Lisu people: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

===Migration into Arunachal Pradesh=== |

===Migration into Arunachal Pradesh=== |

||

Christian Lisu in Arunachal Pradesh are believed to have migrated from the [[Patkai]] Hills. Part of the population was believed to have migrated from China to [[Burma]], fleeing the [[Communists]], and then were ordered to leave Burma by the government at the time; this group also settled in Arunachal Pradesh. In Arunachal Pradesh, they are primarily concentrated in [[Changlang District]] and [[Tirap district]].<ref>[http://changlang.nic.in/changlang.html#people/ People]</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Contributions to Sino-Tibetan Studies|author=John McCoy, Timothy Light|publisher=BRILL|pages=915–6|year=39|isbn=9004078509}}</ref> |

Christian Lisu in [[Arunachal Pradesh|Arunachal Pradesh, India]] are believed to have migrated from the [[Patkai]] Hills. Part of the population was believed to have migrated from China to [[Burma]], fleeing the [[Communists]], and then were ordered to leave Burma by the government at the time; this group also settled in Arunachal Pradesh. In Arunachal Pradesh, they are primarily concentrated in [[Changlang District]] and [[Tirap district]].<ref>[http://changlang.nic.in/changlang.html#people/ People]</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Contributions to Sino-Tibetan Studies|author=John McCoy, Timothy Light|publisher=BRILL|pages=915–6|year=39|isbn=9004078509}}</ref> |

||

==Culture== |

==Culture== |

||

Revision as of 10:58, 23 April 2009

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| China(Yunnan,Sichuan)[1], Thailand, Burma, India | |

| Languages | |

| Lisu | |

| Religion | |

| Animism,Christianity |

The Lisu people (Chinese: 傈僳族 : lìsù zú) are a Tibeto-Burman ethnic group who inhabit the mountainous regions of Burma (Myanmar), Southwest China, Thailand, and the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

About 730,000 live in Lijiang, Baoshan, Nujiang and Dehong prefectures in the Yunnan Province of China. The Lisu form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. In Burma, the Lisu are known as one of the seven Kachin minority groups and an estimated population of 350,000 Lisu live in Kachin and Shan State in Burma. Approximately 55,000 live in Thailand, where they are one of the six main hill tribes. They mainly inhabit the remote country areas[citation needed].

History

Lisu history is passed from one generation to the next in the form of songs. Today, this song is so long that it can take a whole night to sing.[1]

Origins

The Lisu are believed to originate from eastern Tibet. Research done by Lisu scholars indicates that they moved to northwestern Yunnan. They inhabited a region across Baoshan and the Tengchong plain for thousands of years. The Lisu, Lahu, Akha and Kachin languages are Tibetan-Burman languages, distantly related to Burmese and Tibetan.[2] [3] [4] [5] After the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty, around 1140-1644 A.D. the eastern and Southern Lisu language and culture were greatly influenced by Han culture of China.[6] [7] Taiping village in Yinjiang, Yunnan, China, was first established by Lu Shi Lisu people about 1000 years ago[citation needed]. In the mid-19th century, Lisu peoples in Yinjiang began moving into Momeik, Burma, a population of Southern Lisu moved into Mogok, north-eastern Burma, and then in the late 19th century, moved into northern Thailand.[8] [9] [10] [7]

Migration into Arunachal Pradesh

Christian Lisu in Arunachal Pradesh, India are believed to have migrated from the Patkai Hills. Part of the population was believed to have migrated from China to Burma, fleeing the Communists, and then were ordered to leave Burma by the government at the time; this group also settled in Arunachal Pradesh. In Arunachal Pradesh, they are primarily concentrated in Changlang District and Tirap district.[11][12]

Culture

The Lisu tribe consists of more than 58 different clans. Each family clan has its own name or surname. The biggest family clans well known among the tribe clans are Laemae pha (Shue or The Grass), Bya pha (The Bee), Thorne pha, Ngwa Pha (Fish), Naw pha (Thou or Bean), Seu pha ( the Woods), Khaw pha. Most of the family names came from their own work as hunters in the primitive time. However, later, they adopted many Chinese family names[citation needed].

After the Ming Dynasty, most Lisu tribe people had become a people that lived in villages high in the mountains or in mountain valleys. However, those who still lived in the Paoshan plains, standing on the side of the Qing Dynasty, fought against the kingdom of Ming. The Lisu knife ladder climbing festival was first held as a memorial event of victory over Ming in 1644 A.D. The Lisu people invented their own traditional dance so called "che-ngoh-che" along with the Lisu guitar which has no bars on the fretboard. They invented another musical instrument called fulu jewlew as well. It is a kind of flute that has about six or seven small bamboo tubes tied up together to a dried-hollow-gourd.[citation needed] Songs and dances are different from each other according to the occasions. They have different songs and dances for weddings, homecoming hunters, harvest time and so on, separately.

Lisu villages are usually built close to water to provide easy access for washing and drinking.[6] Their homes are usually built on the ground and have dirt floors and bamboo walls, although an increasing number of the more affluent Lisu are now building houses from wood or even concrete.[1]

Lisu subsistence was based on paddy fields, mountain rice, fruit and vegetables. However, they have typically lived in ecologically fragile regions that do not easily support subsistence. They also faced constant upheaval from both physical and social disasters (earthquakes and landslides; wars and governments). Therefore, they have typically been dependent on trade for survival. This included work as porters and caravan guards. With the introduction of the opium poppy as a cash crop in the early 19th century, many Lisu populations were able to achieve economic stability. This lasted for over 100 years, but opium production has all but disappeared in Thailand and China due to interdiction of production. Very few Lisu ever used opium, or its more common derivative heroin, except for medicinal use by the elders to alleviate the pain of arthritis.[13]

The Lisu practiced swidden (slash and burn) horticulture. In conditions of low population density where land can be fallowed for many years, swiddening is an environmentally sustainable form of horticulture. Despite decades of swiddening by hill tribes such as the Lisu, northern Thailand had a higher proportion of intact forest than any other part of Thailand. However, with road building by the state, logging (some legal but mostly illegal) by Thai companies,[14] [15] enclosure of land in national parks, and influx of immigrants from the lowlands, swidden fields can not be fallowed, can not re-grow, and swiddening results in large swathes of deforested mountainsides. Under these conditions, Lisu and other swiddeners have been forced to turn to new methods of agriculture to sustain themselves.[16]

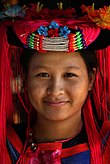

Perhaps the best-known subgroup of the Lisu is the Flowery Lisu in Thailand, due to hill tribe tourism. Lisu women are remarked for their brightly colored dress. They wear a multi-colored knee-length tunics of red, blue or green with a wide black belt and blue or black pants. Sleeve shoulders and cuffs are decorated with a dense applique of narrow horizontal bands of blue, red and yellow. Men wear baggy pants, usually in bright colors but normally wear a more western type of shirt or top.

Religion

Animism, shamanism, ancestor worship

There is little published material (besides that of Christian missionaries) regarding the religious practices of the Lisu, but it is known that most Lisu still practice a religion that is part animistic, part ancestor worship, but is mixed within complex local systems of place-based religion. Most important rituals are performed by shamans. The main Lisu Festival corresponds to the Chinese New Year and is celebrated with music, feasting and drinking, as are weddings; people wear large amounts of silver jewelry and wear their best clothes at these times. In each traditional village there is a sacred grove at the top of the village, where the sky spirit (or god) and other main spirits are presented with offerings for propitiation; each house has an ancestor altar at the back of the house. [17][18][19]

Christianity

Beginning in the 20th century, some Lisu people in China and Burma converted to Christianity. Missionaries such as James O. Fraser and Isobel Kuhn of the China Inland Mission, were active with the Lisu of Yunnan[20]. The Chinese government's Religious Affairs Bureau has proposed considering Christianity as the official religion of the Lisu.[21] According to estimates by the Christian organization OMF International, as of 2008 there are now at least 300,000 Christian Lisu in Yunnan, China and 150,000 in Burma (between 40-50% of the Lisu population of each country). The Lisu of Thailand have remained largely unchanged by Christian influences[22][23].

Language

Linguistically, the Lisu belong to the Yi branch of the Sino-Tibetan family.

There are two scripts in use and the Chinese Department of Minorities publishes literature in both. The oldest and most widely used one is the Fraser alphabet developed about 1920 by James O. Fraser and the Karen evangelist Ba Taw. The second script was developed by the Chinese government and is based on pinyin.

Today the Lisu in Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture have their own language, but Lisu elsewhere speak the local language.

Fraser's script for the Lisu language was used to prepare the first published works in Lisu which were a catechism, portions of Scripture, and eventually, with much help from his colleagues, a complete New Testament in 1936. In 1992, the Chinese government officially recognized the Fraser alphabet as the official script of the Lisu language.[24]

Only a small portion of Lisu are actually able to read or write the script[citation needed], with most learning to read and write the local language (Chinese, Thai, Burmese) through primary education[citation needed].

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Hutheesing 1990

- ^ Gros 1996

- ^ Gros 2001

- ^ Bradley 1997

- ^ Matisoff 1986

- ^ a b Dessaint 1972

- ^ a b Hanks & Hanks 2001

- ^ George 1915

- ^ Enriquez 1921

- ^ Scott & Hardiman 1900-1901

- ^ People

- ^ John McCoy, Timothy Light (39). Contributions to Sino-Tibetan Studies. BRILL. pp. 915–6. ISBN 9004078509.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Durrenberger 1976

- ^ Fox 2000

- ^ Fox et al. 1995

- ^ McCaskill and Kempe 1997

- ^ Durrenberger 1989

- ^ Bradley (1999), p. 89

- ^ Klein-Hutheesing 1990

- ^ "Yunnan Province of China Government Web". Retrieved 2008–02–15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Covell, Ralph (2008). "To Every Tribe". Christian History & Biography (98): 27–28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Lisu of China". OMF International. Retrieved 2008–02–20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ OMF International (2007), p. 1-2

- ^ "Omniglot writing systems & languages of the world". Fraser alphabet. Retrieved 2008–02–20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

References

- Bradley, David (1999). Hill Tribes Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. ISBN 0864426356.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - OMF International (2007). Global Chinese Ministries. Littleton, Colorado: OMF International.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gros, Stephane, 1996. Terres de confins, terres de colonisation: essay sur les marches Sino-Tibetaines due Yunnan a travers l'implantation de la Mission du Tibet, Peninsule 33(2): 147-211.

- Gros, Stephane, 2001. Ritual and politics: missionary encounters in local culture in northwest Yunnan, In Legacies and Social Memory, panel at the Association for Asian Studies, March 22-25, 2001.

- Bradley, David, 1997. What did they eat? Grain crops of Burmic groups, Mon-Khmer Studies 27: 161-170.

- Dessaint, Alain Y, 1972. Economic organization of the Lisu of the Thai highlands Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology, University of Hawaii.

- Hanks, Jane R. and Lucien M. Hanks, 2001. Tribes of the northern Thailand frontier, Yale Southeast Studies Monographs, Volume 51, New Haven, Hanks.

- Enriquez, Major C.M., 1921. The Yawyins or Lisu, Journal of the Burma Research Society 11 (Part 2), pp. 70-74.

- George, E.C.S., 1915. Ruby Mines District, Burma Gazetteer, Rangoon, Office of the Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma.

- Scott, James George and J.P. Hardiman, 1900-1901. Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, Parts 1 & 2, reprinted by AMS Press (New York).

- Hutheesing, Otome Klein, 1990. Emerging Sexual Inequality Among the Lisu of Northern Thailand: The Waning of Elephant and Dog Repute, E.J. Brill, New York and Leiden.

- Durrenberger, E. Paul, 1976. The economy of a Lisu village, American Ethnologist 32: 633-644.

- Fox, Jefferson M., 2000. How blaming 'slash and burn' farmers is deforesting mainland Southeast Asia, AsiaPacific Issues No. 47.

- Fox, Krummel, Yarnasarn, Ekasingh, and Podger, 1995. Land use and landscape dynamics in northern Thailand: assessing change in three upland watersheds, Ambio 24 (6): 328-334.

- McCaskill, Don and Ken Kampe, 1997. Development or domestication? Indigenous peoples of Southeast Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

- Durrenberger, E. Paul, 1989. Lisu Religion, Southeast Asia Publications Occasional Papers No. 13, DeKalb: Northern Illinois University.

Further reading

- Tribes of the northern Thailand frontier, Yale Southeast Studies Monographs, Volume 51, New Haven, Hanks, Jane R. and Lucien M. Hanks, 2001.

- Emerging Sexual Inequality Among the Lisu of Northern Thailand: The Waning of Elephant and Dog Repute, Hutheesing, Otome Klein, E.J. Brill, 1990

- The economy of a Lisu village, E. Paul Durrenberger, American Ethnologist 32: 633-644, 1976

- Lisu Religion, E. Paul Durrenberger, Northern Illinois University Southeast Asia Publications No. 12, 1989.

- Behind The Ranges: Fraser of Lisuland S.W. China by Mrs. Howard Taylor (Mary Geraldine Guinness)

- Mountain Rain by Eileen Fraser Crossman

- A Memoir of J. O. Fraser by Mrs. J. O. Fraser

- James Fraser and the King of the Lisu by Phyllis Thompson

- The Prayer of Faith by James O. Fraser & Mary Eleanor Allbutt

- In the Arena, Kuhn, Isobel OMF Books (1995)

- Stones of Fire, Kuhn, Isobel Shaw Books (June 1994)

- Ascent to the Tribes: Pioneering in North Thailand, Kuhn, Isobel OMF Books (2000)

- Precious Things of the Lasting Hills, Kuhn, Isobel OMF Books (1977)

- Second Mile People, Kuhn, Isobel Shaw Books (December 1999)

- Nests Above the Abyss, Kuhn, Isobel Moody Press (1964)

- The Dogs May Bark, but the Caravan Moves On, Morse, Gertrude College Press, (1998)

- Transformations of Lisu social structure under opium control and watershed conservation in northern Thailand, Gillogly, Kathleen A. PhD thesis, Anthropology, University of Michigan. 2006. Available as open access at http://manao.manoa.hawaii.edu/38/.