Pristina: Difference between revisions

PjeterPeter (talk | contribs) |

m Reverted edits by PjeterPeter (talk) to last revision by Region190 (HG) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

|mapsize = |

|mapsize = |

||

|map_caption = |

|map_caption = |

||

|pushpin_map = |

|pushpin_map = Serbia |

||

|pushpin_label_position = above |

|pushpin_label_position = above |

||

|pushpin_mapsize = |

|pushpin_mapsize = |

||

|pushpin_map_caption = Location in |

|pushpin_map_caption = Location in Serbia |

||

<!-- Location ------------------> |

<!-- Location ------------------> |

||

|coordinates_region = RS-KM |

|coordinates_region = RS-KM |

||

Revision as of 13:34, 10 November 2013

Pristina | |

|---|---|

Municipality and City | |

| Prishtina Prishtina / Prishtinë Приштина / Priština | |

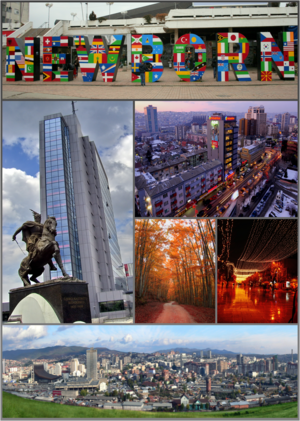

From top (left to right): the Newborn monument, the Kosovo Goverment Building and the Skanderbeg monument, modern Pristina, the Gërmia Park, Mother Teresa Square, and a panoramic view of the city. | |

| Country | Kosovo[a] |

| District | District of Pristina |

| Area | |

| • Municipality and City | 854 km2 (330 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 652 m (2,139 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipality and City | 198,214 |

| • Density | 230/km2 (600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 465,186 (2,011 Census) |

| Demonym(s) | Prishtinas Prishtinali (local) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381 38 |

| Website | Municipality of Pristina Template:Sq icon |

Pristina, also spelled Prishtina[1][2] (Albanian: Prishtinë or ; [Приштина or Priština] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help); Turkish: Priştine), is the capital and largest city of Kosovo.[a] It is the administrative center of the homonymous municipality and district.

Preliminary results of the 2011 census put the population of Pristina at 198,000.[3] The city has a majority Albanian population, alongside other smaller communities including Bosniaks, Roma and others. It is the administrative, educational, and cultural center of Kosovo. The city is home to the Universiteti i Prishtinës and is served by the Pristina International Airport.

Name

The name of the city is derived from a Slavic form *Prišьčь, a possessive adjective from the personal name *Prišьkъ, (preserved in the Kajkavian surname Prišek, in the Old Polish personal name Przyszek, and in the Polish surname Przyszek) and the derivational suffix -ina 'belonging to X and his kin'.[citation needed] The name is most likely a patronymic of the personal name *Prišь, preserved as a surname in Polish Przysz and Sorbian Priš, a hypocoristic of the Slavic personal name Pribyslavъ.[4] A false etymology[citation needed] connects the name Priština with Serbo-Croatian prišt (пришт), meaning 'ulcer' or 'tumour', referring to its 'boiling'.[5] However, this explanation cannot be correct, as Slavic place names ending in -ina corresponding to an adjective and/or name of an inhabitant lacking this suffix are built from personal names or denote a person and never derive, in these conditions, from common nouns (SNOJ 2007: loc. cit.). The inhabitants of this city call themselves Prishtinali in local Gheg Albanian or Prištevci (Приштевци) in the local Serbian dialect.

Geography

Pristina is located at the geographical coordinates 42° 40' 0" North and 21° 10' 0" East and covers 572 square kilometres (221 sq mi). It lies in the north-eastern part of Kosovo close to the Goljak mountains. From Pristina there is a good view of the Šar Mountains which lie several kilometres away in the south of Kosovo. Pristina is located beside two large towns, Obilić and Kosovo Polje. In fact Pristina has grown so much these past years that it has connected with Kosovo Polje. Lake Badovac is just a few kilometres to the south of the city.

There is no river passing through the city of Pristina now but there was one that passed through the center. The river flows through underground tunnels and is let out into the surface when it passes the city. The reason for covering the river was because the river passed by the local market and everyone dumped their waste there. This caused an awful smell and the river had to be covered.[citation needed]

The river now only flows through Pristina's suburbs in the north and in the south.

Climate

Pristina has an oceanic climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification), with continental influences. The city features warm summers and relatively cold, often snowy winters.

| Climate data for Pristina | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.3 (90.1) |

36.3 (97.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.1 (39.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.9 (23.2) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.2 (−17.0) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.9 (1.53) |

36.1 (1.42) |

38.8 (1.53) |

48.8 (1.92) |

68.2 (2.69) |

60.3 (2.37) |

51.6 (2.03) |

44.0 (1.73) |

42.1 (1.66) |

45.4 (1.79) |

68.2 (2.69) |

55.5 (2.19) |

597.9 (23.54) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.6 | 12.3 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 12.3 | 14.5 | 133.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 77 | 70 | 65 | 67 | 67 | 63 | 62 | 68 | 74 | 80 | 83 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.8 | 96.0 | 143.0 | 184.0 | 227.9 | 246.3 | 299.3 | 289.6 | 225.8 | 173.5 | 96.9 | 70.2 | 2,123.3 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[6] | |||||||||||||

Panorama

History

Early history

The area in and around Pristina has been inhabited for nearly 10,000 years.[7] Early Neolithic findings were discovered dating as far back as the 8th century BC, in the areas surrounding Pristina, i.e.: Matiçan, Gračanica and Ulpiana.[7][8] The main finding was a 6,000 year old terracotta figure of a 'Goddess on the Throne'

The early inhabitants of Pristina were the Dardani, an Illyrian tribe that occupied Dardania.[9][10] In the 4th century BC, Bardyllis succeeded in bringing various Dardani tribes together establishing the Dardanian Kingdom.[11][12][13] After Roman conquest of Illyria at 168 BC, Romans colonized and founded several cities in the region of Dardania.[14]

During the Roman period, Pristina was part of the province of Dardania and Ulpiana was considered one of the most important Roman cities in the Balkans. In the 2nd century AD, Ulpiana became a Roman municipium. The city suffered tremendous damage from an earthquake in AD 518.[15] The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I decided to rebuild the city in great splendor and renamed it Justiniana Secunda but with the arrival of Slav tribes in the 6th century the city again fell into disrepair.[15]

Medieval period

The first historical record mentioning Pristina dates back to 1342 when the Byzantine Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos described Pristina as a 'village'.[7] In the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, Pristina developed as an important mining and trading center thanks to its proximity to the rich mining town of Novo Brdo, and due to its position of the Balkan trade routes. The old town stretching out between the Vellusha and Prishtevka rivers which are both covered over today, became an important crafts and trade center. Pristina was famous for its annual trade fairs (Panair)[7] and its goat hide and goat hair articles. Around 50 different crafts were practiced from tanning to leather dying, belt making and silk weaving, as well as crafts related to the military – armorers, smiths, and saddle makers. As early as 1485, Pristina artisans also started producing gunpowder. Trade was thriving and there was a growing colony of Ragusan traders (from modern day Dubrovnik) providing the link between Pristina's craftsmen and the outside world.[7] The first mosque was constructed in the late 14th century while still under Serbian rule.[7]

Initial Ottoman period

In the early Ottoman era, Islam was an urban phenomenon and only spread slowly with increasing urbanization. The travel writer Evliya Celebi, visiting Pristina in the 1660s was impressed with its fine gardens and vineyards.[7] In those years, Pristina was part of the Vıçıtırın Sanjak and its 2,000 families enjoyed the peace and stability of the Ottoman era. Economic life was controlled by the guild system (esnafs) with the tanners' and bakers' guild controlling prices, limiting unfair competition and acting as banks for their members. Religious life was dominated by religious charitable organizations often building mosques or fountains and providing charity to the poor.

Austrian-Turkish War

During the Austrian-Turkish War in the late 17th century, Pristina citizens under the leadership of the Catholic Albanian priest Pjetër Bogdani pledged loyalty to the Austrian army and supplied troops. He contributed a force of 6,000 Albanian soldiers to the Austrian army which had arrived in Pristina. Under Austrian occupation, the Fatih Mosque (Mbretit Mosque) was briefly converted to a Jesuit church.[7]

Following the Austrian defeat in January 1690, Pristina's inhabitants were left at the mercy of Ottoman and Tatar troops who took revenge against the local population as punishment for their co-operation with the Austrians. A French officer traveling to Pristina noted soon afterwards that "Pristina looked impressive from a distance but close up it is a mass of muddy streets and houses made of earth".[7]

Declining Ottoman era and Balkan War

The year 1874 marked a turning point. That year the railway between Salonika and Mitroviça started operations and the seat of the vilayet of Prizren was relocated to Pristina. This privileged position as capital of the Ottoman vilayet lasted only for a short while. from January until August 1912, Pristina was liberated from Ottoman rule by Albanian rebel forces led by Hasan Prishtina.[16] However, The Kingdom of Serbia opposed the plan for a Greater Albania, preferring a partition of the European territory of the Ottoman Empire among the four Balkan allies.[17] On October 22, 1912, Serb forces took Pristina. However, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the first Balkan War, occupied Kosovo in 1915 and took Pristina under Bulgarian occupation.[18] In late October 1918, the 11th French colonial division took over Pristina and returned Pristina back to what then became the 'First Yugoslavia' on the 1st of December 1918.[18] On September 1920, the decree of the colonization of the new southern lands' facilitated the takeover by Serb colonists of large Ottoman estates in Pristina and land seized from Albanians.[18] The interwar period saw the first exodus of Albanian and Turkish speaking population.[7][18]

World War II

On the 17th of April 1941, Yugoslavia surrendered unconditionally to axis forces. On June 29, Benito Mussolini proclaims greater Albania, with most of Kosovo under Italian occupation was united with Albania. There ensued mass killings of Serbs, in particular colonialists, and an exodus of tens of thousands of Serbs.[19] [20] After the capitulation of Italy, Nazi Germany took control of Pristina. Under German occupation in the 1940s, a large part of Pristina's already small Jewish community was deported. The few surviving families eventually left for Israel in 1949.[7] As a result of these wars and forced migration, Pristina's population dropped to 9,631 inhabitants.[7]

Pristina after World War II

The communist decision to make Pristina the capital of Kosovo in 1947 ushered a period of rapid development and outright destruction. The Yugoslav communist slogan at the time was uništi stari graditi novi (destroy the old, build the new). In a misguided effort to modernize the town, communists set out to destroy the Ottoman bazaar and large parts of the historic center, including mosques, catholic churches and Ottoman houses.[7] A second agreement signed between Yugoslavia and Turkey in 1953 led to the exodus of several hundreds more Albanian families from Pristina. They left behind their homes, properties and businesses.[7] However, this policy changed under the new constitution ratified in 1974. Few of the Ottoman town houses survived the communists' modernization drive, with the exception of those that were nationalized like today's Emin Gjiku Museum or the building of the Institute for the Protection of Monuments.[citation needed]

As capital city and seat of the government, Pristina creamed off a large share of Yugoslav development funds channeled into Kosovo. As a result the city's population and its economy changed rapidly. In 1966, Pristina had few paved roads, the old town houses had running water and Cholera was still a problem. Prizren continued to be the largest town in Kosovo. Massive investments in state institutions like the newly founded University of Pristina, the construction of new high-rise socialist apartment blocks and a new industrial zone on the outskirts of Pristina attracted large number of internal migrants. This ended a long period when the institution had been run as an outpost of Belgrade University and gave a major boost to Albanian-language education and culture in Kosovo. The Albanians were also allowed to use the Albanian flag.[citation needed]

Within a decade, Pristina nearly doubled its population from about 69,514 in 1971 to 109,208 in 1981.[7] This golden age of externally financed rapid growth was cut short by Yugoslavia's economic collapse and the 1981 student revolts. Pristina, like the rest of Kosovo slid into a deepening economic and social crisis. The year 1989 saw the revocation of Kosovo's autonomy under Milošević, the rise of Serb nationalism and mass dismissal of ethnic Albanians.[7]

Pristina in the Kosovo War and afterwards

Following the reduction of Kosovo's autonomy by Serbian President Slobodan Milošević in 1989, a harshly repressive regime was imposed throughout Kosovo by the Yugoslav government with Albanians largely being purged from state industries and institutions.[7] The LDK's role meant, that when the Kosovo Liberation Army began to attack Serbian and Yugoslav forces from 1996 onwards, Pristina remained largely calm until the outbreak of the Kosovo War in March 1999. Prishtina was spared large scale destruction compared to towns like Đakovica or Peć that suffered heavily at the hands of Serbian forces. For their strategic importance, however, a number of military targets were hit in Pristina during NATO's aerial campaign, including the post office, police headquarters and army barracks (today's Adem Jashari garrison on the road to Kosovo Polje).[citation needed]

Widespread violence broke out in Pristina. Serbian and Yugoslav forces shelled several districts and, in conjunction with paramilitaries, conducted large-scale expulsions of ethnic Albanians accompanied by widespread looting and destruction of Albanian properties. Many of those expelled were directed onto trains apparently brought to Pristina's main station for the express purpose of deporting them to the border of the Republic of Macedonia, where they were forced into exile.[21]

On, or about, 1 April 1999, Serbian police went to the homes of Kosovo Albanians in the city of Pristina/Prishtinë and forced the residents to leave in a matter of minutes. During the course of Operation Horseshoe, a number of people were killed. Many of those forced from their homes went directly to the train station, while others sought shelter in nearby neighbourhoods. Hundreds of ethnic Albanians, guided by Serb police at all the intersections, gathered at the train station and then were loaded onto overcrowded trains or buses after a long wait where no food or water was provided. Those on the trains went as far as Đeneral Janković, a village near the Macedonian border. During the train ride many people had their identification papers taken from them.[22]

— War Crimes Indictment against Milošević and others

The majority Albanian population fled the town in large numbers to escape Serb policy and paramilitary units. The first NATO troops to enter Pristina in early June 1999 were the British, although to NATO's diplomatic embarrassment Russian troops arrived first at the airport. Apartments were occupied illegally and the Roma quarters behind the city park was torched. Several strategic targets in Pristina were attacked by NATO during the war, but serious physical damage appears to have largely been restricted to a few specific neighbourhoods shelled by Yugoslav security forces. At the end of the war, almost all of the city's 45,000 Serb inhabitants fled from Kosovo and today only several dozen remain within the city.[23]

As a capital city and seat of the UN administration (UNMIK), Pristina has benefited greatly from a high concentration of international staff with disposable income and international organizations with sizable budgets. The injection of reconstruction funds oth from donors, international organizations and the Albanian diaspora has fueled an unrivaled, yet short-lived, economic boom. A plethora of new cafes, restaurants and private businesses opened to cater for new (and international) demand with the beginning of a new era for Pristina.[citation needed]

Economy

The number of registered businesses in Pristina is currently at 8,725, with a total of 75,089 employees[citation needed]. The exact number of businesses is unknown because not all are registered. Since independence the Mayor of Pristina, Isa Mustafa has built many new roads in Pristina. Also he has plans to construct a ring road around the city.[24] The national government is taking part in modernising the roadways as well, building motorways to Uroševac and other cities[citation needed]. An Albanian millionaire in Croatia is building the largest building in the Balkans with a projected height of up to 262 metres (860 ft) and capacity to hold 20,000 people. The cost for this is 400 million Euro.[25] The Lakriste area is designated by Municipality as high-rise area with many complex building. The buildings such as ENK, World Trade Centre, Hysi and AXIS towers are being constructed in an area which previously served as an industrial zone.[26]

Turkey's Limak Holding and French firm Aéroport de Lyon won the concession tender for Pristina International Airport. Two companies pledged investment of 140 million euros by 2012.[27]

Places around Pristina

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

| Name | Description | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn monument | The NEWBORN monument unveiled on the day of the declaration of independence on 17 February 2008. |

|

| Mother Teresa Boulevard | The Mother Teresa Boulevard. | |

| The Museum of Kosovo | The Kosovo Museum has an extensive collection of archaeological and ethnological artifacts, including the Neolithic Goddess on the Throne terracotta, unearthed near Pristina in 1960.[28] |

|

| City Stadium | Home to football club, KF Prishtina |

|

| National Theatre | The national theatre of the Republic of Kosovo |

|

| Skanderbeg Monument | A monument dedicated to Skanderbeg. |

|

| Supreme Court | The supreme court of the Republic of Kosovo |

|

| The Stone Mosque | One of the oldest mosques in Prishtina |

|

Culture

The Museum of Kosovo is located in an Austro-Hungarian inspired building originally built for the regional administration of the Ottoman Vilayet of Kosovo. From 1945 until 1975 it served as headquarters for the Yugoslav National Army. In 1963 it was sold to the Kosovo Museum. From 1999 until 2002, the European Agency for Reconstruction had its main office in the museum building.

The Kosovo Museum has an extensive collection of archaeological and ethnological artifacts, including the Neolithic Goddess on the Throne terracotta, unearthed near Pristina in 1960[28] and depicted in the city's emblem. Although a large number of artifacts from antiquity is still in Belgrade, even though the museum was looted in 1999.

The Clock Tower (Sahat Kulla) dates back to the 19th century. Following a fire, the tower has been reconstructed using bricks. The original bell was brought to Kosovo from Moldavia. It bore an inscription reading "this bell was made in 1764 for Jon Moldova Rumen." In 2001, the original bell was stolen. The same year, French KFOR troops replaced the old clock mechanism with an electric one. Given Kosovo's electricity problems the tower is struggling to keep time.

Environment

City Park was a badly managed, and was the only real green place in Pristina.[citation needed] Three markets (one of them very large) used to be a hotspot for dumping waste and other materials on the roads.[citation needed]

After the war of 1999, Pristina has changed dramatically.[citation needed] City Park has been fully changed.[citation needed] It now has stone pathways, tall trees, flowers have been planted and a public area has been built for children.[citation needed] The much larger Gërmia Park, located to the east of the city is the best place for a family to go and relax. Restaurants, small paths for people to have a run and a large outdoor swimming pool, basketball and volleyball court have been built for the pleasure of the citizens. Lately a new green place called Tauk Bashqe has been made half way between Gërmia and City Park.[citation needed]

After the construction of the new Mother Teresa Square, many trees and flowers have been planted. This had a big impact on the city because of the trees releasing oxygen in the air. Many old buildings in front of the government building have been cleared to provide open space.[citation needed]

Education

Universities

Sport

Basketball has been, since 2000, one of the most popular sports in Pristina. In this sport Pristina is represented in the Basketball National League by two teams. Streetball Kosova is a traditionally organized sport and cultural event in Germia Lake in Pristina, since Year 2000, too. Football is also very popular. Pristina's representatives KF Prishtina play their home games in the city's stadium.

Handball is also very popular. Pristina's representatives are recognised internationally and play international matches.

Demographics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

Ottoman Empire

The Ottomans started conducting census surveys in Rumelia in 1486. Approximate populations reported were:

- 1486: 392 families

- 1487: 412 Christian households and 94 Muslim households

- 1569: 692 families

- 1669: 2,060 families

- 1685: 3,000 families

- 1689: 4,000 families

From 1850, surveys were conducted in the Vilayet of Kosovo. Populations reported were:

- 1850: 12,000 citizens, in 3,000 families

- 1902: 18,000 citizens, in 3,760 families

Serbia and Kingdom of Yugoslavia

- The 1921 official population census conducted by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes listed 14,338 citizens.

- The 1931 official population census organised by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia listed 18,358 inhabitants by mother languages:

- Turkish – 7,573 (41%)

- Serbian – 5,738 (31%)

- Albanian – 2,351 (13%)

- other languages (Romani, Circassian etc.) – 2,651 (14%)

Socialist Yugoslavia

The 1948 official population census of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija organised by the government of the People's Republic of Serbia under the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia government recorded 19,631 citizens in 4,667 families.

The 1953 official population census of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija organised by the government of Serbia under the Yugoslav government recorded 24,229 citizens:

- 9,034 Albanians (37%)

- 7,951 Serbs and Montenegrins (33%)

- 4,726 Turks (20%)

- 2,518 Roma and others (10%)

The 1971 official population census of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo organised by the government of the Socialist Republic of Serbia under the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia government 69,514 citizens in 14,813 families:

- 96,00 Serbs and Montenegrins (28%)

- 4,00 Roma (6%)

The 1981 official population census of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo organised by the government of the Socialist Republic of Serbia under the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia government 108,083 citizens in 21,017 families:

- 75,803 Albanians (70%)

- 21,067 Serbs and Montenegrins (19%)

- 5,101 Roma (5%)

- 2,504 Muslims (2%)

According to the last census in 1991 (boycotted by the Albanian majority), the population of the Pristina municipality was 199,654, including 77.63% Albanians, 15.43% Serbs and Montenegrins, 1.72% Muslims by nationality, and others.[29] This census cannot be considered accurate as it is based on previous records and estimates.

In 2004 it was estimated that the population exceeded half a million, and that Albanians form around 98% of it. The Serbian population in the city has fallen significantly since 1999, many of the city's Serbs having fled or been expelled following the end of the war. In early 1999 Pristina had about 230,000 inhabitants. There were more than 40,000 Serbs and about 6,500 Romas with the remainder being Albanians.

| Ethnic Composition, Including IDPs1 | |||||||||

| Year | Albanians | % | Serbs | % | Roma | % | Others2 | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 census3 | 161,314 | 78.7 | 27,293 | 13.3 | 6,625 | 3.2 | 9,861 | 4.8 | 205,093 |

| 19984 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 225,388 |

| February 2000 estimate5 | 550,000 | 97.4 | 12,000 | 2.2 | 1,000 | 0.1 | 1,800 | 0.3 | 564,800 |

| Source: Template:PDFlink, June 2006, page 2 (Table 1.1). 1. IDP: Internally displaced person. | |||||||||

Notable people

- Xhavit Bajrami, kickboxer

- Rita Ora, singer-songwriter and actress

- Labinot Haliti, football player

- Anđelko Karaferić, Serbian musician, Professor of Counterpoint and Associate Dean at the University of Pristina Faculty of Arts.

- Jasmina Novokmet, Serbian conductor, Professor of Conducting and former Associate Dean at the University of Pristina Faculty of Arts.

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

|

Pristina is twinned with: |

See also

Notes and references

Notes:

References:

- ^ "Define Pristina". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Define Prishtina". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Official gov't census: http://esk.rks-gov.net/rekos2011/repository/docs/REKOS%20LEAFLET%20ALB%20FINAL.pdf

- ^ SNOJ, Marko. 2007. Origjina e emrit të vendit Prishtinë. In: BOKSHI, Besim (ed.). Studime filologjike shqiptare: konferencë shkencore, 21–22 nëntor 2007. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës, 2008, pp. 277–281.

- ^ This etymology is mentioned in ROOM, Adrian: Placenames of the World, Second Edition, McFarland, 2006, page 304. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3

- ^ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1961–1990" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Warrander, Gail (2007). Kosovo: The Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, 23 high street, chalfont st peter, bucks SL9 9QE, England: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. pp. 85–88. ISBN 1-84162-199-4. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Chapman 2000, p. 239

- ^ "Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι, Δαρδανίωνες" Dardanioi, Georg Autenrieth, "A Homeric Dictionary", at Perseus]

- ^ Latin Dictionary

- ^ [1], The Cambridge ancient history: The fourth century B.C. Volume 6 of The Cambridge ancient history, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, ISBN 0-521-85073-8, ISBN 978-0-521-85073-5, Authors: D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Editors: D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Edition 2, Publisher: Cambridge University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-521-23348-8, ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4.

- ^ Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). James P. Mallory (ed.). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel Guy (2006). Encyclopedia Of Ancient Greece. Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-97334-2.

- ^ Hauptstädte in Südosteuropa: Geschichte, Funktion, nationale Symbolkraft by Harald Heppner, page 134

- ^ a b Archaeological Guide of Kosovo Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport, Archaeological Institute of Kosovo, Pristina 2012

- ^ Bogdanović, Dimitrije (2000) [1984]. "Albanski pokreti 1908–1912.". In Antonije Isaković (ed.). Knjiga o Kosovu (in Serbian). Vol. 2. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

... ustanici su uspeli da ... ovladaju celim kosovskim vilajetom do polovine avgusta 1912, što znači da su tada imali u svojim rukama Prištinu, Novi Pazar, Sjenicu pa čak i Skoplje ... U srednjoj i južnoj Albaniji ustanici su držali Permet, Leskoviku, Konicu, Elbasan, a u Makedoniji Debar ...

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_chapter=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and the Conduct of the Balkan Wars". Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Piece. 1914. p. 47. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

This demonstration of Turkish weakness encouraged new allies, the more so that the promises of Albanian autonomy, covering the four vilayets of Macedonia and Old Servia, directly threatened the Christian nationalities with extermination.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. estover road plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. xxxiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-7231-8. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Murray 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet The three Yugoslavias: state-building and legitimation, 1918–2005

- ^ "Kosovo Albanians 'driven into history'". BBC. April 1, 1999. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "Indictment against Milosevic and others". Americanradioworks.publicradio.org. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "EuroNews Serbs in Kosovo vote in Gracanica and Mitrovica published February 3, 2008 accessed February 3, 2008". Euronews.net. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ Komuna e Prishtinës: Investime të mëdha në infrastrukturë

- ^ Macedonia participates in large Kosovo investment

- ^ New Kosova Report: Record setting skyscraper to go up in Pristina

- ^ Todays Zaman: Kosovo to open to world with Turkish-built airport, by Ali Aslan Kiliç, 14 August 2010, Saturday

- ^ a b Thorpe, Nick (2007-06-04). "Kosovo contest for state symbols". BBC. Pristina. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ Statistic data for the municipality of Priština – grad[dead link]

- ^ "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi - Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ^ "Turkey's Bursa, Kosovo's Pristina become sister cities" worldbulletin.net 2 September 2010 Link accessed 2 September 2010

- ^ "Kardeş Şehirler". Bursa Büyükşehir Belediyesi Basın Koordinasyon Merkez. Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ "Twinning Cities: International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ Twinning Cities: International Relations. Municipality of Tirana. www.tirana.gov.al. Retrieved on 2008-01-25.

External links

- Pristina In Your Pocket city guide

Pristina travel guide from Wikivoyage

Pristina travel guide from Wikivoyage- University of Pristina

- Pristina Airport

- Pristina Bus Timetables and Maps