Second Cold War: Difference between revisions

→top: too much detail goes to Background for now |

→Ideology and propaganda: Removed a chunk of synth and OR that was not found in sources. Other parts were removed for not pertaining to the subject. |

||

| Line 215: | Line 215: | ||

==Ideology and propaganda== |

==Ideology and propaganda== |

||

{{also|Putinism}} |

{{also|Putinism}} |

||

Putin and Russia as a whole lost respect for the values and moral authority of the West, creating a "values gap" between Russia and the West.<ref name=Trenin>[http://carnegieendowment.org/2007/03/01/russia-redefines-itself-and-its-relations-with-west/3lz "Russia Redefines Itself and Its Relations with the West"], by [[Dmitri Trenin]], ''[[The Washington Quarterly]]'', Spring 2007</ref> Putin has promoted his brand of conservative Russian values, and has emphasized the importance of religion.<ref name=NBuckley>{{cite news|last1=Buckley|first1=Neil|title=Putin urges Russians to return to values of religion|url=http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/cdedfd64-214f-11e3-a92a-00144feab7de.html#axzz3MhjQRmIS|accessdate=23 December 2014|publisher=Financial Times|date=19 September 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Russia funds [[international broadcasting|international broadcasters]] such as [[RT (TV network)|RT]] (formerly known as Russia Today), [[Rossiya Segodnya]] (including [[Sputnik (news agency)|Sputnik]]), [[Russian News Agency "TASS"|TASS]] (formerly known as ITAR-TASS), and other networks and newspapers.<ref name=CMatlack>{{cite news|last1=Matlack|first1=Carol|title=Does Russia's Global Media Empire Distort the News? You Be the Judge|url=http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-06-04/does-russias-global-media-empire-distort-the-news-you-be-the-judge|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=Bloomberg|date=4 June 2014}}</ref> The Russian government also funds several domestic media networks, and the majority of Russians get their news from state-owned television networks.<ref name=O-M>{{cite news|last1=Spiegel Staff|title=The Opinion-Makers: How Russia Is Winning the Propaganda War|url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/russia-uses-state-television-to-sway-opinion-at-home-and-abroad-a-971971.html|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=Der Spiegel|date=30 May 2014}}</ref><ref name=GTF>{{cite news|last1=Tetrault-Farber|first1=Gabrielle|title=Poll Finds 94% of Russians Depend on State TV for Ukraine Coverage|url=http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/poll-finds-94-of-russians-depend-on-state-tv-for-ukraine-coverage/499988.html|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=The Moscow Times|date=12 May 2014}}</ref> Russia has been accused of funding [[web brigades]] that make pro-Russian comments on social networks and the comments sections of media websites.<ref name=DSindelar>{{cite news|last1=Sindelar|first1=Daisy|title=The Kremlin's Troll Army|url=http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-kremlins-troll-army/375932/|accessdate=21 January 2015|publisher=The Atlantic|date=12 August 2014}}</ref><ref name=PGreg>{{cite news|last1=Gregory|first1=Paul Roderick|title=Putin's New Weapon In The Ukraine Propaganda War: Internet Trolls|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/paulroderickgregory/2014/12/09/putins-new-weapon-in-the-ukraine-propaganda-war-internet-trolls/|accessdate=21 January 2015|publisher=Forbes|date=9 December 2014}}</ref> Both Russia and NATO were said in 2014 to be engaged in a [[propaganda]] war.<ref name=MDejevsky>{{cite news|last1=Dejevsky|first1=Mary|title=News of a Russian arms buildup next to Ukraine is part of the propaganda war|url=http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/11/russian-arms-buildup-ukraine-propaganda-war-nato|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=The Guardian|date=11 April 2014}}</ref> |

Russia funds [[international broadcasting|international broadcasters]] such as [[RT (TV network)|RT]] (formerly known as Russia Today), [[Rossiya Segodnya]] (including [[Sputnik (news agency)|Sputnik]]), [[Russian News Agency "TASS"|TASS]] (formerly known as ITAR-TASS), and other networks and newspapers.<ref name=CMatlack>{{cite news|last1=Matlack|first1=Carol|title=Does Russia's Global Media Empire Distort the News? You Be the Judge|url=http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-06-04/does-russias-global-media-empire-distort-the-news-you-be-the-judge|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=Bloomberg|date=4 June 2014}}</ref> The Russian government also funds several domestic media networks, and the majority of Russians get their news from state-owned television networks.<ref name=O-M>{{cite news|last1=Spiegel Staff|title=The Opinion-Makers: How Russia Is Winning the Propaganda War|url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/russia-uses-state-television-to-sway-opinion-at-home-and-abroad-a-971971.html|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=Der Spiegel|date=30 May 2014}}</ref><ref name=GTF>{{cite news|last1=Tetrault-Farber|first1=Gabrielle|title=Poll Finds 94% of Russians Depend on State TV for Ukraine Coverage|url=http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/poll-finds-94-of-russians-depend-on-state-tv-for-ukraine-coverage/499988.html|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=The Moscow Times|date=12 May 2014}}</ref> Russia has been accused of funding [[web brigades]] that make pro-Russian comments on social networks and the comments sections of media websites.<ref name=DSindelar>{{cite news|last1=Sindelar|first1=Daisy|title=The Kremlin's Troll Army|url=http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-kremlins-troll-army/375932/|accessdate=21 January 2015|publisher=The Atlantic|date=12 August 2014}}</ref><ref name=PGreg>{{cite news|last1=Gregory|first1=Paul Roderick|title=Putin's New Weapon In The Ukraine Propaganda War: Internet Trolls|url=http://www.forbes.com/sites/paulroderickgregory/2014/12/09/putins-new-weapon-in-the-ukraine-propaganda-war-internet-trolls/|accessdate=21 January 2015|publisher=Forbes|date=9 December 2014}}</ref> Both Russia and NATO were said in 2014 to be engaged in a [[propaganda]] war.<ref name=MDejevsky>{{cite news|last1=Dejevsky|first1=Mary|title=News of a Russian arms buildup next to Ukraine is part of the propaganda war|url=http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/11/russian-arms-buildup-ukraine-propaganda-war-nato|accessdate=25 December 2014|publisher=The Guardian|date=11 April 2014}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:47, 24 November 2015

It has been suggested that portions of this article be split out into articles titled Foreign policy of Vladimir Putin and NATO–Russia relations. (Discuss) (November 2015) |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Cold War II,[1][2] also known as the New Cold War,[3] and Cold War 2.0,[4] refers to conflicts that allegedly pitch Russia against the Western World akin to the Cold War pitching the Soviet Empire against the West. Some sources use the term as a possible[5] (or very unlikely[6]) future event, while others have used the term to describe ongoing renewed tensions, hostilities, and political rivalry that intensified dramatically in 2014 between the Russian Federation on the one hand, and the United States, European Union, and some other countries on the other hand.[7]

Tensions escalated in 2014 after Russia's annexation of Crimea, and military intervention in Ukraine. In October 2015, some observers judged the developments in Syria to be a proxy war between Russia and the U.S.,[8][9] and even a "a proto-world war".[10]

The original Cold War was a geopolitical struggle between the Western world, with the United States in the foreground, and the Soviet Union (USSR) and its communist satellite states, that went on from the mid-1940s to 1991; and the term "Cold War II" implies a continuation of the struggle between NATO and Russia. While some notable figures such as Mikhail Gorbachev warned in 2014, against the backdrop of Russia–West political confrontation over the Ukrainian crisis,[11] that the world was on the brink of a New Cold War, or that a New Cold War was already occurring,[12] others argued that the term did not accurately describe the nature of relations between Russia and the West.[13] While the new tensions between Russia and the West have similarities with those during the original Cold War, there are also major dissimilarities such as modern Russia's increased economic ties with the outside world, which may potentially constrain Russia's actions[14] and provides it with new avenues for exerting influence.[15] The term Cold War II has therefore been described as a misnomer.[16]

Background

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (November 2015) |

1989[17] |

Area (Mm²) | |

|---|---|---|

| Russian SFSR | 147,400,537 | 17,075 |

| Ukrainian SSR | 51,706,742 | 604 |

| Uzbek SSR | 19,905,158 | 447 |

| Kazakh SSR | 16,536,511 | 2,717 |

| Byelorussian SSR | 10,199,709 | 208 |

| Azerbaijan SSR | 7,037,867 | 87 |

| Georgian SSR | 5,443,359 | 70 |

| Tajik SSR | 5,108,576 | 143 |

| Moldavian SSR | 4,337,592 | 34 |

| Kirghiz SSR | 4,290,442 | 199 |

| Lithuanian SSR | 3,689,779 | 65 |

| Turkmen SSR | 3,533,925 | 488 |

| Armenian SSR | 3,287,677 | 30 |

| Latvian SSR | 2,680,029 | 65 |

| Estonian SSR | 1,572,916 | 45 |

| USSR | 286,730,819 | 22,402 |

The Cold War confrontation between the Eastern Bloc and the Western Bloc took place from the late 1940s to 1991. It arose after the allies of World War II, led by the Marxist–Leninist Soviet Union and the democratic capitalist United States and United Kingdom, defeated the Axis powers. Though the allies had had several wartime conferences regarding cooperation during and after the war, relations between the capitalist and communist powers soured after incidents such as Soviet territorial claims to Turkey, the Greek Civil War, the 1948 pro-Soviet coup d'état in Czechoslovakia and the Berlin Blockade. Military alliances formalized the division between the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc, as NATO united the Western Bloc countries in a military alliance in 1949 and the Eastern Bloc established the similar Warsaw Pact in 1955. Though the Warsaw Pact and NATO never engaged in open warfare, the two sides fought several proxy wars and backed competing political movements throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Throughout the period, relations between the two sides ebbed and flowed between acute crises and rapprochement (détente). The Cold War definitively ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991.[19][20][21]

With the Cold War over, political scientists looked for new paradigms to understand world politics.[22][23] In 1992, Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man, in which he argued that all states would eventually adopt liberal democracy. The next year, Samuel P. Huntington published his essay The Clash of Civilizations, in which he posited that civilizations were destined to compete based on their cultural and religious identities.[23] Huntington placed Russia at the core of the Orthodox civilization, while NATO and a few other countries comprised the West. Huntington's thesis continues to hold influence among many, although other political scientists reject his ideas.[23] In Russia, many struggled to accept the end of the political union of the USSR; the term "near abroad" came to refer to the other post-Soviet states, with the implication that Russia had certain "rights" in the near abroad.[24]

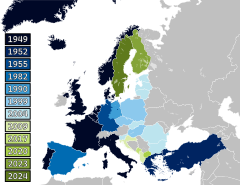

Between 1999 and 2013, eleven countries that had been either Warsaw Pact members or part of the Soviet Union, chose to join both the European Union and NATO. Russia voiced deep concern over this NATO enlargement and was particularly opposed to NATO's expansion to the Baltic states.[25] In addition to seeing the expansion of NATO as a threat, many Russian leaders also saw the expansion of NATO into Russia's former sphere of influence as an insult to Russia's status as a great power.[26] Russia also voiced concern over the United States national missile defense plans, as it saw both the NATO expansion and the US missile defense program as a potential threat to Russian national security.[25] In 2012, the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia and First Deputy Minister of Defence, Nikolay Makarov, said that if the United States were to deploy an anti-ballistic missile shield in Poland and Czech Republic, Russia would respond by deploying Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad.[27] After a four-year stint as Prime Minister of Russia, in 2012 Putin returned to the Russian presidency and continued with new vigour to advance a brand of ideology known as Putinism, which promotes conservative Russian values and opposition to the West, particularly the United States.[28] Nevertheless, in 2013, 51% of Russians had a favorable view of the U.S., albeit down from 57% in 2010.[29]

In December 2012, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said the U.S. would seek to counter Russian proposals for creating a Eurasian Economic Union of former Soviet states: "It's not going to be called that [Soviet Union]. It's going to be called customs union, it will be called the Eurasian Union and all of that, but let's make no mistake about it. We know what the goal is and we are trying to figure out effective ways to slow down or prevent it".[30] On September 12, 2013, in the context on Barack Obama's comment about American exceptionalism during his September 10, 2013, talk to the American people while considering military action on Syria, Putin criticized Obama saying that "It is extremely dangerous to encourage people to see themselves as exceptional, whatever the motivation."[31]

In October 2014, Putin delivered his Valdai club speech, which sharply criticized the Western powers' foreign policy and actions, especially those of the United States — who, in his opinion, "having declared itself the winner of the Cold War", had taken steps that threw the system of global and regional security as established after World War II "into sharp and deep imbalance":

The Cold War ended, but it did not end with the signing of a peace treaty [...]. This created the impression that the so-called ‘victors’ in the Cold War had decided to pressure events and reshape the world to suit their own needs and interests. If the existing system of international relations, international law and the checks and balances in place got in the way of these aims, this system was declared worthless, outdated and in need of immediate demolition."[32]

Russia and NATO: End of cooperation and military build-up

Relations between NATO and Russia, established in the early 1990s,[clarification needed] began to appreciably deteriorate prior to 2014,[25] due to Russia's displeasure with the NATO expansion and Putin's Russia being increasingly assertive in what it refers to as its near abroad.

2014

On 1 April 2014, in response to the Ukraine crisis, NATO decided to "suspend all practical civilian and military cooperation between NATO and Russia".[33]

In spring 2014, the Russian Defense Ministry announced it was planning to deploy additional forces in Crimea, which had just been annexed by Russia, as part of beefing up its Black Sea Fleet,[34][better source needed] including re-deployment by 2016 of nuclear-capable Tupolev Tu-22M3 ('Backfire') long-range strike bombers — which used to be the backbone of Soviet naval strike units during the Cold War, but were later withdrawn from bases in Crimea.[35] The move alarmed NATO: in November 2014, NATO's top military commander US General Philip Breedlove said that the alliance was "watching for indications" amid fears over the possibility that Russia could move any of its nuclear arsenal to the peninsula.[36] In December 2014, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said this would be a legitimate action as "Crimea has now become part of a country that has such weapons under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons."[37]

At the NATO Wales summit in early September 2014, the NATO-Ukraine Commission adopted a Joint Statement that "strongly condemned Russia’s illegal and illegitimate self-declared "annexation" of Crimea and its continued and deliberate destabilization of eastern Ukraine in violation of international law";[38] this position was re-affirmed in the early December statement by the same body.[39]

A report released in November 2014 highlighted the fact that close military encounters between Russia and the West (mainly NATO countries) had jumped to Cold War levels, with 40 dangerous or sensitive incidents recorded in the eight months alone, including a near-collision between a Russian reconnaissance plane and a passenger plane taking off from Denmark in March 2014 with 132 passengers on board.[40] The 2014 unprecedented increase[41] in Russian air force and naval activity in the Baltic region prompted NATO to step up its longstanding rotation of military jets in Lithuania.[42] Similar Russian air force activity in the Asia-Pacific region, relying on the resumed use of the previously abandoned Soviet military base at Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, in 2014, was officially acknowledged by Russia in January 2015.[43] In March 2015, Russia's defense minister Sergey Shoygu said that Russia's long-range bombers would continue patrolling various parts of the world and expand into other regions.[44]

In July 2014, the U.S. formally accused Russia of having violated the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty by testing a prohibited medium-range ground-launched cruise missile (presumably R-500,[45] a modification of Iskander)[46] and threatened to retaliate accordingly.[46][47] In early June 2015, the U.S. State Department reported that Russia had failed to correct the violation of the I.N.F. Treaty; the U.S. government was said to have made no discernible headway in making Russia so much as acknowledge the compliance problem.[48] The US government's October 2014 report claimed that Russia had 1,643 nuclear warheads ready to launch (an increase from 1,537 in 2011) – one more than the US, thus overtaking the US for the first time since 2000; both countries' deployed capacity being in violation of the 2010 New START treaty that sets a cap of 1,550 nuclear warheads.[49][50] Likewise, even before 2014, the US had set about implementing a large-scale program, worth up to a trillion dollars, aimed at overall revitalization of its atomic energy industry, which includes plans for a new generation of weapon carriers and construction of such sites as the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico and the National Security Campus in south Kansas City.[51][52]

At the end of 2014, Putin approved a revised national military doctrine, which listed NATO’s military buildup near the Russian borders as the top military threat.[53][54]

2015

In early February 2015, NATO diplomats said that concern was growing in NATO over Russia's nuclear strategy and indications that Russia's nuclear strategy appeared to point to a lowering of the threshold for using nuclear weapons in any conflict.[55] The conclusion was followed by British Defense Secretary Michael Fallon saying that Britain must update its nuclear arsenal in response to Russian modernization of its nuclear forces.[56] Later in February, Fallon said that Putin could repeat tactics used in Ukraine in Baltic members of the Nato alliance; he also said: "Nato has to be ready for any kind of aggression from Russia, whatever form it takes. Nato is getting ready."[57] Fallon noted that it was not a new cold war with Russia, as the situation was already “pretty warm”.[57]

In March 2015, Russia, citing NATO's de facto breach of the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, said that the suspension of its participation in it, announced in 2007, was now "complete" through halting its participation in the consulting group on the Treaty.[58][59]

Early April 2015 saw the publication of the leaked information ascribed to semi-official sources within the Russian military and intelligence establishment, about Russia's alleged preparedness for a nuclear response to certain inimical non-nuclear acts on the part of NATO; such implied threats were interpreted as "an attempt to create strategic uncertainty" and undermine Western political cohesion.[60] Also in this vein, Norway’s defense minister, Ine Eriksen Soreide, noted that Russia had "created uncertainty about its intentions".[61]

In June 2015, an independent Russian military analyst was quoted by a major American newspaper as saying: “Everybody should understand that we are living in a totally different world than two years ago. In that world, which we lost, it was possible to organize your security with treaties, with mutual-trust measures. Now we have come to an absolutely different situation, where the general way to ensure your security is military deterrence.”[62]

In late June 2015, while on a trip to Estonia, US Defence Secretary Ashton Carter said the U.S. would deploy heavy weapons, including tanks, armoured vehicles and artillery, in Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania.[63] The move was interpreted by Western commentators as marking the beginning of a reorientation of NATO′s strategy.[64] It was called by a senior Russian Defence Ministry official ″the most aggressive act by Washington since the Cold War″[65] and criticised by the Russian Foreign Ministry as "inadequate in military terms" and "an obvious return by the United States and its allies to the schemes of ‘the Cold War’".[66][67] On its part, the U.S. expressed concern over Putin's announcement of plans to add over 40 new ballistic missiles to Russia′s nuclear weapons arsenal in 2015.[65] American observers and analysts, such as Steven Pifer, noting that the U.S. had no reason for alarm about the new missiles, provided that Russia remained within the limits of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), viewed the ratcheting-up of nuclear saber-rattling by Russia′s leadership as mainly bluff and bluster designed to conceal Russia′s weaknesses;[68] however, Pifer suggested that the most alarming motivation behind this rhetoric could be Putin seeing nuclear weapons not merely as tools of deterrence, but as tools of coercion.[69] Meanwhile, at the end of June 2015, it was reported that the production schedule for a new Russian MIRV-equipped, super-heavy thermonuclear intercontinental ballistic missile Sarmat, intended to replace the obsolete Soviet-era SS-18 Satan missiles, was slipping.[70] Also noted by commentators were the inevitable financial and technological constraints that would hamper any real arms race with the West, if such course were to be embarked on by Russia.[62]

The Spearhead Force

On 2 December 2014, NATO foreign ministers announced an interim Spearhead Force (the 'Very High Readiness Joint Task Force') created pursuant to the Readiness Action Plan agreed on at the NATO Wales summit in early September 2014 and meant to enhance NATO presence in the eastern part of the alliance.[71][72] In June 2015, in the course of military drills held in Poland, NATO tested the new rapid reaction force for the first time, with more than 2,000 troops from nine states taking part in the exercise.[73][74] Upon the end of the drills, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced that the Spearhead Force deployed in Eastern Europe would be increased to 40,000 troops.[75]

Russia–West confrontation over Ukraine

Overview of Russia–Ukraine relations

Kiev, the capital of modern Ukraine, had been the capital of the medieval Rus' state as well as the seat of the primates of the Russian Church. Most of the territory that currently belongs to Ukraine was within the Russian Empire by the end of the 18th century, after the partitions of Poland and the Treaty of Jassy (1792). The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, constituted in 1922, and Ukraine's 1991 declaration of independence contributed to ensuring the peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of that year.

In the aftermath of the Soviet Union's demise, Ukraine and the Russian Federation experienced tensions regarding the status of Crimea, which had been transferred by the central government of the USSR from Russia to Ukraine in 1954, and issues related to the status of the Black Sea Fleet. However, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum defused the dispute, as Ukraine gave up its nuclear stockpile in return for assurances from Russia, the USA, and the UK that Ukraine's security and integrity would be upheld. The bickering between the two countries over the ex-Soviet Black Sea Fleet was settled by the 1997 Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet. Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma (1994–2005), who strove to maintain peaceful relations with Russia,[76] did not seek re-election in the 2004 national ballot, which featured Putin's favorite Viktor Yanukovych and Viktor Yushchenko, supported by most Western governments. After two rounds of voting, on 23 November 2004, the Central Election Commission declared Yanukovych the winner, but accusations of fraud led to a series of protests known as the Orange Revolution. The Orange Revolution increased tensions between Putin and Western countries, as Putin saw the Orange Revolution as a product of Western machinations and a foreshadowing of an assault on his regime.[28] Finally, the Supreme Court of Ukraine ordered a re-run of the second ballot and the new election was won by Yuschenko. Yuschenko pursued the policy of European integration and aspired to NATO membership, but NATO chose not to offer membership to Ukraine, as many Western leaders sought to avoid inflaming tensions with Russia.[77] Yanukovych won the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, and announced a new policy of non-alignment.[77] Ukraine continued to maintain ties with both Russia and the European Union; in 2013, about a third of Ukraine's foreign trade was with the EU and roughly the same proportion was its trade with Russia.[78] The Yanukovych government negotiated the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement. However, Yanukovych, under pressure from Russian President Vladimir Putin, refused to sign the agreement.[79] Yanukovych's decision sparked a series of protests known as the Euromaidan.

2014–15 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine

The Euromaidan protests led to the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, which had major implications for Ukraine in both domestic politics and foreign relations. After several violent clashes, in February 2014, Yanukovych was impeached and removed from office by a vote of the Ukrainian parliament.[80] Following Yanukovych's removal, an interim government took power, and May 2014 presidential election saw pro-Western businessman Petro Poroshenko elected President of Ukraine. In June 2014, Poroshenko signed the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement, which his predecessor, Yanukovych, had rejected in 2013. The Euromaidan and Yanukovych's removal from power led to pro-Russian unrest in Eastern and Southern Ukraine starting in February 2014. Following this unrest, Russia conducted a stealth invasion of parts of Ukraine, sparking an international crisis. In March 2014, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea held the referendum, thereby declaring its secession from Ukraine, and shortly thereafter signed a treaty to join the Russian Federation. The annexation was not recognized by the overwhelming majority of the world community and provoked the imposition on 17 March 2014 of the first round of sanctions against Russia by Canada, the United States, and the European Union.

The term "Cold War II" gained currency and relevance as tensions between Russia and the West escalated throughout the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine followed by the Russian military intervention and especially the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 in July 2014. By August 2014, both sides had implemented economic, financial, and diplomatic sanctions upon each other: virtually all Western countries, led by the US and EU, imposed restrictive measures on Russia; the latter reciprocally introduced retaliatory measures. Besides, Russia was barred from a slimmed-down June 2014 G7 summit in Brussels that had been planned as a G8 summit to be held in Russia.[81][82] Also, the Australian government explored the option of disinviting Putin to the November 2014 G20 summit in Brisbane, to which Putin was eventually invited and did go but was reported to be frozen out or outright rebuked by some other leaders.[83][84] On the eve of the summit, the host, Tony Abbott, accused Putin of "bullying" Ukraine and trying to "recreate the lost glories of Tsarism and the Soviet Union";[85][86] meanwhile, Putin was reported to have "ordered a Russian military flotilla of four ships to sail to the Queensland coast, adding to the surreal Cold War atmosphere".[86]

In August 2014, the ITAR-TASS news agency cited the senior Russian law-maker Aleksey Pushkov as saying that Russia’s relations with the United States had become worse than in the 1970s and had no prospects for improvement.[87] Ukrainian President Poroshenko raised the possibility of holding a referendum on joining NATO.[88]

In December 2014, Ukraine renounced its policy of non-alignment, provoking harsh reactions from Russian leaders, who strongly oppose Ukraine's potential membership in NATO.[89]

Tensions in other ex-Soviet countries

Besides Ukraine, several other ex-Soviet and ex-communist countries continue to be flashpoints in the tug-of-war between the West and Russia.[88] Frozen conflicts in Georgia and Moldova have been major areas of dispute,[88][90] as both countries have breakaway regions that favor annexation by Russia.[91] The Baltic Sea and other areas have also caused tension between Russia and the West.[88][92] The Crimean crisis sparked new worries that Russia might try to further remake the borders of Eastern Europe.[93]

Georgia and the Caucasus

Since the mid-2000s, Georgia has sought closer relations with the West, while Russia has strongly opposed the expansion of Western institutions to its southern border. Georgia has a long connection with the Russian Federation, as it was a republic of the Soviet Union, and became part of the Russian Empire in 1801. In 2003, the Rose Revolution forced Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze to resign from office. Shevardnadze had been the leader of the Georgian Communist Party when Georgia was one of the republics of the Soviet Union, and Shevardnadze led Georgia for most of its first decade of independence.[94] Shevardnadze's successor, Mikheil Saakashvili, pursued closer relations with the West.[95] Under President George W. Bush, the United States sought to invite Ukraine and Georgia into NATO. However, Georgia's potential membership in NATO ran into opposition from other NATO members and Russia.[25][96] Partly in response to the potential expansion of NATO, Russia initiated the 2008 Russo-Georgian diplomatic crisis by lifting CIS sanctions on Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Though considered to be part of Georgia by the United Nations, Abkhazia and South Ossetia have both sought to secede from Georgia since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and both are strongly supported by Russia.[97] The Russo-Georgian War broke out in August 2008, as Georgia and Russia competed for influence in South Ossetia. Russia was strongly criticized by many Western countries for its part in the war, and the war heightened tensions between NATO and Russia.[25] The war ended with a unilateral Russian withdrawal of forces from parts of Georgia, but Russian forces continue to occupy parts of Georgia. In November 2014, a Russian-Abkhazian treaty was met with condemnation from Georgia and many Western countries, who feared that Russia might annex Abkhazia much like it annexed Crimea.[98] Georgia continues to pursue a policy of integration with the West.[99] Georgia holds a strategic position for the European Union, as it gives the EU access to oil in Azerbaijan and Central Asia without having to rely on Russian pipelines.[100]

Besides Georgia, the other two Caucasus states, Armenia and Azerbaijan, have also been a part of the rivalry between Russia and the West. The two countries are long-time rivals, and have a long-running dispute regarding control of Nagorno-Karabakh.[101] Armenia has close ties with Russia, while Azerbaijan has close ties to the United States and Turkey, both of which are members of NATO.[101] However, NATO also ties to Armenia, and both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been speculated as potential future members of NATO.[102] Armenia negotiated an Association Agreement with the European Union but, similar to Ukraine, Armenia chose to reject the deal in 2013.[103] The next year, Armenia voted to join the Eurasian Economic Union,[104] the Russian-backed free trade zone that seeks to rival the European Union.[105] However, Armenian leaders have also worked towards a free trade agreement with the EU.[104]

Moldova

Much like Ukraine, Moldova has experienced internal debates between those favoring closer ties to the West (including joining the European Union) and those favoring closer ties to Russia (including joining the Russian-backed Eurasian Union).[88] Also like Ukraine, Moldova was a part of the Soviet Union; though Moldova was a part of Romania prior to World War II, it was annexed into the Soviet Union in 1940. In May 2014, Moldova signed a major trade deal with the European Union,[100] causing Russia to apply pressure on the Moldovan economy, which relies heavily on remittances from Russia.[106] The 2014 Moldovan parliamentary elections saw a victory for an alliance of pro-Western integration parties.[88] Moldova is also home to a breakaway region, known as Transnistria, which forms the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations along with Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh.[88] In 2014, Transnistria held a referendum in which it voted to join the Eurasian Economic Union,[88] and Russia has strong influence over the region.[97] A build-up of Russian forces on the Ukrainian-Russian border caused NATO commander Philip Breedlove to speculate that the Russian Federation might attempt to attack Moldova and occupy Transnistria.[107]

Baltic states and Scandinavia

The Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia — all three of which are members of NATO — have warily watched Russian military movements and actions.[88][92] All three countries, within the Russian Empire prior to 1918, had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and Russian leaders were particularly distressed by their accession to NATO and the EU in 2004.[109] In 2014, the Baltic states reported several incursions into their air space by Russian military aircraft.[88] Tensions rose as Russian intelligence forces crossed the Estonian border and captured Estonian intelligence officer Eston Kohver.[92] In October 2014, Sweden engaged in a hunt for a foreign submarine that had entered its waters; suspicions that the submarine was Russian have caused further alarm in the Baltic states.[110] The tensions in the Baltic and other areas have led neighboring Sweden and Finland, both of which have long been neutral states, to openly discuss joining NATO.[109]

In early April 2015, British press publications, with a reference to semi-official sources within the Russian military and intelligence establishment, suggested that Russia was ready to use any means—including nuclear weapons—to forestall NATO moving more forces into the Baltic states.[111][112]

Other European countries

The Russian leadership under Putin sees the fracturing of the political unity within the EU and especially the political unity between the EU and the US as among its main strategic goals.[113] Russia seeks to gain dominant influence in former Eastern Bloc states that are culturally and historically close to it, corrode and undermine Western institutions and values, manipulate public opinion and policy-making throughout Europe.[113]

In 1999, Russia opposed NATO's bombing of Serbia, seen by Russia as a cultural younger brother,[114] during the Kosovo War.[25] Russia strongly opposed Kosovo's independence from Serbia. As the West supported Kosovo's independence, Russia later used the "Kosovo precedent" as justification for its annexation of Crimea and its support of breakaway states in Georgia and Moldova.[115][116]

In November 2014, the German government publicly voiced its concern about what it saw as efforts by Putin to spread Russia's ‘sphere of influence’ beyond former Soviet states in the Balkans in countries such as Serbia, Macedonia, Albania and Bosnia, which could impede those countries' progress towards membership in the European Union.[115][117]

A series of Europe's far-right and hard Eurosceptic political parties such as Bulgaria's Ataka, the Alternative for Germany, France's National Front, the Freedom Party of Austria, Italy's Northern League, the Independent Greeks and Hungary's Jobbik, have been reported to be courted or even funded by Russia.[118][119] Russia’s ideological approach to this type of activity is opportunistic: it supports both far-left and far-right groups, the aim being to exacerbate divides in Western states and destabilise the EU through fringe political parties gaining more clout.[120] The success of these parties in the May 2014 European elections caused concern that a coherent pro-Russian block was forming in the EU parliament.[121]

In early January 2015, public protests in Hungary broke out against Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's perceived move towards Russia.[122] Previously, his government had negotiated secret loans from the Russians, awarded a major nuclear power contract to Rosatom, and made parliament give a green light to Russia’s gas pipeline project in contravention to blocking orders from Brussels.[123]

In early April 2015, the Polish border guard sources were cited as saying that Poland was preparing to build observation towers along its border with the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad;[124][125] the move was linked by the mass media to prior official vaguely-worded confirmation,[126] in December 2013, of Russia′s putative deployment of its advanced modification of nuclear-capable Iskander theatre ballistic missiles in the exclave′s territory,[127] as well as more recent, March 2015, unofficial reports of the same nature.[128]

The prime minister of Montenegro Milo Đukanović went on record in October 2015 to claim that Russia was sponsoring the anti-government and anti-NATO protests in Podgorica.[129][130]

Tensions and proxy conflicts in other regions

Apart from tensions in Europe, Russia and the West have also competed for influence in other regions, including the Greater Middle East and Central Asia. In opposition to the United States, Russia is a major supporter of Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian Civil War.[131] Russia strongly opposed Western actions in both Libya and Iraq.[132] The West and Russia (as well as China) have competed for influence in the five post-Soviet Central Asian states in what has been called "the New Great Game."[133][134][135] However, both Russia and the West have publicly supported efforts to fight Islamic militants in Central Asia.[136] Russia has also attempted to project its military and economic influence into Latin America, an area with which the US has close economic and political ties.[137][138] Russia and NATO countries have also laid claim to territory in the Arctic.[139] Norway has urged NATO to be prepared for potential tensions in the region.[140] NORAD fighters have been scrambled to respond to Russian aircraft near Canadian airspace in the Arctic.[141]

While widely seen by experts both in Russia and in the West as a bid to end Russia′s political isolation imposed by the West in connection with the situation in Ukraine,[142][143][144][145] Russia′s escalation of its efforts in September 2015 to prop up the Assad regime in Syria in the course of the ongoing civil war, on the one hand, and plentiful supply of arms to the rebels by the U.S. on the other hand, resulted in a situation that was judged by The New York Times in mid-October 2015 as turning into an all-out proxy war between the U.S. and Russia.[8] Yet, others, including U.S. senator John McCain, believed it was a proxy war already.[146][9] Jeremy Shapiro, a senior fellow in the Brookings Institution, believed the unfolding situation in and around Syria was "a very, very familiar proxy war cycle from the bad old days of the Cold War".[147]

Ideology and propaganda

Putin and Russia as a whole lost respect for the values and moral authority of the West, creating a "values gap" between Russia and the West.[148] Putin has promoted his brand of conservative Russian values, and has emphasized the importance of religion.[149]

Russia funds international broadcasters such as RT (formerly known as Russia Today), Rossiya Segodnya (including Sputnik), TASS (formerly known as ITAR-TASS), and other networks and newspapers.[150] The Russian government also funds several domestic media networks, and the majority of Russians get their news from state-owned television networks.[151][152] Russia has been accused of funding web brigades that make pro-Russian comments on social networks and the comments sections of media websites.[153][154] Both Russia and NATO were said in 2014 to be engaged in a propaganda war.[155]

Russian state-controlled media played an important role in shaping attitudes towards the Euromaidan and the 2014–15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine,[156] and Russian media has been particularly critical of the United States.[28][157] Russia's freedom of the press has received low scores in the Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders. In 2014, President Putin signed a bill that limited foreign ownership to no more than 20% of any Russian media firm, further tightening state control over Russian media.[158] The Russian government also blocked a number of internet-based media outlets.[159] Russian mass media officials such as RT editor Margarita Simonyan argued in 2014 that Russian-owned channels sought to provide an "alternative" as a counterbalance to Western media.[160]

In 2014, the British TV producer with a decade-long experience in the Russian television, Peter Pomerantsev, wrote:

The new Russia doesn’t just deal in the petty disinformation, forgeries, lies, leaks, and cyber-sabotage usually associated with information warfare. It reinvents reality, creating mass hallucinations that then translate into political action. [...] The invention of Novorossiya is a sign of Russia’s domestic system of information manipulation going global. [...] The point of this new propaganda is not to persuade anyone, but to keep the viewer hooked and distracted — to disrupt Western narratives rather than provide a counternarrative."[161]

In January 2015, the UK, Denmark, Lithuania and Estonia called on the European Union to jointly confront Russian propaganda by setting up a "permanent platform" to work with NATO in strategic communications and boost local Russian-language media.[162] On 19 January 2015, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini said the EU planned to establish a Russia-language mass media body with a target Russian-speaking audience in Eastern Partnership countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, as well as in the European Union countries.[163]

Legal status

Just as with the Cold War, the legal status of any renewed tension may be examined by reference to the legality of particular operations or hostile acts. From the standpoint of international law, attempts to formalize inchoate conflicts like what may be a second Cold War[dubious – discuss] wholesale into existing categories is made very difficult due to the highly politicized nature of the conflict. Moreover, as in the Cold War, international legal argumentation is easily coopted by hostile sides, leading to the use of international legal argument as forms of 'lawfare.' [164]

Buildup of espionage efforts

Russian espionage activities in the West under Putin had been reported to have reached the height of the Cold War levels years before the Ukraine crisis, according to official sources.[165][166][167] The US and its major allies had been aggressively building up their intelligence-gathering capabilities since the attacks on 11 September 2001, with the US intelligence budget having since doubled by 2013.[168]

Czech Republic's secret service reported that an unusually high number of Russian spies, registered officially as tourists, experts, businessmen or academics, visited the Russian embassy in Prague from 2013 onward.[169]

The investigation report published by Newsweek in December 2014 found that Russian spying activity in Europe had returned to levels not seen since the Cold War; moreover, the investigation claimed that Russia had reintroduced the Soviet intelligence practice of so-called ‘influence operations’, whereby both Westerners and Russians resident outside Russia would be doing Moscow’s bidding.[170]

In January 2015, the former CIA Director James Woolsey said that employing the so called "illegals", non-official spies posing as US citizens while being Russian nationals, remained a favorite tactic of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service to obtain trade and financial secrets in the US, especially about the energy sector.[171]

In April 2015, the allegedly Russian government-sponsored cyber-hacking and espionage aimed against the US government computer systems, was reported to have increased significantly.[172]

Trade and economy

| Country | GDP | GDPPC |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 17.4 | 54,596 |

| Germany | 3.9 | 47,589 |

| United Kingdom | 3.1 | 45,653 |

| France | 2.8 | 44,538 |

| Italy | 2.1 | 35,823 |

| Russia | 1.9 | 12,925 |

| Canada | 1.8 | 50,397 |

| Spain | 1.4 | 30,278 |

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation moved towards a more open economy with less state intervention. Russia became an important part of the global economy.[175] In 1998, Russia joined the G7, a forum of eight large developed countries, and Russia was a founding member of the larger G-20. In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization, an organization of governments committed to reducing tariffs and other trade barriers. The opening of the Russia economy allowed greater economic interaction with the West and other areas, and the political tensions between Russia and the West have often influenced economic activities.

These increased economic ties gave Russia access to new markets and capital, as well as a political clout on the West and other countries. The Russian economy is heavily dependent on the export of natural resources such as oil and natural gas, and Russia has used these resources to its advantage. Meanwhile, the US and other Western countries have worked to lessen the dependency of Europe on Russia and its resources.[176] Starting in the mid-2000s, Russia and Ukraine had several disputes in which Russia threatened to cut off the supply of gas. As a great deal of Russia's gas is exported to Europe through the pipelines crossing Ukraine, those disputes affected several other European countries. While Russia claimed the disputes had arisen from Ukraine's failure to pay its bills, Russia may also have been motivated by a desire to punish the pro-Western government that came to power after the Orange Revolution.[177] Gas exports by Russia came to be viewed as its weapon against Western Europe.[15] Under Putin, special efforts were made to gain control over the European energy sector. Russian influence played a major role in canceling the construction of the Nabucco pipeline, which would have supplied natural gas from Azerbaijan, in favor of South Stream (though South Stream itself was also later canceled).[119] Russia has also sought to create a Eurasian Economic Union consisting of itself and other post-Soviet countries.[178]

While Russia's new role in the global economy presented Russia with several opportunities, it also made the Russian Federation more vulnerable to external economic trends and pressures.[14] Like many other countries, Russia's economy suffered during the Great Recession. Following the Crimean Crisis, several countries (including most of NATO) imposed sanctions on Russia, hurting the Russian economy by cutting off access to capital.[179] At the same time, the global price of oil declined.[180] The combination of Western sanctions and the falling crude price in 2014 and thereafter, which was widely seen in Russia as a US–Saudi plot against it,[181] resulted in the ongoing 2014–15 Russian financial crisis.[180] As a way to get around Western sanctions, Russia and China signed on a US$400 billion deal which would supply natural gas to China over the next 30 years. In 2014 Beijing and Moscow signed a 150 billion yuan central bank liquidity swap line agreement to get around American sanctions.[182]

Russia banned import of food from several countries inflating prices in Russia. [183]

See also

References

- ^ Dmitri Trenin (March 4, 2014). "Welcome to Cold War II". Foreign Policy. Graham Holdings. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ As Cold War II Looms, Washington Courts Nationalist, Rightwing, Catholic, Xenophobic Poland, Huffington Post, 15 October 2015.

- ^ Simon Tisdall (November 19, 2014). "The new cold war: are we going back to the bad old days?". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Eve Conant (September 12, 2014). "Is the Cold War Back?". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Pavel Koshkin (Apr 25, 2014). "What a new Cold War between Russia and the US means for the world".

- ^ Lawrence Solomon (October 9, 2015). "Lawrence Solomon: Cold War II? Nyet".

- ^ "Welcome to Cold War II". Foreign Policy. March 4, 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "U.S. Weaponry Is Turning Syria Into Proxy War With Russia". The New York Times. 12 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ a b "U.S., Russia escalate involvement in Syria". CNN. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Untangling the Overlapping Conflicts in the Syrian War". The New York Times. 18 October 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

{{cite news}}: line feed character in|title=at position 27 (help) - ^ Conant, Eve (12 September 2014). "Is the Cold War Back?". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Kendall, Bridget (12 November 2014). "Rhetoric hardens as fears mount of new Cold War". BBC News. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (29 May 2014). "This Isn't A Cold War. And That's Not Necessarily Good". Time. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ a b Stewart, James (7 March 2014). "Why Russia Can't Afford Another Cold War". New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Putin's 'Last and Best Weapon' Against Europe: Gas". 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- ^ “The Cold War II: Just Another Misnomer?”, Contemporary Macedonian Defence, vol. 14. no. 26, June 2014, pp. 49-60

- ^ Almanaque Mundial 1996, Editorial América/Televisa, Mexico, 1995, pages 548-552 (Demografía/Biometría table).

- ^ "Putin calls Soviet collapse a 'geopolitical catastrophe'". San Diego Union Tribune. 25 April 2005.

- ^ "US and Russia renew Cold War rivalry". America Aljazeera.com/. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Managing the New Cold War". Foreign Affairs.com. August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Shuster/Kiev, Simon (24 July 2014). "In Russia, Crime Without Punishment". Time.com. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Said, Edward (4 October 2001). "The Clash of Ignorance". The Nation. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Schrad, Mark (22 September 2014). "Ukraine and ISIS are not justifications of a 'clash of civilizations'". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Safire, William (22 May 1994). "ON LANGUAGE; The Near Abroad". New York Times. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Peter, Laurence (2 September 2014). "Why Nato-Russia relations soured before Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Ward, Steven (6 March 2014). "How Putin's desire to restore Russia to great power status matters". Washington Post. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (3 May 2012). "Russia threatens Nato with military strikes over missile defence system". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Remnick, David (11 August 2014). "Watching the Eclipse". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Opinion of the United States". Pew Research Center.

- ^ Clinton fears efforts to 're-Sovietize' in Europe - Associated Press, 6 December 2012

- ^ Vladimir Putin's comments on American exceptionalism, Syria cause a fuss. CNN. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Nato suspends Russia co-operation". BBC News. UK. 2014-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ New subs, warships, SAMs, troops to be deployed in Crimea RT, May 06, 2014.

- ^ Russia to deploy Tu-22M3 'Backfire' bombers to CrimeaJane's, 27 March 2014.

- ^ NATO 'very concerned' by Russian military build-up in Crimea

- ^ Crimea became part of Russia, which has nuclear weapons according to NPT – Lavrov

- ^ Joint Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 4 September 2014.

- ^ Joint statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 2 December 2014.

- ^ Ewen MacAskill (2014-11-09). "Close military encounters between Russia and the west 'at cold war levels'". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ "Russia Baltic military actions 'unprecedented' - Poland". BBC. UK. 2014-12-28. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ "Four RAF Typhoon jets head for Lithuania deployment". BBC. UK. 2014-04-28. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ "U.S. asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights". Reuters. 2015-03-11. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- ^ "Russian Strategic Bombers To Continue Patrolling Missions". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- ^ Russian INF Treaty Violations: Assessment and Response

- ^ a b Gordon, Michael R. (2014-07-28). "U.S. Says Russia Tested Cruise Missile, Violating Treaty". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ "US and Russia in danger of returning to era of nuclear rivalry". The Guardian. UK. 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (2015-06-05). "U.S. Says Russia Failed to Correct Violation of Landmark 1987 Arms Control Deal". The New York Times. US. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ^ "Russia's deployed nuclear capacity overtakes US for first time since 2000". RT. Moscow. 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ Matthew Bodner (2014-10-03). "Russia Overtakes U.S. in Nuclear Warhead Deployment". The Moscow Times. Moscow. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies: Monterey, CA. January 2014.

- ^ Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (2014-09-21). "U.S. Ramping Up Major Renewal in Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ Russia’s New Military Doctrine Hypes NATO Threat

- ^ Putin signs new military doctrine naming NATO as Russia’s top military threat National Post, December 26, 2014.

- ^ "Insight - Russia's nuclear strategy raises concerns in NATO". Reuters. 4 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (6 February 2015). "Supplying weapons to Ukraine would escalate conflict: Fallon". Reuters. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Russia a threat to Baltic states after Ukraine conflict, warns Michael Fallon". The Guardian. UK. 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- ^ А.Ю.Мазура (10 March 2015). "Заявление руководителя Делегации Российской Федерации на переговорах в Вене по вопросам военной безопасности и контроля над вооружениями". RF Foreign Ministry website.

- ^ Grove, Thomas (2015-03-10). "Russia says halts activity in European security treaty group". UK: Reuters. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ^ "From Russia with Menace". The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (1 April 2015). "Norway Reverts to Cold War Mode as Russian Air Patrols Spike". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Neil, "As Vladimir Putin Talks More Missiles and Might, Cost Tells Another Story", New York Times, June 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ "US announces new tank and artillery deployment in Europe". UK: BBC. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ "Nato shifts strategy in Europe to deal with Russia threat". UK: FT. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ a b "Putin says Russia beefing up nuclear arsenal, NATO denounces 'saber-rattling'". Reuters. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по итогам встречи министров обороны стран-членов НАТО the RF Foreign Ministry, 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Russia says NATO build-up on its borders is to achieve 'dominance in Europe'". RT. 27 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Steven Pifer, Fiona Hill. "Putin’s Risky Game of Chicken", New York Times, June 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Steven Pifer. Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling: What is he compensating for? 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Russian Program to Build World's Biggest Intercontinental Missile Delayed". The Moscow Times. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Statement of Foreign Ministers on the Readiness Action Plan NATO, 02 Dec 2014.

- ^ NATO condemns Russia, supports Ukraine, agrees to rapid-reaction force

- ^ "Nato shows its sharp end in Polish war games". UK: FT. 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ "Nato testing new rapid reaction force for first time". UK: BBC. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ "NATO to boost special defense forces to 40,000 - Stoltenberg". RF: RT. 2015-06-24. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ Robert S. Kravchuk, "Kuchma as Economic Reformer," Problems of Post-Communism Vol. 52#5 September–October 2005, pp 48–58

- ^ a b Taylor, Adam (4 September 2014). "That time Ukraine tried to join NATO — and NATO said no". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Guide to the EU deals with Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, BBC News (30 June 2014)

- ^ Traynor, Ian (28 November 2013). "Ukraine aligns with Moscow as EU summit fails". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Erastavi, Maxim (2 March 2014). "How Ukraine's Parliament Brought Down Yanukovych". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "U.S. and other powers kick Russia out of G8". CNN.com. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Johanna Granville, "The Folly of Playing High-Stakes Poker with Putin: More to Lose than Gain over Ukraine", May 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "G20: Canadian prime minister shirtfronts Vladimir Putin instead". The Guardian. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "G20 summit: Is Putin being frozen out? Russian president given a frosty reception in Brisbane over his Cold War-style stand-off with the West". Aljazeera. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Tony Abbott told Vladimir Putin to stop trying to 'recreate lost glories' during APEC 'shirtfront' meeting". ABC News. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Embattled Putin arrives at G20 with navy in tow". The Financial Times. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ "No prospects for Russia-US relations in near future — lawmaker". ITAR-TASS News Agency. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mackinnon, Mark (1 December 2014). "The new Cold War: Pro-Russian influence extends beyond Ukraine". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Zaks, Dmitry (23 December 2014). "Outraging Russia, Ukraine takes big step toward NATO". Yahoo. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (18 November 2014). "Merkel fears construction of Cold-War zones across Europe if Russia not given hard counter in Ukraine". National Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Toal, Gerard; O'Loughlin, John (20 March 2014). "How people in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria feel about annexation by Russia". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Higgins, Andrew (5 October 2014). "Tensions Surge in Estonia Amid a Russian Replay of Cold War Tactics". New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Penhaul, Karl (11 April 2014). "To Russia with love? Transnistria, a territory caught in a time warp". CNN. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (7 July 2014). "Eduard Shevardnadze, Foreign Minister Under Gorbachev, Dies at 86". New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (29 October 2013). "So Long, Saakashvili". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "Bush urging Nato expansion east". BBC News. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ a b Herszenhorn, David (24 November 2014). "Pact Tightens Russian Ties With Abkhazia". New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ McLaughlin, Daniel (25 November 2014). "West backs Georgia as Russia stokes new annexation fears". Irish Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi (26 February 2014). "Look West, Young Man: Georgia's 31-Year-Old Prime Minister Turns To Europe, Not Russia". Foreign Policy.com. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ a b Peter, Laurence (27 June 2014). "Guide to the EU deals with Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine". BBC News. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ a b Khojoyan, Sarah (4 August 2014). "New War Risk on Russian Fringe Amid Armenia-Azeri Clashes". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Paterson, Tony (1 April 2014). "Ukraine crisis: Nato 'to step up military cooperation with Russia's neighbours'". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (21 November 2013). "Ukraine suspends talks on EU trade pact as Putin wins tug of war". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ a b Herszenhorn, David (10 December 2014). "Armenia Wins Backing to Join Trade Bloc Championed by Putin". New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ "The Other EU". The Economist. 23 August 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Ciochina, Simon (21 December 2014). "Moldovan migrants denied re-entry to Russia". DeutscheWelle. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Morello, Carol; DeYoung, Karen (24 March 2014). "NATO general warns of further Russian aggression". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ http://uatoday.tv/society/estonia-stages-large-scale-independance-day-military-parade-on-russian-border-411526.html

- ^ a b Scrutton, Alistair; Johnson, Simon (20 October 2014). "Swedish 'Cold War' thriller exposes Baltic Sea nerves over Russia". Reuters. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Ritter, Karl; Huuhtanen, Matti (20 October 2014). "Submarine hunt sends Cold War chill across Baltic". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (2 April 2015). "Russia threatens to use 'nuclear force' over Crimea and the Baltic states". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "Putin threat of nuclear showdown over Baltics". The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Putin's war on the West". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Wagstyl, Stefan (27 November 2014). "Germany acts to counter Russia's Balkan designs". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b Czuczka, Tony; Parkin, Brian (21 November 2014). "Merkel Bids to Stall Putin Influence at EU's Balkan Edge". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Kosovo precedent for 200 territories—Lavrov, Tanjug/B92, January 23, 2008

- ^ "Putin's Reach: Merkel Concerned about Russian Influence in the Balkans". Spiegel. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Far-Right Europe Has a Crush on Moscow". Moscow Times. 25 November 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b Yardley, Jim; Becker, Jo (30 December 2014). "How Putin Forged a Pipeline Deal That Derailed". New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "From cold war to hot war". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ "In the Kremlin's pocket". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ "Hungarian protesters hit out at Orban's 'move towards Russia'". Yahoo News. 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (17 November 2014). "European leaders fear growth of Russian influence abroad". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Poland to build Russia border towers at Kaliningrad". BBC. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ "Poland border watchtowers 'planned'". The Independent. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ "Kaliningrad: European fears over Russian missiles". BBC. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Roth, Andrew (16 December 2013). "Deployment of Missiles Is Confirmed by Russia". New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Poland and U.S. Army hold joint air defence exercises near Warsaw

- ^ Prime Minister Đukanović: Protests in Podgorica supported by circles around Serbian Ortodox Church, and Russia

- ^ Montenegro Leader Accuses Russia of Supporting Opposition in His Country

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (19 November 2014). "The new cold war: are we going back to the bad old days?". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Levgold, Robert (July–August 2014). "Managing the New Cold War". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Rashid, Ahmed (15 August 2013). "Why, and What, You Should Know About Central Asia". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Going, going…". The Economist. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Nations without a cause". The Economist. 24 September 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Dyomkin, Dennis (10 December 2014). "Uzbek president asks Putin to help fight radical Islam in Central Asia". Reuters. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Wong, Kristina (21 March 2014). "Putin's quiet Latin America play". The Hill. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Trenin, Dmitri (15 July 2014). "Putin's Latin America trip aims to show Russia is more than just regional power". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Koren, Marina (27 March 2014). "Is Vladimir Putin Coming for the North Pole Next?". National Journal. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Rosen, Armin (25 June 2014). "Norway Wants NATO To Prepare For An Arctic Showdown". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Canadian jets intercepted Russian planes over Arctic". Toronto: The Star. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "View from Moscow: Syria Move Aimed at Ending International Isolation". Voice Of America. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "An odd way to make friends". The Economist. 10 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Putin Sees Path to Diplomacy Through Syria". The New York Times. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Putin Bids to End Russian Isolation With Syria Message to UN". Bloomberg. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "John McCain says US is engaged in proxy war with Russia in Syria". The Guardian. 4 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ ""The Russians have made a serious mistake": how Putin's Syria gambit will backfire". The VOA. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Russia Redefines Itself and Its Relations with the West", by Dmitri Trenin, The Washington Quarterly, Spring 2007

- ^ Buckley, Neil (19 September 2013). "Putin urges Russians to return to values of religion". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Matlack, Carol (4 June 2014). "Does Russia's Global Media Empire Distort the News? You Be the Judge". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Spiegel Staff (30 May 2014). "The Opinion-Makers: How Russia Is Winning the Propaganda War". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Tetrault-Farber, Gabrielle (12 May 2014). "Poll Finds 94% of Russians Depend on State TV for Ukraine Coverage". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Sindelar, Daisy (12 August 2014). "The Kremlin's Troll Army". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Gregory, Paul Roderick (9 December 2014). "Putin's New Weapon In The Ukraine Propaganda War: Internet Trolls". Forbes. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Dejevsky, Mary (11 April 2014). "News of a Russian arms buildup next to Ukraine is part of the propaganda war". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ "A new propaganda war underpins the Kremlin's clash with the West". The Economist. 29 March 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Kruscheva, Nina (29 July 2014). "Putin's anti-American rhetoric now persuades his harshest critics". Reuters. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "A clampdown on foreign-owned media is an opportunity for some oligarchs". The Economist. 8 November 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (15 October 2014). "Russia's Putin signs law extending Kremlin's grip over media". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Peron, Laetitia (20 November 2014). "Russia fights Western 'propaganda' as critical media squeezed". Yahoo News. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Pomerantsev, Peter (9 September 2014). "Russia and the Menace of Unreality". The Atlantic. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ Seputyte, Milda (16 January 2015). "Four EU Countries Propose Steps to Counter Russia's Propaganda". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Mogherini: EU may establish Russian-language media". Reuters. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Mamlyuk, Boris (9 July 2015). "The Ukraine Crisis, Cold War II, and International Law". Social Science Research Network. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ "Russian spies 'at Cold War level'". BBC. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Spying at Cold War Levels, U.S. Says". The Moscow Times. 30 March 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Russian spies in UK 'at cold war levels', says MI5". The Guardian. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "US intelligence spending has doubled since 9/11, top secret budget reveals". The Guardian. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/10/27/us-czech-russia-espionage-idUSKBN0IG17B20141027

- ^ Braw, Elisabeth (10 December 2014). "Russian Spies Return to Europe in 'New Cold War'". Newsweek. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Former CIA Spies Call 'The Americans' More Exciting Than Reality". U.S. News & World Report. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "How the U.S. thinks Russians hacked the White House". CNN. 8 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ G20 summit: Brics build momentum to challenge G7 ′′The Telegraph′′, 30 Nov 2014.

- ^ 2014 nominal GDP (in trillions of US Dollars) and nominal GDP per capita figures by the IMF

- ^ Adomanis, Mark (31 December 2013). "7 Reasons That Russia Is Not The Soviet Union". Forbes. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Klapper, Bradley (3 February 2015). "New Cold War: US, Russia fight over Europe's energy future". Yahoo. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Finn, Peter (2007-11-03). "Russia's State-Controlled Gas Firm Announces Plan to Double Price for Georgia". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

LNeywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Chiara Albanese and Ben Edwards (9 October 2014). "Russian Companies Clamor for Dollars to Repay Debt". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ a b Chung, Frank (18 December 2014). "The Cold War is back, and colder". News.au. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Oil Plunge Part of US Campaign to Destabilize Russia

- ^ Smolchenko, Anna (13 October 2014). "China, Russia seek 'international justice', agree currency swap line". news.yahoo.com. AFP News. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Russian Food Prices Stabilize After Months of Racing Inflation

- Articles to be split from November 2015

- Cold War II

- 2013–15 Ukrainian crisis

- 21st-century conflicts

- Foreign relations of the European Union

- Foreign relations of China

- China–Russia relations

- 21st century in Europe

- 21st century in Russia

- Foreign relations of Russia

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Geopolitical rivalry

- History of Russia (1992–present)

- NATO–Russia relations

- Russia–European Union relations

- Russia–United States relations

- Vladimir Putin