar, thus defining the approximate modern area of Cornwall.[38]

The Norman conquest of England in 1066 brought more changes in power and territory for the whole of England and also Cornwall (at this time at least not considered part of England). According to William of Worcester, writing in the 15th century, Cadoc was the last survivor of the Cornish royal line at the time of the Norman conquest.[39][page needed] Following his conquest, William the Conqueror installed his half-brother, the Breton speaking Breton Robert, Count of Mortain, as the Earl of Cornwall. William was King of England and the "province of the Britons".[citation needed]

Cornish rebellions and Civil War

The history of Cornwall is fairly non-eventful throughout the Norman period and late Middle Ages until 1497. 1497 saw two Cornish uprisings, the First Cornish Rebellion and the Second Cornish Rebellion. On a wider scale the whole of England had already been thrown into turmoil by the revolts led by Perkin Warbeck, culminating in the Battle of Deptford Bridge, London with disastrous consequences for the Cornish rebels who found themselves on the losing side. [40] 1497 || Second Cornish Uprising of 1497 led by Perkin Warbeck.[41] Severe monetary penalties, were extracted from the Cornish by Crown agents with the result that large sections of Cornish society were impoverished for years to come. Cornish prisoners were sold into slavery with their estates seized and handed to more "loyal" subjects.

The Cornish leaders of the rebellion, Michael Joseph An Gof and Thomas Flamank, were both sentenced to the traitor's death of hanging, drawing and quartering. However they "enjoyed" the king's mercy and were allowed to hang until dead before being decapitated. They were executed at Tyburn on 27 June 1497. An Gof is recorded to have said before his execution that he should have "a name perpetual and a fame permanent and immortal". Thomas Flamank was quoted as saying "Speak the truth and only then can you be free of your chains".[citation needed] Their heads were then displayed on pike-staffs ("gibbeted") on London Bridge[42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] [50] .

After half a century the Cornish rebelled again, in the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549. The roots of this conflict can be traced back to the Cornish Rebellion of 1497 and the forced introduction of the English language Book of Common Prayer, resulting in a decline of the Cornish language and Cornish cultural identity. Some 4,000 rebels were killed and eventually up to 11% of the Cornish population were slaughtered by English forces. After 1549, the term "Anglia et Cornubia" was no longer used in official documents.[51] The Prayer Book Rebellion brought great suffering to the Cornish people and resulted in subsequent radical changes of religion and the Cornish language.

The English Civil War saw conflict in Cornwall again. Most of the Cornish were strongly Royalist, and in 1642 the First Battle of Lostwithiel was a resounding victory.[citation needed] This was followed in 1643 by the Battle of Braddock Down on 19 January 1643, again a victory for the Royalists under Sir Ralph Hopton, which secured Cornwall for King Charles I of England. However the English Civil Wars ended in Parliamentarian victory, the Cornish yet again finding themselves in the losing side and having done much to estrange themselves from the victorious party.[citation needed] Sentiments lingered for a while, and 1648 saw The Gear Rout, an insurrection in Cornwall involving some 500 Cornish rebels who fought on the rebel Royalist side against the Parliamentarian forces of Sir Hardress Waller; this resulted in an ignominious defeat for the Cornish - once again rebels and on the wrong side of the law as far as Parliament was concerned.

Nonconformism

The 18th century was far more peaceful than the 17th century had been. The tin industry in Cornwall prospered, along with fishing. The area had always known isolation and poverty but it was largely but not entirely to be left behind by the forthcoming Industrial Revolution. Major changes in Cornish society at this time were the practical death of the Cornish language, now lingering only in far west Penwith, along with the inroads made by Nonconformist sects, including the Quakers and Methodismunder the leadership of John Wesley [52] [53][54] [55][56][57]. One notable event occurred in 1801, when Richard Trevithick built a full-size steam locomotive; in Cornwall Richard Trevithick is widely held as the inventor of the "steam train"[citation needed].

Empire, emigration and romanticism

In 1856, the courts saw the historic Cornish Foreshore Case. Originally a case of arbitration between the Crown and the Duchy of Cornwall, it was monumental for later Cornish nationalist political thinking in that the Officers of the Duchy of Cornwall successfully argued that the Duchy enjoyed many of the rights and prerogatives of a County palatine and that although the Duke of Cornwall was not granted Royal Jurisdiction, he was considered to be quasi-sovereign within his Duchy of Cornwall. This case is often cited by those who claim non-county status for Cornwall in terms of her relations with England and/or the United Kingdom [58][59] [60][61][62][63].

The latter half of the 19th century saw the Cornish diaspora [64]. An estimated 250,000 Cornish people emigrated to various parts of the British Empire in search of a better standard of living and more opportunities. Their destinations were primarily Australia [65], the Americas [66] and, later, Southern Africa [67]. This mass emigration led to Cornish mining expertise being spread around the world, along with some aspects of traditional Cornish culture. To this day there are communties around the world who are aware of and also celebrate their Cornish roots [68] [69] [70].

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a rise in awareness of Cornwall's ancient language and culture. This led in 1928 to the First Gorseth Kernow at Boscawen-un, instituted by Henry Jenner, symbolising the resurgent interest in Cornwall's Celtic cultural and linguistic heritage. Following this resurgence in cultural feeling, in 1951 the Cornish (civic) nationalist party Mebyon Kernow was formed in order to campaign for greater recognition of Cornish "indigenous" or "traditional" culture and a greater degree of self-determination for the people of Cornwall.

Ice-creams and deck-chairs

Post-Second World War Cornwall witnessed a great decline in the traditional industries of tin mining and fishing, a fate shared by other industries in the United Kingdom. Owing to her geographical location Cornwall began to rely heavily on tourism as its main economic resource. Cornwall also became a prime destination for second-home owners. This led to a feeling of resentment in certain sections of the Cornish community, and prompted David Penhaligon MP, in the 1980s, to protest in a speech made in Camborne that a people's future could not be built on "ice-creams and deck-chairs", referring to the tourism industry. The high price of housing and lack of employment opportunities led to many younger Cornish born people leaving, while many pensioners came to Cornwall [71][72]. Thus the demographics of Cornwall changed, with an ageing population, as well as a shift in the sense of Cornish identity [73] [74] [75].

The 1970s saw some conflict concerning Cornwall's "official" status. In 1971 the Kilbrandon Report into the British constitution recommended that, when referring to Cornwall, official sources should cite the "Duchy" rather than the "County". This was suggested in recognition of its constitutional position. This was followed in 1977 by the Plaid Cymru MP Dafydd Wigley confirming in Parliament [clarification needed]that the Stannators' right to veto Westminster legislation.[76]

"Cornishness" in the modern period

The concept of "Cornishness" has been examined in numerous different ways with methodological tools varying from feminist theory to deconstructionism.[77]

Increasing campaigning and awareness of Cornwall's economic, demographic and cultural issues led to the landmark 2001 Census.[citation needed] In 2001 the "Cornish" were allocated the ethnic code "06" for the 2001 UK Census (see UK Census 2001 Ethnic Codes) for the first time ever. In the same year a petition in favour of a Cornish Assembly, carrying the signatures of over 50,000 people, is handed into 10 Downing Street on Wednesday 12 December 2001.[78] By 2002- The Cornish language had been officially[clarification needed] recognised by the British Government.[79]

In the United Kingdom Census 2001, the population of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly was estimated to be 501,267.[80] The number of people living in Cornwall who consider themselves to be more Cornish than British or English is uncertain. One survey found that 35.1% of respondents identified as Cornish, with 48.4% of respondents identifying as English, a further 11% thought of themselves as British.[81] A Morgan Stanley survey in 2004 indicated that 44% of people in Cornwall identify as Cornish rather than English or British,[82] and there have been recent calls for more accuracy in the recording of the number who identify as Cornish in the 2011 Census.[83]

For the first time for a census in the United Kingdom, those wishing to describe their identity as Cornish were given their own code number (06) on the 2001 UK Census form, alongside those for people wishing to describe themselves as English, Welsh, Irish or Scottish.[84] About 34,000 people in Cornwall and 3,500 people in the rest of the UK wrote on their census forms in 2001 that they considered their ethnic group to be Cornish.[85] This represented nearly 7% of the population of Cornwall, and is therefore a significant phenomenon.[neutrality is disputed][86] Although happy with this development, campaigners expressed reservations about the lack of publicity surrounding the issue, the lack of a clear tick-box for the Cornish option on the census and the need to deny being British in order to write "Cornish" in the field provided. The UK government has agreed recently that English and Welsh will have an identity tick box on the Census 2011 but there will be no Cornish option tick box. Various Cornish organisations are campaigning for the inclusion of the Cornish tick box on the next 2011 Census[87][88] and Cornish "was one of the most requested ethnic groups for the 2011 Census.[89]

A 2000 speech by Tony Blair included the Cornish as an example of the multiple political allegiances of the modern Union: “We can comfortably be Scottish and British or Cornish and British or Geordie and British or Pakistani and British”.[90]

Many surnames and also a lot of first names from Cornwall are derived from the Cornish language. Typically the surnames that begin with the Cornish language prefixes "tre-", "pol-" and "pen-", giving rise to the old rhyme By Tre, Pol and Pen shall ye know all Cornishmen.[91] [92] Many Cornish surnames and place names still retain these words as prefixes, such as the name Trelawny and the town of Polperro. Tre in the Cornish language means a settlement or homestead; Pol, a pond, lake or well; and Pen, a hill or headland.

Geographic distribution

Outward migration in search of employment and/or a higher standard of living has been a factor in Cornish history since at least the 18th century. It has been estimated that some 250,000 Cornish people left Cornwall between 1861 and 1901 and that these emigrants included many occupations such as farmers, merchants and tradesmen, nevertheless miners made up most of the numbers. There is a well known saying in Cornwall that "a mine is a hole anywhere in the world with at least one Cornishman at the bottom of it!"[93]

A driving force for some emigrants was the opportunity for skilled miners to find work abroad, later in combination with the decline in the tin and copper mining industries in Cornwall. Migration became so common that a slang term to describe a Cornish migrant abroad appeared: "Cousin Jack"[94].

Today, in the USA, Canada, Mexico, Australia, South Africa, Brazil and other countries, some of the descendants of these original migrants celebrate their Cornish ancestry and remain proud of the Cornish surnames they carry.

Continuity in the sense of a Cornish identity is evidenced by the existence of both Cornish societies and Cornish festivals in these countries, such as the Cornish Association of Witwatersrand in South Africa [95] as well as a growing overseas interest in the Cornish language. In Moonta, Australia, the Kernewek Lowender [5] festival is the largest Cornish festival in the world and attracts tens of thousands each year. Historically, Moonta settled by Cornish miners and their families and is known to this day as Australia's Little Cornwall. Moonta is most famous for its traditional Cornish pasties and its Cornish style miner's cottages and mine engine houses such as Richman's and Hughes engines houses built in the 1860s.[96]

Cornish ethnicity is also recognised on the Canadian census, and in 2006, 1,550 Canadians listed their ethnic origin as Cornish.[3]

In London, there is the London Cornish Society, its first annual dinner having been held in 1885 and also London Cornish RFC (rugby football club) established in 1962.[97].

Culture

Language

English and Anglo-Cornish dialect

Although English was not the original language spoken in Cornwall and by most Cornish people, for obvious[weasel words] historical reasons it has become the main language used in Cornwall today. English had mostly replaced the Cornish language as the main language of communication by the 18th century.

A distinct dialect of English can also be found in Cornwall, and appears in many popular[weasel words] Cornish folksongs such as Camborne Hill. To an extent, the accent and dialect is a badge of "Cornishness" for some people, but interest in Anglo-Cornish has been overshadowed by the Cornish language recently.

The Anglo-Cornish dialect itself, has the most substantial Celtic language influence or linguistic substrate of the West Country dialects.[98][99] The extreme western areas of Cornwall retained their Celtic language and were non-English speaking into the early modern period. In places such as Mousehole, Newlyn and St Ives, fragments of Cornish survived in English even into the 20th century, e.g. some numerals (especially for counting fish) and the Lord's Prayer were noted by W. D. Watson in 1925, Edwin Norris collected the Creed in 1860, and J. H. Nankivel also recorded numerals in 1865. The dialect of West Penwith is particularly distinctive, especially in terms of grammar. This is most likely due to the late decay of the Cornish language in this area. In Cornwall the follwing places were included in the Survey of English Dialects: Altarnun, Egloshayle, Gwinear, Kilkhampton, Mullion, St Buryan, and St Ewe.

The Anglo-Cornish dialect contains many words which are in themselves derived from the Cornish language or Middle English words used by Cornish and now defunct in other English dialects. [100].

- Gweggan- small fish

- Gwidgygwee- small black spot caused by pinch or bruise

- Padgypaow- a lizard, or pajerpaw a "newt"

- Pednameen- head-an-point

- Pednhateen-head and tail (like pilchards in a barrel)

- Pednpral- horse's head

- Pednpaley- (Bird) bluetit

- Pednjowl- a term of abuse. 'Devil's head'

- Teddyoggy- a Cornish pasty (from Cornish "hogen"- "pie")

- Emmet- from Middle English "ant"- used disparigingly of tourists

The Cornish dialect and "accent" are generally considered to be part of the West Country dialect continuum and to a non-local person might sound stereotypically "rural" often heard in "television" or "radio" portrayals of the peoples west of Bristol. There is however a lot of difference in the South West and Cornish people also note a difference in accent between West Cornwall and East Cornwall. East Cornwall accents tend to be closer to those of Devon, perhaps owing to the longer history of English being spoken in the eastern regions of Cornwall and their natural closer proximity. West Cornwall on the other hand has had a longer history of the Cornish language being spoken and influencing the English of the people of West Cornwall.[101]

The differences between Anglo-Cornish dialect and English/English regional pronunciation(s) are noted here. Only the differences have been included as these are sounds not found in English or other English dialects [102].

Anglo-Cornish dialect has a vowel system similar to Old English and Cornish.

- aa - this sound does not exist in English, as in Cornish tan ‘fire’

- (e.g. Dialect baal ‘mine’ and aant ‘aunt’)

- ae - this sound does not exist in English, as in Cornish men ‘stone’

- (e.g. Dialect aeven ‘throwing’ and maenolas ‘wooden box stove’)

- oa - this sound does not exist in English, as in Cornish mos ‘to go’

- (e.g. Dialect troaz ‘noise’ and noa ‘no’)

Diphthongs in the Anglo-Cornish dialect.

- ow - this sound does not exist in English, as in Cornish tewynn ‘dune’

- (e.g. Dialect towan ‘dune’ and crowst ‘lunch’)

The dialect has pre-occluded geminates that derive from both Cornish and Middle English.

- dn - this sound does not exist in Modern English, as in Late Cornish pedn ‘head’, similar to the old pronunciation of "Wednesday"

- (e.g. Dialect pednan ‘small piece of turf’ and wodn ‘would not’)

- bm - this sound does not exist in English, as in Late Cornish cabm ‘head’

- (e.g. Dialect scubma ‘splinters’ and obm ‘of it’)

The Cornish comedian Jethro uses what many would describe as a typical Cornish accent and dialect in his comedy sketches.

Ballad of Tom Bawcock

Tom Bawcock’s Eve is a folk event celebrated in Mousehole, West Penwith and is usually accompanied by the Ballad of Tom Bawcock. The Anglo-Cornish dialect words here were noted by Robert Morton Nance c1930 [103] .

- A merry plaas you may believe/ A merry place you may believe

- woz Mowsel pon Tom Bawcock’s Eve./ was Mousehole upon Tom Bawcock' Eve.

- To be theer then oo wudn wesh/ To be there who wouldn't wish

- To sup o sibm soorts o fesh!/To sup of seven sorts of fish!

- Wen morgee brath ad cleard tha path/ When murgy broth had cleared rhe path

- Comed lances for a fry,/Corned lances for a fry,

- An then us had a bet o scad/ And then we had a bit of scad (horse mackerell)

- an starry gazee py./and Starry Gazy Pie.

- Nex cumd fermaads, braa thustee jaads/ Next came fairmaids, brave thrusty jades

- As maad ar oozles dry,/ As made our throats dry

- An ling an haak, enough to maak/ And ling and hake enough to make,

- a raunen shark to sy!/ a ravenous shark to sigh!

- A aech wed clunk as ealth wer drunk/ And each we would drink as health were toasted

- En bumpers bremmen y,/ In tankards filled brimming high,

- An wen up caam Tom Bawcock’s naam/ And when up came, Tom Bawcock's name

- We praesed un to tha sky/ We praised him to the sky

The Cornish language

The Cornish language is seen by many as the cultural backbone of the Cornish identity, although only 3,500 people in Cornwall speak it to a basic conversational level and only around a tenth of those fluently. The Cornish language of today has had a number of different orthographies since its revival began in 1904, each based on a certain period in Cornish literary history. Cornish died out as a main community language sometime in the late 18th or possibly 19th centuries.

Dolly Pentreath is often regarded as the last native speaker of the language though evidence also points to it still being spoken right up to the dawn of the 20th century. Recently the Cornish language has been recognised by the UK and EU for protection as a UK minority language and now receives funding from both these bodies, and in 2008 a standard written form was agreed that unites the different orthographies. The Cornish language is a Brythonic language related to Welsh and Breton.

In June 2005, after much pressure from language groups and groups such as the Gorseth Kernow, the government allocated £80,000 per year for three years of direct central government funding to the Cornish language. Although pleased with this development, there have been concerns however that in the same period for example the Ulster Scots language is being allocated £1,000,000 per year of direct government funding. This comes after the British government acknowledged in its 1st European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages compliance report that: "There are no current demands from within the school system for Ulster-Scots to be taught as a language. There have been concerns that while the ECRML Level II Cornish language remains in the slow lane, the Ulster-Scots language is to be made a ECRML Level III language.[104][105]

Festivals and events

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. |

This article duplicates the scope of other articles. |

Cornwall has many events, some old,[clarification needed] some new[clarification needed] and some revived the celebrate the diverse culture of the area.

Saint Piran's Day

St Piran's Day held on 5 March every year. The day is named after one of the patron saints of Cornwall, Saint Piran.

The modern observance of St Piran's day as a festival for the people of Cornwall dates back to the early Cornish revival period, 19th and early 20th century when Celtic revivalists sought to provide the people of Cornwall with a national day not unlike those observed in other nations. Since the 1950s, the celebration has become increasingly observed and since the start of the 21st century almost every Cornish community holds some sort of celebration to mark the event. Saint Piran's Flag is also seen flying throughout Cornwall on this day.

St Piran's day is also celebrated annually in Grass Valley, California to honor the Cornish miners who participated in the area's mining history beginning in the mid 19th century.[106]

Helston Flora Dance

The Furry Dance, also known as The Flora ( takes place in Helston, Cornwall, and is one of the oldest British customs still practised today.[107] The dance is very well attended every year and people travel from all over the world to see it: Helston Town Band play all the music for the dances. The Furry Dance takes place every year on 8 May (or the Saturday before if 8 May falls on a Sunday or Monday), and is a celebration of the passing of Winter and the arrival of Spring. Traditionally, the dancers wear lily of the valley, which is Helston's symbolic flower. The gentlemen wear it on the left, with the flowers pointing upwards, and the ladies wear it upside down on the right.

Padstow Obby Oss

Padstow, in Cornwall, is internationally famous[citation needed] for its traditional[clarification needed] Obby 'Oss day (dialect for Hobby Horse). Held annually on May Day (1 May), which in Cornwall, largely dates back to the Celtic Beltane, the day celebrates the coming of Summer. The festival itself starts at midnight on May 1 with unaccompanied singing around the town starting at the Golden Lion Inn. By the morning, the town is dressed with greenery, flowers and flags, with the focus being the maypole. although the earliest mention of the Obby 'Oss at Padstow dates from 1803. An earlier hobby horse is mentioned in the Cornish language drama Beunans Meriasek, a life of the Camborne saint, where it is associated with a troupe, or "companions." Some say that the festival pre-Christian origins, such as in the Celtic festival of Beltane in the Celtic nations, and the Germanic celebrations during the Þrimilci-mōnaþ (literally Three-Milking Month or Month of Three Milkings) [108] in England[109].[110]. Worship of horse deities such as Epona was found in ancient Celtic societies.

Mazey Day

"Mazey Day" or Golowan in Cornish is the name for the Midsummer celebrations in Cornwall: widespread prior to the late 19th century and most popular in the Penwith area and in particular Penzance and Newlyn. The celebrations were conducted from the 23rd of June (St John's Eve) to the 28th of June (St Peter's Eve) each year, St Peter's Eve being the more popular in Cornish fishing communities. The celebrations were centred around the lighting of bonfires and fireworks and the performance of associated rituals. The midsummer bonfire ceremonies (Tansys Golowan in Cornish) were revived at St Ives in 1929 by the Old Cornwall Society [111] and since then spread to other societies across Cornwall, as far as Kit Hill near Callington. Since 1991 the Golowan festival in Penzance has revived many of these ancient customs and has grown to become a major arts and culture festival: its central event 'Mazey Day' now attracts tens of thousands of people to the Penzance area in late June.

Tom Bawcock's Eve

Tom Bawcock's Eve is a festival held on the 23rd of December in Mousehole, The festival is held in celebration and memorial of the efforts of Mousehole resident Tom Bawcock to lift a famine from the village. During this festival Star Gazy pie (a mixed fish, egg and potato pie with protruding fish heads) is eaten and depending on the year of celebration a lantern procession takes place

Newquay Surfing

Newquay regularly hosts international surfing events. In 2009, Aug 5th - Aug 9th Event 28: Relentless Boardmasters - Newquay, will be held as part of the World Qualification Series (The Grind) as part of the qualifiers for the honour of competing with the world's best surfers on the ASP World .

Royal Cornwall Show

The Royal Cornwall Agricultural Show, usually called the Cornwall Show, is an agricultural show organised by the The Royal Cornwall Agricultural Association, which takes place at the beginning of June each year, at Wadebridge in North Cornwall. The show was held at Truro between 1827 and 1857, but from then on the venue changed every year. Since 1960 the showground at Wadebridge has been its permanent home. [112] The show lasts for three days and attracts approximately 120,000 visitors annually, making it one of Cornwall's major tourist attractions.

It is not unusual for a senior member of the Royal family to attend at the Show. A familiar sight is Prince Charles who is acknowledged to be a keen supporter of the farming community. Princess Alexandra will attend the 2009 show.

Sport

The Cornwall Rugby Football Union (CRFU) was formed in 1883. It is a union of 39 rugby union clubs which includes every Cornish rugby union club, the open age Cornwall representative side and representative teams at various age groups. Cornwall play most of their home games at Redruth R.F.C. and Camborne RFC but matches have also been played at Penzance & Newlyn and Launceston.

The premier club side in Cornwall are the Cornish Pirates (renamed from Penzance & Newlyn RFC) who play in National Division One. Launceston RUFC ("The Cornish All Blacks") have recently (2007 season) been promoted to the National Division One. Redruth R.F.C. ("The Reds") play in National Division Two and also get good support. Mount's Bay have this season 2007/08 began their campaign in National Division Three, South, leading the league for the entire season they are at season end promoted to National Division Two for the 2008/09 season. The other major Cornish club sides who play in the South West 1, 2 West, Western Counties West and Cornwall & Devon leagues are Bude, Camborne, Falmouth, Hayle, Newquay Hornets Penryn, St. Ives, Saltash, Truro and Wadebridge Camels.

Cornish wrestling is a form of wrestling similar to judo, which has been established in Cornwall for several centuries. The referee is known as a 'stickler', and it is claimed that the popular meaning of the word as a 'pedant' originates from this usage. It is colloquially known as "wrasslin" in Cornish dialect. The Cornish Wrestling Association was formed in 1923 to standardize the rules and to promote Cornish Wrestling throughout Cornwall and indeed Worldwide.

The Cornish Wrestling Association (CWA) still features annually at the Royal Cornwall Agricultural Show. The wrestlers perform demonstrations of their style in the Countryside ring, usually twice a day for each of the three days of the show. The demonstrations feature most of the throws and moves of the Cornish style and also feature demonstration bouts usually with a variety of wrestlers from youngsters, girls, lightweights and heavyweights.

Symbols

Flag

Saint Piran's flag is the flag of Cornwall. According to tradition Saint Piran adopted the white cross on a black field after seeing the molten tin flowing from black ore in his fire. This occurred during his traditional "discovery" of tin in the 6th century thus becoming the patron saint of tin miners. Seeing that tin had been known for 1,500 years before this legendary event others see the pure white "tin" flowing from the black "ore" as a Christian symbol of good triumphing over evil. The Cornish flag may be seen at many cultural events throughout Cornwall and in recent years is flown throughout the area. "Kernow" car stickers using the Cornish flag have also become popular in recent years.

"Cornish" Chough

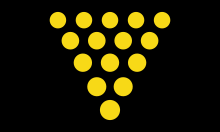

Argent three Cornish Choughs proper two and one

The Red-billed Chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) has a long association with Cornwall, and appears on the Cornish Coat of Arms[113] and the arms of the Duchy of Cornwall. A legend from the county says that King Arthur did not die but was transformed into a Red-billed Chough,[114] and hence killing this bird was unlucky.[115]

The Red-Billed Chough was once found on rocky coastal cliff edges throughout Cornwall but declined during the 19th and 20th centuries, with only about 300 pairs left, mainly in Wales, the Isle of Man and western Scotland. Cornwall was once a stronghold for choughs and they last nested in the country in 1952. Conservation organisations have been working together for a many years in order to secure the return of the chough to Cornwall. In 2001 four wild choughs were spotted in West Cornwall and three took up residence. There was eager anticipation amongst conservationists and during early spring of 2002 a pair of choughs began to nest. By the middle of April the female chough had begun to incubate her eggs making these the first breeding pair of choughs in Cornwall for half a century. The Cornwall Chough Project aims at encouraging the chough to return in greater numbers to Cornwall and safeguarding the future of the bird as a Cornish emblem.[116]

Duchy Symbols

Although "officially" two separate entities[117] [118], many in people in Cornwall informally see the Duchy of Cornwall and (the county of) Cornwall as being the same. The symbols of the Duchy are often adopted by various Cornish entities, the colours "black" and "gold" are also the colours of the Cornwall rugby team.

The arms of the Duke of Cornwall are "sable fifteen bezants Or", that is, a black field bearing fifteen gold discs, representing coins. A small shield bearing these arms appears on the Prince of Wales' heraldic achievement, below the main shield. This symbol is also used by Cornwall County Council to represent Cornwall. These arms were adopted late in the 15th century and are often surmounted by a Prince of Wales coronet, four crosses patée and four fleurs-de-lis with an arch. Supporters are not always used, though the Red-billed Chough and ostrich feathers are sometimes found. Rather than the motto used by the Prince of Wales (i.e., Ich Dien, German for "I serve"), the Duke of Cornwall's Coat of Arms uses the motto "Houmout" (meaning "honour" or "high-spirited") derived from the Black Prince. The banner of the Duchy of Cornwall is simplified, showing the fifteen gold bezants on a black field.

Tartans

In recent years Cornish tartans have gained popularity[weasel words][clarification needed] in Cornwall along with kilts. Although traditionally associated with Highland Scots Gaelic culture the kilt and tartan wearing have come to represent Pan-Celticism[citation needed] and can be seen at most Celtic festivals in the traditional Celtic nations.[citation needed] Cornish tartans are generally considered to be a modern tradition originating in the early to mid 20th Century.Template:Whosaidthis The first modern kilt was plain black, and other patterns followed. Cornish historian L.C.R. Duncombe-Jewell was suggested that plain kilts may have been in use in Cornwall. He discovered carvings showing minstels dressed in what appear to be kilts and playing bagpipes on bench ends at Altarnun church from c1510[119][120] The earliest historical reference to the Cornish kilt is from 1903 when the Cornish delegate to the Celtic Congress, convening at Caernarvon, L Duncombe-Jewell, appeared in a in a wode blue kilt. John T. Koch in his work Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia mentions a black kilt worn by the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry in combat.

The Cornish National Tartan was creasted in 1963 designed by the poet E.E. Morton Nance. Each colour of the tartan has a special significance or meaning. The White Cross on a black background is from Saint Piran's flag. Black and gold were the colours of the ancient Kings of Dumnonia and later the Duchy of Cornwall. Red represents the legs and beak of the Red-Billed Chough, and blue for the sea surrounding Cornwall. [121].

Some Cornish families have registered their own family tartans which are worn at family occasions. [122]- these families include the Christopher, Rosevear and Curnow families.

Boar

The "boar" has a mythological or legendary connection to Arthurian folklore in Conrnwall evidenced by Geoffrey of Monmouth Prophetiae Merlini (Template:Lang-en) "that the race that is oppressed shall prevail in the end, for it will resist the savagery of the invaders. The Boar of Cornwall shall bring relief from these invaders, for it will trample the necks beneath its feet."[123]

Religion

Paganism

It is not known exactly what beliefs the pre-Christian "Celtic" populations of Cornwall may have held. The presence of dolmens, stone circles and menhirs point to a megalithic culture in common with much of Britain, Ireland and Europe. The pre-Roman belief systems of Cornwall may have been similar to the religion of the so-called "Druids" described by Roman commentators- although very little is known about the actual belief systems at hand. Although Dumnonia was anciently under Roman administration it is not known who much Roman religion affected the beliefs of the peoples of the peninsula. Cornish literary and oral traditions tend to begin with the late Roman era and are predominantly Christian or "Celtic Christian". Nevertheless, clues about the ancient pagan beliefs of Cornwall may lie in the folklore and superstitions preserved in the area up until recent times, such as leaving fish for the Bucca to appease the sea spirit, amongst others. In recent times many Neo-Pagan, Neo-Druid and Wiccan groups have become active in Cornwall, working with many of the older traditions of the area and drawing inspiration from the rich megalithic, Arthurian and folklore heritage of the area.

Christianity

The Christian tradition of the Cornish people is as long as the recorded history of Cornwall. Since the Restoration Period the Cornish have been strongly nonconformist in their religious outlook with Methodism and Wesleyanism making strong inroads into Cornwall as well as the presence of the Quaker community. Celtic Christianity was predominant during the first millennium AD and many Cornish saints are commemorated in legends, churches and place names.

Approximately four thousand people from Devon and Cornwall died in the Prayer Book Rebellion in the 1540s, trying to resist the compulsory use of a new English language version of the Book of Common Prayer. Attempts to revert to the Latin version, or to translate the text into Cornish, were suppressed. This failure to produce or sustain a translation of the Bible in Cornish is generally seen as a crucial factor in the demise of the language. An approved version of the New Testament in Cornish was finally published in 2004.[124]

During the Industrial Revolution, Methodism proved to be very popular amongst the working classes in Cornwall. Methodist chapels became important social centres, with church-affiliated groups such as male voice choirs playing a central role in social life. Methodism still plays a large part in the religious life of Cornwall today, although Cornwall has shared in the general post-World War II decline in British religious worship. Cornwall and Gwennap Pit in particular were favourite places of the founder of Methodism, John Wesley.

In 2003, a campaign group was formed called Fry an Spyrys (Template:Lang-en)[125] dedicated to disestablishing the Church of England in Cornwall in favour of an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion; a Church of Cornwall. They appeal to the precedents set when the Anglican Church was disestablished in Wales to form the Church in Wales in 1920 and in Ireland to form the Church of Ireland in 1869. The group's chairman is Dr Garry Tregidga of the Institute of Cornish Studies.

In the late 20th century, and early 21st century has also been a renewed interest in the older forms of Christianity in Cornwall.[citation needed] Cowethas Peran Sans, the Fellowship of St Piran, is one such group promoting Celtic Christianity[126]. The group was founded by Andrew Phillips and membership is open to baptised Christians in good standing in their local community who support the aims of the group. These aims place great emphasis on Cornwall's Celtic Christian heritage:

- To understand and embody the spirituality of the Celtic Saints

- To share this spirituality with others

- To use Cornwall’s ancient Christian holy places again in worship

- To promote Cornwall as a place of Christian spiritual pilgrimage

- To promote the use of the Cornish language in prayer and worship

Institutions and Politics

The Cornish identity is given voice also in the existence of various political and pressure groups. These organisations usually call for greater home rule for Cornwall, recognition of Cornwall as a Duchy and various other human rights issues.[citation needed]

In parliamentary politics, Cornwall is a Liberal Democrat stronghold and in the 2005 General Election, all five members of parliament returned to Westminster were Liberal Democrats.[127] The largest Cornish nationalist party, Mebyon Kernow (Cornish for Sons of Cornwall), fielded candidates in four of the five constituencies and received around 3,500 votes, less than two percent of constituencies' electorate.

The Liberal Democrats have also campaigned on Cornish language issues,[128][129] Cornish national minority issues and for the establishment of a devolved Cornish Assembly[130] and Cornish development agency.[131]

Mebyon Kernow is the only Cornish based political party. The main objective of MK is to establish greater autonomy in Cornwall, through the establishment of a legislative Cornish Assembly. They claim to campaign for all the people of Cornwall with a political programme that offers an alternative to the London-centred parties.

The Cornish branch of the Green Party of England and Wales also campaigns on a manifesto of devolution to Cornwall and Cornish minority issues. In the 2005 general election the Green Party struck a partnership deal with Mebyon Kernow.[132]

Classification

In 1937, Bartholomew published a Map of European Ethnicity prepared by the Edinburgh Institute of Geography which featured the "Celtic Cornish".

More recently, on 12 July 2005, Jim Fitzpatrick MP, an ODPM Parliamentary Under Secretary in the current Labour government, said in the Commons in response to Andrew George MP, a Liberal Democrat representing the St Ives constituency in Cornwall, "I realise that the people of Cornwall consider that they have a separate identity, but that alone does not justify creating an assembly for Cornwall."[133] Phil Woolas MP, Minister for Local Government, indicated the same in his answer to a letter from Mebyon Kernow: "On your point about Cornwall’s desire to control its own future, the Government is very much aware of the strength of feeling about Cornwall’s separate identity and distinctiveness ... The Government recognises that many people in Cornwall consider they have a separate identity."

NGOs such as Eurominority and the Federal Union of European Nationalities also give varying degrees of recognition to a Cornish people.[134][135][136]

Portrayals

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. |

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (June 2009) |

Romantic and literary portrayals of Cornish "Celts"

Early Portrayals

Cornwall and Cornish people have been portrayed in a wide variety of ways. Early travellers to report on Cornwall and her people include John Leland in 1536 and 1542 [137], and Celia Fiennes, in 1698 [138] and the Reverend William Gilpin in 1775.

Romantic Movements

Antiquarian research into the Celtic culture and history of the British Isles gathered pace from the late 17th century, with figures like Owen Jones in Wales and Charles O'Conor in Ireland. Interest in Scottish Gaelic culture also increased during the onset of the Romantic period in the late 18th century, notably with James MacPherson's Ossian achieving fame. Along with the novels of Sir Walter Scott and the poetry and lyrics of Irishman Thomas Moore. It was in this era that throughout Europe, the Romantic movement inspired a great revival of interest in folklore, folk tales, and folk music.During this period Cornwall and the Cornish people were often typified by philanthropic collectors of folklore according to popular notions[weasel words] and stereotypes of the time. In the case of the Cornish, they were perceived to be a "primitive’, dark and wild ‘Celtic’ culture"- an idea of the exotic and wild Celt being typical of the time and often accompanied by nostalgic ideas about Arthurian legends.

19th century- Victorian era

In 1877 Bishop Benson the bishop of the newly created diocese of Cornwall noted with "irritation" that the Cornish by their own admition were "a most peculiar people" to which the Bishop was also in agreement[139]. This sense of difference to England, across the Tamar, has led some anthropologists to see this a concept of diversity largely created by outsiders to Cornwall rather than Cornish people themselves.

In 1867 Francis Harvey a Cornish preacher who had spent time in the then Natal Colony, South Africa complained bitterly of these "false" external depictions of Cornwall with the following comment [6]:

- More monstrous stories of the fearful doings of Cornish wreckers have been

- manufactured by the ‘penny-a-line dreadful accident makers’ in one London low

- newspaper in one winter, than ever really happened in Cornwall since the time

- when Noah's ark was stranded, .... [In contrast] as to the general relative

- moral character of Cornish men, amongst whom the too common infamies of

- inland English counties, such as burglaries, poachings, murders, incendiary

- burnings, treasonable irruptions have not been known, it is indeed a matter

- of just pride to be a Cornishman!

Neverthless these differences and images were also exploited [140] in order to encourage visitors in search of some perceived romantic and spiritual land "lost in time" full of romantic images of smugglers and pirates. Both the folklore and ethnographic studies of the Victorian era were concerned with Celtic populations who were, at the time, often considered to be inferior to the racially superior Germanic Englishman[141]. During the 19th century, such ideas of the Celtic peoples were well noted in depictions of the so-called Celtic peoples of Ireland.[citation needed] The mainstream English popular and scientific communities often presented an array of racial differences between the so-called “Irish Celt” and the “English Saxon”. Victorian ethnology was dominated by English theorists reflecting an ideological necessity of empire in portraying the "Celt" and "Saxon" as racial siblings. [142] Boissevain 1996 maintains [143] that popularly-held stereotypes[weasel words] in turn have led to the creation a "guide book culture", which in Cornwall's case is populated by "pirates, piskies and sweeping landscapes filled with exotic Celts"[144]

Thomas Hardy, whose wife Emma Gifford was Cornish, was a romantic novelist who portrayed the West Country in his fictitious "Wessex" as wild, remote, exotic and otherwordly. Although all of Hardy's cultural references are not specifically related to Cornwall, the idea of something wild, exotic and oldworldly in relation to the greater West Country area is certainly to be found in many of his works. In The Return of the Native Hardy calls upon ancient imagery and in his preface In the preface to the novel described Egdon Heath saying "It is pleasant to dream that some spot in the extensive tract whose south-western quarter is here described may be the heath of that traditionary King of Wessex - Lear" In the first chapter of the novel Hardy's opening pages describe the people who live around Egdon Heath. The people are more pagan than Christian in their attitudes and Hardy mentions the pagan custom of lighting bonfires to ward off the oncoming winter. Paganism and references to a "Celtic" otherworld recurr throughout The Return of the Native. Rainbarrow is an artificial burial mound raised by primordial Celtic tribes and the main character Eustacia Vye is described as "Promethean" and pagan "Queen of the Night"- it is on the Rainbarrow that she first encounters Clym Yeobright as a Celtic urn has been discovered.

Thomas Hardy himself had worked as an architect on St. Juliot's church, near Boscastle in Cornwall. He married his Cornish wife in 1874 and she died in 1912. Hardy wrote several poems about their relationship in the years after her death and, in typical Hardy style, altered some place names, although others remain unchanged. St. Juliot and Beeny Cliff are real locations in the area of Boscastle whereas Castle Boterel refers to Boscastle itself. Thomas Hardy drew on Romantic “Celtic” imagery himself by using the name Lyonesse and referring to the mythical land of ancient Cornwall exemplified in his poem "When I Set Out From Lyonnesse”.

The Romantic idea of Cornwall was that of a land where time had stopped, a place in which ancient superstitions had managed to outlive the impact of the Romans, English] and Normans. [145]. In confirmation of this the 1893 Ethnographic Survey of the British Isles studied the inhabitants and folklore of Cornwall in thirty-five various locations throughout the area believing that Cornwall’s isolation would provide them with an example of a "remarkably uncorrupted race of ‘primitive’ people" [146] In 1877 Bishop Benson also noted that the Cornish were "a most peculiar people". This sense of difference to England, across the Tamar, has led some anthropologists to see this as a concept of diversity largely created by outsiders to Cornwall and note necessarily Cornish people themselves. Furthermore this difference was used [147] to encourage Victorian visitors who were in search of some perceived romantic and spiritual land lost in time.

20th century

Out of the Romantic movements and renewed interest in Celtic folklore during the 19th century sprang the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, founded in 1924, whose main aim was to preserve “all those ancient things that make the spirit of Cornwall — its traditions, its old words and ways, and what remains to it of its Celtic language and nationality"- confirming again the sense of “otherness” or difference. The Gorseth Kernow (Gorsedd of Cornwall) was also founded in 1928 at Boscawen-Un by Henry Jenner, one of the leading early revivalists of the Cornish language. Jenner, along with twelve others were "initiated" by the Archdruid of Wales. Later in the 20th century this romantic tradition of Cornwall and Cornish people was yet again taken up by writers and artists, examples including the Poldark series of novels written by Winston Graham in the period 1945-2002 and the many Cornish-themed works of Daphne du Maurier.

In more recent times the works of the late Nick Darke, although rooted in Cornish society and culture and reflecting historical subjects such as tin mining and fishing, departed from the more traditional and romantic view of the Cornish people and prompted a review in the in The Financial Times, "Darke gives shape to a Cornish idenitity that feels vital and real and has nothing to do with clay pipes and clotted cream". [148]. Darke worked regularly with the Cornish theatre company Kneehigh Theatre. One of his last works, the documentary The Wrecking Season (2004) which he wrote and narrated, charts the lives of Cornish beachcombers, of which he himself was one having moved permanently back home to Porthcothan in 1990.

Negative portrayals of the Cornish

Some people in Cornwall feel that they are often the victims of stereotyping, all too often negative. Negative stereotypes of the Cornish may perhaps be divided into negative or stereotypical portrayals of West Country people in general and those stereotypes more specific toCornish people alone. The issue of stereotyping and how people are viewed by others is complex in itself. [149]. In Cornwall the feeling is strong enough however to promt Andrew George M.P. to make the following comment "However, I know that whilst, sadly for the Cornish, I am the living embodiment of some of the worst racist stereotypes we too often have to endurethe truth is that the Cornish are just like any other members of the human race - bright, able and, given the opportunity, capable of great success." [150] For at least half a century Cornwall has relied heavily on external tourism in order to sustain the local economy and so many stereotypes of Cornish people are based on ideas of fishermen, pirates, rustic people, rural backwaters and many stereotypes that many rural communities throughout the United Kingdom probably encounter in some form or another. Within the broader spectrum of the West Country it has been remarked in Bristol that "The people of the South West have long endured the cultural stereotype of 'ooh arr'ing carrot crunching yokels, and Bristol in particular has fought hard to shake this image off".[151]

Early negative portrayals of the Cornish

- c1120: William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120, writing of Athelstan's actions in 927 driving the Cornish from much of Devon, said that "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race"

- 1652: Roger Williams, a Puritan preacher, complained that "we have Indians ... in Cornwall, Indians in Wales, Indians in Ireland".[152][153]

In the period 1497-1651 the Cornish had risen up against the English Crown during the Cornish Rebellion of 1497, with the defeat of the Cornish forces severe monetary penalties were inflicted on Cornwall and resulted in empoverishing sections of the community for many years to come. Prisoners were sold into slavery and estates were seized and handed to more "loyal" subjects. About half a century later the Cornish rose again in the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549 along with sections of the Devon community. The rebellion failed and in total over 5,500 people were killed in the conflict. Further orders were issued on behalf of the king by the Lord Protector the Duke of Somerset, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer English and mercenary forces then moved throughout Devon and into Cornwall and executed or killed many people before the bloodshed finally ceased. Proposals to translate the Book of Common Prayer into Cornish were also suppressed. Research has suggested that before the rebellion the Cornish language had strengthened and more concessions had been made to Cornwall as a "nation", in relation to which anti-English sentiment had been growing stronger, providing additional impetus for the rebellion.[154][page needed] This anti-English sentiment was picked up on by the French ambassador in London, Gaspard de Coligny Chatillon when he wrote in 1538 that "The kingdom of England is by no means a united whole, for it also contains Wales and Cornwall, natural enemies of the rest of England, and speaking a [different] language."

During the English Civil Wars, Cornwall was almost unanimously Royalist and anti-Parliamentarian. No other area of Great Britain appeared so unanimously pro-Charles I.[citation needed] One of the reasons that Cornwall was a Royalist enclave in the generally Parliamentarian south-west was that Cornwall's rights and privileges were tied up with the royal Duchy and Stannaries. The Cornish saw the Civil War as a fight between England and Cornwall as much as a conflict between King and Parliament. With the defeat of the Royalists the Cornish had again not endeared themselves to Parliament and the English "establishment".

Modern negative portrayals of the Cornish

- 1999: Giles Coren, The Times (London), Friday August 13, 1999. In an article entitled A Truro lass can eclipse me any day[155], Coren wrote "I hate the Cornish. I'm glad that nobody went to the eclipse, and that those who did couldn't see it. I hate their poxy language which they make such a fuss about, and their stupid morris dancing clothes. And I hate their fancy foreign food - like clotted cream - which makes the place stink, and I hate their fatuous demands to be treated as a nation." The article caused offence and was quoted by Angarrack in Breaking the Chains[156] as offensive to the Cornish people. Further on the article Coren states he wishes to become a serious writer "...And you can't unless you occasionally tempt people to wonder whether you are a loony racist", thereby indicating the article is a parody. Nevertheless the opening quote has been seen by many as offensive to Cornish people and is quoted also in Working Papers 21: Cornish: Language and Legislation by Dr. Davyth A. Hicks at Mercator Linguisitc Rights and Legislation.[157]

- 1999: In the Western Morning News, 7 September, A.A. Gill, a Sunday Times journalist described the Cornish as "mean" and "stunted trogldytes" who were "easily bribed". When this was challenged, Gill's editor shrugged off complaint as "the basic tools of a jobbing humorist". [158]

- 2000: Petronella Wyatt in The Spectator, 24 June 2000 wrote an article called Cornish Loathing, complaining that "The Cornish loathe everything but sloth. They heartily dislike the English whom they regard as foreigners. The Cornish have no desire to work possessing less ambition to better themselves than a rich woman's poodle, the rich woman being the E.U. which keeps them going by way of outrageous farm subsidies... [but] I love Cornwall (because) it must be the only seaside destination in Western Europe which has avoided Disneyfication.[159][160][161]

- 2000: Carlton Television broadcast a programme called The Most Deadly Sin of Pride, on Friday, 7 July (22:30). The sin of pride was represented by several subjects including Cornish rugby supporters, Cornish Bards, Cornish Romanies, and French Can-Can dancers. Each of these was intercut with black and white archive footage from the 1930s, including Hitler at the Nuremberg Rally.[162]

- 2007: Western Daily Press (Bristol) 28 November 2007 - South West Columnist of the Year, Chris Rundle wrote an article entitled "Saints alive! Pasty eaters demand new bank holiday" and goes on to describe his contempt for the "pasty eaters", their Cornish indigenous language, Saint Piran's day and describes Cornwall as "one of the most depressing places one can find oneself, with an economy barely more buoyant than that of Romania". The article begins with the question "When is someone going to put the Cornish in their place?" and describes the Cornish language as sounding "like someone speaking Urdu with a mouth full of nails". [163][164]

- 2007: Leo Benedictus, in The Guardian in January, listed the following reasons not to move to Cornwall:- "Niche nationalism, Darkie Day, everyone's a Lib Dem, the missing generation, terrible football and cider."[165]

- June 2008: Students from Imperial College London were condemned for branding people from Cornwall as "inbreds" by Kerrier District Councillor Gragam Hicks after he discovered a webiste in which was quoted, "The Royal School of Mines Hockey Club follows in a long line of RSM sporting prowess but most of all its about fun, drinking and beating the pulp out of little Cornish inbreds who like to call themselves miners. The comments were removed from the website promptly." [166]

- Mebyon Kernow Novemner 2008: On the Mebyon Kernow blogspot Dick Cole reported that in response to Peter Tatchell's article on the “Comment is Free” section on The Guardian newspaper’s website [167], entitled “Self-rule for Cornwall”. Dick Cole reports that over 1,500 comments were received and that he was "disappointed" "to see so many negative, inaccurate and offensive posts". One such post is quoted as follows: “The Cornish wurzels [168] deserve nothing but contempt and should be sent back to where they belong, labouring down the bottom of a deep hole, the deeper the better … heads full of pasties and rotten clotted cream … inbreds all.” Dick Cole went on to say that Peter Tatchell himself had described many of the comments as “anti-Cornish vitriol” and “bigoted stereotyped anti-Cornish posts”. In fairness Dick Cole also pointed out that some of the pro-Cornish comments had been "unwise" [169].

See also

- Anglo-Cornish dialect

- List of topics related to Cornwall

- List of people from Cornwall

- Cornish American

- Grass Valley, California - Large Cornish-descent community.

- Tangier Island, Virginia - Cornish fishing settlement.

References

- ^ Cornwall Council - Cornwall in Context

- ^ ETHNICITY, NATIONAL IDENTITY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION IN THE 2001 CENSUS

- ^ a b c Canadian 2006 Census Data

- ^ Cornish Communities Programme - University of Exeter

- ^ London School of Economics - 2006 Local government abstracts

- ^ Payton, Philip: Cornwall – a History. ISBN 1-904880-05-3

- ^ BBC - Immigration and Emigration - I'm Alright Jack

- ^ Nesbit, Robert C. (1989). Wisconsin: A History. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-10804-X.

- ^ Grass Valley's St Pirans Day Celebration - DowntownGrassValley.com

- ^ The Cornish Overseas. Philip Payton. Cornwall Editions Limited. April 2005. ISBN 978-1904880042.

- ^ Plummer, Charles. (1922). Betha Naem nErenn

- ^ Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford

- ^ Carter, Eileen. (2001). In the Shadow of St Piran

- ^ Doble, G. H. (1965). The Saints of Cornwall. Dean & Chapter of Truro.

- ^ Ford, David Nash. (2001). Early British Kingdoms: St. Piran, Abbot of Lanpiran. Nash Ford Publishing.

- ^ Loth, J. (1930). 'Quelques victimes de l'hagio-onomastique en Cornwall: saint Peran, saint Keverne, saint Achebran' in Mémoires de la Société d'Histoire et d'Archéologie de Bretagne.

- ^ Tomlin, E. W. F. (1982). In Search of St Piran

- ^ A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles, Cristian Capelli et al. in Current Biology, Volume 13, Issue 11, Pages 979-984 (2003). Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- ^ Channel 4 TV April 2007 - "Faces of Britain" identifying the Cornish Celtic gene

- ^ Sykes, Bryan (2006). Blood of the Isles : exploring the genetic roots of our tribal history. London: Bantam. ISBN 0593056523.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). The origins of the British : a genetic detective story : the surprising roots of the English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 9780786718900.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ http://www.eupedia.com/europe/origins_haplogroups_europe.shtml#R1b

- ^ Halliday, p. 51.

- ^ Halliday, p. 52.

- ^ Stoyle, Mark: West Britons -Cornish Identities and the Early Modern British State ISBN 0-85989-687-0.

- ^ http://www.megalithics.com/england/chun/chunmain.htm

- ^ http://www.historic-cornwall.org.uk/a2m/neolithic/chambered_tomb/chun_quoit/chun_quoit.htm

- ^ http://www.stone-circles.org.uk/stone/chun.htm

- ^ http://www.cornwalltour.co.uk/chun_quoit.htm

- ^ Burl, Aubrey (2000). The stone circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. Yale University Press. Ch.9.

- ^ Cope, Julian (1998). The Modern Antiquarian: A Pre-Millennial Odyssey Through Megalithic Britain. HarperCollins p164

- ^ Weatherhill, Craig (2000). Cornovia: Ancient sites of Cornwall and Scilly. Cornwall Books

- ^ Weatherhill, Craig (1995). Cornish Place Names & Language. Sigma Leisure

- ^ http://www.roman-britain.org/places/ictis.htm

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2002). The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek: The Man Who Discovered Britain (Revised ed.). Walker & Co, Penguin

- ^ Ellis, P. B.(1993). Celt and Saxon. London: Constable and Co.

- ^ Payton, P. J. (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

- ^ Philip Payton (1996) A History of Cornwall; p. 82

- ^ Payton, P. J. (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

- ^ 1497 Cornish battle at Deptford Bridge, London

- ^ Channel 4 - Perkin Warbeck - The great pretender

- ^ http://www.cornwallgb.com/cornwall_england_history.html Thomas Flamank 1497

- ^ http://www.st-keverne.com/church/an_gof.html Mychal Josef an Gof "The Smith"

- ^ http://www.fantompowa.net/Flame/cornish_rebels_1497.html The Battle of Deptford Bridge (Blackheath) 1497

- ^ http://www.cornishworldmagazine.co.uk/history/angof.htm The Cornish Rebellion

- ^ http://www.trelawnysarmy.org.uk/ta/tatrelny.html "A name perpetual and a fame permanent and immortal"

- ^ http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/Documents/the_black_heath_rebellion.htm The Black Heath Rebellion, 16 June 1497

- ^ http://kris.rootschat.net/flamankfamily.html Thomas Flamank

- ^ http://www.cornwall-calling.co.uk/famous-cornish-people/michael-an-gof.htm Michael An Gof, the Cornish Blacksmith

- ^ http://cornishworld.net/HISTORYMAKERS/AnGof.htm Michael Joseph

- ^ Philip Payton, Cornwall - A History, 1996

- ^ http://mb-soft.com/believe/text/methodis.htm

- ^ http://www.methodistrecorder.co.uk/cornwall.htm

- ^ http://www.cornwall.gov.uk/default.aspx

- ^ http://www.exeter.ac.uk/cornwall/academic_departments/huss/ics/documents/Chapter9.pdf

- ^ http://homepage.mac.com/craigadams1/WESPERF/SECTN17.html

- ^ http://www.cornish-methodists.org/

- ^ Duchy of Cornwall history relating to the Cornish Foreshore Case

- ^ Philip Payton. (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

- ^ Template:UK-SLD

- ^ Cornwall Submarine Mines Act 1858

- ^ "The Cornish Question" by Mark Sandford - Constitutional Unit, School of Public Policy, University College London 2002

- ^ Cornish Fighting Fund

- ^ http://www.cornishstudies.com/index.php?q=node/15

- ^ http://west-penwith.org.uk/bounty.htm

- ^ http://west-penwith.org.uk/ohio1.htm

- ^ http://www.chycor.co.uk/murdoch-house/connect1.htm

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/immig_emig/england/cornwall/article_1.shtml

- ^ http://www.calstock.info/census/people_emigrants.htm

- ^ http://www.swo.org.uk/

- ^ Rob, Andew, 'David Penhaligon' in 'Parliamentary Profiles L-R' (1985) (Parliamentary Profiles Service, London

- ^ Penhaligon Annette, 'Penhaligon' (1989) Bloomsbury, London

- ^ http://download.swdebates.info/file.asp?File=/general-1/provocations/Cornwall+and+an+ageing+population+-+Julia+Goldsworthy.pdf

- ^ http://www.swdebates.info/debateslive/blog/viewblogentry.asp?id=64

- ^ http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/cornishcom/documents/PopulationchangeinCornwall1951-2001.pdf

- ^ Cornwall timeline

- ^ Various authors: Cornish Studies series, ed. Philip Payton ISBN 0-85989-771-0.

- ^ BBC News 11th December 2001 [1]

- ^ [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/2410383.stm BBC News November 2002 - Cornish gains official recognition from the Government

- ^ Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly from Census 2001: National Statistics Online, Office for National Statistcs. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- ^ Appendix I: Sample Profile (downloadable '.doc' file) from QUALITY OF LIFE IN CORNWALL: Summary Report (2004), by Cornwall County Council Research and Information Unit. Retrieved 16 July 2006.

- ^ Morgan Stanley survey shows that 44% identify as Cornish rather than English or British

- ^ Calls for Cornish identity to be clearly recorded on 2011 Census

- ^ WCORWhite - Cornish ONS Census codes

- ^ [2] from The London School of Economics and Political Science website.

- ^ Cornish ethnicity data from the 2001 Census

- ^ Cornish demand tick box for 2011 Census

- ^ Mebyon Kernow support 2011 Census Cornish ethnicity tick box

- ^ "Cornish" was one of the most requested ethnic groups for the 2011 census

- ^ Peggy Combellack’s conundrum: locating the Cornish identity

- ^ Tre, Pol and Pen - The Cornish Family by Bernard Deacon

- ^ Cornish surnames - By Tre, Pol and Pen shall ye know all Cornishmen

- ^ http://www.cornwalls.co.uk/history/industrial/diaspora.htm>

- ^ Cousin Jack: BBC - Legacies - Immigration and Emigration - England - Cornwall. Website. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- ^ http://www.londoncornish.co.uk/southafricas.html

- ^ http://www.cornwalls.co.uk/history/industrial/diaspora.htm

- ^ http://www.lcrfc.co.uk/index.php

- ^ A Glossary of the Cornish Dialect - K. C. Phillipps 1993- ISBN 0907018912

- ^ Cornish dialect dictionary

- ^ bally.fortunecity.com/sligo/172/language.html

- ^ Phillipps, K.C., A Glossary of the Cornish Dialect(1993):Tabb House

- ^ http://www.an-daras.com/music/m_dialect_editor.htm

- ^ http://www.an-daras.com/music/m_dialect_tombawcockeve.htm

- ^ BBC News - June 2005 - Cash boost for Cornish language

- ^ Suppression of Cornish identity and language

- ^ Moberly, Greg (2008-03-10). "Flight of the pasty". The Union. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Williamson, George C. Curious Survivals ISBN 0766144690; p. 148.

- ^ Caput XV: De mensibus Anglorum from De mensibus Anglorum. Available online: [3]

- ^ http://englishheathenism.homestead.com/folkcustoms.html

- ^ BBC - Cornwall - About Cornwall - Obby Oss Day

- ^ Midsummer’s Eve Bonfire, at Reduth

- ^ Royal Cornwall Agricultural Association

- ^ "The Cornwall County Council Coat of Arms". Cornwall County Council. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Newlyn, Lucy (2005). Chatter of Choughs: An Anthology Celebrating the Return of Cornwall’s Legendary Bird. Hypatia Publications. p. 31. ISBN 1872229492.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 97. ISBN 0-7204-8021-3.

- ^ bird.http://www.cornwall.gov.uk/default.aspx?page=14166

- ^ http://www.duchyofcornwall.org/ Official Website of the Duchy of Cornwall

- ^ http://duchyofcornwall.eu/ History of the Duchy of Cornwall

- ^ Tanner Marcus (2006). The The Last of the Celts. Yale University Press. p. 241. ISBN 0300115350.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Altarnun church

- ^ Cornish Tartan from the Cornwall County Council website

- ^ [http://www.houseoftartan.com/scottish/dir2.asp?secid=80&subsecid=1127 House of Tartan: Cornish]

- ^ Geoffrey Of Monmouth - The Prophecies of Merlin

- ^ The Cornish New Testament was published by the Cornish Language Board on 13 August 2004.

- ^ Fry an Spyrys: The campaign for self-government for the churches of Cornwall. Website. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- ^ http://www.peran.org.uk/index.htm Fellowship of St Piran

- ^ General Election 2005, Results in Full Map of constituencies from Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 15 July 2005.

- ^ Cornish gains official recognition: BBC News, 6 November 2002. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- ^ Local MP swears oath in Cornish BBC News, 12 May, 2005. Retrieved 15 July 2006.