Muammar Gaddafi: Difference between revisions

Asserghozlan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

→Early life: Studies in Athens |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

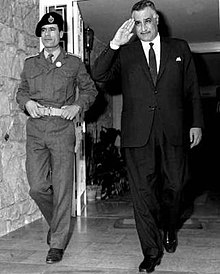

Gaddafi was born in a [[Bedouin]] family near [[Sirt]]. As a teenager, Gaddafi was an admirer of Egyptian President [[Gamal Abdel Nasser]] and his [[Arab socialism|Arab socialist]] and nationalist ideology. Gaddafi took a part in anti-Israel demonstrations during the 1956 [[Suez Crisis]]. |

Gaddafi was born in a [[Bedouin]] family near [[Sirt]]. As a teenager, Gaddafi was an admirer of Egyptian President [[Gamal Abdel Nasser]] and his [[Arab socialism|Arab socialist]] and nationalist ideology. Gaddafi took a part in anti-Israel demonstrations during the 1956 [[Suez Crisis]]. |

||

An early conspirator, he began his first plan to overthrow the monarchy while in military college. He received further military training in the [[United Kingdom]].<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk">{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7594790.stm |publisher=BBC News | title=Profile: Muammar Gaddafi | date=28 August 2009 | accessdate=13 May 2010 | first=Aidan | last=Lewis}}</ref> |

An early conspirator, he began his first plan to overthrow the monarchy while in military college. He received further military training in [[Hellenic Military Academy]] in [[Athens]], [[Greece]]<ref>Greek newspaper "Ta Nea" (Τα Νέα),21 Feb. 2011[http://www.tanea.gr/default.asp?pid=2&ct=2&artid=4619247 ΜΟΥΑΜΑΡ ΚΑΝΤΑΦΙ 42 ΧΡΟΝΙΑ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΞΟΥΣΙΑ]</ref><ref>athens.indymedia.org[http://athens.indymedia.org/front.php3?lang=el&article_id=170596 ΓΙΑΤΙ ΟΙ ΛΥΒΙΟΙ ΘΕΛΟΥΝ ΤΟΝ ΚΑΝΤΑΦΙ]</ref> and the [[United Kingdom]].<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk">{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7594790.stm |publisher=BBC News | title=Profile: Muammar Gaddafi | date=28 August 2009 | accessdate=13 May 2010 | first=Aidan | last=Lewis}}</ref> |

||

==In power== |

==In power== |

||

Revision as of 01:32, 22 February 2011

This article is about a person involved in a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (February 2011) |

Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi[see below] (Template:Lang-ar Muʿammar al-Qaḏḏāfī ; also known simply as Colonel Gaddafi; born 7 June 1942) has been the de facto leader of Libya since a coup in 1969.[1] He is currently desperately clinging onto power in wake of the 2011 Libyan protests, having reportedly ordered the army to bomb and kill anti-government protestors.

From 1972, when Gaddafi relinquished the title of prime minister, he has been accorded the honorifics "Guide of the First of September Great Revolution of the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" or "Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official press.[2] With the death of Omar Bongo of Gabon on 8 June 2009, he became the longest serving of all current non-royal national leaders and he is one of the longest serving rulers in history. He is also the longest-serving ruler of Libya since Libya, then Tripoli, became an Ottoman province in 1551.[3]

Early life

Gaddafi was born in a Bedouin family near Sirt. As a teenager, Gaddafi was an admirer of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Arab socialist and nationalist ideology. Gaddafi took a part in anti-Israel demonstrations during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

An early conspirator, he began his first plan to overthrow the monarchy while in military college. He received further military training in Hellenic Military Academy in Athens, Greece[4][5] and the United Kingdom.[6]

In power

Military coup d'état

On 1 September 1969, a small group of junior military officers led by Gaddafi staged a bloodless coup d'état against King Idris, while he was in Turkey for medical treatment. His nephew, the Crown Prince Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida al-Mahdi as-Sanussi, had been formally deposed by the revolutionary army officers and put under house arrest; they abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic.[7] The slim 27-year-old Gaddafi, with a taste for safari suits and sunglasses, then sought to become the new "Che Guevara of the age".[8] To accomplish this Gaddafi turned Libya into a haven for anti-Western radicals, where any group, supposedly, could receive weapons and financial assistance, provided they claimed to be fighting imperialism.[8] The Italian population in Libya almost disappeared after Gaddafi ordered the expulsion of Italians in 1970.[9]

A Revolutionary Command Council was formed to rule the country, with Gaddafi as chairman. He added the title of prime minister in 1970, but gave up this title in 1972. Unlike some other military revolutionaries, Gaddafi did not promote himself to the rank of general upon seizing power, but rather accepted a ceremonial promotion from captain to colonel and has remained at this rank since then. While at odds with Western military ranking for a colonel to rule a country and serve as Commander-in-Chief of its military, in Gaddafi's own words Libya's society is "ruled by the people", so he needs no more grandiose title or supreme military rank.[1]

Islamic socialism and pan-Arabism

Gaddafi based his new regime on a blend of Arab nationalism,[10][11] aspects of the welfare state,[12][13][14] and what Gaddafi termed "popular democracy",[15] or more commonly "direct, popular democracy". He called this system "Islamic socialism", and, while he permitted private control over small companies, the government controlled the larger ones. Welfare, "liberation" (or “emancipation” depending on the translation),[16] and education[17] were emphasized. He also imposed a system of Islamic morals,[18][19] outlawing alcohol and gambling. Like previous revolutionary figures of the 20th century such as Mao and his Little Red Book, Gaddafi outlined his political philosophy in his Green Book to reinforce the ideals of this socialist-Islamic state and published in three volumes between 1975 and 1979.[citation needed]

In 1977, Gaddafi proclaimed that Libya was changing its form of government from a republic to a "jamahiriya" – a neologism that means "mass-state" or "government by the masses". In theory, Libya became a direct democracy governed by the people[20] through local popular councils and communes.[21] At the top of this structure was the General People's Congress,[22] with Gaddafi as secretary-general. However, after only two years, Gaddafi gave up all of his governmental posts in keeping with the new egalitarian philosophy.[citation needed]

From time to time, Gaddafi has responded to domestic and external opposition with violence. His revolutionary committees called for the assassination of Libyan dissidents living abroad in April 1980, with Libyan hit squads sent abroad to murder them. On 26 April 1980, Gaddafi set a deadline of 11 June 1980 for dissidents to return home or be "in the hands of the revolutionary committees".[23] Nine Libyans were murdered during that time, five of them in Italy.[citation needed]

External relations

With respect to Libya's neighbors, Gaddafi followed Gamal Abdel Nasser's ideas of pan-Arabism and became a fervent advocate of the unity of all Arab states into one Arab nation. He also supported pan-Islamism, the notion of a loose union of all Islamic countries and peoples. After Nasser's death on 28 September 1970, Gaddafi attempted to take up the mantle of ideological leader of Arab nationalism. He proclaimed the "Federation of Arab Republics" (Libya, Egypt, and Syria) in 1972, hoping to create a pan-Arab state, but the three countries disagreed on the specific terms of the merger. In 1974, he signed an agreement with Tunisia's Habib Bourguiba on a merger between the two countries, but this also failed to work in practice and ultimately differences between the two countries would deteriorate into strong animosity.

Libya was also involved in a sometimes violent territorial dispute with neighbouring Chad over the Aouzou Strip, which Libya occupied in 1973. This dispute eventually led to the Libyan invasion of the country and to a conflict that was ended by a ceasefire reached in 1987. The dispute was in the end settled peacefully in June 1994 when Libya withdrew troops from Chad due to a judgement of the International Court of Justice issued on 13 February 1994.[24]

Gaddafi also became a strong supporter of the Palestine Liberation Organization, which support ultimately harmed Libya's relations with Egypt, when in 1979 Egypt pursued a peace agreement with Israel. As Libya's relations with Egypt worsened, Gaddafi sought closer relations with the Soviet Union. Libya became the first country outside the Soviet bloc to receive the supersonic MiG-25 combat fighters, but Soviet-Libyan relations remained relatively distant. Gaddafi also sought to increase Libyan influence, especially in states with an Islamic population, by calling for the creation of a Saharan Islamic state and supporting anti-government forces in sub-Saharan Africa.

Notable in Gaddafi's politics has been his support for self-styled liberation movements, and also his sponsorship of rebel movements in West Africa, notably Sierra Leone and Liberia, as well as Muslim groups. In the 1970s and the 1980s, this support was sometimes so freely given that even the most unsympathetic groups could obtain Libyan support; often the groups represented ideologies far removed from Gaddafi's own. Gaddafi's approach often tended to confuse international opinion.

Throughout the 1970s, his regime was implicated in subversion and terrorist activities in both Arab and non-Arab countries. By the mid-1980s, he was widely regarded in the West as the principal financier of international terrorism. Reportedly, Gaddafi was a major financier of the "Black September Movement" which perpetrated the Munich massacre at the 1972 Summer Olympics, and was accused by the United States of being responsible for direct control of the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing that killed three people and wounded more than 200, of whom a substantial number were U.S. servicemen. He is also said to have paid "Carlos the Jackal" to kidnap and then release a number of Saudi Arabian and Iranian oil ministers.[citation needed]

For his anti western policy, Gaddafi gained a negative reputation in western media and diplomatic circles. Referring to his criticism of moderate and pro-western Arab leaders, a US diplomat in 1974 has remarked:

While he and his regime do not have reputation among Libyans for spilling blood, we suspect this zealot is capable of justifying in his own mind any attempt to assassinate [Egyptian President] Sadat.[25]

On the other hand, Egyptian diplomat Omar Hefni Mahmoud, at a private conversation, characterized Gaddafi as

brash "pure" young man who had not become corrupted by politics yet.[26]

However, in 1976 another US diplomat referred to Gaddafi as

a more practical and pragmatic politician than we had given him credit for.[27]

Tensions between Libya and the West reached a peak during the Ronald Reagan administration, which tried to overthrow Gaddafi. The Reagan administration viewed Libya as a belligerent rogue state because of its uncompromising stance on Palestinian independence, its support for revolutionary Iran in the 1980–1988 war against Saddam Hussein's Iraq (see Iran–Iraq War), and its backing of "liberation movements" in the developing world. Reagan himself dubbed Gaddafi the "mad dog of the Middle East". In December 1981, the US State Department invalidated US passports for travel to Libya, and in March 1982, the U.S. declared a ban on the import of Libyan oil[28] and the export to Libya of U.S. oil industry technology; European nations did not follow suit. Libya has also been a supporter of the Polisario Front in their fight against Spanish colonialism and Moroccan military occupation.

In 1984, British police constable Yvonne Fletcher was shot outside the Libyan Embassy in London while policing an anti-Gaddafi demonstration. A burst of machine-gun fire from within the building was suspected of killing her, but Libyan diplomats asserted their diplomatic immunity and were repatriated. The incident led to the breaking off of diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Libya for over a decade.[29]

The U.S. attacked Libyan patrol boats from January to March 1986 during clashes over access to the Gulf of Sidra, which Libya claimed as territorial waters. On 15 April 1986, Ronald Reagan ordered major bombing raids, dubbed Operation El Dorado Canyon, against Tripoli and Benghazi killing 45 Libyan military and government personnel as well as 15 civilians.[1] This strike followed U.S. interception of telex messages from Libya's East Berlin embassy suggesting Libyan government involvement in a bomb explosion on 5 April in West Berlin's La Belle discothèque, a nightclub frequented by U.S. servicemen. Among the alleged fatalities of 15 April retaliatory attack by the U.S. was Gaddafi's adopted daughter, Hannah. Libya responded by firing two Scud missiles at the U.S. Coast Guard navigation station on the Italian island of Lampedusa. The missiles landed in the sea, and caused no damage.[citation needed]

In late 1987, a merchant vessel, the MV Eksund, was intercepted. Destined for the IRA, a large consignment of arms and explosives supplied by Libya was recovered from the Eksund. British intelligence believed this was not the first and that Libyan arms shipments had previously reached the IRA. (See Provisional IRA arms importation.) It has also been alleged that Qaddafi was exporting weapons to the FARC rebel group in Colombia.

For most of the 1990s, Libya endured economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation as a result of Gaddafi's refusal to allow the extradition to the United States or Britain of two Libyans accused of planting a bomb on Pan Am Flight 103, which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland. Through the intercession of South African President Nelson Mandela – who made a high-profile visit to Gaddafi in 1997 – and UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, Gaddafi agreed in 1999 to a compromise that involved handing over the defendants to the Netherlands for trial under Scottish law.:[30] UN sanctions were thereupon suspended, but U.S. sanctions against Libya remained in force.

An alleged plot by Britain's secret intelligence service to assassinate Colonel Gaddafi, when rebels attacked Gaddafi's motorcade near the city of Sirte in February 1996, was described as "pure fantasy" by former foreign secretary Robin Cook, although the FCO later admitted: "We have never denied that we knew of plots against Gaddafi."[31]

In August 2003, two years after Abdelbaset al-Megrahi's conviction, Libya wrote to the United Nations formally accepting 'responsibility for the actions of its officials' in respect of the Lockerbie bombing and agreed to pay compensation of up to US$2.7 billion – or up to US$10 million each – to the families of the 270 victims. The same month, Britain and Bulgaria co-sponsored a UN resolution which removed the suspended sanctions. (Bulgaria's involvement in tabling this motion led to suggestions that there was a link with the HIV trial in Libya in which 5 Bulgarian nurses, working at a Benghazi hospital, were accused in 1998 of infecting 426 Libyan children with HIV.)[32] Forty percent of the compensation was then paid to each family, and a further 40% followed once U.S. sanctions were removed. Because the U.S. refused to take Libya off its list of state sponsors of terrorism, Libya retained the last 20% ($540 million) of the $2.7 billion compensation package. In October 2008 Libya paid $1.5 billion into a fund which will be used to compensate relatives of the

- Lockerbie bombing victims with the remaining 20%;

- American victims of the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing;

- American victims of the 1989 UTA Flight 772 bombing; and,

- Libyan victims of the 1986 US bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi.

As a result, President Bush signed Executive Order 13477 restoring the Libyan government's immunity from terror-related lawsuits and dismissing all of the pending compensation cases in the US, the White House said.[33]

On 28 June 2007, Megrahi was granted the right to a second appeal against the Lockerbie bombing conviction.[34] One month later, the Bulgarian medics were released from jail in Libya. They returned home to Bulgaria and were pardoned by Bulgarian president, Georgi Parvanov.

Gaddafi's 2009 welcome to the return of convicted Lockerbie bomber Megrahi, who was released from prison on compassionate grounds, attracted criticism from Western leaders[35][36][37] and has disrupted his first-ever visit to the United States to attend a UN General Session. Gaddafi often resides in a tent when travelling.[38] His plans to erect a tent in Central Park and on Libyan government property in Englewood, New Jersey during Gaddafi's stay at the UN were both protested by community leaders and subsequently cancelled by Gaddafi.[39][40][41] His tent finally found a home on an estate belonging to Donald Trump in Bedford.[42]

23 September 2009 marked Gaddafi's first appearance at the United Nations General Assembly where he addressed world leaders at the annual gathering in New York. The Libyan leader while demanding representation for the African Union, used the occasion to scold the United Nations structure saying the 15-member body practised “security feudalism” for those who had a protected seat.[43] The Libyan leader's appearance at the United Nations generated demonstrations both for and against Gaddafi.[44]

Openness

"In his four decades as Libya's 'Brother Leader', Colonel Muammar Gaddafi has gone from being the epitome of revolutionary chic to an eccentric statesman with entirely benign relations with the West."

Gaddafi also appeared to be attempting to improve his image in the West. Two years prior to the 11 September 2001 attacks, Libya pledged its commitment to fighting al-Qa'ida and offered to open up its weapons programme to international inspection. The Bush administration did not pursue the offer at the time since Libya's weapons program was not then regarded as a threat, and the matter of handing over the Lockerbie bombing suspects took priority. Following the attacks of 11 September, Gaddafi made one of the first, and firmest, denunciations of the Al-Qaeda bombers by any Muslim leader. Gaddafi also appeared on ABC for an open interview with George Stephanopoulos, a move that would have seemed unthinkable less than a decade earlier.

Following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein by US forces in 2003, Gaddafi announced that his nation had an active weapons of mass destruction program, but was willing to allow international inspectors into his country to observe and dismantle them. US President George W. Bush and other supporters of the Iraq War portrayed Gaddafi's announcement as a direct consequence of the Iraq War by stating that Gaddafi acted out of fear for the future of his own regime if he continued to keep and conceal his weapons. Italian Premier Silvio Berlusconi, a supporter of the Iraq War, was quoted as saying that Gaddafi had privately phoned him, admitting as much. Many foreign policy experts, however, contend that Gaddafi's announcement was merely a continuation of his prior attempts at normalizing relations with the West and getting the sanctions removed. To support this, they point to the fact that Libya had already made similar offers starting four years prior to it finally being accepted.[45][46] International inspectors turned up several tons of chemical weaponry in Libya, as well as an active nuclear weapons program. As the process of destroying these weapons continued, Libya improved its cooperation with international monitoring regimes to the extent that, by March 2006, France was able to conclude an agreement with Libya to develop a significant nuclear power program.

In March 2004, British PM Tony Blair became one of the first Western leaders in decades to visit Libya and publicly meet Gaddafi. Blair praised Gaddafi's recent acts, and stated that he hoped Libya could now be a strong ally in the international War on Terrorism. In the run-up to Blair's visit, the British ambassador in Tripoli, Anthony Layden, explained Libya's and Gaddafi's political change thus:

- "35 years of total state control of the economy has left them in a situation where they're simply not generating enough economic activity to give employment to the young people who are streaming through their successful education system. I think this dilemma goes to the heart of Colonel Gaddafi's decision that he needed a radical change of direction."[47]

On 15 May 2006, the US State Department announced that it would restore full diplomatic relations with Libya, once Gaddafi declared he was abandoning Libya's weapons of mass destruction program. The State Department also said that Libya would be removed from the list of nations supporting terrorism.[48] On 31 August 2006, however, Gaddafi openly called upon his supporters to "kill enemies" of his revolution and anyone who asks for political change within Libya.[49]

In July 2007, French president Nicolas Sarkozy visited Libya and signed a number of bilateral and multilateral (EU) agreements with Gaddafi.[50]

On 4 March 2008 Gaddafi announced his intention to dissolve the country's existing administrative structure and disburse oil revenue directly to the people. The plan includes abolishing all ministries, except those of defence, internal security, and foreign affairs, and departments implementing strategic projects.[51]

In September 2008, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice visited Libya and met with Gaddafi as part of a North African tour. This was the first visit to Libya by a US Secretary of State since 1953.[52]

In January 2009, Gaddafi contributed an editorial to the New York Times, suggesting that he was in favor of a single-state solution to the Israeli and Palestinian conflicts that moved beyond old conflicts and looked to a unified future of shared culture and mutual respect.[53]

Cooperation with Italy

On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi signed a historic cooperation treaty in Benghazi.[54][55][56] Under its terms, Italy will pay $5 billion to Libya as compensation for its former military occupation. In exchange, Libya will take measures to combat illegal immigration coming from its shores and boost investments in Italian companies.[55][57] The treaty was ratified by Italy in 6 February 2009,[54] and by Libya on 2 March, during a visit to Tripoli by Berlusconi.[55][58] In June Gaddafi made his first visit to Rome, where he met Prime Minister Berlusconi, President Giorgio Napolitano and Senate President Renato Schifani; Chamber President Gianfranco Fini cancelled the meeting because of Gaddafi's delay.[55] The Democratic Party and Italy of Values opposed the visit,[59][60] and many protests were staged throughout Italy by human rights organizations and the Radical Party.[61] Gaddafi also took part in the G8 summit in L'Aquila in July as Chairman of the African Union.[55] During the summit a handshake between US President Barack Obama and Muammar Gaddafi took place (the first time the Libyan leader has been greeted by a serving US president),[62] then at summit's official dinner offered by Italian President Giorgio Napolitano US and Libyan leaders upset the ceremony and sat by the Italian Prime Minister and G8 host, Silvio Berlusconi. (According to ceremony, Gaddafi should seat three places after Berlusconi).[63][64][65][66][67] During a two-day visit to Italy in August 2010 Gaddafi upset his hosts by stating that Europe should convert to Islam. It was during a lecture in front of 200 young women whom Gaddafi had paid a modeling agency to attend that he urged the women to convert to Islam and according to one of them said, "Islam should become the religion of all of Europe." Each of the women was given a copy of the Qur'an.[68]

Pan-Africanism

Gaddafi has also emerged as a controversial African leader. As one of the continent's longest-serving post-colonial heads of state, the Libyan leader enjoys a reputation among many Africans as a maverick statesman. In February 2009, upon being elected chairman of the African Union in Ethiopia, Gaddafi told the assembled African leaders: "I shall continue to insist that our sovereign countries work to achieve the United States of Africa."[69] Gaddafi is also seen by many Africans as a humanitarian, pouring large amounts of money into sub-Saharan states. Large numbers of Africans have come to Libya to take advantage of the availability of jobs there, despite the weak private sector.

His views on African political and military unification have received a relatively lukewarm response from other African governments. On 29 August 2008, Gaddafi held a public ceremony in Benghazi in which he was self-handed the title "King of Kings of Africa" with over 200 African traditional rulers and kings as part of a grassroots effort to encourage African heads of state and government to join with Gaddafi toward a greater political cohesion;[70] this was followed on 1 February 2009 by a coronation ceremony in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia simultaneous with the 53rd African Union Summit, at which he was elected head of the African Union for the year.[71] His January 2009 forum for African kings, however, was cancelled by the Ugandan government (Uganda was to host the forum), since the invitation of traditional rulers to discussion of political affairs contravened Uganda's current constitution, and according to Ugandan foreign ministry spokesperson James Mugume, could have led to instability.[72]

The title of "King of Kings" was reiterated by Gaddafi at the 2009 Arab League Summit, at which he claimed to be the King of Kings, "leader of the Arab leaders" and "imam of the Muslims" in his criticism of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia prior to storming out of the summit.[73]

Notwithstanding his claims of concern for his African roots, Gaddafi has often expressed an overt contempt for the Berbers, a non-Arab people of North Africa, and for their language, maintaining that the very existence of Berbers in North Africa is a myth created by colonialists. He adopted several measures forbidding the use of Berber, and often attacks this language in official speeches, with statements like: "If your mother transmits you this language, she nourishes you with the milk of the colonialist, she feeds you their poison" (1985).[74]

'NATO of the South'

In September 2009, at a South America-Africa summit on Isla Margarita in Venezuela, Colonel Gaddafi joined the host, Hugo Chávez, in calling for an "anti-imperialist" front way across Africa and Latin America. Gaddafi proposed the establishment of a South Atlantic Treaty Organization to rival NATO, saying: "The world’s powers want to continue to hold on to their power. Now we have to fight to build our own power."[75]

Expulsion of Palestinians

In 1995, Gaddafi expelled some 30,000 Palestinians living in Libya, in response to the peace negotiations that had commenced between Israel and the PLO.[76]

UN General Assembly speech

On 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi addressed the 64th session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York, his first visit to the United States, in part because a Libyan diplomat, Ali Treki, has just become president of the General Assembly for 2009–10.[77] Gaddafi spoke for one hour and 36 minutes.[78] A translation of the speech courtesy of Jamahiriya News Agency (JANA) the official Libyan news agency, is available on the internet.[79]

Gaddafi spoke in favor of the preamble to the United Nations Charter, but rejected several provisions of the rest of the Charter; and criticized the United Nations for failing to prevent 65 wars, and invited the General Assembly to investigate the wars that the Security Council had not authorized, and for those responsible to be brought before the International Criminal Court. He also defended the Taliban and Somali Pirates. He also claimed that a foreign military was responsible for the H1N1 outbreak, accused Israel of assassinating John F. Kennedy, and called for a one-state solution for Palestine and Israel, and referred to Barack Obama as "son of Africa".[80]

Following Colonel Gaddafi's speech, in which he criticized the UN Security Council (UNSC) calling it the "Terror Council",[81] Gaddafi failed to attend a special Security Council heads-of-state meeting on 24 September 2009, when a resolution calling for a reduction in the number of nuclear weapons was passed unanimously.[82]

Disappearance of Imam Musa al-Sadr

In August 1978, the Lebanese Shia leader Musa al-Sadr and two companions departed for Libya to meet with government officials. They were never heard from again. At the time, Musa al-Sadr founded Amal Movement, a liberal-Shia Lebanese resistance movement (which later went on to oppose the Israeli invasion of Lebanon). However Amal Movement became powerful much to the annoyance of the PLO which was based primarily in south Lebanon. Libya has consistently denied responsibility, claiming that al-Sadr and his companions left Libya for Italy. Some others have reported that he remains secretly in jail in Libya. Al-Sadr's disappearance continues to be a major dispute between Lebanon and Libya. Lebanese Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri claimed that the Libyan regime, and particularly the Libyan leader, were responsible for the disappearance of Imam Musa Sadr, London-based Asharq Al-Awsat, a Saudi-run pan-Arab daily reported on 27 August 2006.

According to Iranian General Mansour Qadar, the then head of Syrian security, Rifaat al-Assad, told the Iranian ambassador to Syria that Gaddafi was planning to kill al-Sadr. On 27 August 2008, Gaddafi was indicted in Lebanon for al-Sadr's disappearance.[83]

Internal dissent

In October 1993, there was an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Gaddafi by elements of the Libyan army. On 14 July 1996, a football match in Tripoli, organised by his son, was followed by bloody riots as a protest against Gaddafi.

There are a number of political groups opposed to Gaddafi:

- National Conference of the Libyan Opposition

- National Front for the Salvation of Libya

- Committee for Libyan National Action in Europe

A website, actively seeking his overthrow, was set up in 2006 and lists 343 victims of murder and political assassination.[84] The Libyan League for Human Rights (LLHR) – based in Geneva – petitioned Gaddafi to set up an independent inquiry into the February 2006 unrest in Benghazi in which some 30 Libyans and foreigners were killed.

Fathi Eljahmi was a prominent dissident who has been imprisoned since 2002 for calling for increased democratization in Libya.

In February 2011, major political protests (inspired by similar events in the Arab world earlier in the year) broke out in Libya against Gaddafi's government, and are ongoing as of February 21st; Gaddafi has responded to the unrest with violent police and military crackdowns in the cities of Benghazi and Tripoli. Over 200 people are reported to have died in the violence to date.[85]

Public works projects

Great Manmade River

The Great Manmade River is a network of pipes that supplies 6,500,000 m³ of fresh water per day from beneath the Sahara Desert, from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System fossil aquifer, to the cities in the north of Libya, including Tripoli, Benghazi and Sirt.[86] The project consists of more than 1,300 wells, most more than 500 m deep. According to the 2008 edition of Guinness Book of Records, it is the world's largest irrigation project.[citation needed]

The first phase of construction started in 1984, and cost about $5 billion. The completed project may total $25 billion.

Muammar al-Gaddafi has described it as the "Eighth Wonder of the World" and presented the project as a gift to the Third World.[citation needed]

Astronomical observatory

The Libyan National Telescope Project, costing nearly 10 million euros, was ordered by Muammar al-Gaddafi, who has a passionate interest in astronomy. The robotic telescope, which will be two metres in diameter and remote-controlled, will be built by France's REOSC,[87] the optical department of the SAGEM Group.

It will be housed in an air-conditioned building, with a network of four weather stations deployed at a distance of 10 kilometers around it to warn of impending sandstorms that could damage its fragile optics.[88] A desert site at 2200 meters above sea level near Kufra may be chosen as the location for the observatory, which will be North Africa's largest astronomical observatory.

Personal life and family

He is married to Safia Farkash. Gaddafi has eight biological children, seven of them sons. He also had two adopted children. His adopted daughter was killed. His adopted son, Milad Abuztaia Al-Gaddafi is also his nephew. Milad is credited with saving Gaddafi's life during the April 1986 bombing of the Gaddafi compound.[89]

- His eldest son, Muhammad al-Gaddafi, was born to a wife now in disfavour, but runs the Libyan Olympic Committee.

- The next eldest son by his second wife is Saif al-Islam Muammar Al-Gaddafi, who was born in 1972 and is an architect. He runs a charity (GIFCA) which has been involved in negotiating freedom for hostages taken by Islamic militants, especially in the Philippines. In 2006, after sharply criticizing his father's regime, Saif Al-Islam briefly left Libya, reportedly to take on a position in banking outside of the country. He returned to Libya soon after, launching an environment-friendly initiative to teach children how they can help clean up parts of Libya. He is involved in compensation negotiations with Italy and the United States.

- The third eldest, Saadi Gaddafi, is married to the daughter of a military commander. Saadi runs the Libyan Football Federation and signed for various professional teams including Italian Serie A team U.C. Sampdoria, although without appearing in first team games.

- Gaddafi's fourth son, Mutassim Gaddafi, was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Libyan army. He now serves as Libya's National Security Advisor, in which capacity he oversees the nation's National Security Council. His name مُعْتَصِمٌ (بِٱللّٰهِ) /muʿtaṣimu-n (bi l-lāhi)/ can be latinzed as Mutassim, Moatessem or Moatessem-Billah. Saif Al-Islam and Moatessem-Billah are both seen as possible successors to their father.

- The fifth eldest, Hannibal Gaddafi once worked for General National Maritime Transport Company, a company that specializes in Libyan oil exports. He is most notable for being involved in a series of violent incidents throughout Europe. In 2001, Hannibal attacked three Italian policemen with a fire extinguisher; in September 2004, he was briefly detained in Paris after driving a Porsche at 90 mph in the wrong direction and through red lights down the Champs-Élysées while intoxicated; and in 2005, Hannibal in Paris allegedly beat model and then girlfriend Alin Skaf, who later filed an assault suit against him.[90] He was fined and given a four month suspended prison sentence after this incident. In December 2009 police were called to Claridges Hotel in London after staff heard a scream from Hannibal's room. Aline Skaf, now his wife, was found to have suffered facial injuries including a broken nose, but charges were not pressed after she maintained she had sustained the injuries in a fall.[91] On 15 July 2008, Hannibal and his wife were held for two days and charged with assaulting two of their staff in Geneva, Switzerland and then released on bail on 17 July. The government of Libya subsequently put a boycott on Swiss imports, reduced flights between Libya and Switzerland, stopped issuing visas to Swiss citizens, recalled diplomats from Bern, and forced all Swiss companies such as ABB and Nestlé to close offices. General National Maritime Transport Company, which owns a large refinery in Switzerland, also halted oil shipments to Switzerland.[92] Two Swiss businessmen who were in Libya at the time have, ever since, been denied permission to leave the country, and even held hostage for some time.[93] (see Switzerland-Libya conflict). At the 35th G8 summit in July 2009, Gaddafi called Switzerland a "world mafia" and called for the country to be split between France, Germany and Italy.[94]

- Gaddafi's two youngest sons are Saif Al Arab and Khamis, who is a police officer in Libya.

- Gaddafi's only daughter is Ayesha al-Gaddafi, a lawyer who had joined the defense team of executed former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. She married a cousin of her father in 2006.

- His adopted daughter, Hanna, was killed in the April 1986 United States bombing of Libya. At a "concert for peace", held on 15 April 2006 in Tripoli to mark the 20th anniversary of the bombing raid, U.S. singer Lionel Richie told the audience:

- "Hanna will be honoured tonight because of the fact that you've attached peace to her name."[95]

In January 2002, Gaddafi purchased a 7.5% share of Italian football club Juventus for USD 21 million, through Lafico ("Libyan Arab Foreign Investment Company"). This followed a long-standing association with the Italian industrialist Gianni Agnelli and car manufacturer Fiat.[96]

Gaddafi holds an honorary degree from Megatrend University in Belgrade conferred on him by former Yugoslav President Zoran Lilić.[97]

Muammar Gaddafi fears flying over water, prefers staying on the ground floor and almost never travels without his trusted Ukrainian nurse, a “voluptuous blonde,” according to a US document released by WikiLeaks late 2010. Some US embassy contacts have claimed that Gaddafi and the then 38 year-old Galina Kolotnytska have a romantic relationship.[98] Galina's daughter denies this.[99]

Name

Because of the lack of standardization of transliterating written- and regionally-pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been transliterated in many different ways into English and other Latin alphabet languages. Even though the Arabic spelling of a word does not change, the pronunciation may vary in different varieties of Arabic, which may cause a different romanization. In literary Arabic the name معمر القذافي can be pronounced /muˈʕamːaru lqaðˈðaːfi/. [ʕ] represents a voiced pharyngeal fricative (ع). Geminated consonants can be simplified. In Libyan Arabic, /q/ (ق) may be replaced with [ɡ] or [k] (or even [χ]; and /ð/ (ذ) (as "th" in "this") may be replaced with [d] or [t]. Vowel [u] often alternates with [o] in pronunciation. Thus, /muˈʕamːar alqaðˈðaːfiː/ is normally pronounced in Libyan Arabic [muˈʕæmːɑrˤ əlɡædˈdæːfi]. The definite article al- (ال) is often omitted.

An article published in the London Evening Standard in 2004 lists a total of 37 spellings of his name, while a 1986 column by The Straight Dope quotes a list of 32 spellings known at the Library of Congress.[100] This extensive confusion of naming was used as the subject for a segment of Saturday Night Live's Weekend Update in the early 1980s.[citation needed]

"Muammar Gaddafi" is the spelling used by TIME magazine, BBC News, the majority of the British press and by the English service of Al-Jazeera.[101] The Associated Press, CNN, and Fox News use "Moammar Gadhafi". The Edinburgh Middle East Report uses "Mu'ammar Qaddafi" and the U.S. Department of State uses "Mu'ammar Al-Qadhafi". The Xinhua News Agency uses "Muammar Khaddafi" in its English reports.[102]

In 1986, Gaddafi reportedly responded to a Minnesota school's letter in English using the spelling "Moammar El-Gadhafi".[103] The title of the homepage of algathafi.org reads "Welcome to the official site of Muammar Al Gathafi".[104]

Postage stamps

The Libyan Posts (GPTC General Posts and Telecommunications Company) released many postage issues (stamps, souvenir sheets, postal stationery, booklets, etc.) including the subject of Muammar al-Gaddafi. The first issue was a souvenir sheet celebrating the 6th Anniversary of the September Revolution in 1975 (ref. Scott catalogue n.583 – Michel catalogue block 18).[105]

Legacy

Gaddafi Stadium was originally called Lahore Stadium. The facility was renamed to Gaddafi Stadium in 1974 in honour of Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi following a speech he gave at an Organisation of the Islamic Conference meeting in favour of Pakistan's right to pursue nuclear weapons. He is a favorite topic of talk in the weekly satirical podcast "The Bugle". Gaddafi is featured in numerous episodes.

Bodyguards

Gaddafi's choice of bodyguards has been the subject of much media attention. His 40-member bodyguard contingent, known as the Amazonian Guard, is entirely female. All women who qualify for duty supposedly must be virgins, and are hand-picked by Gaddafi himself. They are trained in the use of firearms and martial arts at a special academy before entering service.[106]

Books and other writings

In addition to The Green Book (1975), Gaddafi has authored other works, including:

- Escape to Hell and Other Stories (1998)

- "The One-State Solution", an op-ed piece which appeared in the New York Times in 2009

See also

- Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights

- HIV trial in Libya

- List of national leaders

- List of longest ruling non-royal leaders

References

- ^ a b c Salak, Kira. "National Geographic article about Libya". National Geographic Adventure.

- ^ US Department of State's Background Notes, (November 2005) "Libya – History", United States Department of State. Retrieved on 14 July 2006.

- ^ Charles Féraud, “Annales Tripolitaines”, the Arabic version named “Al Hawliyat Al Libiya”,translated to Arabic by Mohammed Abdel Karim El Wafi, Dar el Ferjani, Tripoli, Libya, vol. 3, p.797.

- ^ Greek newspaper "Ta Nea" (Τα Νέα),21 Feb. 2011ΜΟΥΑΜΑΡ ΚΑΝΤΑΦΙ 42 ΧΡΟΝΙΑ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΞΟΥΣΙΑ

- ^ athens.indymedia.orgΓΙΑΤΙ ΟΙ ΛΥΒΙΟΙ ΘΕΛΟΥΝ ΤΟΝ ΚΑΝΤΑΦΙ

- ^ Lewis, Aidan (28 August 2009). "Profile: Muammar Gaddafi". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Bloodless coup in Libya". London: BBC News. 20 December 2003. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Profile: Muammar Gaddafi, Libyan Leader at time of Lockerbie Bombing by David Blair, Daily Telegraph, 13 August 2009

- ^ Libya cuts ties to mark Italy era.. BBC News. 27 October 2005.

- ^ "The Green Book, Third Volume "The Social Basis of the Third World Theory", The Social Basis of the Third World Theory". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Third Volume "The Social Basis of the Third World Theory", The Nation". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Second Volume "The Solution of the Economic Problem", Need". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Second Volume "The Solution of the Economic Problem", Housing". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Second Volume "The Solution of the Economic Problem", Income". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, First Volume "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy", Popular Conferences and People's Commitees. «Popular Conferences are the only means to achieve popular democracy»". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Second Volume "The Solution of the Economic Problem", Domestic Servants". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, Third Volume "The Social Basis of the Third World Theory", Education". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, First Volume "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy", The Law of Society". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Constitutional Declaration of Libya, Article 2. «The Holy Qur'an is the social code in the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, since authority belongs solely to the people, by whom it is exercised through people's congresses, people's committees, trade unions, federations and professional associations (the General People's Congress, the working procedures of which are established by law).»

- ^ "The Green Book, First Volume "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy", The Instruments of Governing". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, First Volume "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy", Popular Conferences and People's Committees". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The Green Book, First Volume "The Solution of the Problem of Democracy", Who Supervises the Conduct of Society?". Mathaba.net. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Facts on File 1980 Yearbook p353, 451

- ^ "judgment of the ICJ of 13 February 1994" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ Robert Andrew Stein (US Chargé d'Affaires ad interim to Libya) to Department of State, May 16, 1974

- ^ Victor John Krehbiel (US Ambassador to Finland) to Department of State, March 4, 1974

- ^ Robert Carle (US Embassy in Tripoli) to Department of State, September 2, 1976

- ^ President Ronald Reagan (10 March 1982). "Proclamation 4907 – Imports of Petroleum". United States Office of the Federal Register.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (28 August 2010). "Yvonne Fletcher killer may be brought to justice". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "Analysis: Lockerbie's long road". London: BBC News. 31 January 2001. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (1 September 2009). "Britain's past relations with Libya: Yvonne Fletcher and plot to kill Gaddafi". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ "Libya completes Lockerbie payout". London: BBC News. 22 August 2003. Retrieved 5 March 2005.

- ^ "Libya compensates terror victims". London: BBC News. 31 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Severin Carrell, Scotland correspondent (29 June 2007). "Libyan jailed over Lockerbie wins right to appeal". Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "BBC — Anger at Lockerbie bomber welcome". London: BBC News. 21 August 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "CNN – Obama condemns Lockerbie bomber's 'hero's welcome'". CNN. 21 August 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Brown finally condemns Megrahi welcome". Sbs.com.au. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "When in Rome, Gaddafi will do as the Bedouins". Sydney Morning Herald. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Ed Pilkington in New York (25 August 2009). "New Jersey town outraged over upcoming Gaddafi visit". Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Battle, Pat (28 August 2009). "Gadhafi Cast Out of Garden (State): Source". Nbcnewyork.com. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Qaddafi Cancels Plans to Stay in New Jersey

- ^ Gadaffi's tent finds home on Donald Trump's estate M&G

- ^ "Gadhafi: UN Security Council is undemocratic". Finalcall.com. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Anger and support for Gadhafi". CNN. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Indyk, Martin S. (2004). "The Iraq War did not Force Gaddafi's Hand". The Financial Times. Retrieved 5 March 2006.

- ^ Leverett, Flynt. "Why Libya Gave Up on the Bomb". New York Times year=2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2006. Retrieved 5 March 2006.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Thomson, Mike. "The Libyan Prime Minister". Today Programme. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ^ "World | Africa | US to renew full ties with Libya". London: BBC News. 15 May 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Libya's Gaddafi Urges Backers to 'Kill' Enemies". The Epoch Times. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ "Sarkozy signs deals with Gaddafi". London: BBC News. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Libya: Ministries Abolished". Carnegieendowment.org. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Visit of Condoleezza Rice, BBC News 5 September 2008". London: BBC News. 5 September 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "The One-State Solution", New York Times 22 January 2009

- ^ a b "Ratifica ed esecuzione del Trattato di amicizia, partenariato e cooperazione tra la Repubblica italiana e la Grande Giamahiria araba libica popolare socialista, fatto a Bengasi il 30 agosto 2008" (in Italian). Parliament of Italy. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Gaddafi to Rome for historic visit". ANSA. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Berlusconi in Benghazi, Unwelcome by Son of Omar Al-Mukhtar". The Tripoli Post. 30 August 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Italia-Libia, firmato l'accordo". La Repubblica. Italy. 30 August 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Libya agrees pact with Italy to boost investment". Alarab Online. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Gheddafi a Roma, tra le polemiche". Democratic Party. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Gheddafi protetto dalle Amazzoni". La Stampa. Italy.

- ^ "Gheddafi a Roma: Radicali in piazza per protestare contro il dittatore" (in Italian). Iris Press. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ The Earthtimes (10 July 2009). "The Earth Times Online Newspaper". Earthtimes.org. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Gaddafi comes in from the cold". Express.co.uk. 11 July 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Gaddafi meets Obama in Aquila". Afriquejet.com. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Feeing the hungry to changing the climate – what the G8 did for us". Euronews.net. 28 June 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ G8:Stretta Di Mano Obama – Gheddafi, Berlusconi Li Avvicina[dead link]

- ^ "Storica stretta di mano fra Obama e Gheddafi". Unionesarda.ilsole24ore.com. 20 November 1948. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Europe should convert to Islam: Gaddafi". The Times of India. India. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Gaddafi vows to push Africa unity". London: BBC News. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ "Gaddafi: Africa's king of kings". London: BBC News. 29 August 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Libyan leader imposes himself as 'King of Kings' in Africa". Religiousintelligence.co.uk. 3 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Uganda bars Gaddafi kings' forum". London: BBC News. 13 January 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Gaddafi Storms Out of Arab Summit, Slams Saudi King for Pro-Americanism". HuffingtonPost.com. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ^ See Rapport général sur la situation des droits humains des Imazighen de Libye – 2007, p. 5. Inside the document, more details about Gaddafi's attitude towards Berbers and Berber.

- ^ Hannah Strange (28 September 2009). "Gaddafi proposes 'Nato of the South' at South America-Africa summit". The Times. London. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ Tech.mit.edu

- ^ "The Nation: All Eyes On Obama At The United Nations". Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "General Debate of the 64th Session (2009) – Statement Summary and UN Webcast". Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Gadafi's speech to the UN General Assembly(2009)". Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ "Libyan Leader Delivers a Scolding in U.N. Debut". New York Times author=Neil MacFarqhuar. 23 september 2009. Retrieved 19 january 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ James Bone & Francis Elliott (24 September 2009). "Colonel Gaddafi chastises 'terror council' in rambling, 94-minute speech". The Times. London. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "UN Security Council Adopts Measure on Nuclear Arms". New York Times author=Helene Cooper & Sharon Otterman. 24 September 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ "Gaddafi charged for cleric kidnap". London: BBC News. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Stop Gaddafi". Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Watkins, John (18 March 2006). "Libya's thirst for 'fossil water'". London: BBC News. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Sagem. "SAGEM". Sagem-ds.com. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "卡扎菲千万美元定购望远镜 可能安装在沙漠深处(组图)". 东方军事. 6 January 2005. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ "Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi v. [[The Daily Telegraph]]". 21 August 2002. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Bremner, Charles (4 February 2005). "Hannibal gives Gaddafi a bad name". The Times. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Police called to Gaddafi son's hotel room after staff hear screams – Crime, UK". The Independent. London. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Libya 'halts Swiss oil shipments'". London: BBC News. 24 July 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Merz hints at new Gaddafi meeting". 18 September 2009.

- ^ Bachmann, Helena. "Libyan Leader Gaddafi's Oddest Idea: Abolish Switzerland". TIME date=25 September 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ "Libya concert marks US bomb raids". London: BBC News. 15 April 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ^ "Muammar Gaddafi: the wise investor". Business Today. 7 November 2001. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ "Impostor Defends Bulgarian Nurses before Gaddafi". Standart News Template:Ru icon. 3 March 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ "Gaddafi never travels without his 'voluptuous blonde' nurse". Yahoo India! News. 29 November 2010

- ^ Segognya, Nov. 30th 2010

- ^ "How are you supposed to spell Muammar Gaddafi/Khadafy/Qadhafi?". The Straight Dope. 1986. Retrieved 5 March 2006.

- ^ "Gaddafi in Moscow for arms talks". Al-Jazeera English. 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Xinhuanet.com". News.xinhuanet.com. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Second-Graders Get Letter From Khadafy." The Associated Press 16 May 1986: Domestic News.

- ^ "Gaddafi's personal website". Algathafi.org. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ "Libyan Stamps online". Libyan-stamps.com. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Qaddafi's Angels Guard the Libyan During Deal with France

External links

- Official personal website

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Template:Worldcat id

- Collected material at Answers.com

- Articles

- The NS Profile: Muammar al-Gaddafi, Sholto Byrnes, New Statesman, 27 August 2009

- Libya's Last Bedouin, Rudolph Chimelli, Qantara.de, 2 September 2009

- Gaddafi: The Last Supervillain?, slideshow by Life magazine

- Gaddafi's 40th Anniversary, slideshow by The First Post

- Current events from February 2011

- Use dmy dates from December 2010

- Muammar al-Gaddafi

- 1942 births

- Arab nationalist heads of state

- Chadian–Libyan conflict

- Cold War leaders

- Conspiracy theorists

- Current national leaders

- Heads of state of Libya

- Leaders who took power by coup

- Libyan revolutionaries

- Libyan Sunni Muslims

- Living people

- International opponents of apartheid in South Africa

- Attempted assassination survivors

- Pan-Africanism

- People from Sirt

- Members of the General People's Committee of Libya

- Libyan military personnel

- Prime Ministers of Libya

- People of the 2011 Libyan protests